Abstract

As hamster scrapie cannot infect mice, due to sequence differences in their PrP proteins, we find “species barriers” to transmission of the [URE3] prion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae among Ure2 proteins of S. cerevisiae, paradoxus, bayanus, cariocanus, and mikatae on the basis of differences among their Ure2p prion domain sequences. The rapid variation of the N-terminal Ure2p prion domains results in protection against the detrimental effects of infection by a prion, just as the PrP residue 129 Met/Val polymorphism may have arisen to protect humans from the effects of cannibalism. Just as spread of bovine spongiform encephalopathy prion variant is less impaired by species barriers than is sheep scrapie, we find that some [URE3] prion variants are infectious to another yeast species while other variants (with the identical amino acid sequence) are not. The species barrier is thus prion variant dependent as in mammals. [URE3] prion variant characteristics are maintained even on passage through the Ure2p of another species. Ure2p of Saccharomyces castelli has an N-terminal Q/N-rich “prion domain” but does not form prions (in S. cerevisiae) and is not infected with [URE3] from Ure2p of other Saccharomyces. This implies that conservation of its prion domain is not for the purpose of forming prions. Indeed the Ure2p prion domain has been shown to be important, though not essential, for the nitrogen catabolism regulatory role of the protein.

STUDIES of the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) gave rise to the concept of a “prion” meaning an “infectious protein,” without the need for an accompanying nucleic acid to transmit the corresponding disease state (Griffith 1967; Prusiner 1982). The PrP protein, product of the Sinc gene, is believed to be the protein whose amyloid form is infectious (Dickinson et al. 1968; Bolton et al. 1982; Caughey and Baron 2006; Aguzzi et al. 2008). Infection of sheep TSE (scrapie) to goats requires a longer incubation than from sheep to sheep or from goat to goat (Cuille and Chelle 1939), a phenomenon found to be general and now called the “species barrier” (Collinge and Clarke 2007). The species barrier is largely due to sequence differences in the PrP protein (Prusiner et al. 1990).

Different scrapie isolates can have clearly distinct incubation times, disease symptoms, and distribution of brain lesions in a single mouse line. This phenomenon, called prion “strains” or “variants,” implies differences in the infectious agent, and the finding of differences between prion strains in the protease-resistant part of PrP supported PrP's role as the infectious agent (Bessen and Marsh 1992). The properties of a prion variant are (with some exceptions) maintained even though the prion is passed through different species with significantly different PrP sequences (Bruce et al. 1994).

The species barrier and prion strain/variant phenomena are connected in that the extent of the species barrier depends critically on the prion strain. Most dramatically, although centuries of human exposure to sheep scrapie has not produced detectable infection, the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) epidemic led to >200 cases of a variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD). That this difference is due to prion variant differences is shown by studies with transgenic mice (reviewed in Collinge and Clarke 2007).

Saccharomyces cerevisiae prions include [URE3], [PSI+], [PIN+], [SWI+], and [β], which are prions of Ure2p, Sup35p, Rnq1p, Swi1p, and Prb1p, respectively (Wickner 1994; Derkatch et al. 2001; Roberts and Wickner 2003; Du et al. 2008). Ure2p is a regulator of nitrogen catabolism, repressing the genes encoding enzymes and transporters needed for the utilization of poor nitrogen sources (e.g., allantoate) specifically when a good nitrogen source (e.g., ammonia) is available (Cooper 2002). Dal5p is the allantoate transporter and ureidosuccinate (USA), the product of aspartate transcarbamylase (Ura2p), is structurally similar to allantoate (Turoscy and Cooper 1987). The presence of the [URE3] prion is thus assayed by the uptake by the Ure2-controlled Dal5p transporter of USA or by activity of ADE2 driven by the DAL5 promoter (Lacroute 1971; Schlumpberger et al. 2001).

The [URE3], [PSI+], and [PIN+] prions are based on self-propagating amyloids of their respective proteins (King and Diaz-Avalos 2004; Tanaka et al. 2004; Brachmann et al. 2005; Patel and Liebman 2007; reviewed in Wickner et al. 2008b). Species barriers have been described for [PSI+] (Chernoff et al. 2000; Kushnirov et al. 2000; Santoso et al. 2000; Chen et al. 2007) and [URE3] (Edskes and Wickner 2002; Baudin-Baillieu et al. 2003) and prion variants have been recognized in yeast prions [PSI+], [URE3], and [PIN+] (Derkatch et al. 1996; Schlumpberger et al. 2001; Bradley et al. 2002; Brachmann et al. 2005). The [URE3], [PSI+], and [PIN+] prion amyloids are each parallel in-register β-sheet structures (Shewmaker et al. 2006; Baxa et al. 2007; Wickner et al. 2008a), and different prion variants of [PSI+] differ at least in the extent of the β-sheet structure (Toyama et al. 2007; Chang et al. 2008).

Here we examine Ure2 proteins in the genus Saccharomyces, finding that one does not form prions, that there are species barriers between different Ure2 proteins, and that the extent of the species barrier depends on the individual prion variant (presumably amyloid structure) that is being transmitted. Moreover, prion variant properties can be maintained through passage in a prion protein of a different species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media:

Rich medium (YPAD, yeast extract peptone adenine dextrose), minimal medium (SD, synthetic dextrose), glycerol-rich medium (YPG, yeast extract peptone glycerol), and sporulation medium were prepared as described by Sherman (1991). YES medium is 0.5% yeast extract, 3% glucose, 30 mg/liter tryptophan.

