Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Nitroglycerine (GTN) is an organic nitrate that has been used for more than 100 years. Despite its widespread clinical use, several aspects of the pharmacology of GTN remain elusive. In a recent study, the authors of the present study showed that GTN causes opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

OBJECTIVE:

In the present study, it was tested whether GTN-induced ROS production depends on mitochondrial potassium ATP-dependent channel or mPTP opening, and/or GTN biotransformation.

METHODS AND RESULTS:

Isolated rat heart mitochondria were incubated with succinate (a substrate for complex II) and GTN, causing immediate ROS production, as manifested by chemiluminescence. This ROS production was prevented by concomitant vitamin C incubation. Conversely, inhibitors of potassium ATP-dependent channels, mPTP opening or of GTN biotransformation did not modify ROS production.

CONCLUSIONS:

GTN triggers mitochondrial ROS production independently of the opening of mitochondrial channels and/or of GTN biotransformation. The present data, coupled with previous evidence published by the same authors that GTN causes opening of mPTPs, provide further evidence on the pharmacology of GTN. It is proposed that GTN causes direct uncoupling of the respiratory chain, which determines ROS production and subsequent mPTP opening. The clinical implications of these findings are also discussed.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Nitroglycerine, Reactive oxygen species

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

La nitroglycérine (GTN) est un nitrate organique utilisé depuis plus de 100 ans. Malgré son utilisation clinique généralisée, plusieurs aspects de sa pharmacologie demeurent imprécis. Dans une étude récente, les auteurs de la présente étude démontraient que la GTN est responsable de l’ouverture des pores de transition de la perméabilité mitochondriale (mPTP) et de la production mitochondriale d’espèces d’oxygène réactif (EOR).

OBJECTIF :

Dans la présente étude, on a évalué si la production d’EOS induite par la GTN dépend des canaux potassiques ATP-dépendants, de l’ouverture des mPTP, de la biotransformation de la GTN ou de tous ces phénomènes.

MÉTHODOLOGIE ET RÉSULTATS :

On a incubé les mitochondries isolées du cœur de rats avec du succinate (un substrat du complexe II) et de la GTN, ce qui a provoqué la production immédiate d’EOR, manifeste par chimiluminescence. On a empêché cette production d’EOR par une incubation concomitante de vitamine C. Par contre, les inhibiteurs des canaux potassiques ATP-dépendants, de l’ouverture des mPTP ou de la biotransformation de la GTN ne modifiaient pas la production des EOR.

CONCLUSIONS :

La GTN déclenche la production d’EOR mitochondriales, quelle que soit l’ouverture des canaux mitochondriaux ou la biotransformation de la GTN. Les présentes observations, couplées aux résultats probants publiés par les mêmes auteurs selon lesquelles la GTN est responsable de l’ouverture des mPTP, fournissent de nouvelles données probantes sur la pharmacologie de la GTN. On postule que la GTN provoque un découplage direct de la chaîne respiratoire qui détermine la production d’EOR et l’ouverture subséquente des mPTP. On discute également des répercussions cliniques de ces observations.

