Abstract

Objective To determine the efficacy of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography for healing of fractures.

Design Systematic review of randomised controlled trials.

Data sources Electronic literature search without language restrictions of CINAHL, Embase, Medline, HealthSTAR, and the Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials, from inception of the database to 10 September 2008.

Review methods Eligible studies were randomised controlled trials that enrolled patients with any kind of fracture and randomly assigned them to low intensity pulsed ultrasonography or to a control group. Two reviewers independently agreed on eligibility; three reviewers independently assessed methodological quality and extracted outcome data. All outcomes were included and meta-analyses done when possible.

Results 13 randomised trials, of which five assessed outcomes of importance to patients, were included. Moderate quality evidence from one trial found no effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on functional recovery from conservatively managed fresh clavicle fractures; whereas low quality evidence from three trials suggests benefit in non-operatively managed fresh fractures (faster radiographic healing time mean 36.9%, 95% confidence interval 25.6% to 46.0%). A single trial provided moderate quality evidence suggesting no effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on return to function among non-operatively treated stress fractures. Three trials provided very low quality evidence for accelerated functional improvement after distraction osteogenesis. One trial provided low quality evidence for a benefit of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography in accelerating healing of established non-unions managed with bone graft. Four trials provided low quality evidence for acceleration of healing of operatively managed fresh fractures.

Conclusion Evidence for the effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on healing of fractures is moderate to very low in quality and provides conflicting results. Although overall results are promising, establishing the role of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography in the management of fractures requires large, blinded trials, directly addressing patient important outcomes such as return to function.

Introduction

Each year in North America about 6 million people experience a fracture, of whom 5-10% show delayed healing or non-union.1 2 Clinicians can utilise several options to promote healing of fractures, including bone stimulators. A recent Canadian survey of 450 trauma surgeons (response rate 60%) found that 45% of respondents were using bone stimulators to manage tibial fractures, with use evenly divided between low intensity pulsed ultrasonography and pulsed electromagnetic field therapy.3

The Food and Drug Administration approved the use of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography for accelerating conservatively managed fresh fracture healing in 1994, and for treatment of established non-unions in 2000.4 Basic science research suggests that beneficial effects of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on bone healing may include a positive impact on signal transduction, gene expression, blood flow, and tissue modelling and remodelling.5 Sales of bone stimulators in the United States alone represented a $500m (£351m; €380m) market in 2006, with projections of 6% or 7% growth per year.6 Based on data that suggested low intensity pulsed ultrasonography may reduce time to healing of operatively managed tibial fractures by a mean of 32 days (154 v 122 days), one study estimated savings of $13 259 per fracture.7 This economic analysis considered both direct and indirect costs; however, data for this model were based on a case series of 60 patients and an ultrasound registry and used radiographic healing as a surrogate for functional recovery.

In the absence of high quality evidence of improved patient important outcomes such as decreased time to weight bearing and earlier return to function, the widespread use of bone stimulators represents an uncertain investment of limited healthcare resources. Previous systematic reviews on the clinical effectiveness of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography and pulsed electromagnetic field therapy have proved inconclusive and in the case of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography focused exclusively on trials published before 2001 that utilised radiographic healing as the end point.8 9 10 We carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials to determine the effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on bone fractures, focusing on patient important outcomes, in particular functional recovery.

Methods

Two reviewers (JWB and JK) independently identified relevant randomised controlled trials, in any language, by a systematic search of CINAHL, Embase, Medline, HealthSTAR, and the Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials, from inception of the database to 10 September 2008, with the following terms: (fracture healing or bony callus or bone remod* or fracture*, closed or fracture*, open) AND (ultrasonic therapy or ultrasonography). We used the wild card term “*” to increase the sensitivity of our search strategy. Reviewers scanned the bibliographies of all retrieved trials and other relevant publications, including reviews and meta-analyses, for additional relevant articles. We contacted Smith and Nephew, the manufacturer of the low intensity pulsed ultrasonography devices used in most trials, to inquire about any additional unpublished trials or trials in progress.

Eligibility criteria

Two reviewers (JWB and JK) screened the titles and abstracts of identified citations independently and in duplicate and acquired the full text of any article that either judged potentially eligible. These reviewers independently applied eligibility criteria to the methods section of potentially eligible trials. Eligible trials had to have randomly allocated patients presenting with any form of fracture to low intensity pulsed ultrasonography or to a control group. We resolved disagreements by discussion.

Data abstraction and analysis

Three reviewers (JWB, BM, and JK) extracted data from each eligible study independently and in triplicate. Data included personal information, methodology, details on interventions, and reported outcomes. Reviewers assessed study validity and applicability by appraising concealment of allocation, blinding, handling of withdrawals, cointerventions, compliance, similarity of timing of outcome assessment, and adherence to the intention to treat principle.11 12 The reviewers resolved disagreement by discussion. We attempted to contact study authors to settle any uncertainties.

Among eligible trials we found substantial diversity in the types of fractures targeted for treatment and the outcome measures used (table 1). Two experienced trauma surgeons (MB and PT third) grouped the participants into the five clinical categories of non-operatively managed fresh fractures, non-operatively managed stress fractures, distraction osteogenesis, bone grafting for non-union, and operatively managed fresh fractures (table 1). We separated trials according to clinical presentation but not the bone involved. Although baseline healing time differs by size of bone and the site of fracture, the process of healing is consistent across all fractured bones13 and the effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography compared with control on the time to fracture healing is therefore likely to be similar. We reasoned that pooling trials with the same intervention directed towards clinically similar fractures of different bones would increase the generalisability of our results.14

Table 1.