Strains:

YHE256 is MATa kar1 ura2 arg- [URE3cer3687]cer (Edskes and Wickner 2000). LM9 (MATα ura2 leu2∷hisG his3∷hisG ure2∷kanMX PDAL5ADE2 PDAL5CAN1) was constructed in the Σ1278b background (a) integrating CAN1 with the DAL5 promoter amplified from strain BY108 (Brachmann et al. 2005) selected for canavanine resistance using ammonia as a nitrogen source, (b) replacing 500 bp usptream of the ADE2 ORF with 561 bp of sequence upstream of the DAL5 ORF using strain BY241 (Brachmann et al. 2005) as described (Schlumpberger et al. 2001), and (c) replacing the URE2 ORF with the kanMX4 cassette with a PCR fragment obtained using a ure2∷kanMX4 strain from the Saccharomyces Genome Deletion Project.

Transformation of LM9 with DNA fragments containing the URE2 ORFs from several Saccahromyces species flanked by upstream and downstream seqeuences of S. cerevisiae URE2 resulted in strains: LM11 (S. bayanus URE2), LM16 (S. mikatae URE2), LM18 (S. paradoxus URE2-TGA), LM27 (S. castellii URE2), LM41 (S. cariocanus URE2), and LM45 (S. cerevisiae URE2). Transformants were selected through their resistance to canavanine. Those that had become G418 sensitive were checked for acquisition of the corresponding URE2 gene by PCR amplification from genomic DNA and sequencing. A tentative tree of Ure2p sequences is shown in supplemental Figure 3.

YHE1254 containing URE2 from S. paradoxus terminating with a TAA codon was created using URE2 tagged with a 3′-located HIS3 gene flanked by loxP sites as a marker. HIS3 was removed by expression of CRE from plasmid YEp351-cre-cyh (Delneri et al. 2000).

Adding kar1, trp1, and changing mating type in LM9-derived strains:

Kar1Δ15 (Vallen et al. 1992) containing a deletion in the ORF between bp 106 and 192 was amplified by PCR from strain L2598 (gift from S. Liebman). The PCR product started 80 bp upstream of the KAR1 start codon and terminated 30 pb downstream of its stop codon. The hygromycin-resistance expression cassette from pAG32 (Goldstein and McCusker 1999) was amplified by PCR using primers containing KAR1 sequences downstream of the stop codon (5′ primer nt 11–30 and 3′ primer nt 37–57). Fusion PCR created a fragment containing kar1Δ15-hygromycin-KAR1 (nt 57–347 downstream of the stop codon). Transformants were selected through their resistance to hygromycin.

The mating type was switched by expressing HO from pJH132 (Jensen and Herskowitz 1984) upon galactose induction.

Strains were made tryptophan prototrophs and histidine auxotrophs by replacing the TRP1 ORF with the HIS3 ORF from pRS423 (Christianson et al. 1992). The resulting strains have the genotype MATa ura2 leu2∷hisG his3∷hisG trp1∷HIS3 PDAL5ADE2 PDAL5CAN1 kar1∷kar1Δ15-hphMX4 URE2*. URE2* represents URE2 from the different Saccharomyces species with LM105 containing S. cerevisiae URE2, LM107 containing S. mikatae URE2, LM108 containing S. cariocanus URE2, LM117 containing S. paradoxus URE2 terminating with a TGA stop codon, LM194 containing S. bayanus URE2, and LM191 containing S. castellii URE2.

Strains containing S. castellii URE2:

LM191 (see above) forms white colonies on YES medium. Several attempts to remake LM191 always resulted in strains that formed white colonies on YES plates. LM191 and LM27 (see above) were crossed and sporulation of the diploids resulted in irregular segregation of red and white spore clones. Mating and sporulation of two red spore clones resulted in tetrads giving ∼100% red spore clones. One of these, YHE1242 (MATα ura2 leu2∷hisG his3∷hisG URE2castellii PDAL5ADE2 PDAL5CAN1 kar1∷kar1Δ15-hphMX4) was used for [URE3] induction experiments. Upon propagation, most URE2 castellii cells become light red and easily revert further to an Ade+ phenotype. Growth on medium containing 3 mm guanidine does not restore the red/Ade− phenotype. These cells remain clearly USA− throughout.

LM51 (MATα ura2 leu2 trp1 kar1 ure2∷kanMX4 PDAL5CAN1 PDAL5ADE2) was a meiotic segregant of LM9 × BY304 (gift from A. Brachmann). The URE2 gene from S. cerevisiae was introduced into LM51 as described above resulting in strain LM60 (MATα ura2 leu2 trp1 PDAL5CAN1 PDAL5ADE2 kar1).

Plasmid construction:

pTIF2 was created starting from pH125 (2μ LEU2 PADH1-TADH1)(Edskes and Wickner 2000). The NheI–BamHI bordered ADH1 promoter was replaced by the 179 bp URE2cerevisiae 5′-UTR creating pH795. Next the XhoI–BglII bordered ADH1 terminator was replaced with the 400 bp URE2cerevisiae 3′-UTR creating pH795. Finally the NsiI–BbeI fragment of pH795 containing most of the 2μ origin of replication and LEU2 was replaced with a StuI site.

URE2 was amplified by PCR from yeast strains S. cariocanus 50791, S. castellii NRRL Y-12630, and S. mikatae 1815 (gifts from Jim Dover, wustl) using primers based on the sequences obtained by Cliften et al. (2001). Yeast cells were heated to 95° for 3 min in 0.25% SDS and the cleared lysate was used for PCR. Cloning of URE2 from S. cerevisiae, S. bayanus (YJM562), and S. paradoxus (YJM498) has been described (Edskes and Wickner 2002). All URE2 sequences contained a BamHI site upstream of the start codon and a XhoI site downstream of the stop codon. PCR products were cloned into the BamHI/XhoI window of pH317 [2μ replicon LEU2 PGAL1 (Edskes and Wickner 2000), creating pH376 (S. cerevisiae URE2) (Bradley et al. 2002)], pLM100 (S. bayanus URE2), pLM99 (S. paradoxus URE2), pLM96 (S. cariocanus URE2), and pLM98 (S. mikatae URE2). These same PCR products were also cloned into pTIF2 (PURE2cerevisiae-TURE2cerevisiae) creating pTIF5 (S. cerevisiae URE2), pLM93 (S. bayanus URE2), pLM92 (S. paradoxus URE2), pLM89 (S. cariocanus URE2), and pLM91 (S. mikatae URE2).