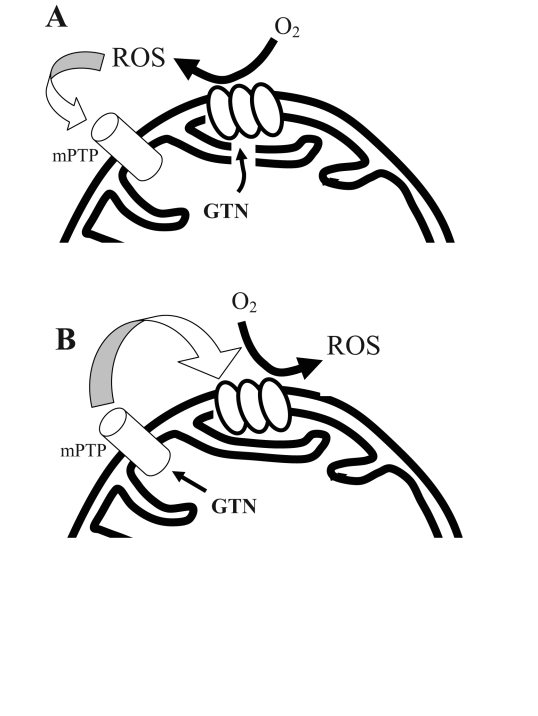

Nitroglycerine (GTN) is one of the oldest and yet most commonly used drugs in the therapy of cardiovascular patients. Pharmacologically, GTN is a prodrug that undergoes metabolization within the mitochondrial matrix (1) to release nitric oxide or a nitric oxide-containing compound. Several aspects of GTN pharmacology remain incompletely understood. Of importance, we recently documented that exposure to GTN causes a rapid increase in mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (2), and it has been shown that this may depend on the uncoupling of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (3). Furthermore, we recently demonstrated that this GTN-triggered ROS production is responsible for GTN-induced ischemic preconditioning (a short-term beneficial effect of GTN-induced ROS) (4) and GTN tolerance occurring in concert with the development of endothelial dysfunction (a long-term toxic effect of GTN-derived ROS) (5). It has also been demonstrated that opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) is critical in GTN-induced preconditioning (4). Because mPTP opening causes depolarization of the mitochondrial inner membrane (6), a direct effect of GTN on the mPTP may represent a mechanism for GTN-induced ROS production. Importantly, mPTPs are, in turn, opened by ROS (7); therefore, mPTP opening may represent both a cause and/or an effect of ROS production (Figure 1). Similarly, ATP-dependent potassium (K-ATP) channel opening may be another source of ROS. Although direct evidence of GTN-induced K-ATP opening has never been reported, it has been shown that K-ATP inhibition attenuates GTN tolerance in vitro (8). Therefore, we set out to test, in vitro, whether GTN-induced ROS production is influenced by the inhibition of mPTP opening, K-ATP channels or GTN biotransformation.

Figure 1).

The relationship between reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation and mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening. Two alternatives are possible: A Nitroglycerine (GTN)-derived ROS cause mPTP opening or B GTN directly triggers the opening of the pore, which causes respiratory uncoupling and further ROS production

METHODS

All animals were treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki <www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm> and with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the National Institutes of Health.

GTN-induced mitochondrial ROS production

ROS production was measured in isolated Wistar rat cardiac mitochondria according to methods previously described (9). Mitochondrial protein (35 μg, diluted to 500 μL) and the dye L-012 (100 μM) were used to measure ROS in the presence of succinate (4 mM final concentration). The chemiluminescence signal (Berthold Technologies, Germany) was expressed as counts per minute at 5 min. Mitochondrial ROS production was assessed in control conditions and in the presence of GTN 200 μM – a concentration that triggers, in vitro, approximately a 70% increase in mitochondrial ROS production, which is an effect similar to that observed after in vivo GTN administration (9). GTN-induced ROS production was then measured in the presence of the antioxidant vitamin C 100 μM, glibenclamide 10 μM (an inhibitor of K-ATP channel opening [8]), cyclosporine 0.2 μM (an inhibitor of mPTP [10]) and benomyl 100 μM (an inhibitor of the aldehyde dehydrogenase – the enzyme responsible for GTN biotransformation [1]). Each condition was compared with the corresponding vehicle. Experiments were performed using mitochondria isolated from at least two animals for each condition. Of note, because the experiments were performed in isolated mitochondria, the use of mitochondria-selective channel inhibitors was not necessary.

Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SE. Mitochondrial ROS data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Post hoc comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni correction. P<0.05 was set as the threshold for significance. StatView version 5 (SAS Institute Inc, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