Characteristics of included trials

| Trial | Fracture location | No of patients randomised (No analysed) | Mean (SD) age | Duration of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography | Outcome measures recorded | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment group | Control group | ||||||

| Non-operative management | |||||||

| Fresh fracture: | |||||||

| Kristiansen et al 1997w2 | Distal radius | 40 (30) | 45 (31) | Treatment: 54 (3*); control: 58 (2*) | 70 days | Time to early trabecular bridging†; time to cortical bridging (first, second, third, and fourth)†; time to organised trabecular bridging† | |

| Mayr et al 2000w3 | Scaphoid | 15 (15) | 15 (15) | 37 (14) | Until cast was removed | Time to cast removal†; % of patients with bridging of fracture at 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 weeks†‡; time to ≥70% bridging of fracture† | |

| Heckman et al 1994w1 | Tibia | 48 (33); 31 closed, 2 grade I open | 49 (34); 33 closed, 1 grade I open | Treatment: 36 (2.3*); control: 31 (1.8*) | 140 days, or until study investigator deemed fracture was healed | Time to bridging of three cortices†; time to bridging of four cortices†; time to endosteal healing†; time to clinical healing (fracture stable and not painful to manual stress)†; time to cast removal†; days to start of weight bearing | |

| Lubbert et al 2008w15 | Clavicle | 61 (52) | 59 (49) | Treatment: 38 (13); control: 37 (12) | 28 days | Fracture consolidation according to patient; need for operative fixation; analgesic use; pain; adverse events; non-union; resumption of sport, professional, or household activities | |

| Stress fracture: | |||||||

| Rue et al 2004w4 | Tibia | 14 (14) | 12 (12) | Treatment: 18.6 (0.8); control: 18.4 (0.8) | Until fracture was asymptomatic and healed on x ray film | Return to full participation and duty | |

| Operative management | |||||||

| Distraction osteogenesis: | |||||||

| Schortinghuis et al 2005w5 | Mandible | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 65 (8.8) | From first day of distraction until implant inserted (mean 13.0 (SD 1.5) hours) | Microradiography gap fill area; gap grey percentage; histology gap fill length; histological score; patient ease of use questionnaire | |

| El-Mowafi and Mohsen 2005w6 | Tibia | 10 (10) | 10 (9) | 35 (range 18-45) | Until removal of external fixator | Healing index (duration of external fixation divided by length of distraction gap)† | |

| Tsumaki et al 2004w14 | Tibia | 21 (21) | 21 (21) | 68 (range 53-78) | Until removal of external fixator | Bone mineral density in distraction callus†; bone mineral density distal to distraction gap; consolidation period; duration of fixator use | |

| Bone graft for non-union: | |||||||

| Ricardo 2006w10 | Scaphoid | 10 (10) | 11 (11) | 26.7 (range 17-42) | Until fracture healed clinically and radiographically | Overall time to clinical (no pain or tenderness) and radiographic healing† | |

| Fresh fracture: | |||||||

| Handolin et al 2005w7 | Lateral malleolus | 11 (10) | 11 (11) | Treatment: 37.5 (range 18-54); control: 45.5 (range 26-59) | 42 days | Prevalence of fracture line visualisation at 2, 6, 9, and 12 weeks; prevalence of external callus formation at 2, 6, 9, and 12 weeks; % of bone healing at 2 and 9 weeks | |

| Handolin et al 2005w8 w9 | Lateral malleolus | 15 (15)§ | 15 (15)§ | Treatment: 41.4 (range 19-65); control: 39.4 (range 18-59) | 42 days | Prevalence of callus formation at 2 ,6, 9, and 12 weeks; radiographic healing at 72 weeks; Olerud-Molander score at 72 weeks; clinical examination of ankle at 72 weeks; bone mineral density at 12 and 72 weeks | |

| Emami et al 1999w11 w12 | Tibia | 15 (15)¶; 12 closed, 3 open | 17 (17)¶; 16 closed, 1 open | Treatment: 39.9; control: 34.3 | 75 days | Time to appearance of first callus; time to bridging of three cortices; time to full weight bearing; level of cross linked telopeptide over one year †**; level of bone specific alkaline phosphatase over one year; level of osteocalcin | |

| Leung et al 2004w13 | Tibia | 16 (16); 7 closed, 9 open | 14 (14); 6 closed, 8 open | 35.3 (range 22-61) | 90 days | Disappearance of tenderness at fracture site††; time to partial weight bearing; time to full weight bearing†; duration of external fixator use†; time to appearance of first, second, and third callus†; % change in bone mineral content at fracture site at 11 time points over 30 weeks†‡‡; % change in bone specific alkaline phosphatase at 13 time points over 30 weeks†§§ | |

*Standard error

†Difference between groups was statistically significantly (P<0.05) in favour of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography.

‡Significant differences were reported at weeks 4, 6, and 8.

§Only eight in each group were available for 17 week follow-up.

¶One patient was excluded from the study, but authors did not clarify from which group. For laboratory blood assays, only 30 patients were analysed (15 per group).