The URE2 ORF present in pLM99 and pLM92 terminates with a TGA stop codon. However, the native S. paradoxus URE2 stop codon is TAA. Cloning of a PCR amplified S. paradoxus URE2 containing a TAA-A stop sequence into the BamHI/XhoI window of pH317 created pH1010. This same S. paradoxus URE2 containing the TAA-A sequence was cloned into the BamHI/XhoI window of pTIF2 creating pH1001. HIS3 was amplified by PCR from pRS423 (nt 201–1163) using oligos containing loxP sites (5′-ATAACTTCGTATAGCATACATTATACGAAGTTAT-3′). LoxP-bordered HIS3 was ligated as a XhoI fragment into the XhoI site of pH1001 creating pH1002.

We used homologous recombination cloning in yeast to make a 2μ DNA LEU2- based plasmid overexpressing the S. castellii URE2 using a GAL1 promoter. A 632-bp GAL1 promoter fragment and a 316-bp ADH1 terminator fragment, identical to those present in pH317, were fused by PCR to the S. castelli URE2 ORF. This PCR product together with BamHI/XhoI-digested pH 317 was transformed into yeast.

pH327 (Edskes et al. 1999) expresses S. cerevisiae URE2 fused to GFP from a centromeric LEU2-containing plasmid using a URE2 promoter. The unique NdeI site was removed by changing it from CATATG into CACATG using the QuickChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) creating pLM147. The URE2 ORFs from S. cerevisiae, S. paradoxus, S. bayanus, S. cariocanus, and S. mikatae all contain a unique NdeI site 45 bp before the stop codon. In this region all five Ure2 proteins have identical amino acid sequences. Replacement of the URE2-containing BamHI/NdeI fragment from pLM147 with similar fragments from pLM99 (S. paradoxus), pLM100 (S. bayanus), pLM96 (S. cariocanus), and pLM98 (S. mikatae) created, respectively, pLM152, pLM153, pLM150, and pLM151.

RESULTS

Divergence of URE2 sequences of Saccharomyces species:

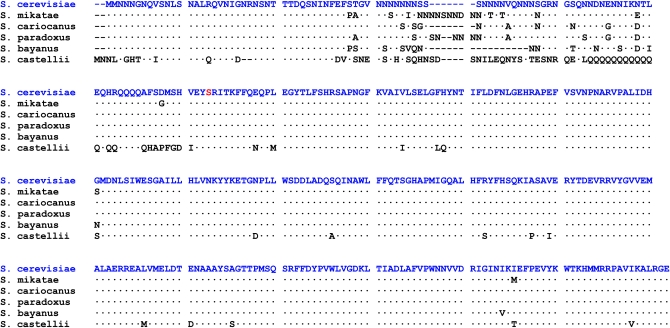

The genus Saccharomyces includes a number of species that are significantly diverged but that nonetheless can mate with each other (Sipiczki 2008). The Ure2 protein sequences of S. cerevisiae, mikatae, cariocanus, paradoxus, bayanus, and castelli are shown in Figure 1. As previously noted for a wider range of yeasts (Edskes and Wickner 2002), the N-terminal ∼40 residues are largely conserved, but there are a number of differences in the following ∼50 residues of the prion domain, and the C-terminal parts of the molecule are nearly invariant.

Figure 1.—

Ure2 protein sequences of Saccharomyces species. “−” means a residue deletion and “·” means a residue identical to the S. cerevisiae sequence.

The URE2 open reading frames of S. cerevisiae, mikatae, cariocanus, paradoxus, bayanus, and castellii were used to replace the kanMX cassette at the URE2 locus in cerevisiae strain LM9 (MATα ura2 leu2 his3 ure2∷kanMX) (see materials and methods).

Nomenclature:

We indicate a [URE3] prion variant originating in cerevisiae and propagating in cells expressing the Ure2p of mikatae by the symbol [URE3cer]mik. A prion isolate (variant) number can be added, e.g.,[URE3cer4]mik.

Prion formation by Ure2p of Saccharomyces species in cerevisiae:

To determine if the different Ure2 proteins could form [URE3], the homologous Ure2p or the cerevisiae Ure2p was overexpressed from a GAL1 promoter on a plasmid and prion formation was detected on USA or −Ade plates containing dextrose (Table 1). The chromosomal URE2 from each species was driven by the constitutive cerevisiae URE2 promoter. The cerevisiae, mikatae, cariocanus, paradoxus, and bayanus Ure2p's could each form [URE3], and, as expected, the frequency with which [URE3] arose was greater when the overexpressed Ure2p was the same as that encoded on the chromosome.

TABLE 1.

