Abstract

The authors report a case of spinal dural arteriovenous fistula (SDAVF) that is supplied by a lateral sacral artery. A 73-year-old male presented with gait disturbance that had developed 3 years ago. Spinal magnetic resonance imaging suggested a possible SDAVF. Selective spinal angiography including the vertebral arteries and pelvic vessels showed the SDAVF fed by left lateral sacral artery. The patient was subsequently treated with glue embolization. Three days after the embolization procedure, his gait disturbance was much improved.

Keywords: Spinal dural arteriovenous fistula (SDAVF), Lateral sacral artery, Spinal angiography, Embolization

INTRODUCTION

Spinal dural arteriovenous fistulae (SDAVFs) are rare; however, they are the most common vascular malformations of the spine and represent about 80% of spinal arteriovenous malformations10). The clinical signs and symptoms as well as the course of disease are sometimes disguising, so the final diagnosis is established relatively late after the initiation of diagnostic evaluation6). However, recent advances in selective angiography and embolization techniques made the early diagnosis and treatment of this disease possible. Therefore, severe neurologic deficits due to SDAVF can often be prevented. The pathophysiologic mechanism in SDAVF is a nonhemorrhagic venous hypertensive myelopathy, which leads to venous congestion and chronic hypoxia, and potentially to venous infarction and irreversible spinal cord lesion2,12,14). The fistula sites are most commonly in the thoracic and lumbosacral regions and commonly supplied by intercostal and lumbar arteries7,9,12,14). However, depending on the fistula location, arterial supply from branches of the thyrocervical, costocervical, middle sacral, external carotid, and vertebral arteries have been reported7,9). In this paper, we report a rare case of SDAVF supplied by a lateral sacral artery, which was successfully treated with endovascular embolization.

CASE REPORT

Clinical history and neurological examination

A 73-year-old male was admitted to our hospital with a 3-year history of gait disturbance. Also, he complained of bilateral leg pain that had developed five-months before the admission. On neurological examination, the patient was noted to have right leg weakness (motor grade 4/5), but the pinprick, light touch and vibration senses were intact and deep tendon reflexes were normoactive bilaterally. Babinski's sign and ankle clonus were not noted.

Radiologic findings

Spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed diffuse high signal lesion within the spinal cord from the level of the ninth thoracic vertebra to the conus medullaris on T2-weighted images and numerous flow voids over the ventral and dorsal surface of the spinal cord (Fig. 1), suggestive of a SDAVF. On day 3 after admission, selective digital subtraction angiography of bilateral vertebral, subclavian, radicular arteries below second thoracic vertebra, lumbar and common iliac arteries were performed. The angiograms demonstrated the SDAVF supplied by the lateral sacral branch of the left internal iliac artery (Fig. 2).

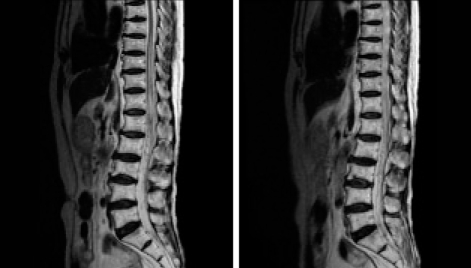

Fig. 1.

Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance images showing high signal intensity within the spinal cord from the level of ninth thoracic vertebra to the conus medullaris that are indicative of diffuse spinal cord swelling, and fine signal voids around the cord surface that are indicative of vascular structures.

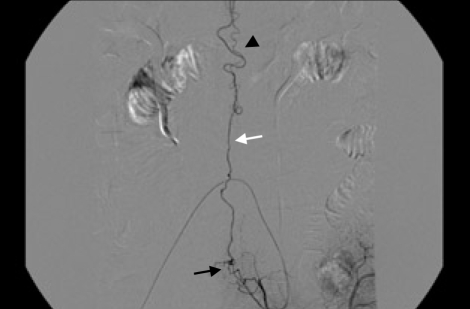

Fig. 2.

