Abstract

Bacterial heme-copper terminal oxidases react quickly with NO to form a heme-nitrosyl complex, which, in some of these enzymes, can further react with a second NO molecule to produce N2O. Previously, we characterized the heme a3-NO complex formed in cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus and the product of its low-temperature illumination. We showed that the photolyzed NO group binds to CuB(I) to form an end-on NO-CuB or side-on copper-nitrosyl complex which is likely to represent the binding characteristics of the second NO molecule at the heme-copper active site. Here we present a comparative study with cytochrome bo3 from Escherichia coli. Both terminal oxidases are shown to catalyze the same two-electron reduction of NO to N2O. The EPR and resonance Raman signatures of the heme o3-NO complex are comparable to those of the a3-NO complex. However, low-temperature FTIR experiments reveal that photolysis of the heme o3-NO complex does not produce a CuB-nitrosyl complex, but that instead, the NO remains unbound in the active-site cavity. Additional FTIR photolysis experiments on the heme-nitrosyl complexes of these terminal oxidases, in the presence of CO demonstrate that an [o3–NO • OC–CuB] tertiary complex can form in bo3 but not in ba3. We assign these differences to a greater iron-copper distance in the reduced form of bo3 compared to that of ba3. Because this difference in metal-metal distance does not appear to affect the NO reductase activity, our results suggest that the coordination of the second NO to CuB is not an essential step of the reaction mechanism.

The reduction of nitric oxide (NO) to nitrous oxide (N2O) (eq. 1) is an obligatory step in the bacterial denitrification pathway which converts nitrate to atmospheric nitrogen.

| (1) |

Denitrifying NO reductases found in many prokaryotes, including symbiotic and pathogenic bacteria, have been shown to provide those microorganisms resistance to the mammalian immune response. For example, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis, the causative agents of meningococcal disease in humans, depend upon NO reductases to tolerate toxic concentrations of NO (1–3). These integral protein complexes contain a NorB subunit evolutionarily related to subunit I of heme-copper terminal oxidases (4, 5). There are no crystal structures available for NO reductases (NORs) yet, but sequence alignments and hydropathy plots suggest that the six histidine side chains involved in ligating metal cofactors in terminal oxidases are conserved in norB (6). While O2 reduction in terminal oxidases occurs at a heme-copper dinuclear site, the reduction of NO by NOR takes place at a heme-nonheme diiron center (7–11). Despite the difference in metal composition, several heme-copper terminal oxidases (i.e., ba3, bo3, and cbb3) are capable of catalyzing the reduction of NO albeit with much lower turnover rates compared to NORs (12–14). This low NO reductase activity is unlikely to be the primary function of these enzymes, but studying their interaction with NO can expand our knowledge of NO reduction mechanisms in NOR and, more generally, in dinuclear active centers.

The catalytic mechanism of NO reduction in terminal oxidases is generally considered to be initiated by the binding of NO to the high-spin heme in the fully-reduced enzyme. Subsequent steps are expected to involve CuB, either as a coordination site for a second molecule of NO or as an electron donor and electrostatic partner to a heme-hyponitrite complex [Fe(III)-N2O22− •CuB(II)] (11, 15–17). Vos and coworkers have monitored the rebinding kinetics of the photolyzed NO in ba3-NO at room temperature and interpreted the lack of significant subnanosecond NO rebinding to heme a3 as evidence of the photolyzed NO binding to CuB before rebinding to the heme a3. (18). In our subsequent FTIR photolysis study of ba3-NO at cryogenic temperature, we observed the formation of a CuB-nitrosyl species with an unusual N-O stretching frequency suggestive of an O-bound (η1-O) or side-on (η2-NO) configuration (17). The characterization of this complex suggests that the N-N bond formation in ba3 does not proceed from a transient [a3-NO • ON-CuB] trans ba3-(NO)2 complex as proposed by Ohta and coworkers (15). Indeed, if an N-bound CuB-nitrosyl was the species formed in the transient ba3-(NO)2 complex, one would expect the photoinduced CuB-nitrosyl complex to adopt this geometry even in the absence of the heme a3-NO species nearby.

In light of these results, it is tempting to speculate that the photoinduced CuB-nitrosyl species generated in ba3-NO describes the mode of binding of the second NO molecule. To determine whether the hypothesis drawn from the results with ba3 applies to other terminal oxidases with NO reductase activity, we now direct our work to the bo3 quinol oxidase from Escherichia coli. A few investigations have been focused on the interaction of NO with bo3 from E. coli. Sarti and coworkers measured a low but significant NO reductase activity in bo3 under reducing conditions (14). On the basis of EPR data, Thomson and coworkers have proposed that two NO molecules bind to CuB(II) in the oxidized form of bo3 (19). To our knowledge, cytochrome bo3 is the only quinol oxidase reported to exhibit NO reductase activity, and as such, it provides a relevant model for the quinol NOR (qNOR) from N. gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis (3).

Here we report cryogenic FTIR photolysis experiments on fully reduced bo3-NO and the mixed gas bo3-CO/NO complexes. Amperometric measurements of NO concentrations and monitoring of N2O production by FTIR spectroscopy demonstrate that ba3 and bo3 catalyze the same reaction at similar rates. However, the CuB-nitrosyl species observed in ba3-NO does not form in bo3-NO. Instead, the photolyzed NO of the latter docks at a protein pocket that leads to efficient NO geminate recombination similar to that in ferrous myoglobin-NO (20). FTIR experiments, carried out on ba3 and bo3 exposed to NO/CO mixed gas, show concomitant binding of two diatomic molecules only in the dinuclear site of bo3 to form a [o3-NO • OC-CuB] tertiary complex. The relevance of this [o3-NO • OC-CuB] state to the NO reductase activity in cytochrome bo3 is discussed in the context of other terminal oxidases and of denitrifying NO reductases.

Materials and methods

Protein stock solutions

The expression and purification of aa3, ba3 and bo3 were performed as previously described (21, 22). For all experiments, cytochrome aa3 and ba3 were in 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.4 and 0.1% dodecyl β-D-maltoside, and 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 with 0.05% dodecyl β-D-maltoside, respectively. Cytochrome bo3 was in 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 8.0 with 0.1% dodecyl β-D-maltoside, 10 mM EDTA, and 5% glycerol.

