Abstract

The bottom-up assembly of patterned arrays is an exciting and important area in current nanotechnology. Arrays can be engineered to serve as components in chips for a virtually inexhaustible list of applications ranging from disease diagnosis to ultra-high-density data storage. Phi29 motor dodecamer has been reported to form elegant multilayer tetragonal arrays. However, multilayer protein arrays are of limited use for nanotechnological applications which demand nanoreplica or coating technologies. The ability to produce a single layer array of biological structures with high replication fidelity represents a significant advance in the area of nanomimetics. In this paper, we report on the assembly of single layer sheets of reengineered phi29 motor dodecamer. A thin lipid monolayer was used to direct the assembly of massive sheets of single layer patterned arrays of the reengineered motor dodecamer. Uniform, clean and highly ordered arrays were constructed as shown by both transmission electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy imaging.

Keywords: bacteriophage phi29, portal vertex, dodecamer, single layer patterned arrays

The ability to synthesize patterned arrays in a controllable fashion is of extensive interest for nanotechnology.1−5 Most of the current micro- and nanofabrication approaches use a variety of robust materials to generate morphologies with typical geometrical shapes such as chip, pillars, bar, or pyramids. Superlattices have been fabricated by various physical or chemical methods including deposition,6−8 donor/receptor interaction,(9) self-assembly,10−13 complementation,14−16 colloidal crystallization,17−21 replica,(22) cross-linking,23,24 nanoimprint lithography,(25) or patterned etch pits.(26) The construction of lattices that mimic the structural complexity of biological structures would be very intriguing and challenging.

In nanotechnology, a nanomachine is a mechanical or electromechanical device with nanometer size dimensions.27,28 Considerable efforts have been focused on the research and development of nanomachines and their potential applications in medical related fields. One promising avenue is to construct synthetic nanomachines that mimic the powerful natural bionanomachines and to incorporate them into traditional nanotechnological applications.29,30 Living systems manufacture a large variety of nanomachines made of protein,(31) DNA,(32) and RNA(33) with atomic precision, including motors, arrays, pumps, membrane cores, and valves. The structural and conformational complexity of biological molecules brings about new avenues and challenges to experimental approaches at the bio/nano interface.1,4,33−36 For instance, fabrication of replica-molded biomaterials requires precise topographical patterning. Two-dimensional crystals of proteins have been reported growing on a lipid monolayer at an air−water interface by using Langmuir deposition or by spreading a protein solution at the liquid−air interface.1,37,38 Efficient and reproducible transfer of such 2D crystalline protein films onto solid substrates would have substantial implications in the design of nanotechnological devices. Similarly, protein adsorption on solid substrates with predictable self-assembly patterns is another valuable tool for nanopatterning. The use of DNA,39−42 RNA,5,43,44 and protein45−48 as building blocks in nanotechnology has an advantage over the chemical materials in their eligibility for site-directed modification and specific conjugation with defined stoichiometry. In addition, they can self-assemble and be connected directly to biological molecules. Self-assembly of molecules on a surface can be a simple, versatile, and high-volume production approach for the construction of biological arrays.5,40−44 The ability to replicate biological shapes with nanoscale precision could have profound implications in tissue engineering, cell scaffolding, drug delivery, sensors, imaging, nanotechnology, and nanomedicine.

One particularly attractive candidate found in the viral DNA-packaging machinery, from which both protein and RNA bionanocomponents may be harvested, is the Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage phi29 DNA-packaging motor.49−58 This powerful motor comprises a portal vertex—a 12-subunit gp10 (dodecamer protein, also called as connector),52,53 pRNA,(54) gp16, and ATP55−57—that provides the chemical energy required for DNA packaging. These components can be combined in vitro to assemble one of the most powerful nanomachines constructed to date.58,59

The class of dodecamer (connector) proteins which form varieties of portal vertex shares little sequence homology among different viruses, but the resulted portal vertex has considerable morphological similarity.60−63 Information from Cryo-EM(64) and X-ray crystallographic studies52,53,63,65 revealed the portal vertex is a 12-fold symmetric dodecamer with a truncated cone shape about 7.5 nm long and with a diameter of 6.8 nm at the narrow end (N-terminus) and 13.8 nm at the wide end (C-terminus). The central channel has a diameter of 3.6 nm. The wide end of the dodecamer is embedded in the procapsid shell, while the narrow end of the dodecamer, protruding out of the procapsid, is the foothold for pRNA binding.66,67

Previous work has shown that the wild-type dodecamer can be used to form arrays with a mixture of single, double, or multiple layered structures.47,68 Multilayer arrays could be easily produced from ordered aggregates of portal vertex. However, multilayer arrays are of limited use for nanotechnological applications such as replica, which demand uniform, single layer biomolecular arrays. It has been found that some multilayer crystals can be converted to single layer in solution over a period of a few weeks by gradually changing the salt concentration.(68) However, such a step is time-consuming and only generates small sheets as a mixture with single, double, and mutlilayers. Due to the thinness and frangibility, purification of the single layer from the mixture is almost impossible.

