Abstract

Enhanced angiogenesis is a hallmark of cancer. Pleiotrophin (PTN) is an angiogenic factor that is produced by many different human cancers and stimulates tumor blood vessel formation when it is expressed in malignant cancer cells. Recent studies show that monocytes may give rise to vascular endothelium. In these studies, we show that PTN combined with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) induces expression of vascular endothelial cell (VEC) genes and proteins in human monocyte cell lines and monocytes from human peripheral blood (PB). Monocytes induce VEC gene expression and develop tube-like structures when they are exposed to serum or cultured with bone marrow (BM) from patients with multiple myeloma (MM) that express PTN, effects specifically blocked with antiPTN antibodies. When coinjected with human MM cells into severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice, green fluorescent protein (GFP)–marked human monocytes were found incorporated into tumor blood vessels and expressed human VEC protein markers and genes that were blocked by anti-PTN antibody. Our results suggest that vasculogenesis in human MM may develop from tumoral production of PTN, which orchestrates the transdifferentiation of monocytes into VECs.

Introduction

Angiogenesis is essential to the growth and metastasis of malignant tumors.1 Angiogenic factors recruit vascular endothelial cells (VECs) from preexisting endothelial cells (angiogenesis) or circulating endothelial progenitor cells (vasculogenesis).2,3 Hematopoietic cells participate in the development of blood vessels and endothelial cells4 and their progenitors have been identified in the peripheral blood (PB) of cancer patients including multiple myeloma (MM).1,3,5 The levels of these circulating progenitors have been directly correlated with disease severity in MM.5 These progenitor cells play important roles in inducing the angiogenic switch that is critical to the development of the blood supply that is required for metastatic growth of tumors.6 PB mononuclear cells (MCs) have been shown to contribute to vasculogenesis.7,8 It has been reported that myeloid progenitor cells, dendritic cells, and MCs may produce vascular endothelium.7–9 Monocytes and macrophages may give rise to VECs,7 accumulate around tumors, and stimulate blood vessel formation. Furthermore, depletion of these cells reduces tumor growth.10 Specific patterns of gene expression occur in macrophages that infiltrate tumors and support their growth.11 These studies suggest the importance of cells in the monocyte/macrophage lineage in blood vessel formation and tumorigenesis

PTN, an 18-kDa heparin-binding protein, is an important developmental and angiogenic factor12,13 that is highly expressed during embryogenesis but shows very limited expression in adult tissues.14,15 Its expression is restricted to neurons, glia, and limited mesenchymal tissues in postnatal life.14,15 PTN is up-regulated at sites of wound healing and blood vessel formation,12 and stimulates creation of vessels when injected into injured tissues.13 Many different solid tumors express this protein,16–19 and its secretion from tumor cells stimulates new blood vessel formation.17,20 We have recently demonstrated that PTN is expressed and secreted by the malignant plasma cells from MM patients.21,22 Serum levels of PTN are elevated in cancer patients including MM, and the amount of this protein correlates with the patient's disease status and response to treatment.22–24 Anti-PTN antibody treatment reduces growth and enhances apoptosis of MM cell lines and fresh tumor cells from MM patients in vitro.21 Importantly, this antibody also suppresses the growth of MM in vivo using a severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)–hu murine model.21 Other studies using both ribozyme and RNA interference-based approaches have shown that inhibiting PTN reduces the growth of solid tumors in vivo.25,26

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a cytokine that plays a key role in the development of normal and tumor blood vessels, including in MM,27–29 and we have demonstrated that an antibody with both human and mouse anti-VEGF activity markedly reduces the growth of human MM tumors growing in SCID mice.30

Macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) regulates the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of monocytes,31 and is responsible for the migration of monocytes/macrophages to tumors and their activation.32 Up-regulation of M-CSF in injured tissues provides tissue repair through these effects on cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage as well as through increasing cells with an endothelial cell phenotype.33 Although M-CSF also promotes tumor angiogenesis,34 the mechanism by which M-CSF stimulates tumor angiogenesis has not been previously determined.

Recent reports suggest that transdifferentiation, defined as a change of a cell or tissue from one differentiated state to another, may occur in some cell types including monocytes.35–37 Herein, we report a novel mechanism of early tumor blood vessel formation involving the secretion of the specific angiogenic proteins PTN and M-CSF from malignant plasma cells that stimulates monocytes to become transdifferentiated into endothelial cells that incorporate into tumor blood vessels. Although PTN may become activated at areas of nerve injury and be required for repair of nervous system damage,38 the expression of this protein is very limited in healthy adult tissues. Thus, blocking PTN may provide a way to prevent early blood vessel formation within tumors with minimal impact on normal cellular functions.

Methods

Cells, cell culture, and collection of blood and BM samples

The human RPMI8226 and U266 MM cell lines and monocyte (THP-1) and myelomonocytic (U937) cell lines were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Normal human BM was purchased from Allcells (Berkeley, CA). Highly purified human T cells from healthy donors (Immunomod, Seattle, WA) were obtained using Dynabeads (Dynal Biotech, Carlsbad, CA) with pan–T-cell antibodies as previously described.39 All cells were cultured in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, nonessential amino acids, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 25 mM HEPES, 200 units/mL penicillin, and streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. PB and BM aspirates were collected from MM patients and PB from healthy control subjects after obtaining Institutional Review Board approval (Western IRB BIO 001) and informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Serum was isolated by centrifugation and stored at −80°C. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMCs) were isolated by density-gradient centrifugation using Histopaque-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). CD14+ monocytes were purified by magnetic bead selection (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Briefly, 108 PBMCs were incubated with 200 μL anti-CD14 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) in ice for 30 minutes. The cells were washed with cold 1× PBS with 2% FCS and centrifuged at 300g for 10 minutes and then resuspended in 1× PBS with 2% FCS. The cell suspension was applied to the magnetic column and unbinding cells were passed through by washing 3 times with 1× PBS with 2% FCS.

Coculture and tube-like structure formation assay

Purified monocytes were cultured in 6-well plates coated with collagen I (Becton Dickinson, Gaithersburg, MD). After 1 hour of culture, M-CSF (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was added to the cells. PTN (50 nM; R&D Systems) and/or VEGF (10 ng/mL; R&D Systems) were added to the cells following 24 hours and 5 days of culture. The cells were cultured for a total of 7 days. Human BM from MM patients with more than 90% plasma cells or U266, RPMI8226, or U937 cells were cocultured with CD14+ monocytes using Transwell culture plates coated with collagen I for 14 days. In some experiments, CD14+ cells were exposed to anti-PTN antibodies (final concentration: 1 μg/mL; R&D Systems).