GTN-dependent mitochondrial ROS production

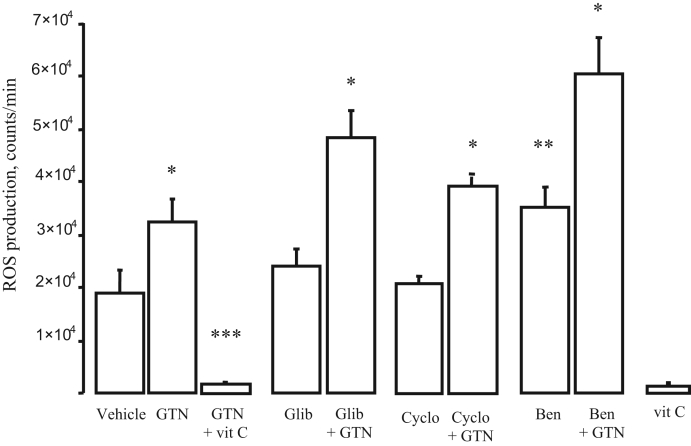

In vitro data are presented in Figure 2. Incubation with GTN caused a significant increase in mitochondrial ROS production (70±23% from baseline, n=7) that was abolished by vitamin C (n=10). While glibenclamide alone (n=12) and cyclosporine alone (n=8) did not significantly modify ROS production, benomyl (n=7) increased it (P<0.05) compared with control conditions. Of note, increased ROS production after exposure to benomyl has been previously described (11). Importantly, showing that K-ATP channels, mPTP and GTN biotransformation by the mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase are not necessary for GTN-induced ROS production, incubation with glibenclamide, cyclosporine or benomyl did not modify the increase in chemiluminescence counts after GTN (101±21%, 73±19% and 91±9%, respectively, over corresponding baseline; P not significant between groups; n=7 for glibenclamide, n=8 for cyclosporine, n=5 for benomyl). ROS production in the presence of vitamin C alone (n=5) was not different from that measured with vitamin C plus GTN.

Figure 2).

Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) counter data. Nitroglycerine (GTN) alone caused a significant increase in ROS counts, an effect that was entirely abrogated by vitamin C (vit C) (P not significant compared with vit C alone). Glibenclamide (Glib), cyclosporine (Cyclo) and benomyl (Ben) did not modify this effect of GTN. *P<0.05 compared with corresponding control, **P<0.05 compared with vehicle, ***P<0.01 compared with all groups

DISCUSSION

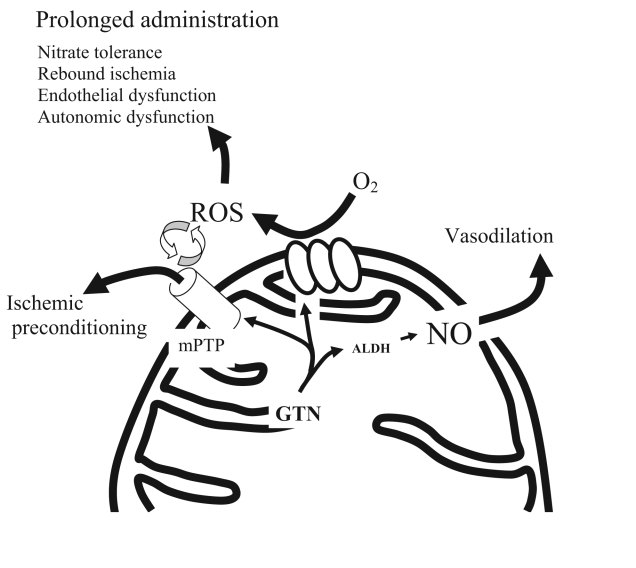

The bioactivation of GTN to nitric oxide or a nitric oxide-containing adjunct is mediated by reduction by mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase, an enzyme that is sensitive to oxidative stress (1,12). It has recently been shown (1) that this enzyme contains reduced thiol groups, which are critical for its function, and the oxidation of these groups on prolonged administration of GTN has been advocated to be an important mechanism of GTN tolerance. Furthermore, other potentially detrimental effects of GTN-induced ROS have been demonstrated. These include endothelial and autonomic dysfunction, as well as the activation of matrix metalloproteinases (13). Conversely, we recently demonstrated (14) that GTN-triggered ROS production is responsible for GTN-induced preconditioning, in a paradoxically protective effect of ROS. We also demonstrated that mPTP opening is crucial for this latter property of GTN (4). Because mPTP and K-ATP channel opening can theoretically be up- and downstream of GTN-induced ROS (10), the present study tested whether inhibition of these channels or of GTN biotransformation prevents GTN-induced ROS production. The present in vitro data showed that ROS production is independent of mPTP opening. Also, GTN-induced ROS production seems to be independent of K-ATP channel opening and of GTN biotransformation. While the mechanism of GTN-induced ROS remains to be clarified, the evidence presented here allows for a new hypothesis for GTN pharmacology: we propose that GTN causes transient mitochondrial uncoupling (at the level of complex I [3], but also downstream, as demonstrated by the induction of ROS in the presence of succinate – a substrate for complex II), leading to ROS production and subsequent transitory mPTP opening. The GTN-derived mitochondrial ROS possess other effects that may be as important as their hemodynamic effects. These include ischemic preconditioning on short-term GTN administration, the toxic effects of nitrates (reviewed in references 13 and 15), via oxidative damage, on prolonged administration and potentially additional but as yet undiscovered effects (16). In a process that is separate from ROS production, GTN undergoes mitochondrial metabolism to release a nitric oxide-containing compound. This compound is responsible for the ‘classic’ effects of GTN, including vasodilation, as well as the inhibition of platelet and leukocyte adhesion. Taken together, these data provide a new view on the mechanisms of action of organic nitrates and emphasize the need for a critical reappraisal of the effects of this class of drugs.