**Differences were only significant (lower level of cross linked telopeptide in low intensity pulsed ultrasonography group) at week 1.

††Leung et alw13 reported a significant difference in favour of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography, but reanalysis of their data with two sided t test showed non-significant difference between treatment and control groups (P=0.09).

‡‡Significant differences reported at weeks 6, 15, 18, and 21.

§§Significant differences reported at weeks 12, 18, and 27.

To facilitate pooling of trials that explored the effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on non-operatively managed fresh fractures, we considered the time to bridging of three cortices to be equivalent to the time to achieve 70% or more bridging of fracture. We considered the time to bridging of three cortices and time to appearance of the third callus as equivalent. In one trial in which the principal investigator and an independent radiologist assessed radiographic healingw1 we used data from the radiologist.

We used random effects meta-analyses, which are conservative as they consider differences both within and among studies in calculating the error term used in the analysis.11 For the outcomes of time to return to active duty and time to full weight bearing we presented pooled data in the original units of measurement. For the outcome of time to radiographic healing we carried out meta-analyses by using the inverse variance method to combine the natural logarithms of the ratio of the mean time to healing in the treatment group to the mean time to healing in the placebo group. We then converted the resulting combined estimate and presented it as a percentage decrease in time to healing in the treatment group compared with the placebo group.15

Meta-analyses of small trials can provide evidence of benefit with what seem to be narrow estimates of precision; however, such reviews have often been subsequently refuted by large trials. To address this potential concern we determined that in cases in which our meta-analysis suggested benefit with an associated narrow measure of precision, if the sample size was less than the optimal information size (the number of patients generated by a conventional sample size calculation for a single trial)16 then we would consider the result imprecise. For the purposes of calculating the optimal information size we assumed a treatment effect (Δ) of 20%, an α of 0.05, and a β of 0.20. Our choice of Δ was based on a recent survey of orthopaedic trauma surgeons (268 respondents) in which 80% reported that a reduction of six weeks in healing of tibial fractures, attributed to a bone stimulator, would be important to patients3 and the assumption that a typical course of healing for tibial fractures is about seven months.

We examined heterogeneity using both a χ2 test and the I2 statistic, the percentage of variability among studies that is due to true differences between studies (heterogeneity) rather than sampling error (chance).17 We considered an I2 value greater than 50% to reflect substantial heterogeneity.18 We generated three a priori hypotheses to explain variability between studies: fracture location, clinical category, and the technical specifications and application of ultrasound devices used. We did tests of interaction19 to establish if subgroups differed significantly from each other and used the criteria of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) to evaluate the quality of evidence by outcome.20

Results

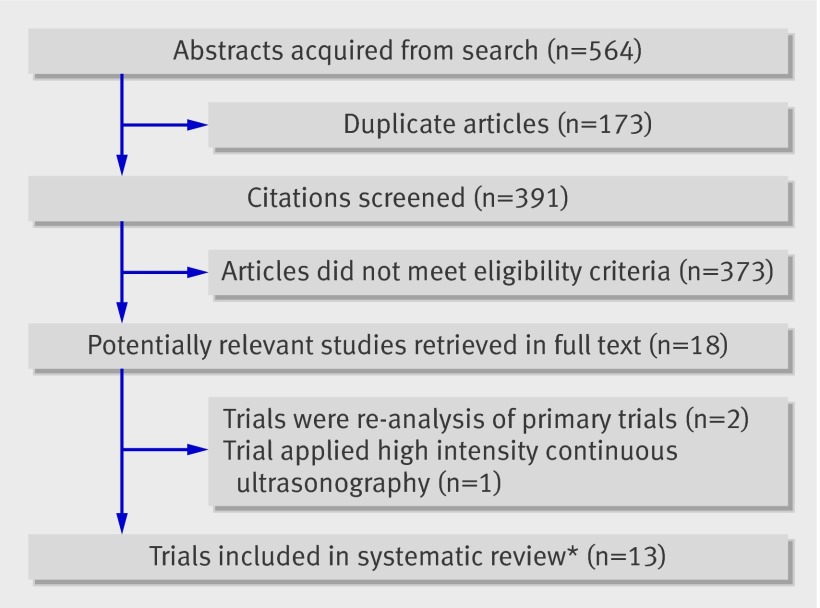

Overall, 564 potentially eligible studies were identified and 18 retrieved in full text.21 22 23 w1-w15 Two trials were not original21 22 and one made use of high intensity, continuous ultrasonography,23 leaving 15 eligible trials (fig 1).w1-w15 After adjustment for chance the agreement between reviewers (κ) on full text eligibility was 0.81 (95% confidence interval 0.68 to 0.94).

Fig 1 Flow of trials through study. *Two sets of trials reported on common patient samples and were considered as single studies

Two trialsw11 w12 seemed to report on a shared group of 30 participants as the participants had an identical match for age. In addition, according to the methods sections these participants were recruited at the same institution over the same period. Attempts to contact the authors of these trials for clarification were unsuccessful. The data from both studies are considered as one trial for reporting purposes (fig 1).

Three trials by the same group of authors, published in three different journals in 2005, reported on the effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on lateral malleolar fractures.w7-w9 Contact with the lead author confirmed that there were two distinct trials: one randomised trial of 22 patientsw7 and another of 30 patients.w8 w9 This left 13 unique trials for analysis (fig 1).