Tube-like structure formation was assessed after the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with anti–Flk-1 antibodies (2 μg/mL; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent analysis of VEC markers

Five-micrometer sections were cut after fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde (for cultured cells) or 10% formalin (for tissue). The slides were blocked with 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) and 3% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature (RT). The samples were exposed to the following antibodies: anti–Tie-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–Flk-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-CD144 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), anti–von Willebrand factor (VWF; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-PTN (R&D Systems), and anti–M-CSF antibodies (R&D Systems). Slides were washed 3 times with TBST and treated with ARH conjugated with either anti–mouse, anti–rabbit, or anti–goat antibodies (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) diluted 1:500 in TBST at RT for 2 hours. The slides were washed 3 times in TBST and placed in 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) buffer for 5 minutes, and color was detected using an AEC kit (Vector, Burlingame, CA). For immunofluorescent analysis (IFA), the slides were blocked with 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) and 3% BSA for 1 hour at RT and were incubated with anti–mouse IgG conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE) (1:100; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) at 4°C overnight. The slides were washed 3 times with PBS for 15 minutes at RT and incubated with FITC-conjugated swine anti–goat or anti–mouse antibody (Biosource, Camarillo, CA) for 2 hours at RT. Anti-DAPI antibody was added to slides as a nuclear marker. The slides were washed as before and mounted with aqueous mounting media (Biomeda, Foster City, CA). Endothelial markers were identified under the microscope (Olympus BX51; Olympus, San Diego, CA) and merged cells were analyzed by Microsuite Biological Suite program (Olympus BX51) or scanned using a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY).

Flow cytometric analysis

Purified human CD14-expressing cells were treated with PTN plus M-CSF plus VEGF. Following 7 days of culture, the cells were fixed using 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes in ice and washed with PBS twice. The cells were resuspended in 100 μL diluted mouse antihuman CD45 and CD133 (BD Biosciences) for 30 minutes in ice and washed with PBS for flow cytometric analysis using a Beckman Coulter FC500 cytometer with Cytomics CXP software (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Statistical analysis of flow cytometric results was completed on the proportion of cells expressing CD45 using the Microsoft Office Excel t test (Redmond, WA) on cells treated with PTN, M-CSF, or the combination of both cytokines.

Western blot analysis

Forty micrograms protein lysates from monocytes were electrophoresed on a 4% to 15% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, 100 V for 3 hours at 4°C, and then proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) overnight at 50 mA, 4°C. The membranes were incubated with 5% BSA in TBST for 1 hour at RT. Anti–Tie-2, anti–Flk-1, anti-VWF, or anti–β-actin antibodies were added and incubated overnight at 4°C. Protein expression was visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) and quantified using a Vesa-Doc gel documentation system (Bio-Rad).

In vivo studies

Human LAGλ-1 MM tumors were implanted intramuscularly in 6- to 8-week-old homozygous male C.B-17 SCID/SCID mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Madison, WI) as previously described.40 The LAGλ-1 tumor was established from serial intramuscular passages of BM derived from an IgG-producing MM patient and has been maintained for more than 5 years.40 Animal studies were conducted according to protocols approved by the Animal Research Committee at the Institute for Myeloma & Bone Cancer Research. We injected subcutaneously 106 LAGλ-1 cells, 106 THP-1 monocytes, or coinjected both cell types into SCID mice. In some experiments, mice coinjected with 106 LAGλ-1 and 106 THP-1 cells were also treated twice weekly with intraperitoneal injections of 10 mg/kg of either polyclonal goat anti–human PTN or control preimmune goat IgG antibodies. THP-1 cells that had been marked with green fluorescent protein (THP-1/GFP) were used in some of the experiments. THP-1 cells were marked with GFP as previously described.21 Mice were killed 6 weeks after injection. Tumors were paraffin- or frozen-sectioned and analyzed for tumor blood vessels that contained THP-1/GFP monocytes as indicated by the presence of autofluorescent red blood cells in the lumen of tumor blood vessels. Total RNA was also isolated from tumor tissue for reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of VEC gene expression in mice injected with LAGλ-1 or THP-1 alone or coinjected with both cell types.

PCR and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from monocytes treated with cytokine combinations that were serially diluted with T cells (Immunomod) to determine the proportion of cells expressing each gene. All cell numbers were adjusted to 106 cells by adding highly purified T cells that lacked both VEC and monocyte gene expression. Total RNA was also isolated from monocytes or THP-1 cells exposed to BM from MM or healthy subjects or PCL serum and also from U937, LAGλ-1, U266, and RPMI8226 cells as well as xenografts derived from mice injected with LAGλ-1 coinjected with THP-1 cells or LAGλ-1 or THP-1 cells alone (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA was resuspended in 0.1% diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water, digested with DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) to remove contaminating DNA, and extracted with phenol/chloroform followed by ethanol precipitation. Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA and amplified using the ThermoScript RT-PCR System (Invitrogen). PCR was performed again using the ThermoScript RT-PCR System (Invitrogen) and a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for 1 cycle at 94°C 2 minutes, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 58°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 1 minute, and 1 cycle at 72°C for 5 minutes. The following primers were used: c-fms, (L) agaacatccacctcgagaaga, (R) gaagtggagacaggcctcat; Flk-1, (L) caaccagacggacagtggta, (R) acagactccctgcttttgct; Tie-2, (L) gcaacttgacttcggtgcta, (R) cacagccgaggagtgtgtaa; VWF, (L) ctccaggatggctgtgatact, (R) caggtgcctggaattttcat; VE-cadherin (CD144), (L) atcgaggtgaagaaggacga, (R) gtccccagtcgttaaggaagt; PTN, (L) tgccagaagactgtcaccat, (R) ctcctgtttcttgccttcctt; CD133, (L) tggccaccgctctagatact (R) tcctatgccaaaccaaaaca; CD45, (L) cgtaatggaagtgctgcaatgt, (R) ctgggaggcctacacttgaca; and GAPDH, (L) actgccacccagaagactgt, (R) ccagtagaggcagggatgat.

Single cells lining tumor blood vessels were microdissected41,42 from tumors derived from mice injected with LAGλ-1 cells alone or LAGλ-1 coinjected with THP-1/GFP cells and total DNA was purified from cells and PCR was performed for 40 cycles. Primers to identify human alu DNA were (L) tggctcacgcctgtaatcc and (R) ttttttgagacggagtctcg, and those to identify mouse pf1 DNA were (L) ccgggcagtggtggcgcatg and (R) gtttggtttttgagcagggt.43–45

ELISA for PTN secretion

Fresh MM and control BMMCs and the RPMI8226, U266, THP-1, and U937 cell lines were cultured in RPMI1640-containing supplements (described in “Cells, cell culture, and collection of blood and BM samples”) and 5% FBS. Supernatants were obtained from the culture medium after 48 hours for determination of PTN concentrations as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously22 and performed in triplicate.