Induction of prion formation in S. cerevisiae strains (MATα ura2 leu2∷hisG his3∷hisG PDAL5CAN1 PDAL5ADE2 [ure-o]) with chromosomal URE2 from various Saccharomyces species

| Overexpress

|

Overexpress

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of URE2 (strain) | Vector | cerevisiae | Homol. | Vector | cerevisiae | Homol. |

| USA+/106 cells | ADE+/106 cells | |||||

| cerevisiae (LM45) | 3 | 27,000 | 27,000 | 10 | 357,500 | 357,000 |

| mikatae (LM16) | 6 | 2,675 | 14,200 | 28 | 1,200 | 74,500 |

| cariocanus (LM41) | 4 | 4,175 | 6,050 | 11 | 5,825 | 86,750 |

| paradoxus (LM18) TGAC.. | 15 | 3,775 | 12,800 | 4 | 5,050 | 8067 |

| bayanus (LM11) | 6 | 325 | 5,600 | 4 | 341 | 8,400 |

| castellii | 4 | 5 | 0 | ND | ND | |

Ure2p of S. cerevisiae or of the same Ure2p as encoded on the chromosome (homol.) was transiently overproduced from a plasmid with a GAL1 promoter. Numbers are averages of four independently assayed transformants (except for castellii where pooled red/Ade minus clones were used in two independent assays). ND, not done.

Except for URE2paradoxus, each of the URE2s used here had its native stop codon: cerevisiae had TGA, bayanus TAA, castellii TAG, cariocanus TGA, and mikatae TAA. URE2paradoxus with a TGA stop codon, allows some readthrough (Talarek et al. 2005), and so we also constructed URE2paradoxus with a TAA stop sequence, the same as in the native URE2paradoxus gene. In this case as well, we observed that overexpression of the protein induced the high frequency de novo appearance of the prion (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

The ability to induce [URE3] upon overexpression of Ure2p was compared in strains LM18 (URE2paradoxusTGA) and YHE1254 (URE2paradoxusTAAA), each having genotype MATα ura2 leu2∷hisG his3∷hisG PDAL5CAN1 PDAL5ADE2 [ure-o]

| Strain | Plasmid | USA+/106 | Ade+/106 |

|---|---|---|---|

| URE2paradoxusTGA | Vector | 14 | 19 |

| URE2paradoxusTGA | PGAL1URE2parTGA | 1,230 | 110,300 |

| URE2paradoxusTGA | PGAL1URE2parTAAA | 1,630 | 104,300 |

| URE2paradoxusTAAA | Vector | 119 | 76 |

| URE2paradoxusTAAA | PGAL1URE2parTGA | 4,870 | 67,500 |

| URE2paradoxusTAAA | PGAL1URE2parTAAA | 3,800 | 49,300 |

Plasmids were: vector, pH317 = 2μ DNA - LEU2 - PGAL1; PGAL1URE2paradoxusTGA, pLM99 = 2μ DNA - LEU2 - PGAL1 URE2paradoxusTGA; PGAL1URE2parTAAA, pH1010 = 2μ DNA - LEU2 PGAL1 URE2paradoxusTAAA.

S. castellii Ure2p does not form a prion:

Because the castellii URE2 gene was toxic to Escherichia coli, all constructs were made using PCR directly in yeast (see materials and methods). Moreover, the Ade− phenotype was somewhat leaky and not useful so all experiments were done using USA uptake to indicate Ure2p activity. Overexpression of Ure2castellii did not induce the appearance of USA+ colonies (Table 1). Cytoduction of [URE3] from several [URE3cer]cer, into cells expressing Ure2castellii produced only a few USA+ clones among >250 cytoductants. Each of these was further tested for cytoduction into another Ure2castellii strain and none transferred the USA+ phenotype to cytoductants. A meiotic cross of YHE1236 (Ure2castellii) and YHE1233 ([URE3cer109]cer) produced uniform 2 USA+:2USA− segregation in each of 24 four-spored tetrads. In each of the 12 tetrads checked by PCR with primers specific for the castellii and cerevisiae URE2 genes, the USA+ segregants all had the cerevisiae gene and the USA− segregants all had the castellii gene. Thus, cerevisiae cells with Ure2castellii do not develop their own [URE3] at a detectable frequency, nor can they be infected with [URE3cer]cer, the best one at crossing species barriers (see next section).

Species barriers among Saccharomyces [URE3]s:

A single [URE3] variant derived by over expression of each Ure2p was used as cytoduction donor to [ure-o] strains of opposite mating type carrying each of the URE2 genes (Table 3). In each case the transmission was best when the URE2 of the donor (and origin of the [URE3] isolate) was the same as the URE2 of the recipient. Most cases in which the donor and recipient had different URE2s resulted in lower transmission frequency—a species barrier.

TABLE 3.

Species barriers among Ure2p's of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, mikatae, cariocanus, paradoxus, and bayanus

| Recipient

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cerevisiae | mikatae | cariocanus | paradoxus | bayanus | ||

| Donor | Strain | LM105 | LM107 | LM108 | LM117 | LM194 |

| %USA+/%ADE+ | ||||||

| [URE3cer]cer | LM109 | 100/98 | 98/93 | 98/96 | 97/97 | 84/88 |

| [URE3mik]mik | LM112 | 44/52 | 100/97 | 7/9 | 11/3 | 47/94 |

| [URE3car]car | LM150 | 59/75 | 21/38 | 60/71 | 75/80 | 12/33 |

| [URE3par]par | LM156 | 17/38 | 8/34 | 63/77 | 75/80 | 2/10 |

| [URE3bay]bay | LM121 | 0/0 | 6/6 | 0/0 | 2/0 | 100/100 |

Donors and recipients are all isogenic S. cerevisiae. From 44 to 107 cytoductants were scored and % USA+ and % ADE+ are shown. The cariocanus and paradoxus donors were >98% mitotically stable. Donor genotypes: MATα ura2 leu2∷hisG his3∷hisG PDAL5CAN1 PDAL5ADE2. Recipient genotypes: MATa ura2 leu2∷hisG his3∷hisG trp1∷HIS3 kar1Δ15-hphMX4 PDAL5CAN1 PDAL5ADE2.