Figure 3).

A novel mechanism for nitroglycerine (GTN) pharmacology In this hypothesis, GTN undergoes metabolism to release nitric (NO), with its hemodynamic effects. Concurrently, it causes oxygen species (ROS) production, which has dual effects: protective (acutely) and toxic (chronically). ALDH Aldehyde dehydrogenase; mPTP Mitochondrial permeability transition pore

Footnotes

FUNDING: Dr Tommaso Gori is the recipient of a grant from Italian Ministry of Research. Dr John D Parker holds a Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation Ontario. The study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institute for Health Research. Drs Andreas Daiber and Münzel receive funding from the German Research Foundation (SFB SS3, C17).

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen Z, Stamler JS. Bioactivation of nitroglycerin by the mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16:259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sydow K, Daiber A, Oelze M, et al. Central role of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species in nitroglycerin tolerance and cross-tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:482–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI19267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esplugues JV, Rocha M, Nuñez C, et al. Complex I dysfunction and tolerance to nitroglycerin: An approach based on mitochondrial–targeted antioxidants. Circ Res. 2006;99:1067–75. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250430.62775.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gori T, Di Stolfo G, Sicuro S, et al. Nitroglycerin protects the endothelium from ischaemia and reperfusion: Human mechanistic insight. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:145–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gori T, Parker JD. Nitrate tolerance: A unifying hypothesis. Circulation. 2002;106:2510–3. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000036743.07406.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zoratti M, Szabò I. The mitochondrial permeability transition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1241:139–76. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(95)00003-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zorov DB, Filburn CR, Klotz LO, Zweier JL, Sollott SJ. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: A new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1001–14. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghatta S, O’Rourke ST. Nitroglycerin-induced release of calcitonin gene-related peptide from sensory nerves attenuates the development of nitrate tolerance. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;47:175–81. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000199681.35825.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daiber A, Oelze M, August M, et al. Detection of superoxide and peroxynitrite in model systems and mitochondria by the luminol analogue L-012. Free Radic Res. 2004;38:259–69. doi: 10.1080/10715760410001659773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hausenloy DJ, Maddock HL, Baxter GF, Yellon DM. Inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening: A new paradigm for myocardial preconditioning? Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55:534–43. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00455-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banks D, Soliman MR. Protective effects of antioxidants against benomyl-induced lipid peroxidation and glutathione depletion in rats. Toxicology. 1997;116:177–81. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(96)03542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenzel P, Hink U, Oelze M, et al. Role of reduced lipoic acid in the redox regulation of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH-2) activity. Implications for mitochondrial oxidative stress and nitrate tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:792–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606477200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gori T, Fineschi M, Parker JD, Forconi S. Current perspectives. Therapy with organic nitrates: Newer ideas, more controversies. Ital Heart J. 2005;6:541–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gori T, Forconi S. The role of reactive free radicals in ischemic preconditioning – clinical and evolutionary implications. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2005;33:19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Münzel T, Daiber A, Mülsch A. Explaining the phenomenon of nitrate tolerance. Circ Res. 2005;97:618–28. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000184694.03262.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itoh Y, Takaoka R, Ohira M, Abe T, Tanahashi N, Suzuki N. Reactive oxygen species generated by mitochondrial injury in human brain microvessel endothelial cells. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2006;34:163–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]