NO reductase activity measurements

NO stock solutions were prepared by bubbling of NO gas, previously treated with 1 M KOH, into double-distilled water in an anaerobically-sealed vessel for ~15 min at 25°C. The concentration of NO in the solution was determined to be 1.5 mM by titration against ferrous Mb. NO reduction measurements were carried out with a Clark-type NO electrode equipped with a 2 ml gas-tight sample chamber at 20°C in a glove box containing less than 1ppm O2 (Omnilab System, Vacuum Atmospheres Company). The current was stabilized with a buffer solution containing 10 mM ascorbate and 0.1 mM N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD) in the sample chamber, followed by three successive additions of saturated NO solution to reach final NO concentrations of 40 to 60 μM. After stabilization of the NO solution, the reduced enzyme was added to reach a final concentration of 7 μM. The current was monitored until it returned to zero.

N2O production measurements

The production of N2O by the two terminal oxidases was monitored using the ν(NNO) stretch at 2230 cm−1 in the FTIR spectra (23). Protein solutions were made anaerobic by prolonged purging with argon on a Schlenk line and brought to a final enzyme concentration of 50 μM with 10 mM ascorbate and 0.1 mM TMPD in the glove box. A diethylamine NONOate (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) stock solution, in 0.01 M NaOH, was prepared based on its ε250 nm = 9180 M−1 cm−1 extinction coefficient and an aliquot was used to confirm the concentration of the NO produced by monitoring the conversion of deoxymyoglobin to the nitrosyl complex. Quickly after the addition of NONOate to the protein solution, a 33-μL droplet of sample was deposited on a CaF2 window and a second CaF2 window was dropped on the sample. The optical pathlength was controlled by a 100-μm Teflon spacer. The FTIR cell was placed in the sample compartment of the FTIR instrument. FTIR spectra were obtained on a Perkin-Elmer system 2000 equipped with a liquid-N2-cooled MCT detector and purged with compressed air, dried, and depleted of CO2 (Purge gas generator, puregas LLC). Sets of 100 scans accumulations were acquired every 2 min, at a 4-cm−1 resolution, until no further growth of the N2O IR band was observed. These data were compared to a calibration curve obtained from solutions with varying N2O concentrations.

EPR experiments

EPR spectra were obtained on a Bruker E500 X-band EPR spectrometer equipped with a superX microwave bridge and a dual mode cavity with a helium flow cryostat (ESR900, Oxford Instruments, Inc.). The microwave power, modulation amplitude, magnetic field sweep, and the sample temperature were varied to optimize the detection of all potential EPR active species before and after illumination of the nitrosyl complexes.

RR experiments

Typical enzyme concentrations used were 150 μM. The RR spectra were obtained using a custom McPherson 2061/207 spectrograph (set at 0.67 m with variable gratings) equipped with a Princeton Instruments liquid-N2-cooled CCD detector (LN-1100PB). Kaiser Optical supernotch filters were used to attenuate Rayleigh scattering generated by the 413-nm excitation of an Innova 302 krypton laser (Coherent, Santa Clara CA). Spectra were collected using a 90° scattering geometry on room-temperature samples mounted on a reciprocating translation stage. Frequencies were calibrated relative to indene and aspirin standards and are accurate to ±1 cm−1. Polarization conditions were optimized using CCl4. The integrity of the RR samples, before and after illumination, was confirmed by direct monitoring of their UV-vis spectra in Raman capillaries.

FTIR photolysis experiments

FTIR photolysis experiments were carried out as previously described (17). After prolonged purging with argon on a Schlenk line, the sample was fully reduced by addition of 10 mM dithionite in an anaerobic glove box. NO gas (14NO from Airgas and Aldrich, 15NO from ICON), initially treated with 1 M KOH solution, was added to the sample headspace to achieve an NO partial pressure of 0.1 atm. After 1 min of incubation at room temperature, 15 μL of the protein solution was deposited as a droplet on a CaF2 window and a second CaF2 window was dropped on the sample using a 15-μm Teflon spacer to complete the FTIR cell.

CO/NO mixed-gas experiments were carried out on ~350 μM reduced-protein solutions containing 10 mM ascorbate, 0.1 mM TMPD, and 25% glycerol. The sample headspace was thoroughly exchanged with pure CO gas to reach saturation (12CO purchased from Airgas or 13CO purchased from ICON) and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. A few μL of a stock solution of NONOate was added to the sample to produced 3.0 equiv NO. Immediately after the addition of NONOate, a 15-μL droplet of sample was deposited on a CaF2 window with a 15-μm Teflon spacer, and a second CaF2 window was dropped on the sample to complete the IR cell. The 25% glycerol content of the sample insured minimal degassing of CO during this procedure. Alternatively, the reduced protein (with the same concentration and buffer conditions as above) was exposed to a 0.1-atm NO partial pressure for 1 min and the headspace replaced with pure CO gas and incubated for 10 min at room temperature before transferring the sample to the IR cell.

For all samples, once the IR cell was securely sealed, the presence of the desired complexes was confirmed by obtaining a UV-vis spectrum of the sample using a Cary 50 spectrophotometer (Varian). The FTIR cell was then mounted to a closed-cycle cryogenic system (Displex, Advanced Research Systems) and installed in the sample compartment of the FTIR instrument to keep in the dark while the temperature dropped to 30 K. The temperature of the sample was monitored and controlled with a Cry-Con 32 unit. Sets of 1000-scan accumulations were acquired at a 4 cm−1 resolution by the Perkin-Elmer system 2000. Photolysis of the nitrosyl and carbonyl complexes was achieved with continuous illumination of the sample directly in the FTIR sample chamber with a 50 W tungsten lamp after filtering out heat and NIR emission. This same illumination procedure was used to follow the dissociation and rebinding processes by UV-vis absorption spectroscopy with a Cary-50 spectrometer.

The reversibility of the photolysis events studied here was confirmed by comparing successive ‘dark’ and ‘illuminated’ UV-vis absorption spectra, and ‘dark’ minus ‘illuminated’ FTIR difference spectra obtained at 30 K after raising the temperature of the sample. A first evaluation of the temperature dependence of the rebinding process was obtained by UV-vis absorption, raising the sample temperature incrementally by 10 K until the return of the ‘dark’ spectrum was observed. The comparison of a first ‘dark’ minus ‘illuminated’ FTIR difference spectrum obtained at 30 K with a second 30-K difference spectra obtained after an incubation period at higher temperature, referred to below as annealing temperature, provides a reliable means to compare rebinding-temperatures between distinct photolabile species.