[URE3cer109]cer (i.e., the [URE3] in strain LM109 generated from the cerevisiae Ure2p and in a strain whose Ure2p is from cerevisiae) was efficiently transmitted to each of the other species' Ure2p (Table 3). In many cases, having crossed the species barrier, a prion is less stable than with its Ure2p of origin. For example, although [URE3cer3687]cer propagates with Ure2ps of five other species, it is more unstable in those strains than with Ure2cerevisiae (data not shown). We also compared ability of Ure2paradoxus terminated with TGA and TAA to be a recipient of [URE3cer3687]cer and found them similar (supplemental Table 1).

Species barriers are not symmetrical (Table 3). For example, [URE3cer109]cer efficiently infects Ure2bayanus, but [URE3bay121]bay does not infect Ure2cerevisiae at all. However, these results are very much dependent on which variant of each is considered.

[URE3cer] maintains ability to propagate on Ure2pcer in hosts with other Ure2ps:

[URE3cer3687]cer (Wickner 1994) was cytoduced into cells expressing bayanus, mikatae, paradoxus, or cariocanus Ure2p, and stable [URE3cer3687]xyz derivatives of each were obtained. These were grown several times to single colonies and then cytoduced back into LM60 (MATa leu2 trp1 kar1 URE2cerevisiae PDAL5ADE2 PDAL5CAN1 [ure-o]) (Table 4). Although transmission of [URE3]s native to other species' Ure2s are often poorly transmitted to Ure2cerevisiae (Table 3), transmission of this [URE3cer3687] (originating in cerevisiae) from each of the other species to Ure2cerevisiae was quite efficient (Table 4). This indicates that the strain characteristics of [URE3cer3687] were maintained during passage in cells expressing only the Ure2p of another species.

TABLE 4.

Prion variant characteristics are maintained on passage through another species

| Donor

|

Recipient

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [URE3] | Strain | Species strain | Cytoductants | USA+ | ADE+ |

| [URE3cer3687]cer | LM69 | cerevisiae LM60 | 115 | 114 | 114 |

| [URE3cer3687]bay | LM29 | 127 | 106 | 111 | |

| [URE3cer3687]mik | LM34 | 45 | 44 | 44 | |

| [URE3cer3687]par | LM36 | 83 | 82 | 71 | |

| [URE3cer3687]car | LM68 | 82 | 73 | 76 | |

[URE3cer3687]cer was cytoduced into strains expressing each of the indicated Ure2s, and then, after extensive growth on YES plates, cytoduced into LM60 expressing the cerevisiae Ure2p. Donor genotypes: MATα ura2 leu2∷hisG his3∷hisG PDAL5CAN1 PDAL5ADE2. Recipient genotypes: MATa ura2 leu2 trp1 kar1 PDAL5CAN1 PDAL5ADE2.

Species barriers vary with [URE3] prion variant:

We examined the ability of several [URE3car]car isolates to be transmitted to Ure2mikatae (Table 5). As with transmission of [URE3cer3687]cer to Ure2mikatae, [URE3cer3687]car was transmitted well to Ure2mikatae. While [URE3car146]car and [URE3car147]car were likewise transmitted as well to Ure2mikatae as they were to Ure2cariocanus, [URE3car145]car and [URE3car151]car were well transmitted to Ure2cariocanus, but only poorly to Ure2mikatae (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Prion variants of the same molecule may differ in their degree of species barrier

| Recipients

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| USA+/total cytoductants

| |||

| Donor | Strain | cariocanus | mikatae |

| [ure-o]car | LM41 | 0/48 | 0/47 |

| [URE3cer3687]car | LM68 | 39/43 | 32/36 |

| [URE3car145]car | LM145 | 43/48 | 2/47 |

| [URE3car151]car | LM151 | 43/48 | 3/45 |

| [URE3car146]car | LM146 | 28/45 | 26/42 |

| [URE3car147]car | LM147 | 22/40 | 32/44 |

One [URE3cer]car and four independent [URE3car] car variants were each cytoduced into strains expressing either the Ure2pcariocanus or Ure2pmikatae, and cytoductants were scored for USA uptake. Donor genotypes: MATα ura2 leu2∷hisG his3∷hisG PDAL5CAN1 PDAL5ADE2. Recipients LM108 with URE2cariocanus and LM107 with URE2mikatae have genotype MATa ura2 leu2∷hisG his3∷hisG trp1∷HIS3 kar1Δ15-hphMX4 PDAL5CAN1 PDAL5ADE2.

Dependence of species barrier on prion variant can also be seen in a contrast of strains whose [URE3] arose from the same Ure2p compared with prions arising from the Ure2p of another species. For example, each of six [URE3mik]mik transmitted poorly to cells expressing Ure2cariocanus, but [URE3cer3687]mik transmitted readily to the same cells (supplemental Table 2), as does [URE3cer109]cer (Table 3). Similarly, each of three [URE3bay]bay isolates transmit poorly to each other species, but a [URE3cer3687]bay transmits well to all (supplemental Table 3). Thus, the species barrier depends on the particular prion variant, and, as before, the species range is preserved with transmission through another species.

Species barrier does not mean absence of interaction:

All [URE3bay]bay prions tested are poorly transmitted to any of the other Ure2s (supplemental Table 3). However, we find that expression of each of the other Ure2s as Ure2–GFP fusion proteins interferes with propagation of [URE3bay121]bay, curing it quite efficiently (supplemental Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Usa and Ade phenotypes are not always parallel:

The Ure2 proteins from other Saccharomyces species generally function in cerevisiae, but not uniformly so. For example, the castellii Ure2p does not completely repress the PDAL5ADE2 gene. Repression of USA uptake apparently requires less active Ure2p than does repression of ADE2 in the PDAL5ADE2 gene. This may reflect either differences in the turnover numbers of Dal5p and of Ade2p or that Ure2p regulates both transcription and protein maturation of Dal5p, but only transcription of the PDAL5ADE2 gene. Although the C-terminal glutathione-S-transferase-like domains of Ure2p are highly conserved among the Saccharomyces species, Gln3p, with which it interacts, is poorly conserved. The cerevisiae Ure2p is in ∼20-fold excess over Gln3p (supplemental Figure S1) and is a dimer evenly distributed in the cytoplasm in [ure-o] cells, whereas Gln3p is present in a large complex (supplemental Figure S2) and appears in localized sites in the cell (Tate and Cooper 2007). Thus, the relation of [URE3] variants to their phenotypes is certainly not simple and is not yet understood.