Selective angiography of left internal iliac artery demonstrates the spinal dural arteriovenous fistula (black arrow) with early venous drainage through sacral medullary vein (white arrow) leading to dilated perimedullary veins (arrowhead) around the spinal cord.

Endovascular treatment

The embolization therapy was performed urgently because the patient's leg weakness progressed rapidly to papaplegia. The procedures were performed in the operating room angiography suite under local anesthesia. Right femoral artery was punctured and a 6-Fr introducer sheath was inserted. First, diagnostic left internal iliac angiography was done using a 5-Fr Headhunter catheter (Cook, Bloomington, USA). SDAVF supplied by the left lateral sacral artery was seen. The Headhunter catheter could not be stabilized at the orifice of the left lateral sacral artery, so the catheter was exchanged with a Davis catheter (Cook, Bloomington, USA), which was well stabilized at the orifice. The lateral sacral artery was selected using an Excelsior SL-10 microcatheter (Boston Scientific, Watertown, USA). Selective digital subtraction angiography of the lateral sacral artery using the microcatheter also revealed the SDAVF. Under fluoroscopic guidance, embolization of the fistula was proceeded using 0.4 mL of 25% glue (N-butyl cyanoacrylate : ionized oil=1 : 3). After the embolization, no residual connection between the arterial and venous systems was visualized (Fig. 3). There was no complication. Three days after the embolization, his gait disturbance was much improved (motor grade 5/5). Two weeks after the embolization, he was able to walk without dragging his right leg. Follow-up spine MRI of the patient showed no flow voids over the surface of the spinal cord, although high signal intensity on T2-weighted images within the spinal cord from the level of the ninth thoracic vertebra to the conus medullaris was not yet disappeared (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

A : Left internal iliac angiography showing the lateral sacral artery (double arrows) supplying the arteriovenous fistula (arrow) in an oblique view. B : Left internal iliac angiography after embolization shows complete obliteration of the fistula.

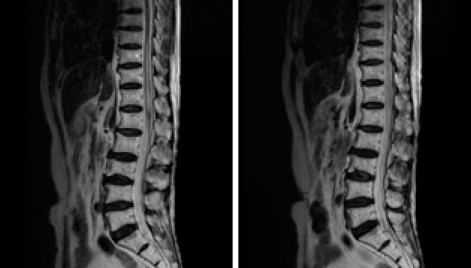

Fig. 4.

On follow-up evaluation, 2 weeks after the embolization therapy, spine MRI show no flow voids over the surface of the spinal cord, although high signal intensity on T2-weighted images within the spinal cord is not yet improved.

DISCUSSION

SDAVF is the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, constituting 80% of all spinal arteriovenous malformations10). This type of acquired vascular malformation is located most commonly in the thoracic and lumbosacral regions. According to the report of Nishio et al.11), at the time of their writing, 42 cases of SDAVFs arising from internal iliac arteries had been reported in the literature, including their case7,8,10,11,13).

SDAVF usually presents with progressive paraparesis, sensory deprivation of the lower extremity, and bowel and bladder dysfunction6,14). Behrens and Thron1) reported that, in 21 patients treated for SDAVF, the mean time from the onset of neurological dysfunction to diagnosis was 15.5 months (range, 2-60 months), and the clinical symptoms and signs were extremely variable. In our case, the time interval from onset of neurological dysfunction to diagnosis was 36 months.

An acute onset is reported in 5-18% of patients. If symptoms develop within minutes to hours they can mimic an anterior spinal artery syndrome. The sudden episodes mostly occur after exercise, prolonged standing and even singing, and may disappear after rest. Acute worsening of symptoms may also be related to changes in posture such as bending over; even eating has been related with worsening of symptoms4). In our patient, the acute paraplegia after spinal angiography was most likely caused by acutely increased venous pressure. This exacerbated venous engorgement, cord edema, and cord ischemia. This feature highlights the effect of acutely increased venous hypertension in a lesion whose pathogenesis involves chronically impaired or "marginal" venous drainage5).