Results

NO reductase activity measurements

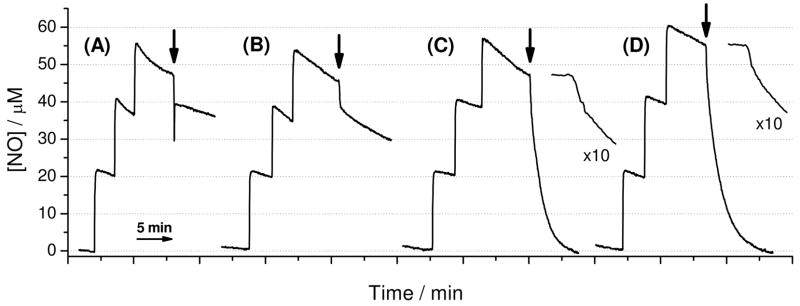

While both ba3 and bo3 have been reported to possess NO reductase activity (12, 14), their steady-state turnover rates have not been compared in side-by-side experiments. Thus, we carried out parallel NO reductase activity measurements on ba3 and bo3 by monitoring NO consumption amperometrically under reducing conditions (10 mM ascorbate and 0.1 mM TMPD) (Figure 1). Upon addition of myoglobin, aa3, ba3, and bo3 to the NO solutions, a rapid initial decay of current is assigned to the stoichiometric binding of NO to ferrous high-spin hemes. While no further current change was observed with myoglobin and aa3, ba3 and bo3 displayed NO consumption with initial rates of 3.4 mol NO/mol ba3-min and 2.6 mol NO/mol bo3-min, respectively, at [NO] = 40 μM (Figure 1). These values match that previously reported by Giuffre et al. (3.0 ± 0.7 mol NO/mol ba3-min at [NO] = 55 μM) (12) and complement the measurement by Butler et al. (0.3 mol NO/mol bo3-min at [NO] = 5 μM) (14). It is worth noting that, in the presence of excess reducing agent, both enzymes remained as mononitrosyl complexes after the turnover measurements (data not shown). This observation indicates that, in both enzymes, the binding affinity for the second NO is much lower than that of the first NO.

Figure 1.

NO binding and reductase activity of ferrous myoglobin (A), aa3 (B), ba3 (C), and bo3 (D) at 25°C. Black arrows show time points where each enzyme were added to react a final concentration of 7 μM. For ba3 and bo3, the early part of the trace is also shown expanded 10-times to reveal the initial NO-binding steps.

The production of N2O was monitored by the FTIR measurement of the antisymmetric N-N-O stretch mode ν3 of N2O at 2231 cm−1. Using calibration curves with N2O-saturated solutions, the 2231-cm−1 absorption values of the ba3 and bo3 solutions confirm that all of the NO consumed is converted to N2O. (Figure S1). As expected, N2O was not detected in FTIR measurements when the terminal oxidases were replaced by myoglobin (data not shown).

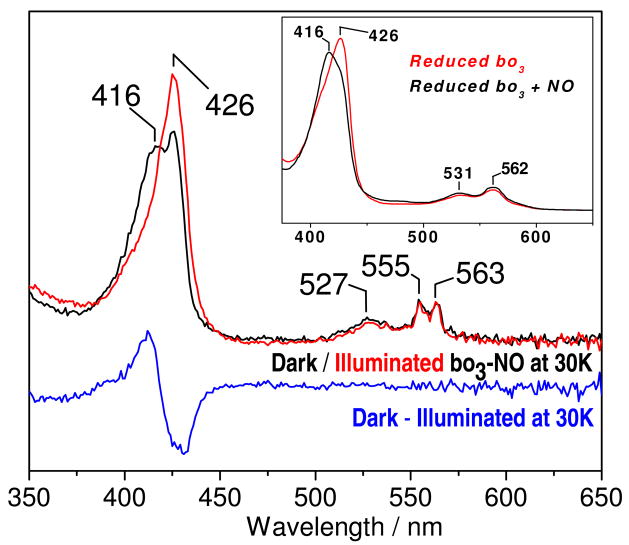

UV-vis, EPR and RR characterization of bo3-NO

Exposure of fully-reduced bo3 to a headspace containing 0.1 atm NO results in the rapid formation of bo3-NO. The Fe(II) heme-o3 Soret absorption at 426 nm is blue-shifted to generate a new Soret band at 416 nm, and there are only minor changes in the visible range of the room-temperature absorption spectra (Figure 2, inset). The Soret absorption at 416 nm, assigned to the heme-o3-NO complex, is also observed at 30 K, but disappears following illumination (Figure 2). As reported previously (24), the EPR spectrum of the bo3-NO complex is characteristic of a 6-coordinate low-spin heme iron(II)-nitrosyl species with g values centered around 2 (2.102, 2.01, 1.99) and nine-line 14N-hyperfine structure (ANO = 20 G, AHis = 6 G) equivalent to signals observed in ba3-NO (Figure S2). In addition, this EPR spectrum includes an easily saturated, isotropic g = 2.005 with a 10 G linewidth which was previously assigned to a semi-quinone radical (25, 26). Unlike the EPR features associated with the heme o3-NO, this signal is insensitive to short illumination at cryogenic temperatures (Figure S2). The only new EPR signal observed after illumination is that of free NO at g = 1.97, which is best observed at high microwave power and below 10 K (data not shown).

Figure 2.

UV-vis spectra in dark (black) and illuminated (red) and dark minus illuminated difference spectra (blue) of bo3-NO complex at 30 K. The inset shows the room temperature UV-vis spectra of reduced bo3 (red) and the bo3-NO complex (black).