Laser-capture single-cell microdissection of tumor tissue

Microdissection of single endothelial cells was performed by PixCell IIe Laser Capture Microdissection System (Arcturus, Mountain View, CA).41,42 Tumors were paraffin sectioned and H&E stained. The slide was moved manually into an area where a blood vessel was present, and then was held by a vacuum chuck. After sliding the CapSure cassettes (Arcturus, Mountain View, CA) onto their modules, the devices were placed on the sample. A single lining cell from a tumor blood vessel was locked by a laser pin and then the laser was switched on. The cell was cut with the laser and attached to CapSure. The dissected cell was lysed with lysis buffer (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) to prepare it for PCR with human alu or mouse pf1 primers.43–45

Results

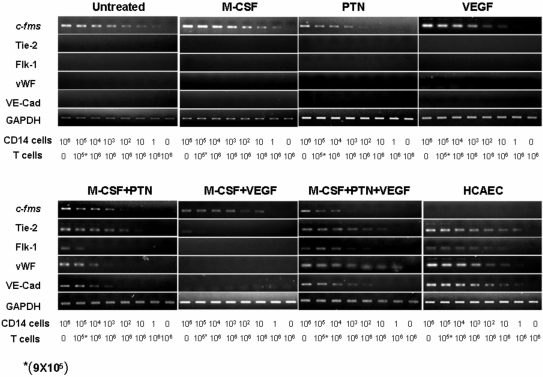

PTN in combination with M-CSF induces VEC gene expression in CD14+ cells that is enhanced by VEGF

CD14+ PBMCs were isolated from healthy human donors by Ficoll density-gradient centrifugation, followed by magnetic bead selection (Miltenyi Biotec). Following this selection, more than 95% of the cells expressed the CD14 marker as determined by flow cytometric analysis (data not shown). These CD14+ cells (106 cells) did not express the VEC genes Tie-2, Flk-1, von Willebrand factor (VWF), and VE-cadherin (CD144) with primers capable of detecting their expression with a sensitivity of 1 human coronary arterial endothelial cell (HCAEC) in 106 T cells (untreated and HCAEC lanes in the gels shown in Figure 1). Although approximately 3% of circulating mononuclear cells isolated through flow cytometric sorting have been shown to express Tie-2,46 Miltenyi beads irreversibly bind cells that express VEC markers including Tie-2. Thus, monocytes that show Tie-2 expression are not present in cells obtained following Miltenyi bead selection procedures as we also have shown. Next, we determined whether PTN could induce fresh CD14+ cells to express VEC genes and reduce monocyte gene expression. Although monocytes cultured with PTN or M-CSF alone did not show expression of VEC genes or change the proportion of cells expressing the monocyte gene c-fms, the combination of these cytokines induced the expression of VEC genes and reduced the proportion of cells expressing c-fms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PTN and M-CSF together induce VEC gene expression in fresh monocytes in vitro. Human CD14+ monocytes were purified from PB by density gradient centrifugation and anti-CD14 antibody treatment with magnetic bead selection. After 1 hour of culture, M-CSF (10 ng/mL) was added, and/or PTN (50 nM) and/or VEGF (20 ng/mL) were added twice to the cultures (after 24 hours and 5 days of culture). Cells were cultured for a total of 7 days. Total RNA was isolated from 106 cells containing monocytes treated with various cytokine combinations that were serially diluted with T cells. RT-PCR was performed with primers capable of detecting VEC gene expression (Tie-2, Flk-1, VWF, and VE-Cad [cadherin]) with a sensitivity of 1 human coronary arterial endothelial cell (HCAEC) in 106 T cells that lacked VEC gene expression to show that there was no VEC contamination within the purified fresh monocyte population. GAPDH was used as a control. Using primers for the monocyte-specific gene c-fms, monocytes were detected with a sensitivity of 1 cell diluted in 106 T cells.

VEGF, another angiogenic factor that is produced by MM cells,29 as well as the fresh MM BM and MM cell lines evaluated in this study (data not shown), did not induce VEC gene expression in fresh monocytes when used alone or in combination with PTN (Figure 1 and data not shown). None of these genes was expressed when the cells were treated with the combination of VEGF and M-CSF except Tie-2, and expression of this gene was detectable in only 106 undiluted monocytes but not in monocytes that were further diluted in T cells (Figure 1). However, when PTN, M-CSF, and VEGF were added together to CD14+ cells, the proportion of cells expressing VEC genes markedly increased compared with cells exposed to the combination of PTN with M-CSF, and the frequency of c-fms–expressing cells was further decreased (Figure 1).

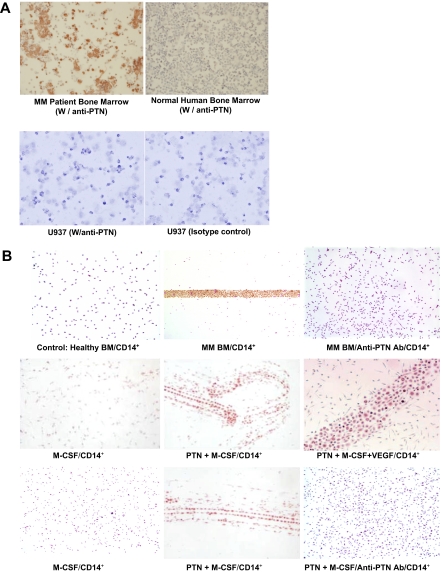

CD14+ cells exposed to MM tumor cells express VEC genes and form tube-like structures that are blocked by anti-PTN antibody

BM from MM patients showed expression of PTN unlike normal BM (Figure 2A). Using Transwell plates, fresh monocytes cultured with MM but not healthy donor BM formed tube-like structures that stained with anti–Flk-1 antibody that was blocked with anti-PTN antibody (Figure 2B top row). U937 cells did not express PTN (Figure 2A), and using Transwell plates these cells did not induce tube formation or Flk-1 expression in fresh CD14-expressing monocytes (data not shown). M-CSF alone did not induce tube formation or Flk-1 staining (Figure 2B middle and bottom rows, left) and neither did PTN or VEGF alone (data not shown). In contrast, the combination of PTN with M-CSF induced monocytes to form Flk-1+ tubes (Figure 2B middle and bottom rows, middle) which was blocked with anti-PTN antibody (Figure 2B bottom row, right). The tubes were more highly organized and their morphology more closely resembled endothelial cells when VEGF was added to cells cultured with PTN and M-CSF (Figure 2B middle row, right).

Figure 2.

MM tumor cells stimulate tube-like structure formation and Flk-1 staining in freshly obtained CD14+ cells that are blocked by anti-PTN antibodies; PTN and M-CSF induce tube-like structure formation and Flk-1 staining in fresh human monocytes in vitro that is blocked by anti-PTN antibodies. (A) BMMCs from a MM patient containing more than 90% plasma cells and a healthy control subject and U937 cells were stained with either anti-PTN or isotype-matched control antibodies (40×/objective lens, Olympus BX51; Olympus, San Diego, CA). (B top row) CD14+ cells were cocultured with BMMCs from a healthy donor or MM patient containing more than 90% tumor cells with and without anti-PTN antibody using Transwell culture plates for 14 days. Light microscopy of CD14+ cells stained with an anti–Flk-1 antibody is shown. (Middle row) CD14+ cells were exposed to M-CSF alone, PTN and M-CSF together, or the combination of PTN, M-CSF, and VEGF. The cells were stained with anti–Flk-1 antibody using immunohistochemical (IHC). (Bottom row) In a separate experiment, CD14+ cells were exposed to M-CSF alone or the combination of M-CSF and PTN with or without anti-PTN antibody.

