Abstract

Changes in gravitational force such as that experienced by astronauts during space flight induce a redistribution of fluids from the caudad to the cephalad portion of the body together with an elimination of normal head-to-foot hydrostatic pressure gradients. To assess brain gene profile changes associated with microgravity and fluid shift, a large-scale analysis of mRNA expression levels was performed in the brains of 2-week control and hindlimb-unloaded (HU) mice using cDNA microarrays. Although to different extents, all functional categories displayed significantly regulated genes indicating that considerable transcriptomic alterations are induced by HU. Interestingly, the TIC class (transport of small molecules and ions into the cells) had the highest percentage of up-regulated genes, while the most down-regulated genes were those of the JAE class (cell junction, adhesion, extracellular matrix). TIC genes comprised 16% of those whose expression was altered, including sodium channel, nonvoltage-gated 1 beta (Scnn1b), glutamate receptor (Grin1), voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (Vdac1), calcium channel beta 3 subunit (Cacnb3) and others. The analysis performed by Gene-MAPP revealed several altered protein classes and functional pathways such as blood coagulation and immune response, learning and memory, ion channels and cell junction. In particular, data indicate that HU causes an alteration in hemostasis which resolves in a shift toward a more hyper-coagulative state with an increased risk of venous thrombosis. Furthermore, HU treatment seems to impact on key steps of synaptic plasticity and learning processes.

Keywords: Microgravity, Hindlimb-unloaded, cDNA microarray, Brain, Space flight, Gravitational force, Microgravitational adaptations

Introduction

Gravity is an essential force that influences many life functions and has played a major role in the evolution of all terrestrial life. Therefore, changes in gravitational force are expected to affect many aspects of an organism’s physiology. Exposure to reduced gravity such as that experienced by astronauts during space flight induces a redistribution of blood and fluid from the caudad to the cephalad portion of the body and elimination of the head-to-foot hydrostatic pressure gradient (De Santo et al. 2001). Redistribution involves approximately 2 l of blood and fluid leading in astronauts to the so-called puffy faces and bird legs. In addition, symptoms such as headache and feeling of stuffiness in the nose and throat are frequently experienced by astronauts. Some of these symptoms are thought to be related to volume changes in the cerebrospinal fluid compartment (CSF) and may be the consequence of microgravitational adaptations of cerebral fluids (Fishman 1992).

The tail-suspended hindlimb-unloaded (HU) rat is widely used to study microgravity-induced alterations related to fluid redistribution in skeletal muscle (Frigeri et al. 2001) as well as volume changes in the CSF compartment and brain. This model induces cephalic fluid shift and postural muscle unloading (Hargens et al. 1984), thus generating fluid redistribution and balance resulting in fluid accumulation in atrophied muscle (Convertino et al. 1989). If prolonged for several days the fluid shift has been shown to alter the expression of certain genes in both animal and plant cells (Durzan et al. 1998; Yoshioka et al. 2001). Studies have been performed to analyze the adaptation of osteoblasts, blood cells and immune system (Nose and Shibanuma 1994; Hughes-Fulford and Lewis 1996 Lewis and Hughes-Fulford 2000) under hypergravity conditions. Regarding the brain, few studies have been performed. The effect of hypergravity has been studied in mice after rotation in a centrifuge apparatus, and the expression of genes in the hippocampus was found to be significantly modulated (Del Signore et al. 2004) including those involved in spatial learning (Cavallaro et al. 2002). In other studies it has been shown that space flight or exposure to hypergravity conditions affect the vestibular system in rats (Pompeiano et al. 2004; Uno et al. 2002) and the vestibular reflex in humans (Young 1995). Hypergravity can also affect synaptic contacts, since in fish a significant synaptic ultrastructural alteration after exposure to hypergravity has been reported (Rahmann et al. 1992).

In microgravity conditions, previous studies have reported changes in rat cortical circuits during brain development (DeFelipe et al. 2002) and in the overall density of dendritic spines in the sensorimotor cortex of adult rats (Belichenko 1998). More recently, a proteomic analysis of hippocampus of HU mice revealed changes in structural proteins coupled with the loss of proteins involved in cell metabolism (Sarkar et al. 2006). Furthermore, a similar analysis performed in hypothalamus revealed alteration of biomarkers of oxidative stress indicating vulnerability of the hypothalamus to the stress generated by microgravity (Sarkar et al. 2008).

All these studies suggest that changes in gravitational force may affect several aspects of brain function. Therefore, in order to obtain an overall view of the gene alterations occurring in the brain and to determine functional and structural pathways that are specifically affected by gravity changes, we have performed a large-scale analysis of mRNA expression levels of approximately 4,800 well-annotated distinct unigenes using cDNA microarray technology in the brains of 2-week hindlimb suspended mice.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57Bl6 J adult male mice, aged approximately 5–6 months were used.

Animals were randomly divided into two groups: control (CT) and tail-suspended hindlimb-unloaded (HU) groups. Hindlimb suspension was performed as previously described (Desaphy et al. 1998) and was approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Bari. Briefly, the animal was placed in a special cage that allowed only the forelimbs to touch the bottom of the cage while the hindlimbs were free and suspended; the animal’s body was inclined at about 45° from the horizontal. Control and suspended animals had food and water ad libitum. At the end of the period of suspension (2 weeks), four CT and four HU mice were sacrificed under deep anesthesia induced by intraperitoneal injection of urethane. All animals were sacrificed within 1 h in the morning to avoid differences in circadian and homeostatic sleep–wake factors. The brains were immediately removed and placed in liquid nitrogen.

RNA extraction and probing

A total of 60 μg total RNA, extracted in trizol from each brain was reverse transcribed into cDNA in the presence of fluorescent Cy3-dUTP (green) or Cy5-dUTP (red) according to the AECOM protocol (fully described at http://microarray1k.aecom.yu.edu/Microarray Hybridization Protocols). After hybridization, the slides were washed at room temperature, using solutions containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 1% SSC (3 M NaCl + 0.3 M sodium citrate) to remove the non-hybridized cDNAs.

Microarray

Green and red fluorescent labeled extracts were cohybridized with four mouse 27 k cDNA microarray slides produced by the Microarray Facility of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (http://microarray1k.aecom.yu.edu). We used the “multiple yellow” design (Iacobas et al. 2006) in which each slide was hybridized with Cy5/Cy3-cDNA from the brains of two mice subjected to the same condition. Images were acquired and initially analyzed with GenePix Pro 6.0 software (http://www.moleculardevices.com/pages/software/gn_genepix_pro.html) then normalized as described elsewhere (Iacobas et al. 2005). A gene was considered as quantifiable in a sample if the corresponding spot had a foreground fluorescence more than twice the background and it was not saturated. In order to minimize errors caused by the different labeling efficiencies of Cy3 and Cy5, we compared the 2 Cy3-labeled HUmRNA to the 2 Cy3-labeled CT-mRNA and the 2 Cy5-labeled HU-mRNA to the 2 Cy5-labeled CT-mRNA and then averaged the four ratios for each probed transcript. In the case of a gene probed with multiple spots on a single array, the expression ratio was the weighted average ratios, as previously described (Iacobas et al. 2005). The data set (series no. GSE) was deposited in the gene expression omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) as platform GPL1698, and series (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE12312) GSE12312.