Most studies reported only surrogate end points; five explored end points of importance to patients (table 1). Eleven trials used imaging methods to assess bone healing. Six studies used plain films,w1 w2 w6 w10-w13 one used dual energy x ray absorptiometry scans,w14 two used both dual energy x ray absorptiometry scans and multidetector computed tomograms,w7-w9 one used high resolution microradiographs of fixed biopsies,w5 and onew3 used sagittal computed tomography to assess scaphoid healing.

Study quality

Eligible trials were of limited quality (table 2). Attempts were made to contact the authors of seven trials to resolve uncertainties,w3 w6-w10 w13 w15 and clarification was successful in four.w7-w10 w15 Eleven trials used a parallel design with random allocation of sham and active ultrasound devices; two did not use a sham device as their control.w3 w14 One trialw3 randomly assigned patients with non-operatively managed scaphoid fractures to usual care or to low intensity pulsed ultrasonography in addition to usual care, whereas another studyw14 randomly assigned one limb of patients who had undergone bilateral tibial osteotomy to ultrasonography and the other limb to control. Although one trialw13 stated that patients and care providers were blinded, the treatment and control devices were visually different. No study explicitly declared an intention to treat analysis, but no trials reported patient crossover and all patients were analysed according to the group to which they were randomly allocated. No trial described any cointerventions to which participants were exposed. Seven trials reported loss to follow-up, ranging from 3% to 47% (table 2), which in all cases was dealt with by excluding lost participants from both the numerator and denominator for all outcome calculations.

Table 2.

Methodological quality of eligible randomised controlled trials

| Trial | Concealment of treatment allocation | Patients blinded | Caregivers blinded | Outcome assessors blinded | Loss to follow-up (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-operative management | |||||

| Fresh fracture: | |||||

| Kristiansen et al 1997w2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 28 |

| Mayr et al 2000w3 | Unclear | No | No | Yes | 0 |

| Heckman et al 1994w1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 31 |

| Lubbert et al 2008w15 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 16 |

| Stress fracture: | |||||

| Rue et al 2004w4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 |

| Operative management | |||||

| Distraction osteogenesis: | |||||

| Schortinghuis et al 2005w5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 |

| El-Mowafi and Mohsen 2005w6 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 5 |

| Tsumaki et al 2004w14 | Yes | No | No | No | 0 |

| Bone graft for non-union: | |||||

| Ricardo 2006w10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 |

| Fresh fracture: | |||||

| Handolin et al 2005w7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Handolin et al 2005w8 w9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0% for 12 week follow-up; 47% for 18 month follow-up |

| Emami et al 1999w11 w12 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| Leung et al 2004w13 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 0 |

Trial ultrasound devices

In 12 of the eligible trials the treatment provided to the control group was indistinguishable from that provided to the treatment group, the exception being the trial in which the active and sham devices were similar but easily visually distinguishable.w13 In 12 of the 13 eligible studiesw1-w9 w11-w15 the investigators made use of the Sonic Accelerated Fracture Healing System (Exogen, Piscataway, NJ). The trials that used this device required their treatment groups to receive daily 20 minute sessions with an ultrasound signal composed of a burst width of 200 μs (SD 10%) containing 1.5 MHz (SD 5%) sine waves, with a repetition rate of 1 kHz (SD 10%) and a spatial average temporal intensity of 30 mW/cm2 (SD 30%). The settings of the ultrasound unit could not be modified and a warning signal was sounded for active devices if coupling to the skin was not achieved. Duration of ultrasound use varied between trials: five studies instructed patients to apply low intensity pulsed ultrasonography until their fracture was healed,w3 w4 w6 w10 w14 seven used a set time that ranged from 13 hours to 90 days,w2 w5 w7-w9 w11-w13 w15 and in one the patients applied low intensity pulsed ultrasonography up to a maximum of 140 days until their fracture was healed (table 1).w1

Five trials reported on patient compliance with low intensity pulsed ultrasonography.w1 w2 w5 w7 w11 w12 Compliance was measured by an elapsed time recorder that provided only the total time used and not the temporal picture of use and by a daily log book maintained by participants. All found high agreement between the internal device timer and patients’ log books, and that use of the device between treatment and control groups was not significantly different. One of the trialsw5 provided additional details on use of the device, noting that although the patients applied low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on a daily basis, treatment with the active device was interrupted in 11% of applications owing to disconnected cables, improper contact between transducer and skin, or a low battery; however, patients successfully corrected the error and resumed treatment in all cases but one.

One studyw10 used an alternate ultrasound device, the Theramed 101-B ultrasound device supplied by the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones en Metrología (Havana, Cuba). The signal intensity was 30 mW/cm2, and the device was described as low intensity pulsed ultrasound therapy. Patient’s applied this device for 20 minutes each day until radiographic healing, and active and sham units were blinded in the same manner as the Exogen device. None of the 13 eligible trials reported any adverse reactions or complications attributable to the device.