Why do URE2 prion domain-encoding sequences vary so rapidly?

The Ure2p prion domain is important for the nitrogen regulation function of the molecule, protecting it from degradation and facilitating interaction with other proteins related to nitrogen regulation (Shewmaker et al. 2007). The part of the prion domain that performs this function has not been determined, but it is possible that the 40–90 region is simply under no functional constraint and so varies rapidly. Both parts of the prion domain are unstructured (Pierce et al. 2005), indicating that maintaining a stable protein fold does not determine the difference between the relatively conserved region (1–40) and the rapidly varying region (40–90).

Alternatively, the variation may be selected for to acquire the species barrier that we observe. John Collinge has suggested that the human PrP M/V polymorphism at residue 129 may have been selected because heterozygotes are immune to infectious CJD in an era when cannibalism was more common than it is now (Mead et al. 2003). Similarly, [URE3] is a substantial detriment to its host (Nakayashiki et al. 2005) and the rapid variation in the 40–90 region of the prion domain may be a consequence of selection for immunity to the [URE3] infectious disease.

Why is there a conserved region?

The conservation of sequence in the 1–40 region might be interpreted as important for prion formation if the [URE3] prion were not known to be detrimental. However, beyond this, it has been shown that sequence of the Ure2p prion domain is of minimal importance for prion formation and that only amino acid composition is important (Ross et al. 2004), so prion formation cannot explain the conservation of sequence. It is likely that the conserved region is important for its role in facilitating nitrogen regulation (Shewmaker et al. 2007).

Prion domains that cannot be a prion:

We find that the Ure2p of S. castellii will not form [URE3] itself, nor can it be infected with [URE3] from S. cerevisiae. This suggests that the Ure2p prion domain is not conserved in this organism for the purpose of prion formation, but it remains possible that the S. castellii Ure2p can form a prion in S. castellii. Although we had observed [URE3] formation by the S. paradoxus Ure2p (Edskes and Wickner 2002), it was reported that this was a result of our construct having a TGA termination codon resulting in significant readthrough (Talarek et al. 2005). Moreover, it was found that the S. paradoxus Ure2p (identical in sequence to what we used) could not become a prion in either cerevisiae (Baudin-Baillieu et al. 2003) or paradoxus itself (Talarek et al. 2005). We have constructed a strain with the TAA termination codon and find that in cerevisiae it can be infected with [URE3] from the cerevisiae Ure2p. The discrepancy between these results may be the result of some other strain background difference.

Species barriers among Saccharomyces Ure2 proteins:

For each pair of species forming [URE3] prions, there is some degree of incompatibility. Generally the cerevisiae [URE3] isolates showed the smallest species barriers. Whether this is a result of the experiments having been carried out in S. cerevisiae or is an inherent feature of the sequences is not yet clear. The differences in amino acid sequence among the Ure2 prion domains of Saccharomyces species are comparable to that among the PrP proteins of different mammals. Collinge has proposed that each sequence has a range of conformations that it can assume in the prion polymers, and that the height of the species barrier is generally inversely proportional to the overlap of the conformational ranges of the two sequences (Collinge 1999; Collinge and Clarke 2007). This model doubtless applies to Saccharomyces prions as well as it does to those of mammals.

But how does a minor difference in amino acid sequence result in a substantial species barrier in spite of the fact that randomizing the sequence does not prevent prion formation (Ross et al. 2004, 2005a)? We proposed that only a parallel in-register β-sheet structure can explain this finding (Ross et al. 2005b), and indeed infectious amyloids of the prion domains of Ure2p, Sup35p, and Rnq1p have this architecture (Shewmaker et al. 2006; Baxa et al. 2007; Wickner et al. 2008a). This structure is stabilized by “polar-zipper” H-bonds between aligned glutamine and asparagine side chains (Perutz et al. 1994; Chan et al. 2005; Nelson et al. 2005) and hydrophobic interactions, both of which would be decreased by having a mixture of sequences. This structure can also be viewed as a linear crystal, and, like a 3D crystal, the introduction of a nonidentical molecule is expected to disrupt the structure beyond its actual location.

Species barriers vary with prion variants:

Unlike sheep scrapie, the BSE epidemic spread to humans and other animals. This was not only a consequence of the sequence of bovine PrP, but of the conformation of the BSE prion variant (reviewed in Collinge and Clarke 2007). We observe a clear dependence of species barrier on prion variant. For example, the [URE3cer3687]bay is well transmitted to all Ure2 sequences, but four other bayanus [URE3]s strongly prefer Ure2bayanus. Applying the Collinge model, one would say that, unlike the others, [URE3 cer3687]bay is a conformation easily adopted by the other Ure2ps.

In yeast prions, variants have been defined by strength of the prion phenotype, stability of the prion, and the effects of various chaperones (e.g., Derkatch et al. 1996; Borchsenius et al. 2006; Kryndushkin and Wickner 2007). As shown here for yeast, and long known in mammalian systems, the host range can also serve as a means to distinguish different prion variants. Since two variants based on different structures could easily have the same phenotype intensity and stability, it is important to have as many distinguishing characteristics as possible.