Fresh MM BM induced protein expression of Flk-1, Tie-2, and VWF in monocytes as determined with Western blot analyses, and incubation with anti-PTN antibody markedly reduced expression of these VEC proteins (Figure 3A). The PTN-producing and -secreting MM cell line U26621 (Figure 3B-D) and serum containing high PTN levels22 from a plasma cell leukemia (PCL) patient induced VEC (VWF, Tie-2, and Flk-1) gene expression in monocytes (Figure 3E); VEC gene expression was blocked by anti-PTN antibody but not by nonspecific antibody (Figure 3E,F). VEC expression was not detected in monocytes alone or exposed to M-CSF or healthy donor serum or BM (Figure 3E,F).

Figure 3.

MM cells as well as PCL serum induce VEC gene and protein expression in monocytes that is blocked by anti-PTN antibodies. (A) Freshly obtained CD14+ cells cocultured with MM BM tumor cells with and without anti-PTN antibody were analyzed for Flk-1, Tie-2, and VWF protein expression using Western blot analysis. Haceks served as a positive control. (B) U937, U266, and RPMI8226 cells were analyzed for PTN and GAPDH gene expression with RT-PCR. (C) LAGλ-1 and U266 cells were stained with either anti-PTN or isotype-matched control antibodies. (D) THP-1, U937, RPMI8226, and U266 cells were cultured for 48 hours and the culture supernatant was analyzed for PTN protein concentration by ELISA. Data for PTN graphed are the average of experiments performed in triplicate and show means plus or minus SEM. (E) Endothelial cells (HCAECs) or CD14+ cells alone or exposed to M-CSF, the PTN-producing MM cell lines U266 and RPMI8226, or serum from a healthy control subject or a patient with PCL containing high levels of PTN (3.4 ng/mL)22 were analyzed for gene expression using primers specific for VWF, Tie-2, Flk-1, and GAPDH with RT-PCR. (F) Endothelial cells (HCAECs) or CD14+ cells alone or exposed to M-CSF, the PTN-producing MM cell line U266, or BM from a healthy control subject or serum from the patient with PCL were analyzed for expression of the VWF, Tie-2, and Flk-1 genes in the presence of anti-PTN or isotype-matched control antibodies.

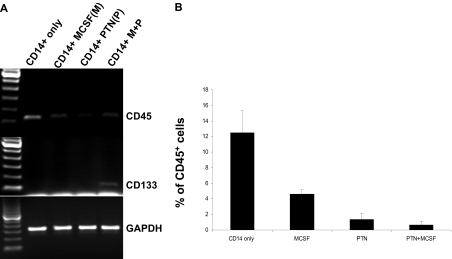

Gene expression of the leukocyte marker CD45 and endothelial cell precursor antigen CD133 was determined in purified CD14+ cells following treatment with PTN, M-CSF, or both proteins. CD133 gene expression was not detected in CD14 cells treated with M-CSF or PTN alone but it was expressed when the cells were treated with the combination of both cytokines (Figure 4A). CD45 gene expression was reduced following exposure to M-CSF, PTN, or the combination of both cytokines (Figure 4A). Consistent with these results, the proportion of CD14+ cells expressing CD45, as determined using flow cytometric analysis, decreased in the presence of these cytokines compared with no treatment (vs M-CSF [P = .036]; vs PTN- [P = .002]), with the most marked reduction observed in cells exposed to PTN and M-CSF together (P = .001; Figure 4B). Using flow cytometry, we demonstrated that CD133 was expressed in only a small percentage of CD14-expressing cells (< 1%) so that determination of differences between cells treated with different cytokines was not possible (data not shown).

Figure 4.

CD133 and CD45 expression in CD14+ cells alone or treated with PTN, M-CSF, or the combination of both cytokines for 7 days. (A) RT-PCR analysis of CD133 and CD45 gene expression in CD14+ cells alone or treated with PTN, M-CSF, or the combination of these cytokines. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of CD45 expression on CD14+ cells following treatment with no treatment, PTN, M-CSF, or the combination of both cytokines. The proportion of cells expressing CD45 is shown. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and error bars represent multiple assays.

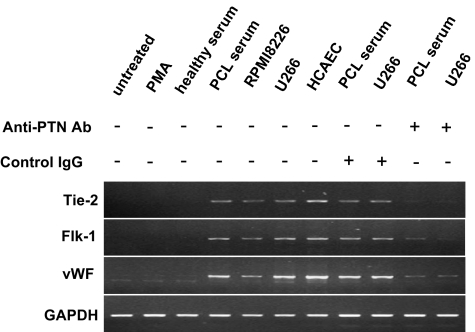

The monocyte cell line THP-1 expresses VEC genes following exposure to MM cells or serum that is inhibited by anti-PTN antibody

PTN is not expressed by the human monocyte cell line THP-1 or following treatment with M-CSF or TNFα (data not shown). When THP-1 cells were cultured alone, with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), a compound that stimulates monocytes to become macrophages, or healthy donor serum, VEC gene expression was not detected (Figure 5). However, when THP-1 cells were cocultured in Transwell plates with cells from the serum of a PCL patient with high serum PTN levels or the PTN-expressing cell lines RPMI822621 or U266 VEC gene expression was induced in THP-1 cells, and the addition of anti-PTN antibody markedly reduced this, whereas control antibody had no effect (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

To determine whether PTN induced the monocyte cell line THP-1 to express VEC genes, total RNA was isolated and separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis after THP-1 monocytes were cultured with PMA, PCL serum, or normal human serum or cocultured with U266 and RPMI8226. In addition, THP-1 cells exposed to U266 or PCL serum were also treated with either anti-PTN or isotype-matched control antibodies during tissue culture. RT-PCR was performed on RNA from THP-1 cells with primers specific for the Tie-2, Flk-1, VWF, and GAPDH genes. HCAECs were used as a positive control.