Functional categories

The proteins encoded by the quantified genes were categorized as: CSD cell cycle, shape, differentiation, death (A apoptosis, C cell cycle (cyclin), D development, differentiation, organogenesis, G growth factors, hormones, cytokines, S shape, N oNcogenes, O others), CYT cytoskeleton, ENE energy metabolism (MIT mitochondrial proteins involved in cyclic acid cycle, respiratory chain, L lipid metabolism, D degradation such as in peroxisomes, proteasome ubiquitination, G glycolysis, glycogenesis, O others), JAE cell junction, adhesion, extracellular matrix (A antigens, integrins, G globulins and blood, M extracellular matrix, laminin, J junction and associated proteins, P proteases (such as metalloproteinases), O others), RNA RNA processing (M mRNA, R rRNA, T tRNA, MIT mitochondrial RNA), SIG cell signaling (G-proteins coupled receptors, PKA, PKC, cAMP, calcium, MAPK, SH2, SH3, Ca-binding proteins), TIC transport of small molecules and ions into the cells (transporters, ion channels, ionotropic receptors), TRA transcription (D DNA transcription factors, P DNA processing (such as polymerases), O others), TWC transport of ions/molecules within the cells (vesicles, kinesin, endosomes, proteosomes, protein folding, lysosomes, nuclear transport), UNK function not yet assigned (with some minor modifications as in Iacobas et al. 2005). In addition, gene expression of normal and HU mice were compared using GenMapp and MappFinder software (http://www.genemapp.org), where expression is linked to functional and structural pathways and where z-scores compute whether altered expression is significantly different from chance.

Expression regulation

Detection of significantly regulated genes relied on both fold-change in expression ratio (negative for down-regulation, |X| > 1.5 to exceed the average technical noise of the method and the expression variability among animals) and on statistical significance (P < 0.01) using the two-tailed t test for equality of two ratios and a Bonferroni-type adjustment (Iacobas et al. 2005). Although we have not confirmed these microarray data by an alternative method, we have validated our microarray method by qRT-PCR in other studies (e.g. Iacobas et al. 2005, 2008a) and therefore we are confident that our detection of regulated genes is accurate.

Variability and control of transcript abundance

The relative estimated variability (REV) was used to determine the gene expression stability (GES) of individual genes in each condition and to identify the very stably expressed (GES >95) and the very unstably expressed (GES <5) genes as previously described (Iacobas et al. 2005). Genes with GES = 100 had the least dispersion while genes with GES = 0 had the largest dispersion of expression levels within the set of four mice subjected to the same condition. Further, REV analysis was used to evaluate the change of control stringency and GES analysis to identify the genes with major changes in expression stability induced by the stress.

Results

Altered gene expression in brains of HU mice

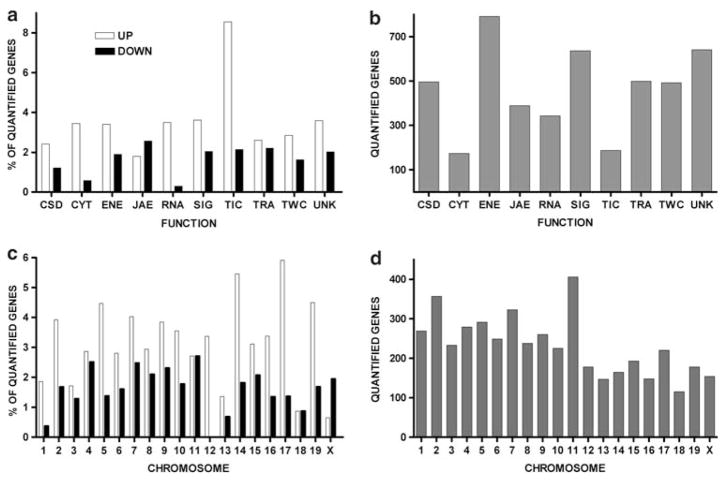

We quantified expression levels of 4,749 distinct genes with well-annotated protein products in brains of CT and HU animals. Using a moderately stringent cut-off (|X| > 1.5 and P < 0.05) 592 well-annotated unigenes (12.7%) significantly changed their expression levels. Of these, 258 genes were down-regulated (43.5%) and 334 (56.5%) were up-regulated. Using a higher stringency cut-off (|X| > 1.5 and P < 0.01) only 5% (235) of the quantified genes were considered significantly altered. Although at different levels, genes within all functional categories displayed significantly altered expression (see Fig. 1a, b) indicating that HU affected brain genes that encode proteins involved in a wide range of cellular functions. The significantly regulated genes were localized on all chromosomes (Fig. 1c, d). Together, these findings indicate that considerable transcriptomic alterations are induced by the change in blood pressure and fluxes due to the tail suspended position.

Fig. 1.

Percent of regulated (a, c) out of quantified (b, d) genes in the brain of HU mice. Note that all functional categories and all chromosomes were affected as a result of the hindlimb suspension, with TIC genes showing highest percentage of up-regulated genes and JAE the lowest

Interestingly, with the exception of the JAE class all other classes manifested a higher percentage of up-regulated genes than down-regulated genes. The TIC class had the highest percentage of up-regulated genes, while the most down-regulated genes were those of the JAE class. Noteworthy, the TIC showed the highest number of altered genes (16%, P < 0.05), indicating that HU greatly affected the transport of ions and molecules into the cells. These genes included sodium channel, nonvoltage-gated 1 beta (Scnn1b), glutamate receptor (Grin1), voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (Vdac1), calcium channel, voltage-dependent, beta 3 subunit (Cacnb3), potassium voltage-gated channel, Shaw-related subfamily, member 4 (Kcnc4), potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily Q, member 2 (Kcnq2) and others.