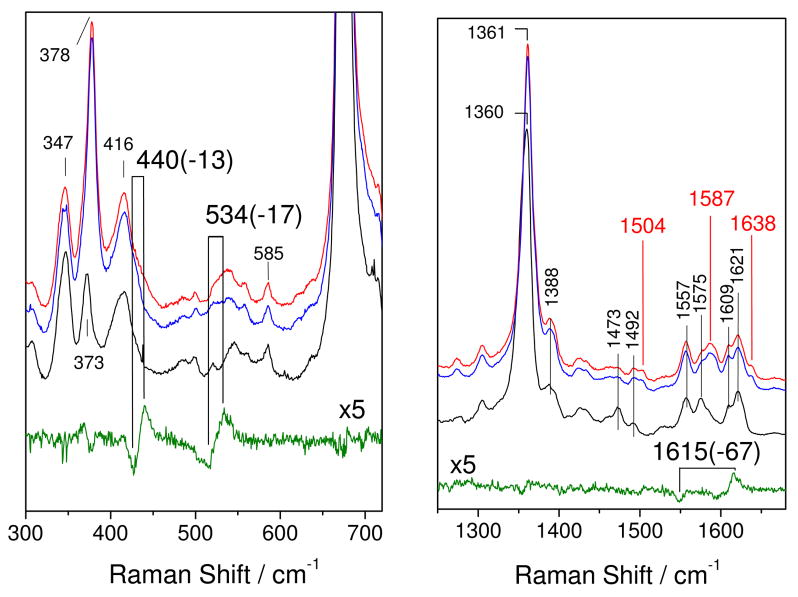

RR spectra of the bo3-NO complex, obtained with a 413-nm excitation at room temperature, display enhancement of vibrational modes from the heme o3-NO complex (Figure 3). The porphyrin skeletal modes ν4, ν3, ν2, and ν10 at 1361, 1504, 1587, and 1638 cm−1, respectively, are characteristic of a 6-coordinate low-spin heme-nitrosyl species. Vibrational modes involving the Fe-N-O unit are indentified by their 15N18O-downshifts (Figure 3). The ν(N-O)o3 mode is observed at 1615 cm−1 and exhibits a 67-cm−1 downshift with 15N18O that is within 5-cm−1 of the calculated shift for a diatomic N-O oscillator. Two bands, at 534 (−17) and 440 (−13) cm−1, are assigned to ν(Fe-NO) and δ(Fe-NO) modes, respectively, even though significant mixing exists between these two modes (27–29). The unusually intense d(Fe-NO) band, which is not observed in ba3-NO (17, 30), and the low ν(Fe-NO) frequency suggest that the Fe-N-O angle is smaller than the 140° equilibrium value. The low ν(N-O)o3 frequency is also consistent with a small Fe-N-O angle which favors the Fe(III)NO− resonance structure and N-O double-bond character.

Figure 3.

Low- and high-frequency RR spectra of bo3-14N16O (red), bo3-15N18O (blue), reduced bo3 (black), and the bo3-14N16O minus bo3-15N18O difference spectrum (green) obtained with a 413-nm excitation at room temperature (protein concentration ~150 μM).

Low-temperature FTIR photolysis of the bo3-NO and bo3-(NO)(CO) complexes

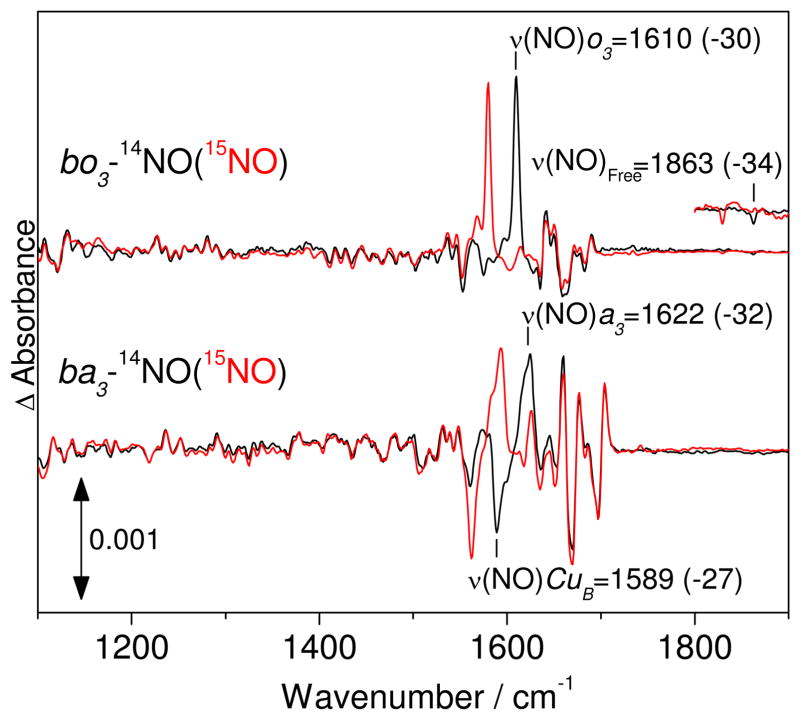

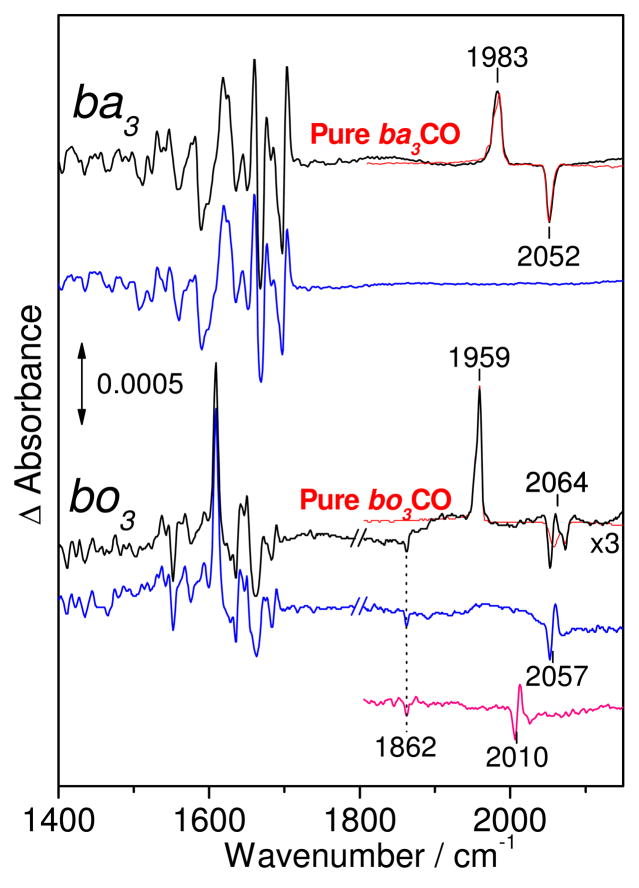

Previously, we used photolysis experiments with ba3-NO at 30 K to isolate ν(N-O) vibrations in ‘dark’ minus ‘illuminated’ FTIR difference spectra (17). These experiments revealed that the disappearance of the ν(N-O)a3 at 1622 cm−1, consistent with the dissociation of NO from the heme and accompanied by the formation of a CuB-nitrosyl complex with a negative ν(N-O)CuB at 1589 cm−1. In the case of bo3-NO, the FTIR ‘dark’ minus ‘illuminated’ difference spectra show a sharp positive band at 1610 cm−1 that is readily assigned to the ν(N-O)o3 by its 30-cm−1 downshift with 15NO, but there are no negative signals suggestive of a CuB-nitrosyl species (Figure 4). Instead, a negative band at 1863 cm−1 that shifts -34 cm−1 with 15NO is characteristic of a ν(N-O) from an NO molecule docked in a proteinaceous pocket, as observed with the nitrosyl complex of myoglobin (20). Varying buffer and salt conditions had no effect on the FTIR difference spectra of bo3-NO (Figure S3). Thus, these experiments suggest that, despite the structural similarities of the heme-copper sites in these terminal oxidases (31, 32) and their efficient capture of photolyzed CO by CuB(I) in both terminal oxidases, NO transfer from heme to CuB does not occur in bo3. This interpretation is also supported by a difference between bo3-NO and ba3-NO in their temperature dependence for geminate rebinding of NO. Indeed, after a first illumination at 30 K, the photolyzed ba3-NO complex must be annealed to 90 K to recover the full amplitude of the ‘dark’ minus ‘illuminated’ FTIR difference spectrum (17), whereas the temperature only needs to be raised to 60 K to allow complete rebinding of NO to heme o3 in bo3-NO (data not shown).