In this study, we demonstrate that we can easily produce huge two-dimensional single layer arrays of terminus-modified portal vertex using a lipid monolayer as template. The method is simple and reproducible.

Results and Discussion

Approaches to Redirect Formation of Multilayer Structures into Single Layer Patterned Arrays

The formation of multilayer arrays is driven by two distinct protein interaction mechanisms. First, horizontal side-by-side interactions between individual dodecamers allow for the extension and growth of a two-dimensional layer. Second, interactions between the narrow and the wide ends of dodecamer molecules promote the buildup of multiple layers vertically (1). To facilitate the formation of a single layer and prevent the continuous growth of multiple layers, a short peptide sequence was introduced either into the gp10 N- or C-terminus, located at the narrow and wide end of the dodecamer, respectively (1).

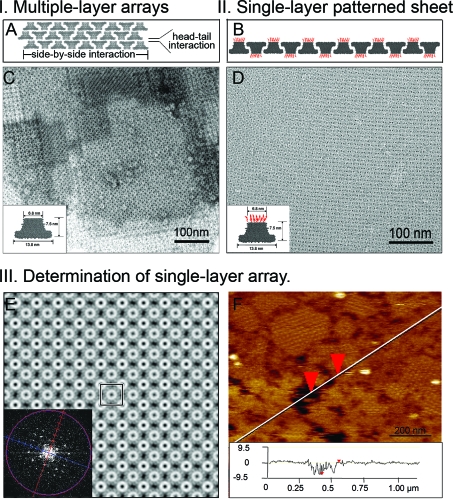

Figure 1.

Multilayer versus single layer sheet arrays of phi29 motor dodecamer. (A) Side view of a multiple layer dodecamer array showing the horizontal face-up and face-down arrangements and the vertical head-to-tail alignment which leads to multiple layers overlap. (B) Side view of a single layer dodecamer array displaying an alternating face-up and face-down arrangement. (C) Native phi29 motor dodecamer (inset) assembled into ordered multiple layer structures as shown by negative-stain electron micrograph. (D) The negative-stain electron micrograph of reengineered phi29 motor dodecamer (inset) arrays shows that a single layer sheet was formed. (E) Projection density map of the single layer of motor dodecamers and the Fourier transform (inset). The unit cell is rectangular, with a lattice constant of ∼20 nm. The alternate orientations of the dodecamer can be observed. (F) AFM image of N-strep dodecamer arrays and a line scan across crystalline area with lattice defects (inset). The height difference between the top dodecamer layer and mica surface is ∼7.5 nm, which corresponds to a single dodecamer layer.

Strep-Tag Extension of the C- or N-Terminus Favors the Assembly of Dodecamer Sheets in Solution

The phi29 portal vertex is a truncated cone-shaped structure having the gp10 N- and C-terminus located at the narrow and wide end, respectively. Fusion of a simple 22 amino acid Strep-tag to the N-terminus of the portal vertex did not interfere with the assembly of the quaternary dodecamer structure. After expression in E. coli cells, the recombinant gp10 assembled into dodecamer particles with similar shape to the native portal vertex as shown by TEM (data not shown). Additionally, the Strep-tag extension facilitates purification of the dodecamer protein with high yield and homogeneity. It has been previously reported that two-dimensional dodecamer arrays could be grown in solution from concentrated native dodecamer (connector) solution following several weeks of incubation under a defined ionic strength gradient of the buffer.47,68 However, without this precise chemical treatment, the native portal vertex has the tendency to form patches of multiple layers. 1 illustrates a multiple layer structure of native dodecamers. The individual dodecamers exhibit both lateral side-by-side and vertical head-to-tail interactions. We have used a reengineered motor dodecamer for the self-assembly of single layer dodecamer sheets (schematically shown in 1). Arrays constructed from both native (1 inset) and reengineered dodecamer (1 inset) and imaged by TEM are shown in 1. As previously reported, the unmodified dodecamer generated multiple overlapping layers with tetragonal symmetry (1). The different shades of gray represent the different layers formed and overlapping. The extent to which different layers overlap cannot be controlled, and thus it is difficult to reproduce the same multilayer structure. Interestingly, the reengineered dodecamer with the added N-terminal extension self-assembled into huge flat sheets that piled into three-dimensional stacks (1). Such stacks are different from 3D crystals, of which the stacks are governed by specific interaction between different layers. However, in these stacks, the sheets arrange in random orientation (2), suggesting that each sheet formed or grew independently. It is understandable that, without a support, the fragile sheet of the thin layer could not stand alone (see next section for formation of single layer sheets on supporting lipid monolayer). From the EM images, it appeared that the size of the center channel was smaller (compare 1C and D). This is possibly due to partial filling-up of the edge of the channel by the extended peptide at the N-terminus.