Outcomes

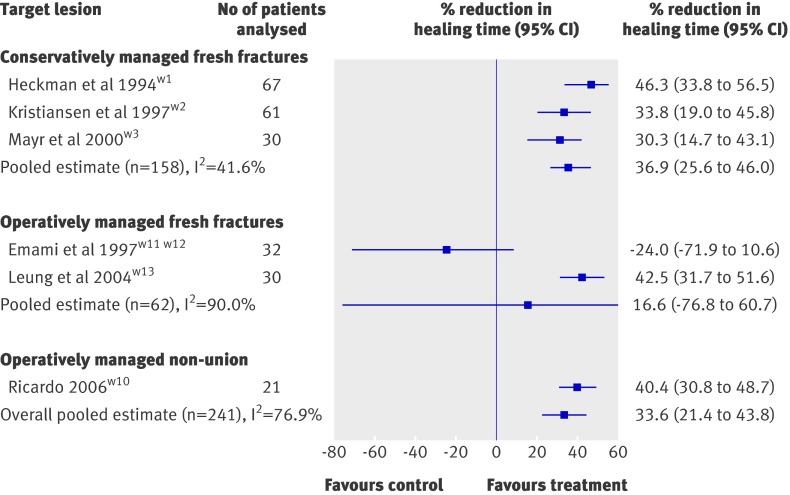

When time to radiographic healing—the most commonly reported end point among eligible trials—was pooled across all studies it showed a moderate effect in favour of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography. The pooled mean reduction in radiographic healing time was 33.6% (95% confidence interval 21.4% to 43.8%) but the associated heterogeneity was high (I2=76.9%; heterogeneity P<0.01; fig 2). Tests of interaction provided no evidence to support a different treatment effect across clinical presentations. The effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography was not significantly different between conservatively managed fresh fractures and operatively managed fresh fractures (P=0.48), between conservatively managed fresh fractures and operatively managed non-unions (P=0.61), or between operatively managed fresh fractures and operatively managed non-unions (P=0.39).

Fig 2 Effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on radiographic healing of fractures

Table 3 presents a detailed GRADE description for the effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on return to function or acceleration of radiographic healing of non-operatively managed fresh fractures, non-operatively managed stress fractures, operatively managed non-union, and operatively treated fresh fractures. Trials addressing distraction osteogenesis are not shown as they did not report any functional outcomes or any common surrogate end point.

Table 3.

GRADE evidence profile: randomised controlled trials of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography for more rapid return to function (often measured by surrogate of radiographic fracture healing)

| No of studies (No of patients) | Limitations | Consistency | Directness | Precision | Publication bias | Magnitude of effect (95% CI) | Overall quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-operatively managed fresh fractures | |||||||

| Return to function: | |||||||

| 1 trial (n=101) | No limitations | No important inconsistency | Direct | Imprecise* | Unlikely | Faster return to function† 1.40 days (−0.56 to 3.36) | Moderate |

| Radiographic healing: | |||||||

| 3 trials (n=158) | Limitations‡ | No important inconsistency | Indirect§ | Precision adequate | Potential¶ | Reduction in healing time 36.9% (25.6% to 46.0%) | Low |

| Non-operatively treated stress fractures | |||||||

| Return to function: | |||||||

| 1 trial (n=26) | No limitations | No important inconsistency | Direct | Imprecise* | Unlikely | Faster return to active duty 0.4 days (−13.1 to 13.9) | Moderate |

| Operatively managed non-union | |||||||

| Radiographic healing: | |||||||

| 1 trial (n=21) | No limitations | No important inconsistency | Indirect§ | Imprecise** | Potential¶ | Reduction in healing time 40.4% (30.8% to 48.7%) | Low |

| Operatively managed fresh fractures | |||||||

| Return to function: | |||||||

| 2 trials†† (n=61) | Serious limitations‡‡ | Important inconsistency | Direct | Imprecise* | Unlikely | Faster return to full weight bearing 3.4 weeks (−2.1 to 8.9) | Low |

| Radiographic healing: | |||||||

| 2 trials (n=61) | Serious limitations‡‡ | Important inconsistency | Indirect§ | Imprecise* | Unlikely | Reduction in healing time 16.6% (−76.8% to 60.7%) | Very low |

*95% confidence interval included both important benefit and harm.

†As patient assessed fracture healing, resumption of household activities, return to work, and resumption of sport measure same underlying domain (functional recovery), data from these four end points were pooled to improve precision of outcome measure.

‡Loss to follow-up was about 30% in two trials, and third trial did not blind participants or providers and it is not certain that allocation was concealed.

§Evidence is provided by surrogate measure only (radiographic healing).

¶As a result of small number of trials and inconsistent reporting of outcomes across trials. Overall quality rating was not decreased on basis of suspicion of publication bias.

**Although confidence interval appears adequately narrow, the sample size failed to meet the optimal information size.

††A third, negative, trial by Handolin et alw9 reported on a functional outcome, mean Olerud-Molander score, but did not provide the associated measure of variance to allow for statistical pooling.

‡‡Uncertain if, in positive trial by Leung et alw13, allocation was concealed or if patients, care givers, or outcome assessors were blinded. Quality was not, however, downgraded.

Non-operatively managed fresh fractures

One study found no effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on conservatively managed, isolated, clavicle shaft fractures.w15 Subjective fracture consolidation among patients treated with low intensity pulsed ultrasonography occurred in a mean 26.8 days compared with 27.1 days in the control (mean difference 0.3 days, 95% confidence interval −5.3 to 5.9), and no significant differences were found between groups in need for operative fixation, analgesic use, pain, adverse events, or resumption of sport, professional, or household activities. As patient assessed fracture healing, resumption of household activities, return to work, and resumption of sport measure the same underlying domain (functional recovery), a random effects model was used to pool data from these four end points to improve the precision of this outcome measure. The pooled standardised mean difference found that treatment with low intensity pulsed ultrasonography resulted in a non-significantly faster return to function by 1.4 days (95% confidence interval −0.6 to 3.4; I2=11.4%; heterogeneity P=0.34).