Table 1 presents the most 25 up- and down-regulated genes, along with the expression ratio and Bonferroni-corrected P values. A complete list of the altered genes is available in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

The most 25 up- and down-regulated genes in HU mice

| Name | Symbol | CHR | FUNC | CAT | RATIO | P VAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 antigen | Cd44 | 2 | JAE | A | 2.84 | 0.005 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase 2, B chain | Ldh2 | 6 | ENE | G | 2.60 | 0.001 |

| ATPase, H+ transporting, V0 subunit C | Atp6v0c | 17 | TIC | 2.59 | 0.001 | |

| ORM1-like 3 (S. cerevisiae) | Ormdl3 | 11 | UNK | 2.45 | 0.003 | |

| Immature colon carcinoma transcript 1 | Ict1 | 11 | UNK | 2.45 | 0.001 | |

| Ewing sarcoma homolog | Ewsh | 11 | SIG | 2.42 | 0.006 | |

| Brain protein 44-like | Brp44 l | 17 | UNK | 2.37 | 0.000 | |

| RalA binding protein 1 | Ralbp1 | 17 | SIG | 2.37 | 0.000 | |

| N-myc downstream regulated 2 | Ndr2 | 14 | CSD | D | 2.36 | 0.009 |

| Prion protein interacting protein 1 | Prnpip1 | 4 | TWC | 2.30 | 0.005 | |

| DNA primase, p58 subunit | Prim2 | 1 | TRA | P | 2.28 | 0.009 |

| ATPase, class VI, type 11A | Atp11a | 8 | TIC | 2.28 | 0.001 | |

| Nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic, calcineurin-dependent 4 | Nfatc4 | 14 | TRA | D | 2.27 | 0.002 |

| Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II gamma | Camk2 g | 14 | SIG | 2.24 | 0.000 | |

| Rho GTPase activating protein 5 | Arhgap5 | 12 | UNK | 2.23 | 0.006 | |

| Farnesyl diphosphate farnesyl transferase 1 | Fdft1 | 14 | ENE | L | 2.23 | 0.010 |

| Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 1 | Cnp1 | 11 | SIG | 2.21 | 0.001 | |

| Developmentally and sexually retarded with transient immune abnormalities | Desrt | 10 | TRA | D | 2.21 | 0.007 |

| Dual specificity phosphatase 1 | Dusp1 | 17 | SIG | 2.21 | 0.001 | |

| RAN, member RAS oncogene family | Ran | 5 | SIG | 2.19 | 0.003 | |

| Syntaxin binding protein 1 | Stxbp1 | 2 | TWC | 2.17 | 0.003 | |

| Differentially expressed in FDCP 8 | Def8 | 8 | SIG | 2.16 | 0.000 | |

| DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 39 | Ddx39 | 8 | TRA | P | 2.15 | 0.002 |

| PHD finger protein 1 | Phf1 | 17 | UNK | 2.13 | 0.003 | |

| PRP39 pre-mRNA processing factor 39 homolog (yeast) | Prpf39 | 12 | RNA | M | 2.13 | 0.006 |

| Rab6 GTPase activating protein (GAP and centrosome-associated) | Gapcena 2 | 2 | TWC | −4.20 | 0.002 | |

| Kinesin family member 1C | Kif1c | 11 | TWC | −3.69 | 0.004 | |

| Uridine monophosphate kinase | Umpk | 2 | SIG | −3.58 | 0.008 | |

| Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 1b | Tnfrsf1b | 4 | CSD | G | −3.57 | 0.004 |

| Apical protein, Xenopus laevis-like | Apxl | X | TIC | −3.34 | 0.010 | |

| Claudin 7 | Cldn7 | 11 | JAE | J | −3.31 | 0.001 |

| Nucleolar protein ANKT | Ankt-pending | 2 | UNK | −3.23 | 0.001 | |

| GA repeat binding protein, beta 2 | Gabpb2 | 3 | TRA | D | −3.19 | 0.009 |

| Regulatory factor X-associated ankyrin-containing protein | Rfxank | 8 | TWC | −3.11 | 0.004 | |

| Endothelial-specific receptor tyrosine kinase | Tek | 4 | SIG | −3.10 | 0.009 | |

| 5phosphorylase kinase, gamma 2 (testis) | Phkg2 | 7 | SIG | −3.03 | 0.002 | |

| Solute carrier family 11 (proton-coupled divalent metal ion transporters), member 2 | Slc11a2 | 15 | TIC | −2.99 | 0.008 | |

| Fibroblast growth factor inducible 15 | Fin15 | 6 | CSD | G | −2.93 | 0.010 |

| EGF, latrophilin seven transmembrane domain containing 1 | Eltd1 | 3 | JAE | J | −2.77 | 0.000 |

| CEA-related cell adhesion molecule 11 | Ceacam11 | 7 | JAE | J | −2.77 | 0.003 |

| CEA-related cell adhesion molecule 11 | Ceacam11 | 7 | JAE | J | −2.77 | 0.003 |

| Chromatin accessibility complex 1 | Chrac1 | 15 | TRA | P | −2.74 | 0.002 |

| Potassium channel tetramerisation domain containing 10 | Kctd10 | 5 | TIC | −2.64 | 0.004 | |

| Mak3p homolog (S. cerevisiae) | Mak3p | 16 | ENE | O | −2.64 | 0.001 |

| Angiogenin | Ang | 14 | ENE | O | 2.61 | 0.003 |

| Zinc finger, DHHC domain containing 1 | Zdhhc1 | 8 | UNK | −2.59 | 0.009 | |

| Similar to KRAB zinc finger protein (Mzf22) | LOC235907 | U | UNK | −2.58 | 0.009 | |

| Tissue factor pathway inhibitor | Tfpi | 2 | ENE | D | −2.53 | 0.006 |

| Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase, mitochondrial | Gpam | 19 | ENE | MIT | −2.48 | 0.010 |

| Serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor, clade C (antithrombin), member 1 | Serpinc1 | 1 | JAE | P | −2.46 | 0.009 |

CHR chromosomal location, FUNC functional category, CAT subcategory, RATIO fold-change (negative for downregulation), P VAL Bonferroni-type corrected P value of the redundancy group

Expression variability and strength of the transcription control

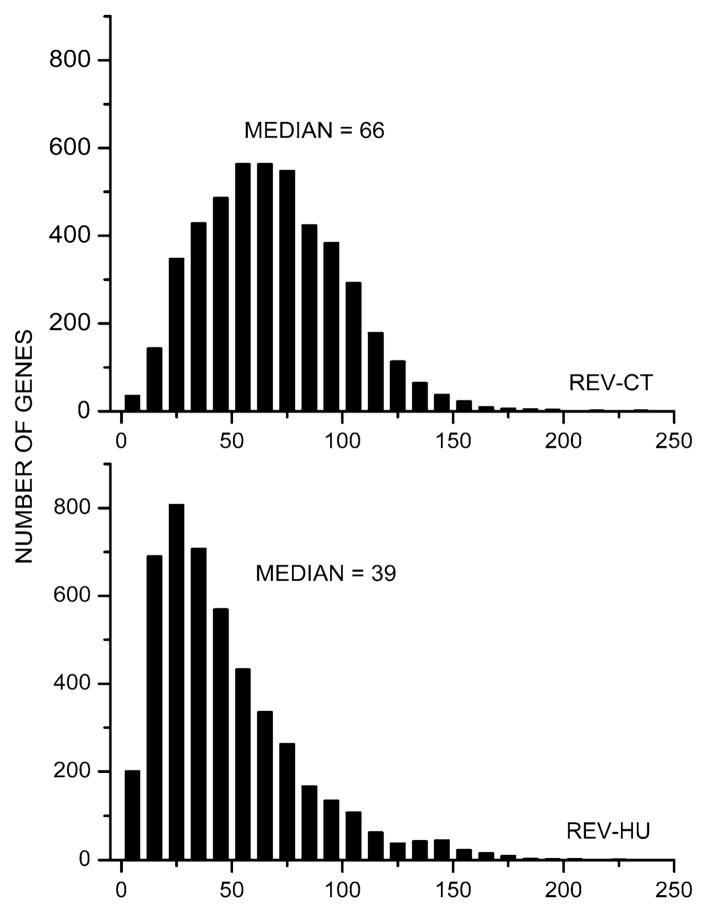

Figure 2 presents the histograms of REV values for both conditions. It should be noted that individual genes exhibited a wide range of expression variability in both conditions (from less than 10% on all four arrays to over two fold) indicating that the transcription control stringency is not uniform among genes. Note that the hindlimb suspension reduced the median REV value from 66 to 39%, indicating a significant increase of transcription control, presumably to limit the expression alterations.