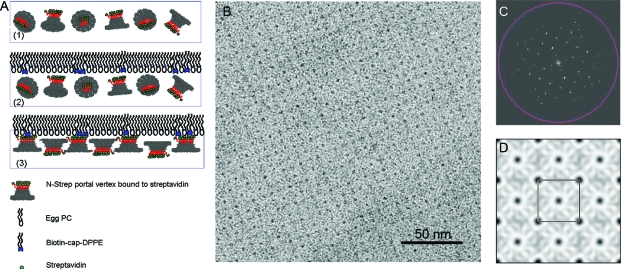

Figure 2.

Negative-stain electron micrographs and corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) of two-layer patterned sheets of N-strep dodecamer. (A) Self-assembled huge flat sheets piled into 3D stacks. (B) Representative fast Fourier transformation. (C) The red and blue circles in the image suggested two layers sheets slightly arranged in different angle, suggesting that each sheet formed or grew independently and stacked together.

The arrangement of the individual dodecamers was analyzed using statistical classification and averaging (1 inset). The truncated cone structure of a single dodecamer enables us to distinguish between the face-up and face-down orientations. The corresponding projection density map shows the alternating face-up and face-down arrangement of dodecamers (1). The unit cell is a square with a dimension of ∼20 nm. Due to the alternating orientations of the motor, the central face-up dodecamer displays a larger diameter (corresponding to the wider C-terminal end) than the surrounding face-down dodecamers located in each corner of the square. The alternative face-up and -down data agree with the previous studies on EM imaging, X-ray crystallography, topological analysis, structure projection of the 2D crystals, 3D reconstruction, and computer modeling of the dodecamers.47,64,65,69 The individual 12 subunits can also be observed. Formation of single layer arrays was further confirmed by AFM imaging. Freshly cleaved muscovite mica was used as an alternative substrate. 1 shows a typical AFM image of crystalline N-strep dodecamer single layers imaged in tapping mode in liquid. Patches of crystalline areas with submicrometer size can be observed. The large scan image shows a high surface coverage of the protein layer with only small imperfections. A line scan across the single layer sample (1 inset) indicates that the single layer thickness is ∼7.5 nm, which is in excellent agreement with the height of the motor dodecamer determined from the three-dimensional crystal structures.(53) Similar single layer arrays were also produced from dodecamers of gp10 with a peptide extension at the C-terminus which serves as a barrier for the vertical interactions (data not shown).

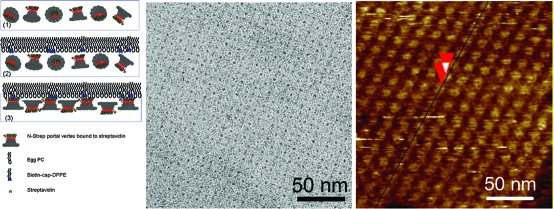

Formation of Single Layer Dodecamer Arrays Directed by Lipid Monolayers

Nanotechnological applications of arrays require the assembly of homogeneous broad and wide-ranging flat sheets. Due to the flexible and fragile nature of proteins, it would be desirable to employ a biological template to direct the assembly of single layer arrays. To explore this possibility, thin layers of biotinylated lipid mixtures were used to direct the assembly of N-strep dodecamers which carry a Strep-tag at the N-terminus of each gp10 subunit. The N-strep dodecamer was preincubated with streptavidin before the lipids were spread. Arrays were grown in situ on lipid monolayers at the air−water interface and then transferred on carbon-coated TEM grids. Saturated dipalmitoyl fatty acid chains (C16) of biotinyl dap DPPE were mixed with unsaturated phosphatidylcholine fatty acids chains of egg PC (C18) in a 1:3 (w/w) ratio and spread at the liquid−air interface. Dodecamers were attached to the lipid surface via specific biotin−streptavidin interactions (3). Initially, the N-strep -tagged dodecamer bound to streptavidin is randomly oriented in solution. After the lipid mixture containing the biotinylated lipid is applied on the water surface, the N-strep dodecamer/streptavidin complex binds specifically to the biotinylated lipid. The arrangement of the individual dodecamers is dictated by the intermolecular protein contacts and protein−surface interactions. The distance between subsequent dodecamers is governed by the intrinsic nature of the protein which exhibits strong side-by-side interactions. Protein−protein, protein−lipid, and lipid−lipid interactions contribute to the single layer arrangement dodecamers in the lipid matrix. The unsaturated diluting lipid egg PC provides fluidity and flexibility to the lipid monolayer. The bound protein is carried by the biotinylated lipid through the lipid matrix which confers to the translational and rotational freedom required for the nucleation and growth of crystalline patches. After overnight incubation, the single layer was transferred to a hydrophobic grid and imaged by TEM (3). The Fourier transform and the corresponding projection density map of the negatively stained electron micrograph (3C and D, respectively) revealed tetragonally packed 2D dodecamer crystals with a unit cell size of ∼18 × 18 nm2. The unit cell dimensions are in close agreement with those previously measured on two-dimensional phi29 dodecamer crystals by TEM.(68)

Figure 3.