[Het-s] has only one variant because it is adaptive:

Only one variant of the [Het-s] prion has been described (Benkemoun and Saupe 2006), and the very sharp lines seen in 2D solid-state NMR studies of amyloid of HETs218–289 (the prion domain) (Ritter et al. 2005) indicate that it adopts a very specific single conformation, while the multiple variants (Derkatch et al. 1996; Bradley et al. 2002; Brachmann et al. 2005) and wider 2D solid-state NMR peaks for the prion domains of Ure2p, Sup35p, and Rnq1p (Shewmaker et al. 2006; Baxa et al. 2007; Wickner et al. 2008a) indicate that they spontaneously form a mixture of distinct amyloid structures. This may reflect the fact that [Het-s] carries out a function—either the host function, heterokaryon incompatibility, or the “spore-killer” meiotic drive function. In contrast, [URE3] and [PSI+] are diseases of yeast in which the amyloids do not have an evolved structure–function relationship (Nakayashiki et al. 2005). A knee bends in a very specific way, but a leg may be broken in many ways.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tiffany Weinkopff for the construction of pTIF2 and pTIF5, and Jim Dover of Washington University for the gift of Saccharomyces strains. We are grateful to Anthony Furano for protein sequence analysis. This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

References

- Aguzzi, A., F. Baumann and J. Bremer, 2008. The prion's elusive reason for being. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 31 439–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin-Baillieu, A., E. Fernandez-Bellot, F. Reine, E. Coissac and C. Cullin, 2003. Conservation of the prion properties of Ure2p through evolution. Mol. Biol. Cell 14 3449–3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxa, U., R. B. Wickner, A. C. Steven, D. Anderson, L. Marekov et al., 2007. Characterization of β-sheet structure in Ure2p1–89 yeast prion fibrils by solid state nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry 46 13149–13162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkemoun, L., and S. J. Saupe, 2006. Prion proteins as genetic material in fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 43 789–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessen, R. A., and R. F. Marsh, 1992. Biochemical and physical properties of the prion protein from two strains of the transmissible mink encephalopathy agent. J. Virol. 66 2096–2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, D. C., M. P. McKinley and S. B. Prusiner, 1982. Identification of a protein that purifies with the scrapie prion. Science 218 1309–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchsenius, A. S., S. Muller, G. P. Newnam, S. G. Inge-Vechtomov and Y. O. Chernoff, 2006. Prion variant maintained only at high levels of the Hsp104 disaggregase. Curr. Genet. 49 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann, A., U. Baxa and R. B. Wickner, 2005. Prion generation in vitro: amyloid of Ure2p is infectious. EMBO J. 24 3082–3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, M. E., H. K. Edskes, J. Y. Hong, R. B. Wickner and S. W. Liebman, 2002. Interactions among prions and prion “strains” in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99(Suppl. 4): 16392–16399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, M. E., A. Chree, I. McConnell, J. Foster, G. Pearson et al., 1994. Transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy and scrapie to mice: strain variation and the species barrier. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 343 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughey, B., and G. S. Baron, 2006. Prions and their partners in crime. Nature 443 803–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J. C. C., N. A. Oyler, W.-M. Yau and R. Tycko, 2005. Parallel β-sheets and polar zippers in amyloid fibrils formed by residues 10–39 of the yeast prion protein Ure2p. Biochemistry 44 10669–10680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.-Y., J.-Y. Lin, H.-C. Lee, H.-L. Wang and C.-Y. King, 2008. Strain-specific sequences required for yeast prion [PSI+] propagation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105 13345–13350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B., G. P. Newnam and Y. O. Chernoff, 2007. Prion species barrier between the closely related yeast proteins is detected despite coaggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104 2791–2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff, Y. O., A. P. Galkin, E. Lewitin, T. A. Chernova, G. P. Newnam et al., 2000. Evolutionary conservation of prion-forming abilities of the yeast Sup35 protein. Mol. Microbiol. 35 865–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson, T. W., R. S. Sikorski, M. Dante, J. H. Shero and P. Hieter, 1992. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene 110 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliften, P. F., L. W. Hillier, L. Fulton, T. Graves, T. Miner et al., 2001. Surveying Saccharomyces genomes to identify functional elements by comparative DNA sequence analysis. Genome Res. 11 1175–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinge, J., 1999. Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Lancet 354 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinge, J., and A. R. Clarke, 2007. A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science 318 930–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, T. G., 2002. Transmitting the signal of excess nitrogen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae from the Tor proteins to th GATA factors: connecting the dots. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26 223–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuille, J., and P. L. Chelle, 1939. Experimental transmission of trembling to the goat. C. R. Seances Acad. Sci. 208 1058–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Delneri, D., G. C. Tomlin, J. L. Wixon, A. Hutter, M. Sefton et al., 2000. Exploring redundancy in the yeast genome: an improved strategy for use of the cre-loxP system. Gene 252 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch, I. L., M. E. Bradley, J. Y. Hong and S. W. Liebman, 2001. Prions affect the appearance of other prions: the story of [PIN]. Cell 106 171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch, I. L., Y. O. Chernoff, V. V. Kushnirov, S. G. Inge-Vechtomov and S. W. Liebman, 1996. Genesis and variability of [PSI] prion factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 144 1375–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, A. G., V. M. H. Meikle and H. Fraser, 1968. Identification of a gene which controls the incubation period of some strains of scrapie in mice. J. Comp. Pathol. 78 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z., K.-W. Park, H. Yu, Q. Fan and L. Li, 2008. Newly identified prion linked to the chromatin-remodeling factor Swi1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Genet. 40 460–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edskes, H. K., V. T. Gray and R. B. Wickner, 1999. The [URE3] prion is an aggregated form of Ure2p that can be cured by overexpression of Ure2p fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 1498–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edskes, H. K., and R. B. Wickner, 2000. A protein required for prion generation: [URE3] induction requires the Ras-regulated Mks1 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 6625–6629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edskes, H. K., and R. B. Wickner, 2002. Conservation of a portion of the S. cerevisiae Ure2p prion domain that interacts with the full-length protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99(Suppl. 4): 16384–16391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, A. L., and J. H. McCusker, 1999. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15 1541–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, J. S., 1967. Self-replication and scrapie. Nature 215 1043–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, R. E., and I. Herskowitz, 1984. Directionality and regulation of cassette substitution in yeast. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 49 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, C. Y., and R. Diaz-Avalos, 2004. Protein-only transmission of three yeast prion strains. Nature 428 319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryndushkin, D., and R. B. Wickner, 2007. Nucleotide exchange factors for Hsp70s are required for [URE3] prion propagation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 18 2149–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnirov, V. V., N. V. Kochneva-Pervukhova, M. B. Cechenova, N. S. Frolova and M. D. Ter-Avanesyan, 2000. Prion properties of the Sup35 protein of yeast Pichia methanolica. EMBO J. 19 324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroute, F., 1971. Non-Mendelian mutation allowing ureidosuccinic acid uptake in yeast. J. Bacteriol. 106 519–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead, S., M. P. Stumpf, J. Whitfield, J. A. Beck, M. Poulter et al., 2003. Balancing selection at the prion protein gene consistent with prehistoric kurulike epidemics. Science 300 640–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayashiki, T., C. P. Kurtzman, H. K. Edskes and R. B. Wickner, 2005. Yeast prions [URE3] and [PSI+] are diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102 10575–10580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R., M. R. Sawaya, M. Balbirnie, A. O. Madsen, C. Riekel et al., 2005. Structure of the cross-β spine of amyloid-like fibrils. Nature 435 773–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, B. K., and S. W. Liebman, 2007. “Prion proof” for [PIN+]: infection with in vitro-made amyloid aggregates of Rnq1p-(132–405) induces [PIN+]. J. Mol. Biol. 365 773–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perutz, M. F., T. Johnson, M. Suzuki and J. T. Finch, 1994. Glutamine repeats as polar zippers: their possible role in inherited neurodegenerative diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91 5355–5358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, M. M., U. Baxa, A. C. Steven, A. Bax and R. B. Wickner, 2005. Is the prion domain of soluble Ure2p unstructured? Biochemistry 44 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner, S. B., 1982. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 216 136–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner, S. B., M. Scott, D. Foster, K.-M. Pan, D. Groth et al., 1990. Transgenic studies implicate interactions between homologous PrP isoforms in scrapie prion replication. Cell 63 673–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, C., M. L. Maddelein, A. B. Siemer, T. Luhrs, M. Ernst et al., 2005. Correlation of structural elements and infectivity of the HET-s prion. Nature 435 844–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, B. T., and R. B. Wickner, 2003. A class of prions that propagate via covalent auto-activation. Genes Dev. 17 2083–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, E. D., U. Baxa and R. B. Wickner, 2004. Scrambled prion domains form prions and amyloid. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 7206–7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, E. D., H. K. Edskes, M. J. Terry and R. B. Wickner, 2005. a Primary sequence independence for prion formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102 12825–12830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, E. D., A. P. Minton and R. B. Wickner, 2005. b Prion domains: sequences, structures and interactions. Nat. Cell Biol. 7 1039–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoso, A., P. Chien, L. Z. Osherovich and J. S. Weissman, 2000. Molecular basis of a yeast prion species barrier. Cell 100 277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlumpberger, M., S. B. Prusiner and I. Herskowitz, 2001. Induction of distinct [URE3] yeast prion strains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 7035–7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, F., 1991. Getting started with yeast, pp. 3–21 in Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology, edited by C. Guthrie and G. R. Fink. Academic Press, San Diego.