Fig. 2.

Histograms of the relative expression variability in brain of control (CT) and tail- suspended (HU) mice. Note the substantial reduction of the median relative expression variability in HU mice compared to that of CT mice indicating a significant increase of the overall control of transcripts’ abundance

Although the reduction of expression variability was not uniform among the genes, the hierarchy of the transcription control (determined by GES scores) was not significantly altered as exemplified in Table 2. Altogether-, 8.5% of the quantified genes preserved their high stability (GES >95%), 8.0% their high instability (GES <5), while 4.7% switched from very stably expressed to very unstable and 1.6% from very unstable to very stable, the remaining genes having less significant maintenance or change in the stability class.

Table 2.

Genes that preserved/reverted transcript abundance stability/instability in the brain of HU mice

| Gene | Symbol | CHR | FUNC-C | GES-CT | GES-HU | OBS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase | Acac | 11 | ENE-O | 99.96 | 99.21 | SS |

| Adducin 1 (alpha) | Add1 | 5 | CYT | 98.95 | 99.74 | SS |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase 5 (class III), chi polypeptide | Adh5 | 3 | ENE-O | 99.43 | 96.47 | SS |

| CDK2 (cyclin-dependent kinase 2)-associated protein 1 | Cdkap1 | 5 | CSD-C | 97.13 | 98.22 | SS |

| Fos-like antigen 2 | Fosl2 | 5 | TRA-D | 95.58 | 95.50 | SS |

| Inter alpha-trypsin inhibitor, heavy chain 4 | Itih4 | 14 | ENE-D | 96.92 | 98.26 | SS |

| Kinesin family member 23 | Kif23 | 9 | TWC | 97.45 | 99.53 | SS |

| LPS-induced TN factor | Litaf | 16 | SIG | 96.26 | 96.83 | SS |

| Malonyl-CoA decarboxylase | Mlycd | 8 | ENE-O | 97.49 | 96.31 | SS |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 interacting protein 1 | Map2k1ip1 | 3 | SIG | 97.35 | 95.73 | SS |

| PR domain containing 4 | Prdm4 | 10 | UNK | 96.42 | 95.01 | SS |

| Protein tyrosine phosphatase 4a3 | Ptp4a3 | 15 | SIG | 99.36 | 95.40 | SS |

| Protocadherin gamma subfamily B, 1 | Pcdhgb1 | 18 | JAE-J | 97.43 | 98.28 | SS |

| Serologically defined colon cancer antigen 33 | Sdccag33 | 18 | JAE-A | 97.90 | 99.30 | SS |

| Spermatid perinuclear RNA binding protein | Spnr | 2 | RNA-M | 99.71 | 95.94 | SS |

| Thioesterase superfamily member 2 | Them2 | 13 | ENE-O | 98.20 | 96.17 | SS |

| Tripartite motif protein 8 | Trim8 | 19 | UNK | 99.20 | 98.73 | SS |

| BCL2-like 12 (proline rich) | Bcl2l12 | 7 | CSD-A | 97.69 | 3.80 | SU |

| Biliverdin reductase A | Blvra | 2 | ENE-O | 97.41 | 1.08 | SU |

| Chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1 | Cx3cl1 | 8 | CSD-G | 97.42 | 2.87 | SU |

| Glyoxylate reductase/hydroxypyruvate reductase | Grhpr | 4 | ENE-O | 96.46 | 0.03 | SU |

| Inner membrane protein, mitochondrial | Immt | 6 | ENE-MIT | 97.07 | 1.89 | SU |

| Nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group F, member 1 | Nr2f1 | 13 | CSD-G | 95.06 | 1.83 | SU |

| Poly(rC) binding protein 4 | Pcbp4 | 9 | RNA-M | 98.50 | 1.68 | SU |

| Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 11 | Ppp1r11 | 17 | SIG | 99.29 | 4.45 | SU |

| Ring finger protein 44 | Rnf44 | 13 | UNK | 96.52 | 0.08 | SU |

| SH3 domain binding glutamic acid-rich protein-like 3 | Sh3bgrl3 | 4 | UNK | 99.56 | 4.36 | SU |

| Abhydrolase domain containing 2 | Abhd2 | 7 | ENE-O | 1.49 | 96.19 | US |

| Asrij | Asrij | 5 | UNK | 3.02 | 96.93 | US |

| Stromal cell derived factor 4 | Sdf4 | 4 | JAE-M | 3.35 | 95.62 | US |

| Zinc finger protein (C2H2 type) 276 | Zfp276 | 8 | UNK | 0.35 | 98.07 | US |

| Angiomotin-like 1 | Amotl1 | 9 | UNK | 0.88 | 0.17 | UU |

| CLIP associating protein 1 | Clasp1 | 1 | CYT | 3.29 | 3.43 | UU |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 | Cdk2 | 10 | SIG | 2.57 | 1.69 | UU |

| Dihydropyrimidinase-like 2 | Dpysl2 | 14 | ENE-O | 2.04 | 4.55 | UU |

| Fat specific gene 27 | Fsp27 | 6 | CSD-A | 4.47 | 3.42 | UU |

| Fidgetin-like 1 | Fignl1 | 11 | UNK | 2.73 | 0.68 | UU |

| Heat shock protein 105 | Hsp105 | 5 | TWC | 1.78 | 0.84 | UU |

| KDEL (Lys-Asp-Glu-Leu) endoplasmic reticulum protein retention receptor 3 | Kdelr3 | 15 | TWC | 3.82 | 2.61 | UU |

| Mannosidase 1, alpha | Man1a | 10 | ENE-D | 4.42 | 1.47 | UU |

| Neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulted gene 4 | Nedd4 | 9 | ENE-D | 0.13 | 3.72 | UU |

| Nuclear DNA binding protein | C1d | 11 | TRA-D | 4.69 | 1.87 | UU |

| Nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group C, member 2 | Nr2c2 | 6 | CSD-G | 1.56 | 0.34 | UU |