Following coinjection with MM cells, THP-1 cells express VEC genes and become incorporated into tumor blood vessels in vivo

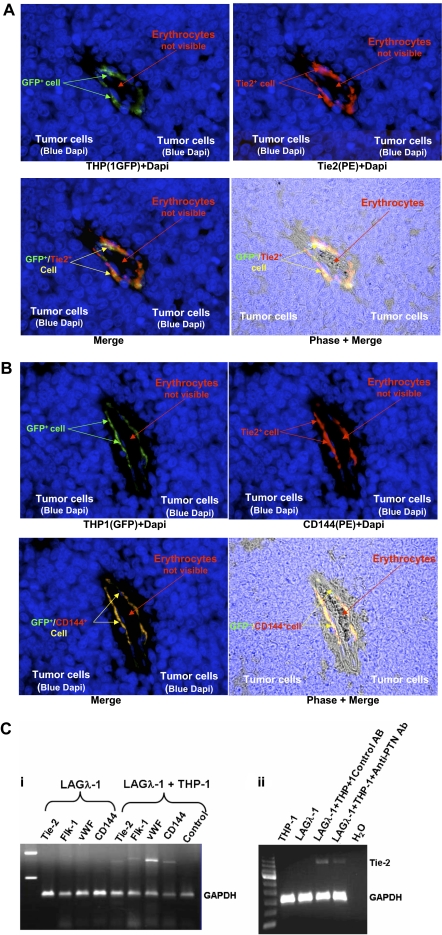

THP-1 cells that express GFP (THP-1/GFP) were mixed with human MM LAGλ-140 cells that express PTN21 and were injected into C.B-17 SCID mice. The animals were killed at 6 weeks and the tumors were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy and scanned using confocal microscopy. GFP+ cells colocalized with cells stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti–human Tie-2 or CD144 antibodies in the tumor blood vessels (Figure 6A,B). Antibodies directed against human Tie-2 or CD144 failed to react with mouse VECs (data not shown). Xenografts from mice injected with LAGλ-1 alone lacked human VEC gene expression, whereas xpression of VEC markers was detected in tumors from animals injected with LAGλ-1 and THP-1 cells together (Figure 6Ci) and Tie-2 gene expression was markedly reduced when these mice were treated with anti-PTN antibody but not when treated with isotype-matched control antibody (Figure 6Cii). Thus, PTN secreted from human MM induced VEC marker expression in monocytes and these cells became incorporated into tumor blood vessels.

Figure 6.

GFP-marked THP-1 cells (THP-1/GFP) coinjected with human LAGλ-1 MM tumor cells into C.B-17 SCID/SCID mice become incorporated into tumor blood vessels and express VEC markers. Human LAGλ-1 MM tumor cells were injected subcutaneously alone or in combination with THP-1/GFP monocytes into mice. Six weeks later, tumors were excised and immediately fixed with formalin. Tumor sections were prepared using standard histologic protocols. (A) Cells expressing GFP were determined using fluorescence and immunofluorescence was determined in sections stained with anti–human Tie-2 and anti-Dapi antibodies. (B) Another tumor blood vessel from a SCID mouse containing LAGλ-1 and THP-1/GFP cells was stained with anti–human CD144 (VE-cadherin) antibodies. Similarly, cells expressing GFP were determined using fluorescence and immunofluorescence was determined in sections stained with anti–human CD144 and anti-Dapi antibodies (100×/oil immersion, Olympus BX51; Olympus). (C) Human LAGλ-1 MM cells coinjected with THP-1 monocytes express VEC genes that are markedly reduced in the presence of anti-PTN antibodies. (i) Human LAGλ-1 MM cells were injected subcutaneously alone or in combination with THP-1 monocytes into mice. Six weeks later, tumors were excised and RNA was extracted. Expression of Tie-2, Flk-1, VWF, CD144, and GAPDH was determined using RT-PCR. (ii) Similarly, human LAGλ-1 MM or THP-1 cells were each injected subcutaneously alone or together into mice also treated twice weekly with intraperitoneal injections of either polyclonal goat anti–human PTN antibodies or control preimmune goat IgG. Six weeks later, tumors were excised and RNA was extracted. Tie-2 and GAPDH expression was determined using RT-PCR.

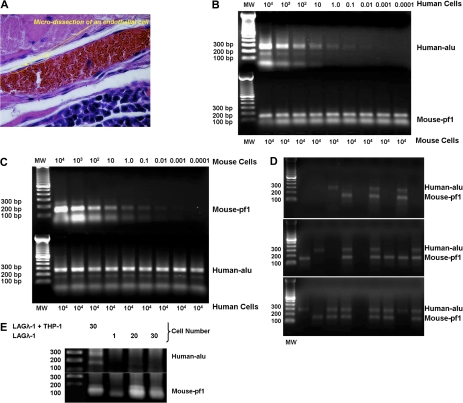

PBMCs that incorporate into blood vessels may result from fusion with endogenous already present VECs. Previous studies show differentiation of these blood vessel lining cells from circulating hematopoietic cells also may occur without cell fusion.8 Thus, we determined the proportion of cells that line blood vessels in LAGλ-1/THP-1 xenografts that contain human specific alu common repeat sequences,43,44 mouse specific pf1 sequences,44,45 or both species' sequences using microdissection of individual cells with laser capture41,42 (Figure 7A) followed by PCR amplification with species-specific primer pairs. To determine the sensitivity to identify human or mouse DNA, we serially diluted human or mouse DNA and could detect 0.01 cell equivalents of either human or mouse DNA as shown in Figure 7B and C, respectively. Analysis of single cells (n = 31) lining blood vessels from LAGλ-1 tumors containing THP-1 cells showed that 23% of the cells expressed only human gene product, 32% of lining cells showed both human and mouse sequences, and the remainder of the cells (45%) demonstrated only murine sequences (Figure 7D and data not shown). These results show some of the human monocytes have become incorporated into the walls of tumor blood vessels without fusing to murine cells, whereas other microdissected lining cells contain mixed human/mouse DNA suggesting that cell-cell fusion may also contribute to the presence of some of the human monocytes lining the tumor blood vessels. To eliminate the possibility that cells containing both types of DNA resulted from contamination with surrounding human LAGλ-1 and not cell-cell fusion, we performed PCR on single cells that were microdissected from vessels derived from LAGλ-1 without THP-1 and then combined together into 20 and 30 cell samples. These cells showed the presence of only murine DNA (Figure 7E).

Figure 7.

Microdissection of single cells lining blood vessels from LAGλ-1 tumors containing THP-1 cells shows cells with the presence of 3 different types of DNA: only human, both human and mouse, and only murine sequences. (A) Single cells were microdissected from the lining of tumor blood vessels from mice injected with LAGλ-1 and THP-1 cells (100×/objective lens, Olympus BX51; Olympus). (B) To test the sensitivity to detect human DNA with the human-specific alu primers with PCR, we serially diluted human monocytes from 104 to less than a single cell with mouse liver cells. DNA was isolated with salmon sperm DNA protection and separated on 1% agarose gel following 40 cycles of PCR with human alu–specific or mouse pf1–specific primers. The results show that human-specific alu DNA can be detected to a sensitivity of 0.01 human cell equivalents. (C) Similarly, we determined the sensitivity to detect mouse-specific pf1 DNA by serially diluting mouse liver cells in human cells (U266 MM cell line). The results show that mouse-specific pf1 DNA can be detected to a sensitivity of 0.01 mouse cell equivalents. (D) Single cells were microdissected from tumor blood vessels derived from mice coinjected with LAGλ-1 and THP-1 cells, and DNA was isolated with salmon sperm DNA protection and separated on 1% agarose gel following 40 cycles of PCR with human alu–specific or mouse pf1–specific primers. Three different patterns of PCR-amplified products were identified: human DNA alone, mouse DNA alone, and both human and mouse DNA. (E) Single cells were microdissected from the lining of tumor blood vessels from mice injected subcutaneously with LAGλ-1 + THP-1 cells. DNA was isolated with salmon sperm DNA protection and separated on 1% agarose gel following 40 cycles of PCR with human alu–specific or mouse pf1–specific primers. The lanes containing 20 and 30 cells were derived from microdissected single cells that were combined together for PCR analysis. Single cells lining the tumor blood vessels derived from mice injected with human LAGλ-1 cells alone showed the presence of only mouse DNA in tumor blood vessels, whereas mice injected with LAGλ-1 and THP-1 cells together showed the presence of both human and mouse DNA.