Figure 4.

FTIR difference spectra (‘dark’ minus ‘illuminated’) of bo3-NO (top traces) and ba3-NO (bottom traces) at 30 K. The spectra were obtained with protein concentration near 350 μM and were normalized based on the room temperature UV-vis spectra obtained directly from the FTIR cell (15 μm pathlength).

To gain further insight into the catalytically-relevant step in which two NO molecules interact with the heme-copper, and anticipating the formation of a non-reactive [(heme-copper)(NO)(CO)] tertiary complex, we carried out experiments on reduced ba3 and bo3 proteins with consecutive exposure of to CO and NO gases. These experiments succeeded in forming a [o3-NO • OC-CuB] complex in bo3. In ba3, exposure of ba3-CO, in the presence of excess CO, to 3 equiv of NO minutes before freezing (see experimental section) resulted in the formation of ba3-NO and ba3-CO complexes that were easily distinguishable in the FTIR spectra (Figure 5). While rebinding of the photolyzed CO required annealing the sample above 220 K, the rebinding of NO was complete after annealing at 100 K. This difference in rebinding temperature allows the separation of FTIR features associated with ba3-NO and ba3-CO. When the same experiment was carried out with bo3, features in the FTIR difference spectra associated with bo3-NO and bo3-CO complexes were also observed; however, the NO dissociation process induces a differential signal in the ν(C-O)CuB region that shifts –47 cm−1 with 13CO (Figure 5). We assign this signal, centered at 2057 cm−1, to a perturbation of the CuB-carbonyl as NO is dissociated from heme o3. The ν(NO)o3 in these mixed-gas experiments is observed at 1610 cm−1 and is indistinguishable from the ν(NO)o3 observed when the complex is formed with pure NO. The relative intensities of the ν(N-O)o3 and ν(C-O)o3 bands suggest that the active site in the bo3-CO state represents only 10% of the sample, while the remaining 90% contains the heme o3-NO complex. Furthermore, on the basis of the ν(C-O)CuB band observed in the ‘dark’ spectrum (Figure 6), we estimate that out of the 90% of nitrosylated active site, at least 10% binds CO to form the [o3-NO • OC-CuB] complex. Thus, although the active site of bo3 cannot bind two CO molecules at the same time, binding of NO to heme a3 allows the subsequent binding of CO to CuB. The ν(C-O)CuB band in the [o3-NO • OC-CuB] complex is symmetric and centered at 2057 cm−1, which contrasts the multiple conformers observed in the light-induced [o3 • OC-CuB] state (Figure 6). Changing the order of gas exposure by forming the heme-nitrosyl complexes before the addition of excess CO had no effect on the FTIR data obtained with bo3 and ba3 (data not shown).

Figure 5.

FTIR difference spectra (‘dark’ minus ‘illuminated’) of ba3-CO/NO (top) and bo3-CO/NO (bottom), before (black) and after annealing at 120 K (blue). Also shown for comparison, are the ‘dark’ minus ‘illuminated’ difference spectra for the pure-CO complexes (red traces) and the bo3-13CO/NO difference spectra after illumination and annealing at 120 (pink). The spectra were obtained with protein concentration near 350 μM and were normalized based on the room temperature UV-vis spectra obtained directly from the FTIR cell (15 μm pathlength).

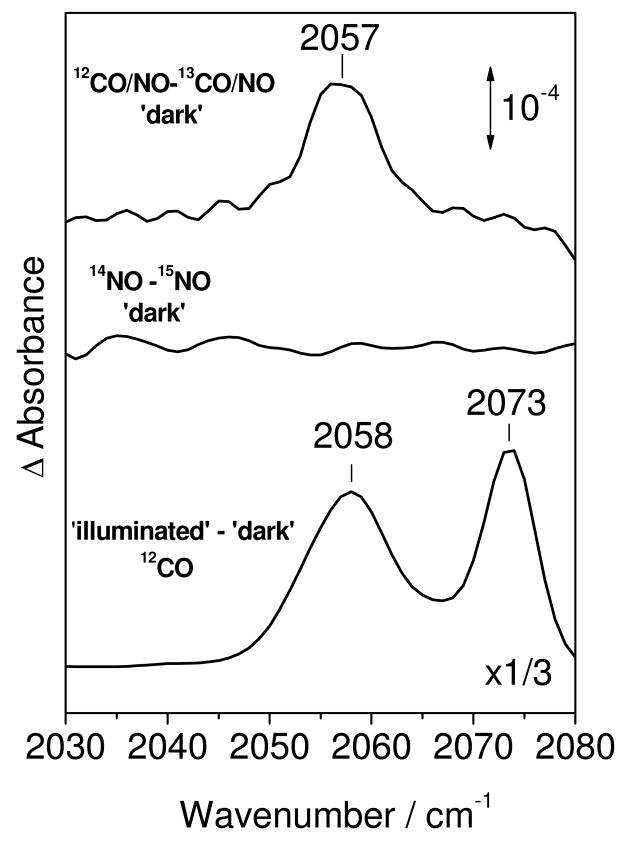

Figure 6.

Comparison of FTIR difference spectra in the range of the ν(12C-O)CuB modes in bo3. From top to bottom: 12CO minus 13CO difference spectrum from the ‘dark’ bo3-CO/NO (black), 14NO minus 15NO difference spectrum from the ‘dark’ bo3-NO (red), and ‘illuminated’ minus ‘dark’ bo3-12CO (bottom, black). The spectra were obtained with protein concentration near 350 μM and were normalized based on the room temperature UV-vis spectra obtained directly from the FTIR cell (15 μm pathlength).