| Nuclear respiratory factor 1 | Nrf1 | 6 | TRA-D | 1.41 | 0.11 | UU |

| Nucleoredoxin | Nxn | 11 | ENE-O | 4.81 | 3.84 | UU |

| Proteasome (prosome, macropain) 26S subunit, ATPase 3 | Psmc3 | 2 | ENE-D | 1.27 | 1.35 | UU |

| Proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, alpha type 3 | Psma3 | 12 | ENE-D | 3.46 | 2.36 | UU |

| Protein (peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase) NIMA-interacting 1 | Pin1 | 9 | TWC | 1.57 | 0.24 | UU |

| Secretory carrier membrane protein 1 | Scamp1 | 13 | TWC | 1.08 | 0.53 | UU |

| Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 7 | Sfrs7 | 17 | RNA-M | 4.95 | 0.62 | UU |

| T-box 5 | Tbx5 | 5 | TRA-D | 3.57 | 3.84 | UU |

| Wingless-related MMTV integration site 2 | Wnt2 | 6 | SIG | 1.68 | 2.88 | UU |

OBS observation, SS, SU, US, UU whether the very stably (U) or unstably (U) expressed gene in control maintained (SS, UU) or switched (SU, US) the stability classification in tail suspended mice

While genes such as Amoti1, Nedd4 and Zfp276 or Sh3bgrl3, Ppp1r11 and Acac maintained their instability/stability of transcription under the stress, Spnr, Adh5, Ptp4a3, Trim8 were found most stably transcribed in normal brains.

Discussion

In this study we have shown that HU in mice determines altered expression of numerous genes in the brain. These genes code for proteins that are involved in a wide range of cell functions suggesting that HU may affect multiple aspects of brain function in order to compensate for changes in fluid shift in this model of microgravity. Some of these genes are specifically expressed in neurons, others are expressed in glial cells and some in both.

We have found that HU significantly decreased the overall gene expression variability. This result is consistent with our findings in previous microarray studies of kidney (Iacobas et al. 2006) and heart (Iacobas et al. 2008b) of mice subjected to chronic constant or intermittent hypoxia for 1, 2 or 4 weeks of their early life. We interpreted these findings of overall reduction of expression variability in tissues of mice exposed to major stresses as an indication that overall strength of the transcription control is increased, presumably reflecting cellular effort to limit the alterations. This conclusion is also supported by the significant variability reduction in hearts of Cx43 null mice (Iacobas et al. 2005) and in brains of Cx43, Cx32 or Cx36 null mice (e.g. Iacobas et al. 2007).

The analysis performed by GeneMAPP revealed several altered protein classes and functional pathways concerning blood coagulation (z score 3.4), immune response (z score 3.5), learning and memory, synaptic transmission, ion channels, cytoskeleton and cell junction.

Blood coagulation

In the coagulation pathway six genes were altered and all of them were down-regulated. These genes were Proc, Serpinc1, Serpind1, Tfpi, Anxa2 and F2rl3.

Protein C (Proc), a vitamin K-dependent serine protease zymogen, is a key component of the anticoagulant pathway and is important for maintaining normal hemostasis and for regulation of the immune response during inflammation. Activated protein C inhibits thrombin formation by inactivation of factors Va and VIIIa through limited proteolysis thus inhibiting the coagulation process. The importance of protein C in hemostasis has been confirmed with the identification of patients with both hereditary and acquired deficiency of the protein. Individuals with severe protein C deficiency suffer severe microvascular thrombotic disease (Esmon 2001). Recently a mouse expressing reduced levels of protein C was generated (Lay et al. 2005). These mice developed thrombosis and inflammation, the onset and severity of which varied significantly and were strongly dependent on plasma protein C levels.

The second natural anticoagulant system that is able to exert damping effects on the various steps of the cascade is the heparin-antithrombin mechanism. Both antithrombin III (serpinc1, AT) and heparin cofactor2 (serpind 1, HC2) are inhibitors of thrombin activity in a reaction that is noticeably accelerated by glycosaminoglycans. Thrombin is a multifunctional serine protease that plays a critical role in blood coagulation and hemostasis. HC2 and AT are mainly synthesized in the liver and in liver-derived cell lines (Ragg and Preibisch 1988; Zhang et al. 1994). However, both the mRNAs and proteins are found in various human organs (Kamp et al. 2001), including brain. As widely reported for Proc, AT and HC2 deficiency also results in venous thrombosis (Cooper 1991).

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) is also involved in blood coagulation. TFPI is a serine protease inhibitor of the Factor VIIa/Tissue Factor-initiated clotting cascade in the extrinsic blood coagulation pathway (Davie et al. 1991). Although an association between TFPI deficiency and thrombosis has still not been clearly demonstrated, a reduced anticoagulant response to TFPI has been found in patients with venous thrombosis (Tardy-Poncet et al. 2003). Furthermore, deficiency of TFPI promotes atherosclerosis and thrombosis in mice (Westrick et al. 2001) while a large number of TFPI null mice die between embryonic days 9.5 and 11.5 with signs of yolk sac hemorrhage (Broze 1998).

Annexin II is a calcium-regulated and phospholipid-binding surface protein that serves as a profibrinolytic co-receptor for tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen on endothelial cells, facilitating plasmin generation on the surface of vascular endothelium. Studies of humans with acute promyelocytic leukemia suggest that overexpression of annexin II on leukemic blast cells leads to dysregulated plasmin generation and a hyperfibrinolytic hemorrhagic state (Menell et al. 1999). Studies in null mice showed that dysregulation of fibrinolytic assembly on endothelial cells leads to atherothrombotic disease indicating a regulatory role for annexin II in maintaining hemostatic balance. Indeed, Anxa2 null mice exhibit deposition of fibrin in the microvasculature and incomplete clearance of injury-induced arterial thrombi (Ling et al. 2004).

The last gene that was significantly down-regulated was the coagulation factor II receptor-like 3 (F2rl3), also called PAR4. It belongs to a protease-activated receptor (PARs) sub-group of the G-protein-coupled receptor super family. Activated PARs are coupled to signaling cascades that affect many cell functions including shape, secretion, and cell motility (Cottrell et al. 2002). In particular, thrombin activates PAR4 at the surface of platelets, resulting in aggregation and formation of a stable hemostatic plug. Activation of this process has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of thrombosis (Ossovskaya and Bunnet 2004). Importantly, PAR4-deficient mice had markedly prolonged bleeding times and were protected in a model of arteriolar thrombosis (Hamilton et al. 2004).