Discussion

Blood vessel formation may occur through angiogenesis defined as the sprouting of endothelium from preexisting vasculature, or vasculogenesis in which entirely new vessels develop.27 Endothelial cells recruited to tumors provide the tumor with new blood vessels that are critical to cancer growth and survival.6 Therefore, targeting both the cancer and endothelial cells for elimination within a tumor may be more effective than treating the tumor population alone. Promising recent clinical results evaluating the combination of antiangiogenic therapy with chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with a variety of cancers support this treatment approach.27,47,48

Several groups have identified bone marrow–derived endothelial precursor cells and demonstrated that myeloid progenitor, dendritic, and mononuclear cells can differentiate into cells of the endothelial lineage.3,6–9,46,49–51 These new endothelial cells circulate and ultimately contribute to blood vessel formation during tumor development and metastasis.49,52 However, the origin of cells that ultimately line tumor blood vessels and specific proteins required for tumor vasculogenesis remain unclear.

A recently published study suggests that some of the malignant plasma cells from MM patients may also show endothelial cell features.53 As a result, we determined whether MM cells (106) can also transdifferentiate into endothelial cells and found that treatment with PTN and M-CSF did not induce expression of VEC genes in U266, RPMI8226, or LAGλ-1 MM cells as determined by RT-PCR with CD144 and Tie-2 primers (data not shown).

In addition to stimulating proliferation of endothelial cells, VEGF promotes survival of this cell population and this depends on its interaction with VEGF receptors (VEGFRs), neuropilin-1, and VE-cadherin (CD144) as well as downstream signaling through a variety of molecules including β-catenin.28,54 Notably, withdrawal of VEGF results in apoptosis in only newly formed tumor vessels and the developing vasculature of the neonatal mouse.55

M-CSF leads to monocyte survival, monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation, and macrophage proliferation. Its expression is increased in tumors56 and the expression of the M-CSF receptor, c-fms, a protein with tyrosine kinase activity, is found on the surface of macrophages. Local expression of M-CSF in breast cancer attracts monocytes and macrophages to the tumors and also increases formation of metastatic loci.57 Knocking out this cytokine protects against metastases in this model. M-CSF stimulates endothelial cell differentiation, induces VEGF production, and shows angiogenic activity,58 and, thus, plays several roles in enhancing blood vessel formation and specifically in tumor angiogenesis.34

PTN is a regulatory cytokine that stimulates early development of blood vessels and neurons.14–16 Its expression begins during early embryogenesis, peaks at the time of birth, and sharply declines thereafter showing a very restricted expression pattern in adults. PTN is, however, highly re-expressed in tumor cells and sites of ischemic injury. Many tumor cell lines and different types of freshly derived tumors including MM, choriocarcinoma, and breast, pancreatic, colon, ovarian, and prostate cancers highly express PTN.16–19,21 Recent studies have also shown the important role of PTN in new blood vessel development13,16,59,60 and in PTN-stimulated tumor angiogenesis.17,20 PTN is also a factor important in many other functions required for the growth and maintenance of cancers including proliferation, survival, invasion, and metastasis of tumor cells as well as remodeling of the tumor microenvironment.17,21,61 This protein has been recently shown to be regulated by tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN), and deletion of PTEN increases PTN gene transcription and tumorigenicity in mouse models.62 A recently published study also demonstrated that angiogenesis is regulated through the effects of fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 on PTN.59

In this study, we have defined the critical role of PTN in tumor-directed blood vessel formation uncovering a novel mechanism of tumor vasculogenesis involving transdifferentiation of monocytes into VECs that become incorporated into tumor blood vessels. In a recent study in collaboration with members of our group,50 it was also shown that Ptn introduced into cells of a monocyte cell line induces their expression of VEC genes that incorporate into developing normal vasculature. We have now shown that the secretion of this cytokine from unmanipulated MM tumor cells transdifferentiates monocytes into endothelial cells both in vitro and in vivo, and these cells are incorporated into tumor blood vessels in vivo. We also define the previously unrecognized requirement for M-CSF in this transdifferentiation process. In addition, these studies show that another angiogenic factor, VEGF, enhances this effect. These cytokines, all 3 of which are present at high levels in the tumor environment in MM patients, play critical roles in the early development of VECs.63,64 Using human malignant cells that secrete PTN and, through the use of anti-PTN antibody, our results establish that this cytokine is required to induce the vascular phenotype in monocytes and for these cells to incorporate into vascular endothelium within human MM tumors. Thus, this study identifies PTN as a critical protein that contributes to blood vessel formation in human MM by inducing the formation of VECs from monocytes. In this context, and, consistent with earlier studies,20 inappropriate expression of PTN in malignant cells is likely to be important in the earliest events involved in the “angiogenic switch.”

Tumor-associated neovascularization is an important step in the process of tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. PTN gene expression was significantly up-regulated in corneal neovascularization as identified through gene array profiling and confirmed by RT-PCR.65 Inhibition of PTN may provide an additional novel treatment for reducing tumor blood vessel formation resulting in a decrease in cancer invasion and metastasis.

CD45 is the common leukocyte antigen, which is expressed by some monocytes and macrophages (Figure 4B), whereas CD133 is expressed in the early developmental stages of endothelial cells, so-called endothelial progenitor cells, but not on mature endothelial cells.66,67 We examined whether the expression of these surface proteins changes following exposure to PTN and/or M-CSF. CD45 expression was decreased upon stimulation with PTN and M-CSF but especially when the cells were stimulated with both cytokines consistent with their change to a nonmyeloid lineage. Furthermore, PTN and M-CSF induced increased CD133 expression in monocytes consistent with their entry into the endothelial cell lineage. Whether some of the cells ultimately expressing VEC genes lose CD133 expression, suggesting their maturation into later stages of endothelial cell development following exposure to PTN and M-CSF, remains to be determined and is the subject of current studies in the laboratory. We are also determining whether the transdifferentiation of monocytes into endothelial cells occurs through monocytes becoming less differentiated so that they become more pluripotent and capable of differentiating into endothelial progenitor cells as our CD133 expression data suggests (Figure 4A) or involves a change directly from a mature monocyte into a mature endothelial cell without requiring that the monocytes first become less differentiated.