Lipid-directed formation of single layer dodecamer arrays. (A) Schematic illustration of experimental approaches. (1) Streptavidin/N-strep dodecamer solution is placed in a Teflon well; (2) biotinylated lipids DPPE and helper lipids egg PC were spread at the air−water interface to attract dodecamers to the surface of the liquid; (3) dodecamers bound to the lipid via specific biotin−streptavidin interactions. (B) Negative-stain TEM image of a single layer array produced with the aid of a lipid monolayer. (C) Fourier transforms and (D) corresponding Fourier projection maps of lipid-directed N-strep dodecamer arrays.

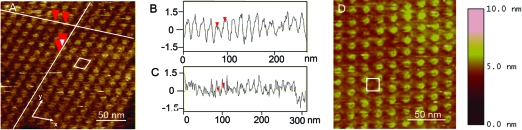

Single Layer Dodecamer Arrays Visualized by AFM

Hydrophilic bare mica was used as alternative surface for the assembly and adsorption of single layers of the reengineered dodecamer with either N- and C-strep modified dodecamers. High-resolution images of the patterned surface are shown in 4. The N-strep dodecamers self-assembled into a parallelogram lattice (4). Cross-sections along the x (4) and y (4) directions of the crystalline areas indicated unit cell dimensions of ∼16 and ∼13 nm in the x and y directions, respectively. The angle between the x and y axis has been calculated to be ∼71°. Even though the tetragonal arrangement previously observed was maintained, the slightly different and unequal unit cell dimensions suggest that the packaging unit of this type of crystal might be slightly different from that of the lipid-directed N-strep 2D crystal. The crystal lattice in 4 is different from those in 1−3 concerning the angle of the pattern. While asking whether the difference observed in the lattices was the consequence directly related to the mutation of the protein is very intriguing, still little is known. A rectangular lattice with unit cell dimensions of 18 × 18 nm2 has been observed for the C-strep mutant. The dodecamer orientation in the self-assembled layer on the mica surface was similar to that in the three-dimensional crystal and generated face-up and face-down arrangements. While occasionally the low force applied for imaging was sufficient to image what appeared to be the narrow ends of the dodecamer, most of the time we could only visualize the wide dodecamer domains due to the nature of tip−sample interactions in AFM imaging.

Figure 4.

High magnification AFM images of self-assembled arrays of reengineered motor dodecamers. (A) Tetragonal arrays of N-strep dodecamer. (B and C) Cross-sections along the axes of the two-dimensional array. The unit cell is a parallelogram with cell dimensions of 16 nm × 13 nm. (D) Tetragonal arrays of C-strep dodecamer. The unit cell is rectangular with a lattice constant of ∼18 nm.

Mica has more than 10 different phases concerning the surface lattice. The lattices of mica and dodecamer are of a different order of magnitude, in which mica is calculated about 6 Å compared to the protein with a unit cell in the regime of about 16–18 nm. In this AFM imaging, it is not clear whether the mica surface lattice played a role here in organizing the pattern of the proteins array, and whether the mica surface lattice and the protein crystal lattice are relevant or in a good match. However, previous studies have shown that the purified native dodecamer self-assembled into tetragonal arrays in solution without the mica support,(47) guiding of these nanoparticles by the mica surface lattice to form the pattern in this report might not be necessary. Instead, the pattern of the lattice might have been dictated by the intrinsic property of the mutant dodecamer structure.

Conclusions

A short Strep-tag sequence modification of the N- or C-terminus of the phi29 portal vertex facilitates its purification with high yield and homogeneity. The modification did not interfere with the dodecamer assembly and function. The mutant protein exhibited favorable lateral interactions and led to the formation of large dodecamer sheets. In solution, the 2D dodecamer arrays interacted vertically to pile up into 3D stacks of protein sheets as revealed by TEM imaging. Large single layer sheets of highly ordered array have been constructed using a supporting lipid monolayer.

Methods

Reengineering of Phi29 Motor Dodecamer

Two clones of portal vertex protein were engineered by attaching a Strep-tag II (WSHPQFER) to either the N-terminus or the C-terminus of each gp10 subunit. Cloning methods of the N-strep and C-strep dodecamer have been described previously.(70)

Purification of the Reengineered Dodecamer

A column packed with 1 mL of Strep-Tactin sepharose resin (IBA, St. Louis, MO) was equilibrated with 10 column bed volumes of buffer W (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 15% glycerol). After lysis of E. coli cells containing the reengineered gp10, the lysate was clarified and the supernatant was loaded onto the column, followed by washing with buffer W, the protein was eluted with buffer E (500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM desthiobiotin, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 15% glycerol).