Low intensity pulsed ultrasonography significantly accelerated radiographic healing of fractures in all three trials that assessed this outcome.w1-w3 One trial found a 33.8% reduction in healing time, with distal radial fractures healing in 51 days compared with 77 days in the control group (mean difference 26 days, 95% confidence interval 6.4 to 38.6).w2 A second trial found a 30.3% reduction in healing time of scaphoid fractures; 43.2 days in the low intensity pulsed ultrasonography group compared with 62.0 days in the control group (mean difference 18.8 days, 7.6 to 30.0).w3 The authors did not specify the unit of their associated measures of variance, and for our analysis standard deviations were assumed. A third trial found a 46.3% reduction in healing time of tibial shaft fractures: 102 days in the low intensity pulsed ultrasonography group compared with 190 days in the control group (mean difference 88 days, 50.4 to 125.6).w1 This trial also found a significant improvement in surgeon assessed clinical healing (fracture stable and not painful to manual stress) of 86 days compared with 114 days (mean difference 28 days, 4.9 to 51.1), but not in time to partial weight bearing (45 days in the low intensity pulsed ultrasonography group v 49 days in the control group; mean difference 4 days, −11.0 to 19.0).15

The pooled results from the three trialsw1-w3 found a significant mean reduction in radiographic healing time of 36.9% (95% confidence interval 25.6% to 46.0%; I2=41.6%; heterogeneity P=0.18; fig 2). Calculating a Δ of 20% relevant to the control data for each trial (15, 12, and 38 days) and using the standard deviation associated with fracture healing in the three studies (31.6, 15.8, and 37.6 days) yields corresponding required sample sizes of 140, 56, and 32. The 158 patients available for this analysis therefore meet the optimal information size. Low quality evidence from three trials suggests a benefit of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography in non-operatively managed fresh fractures (tables 2 and 3).w1-w3

Non-operatively managed stress fractures

One studyw4 noted no improvement in return to full participation and duty among midshipmen sick listed because of tibial stress fractures. Patients treated with low intensity pulsed ultrasonography returned to active duty in a mean 55.8 days compared with 56.2 days for those receiving sham therapy (mean difference 0.4 days, 95% confidence interval −13.4 to 14.2). This trial provided moderate quality evidence of no effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on return to function among non-operatively treated stress fractures (tables 2 and 3).

Operatively managed distraction osteogenesis

One studyw5 found no effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography in the stimulation of bone formation in the distraction gap created in severely resorbed mandibles, and suggested that future trials consider a longer consolidation period than 31 days. Another studyw6 found that low intensity pulsed ultrasonography accelerated radiographic healing in patients with tibial defects managed with distraction osteogenesis. The authors used a “healing index” as their outcome, which was defined as the duration of external fixation divided by the length of distraction gap. Patients using active low intensity pulsed ultrasonography had a healing index of 30 days/cm compared with 48 days/cm for those exposed to a sham device (mean difference 18.0 days/cm, 95% confidence interval 11.7 to 24.3). One studyw14 administered low intensity pulsed ultrasonography or sham treatment to patients undergoing opening wedge high tibial osteotomy to tackle varus deformity secondary to osteoarthritis. The authors noted that low intensity pulsed ultrasonography compared with sham treatment resulted in a significant increase in mean bone mineral density in the distraction callus (0.20 g/cm2 v 0.13 g/cm2; mean difference 0.07 g/cm2, 95% confidence interval 0.003 to 0.14) but not in bone mineral density distal to the distraction gap, nor in the mean consolidation period or duration of external fixator use. The authors did not specify the unit of their associated measures of variance, and for our analysis these were assumed to be standard deviations. Three trials provided very low quality evidence for accelerated functional improvement after distraction osteogenesis (table 2).w5 w6 w14

Operatively managed (bone graft) non-union

In one studyw10 the application of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography to patients with established scaphoid non-union and treated with vascularised pedicle bone graft compared with those exposed to a sham device accelerated healing by a mean difference of 38 days (95% confidence interval 26.3 to 49.7), which represents a 40.4% (95% confidence interval 30.8% to 48.7%) reduction in healing time (fig 2). Communication with the author established that the reported associated measures of variance were standard errors of the mean, and these were converted to standard deviations. To be considered healed, patients had to present with no tenderness at the scaphoid and show complete bridging of cortices on plain radiographs. Calculating a Δ of 20% relevant to the control data (94×0.2=19 days) and using the standard deviation associated with fracture healing (27 days) yielded a required sample size of 64. The 21 patients available for this analysis therefore did not meet the optimal information size. This trial provided low quality evidence for a benefit of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography in accelerating healing of established non-unions managed with bone graft (tables 2 and 3).