The microarray analysis demonstrates that the blood coagulation pathway is significantly altered. In particular, five out of six down-regulated genes are directly involved in blood coagulation, while PAR4 is involved in fibrinolysis. This suggests that HU may cause an alteration in hemostasis which results in a shift toward a more hypercoagulative state with an increased risk for venous thrombosis. However, down-regulation of PAR4 could counteract this effect and compensate for the intense gene alteration (in the direction of less viscous blood). It has been reported that in humans unilateral lower limb suspension can cause deep venous thrombosis (Bleeker et al. 2004). Thus our data confirm that HU determines a hypercoagulative state and suggest that a similar hemostasis alteration can occur during other microgravity conditions such as space flight. To our knowledge, no cases of thrombosis have been reported after spaceflights. However, the limited number of people exposed to microgravity and the stricter screening of subject selection for spaceflight missions does not allow a consistent assessment of the risk of thrombosis. Nevertheless, in a study conducted to evaluate the effect of space flights on the human immunologic and hematologic systems, it has been found that in a Skylab mission there were “changes in the proteins involved in the coagulation process which suggested a hypercoagulative condition” (Kimzey et al. 1975).

Although the new coagulative condition in HU animals could have a vascular origin it is of interest to note that some of these proteins are also localized in the brain. Thus, their alteration, in addition to the effect on the brain blood circulation, would also have other brain specific effects. Indeed, both Par4 (Suo et al. 2003) and TFPI (Hollister et al. 1996) have been immunohistochemically localized to microglia. It has been reported (Suo et al. 2003) that PAR4 intracellular signaling is responsible for activating microglia and thrombin-induced TNF-α release by microglia which may also contribute to inflammation in the brain. HCT2 mRNA transcript was also detected in brain tissue (Kamp et al. 2001) although to low expression levels. Finally annexin II has been detected in brain lipid raft fractions from neurons and is involved in learning mechanisms (Zhao et al. 2004; Ledesma et al. 2003).

Learning and memory

Another pathway that exhibited significantly altered gene expression in the brains of HU animals is that involved in learning and memory.

Two genes were significantly altered in this pattern. Grin1 was up-regulated and Itga3 was down-regulated.

Grin1 encodes for the glutamate receptor subunit 1(NMDAR1) which acts as glutamate-gated cation channels. Molecular studies have indicated that NMDA receptors exist as multiple subunits containing both NMDAR1 and NMDAR2A-2D subtypes (Stephenson et al. 2008). However, NMDAR1 is the fundamental subunit that possesses all properties characteristic of the NMDA receptor channel complex (Nakanishi et al. 1998).

Glutamate receptors are the predominant excitatory neurotransmitter receptors in the mammalian brain and are important in neural plasticity, neural development and neurodegeneration. In particular several results indicate that hippocampal NMDA receptors are involved in human memory (Grunwald et al. 1999). The NMDAR is localized at the post synaptic membrane but the number and composition of synaptic NMDARs can be modulated by several factors. Recent data indicate that the most important mechanism by which neurons regulate excitatory transmission is by the number of receptors in the membrane, which can be changed rapidly by internalization (Roche et al. 2001). Upregulation of NMDAR may increase capacity of learning and memory, but their excessive stimulation results in excitotoxic death. However, there is also an emerging role for NMDAR in supporting neuronal survival (Hetman and Kharebava 2006).

Itga3 encodes for the alpha3 subunit of the transmembrane heterodimeric (α, β) complex. Integrins are a family of cell surface adhesion molecules that mediate both cell–cell and cell-matrix interactions throughout the body (Schwartz et al. 1995). They also organize the elements of the submembrane actin cytoskeleton (Geiger et al. 2001) and act as receptors for a number of intracellular signaling cascades (Schwartz et al. 1995). Recent studies have revealed novel roles for integrins in brain cells development, neuropathology, and learning and memory (Lin et al. 2003; Grotewiel et al. 1998, Chan et al. 2003). Furthermore, results indicate that integrins can modulate fast excitatory transmission at hippocampal synapses by modifying the activities of both AMPA-type MDAR glutamate receptors (Kramar et al. 2003).

For two other genes that were also annotated in the pathway (vdac1,3) there are only few a studies (Traina et al. 2006 Weeber et al. 2002). VDACs are voltage-dependent anion channels abundantly expressed in the outer membrane of all eukaryotic mitochondria that provide passage for adenine nucleotides, Ca2+ and other metabolites into and from mitochondria by passive diffusion (Hodge and Colombini 1997). Moreover, a plasmalemmal form of VDAC is observed in astrocytes (Buettner et al. 2000).

Opening of plasma membrane VDAC channels was shown to be involved in apoptotic cell death, which is an essential process in the development of the central nervous system and in the pathogenesis of its degenerative diseases (Elinder et al. 2005). Importantly, VDAC-deficient mice exhibit spatial learning deficits as well as deficits in long and short term synaptic plasticity (Weeber et al. 2002). Thus the increasing in vidac1,3 by HU treatment seems to have a relevant role in events related to synaptic plasticity and learning processes.

Ion channels

Scnn1b is the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel beta subunit. Gain-of-function mutations as well as polymorphisms have been found in scnn1b that are responsible for Liddle’s syndrome and propensity to hypertension (Tong et al. 2006). Recently, expression of Scnn1b was found in both the epithelial and neural components of rat brain, which may contribute to regulation of cerebrospinal fluid and interstitial Na+ concentration as well as neuronal excitation (Amin et al. 2005).

The beta 3 subunit of the voltage-gated N-type calcium channels regulates the activation (opening) and inactivation (closing) kinetics through phosphorylation/dephosphorylation (Hering et al. 2000). In human brains, a strong expression of Cacnb3 mRNA was found in the medial habenular nucleus, a high level of expression was observed in the olfactory bulb and cerebellum, and a relatively high level of Cacnb3 mRNA was localized in the cerebral cortex, caudate-putamen and hippocampal formation (Park et al. 1997). Microarray analysis of hippocampus gene expression in global cerebral ischemia revealed an increased expression of Cacnb3 as a component of functional modules within the ischemic neuronal transcriptome (Jin et al. 2001). In rodents, Beta3 subunit may be also important for the pheromone signal transduction system (Murakami et al. 2006). Finally, a recent study shows that β3 channel null-mutant mice have impaired learning ability (Murakami et al. 2007).

Kcnc4 encodes the potassium channel Kv3.4 expressed in the brain and fast-twitch muscle fibers (Ohya et al. 1997). In the brain, the pre and postsynaptic localization of Kv3.4 suggests a role both in the control of transmitter release and in regulating neuronal excitability (Brooke et al. 2004). As in the case of vdac1, kcnc4 upregulation has been associated with neurodegenative structures in Alzheimer’s disease (Angulo et al. 2004).

Kcnq2 encodes a subunit of the M channel, a widely expressed potassium channel that mediates effects of modulatory neurotransmitters and controls repetitive neuronal discharges. Indeed mutations in this gene were associated with benign familial neonatal convulsions, a rare idiopathic, generalized epilepsy syndrome. KCNQ channels are the target of several drugs in development for treatment of Alzheimer disease, epilepsy, and stroke (Cooper 2001). In particular, the anticonvulsivant retigabine, currently in phase III clinical trial, is thought to act primarily by opening KCNQ channels (Hansen et al. 2006).

In conclusion HU suspension determines a modification of numerous genes in the brain that are involved in many biological functions. Some of them are directly due to the fluid changes occurring in this animal model of microgravity. However, it can not be excluded that other correlated events such as the absence of exercise and the animal’s stress may also have an impact on neural function.