In this study, we have identified PTN as a key player required for the earliest events involved in blood vessel formation within MM. These results suggest that combining a treatment that reduces this cytokine's function with agents that block VEGF resulting in inhibition of the later stages of blood vessel formation may improve upon the already demonstrated benefit of antiangiogenic approaches.27,47,48 Since PTN is expressed and secreted by many types of tumors,16–19 it is possible that combinations of agents that block PTN and VEGF may be effective for the treatment of many tumor types in addition to MM. We have already reported that antibodies to either PTN or VEGF alone prevent human MM growth in SCID mice,21,30 and are currently evaluating preclinically the combination of these antibodies for the treatment of MM as well as a variety of types of solid tumors. The uncovering of this novel mechanism through which early blood vessels form within MM tumors, transdifferentiation of monocytes into vascular endothelial cells induced by tumor-produced PTN and M-CSF, is likely to open up new approaches to antiangiogenic therapies in the future.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Christine Pan James for preparing and editing the paper. We thank Regina A. Swift, RN, and Joanna Wilson, RN, for preparing bone marrow and blood samples. We also thank Geoffrey Gee, Nuhad Barakat, and Carmen Malouf for administrative support of this work.

This research was supported by the Skirball Foundation, Annenberg Foundation (Los Angeles, CA), Kramer Foundation (San Francisco, CA), and Myeloma Research Fund (San Jose, CA).

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: H.C. contributed to the design, execution, and analysis of experiments and cowrote the paper; R.A.C. contributed to the design and performance of all in vivo assays and edited the paper; C.S.W., J.L., M.L., M.S., A.B., J. Steinberg, and D.S. conducted experiments related to cell culture, PCR, Western blot, ELISA, immunohistochemistry, and IFA; E.S. performed the in vivo assays; Z.Z. performed RT-PCR and THP-1 monocyte GFP labeling; D.G. and J. Said contributed to microdissection of single cells and helped to analyze the immunohistochemistry and IFA results; T.F.D., R.J.B., B.B., P.P.-P., and Y.C. helped design the experiments, analyze the data, and review the paper; and J.R.B. supervised all aspects of the project and cowrote and edited the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: James R. Berenson, Institute for Myeloma & Bone Cancer Research, 9201 West Sunset Boulevard, Suite 300, West Hollywood, CA 90069; e-mail: jberenson@imbcr.org.