Discussion

Numerous studies with fully-reduced terminal oxidases have shown that the five-coordinated ferrous high-spin heme efficiently binds NO to form a stable ferrous low-spin nitrosyl complex (33–38). Several terminal oxidases, including T. theromophilus ba3 and E. coli bo3, have been shown to further react with a second NO molecule to catalyze the reduction of NO to N2O (12, 14). Recently, we reported the formation of a photoinduced CuB-nitrosyl species with an end-on NO-CuB or a side-on CuB-nitrosyl configuration in ba3 at cryogenic temperature (17) and proposed that this species reflects the binding geometry of the second NO molecule involved in the NO reductase reaction catalyzed by ba3 (17). In the present work, we show that the bo3 quinol oxidase from E. coli reduces NO at a rate equivalent to that of ba3 (~3 mol NO/[E] mol-min at [NO] = 40 μM). In analogy to ba3, a stable 6-coordinate low-spin heme-o3 nitrosyl complex is observed, which exhibits Fe-N-O stretching frequencies suggestive of a bent Fe-N-O geometry (27, 28). Illumination of bo3-NO at 30 K dissociates the heme-nitrosyl complex with equivalent efficiency as in ba3-NO, but complete rebinding of NO to the heme o3 occurs after annealing the sample to 60 K, which is significantly lower than the 90-K annealing temperature measured in ba3-NO (17). Thus, the photolyzed bo3-NO state is thermodynamically less favored than the corresponding nitrosyl complex in ba3. Comparison of low-temperature FTIR photolysis data for bo3-NO and ba3-NO support this conclusion. Indeed, light-induced FTIR difference spectra show that stabilization of the photolyzed NO through interactions with CuB(I) does not occur in bo3-NO as it does in ba3-NO. Rather, the photolyzed FTIR spectra of bo3-NO reveals a ν(N-O) band at 1863 cm−1 which corresponds to an NO molecule docked in a proteinaceous pocket.

What prevents the formation of a light-induced CuB-nitrosyl in bo3? Because the photolysis process with the bo3-CO complex leads to the efficient capture of the photolyzed CO by CuB, a lack of an open coordination site on CuB can be ruled out. Extensive RR and FTIR studies of the heme-copper carbonyl complexes have revealed different configurations, which have been named α, β, and γ forms that correspond to increasing levels of steric restrictions at the active site pocket (39–42). According to these studies, the ba3-CO complex represents a highly-restricted site (γ form) (41), while the bo3-CO complex offers more open configurations of the dinuclear site (40). The iron-copper distances reported for the crystal structures of terminal oxidases concur with this view, with metal-metal distance ranging for 5.3 Å in bo3 and 4.4 Å in ba3 (31, 32, 43–46). However, metal-metal distance comparison from crystal structures should be used with caution since the structure of bo3 was only solved at 3.5 Å resolution, and because the redox state of the active sites during the X-ray diffraction data acquisition is not always clearly defined. This point is exemplified by a recent x-ray crystallographic study of a surface double mutant of cytochrome ba3 (E4Q & K258R) (47) which shows that the iron-copper distance can vary from 4.7 Å in the X-ray photoreduced oxidized crystal to 5.05 Å in chemically reduced crystals (48). However, the FTIR analysis of this double mutant of cytochrome ba3 in the -CO, -NO, and -NO complex in presence of CO gas produced identical results to that of wild type ba3 (Figures S4 and S5).

Based on our FTIR results, we hypothesize that in bo3-NO, a larger metal-metal distance prevents the efficient capture of the photolyzed NO by CuB. This hypothesis also explains the formation of a bo3-(NO)(CO) complex which is not observed in ba3. This [o3-NO • OC-CuB] state is evidenced by a differential signal centered at 2057 cm−1 from a CuB-carbonyl complex perturbed by the photolysis of NO from heme-o3. It is striking that one CO and one NO can co-exist at the dinuclear site of bo3, while two CO molecules cannot.(49) This observation suggests that the distance between heme o3 and CuB is just large enough to accommodate one CO at the CuB with one NO at the heme o3 in a bent geometry but not large enough to accommodate two linear diatomics. The limited accumulation of [o3-NO • OC-CuB]) to ~12% of the active sites may reflect the presence of multiple conformations of the heme-copper site (in bo3). The ν(N-O)o3 frequency in the [o3-NO • OC-CuB] state is equivalent to that observed in the [o3-NO • CuB] state. However, the [Fe-NO • OC-CuB] state exhibits only one ν(C-O)CuB at 2057 cm−1, which contrasts with the multiple ν(C-O)CuB bands observed at 2058 and 2073 cm−1 observed after photolysis of bo3-CO at low temperature (Figure S4) (50, 51). EXAFS measurements suggest that high ν(C-O)CuB frequencies could correspond to active site populations where one of the three coordinating histidines to CuB is weakly bound (52). Regardless of the structural significance of the different ν(C-O)CuB frequencies, the mixed-gas experiments suggest that the conformer that correspond to the high ν(C-O)CuB does not bind CO in presence of the heme o3-NO complex.

Reports of concomitant binding of two diatomic molecules at heme-copper dinuclear sites are scarce. In fully-reduced bovine and prokaryotic aa3, the loss or alteration of the EPR signal from a3-NO at high NO concentration has been assigned to the binding of a second NO molecule to CuB (35, 53). Using FTIR spectroscopy, Caughey and coworkers observed two ν(NO)s in bovine aa3: one at 1610 cm−1 assigned to a3-NO, and one at 1700 cm−1 assigned to CuB-NO (54). Presumably, the lack of NO reductase activity in aa3 terminal oxidases permits the accumulation of a stable [{FeNO}7 • {CuNO}11] complex, but the presence of two NO molecules in the active site of ba3 and bo3 is expected to represent a highly reactive intermediate within the NO reductase turnover. Although the characterization of a [o3-NO • OC-CuB] complex in bo3 suggests that this active site can also accommodate a [{FeNO}7 • {CuNO}11] trans-complex, this state may also correspond to a dead-end adduct as in the aa3 systems.

Low-temperature photolysis experiments are a sensitive probe of dinuclear heme-copper active site. The results presented here show that fully-reduced ba3 and bo3 bind a first NO molecule to the high-spin heme-iron(II) in similar fashion, but the distance of the CuB site relative to the heme iron differs significantly in the two proteins. In ba3, the close vicinity of the heme a3 and the CuB allows for the transfer of the photolyzed NO from the heme to CuB in a side-on geometry (17). In bo3, the larger metal-metal distance does not restrict the coordination of a second diatomic molecule at the CuB site (as long as it can adopt a bent geometry). Our experiments do not determine whether the CuB(I) site in bo3-NO binds a second NO molecule to form a trans [{FeNO}7/{CuNO}11] complex. Nevertheless, the comparison of ba3 and bo3 shows that the mechanism of NO reduction can accommodate the difference in heme-copper distances in these two active sites. This conclusion argues against the coordination of the second NO molecule to CuB(I) as an essential step in the reaction mechanism. Instead, the role of the CuB site may be limited to promote the formation of a heme iron-hyponitrite species through electrostatic interactions (11, 16).