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00221-008-1523-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Acknowledgments

The financial support from the Italian Space Agency (I/R/372/02, OSMA) is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- CT

Control

- GES

Gene expression stability

- HU

Hindlimb-unloaded

- REV

Relative estimated variability

- CSD

Cell cycle, shape, differentiation, death [A apoptosis, C cell cycle (cyclin), D development, differentiation, organogenesis, G growth factors, hormones, cytokines, S shape, N oNcogenes, O others]

- CYT

Cytoskeleton

- ENE

Energy metabolism

- MIT

Mitochondrial proteins involved in cyclic acid cycle, respiratory chain (L lipid metabolism, D degradation such as in peroxisomes, proteasome ubiquitination, G glycolysis, glycogenesis, O others)

- JAE

Cell junction, adhesion, extracellular matrix [A antigens, integrins, G globulins and blood, M extracellular matrix, laminin, J junction and associated proteins, P proteases (such as metalloproteinases), O others]

- RNA

RNA processing (M mRNA, R rRNA, T tRNA, MIT mitochondrial RNA)

- SIG

Cell signaling (G-proteins coupled receptors PKA PKC cAMP calcium MAPK SH2 SH3 Ca-binding proteins)

- TIC

Transport of small molecules and ions into the cells (transporters ion channels ionotropic receptors)

- TRA

Transcription [D DNA transcription factors, P DNA processing (such as polymerases), O others]

- TWC

Transport of ions/molecules within the cells (vesicles, kinesin, endosomes, proteosomes, protein folding, lysosomes, nuclear transport)