Assembly of Dodecamer Arrays

Two approaches were used to construct dodecamer arrays: (1) self-assembly from concentrated solutions of purified native and N-strep or C-Strep motor dodecamer and (2) lipid-directed assembly of single layer dodecamer arrays. The schematic illustrations of multilayer arrays or single layer patterned sheets are shown in 1.

Self-Assembled Dodecamer Arrays

Concentrated solutions of purified, reengineered C- and N-strep dodecamer in buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.02% sodium azide 15% glycerol, pH 8.0) were stored at −20 °C. Protein solutions dialyzed and diluted if necessary to a stock of 1 mg/mL were kept at 4 °C for a few days and used for the construction of two-dimensional arrays. A 1:35 dilution of the protein stock solution in imaging buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM KCl) was applied on freshly cleaved mica. The sample was placed in a humidified, closed Petri dish to avoid drying out. Following 2 h incubation at room temperature, the sample was rinsed with imaging buffer and kept at 4 °C overnight. The sample was allowed to reach room temperature prior to AFM imaging.

Lipid-Directed Single Layer Dodecamer Arrays

Two-dimensional dodecamer arrays were grown at the liquid−lipid interface as previously reported by Sun et al.71,72 The N-strep dodecamer at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL was incubated in buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2, pH 8) at room temperature with a 6-fold excess of streptavidin (Sigma). A volume of 15 μL of the N-strep dodecamer bound to streptavidin was placed into a custom-designed Teflon well of 4 mm in width and 1 mm in depth. The lipid mixture of 30 μg/mL biotin-cap-DPPE and 90 μg/mL egg phosphatidylcholine (Avanti Lipids, AL) was prepared in chloroform, and 0.3 μL of the lipid mixture was layered on top of the protein solution and incubated overnight at 4 °C in a humidified chamber.

Imaging of Single Layer Arrays by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Samples were prepared by applying the protein stock solution on hydrophilic glow discharged carbon grids that were negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate (UA) or 2% (w/v) ammonium molybdate. The two-dimensional arrays grown on the lipid matrix were transferred to a hydrophobic carbon-coated copper grid without glow-discharged, washed with distilled water, and negatively stained with an aqueous solution of 1% UA and imaged by TEM. The images were acquired at 45000× magnifications on a Philips CM12 TEM operated at 80 kV acceleration voltages and equipped with a CCD camera (Gatan, Inc., PA). The reengineered phi29 motor dodecamer arrays were applied on glow-discharged carbon-coated grids, washed with distilled water, and negatively stained 2% ammonium molybdate. The grids were transferred into a JEOL-2100F TEM operated at 120 kV, and the images were acquired at 40000× magnification on a 4k × 4k CCD camera (TVIPS, Germany). Image processing, structural determination, and three-dimensional reconstruction (3D) were carried out by the electron crystallographic method using CRISP software package.(73) The two-dimensional (2D) projection map of the dodecamer array was generated using the EMAN software as described elsewhere.(74)

Imaging of Single Layer Arrays by AFM

Special care has been taken to maintain the sample under buffer at all times. Samples were allowed to reach room temperature before being imaged by AFM. The self-assembled dodecamer arrays were imaged in liquid in tapping mode using a Nanoscope III multimode instrument (Veeco/Digital Instruments, Santa Barbara, California) equipped with a 130 μm scanner (J scanner). Tapping in liquid was performed in a buffer droplet in a tapping-mode liquid cell without an O-ring seal. Scanning was performed using narrow-legged cantilevers (OMCL-TR400PSA, Olympus Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with oxide sharpened Si3N4 tips. The V-shaped cantilevers had a length of 100 μm and a nominal spring constant of 80 pN/nm. Cantilevers were driven at the resonance frequencies of 8.4 ± 0.5 kHz with piezo drive amplitudes of 50−100 mV, resulting in cantilever amplitudes of ∼0.5 V. Scanning was performed at speeds between 1 and 2 Hz. Image processing (2nd order flattening) and data analysis was done with the Nanoscope software version 5.12r5.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Green from University of California at Davis for his technical assistance and valuable comments, as well as the preparation of 1 and 2. This work was supported by PN2 EY018230 from NIH Nanomedicine Development Center for Phi29 DNA Packaging Motor for Nanomedicine through NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Moll D.; Huber C.; Schlegel B.; Pum D.; Sleytr U. B.; Sara M. S-Layer-Streptavidin Fusion Proteins as Template for Nanopatterned Molecular Arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 14646–14651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldaye F. A.; Palmer A. L.; Sleiman H. F. Assembling Materials with DNA as the Guide. Science 2008, 321, 1795–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubrich D.; Bath J.; Turberfield A. J. Templated Self-Assembly of Wedge-Shaped DNA Arrays. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 8530–8534. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman N. C.; Belcher A. M. Emulating Biology: Building Nanostructures from the Bottom Up. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 6451–6455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu D.; Moll D.; Deng Z.; Mao C.; Guo P. Bottom-Up Assembly of RNA Arrays and Superstructures as Potential Parts in Nanotechnology. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 1717–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin V. L.; Goldstein A. N.; Alivisatos A. P. Semiconductor Nanocrystals Covalently Bound to Metal Surfaces with Self-Assembled Monolayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 5221–5230. [Google Scholar]