Supplementary Material

FTIR spectra monitoring N2O production, EPR spectra of the bo3-NO complex, FTIR spectra of bo3-NO in different pH and salt concentration, and comparison of FTIR data for ba3 wild type and double mutant E4Q/K258R. This material is available free of charge via Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ninian Blackburn for the use of his Clark electrode, and Dr. James Whittaker for the use of his liquid helium cryostat.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Health (P.M.-L., GM74785; J.A.F., GM35342) and the Department of Energy (R.B.G., DE-FG02-87ER13716).

References

- 1.Lissenden S, Mohan S, Overton T, Regan T, Crooke H, Cardinale JA, Householder TC, Adams P, O’conner CD, Clark VL, Smith H, Cole JA. Identification of transcription activators that regulate gonococcal adaptation from aerobic to anaerobic or oxygen-limited growth. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:839–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Householder TC, Fozo EM, Cardinale JA, Clark VL. Gonococcal nitric oxide reductase is encoded by a single gene, norB, which is required for anaerobic growth and is induced by nitric oxide. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5241–5246. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5241-5246.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anjum MF, Stevanin TM, Read RC, Moir JW. Nitric oxide metabolism in Neisseria meningitidis. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:2987–2993. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.2987-2993.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castresana J, Lubben M, Saraste M, Higgins DG. Evolution of cytochrome oxidase, an enzyme older than atmospheric oxygen. EMBO J. 1994;13:2516–2525. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zumft WG, Braun C, Cuypers H. Nitric oxide reductase from Pseudomonas stutzeri. Primary structure and gene organization of a novel bacterial cytochrome bc complex. Eur J Biochem. 1994;219:481–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Oost J, de Boer AP, de Gier JW, Zumft WG, Stouthamer AH, van Spanning RJ. The heme-copper oxidase family consists of three distinct types of terminal oxidases and is related to nitric oxide reductase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heiss B, Frunzke K, Zumft WG. Formation of the N-N bond from nitric oxide by a membrane-bound cytochrome bc complex of nitrate-respiring (denitrifying) Pseudomonas stutzeri. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3288–3297. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3288-3297.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Averill BA. Dissimilatory nitrite and nitric oxide reductases. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2951–2965. doi: 10.1021/cr950056p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wasser IM, de Vries S, Moënne-Loccoz P, Schroder I, Karlin KD. Nitric oxide in biological denitrification: Fe/Cu metalloenzyme and metal complex NOx redox chemistry. Chem Rev. 2002;102:1201–1234. doi: 10.1021/cr0006627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zumft WG. Nitric oxide reductases of prokaryotes with emphasis on the respiratory, heme-copper oxidase type. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99:194–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moënne-Loccoz P. Spectroscopic characterization of heme iron-nitrosyl species and their role in NO reductase mechanisms in diiron proteins. Natl Prod Rep. 2007;24:610–620. doi: 10.1039/b604194a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giuffre A, Stubauer G, Sarti P, Brunori M, Zumft WG, Buse G, Soulimane T. The heme-copper oxidases of Thermus thermophilus catalyze the reduction of nitric oxide: evolutionary implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14718–14723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forte E, Urbani A, Saraste M, Sarti P, Brunori M, Giuffre A. The cytochrome cbb3 from Pseudomonas stutzeri displays nitric oxide reductase activity. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:6486–6491. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler C, Forte E, Maria Scandurra F, Arese M, Giuffre A, Greenwood C, Sarti P. Cytochrome bo3 from Escherichia coli: the binding and turnover of nitric oxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:1272–1278. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohta T, Kitagawa T, Varotsis C. Characterization of a bimetallic-bridging intermediate in the reduction of NO to N2O: a density functional theory study. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:3187–3190. doi: 10.1021/ic050991n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blomberg ML, Blomberg MRA, Siegbahn PEM. A theoretical study of nitric oxide reductase activity in a ba3-type heme-copper oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:31–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashi T, Lin IJ, Chen Y, Fee JA, Moënne-Loccoz P. Fourier transform infrared characterization of a CuB-nitrosyl complex in cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus: relevance to NO reductase activity in heme-copper terminal oxidases. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14952–14958. doi: 10.1021/ja074600a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pilet E, Nitschke W, Rappaport F, Soulimane T, Lambry JC, Liebl U, Vos MH. NO binding and dynamics in reduced heme-copper oxidases aa3 from Paracoccus denitrificans and ba3 from Thermus thermophilus. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14118–14127. doi: 10.1021/bi0488808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butler CS, Seward HE, Greenwood C, Thomson AJ. Fast cytochrome bo from Escherichia coli binds two molecules of nitric oxide at CuB. Biochemistry. 1997;36:16259–16266. doi: 10.1021/bi971481a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller LM, Pedraza AJ, Chance MR. Identification of conformational substates involved in nitric oxide binding to ferric and ferrous myoglobin through difference Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) Biochemistry. 1997;36:12199–12207. doi: 10.1021/bi962744o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, Hunsicker-Wang L, Pacoma RL, Luna E, Fee JA. A homologous expression system for obtaining engineered cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus HB8. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;40:299–318. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rumbley JN, Furlong Nickels E, Gennis RB. One-step purification of histidine-tagged cytochrome bo3 from Escherichia coli and demonstration that associated quinone is not required for the structural integrity of the oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1340:131–142. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(97)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao XJ, Sampath V, Caughey WS. Cytochrome c oxidase catalysis of the reduction of nitric oxide to nitrous oxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;212:1054–1060. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheesman MR, Watmough NJ, Pires CA, Turner R, Brittain T, Gennis RB, Greenwood C, Thomson AJ. Cytochrome bo from Escherichia coli: identification of haem ligands and reaction of the reduced enzyme with carbon monoxide. Biochem J. 1993;289:709–718. doi: 10.1042/bj2890709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yap LL, Samoilova RI, Gennis RB, Dikanov SA. Characterization of mutants that change the hydrogen bonding of the semiquinone radical at the QH site of the cytochrome bo3 from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8777–8775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611595200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yap LL, Samoilova RI, Gennis RB, Dikanov SA. Characterization of the exchangeable protons in the immediate vicinity of the semiquinone radical at the QH site of the cytochrome bo3 from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16879–16887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coyle CM, Vogel KM, Rush TS, 3rd, Kozlowski PM, Williams R, Spiro TG, Dou Y, Ikeda-Saito M, Olson JS, Zgierski MZ. FeNO structure in distal pocket mutants of myoglobin based on resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4896–4903. doi: 10.1021/bi026395b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibrahim M, Xu C, Spiro TG. Differential sensing of protein influences by NO and CO vibrations in heme adducts. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16834–16845. doi: 10.1021/ja064859d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu C, Spiro TG. Ambidentate H-bonding by heme-bound NO: structural and spectral effects of -O versus -N H-bonding. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008:613–621. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0349-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinakoulaki E, Ohta T, Soulimane T, Kitagawa T, Varotsis C. Detection of the His-heme Fe2+-NO species in the reduction of NO to N2O by ba3-oxidase from thermus thermophilus. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15161–15167. doi: 10.1021/ja0539490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soulimane T, Buse G, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, Huber R, Than ME. Structure and mechanism of the aberrant ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. EMBO J. 2000;19:1766–1776. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abramson J, Riistama S, Larsson G, Jasaitis A, Svensson-Ek M, Laakkonen L, Puustinen A, Iwata S, Wikstrom M. The structure of the ubiquinol oxidase from Escherichia coli and its ubiquinone binding site. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:910–917. doi: 10.1038/82824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blokzijl-Homan MF, van Gelder BF. Biochemical and biophysical studies on cytochrome aa3. 3 The EPR spectrum of NO-ferrocytochrome a3. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;234:493–498. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(71)90215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens TH, Brudvig GW, Bocian DF, Chan SI. Structure of cytochrome a3-Cua3 couple in cytochrome c oxidase as revealed by nitric oxide binding studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:3320–3324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.7.3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brudvig GW, Stevens TH, Chan SI. Reactions of nitric oxide with cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry. 1980;19:5275–5285. doi: 10.1021/bi00564a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mascarenhas R, Wei YH, Scholes CP, King TE. Interaction in cytochrome c oxidase between cytochrome a3 ligated with nitric oxide and cytochrome a. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:5348–5351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blackmore RS, Greenwood C, Gibson QH. Studies of the primary oxygen intermediate in the reaction of fully reduced cytochrome oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19245–19249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vos MH, Lipowski G, Lambry JC, Martin JL, Liebl U. Dynamics of nitric oxide in the active site of reduced cytochrome c oxidase aa3. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7806–7811. doi: 10.1021/bi010060x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alben JO, Moh PP, Fiamingo FG, Altschuld RA. Cytochrome oxidase a3 heme and copper observed by low-temperature Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of the CO complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:234–237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puustinen A, Bailey JA, Dyer RB, Mecklenburg SL, Wikstrom M, Woodruff WH. Fourier transform infrared evidence for connectivity between CuB and glutamic acid 286 in cytochrome bo3 from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13195–13200. doi: 10.1021/bi971091o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Einarsdottir O, Killough PM, Fee JA, Woodruff WH. An infrared study of the binding and photodissociation of carbon monoxide in cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2405–2408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Takahashi S, Hosler JP, Mitchell DM, Ferguson-Miller S, Gennis RB, Rousseau DL. Two conformations of the catalytic site in the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9819–9825. doi: 10.1021/bi00031a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwata S, Ostermeier C, Ludwig B, Michel H. Structure at 2.8 A resolution of cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Nature. 1995;376:660–669. doi: 10.1038/376660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshikawa S, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yamashita E, Inoue N, Yao M, Fei MJ, Libeu CP, Mizushima T, Yamaguchi H, Tomizaki T, Tsukihara T. Redox-coupled crystal structural changes in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Science. 1998;280:1723–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsukihara T, Aoyama H, Yamashita E, Tomizaki T, Yamaguchi H, Shinzawa I-K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yoshikawa S. The whole structure of the 13-subunit oxidized cytochrome c oxidase at 2.8 A. Science. 1996;272:1136–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunsicker-Wang LM, Pacoma RL, Chen Y, Fee JA, Stout CD. A novel cryoprotection scheme for enhancing the diffraction of crystals of recombinant cytochrome ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Acta Crystallogr. 2005;D61:340–343. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904033906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu B, Luna VM, Chen Y, Stout CD, Fee JA. An unexpected outcome of surface engineering an integral membrane protein: improved crystallization of cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus. Acta Crystallogr F. 2007;63:1029–1034. doi: 10.1107/S1744309107054176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu B, Chen Y, Doukov T, Soltis SM, Stout CD, Fee JA. Combined microspectrotometric and crystallographic examination of chemically-reduced and X-ray radiation-reduced forms of cytochrome ba3 oxidase from Thermus thermophilus: stucture of the reduced form of the enzyme. Biochemistry. 2008 doi: 10.1021/bi801759a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.We confirmed that the conditions used to accumulate a bo3-(NO)(CO) complex (1-atm CO, 25% glycerol, 30 K) do not allow for the formation of a bo3-(CO)2 complex in the absence of NO gas. Specifically, the low-temperature UV-vis and FTIR spectra show full complexation of the heme o3 by CO and complete transfer of CO from o3 to CuB upon illumination, with carbonyl stretching frequencies and intensities that are indistinguishable from those observed at low CO concentrations with 5% glycerol.