Operatively managed fresh fractures

Functional outcomes were inconsistent. One trial of patients with lateral malleolar fractures fixed using bioabsorbable screws found no differences in function at 18 months.w9 One trial of operatively managed tibial shaft fractures found no difference in time to full weight bearing (6.5 weeks for low intensity pulsed ultrasonography v 7.1 weeks for sham therapy; mean difference 0.6 weeks, −1.5 to 2.7).w11 w12 One trial of operatively managed tibial fractures reported that low intensity pulsed ultrasonography reduced average time to disappearance of site tenderness. Our reanalysis of the results found that this difference was not significant (6.1 weeks v 7.9 weeks; mean difference 1.8 weeks, −0.2 to 3.8, P=0.09). The authors did find that low intensity pulsed ultrasonography reduced time to full weight bearing (9.3 weeks v 15.5 weeks; mean difference 6.2 weeks, 4.4 to 8.0); there was no difference in time to partial weight bearing.w13

Two trialsw7-w9 of patients with lateral malleolar fractures fixed using bioabsorbable screws and treated with low intensity pulsed ultrasonography or a sham device found no significant differences in visualisation of the fracture line, external callus formation, percentage of bone healing, or bone mineral density. One studyw11 w12 found that low intensity pulsed ultrasonography had no effect on radiographic healing among patients with operatively managed (intramedullary nail) tibial shaft fractures. Active treatment resulted in a non-significant mean time to bridging of three cortices of 155 days compared with 125 days for sham treatment (mean difference 30 days, 95% confidence interval −16.5 to 76.5; fig 2). Leung et alw13 explored the effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on operatively managed tibial fractures and found that it reduced time to removal of external fixator (9.9 weeks v 17.1 weeks; mean difference 7.2 weeks, 2.6 to 11.8) and time to first, second, and third callus formation; specifically, patients receiving active treatment showed formation of the third callus in an average of 11.5 weeks compared with 20 weeks for those receiving sham therapy (mean difference 8.5 weeks, 5.8 to 11.2), a 42.5% (95% confidence interval 31.7% to 51.6%) reduction in radiographic healing time (fig 2).

The pooled results from two trialsw11-w13 showed a non-significant mean reduction in radiographic healing time of 16.6% (−76.8% to 60.7%; I2=90.9%; heterogeneity P<0.01; fig 2). Four trials provided low quality evidence for acceleration of healing of operatively managed fresh fractures (tables 2 and 3).w7-w9 w11-w13

Discussion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis of eligible randomised controlled trials found moderate to very low quality evidence for low intensity pulsed ultrasonography in accelerating functional recovery among patients with fracture; only five of 13 trials directly assessed functional end points (time to return to active duty,w4 Olerud-Molander scorew9; time to full weight bearingw11-w13; time to patient reported fracture healing and resumption of household activities, work, or sportsw15); of these, one was positive.w13 The two trials providing the highest quality evidence (table 3) showed no difference in functional outcome.w4 w15

Quality of evidence

Our findings are strengthened by the comprehensive search and broad clinical eligibility criteria (including trials in any language), and by including only randomised controlled trials. In the GRADE system of rating quality of evidence for each outcome,20 24 randomised trials begin as high quality evidence but may be rated down by one or more of five categories of limitations. The eligible trials in our analysis had methodological limitations including lack of blinding of all relevant parties and substantial loss to follow-up in some trials. Results were sometimes inconsistent across trials, and most studies used surrogate end points; larger effects were typically reported for surrogates compared with direct measures of function. Concerns about publication bias arose from the limited number of small trials,25 and the inconsistent reporting of outcomes across trials raises the possibility of selective reporting bias,26 although we did not rate down the evidence for publication bias or selective reporting bias. The strength of inference is therefore limited.

Furthermore, two eligible trials did not specify the unit of measurement for their reported measures of variancew3 w14 and we were unable to clarify this information. We assumed that they reported standard deviations; however, three other eligible trials in our review reported the standard error of the meanw1 w2 w11 w12 and clarification with the author of another trial in which the unit of measurement was unclear established that they reported the standard error.w10 If our assumption was incorrect, and the authors of the two trials in questionw3 w14 reported the standard error, their results would become non-significant.

Implications for clinical practice and research

Recent Canadian surveys have found that 40% of senior residents in orthopaedic surgery (n=20) and 21% of trauma surgeons (n=268) are currently using low intensity pulsed ultrasonography as part of their management of tibial fractures.3 27 A 2008 narrative review in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, American edition, that failed to include negative trials, said there is “overwhelmingly positive clinical data supporting low-intensity pulsed ultrasound as a treatment for fracture repair.”5 Our results, however, suggest that despite the relatively common use of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography to enhance the healing of fractures the available evidence is only moderate to very low, few trials report on patient important outcomes (for example, time to full weight bearing or return to function), and of the five that didw4 w9 w11-w13 w15 only one reported a benefit.w13 Evidence to support the use of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography in operatively managed fresh fractures is inconsistent—inconsistency may (or may not) be explained by differences in the patient populations or by duration of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography use. A negative trialw11 w12 enrolled almost all closed tibial fractures and applied low intensity pulsed ultrasonography for 75 days, whereas a positive trialw13 enrolled mostly open tibial fractures and applied low intensity pulsed ultrasonography for 90 days. Future trials of the effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on operatively managed fresh tibial fractures may enhance their usefulness by including a range of injury severity and stratifying by open and closed fractures, and by instructing patients to administer low intensity pulsed ultrasonography until their fracture is healed or until maximum likely healing has occurred (for example, no evidence of additional radiographic healing is apparent on two consecutive follow-up radiographs).