- Dabbousi B. O.; Murray C. B.; Rubner M. F.; Bawendi M. G. Langmuir−Blodgett Manipulation of Size Selected CdSe Nanocrystals. Chem. Mater. 1994, 6, 216–219. [Google Scholar]

- Whetten R. L.; Khoury J. T.; Alvarez M. M.; Murthy S.; Vezmar I.; Wang Z. L.; Stephens P. W.; Cleveland C. L.; Luedtke W. D.; Landman U. Nanocrystal Gold Molecules. Adv. Mater. 1996, 8, 428–433. [Google Scholar]

- Otero R.; Ecija D.; Fernandez G.; Gallego J. M.; Sanchez L.; Martin N.; Miranda R. An Organic Donor/Acceptor Lateral Superlattice at the Nanoscale. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 2602–2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng N. F.; Bu X. H.; Feng P. Y. Self-Assembly of Novel Dye Molecules and [Cd8(Sph)12]4+ Cubic Clusters into Three-Dimensional Photoluminescent Superlattice. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 9688–9689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q.; Ding Y.; Wang Z. L.; Zhang Z. J. Formation of Orientation-Ordered Superlattices of Magnetite Magnetic Nanocrystals from Shape-Segregated Self-Assemblies. J. Phy. Chem. B 2006, 110, 25547–25550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. W.; Mao C.; Flynn C. E.; Belcher A. M. Ordering of Quantum Dots Using Genetically Engineered Viruses. Science 2002, 296, 892–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin E.; Peet C.; Stubbs G.; Culver J. N.; Mann S. Organization of Metallic Nanoparticles Using Tobacco Mosaic Virus Templates. Nano Lett. 2003, 3, 413–417. [Google Scholar]

- Mirkin C. A.; Letsinger R. L.; Mucic R. C.; Storhoff J. J. A DNA Based Method for Rationally Assembling Nanoparticles into Macroscopic Materials. Nature 1996, 382, 607–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alivisatos A. P.; Johnsson K. P.; Peng X.; Wilson T. E.; Loweth C. J.; Bruchez M. P. Jr.; Schultz P. G. Organization of Nanocrystal Molecules Using DNA. Nature 1996, 382, 609–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbindyo J. K. N.; Reiss B. D.; Martin B. R.; Keating C. D.; Natan M. J.; Mallouk T. E. DNA-Directed Assembly of Gold Nanowires on Complementary Surfaces. Adv. Mater. 2001, 13, 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- vanBlaaderen A.; Ruel R.; Wiltzius P. Template-Directed Colloidal Crystallization. Nature 1997, 385, 321–324. [Google Scholar]

- Vossmeyer T.; et al. A Double Diamond Superlattice Built Up of Cd17S4(SCH2CH2OH)26 Clusters. Science 1995, 267, 1476–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motte L.; Billoudet F.; Lacaze E.; Pileni M. Self-Organization of Size-Selected Nanoparticles into Three Dimensional Superlattices. Adv. Mater. 1996, 8, 1018–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. B.; Kagan C. R.; Bawendi M. G. Self-Organization of Cdse Nanocrystals into 3-Dimensional Quantum Dot Super Lattices. Science 1995, 270, 1335–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Nykypanchuk D.; Maye M. M.; van der Lelie D.; Gang O. DNA-Guided Crystallization of Colloidal Nanoparticles. Nature 2008, 451, 549–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates B. D.; Xu Q.; Stewart M.; Ryan D.; Willson C. G.; Whitesides G. M. New Approaches to Nanofabrication: Molding, Printing, and Other Techniques. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1171–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brust M.; Bethall D.; Schiffrin D. J.; Kiely C. J. Novel Gold Dithiol Nanonetworks with Non-Metallic Electronic Properties. Adv. Mater. 1995, 7, 795–797. [Google Scholar]

- Andres R. P.; Bielefeld J. D.; Henderson J. I.; Janes D. B.; Kolagunta V. R.; Kubiak C. P.; Mahoney W. J.; Osifchin R. G. Self-Assembly of a 2-Dimensional Superlattice of Molecularly Linked Metal Clusters. Science 1996, 273, 1690–1693. [Google Scholar]