The most important aspect in the management of SDAVF is that therapy for the lesion must be initiated immediately after diagnosis is conclusively made3,13,14). In our patient, the embolization therapy was performed soon after the diagnosis was made. Although the duration between the onset of neurological symptom and the definite diagnosis was 36 months, the motor dysfunction of the patient was not so severe. The fact that our patient's motor function was relatively preserved (motor grade 4/5) explains the excellent postoperative outcome.

There are some points to be discussed in the embolization therapy of SDAVF with supply from the lateral sacral artery as in our case. During the catheterization procedures, the guiding catheter courses from a site of femoral puncture, passing aortic bifurcation, to the contralateral internal iliac artery. So, the guiding and microcatheter are to have two or more acute turning angles, and this is thought to be the major difficulty to hinder the catheters to be positioned stable in the selected arterial orifice. In this point of view, the selection of appropriate type of catheter and suitable shaping of the catheter are very important point. In this case, we used a 5-Fr Headhunter catheter (Cook, Bloomington, USA) initially, but the catheter could not be stabilized at the orifice of the left lateral sacral artery, so the catheter was exchanged with a Davis catheter (Cook, Bloomington, USA), which was well stabilized at the orifice. In embolization therapy, it also must be taken into account that the long-term results of embolization are different according to which embolization material is used. Embolization with cyanoacrylate glue, used in our case, is equal to surgical obliteration in effectiveness, but the results of embolization for SDAVFs with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particle are disappointing because recanalization has been described in 30 to 70% of the cases7).

CONCLUSION

We report a rare case of SDAVF that supplied by the lateral sacral artery. If routine spinal angiography including bilateral intercostal and lumbar arteries is not diagnostic, lateral sacral arteries should be studied, because the feeding artery can be derived from them via the filum terminale.

References

- 1.Behrens S, Thron A. Long-term follow-up and outcome in patients treated for spinal dural arteriovenous fistula. J Neurol. 1999;246:181–185. doi: 10.1007/s004150050331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eskandar EN, Borges LF, Budzik RF, Jr, Putman CM, Ogilvy CS. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas : experience with endovascular and surgical therapy. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(2 Suppl):162–167. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.1.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurst RW, Grossman RI. Peripheral spinal cord hypointensity on T2-weighted MR images : a reliable imaging sign of venous hypertensive myelopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:781–786. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jellema K, Tijssen CC, van Gijn J. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas : a congestive myelopathy that initially mimics a peripheral nerve disorder. Brain. 2006;129:3150–3164. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khurana VG, Perez-Terzic CM, Petersen RC, Krauss WE. Singing paraplegia : a distinctive manifestation of a spinal dural arteriovenous fistula. Neurology. 2002;58:1279–1281. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.8.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch C. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistula. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19:69–75. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000200547.22292.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsen DW, Halbach VV, Teitelbaum GP, McDougall CG, Higashida RT, Dowd CF, et al. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas supplied by branches of the internal iliac arteries. Surg Neurol. 1995;43:35–40. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(95)80035-f. discussion 40-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merland JJ, Riche MC, Chiras J. Intraspinal extramedullary arteriovenous fistulae draining into the medullary veins. J Neuroradiol. 1980;7:271–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan MK, Marsh WR. Management of spinal dural arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:832–836. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.6.0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mourier KL, Gelbert F, Rey A, Assouline E, George B, Reizine D, et al. Spinal dural arteriovenous malformations with perimedullary drainage. Indications and results of surgery in 30 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1989;100:136–141. doi: 10.1007/BF01403601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishio A, Ohata K, Takami T, Nishikawa M, Hara M. Atypical spinal dural arteriovenous fistula with supply from the lateral sacral artery. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Brien WT, Schwartz ED, Hurst RW, Sinson G. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistula with supply from sacral arteries. Surg Neurol. 2001;56:175–176. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(01)00486-4. discussion 177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park KW, Rhim SC, Suh DC, Roh SW. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistula from lateral sacral artery. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2003;44:258–261. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2009.45.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaat TJ, Salzman KL, Stevens EA. Sacral origin of a spinal dural arteriovenous fistula : case report and review. Spine. 2002;27:893–897. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200204150-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]