Even where the evidence for accelerating radiographic healing with low intensity pulsed ultrasonography is stronger, such as in conservatively managed fresh fractures, reduction in healing time as measured by plain films may not translate into patient important benefit. Nevertheless, low intensity pulsed ultrasonography may provide important benefits to patients with fracture through accelerated improvement in function. Large trials of high methodological quality focusing on patient important outcomes such as quality of life and return to function are needed to establish whether this is the case.

What is already known on this topic

Low intensity pulsed ultrasonography is commonly used to improve the healing of fractures

What this study adds

Evidence to support the use of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography for fracture healing is limited and inconsistent; most trials report surrogate outcomes

Large, methodologically sound, trials on the effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasonography on fractures, particularly operatively managed fresh fractures and non-union, and that measure patient important outcomes are needed

We thank Wolfram Bosenberg for translating web reference 3. JWB is funded by a new investigator award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation. MB is supported in part by a Canada research chair, McMaster University. HJS is funded by a European Commission: the human factor, mobility and Marie Curie Actions, scientist reintegration grant (IGR 42192).

Contributors: JWB, MB, and GHG were involved in the study design and concept. JWB, JK, and BM collected the data. JWB and GHG did the analysis. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version. JWB is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: JWB, MB, and GHG are currently involved in a multicentre, randomised controlled trial that has received partial funding from Smith and Nephew, the company that manufactures Exogen. GHG and HJS are members of the GRADE working group.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b351

References

- 1.Musculoskeletal injuries: frequency of occurrence. In: Praemer A, Furner S, Rice DP, eds. Musculoskeletal conditions in the United States. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 1999:83-8.

- 2.Einhorn TA. Enhancement of fracture-healing. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1995;77:940-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busse JW, Morton E, Lacchetti C, Guyatt GH, Bhandari M. Current management of tibial shaft fractures: a survey of 450 Canadian orthopedic trauma surgeons. Acta Orthop 2008;79:689-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin C, Bolander M, Ryaby JP, Hadjiargyrou M. The use of low-intensity ultrasound to accelerate the healing of fractures. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2001;83:259-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan Y, Laurencin CT. Fracture repair with ultrasound: clinical and cell-based evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2008;90:138-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wachovia Capital Markets. Equity research: bone growth stimulation 2008 outlook. 5 Dec, 2007.

- 7.Heckman JD, Sarasohn-Kahn J. The economics of treating tibia fractures. The cost of delayed unions. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 1997;56:63-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busse JW, Bhandari M, Kulkarni AV, Tunks E. The effect of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound therapy on time to fracture healing: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2002;166:437-41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akai M, Hayashi K. Effect of electrical stimulation on musculoskeletal systems: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Bioelectromagnetics 2002;23:132-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mollon B, da Silva V, Busse JW, Einhorn TA, Bhandari M. Electrical stimulation for long-bone fracture healing: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2008;90:2322-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Reviewers’ Handbook 4.2.6, Updated September 2006. Oxford, UK: Cochrane Collaboration, 2006.

- 12.Boutron I, Moher D, Tugwell P, Giraudeau B, Poiraudeau S, Nizard R, et al. A checklist to evaluate a report of a nonpharmacological trial (CLEAR NPT) was developed using consensus. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:1233-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Day SM, Ostrum RF, Chao EYS, Rubin CT, Aro HT, Einhorn TA. Bone injury, regeneration, and repair. In: Buckwalter JA, Einhorn TA, Simon SR, eds. Orthopaedic basic science: biology and biomechanics of the musculoskeletal system. 2nd ed. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2000:371-99.

- 14.Gøtzsche PC. Why we need a broad perspective on meta-analysis: it may be crucially important for patients. BMJ 2000;321:585-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleiss JL. The statistical basis of meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res 1993;2:121-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pogue JM, Yusuf S. Cumulating evidence from randomized trials: utilizing sequential monitoring boundaries for cumulative meta-analysis. Control Clin Trials 1997;18:580-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ 2003;326:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pilla AA, Figueiredo M, Nasser PR, Alves JM, Ryaby JT, Klein M, et al. Acceleration of bone repair by pulsed sine wave ultrasound: animal, clinical and mechanistic studies. In: Brighton CT, Pollock SR, eds. Electromagnetics in biology and medicine. San Francisco, CA: San Francisco Press, 1991:331-41.

- 22.Cook SD, Ryaby JP, McCabe J, Frey JJ, Heckman JD, Kristiansen TK. Acceleration of tibia and distal radius fracture healing in patients who smoke. Clin Orthop 1997;337:198-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basso O, Pike JM. The effect of low frequency, long-wave ultrasound therapy on joint mobility and rehabilitation after wrist fracture. J Hand Surg (Br) 1998;23:136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, Addrizzo-Harris D, Hylek EM, Phillips B. Grading strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in clinical guidelines: report from an American College of Chest Physicians task force. Chest 2006;129:174-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song F, Eastwood AJ, Gilbody S, Duley L, Sutton A. Publication and related biases. Health Technol Assess 2000;4:111-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan AW, Hrobjartsson A, Haahr MT, Gotzsche PC, Altman DG. Empirical evidence for selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials: comparison of protocols to published articles. JAMA 2004;291:2457-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Busse JW, Bhandari M. Therapeutic ultrasound and fracture healing: a survey of beliefs and practices. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:1653-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]