- Jung G. Y.; Johnston-Halperin E.; Wu W.; Yu Z. N.; Wang S. Y.; Tong W. M.; Li Z. Y.; Green J. E.; Sheriff B. A.; Boukai A.; et al. Circuit Fabrication at 17 nm Half-Pitch by Nanoimprint Lithography. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath J. R.; Williams R. S.; Shiang J. J.; Wind S. J.; Chu J.; DEmic C.; Chen W.; Stanis C. L.; Bucchignano J. J. Spatially Confined Chemistry: Fabrication of Ge Quantum Dot Arrays. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 3144–3149. [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y.; Lieber C. M. Functional Nanoscale Electronic Devices Assembled Using Silicon Nanowire Building Blocks. Science 2001, 291, 851–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craighead H. G. Nanoelectromechanical Systems. Science 2000, 290, 1532–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriev D. N.; Moll W.; Hall J.; Guo P. Bionanomotors. Encycl. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2003, 1, 361–374. [Google Scholar]

- Hess H.; Vogel V. Molecular Shuttles Based on Motor Proteins: Active Transport in Synthetic Environments. J. Biotechnol. 2001, 82, 67–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sára M.; Pum D.; Schuster B.; Sleytr U. B. S-Layers as Patterning Elements for Application in Nanobiotechnology. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2005, 5, 1939–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z.; Lee S. H.; Mao C. DNA as Nanoscale Building Blocks. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2005, 5, 1954–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P. RNA Nanotechnology: Engineering, Assembly and Applications in Detection, Gene Delivery and Therapy. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2005, 5, 1964–1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channon K.; Bromley E. H. C.; Woolfson D. N. Synthetic Biology through Biomolecular Design and Engineering. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008, 18, 491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulijn R. V.; Smith A. M. Designing Peptide Based Nanomaterials. Chem Soc Rev. 2008, 37, 664–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz E.; Willner I. Integrated Nanoparticle-Biomolecule Hybrid Systems: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 6042–6108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y. N. C.; Schrock R. R.; Cohen R. E. Synthesis of Single Silver Nanoclusters within Spherical Microdomains in Block Copolymer Films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 7295–7296. [Google Scholar]