References

- 1.Bertolini F, Shaked Y, Mancuso P, Kerbel RS. The multifaceted circulating endothelial cell in cancer: towards marker and target identification. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:835–845. doi: 10.1038/nrc1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isner JM, Asahara T. Angiogenesis and vasculogenesis as therapeutic strategies for postnatal neovascularization. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1231–1236. doi: 10.1172/JCI6889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi Q, Rafii S, Wu MH, et al. Evidence for circulating bone marrow-derived endothelial cells. Blood. 1998;92:362–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang S, Walker L, Afentoulis M, et al. Transplanted human bone marrow contributes to vascular endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16891–16896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404398101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H, Vakil V, Braunstein M, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells in multiple myeloma: implications and significance. Blood. 2005;105:3286–3294. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao D, Nolan DJ, Mellick AS, Bambino K, McDonnell K, Mittal V. Endothelial progenitor cells control the angiogenic switch in mouse lung metastasis. Science. 2008;319:195–198. doi: 10.1126/science.1150224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehman J, Li J, Orschell CM, March KL. Peripheral blood “endothelial progenitor cells” are derived from monocyte/macrophages and secrete angiogenic growth factors. Circulation. 2003;107:1164–1169. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000058702.69484.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey AS, Willenbring H, Jiang S, et al. Myeloid lineage progenitors give rise to vascular endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13156–13161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604203103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conejo-Garcia JR, Benencia F, Courreges MC, et al. Tumor-infiltrating dendritic cell precursors recruited by a beta-defensin contribute to vasculogenesis under the influence of Vegf-A. Nat Med. 2004;10:950–958. doi: 10.1038/nm1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Condeelis J, Pollard JW. Macrophages: obligate partners for tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cell. 2006;124:263–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stearman RS, Dwyer-Nield L, Grady MC, Malkinson AM, Geraci MW. A macrophage gene expression signature defines a field effect in the lung tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2008;68:34–43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeh HJ, He YY, Xu J, Hsu CY, Deuel TF. Upregulation of pleiotrophin gene expression in developing microvasculature, macrophages, and astrocytes after acute ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3699–3707. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03699.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christman KL, Fang Q, Kim AJ, et al. Pleiotrophin induces formation of functional neovasculature in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332:1146–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silos-Santiago I, Yeh HJ, Gurrieri MA, et al. Localization of pleiotrophin and its mRNA in subpopulations of neurons and their corresponding axonal tracts suggests important roles in neural-glial interactions during development and in maturity. J Neurobiol. 1996;31:283–296. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199611)31:3<283::AID-NEU2>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li YS, Milner PG, Chauhan AK, et al. Cloning and expression of a developmentally regulated protein that induces mitogenic and neurite outgrowth activity. Science. 1990;250:1690–1694. doi: 10.1126/science.2270483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang N, Deuel TF. Pleiotrophin and midkine, a family of mitogenic and angiogenic heparin-binding growth and differentiation factors. Curr Opin Hematol. 1999;6:44–650. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199901000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang Y, Zuka M, Perez-Pinera P, et al. Secretion of pleiotrophin stimulates breast cancer progression through remodeling of the tumor microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10888–10893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704366104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakagawara A, Milbrandt J, Muramatsu T, et al. Differential expression of pleiotrophin and midkine in advanced neuroblastomas. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1792–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang N, Zhong R, Wang ZY, Deuel TF. Human breast cancer growth inhibited in vivo by a dominant negative pleiotrophin mutant. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16733–16736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang N, Zhong R, Perez-Pinera P, et al. Identification of the angiogenesis signaling domain in pleiotrophin defines a mechanism of the angiogenic switch. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen H, Gordon MS, Campbell RA, et al. Pleiotrophin is highly expressed by myeloma cells and promotes myeloma tumor growth. Blood. 2007;110:287–295. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-042374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeh HS, Chen H, Manyak SJ, et al. Serum pleiotrophin levels are elevated in multiple myeloma patients and correlate with disease status. Br J Haematol. 2006;133:526–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jäger R, List B, Knabbe C, et al. Serum levels of the angiogenic factor pleiotrophin in relation to disease stage in lung cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:858–863. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Souttou B, Juhl H, Hackenbruck J, et al. Relationship between serum concentrations of the growth factor pleiotrophin and pleiotrophin-positive tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1468–1473. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.19.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malerczyk C, Schulte AM, Czubayko F, et al. Ribozyme targeting of the growth factor pleiotrophin in established tumors: a gene therapy approach. Gene Ther. 2005;12:339–346. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grzelinski M, Urban-Klein B, Martens T, et al. RNA interference-mediated gene silencing of pleiotrophin through polyethylenimine-complexed small interfering RNAs in vivo exerts antitumoral effects in glioblastoma xenografts. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:751–766. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folkman J. Angiogenesis. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:1–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Podar K, Anderson KC. Inhibition of VEGF signaling pathways in multiple myeloma and other malignancies. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:538–542. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.5.3922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell RA, Sanchez E, Chen H, et al. Anti-VEGF antibody treatment markedly inhibits tumor growth in SCID-hu models of human multiple myeloma [abstract]. Blood. 2006;108:846a. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akagawa KS, Kamoshita K, Tokunaga T. Effects of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and colony-stimulating factor-1 on the proliferation and differentiation of murine alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 1988;141:3383–3390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yano S, Nishioka Y, Nokihara H, Sone S. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor gene transduction into human lung cancer cells differentially regulates metastasis formations in various organ microenvironments of natural killer cell-depleted SCID mice. Cancer Res. 1997;57:784–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frangogiannis NG, Mendoza LH, Ren G, et al. MCSF expression is induced in healing myocardial infarcts and may regulate monocyte and endothelial cell phenotype. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H483–H492. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01016.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okazaki T, Ebihara S, Takahashi H, Asada M, Kanda A, Sasaki H. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces vascular endothelial growth factor production in skeletal muscle and promotes tumor angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2005;174:7531–7538. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wurmser AE, Nakashima K, Summers RG, et al. Cell fusion-independent differentiation of neural stem cells to the endothelial lineage. Nature. 2004;430:350–356. doi: 10.1038/nature02604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoon J, Shim WJ, Ro YM, Lim DS. Transdifferentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into cardiomyocytes by direct cell-to-cell contact with neonatal cardiomyocyte but not adult cardiomyocytes. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:715–721. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-1068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kodama H, Inoue T, Watanabe R, et al. Neurogenic potential of progenitors derived from human circulating CD14+ monocytes. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006;84:209–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2006.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blondet B, Carpentier G, Lafdil F, Courty J. Pleiotrophin cellular localization in nerve regeneration after peripheral nerve injury. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:971–977. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4A6574.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalamasz D, Long SA, Taniguchi R, Buckner JH, Berenson RJ, Bonyhadi M. Optimization of human T-cell expansion ex vivo using magnetic beads conjugated with anti-CD3 and Anti-CD28 antibodies. J Immunother. 2004;27:405–418. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200409000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell RA, Manyak SJ, Yang HH, et al. LAGlambda-1: a clinically relevant drug resistant human multiple myeloma tumor murine model that enables rapid evaluation of treatments for multiple myeloma. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:1409–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emmert-Buck MR, Bonner RF, Smith PD, et al. Laser capture microdissection. Science. 1996;274:998–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simone NL, Bonner RF, Gillespie JW, Emmert-Buck MR, Liotta LA. Laser-capture microdissection: opening the microscopic frontier to molecular analysis. Trends Genet. 1998;14:272–276. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelson DL, Ledbetter SA, Corbo L, et al. Alu polymerase chain reaction: a method for rapid isolation of human-specific sequences from complex DNA sources. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:6686–6690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gronthos S, Brahim J, Li W, et al. Stem cell properties of human dental pulp stem cells. J Dent Res. 2002;81:531–535. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miura M, Gronthos S, Zhao M, et al. SHED: stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5807–5812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937635100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venneri MA, De Palma M, Ponzoni M, et al. Identification of proangiogenic TIE2-expressing monocytes (TEMs) in human peripheral blood and cancer. Blood. 2007;109:5276–5285. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-053504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dudek AZ, Bodempudi V, Welsh BW, et al. Systemic inhibition of tumour angiogenesis by endothelial cell-based gene therapy. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:513–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharifi BG, Zeng Z, Wang L, et al. Pleiotrophin induces transdifferentiation of monocytes into functional endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1273–1280. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000222017.05085.8e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peters BA, Diaz LA, Polyak K, et al. Contribution of bone marrow-derived endothelial cells to human tumor vasculature. Nat Med. 2005;11:261–262. doi: 10.1038/nm1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo K, Li J, Wang H, et al. PRL-3 initiates tumor angiogenesis by recruiting endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9625–9635. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rigolin GM, Fraulini C, Ciccone M, et al. Neoplastic circulating endothelial cells in multiple myeloma with 13q14 deletion. Blood. 2006;107:2531–2535. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loureiro RM, D'Amore PA. Transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benjamin LE, Golijanin D, Itin A, Pode D, Keshet E. Selective ablation of immature blood vessels in established human tumors follows vascular endothelial growth factor withdrawal. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:159–165. doi: 10.1172/JCI5028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sapi E. The role of CSF-1 in normal physiology of mammary gland and breast cancer: an update. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:1–11. doi: 10.1177/153537020422900101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin EY, Nguyen AV, Russell RG, Pollard JW. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J Exp Med. 2001;193:727–740. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eubank TD, Galloway M, Montague CM, Waldman WJ, Marsh CB. M-CSF induces vascular endothelial growth factor production and angiogenic activity from human monocytes. J Immunol. 2003;171:2637–2643. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magnusson PU, Dimberg A, Mellberg S, Lukinius A, Claesson-Welsh L. FGFR-1 regulates angiogenesis through cytokines interleukin-4 and pleiotrophin. Blood. 2007;110:4214–4222. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-067314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Choudhuri R, Zhang HT, Donnini S, Ziche M, Bicknell R. An angiogenic role for the neurokines midkine and pleiotrophin in tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1814–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perez-Pinera P, Chang Y, Deuel TF. Pleiotrophin, a multifunctional tumor promoter through induction of tumor angiogenesis, remodeling of the tumor microenvironment, and activation of stromal fibroblasts. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2877–2883. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.23.5090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li G, Hu Y, Huo Y, et al. PTEN deletion leads to up-regulation of a secreted growth factor pleiotrophin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10663–10668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Minehata K, Mukouyama YS, Sekiguchi T, Hara T, Miyajima A. Macrophage colony stimulating factor modulates the development of hematopoiesis by stimulating the differentiation of endothelial cells in the AGM region. Blood. 2002;99:2360–2368. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ng YS, Krilleke D, Shima DT. VEGF function in vascular pathogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:527–537. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Usui T, Yamagami S, Yokoo S, Mimura T, Ono K, Amano S. Gene expression profile in corneal neovascularization identified by immunology related macroarray. Mol Vis. 2004;10:832–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hristov M, Erl W, Weber PC. Endothelial progenitor cells: isolation and characterization. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2003;13:201–206. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(03)00077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leong AS-Y, Cooper K. Manual of diagnostic antibodies for immunohistology. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Greenwich Medical Media; 2003. [Google Scholar]