- 50.Hill J, Goswitz VC, Calhoun M, Garcia-Horsman JA, Lemieux L, Alben JO, Gennis RB. Demonstration by FTIR that the bo-type ubiquinol oxidase of Escherichia coli contains a heme-copper binuclear center similar to that in cytochrome c oxidase and that proper assembly of the binuclear center requires the cyoE gene product. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11435–11440. doi: 10.1021/bi00161a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Calhoun MW, Lemieux LJ, Thomas JW, Hill JJ, Goswitz VC, Alben JO, Gennis RB. Spectroscopic characterization of mutants supports the assignment of histidine-419 as the axial ligand of heme o in the binuclear center of the cytochrome bo ubiquinol oxidase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13254–13261. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ralle M, Verkhovskaya ML, Morgan JE, Verkhovsky MI, Wikstrom M, Blackburn NJ. Coordination of CuB in reduced and CO-liganded states of cytochrome bo3 from Escherichia coli. Is chloride ion a cofactor? Biochemistry. 1999;38:7185–7194. doi: 10.1021/bi982885l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pilet E, Nitschke W, Liebl U, Vos MH. Accommodation of NO in the active site of mammalian and bacterial cytochrome c oxidase aa3. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1767:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao XJ, Sampath V, Caughey WS. Infrared characterization of nitric oxide bonding to bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase and myoglobin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204:537–543. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FTIR spectra monitoring N2O production, EPR spectra of the bo3-NO complex, FTIR spectra of bo3-NO in different pH and salt concentration, and comparison of FTIR data for ba3 wild type and double mutant E4Q/K258R. This material is available free of charge via Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.