- Shewmaker, F., L. Mull, T. Nakayashiki, D. C. Masison and R. B. Wickner, 2007. Ure2p function is enhanced by its prion domain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 176 1557–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shewmaker, F., R. B. Wickner and R. Tycko, 2006. Amyloid of the prion domain of Sup35p has an in-register parallel β-sheet structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 19754–19759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipiczki, M., 2008. Interspecies hybridization and recombination in Saccharomyces wine yeasts. FEMS Yeast Res. 8 996–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talarek, N., L. Maillet, C. Cullin and M. Aigle, 2005. The [URE3] prion is not conserved among Saccharomyces species. Genetics 171 23–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M., P. Chien, N. Naber, R. Cooke and J. S. Weissman, 2004. Conformational variations in an infectious protein determine prion strain differences. Nature 428 323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate, J. J., and T. G. Cooper, 2007. Stress-responsive Gln3 localization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is separable from and can overwhelm nitrogen source regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 282 18467–18480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama, B. H., M. J. Kelly, J. D. Gross and J. S. Weissman, 2007. The structural basis of yeast prion strain variants. Nature 449 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turoscy, V., and T. G. Cooper, 1987. Ureidosuccinate is transported by the allantoate transport system in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 169 2598–2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallen, E. A., M. A. Hiller, T. Y. Scherson and M. D. Rose, 1992. Separate domains of KAR1i mediate distinct functions in mitosis and nuclear fusion. J. Cell. Biol. 117 1277–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner, R. B., 1994. [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: evidence for a prion analog in S. cerevisiae. Science 264 566–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner, R. B., F. Dyda and R. Tycko, 2008. a Amyloid of Rnq1p, the basis of the [PIN+] prion, has a parallel in-register β-sheet structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105 2403–2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner, R. B., F. Shewmaker, D. Kryndushkin and H. K. Edskes, 2008. b Protein inheritance (prions) based on parallel in-register β-sheet amyloid structures. BioEssays 30 955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]