- Sleytr U. B.; Sara M. Bacterial and Archaeal S-Layer Proteins: Structure-Function Relationships and Their Biotechnological Applications. Trends Biotechnol. 1997, 15, 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao C.; LaBean T. H.; Relf J. H.; Seeman N. C. Logical Computation Using Algorithmic Self-Assembly of DNA Triple-Crossover Molecules. Nature 2000, 407, 493–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothemund P. W. K. Folding DNA to Create Nanoscale Shapes and Patterns. Nature 2006, 440, 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldkamp U.; Niemeyer C. M. Rational Design of DNA Nanoarchitectures. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 1856–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Su M.; He Y.; Zhao X.; Fang P. A.; Ribbe A. E.; Jiang W.; Mao C. D. Conformational Flexibility Facilitates Self-Assembly of Complex DNA Nanostructures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 10665–10669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu D.; Huang L.; Hoeprich S.; Guo P. Construction of Phi29 DNA-Packaging RNA (pRNA) Monomers, Dimers and Trimers with Variable Sizes and Shapes as Potential Parts for Nano-Devices. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2003, 3, 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonin K. A.; Cieply D. J.; Leontis N. B. Specific RNA Self-Assembly with Minimal Paranemic Motifs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 93–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sara M.; Sleytr U. B. S-Layer Proteins. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 859–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida M.; Klem M. T.; Allen M.; Suci P.; Flenniken M.; Gillitzer E.; Varpness Z.; Liepold L. O.; Young M.; Douglas T. Biological Containers: Protein Cages as Multifunctional Nanoplatforms. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 1025–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y; Blocker F; Xiao F Guo P Construction and 3-D Computer Modeling of Connector Arrays with Tetragonal to Decagonal Transition Induced by pRNA of Phi29 DNA-Packaging Motor. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2005, 5, 856–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wargacki S. P.; Pate B.; Vaia R. A. Fabrication of 2d Ordered Films of Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV): Processing Morphology Correlations for Convective Assembly. Langmuir 2008, 24, 5439–5444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J. A.; Mendez E.; Salas M. Cloning, Nucleotide-Sequence and High-Level Expression of the Gene Coding for the Connector Protein of Bacillus subtilis Phage-Phi-29. Gene 1984, 30, 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P. X.; Lee T. J. Viral Nanomotors for Packaging of dsDNA and dsRNA. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 64, 886–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meifer W. J. J.; Horcajadas J. A.; Salas M. Phi29 Family of Phages. Microbiol. Mol. Biol Rev. 2001, 65, 261–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A. A.; Leiman P. G.; Tao Y.; He Y.; Badasso M. O.; Jardine P. J.; Anderson D. L.; Rossman M. G. Structure Determination of the Head-Tail Connector of Bacteriophage Phi29. Acta Crystallogr. 2001, D57, 1260–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guasch A.; Pous J.; Ibarra B.; Gomis-Ruth F. X.; Valpuesta J. M.; Sousa N.; Carrascosa J. L.; Coll M. Detailed Architecture of A DNA Translocating Machine: the High-Resolution Structure of the Bacteriophage Phi29 Connector Particle. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 315, 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P.; Erickson S.; Anderson D. A Small Viral RNA is Required for In Vitro Packaging of Bacteriophage Phi29 DNA. Science 1987, 236, 690–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P.; Peterson C.; Anderson D. Prohead and DNA-Gp3-Dependent ATPase Activity of the DNA Packaging Protein Gp16 of Bacteriophage ϕ29. J. Mol. Biol. 1987, 197, 229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu D.; Guo P. Only One pRNA Hexamer but Multiple Copies of The DNA-Packaging Protein Gp16 are Needed for the Motor to Package Bacterial Virus Phi29 Genomic DNA. Virology 2003, 309, 108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. J.; Guo P. Interaction of Gp16 with pRNA and DNA for Genome Packaging by the Motor of Bacterial Virus Phi29. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 356, 589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P.; Grimes S.; Anderson D. A Defined System for In Vitro Packaging of DNA-Gp3 of the Bacillus subtilis Bacteriophage Phi29. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1986, 83, 3505–3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. E.; Tans S. J.; Smith S. B.; Grimes S.; Anderson D. L.; Bustamante C. The Bacteriophage Phi29 Portal Motor can Package DNA Against a Large Internal Force. Nature 2001, 413, 748–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppler K.; Wyckoff E.; Goates J.; Parr R.; Casjens S. Nucleotide-Sequence of the Bacteriophage-P22 Genes Required for DNA Packaging. Virology 1991, 183, 519–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valpuesta J. M.; Sousa N.; Barthelemy I.; Fernandez J. J.; Fujisawa H.; Ibarra B.; Carrascosa J. L. Structural Analysis of the Bacteriophage T3 Head-To-Tail Connector. J. Struct. Biol. 2000, 131, 146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driedonks R. A.; Engel A.; tenHeggeler B.; van Driel R. Gene 20 Product of Bacteriophage T4: Its Purification and Structure. J. Mol. Biol. 1981, 152, 641–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guasch A.; Pous J.; Parraga A.; Valpuesta J. M.; Carrascosa J. L.; Coll M. Crystallographic Analysis Reveals the 12-Fold Symmetry of the Bacteriophage Phi29 Connector Particle. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 281, 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valpuesta J. M.; Fernandez J. J.; Carazo J. M.; Carrascosa J. L. The Three-Dimensional Structure of a DNA Translocating Machine at 10 Å Resolution. Structure 1999, 7, 289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badasso M. O.; Leiman P. G.; Tao Y.; He Y.; Ohlendorf D. H.; Rossmann M. G.; Anderson D. Purification, Crystallization and Initial X-Ray Analysis of the Head- Tail Connector of Bacteriophage Phi29. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D 2000, 56, 1187–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F.; Moll D.; Guo S.; Guo P. Binding of pRNA to the N-Terminal 14 Amino Acids of Connector Protein of Bacterial Phage Phi29. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 2640–2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F.; Zhang H.; Guo P. Novel Mechanism of Hexamer Ring Assembly in Protein/RNA Interactions Revealed by Single Molecule Imaging. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 6620–6632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carazo J. M.; Donate L. E.; Herranz L.; Secilla J. P.; Carrascosa J. L. Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of The Connector of Bacteriophage ϕ29 at 1.8 nm Resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1986, 192, 853–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez J.; Santisteban A.; Carazo J. M.; Carrascosa J. L. Computer Graphic Display Method for Visualizing Three-Dimensional Biological Structures. Science 1986, 232, 1113–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y.; Xiao F.; Guo P. N- or C- Terminal Alterations of Motor Protein Gp10 of Bacterial Virus Phi29 on Procapsid Assembly, pRNA Binding and DNA Packaging. Nanomedicine 2008, 4, 8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.; DuFort C.; Daniel M. C.; Murali A.; Chen C.; Gopinath K.; Stein B.; De M.; Rotello V. M.; Holzenburg A.; et al. Core-Controlled Polymorphism in Virus-Like Particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007, 104, 1354–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J. C.; Duffy K. E.; Ranjith-Kumar C. T.; Xiong J.; Lamb R. J.; Santos J.; Masarapu H.; Cunningham M.; Holzenburg A.; Sarisky R. T.; et al. Structural and Functional Analyses of the Human Toll-Like Receptor 3—Role of Glycosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 11144–11151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovmoller S. CRISP-Crystallographic Image Processing on a Personal Computer. Ultramicroscopy 1992, 40, 181–182. [Google Scholar]

- Ludtke S. J.; Baldwin P. R.; Chiu W. EMAN: Semiautomated Software for High-Resolution Single-Particle Reconstructions. J. Struct. Biol. 1999, 128, 82–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]