- UNK

Function not yet assigned

References

- Amin MS, Wang HW, Reza E, Whitman SC, Tuana BS, Leenen FH. Distribution of epithelial sodium channels and mineral-ocorticoid receptors in cardiovascular regulatory centers in rat brain. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1787–R1797. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00063.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo E, Noé V, Casadó V, Mallol J, Gomez-Isla T, Lluis C, Ferrer I, Ciudad CJ, Franco R. Up-regulation of the Kv34 potassium channel subunit in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2004;91:547–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belichenko PV. Quantitative analysis of dendritic spines of pyramidal neurons in the layers of the sensorimotor cortex of rats exposed to the Cosmos-1667 biosputnik. Biull Eksp Biol Med. 1998;105:736–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleeker MW, Hopman MT, Rongen GA, Smits P. Unilateral lower limb suspension can cause deep venous thrombosis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R1176–R1177. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00718.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke RE, Atkinson L, Batten TF, Deuchars SA, Deuchars J. Association of potassium channel Kv34 subunits with pre- and post-synaptic structures in brainstem and spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2004;126:1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broze GJ. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor gene disruption. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1998;9:S89–S92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner R, Papoutsoglou G, Scemes E, Spray DC, Dermietzel R. Evidence for secretory pathway localization of a voltage-dependent anion channel isoform. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3201–3206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060242297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro S, D’Agata V, Manickam P, Dufour F, Alkon DL. Memory-specific temporal profiles of gene expression in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16279–16284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242597199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Weeber EJ, Kurup S, Sweatt JD, Davis RL. Integrin requirement for hippocampal synaptic plasticity and spatial memory. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7107–7116. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-18-07107.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convertino VA, Doerr DF, Mathes KL, Stein SL, Buchanan P. Changes in volume, muscle compartment, and compliance of the lower extremities in man following 30 days of exposure to simulated microgravity. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1989;60:653–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DN. The molecular genetics of familial venous thrombosis. Blood Rev. 1991;5:55–70. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(91)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper EC. Potassium channels: how genetic studies of epileptic syndromes open paths to new therapeutic targets and drugs. Epilepsia. 2001;5:49–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.0420s5049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell GS, Coelho AM, Bunnett NW. Protease-activated receptors: the role of cell-surface proteolysis in signaling. Essays Biochem. 2002;38:169–183. doi: 10.1042/bse0380169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie EW, Fujikawa K, Kisiel W. The coagulation cascade: initiation, maintenance, and regulation. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10363–10370. doi: 10.1021/bi00107a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, Arellano JI, Merchán-Pérez A, González-Albo MC, Walton K, Llinás R. Spaceflight induces changes in the synaptic circuitry of the postnatal developing neocortex. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:883–891. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.8.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Signore A, Mandillo S, Rizzo A, Di Mauro E, Mele A, Negri R, Oliverio A, Paggi P. Hippocampal gene expression is modulated by hypergravity. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:667–677. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2004.03171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desaphy JF, Pierno S, Liantonio A, De Luca A, Leoty C, Conte Camerino D. Comparison of excitability parameters and sodium channel behavior of fast- and slow-twitch rat skeletal muscles for the study of the effects of hindlimb suspension, a model of hypogravity. J Gravit Physiol. 1998;5:77–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santo NG, Christensen NJ, Drummer C, Kramer HJ, Regnard J, Heer M, Cirillo M, Norsk P. Fluid balance and kidney function in space: introduction. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:664–667. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.27751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durzan DJ, Ventimiglia F, Havel L. Taxane recovery from cells of Taxus in micro- and hypergravity. Acta Astronaut. 1998;42:455–463. doi: 10.1016/s0094-5765(98)00138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinder F, Akanda N, Tofighi R, Shimizu S, Tsujimoto Y, Orrenius S, Ceccatelli S. Opening of plasma membrane voltage-dependent anion channels (VDAC) precedes caspase activation in neuronal apoptosis induced by toxic stimuli. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmon CT. Protein C anticoagulant pathway and its role in controlling microvascular thrombosis and inflammation. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S48–S51. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman RA. Cerebrospinal fluid in disease of the nervous system. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Frigeri A, Nicchia GP, Desaphy JF, Pierno S, De Luca A, Camerino DC, Svelto M. Muscle loading modulates aquaporin-4 expression in skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2001;15:1282–1284. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0525fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B, Bershadsky A, Pankov R, Yamada KM. Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix-cytoskeleton crosstalk. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:793–805. doi: 10.1038/35099066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotewiel MS, Beck CD, Wu CF, Greenspan RJ. Integrinmediated short-term memory in Drosophila. Nature. 1998;18:7847–7855. doi: 10.1038/35079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald T, Beck H, Lehnertz K, Blümcke I, Pezer N, Kurthen M, Fernández G, Van Roost D, Heinze HJ, Kutas M, Elger CE. Evidence relating human verbal memory to hippocampal N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12085–12089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen HH, Ebbesen C, Mathiesen C, Weikop P, Rønn LC, Waroux O, Scuvée-Moreau J, Seutin V, Mikkelsen JD. The KCNQ channel opener retigabine inhibits the activity of mesencephalic dopaminergic systems of the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:1006–1019. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.106757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargens AR, Steakai J, Johansson C, Tipton CM. Tissue fluid shift, forelimb loading, and tail tension in tail suspended rats. Physiologist. 1984;27:S37–S38. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JR, Cornelissen I, Coughlin SR. Impaired hemostasis and protection against thrombosis in protease-activated receptor 4-deficient mice is due to lack of thrombin signaling in platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:1429–1435. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering S, Berjukow S, Sokolov S, Marksteiner R, Weiss RG, Kraus R, Timin EN. Molecular determinants of inactivation in voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. J Physiol. 2000;528:237–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetman M, Kharebava G. Survival signaling pathways activated by NMDA receptors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:787–799. doi: 10.2174/156802606777057553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge T, Colombini M. Regulation of metabolite flux through voltage-gating of VDAC channels. J Membr Biol. 1997;157:271–279. doi: 10.1007/s002329900235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollister RD, Kisiel W, Hyman BT. Immunohistochemical localization of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-1 (TFPI-1), a Kunitz proteinase inhibitor, in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1996;728:13–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes-Fulford M, Lewis ML. Effects of microgravity on osteoblast growth activation. Exp Cell Res. 1996;224:103–109. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobas DA, Iacobas S, Li W, Zoidl G, Dermietzel R, Spray DC. Genes controlling multiple functional pathways are transcriptionally regulated in connexin43 null mouse heart. Physiol Gen. 2005;2:211–223. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00229.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobas DA, Fan C, Iacobas S, Spray DC, Haddad GG. Transcriptomic changes in developing kidney exposed to chronic hypoxia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobas DA, Iacobas S, Spray DC. Connexin-dependent transcellular transcriptomic networks in mouse brain. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2007;94:168–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobas DA, Iacobas S, Werner P, Scemes E, Spray DC. Alteration of transcriptomic networks in adoptive transfer experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Front Integr Neurosci. 2008a;1:10. doi: 10.3389/neuro.07/010.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobas DA, Fan C, Iacobas S, Haddad GG. Integrated transcriptomic response to cardiac chronic hypoxia: translation regulators and response to stress in cell survival. Funct Integr Genomics. 2008b;8(3):265–275. doi: 10.1007/s10142-008-0082-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Mao XO, Eshoo MW, Nagayama T, Minami M, Simon RP, Greenberg DA. Microarray analysis of hippocampal gene expression in global cerebral ischemia. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:93–103. doi: 10.1002/ana.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamp P, Strathmann A, Ragg H. Heparin cofactor II, antithrombin-beta and their complexes with thrombin in human tissues. Thromb Res. 2001;101:483–491. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(00)00422-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimzey SL, Ritzmann SE, Mengelm CE, Fischer CL. Skylab experiment results: hematology studies. Acta Astronaut. 1975;2:141–154. doi: 10.1016/0094-5765(75)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramar EA, Bernard JA, Gall CM, Lynch G. Integrins modulate fast excitatory transmission at hippocampal synapses. J Biol Chem. 2003;270:10722–10730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay AJ, Liang Z, Rosen ED, Castellino FJ. Mice with a severe deficiency in protein C display prothrombotic and proinflammatory phenotypes and compromised maternal reproductive capabilities. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1552–1561. doi: 10.1172/JCI24030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma MD, Da Silva JS, Schevchenko A, Wilm M, Dotti CG. Proteomic characterisation of neuronal sphingolipid-cholesterol microdomains: role in plasminogen activation. Brain Res. 2003;987:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03296-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis ML, Hughes-Fulford M. Regulation of heat shock protein message in Jurkat cells cultured under serum-starved and gravity-altered conditions. J Cell Biochem. 2000;77:127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Arai AC, Lynch G, Gall CM. Integrins regulate NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic currents. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2874–2878. doi: 10.1152/jn.00783.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Q, Jacovina AT, Deora A, Febbraio M, Simantov R, Silverstein RL, Hempstead B, Mark WH, Hajjar KA. Annexin II regulates fibrin homeostasis and neoangiogenesis in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:38–48. doi: 10.1172/JCI200419684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menell JS, Cesarman GM, Jacovina AT, McLaughlin MA, Lev EA, Hajjar KA. Annexin II and bleeding in acute promyelocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904013401303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Matsui H, Shiraiwa T, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Takahashi E, Kashiwayanagi M. Decreases in pheromonal responses at the accessory olfactory bulb of mice with a deficiency of the alpha1B or beta3 subunits of voltage-dependent Ca2+-channels. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:437–442. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Nakagawasai O, Yanai K, Nunoki K, Tan-No K, Tadano T, Iijima T. Modified behavioral characteristics following ablation of the voltage-dependent calcium channel beta3 subunit. Brain Res. 2007;1160:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi S, Nakajima Y, Masu M, Ueda Y, Nakahara K, Watanabe D, Yamaguchi S, Kawabata S, Okada M. Glutamate receptors: brain function and signal transduction Brain. Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;26:230–235. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nose K, Shibanuma M. Induction of early response genes by hypergravity in cultured mouse osteoblastic cells (MC3T3-E1) Exp Cell Res. 1994;211:168–170. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohya S, Tanaka M, Oku T, Asai Y, Watanabe M, Giles WR, Imaizumi Y. Molecular cloning and tissue distribution of an alternatively spliced variant of an A-type K+ channel alpha-subunit, Kv4.3 in the rat. FEBS Lett. 1997;420:47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01483-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossovskaya VS, Bunnett NW. Protease-activated receptors: contribution to physiology and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:579–621. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Suh YS, Kim H, Rhyu IJ, Kim HL. Chromosomal localization and neural distribution of voltage dependent calcium channel beta 3 subunit gene. Mol Cells. 1997;7:200–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompeiano O, d’Ascanio P, Balaban E, Centini C, Pompeiano M. Gene expression in autonomic areas of the medulla and the central nucleus of the amygdala in rats during and after space flight. Neuroscience. 2004;124:53–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragg H, Preibisch G. Structure and expression of the gene coding for the human serpin hLS2. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:12129–12134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmann H, Slenzka K, Kortje KH, Hilbig R. Synaptic plasticity and gravity: ultrastructural, biochemical and physicochemical fundamentals. Adv Space Res. 1992;12:63–72. doi: 10.1016/0273-1177(92)90265-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche KW, Standley S, McCallum J, Ly CD, Ehlers MD. Molecular determinants of NMDA receptor internalization. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:794–802. doi: 10.1038/90498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar P, Sarkar S, Ramesh V, Hayes BE, Thomas RL, Wilson BL, Kim H, Barnes S, Kulkarni A, Pellis N, Ramesh GT. Proteomic analysis of mice hippocampus in simulated microgravity environment. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:548–553. doi: 10.1021/pr050274r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar P, Sarkar S, Ramesh V, Kim H, Barnes S, Kulkarni A, Hall JC, Wilson BL, Thomas RL, Pellis NR, Ramesh GT. Proteomic analysis of mouse hypothalamus under simulated microgravity. Neurochem Res. 2008 May 13; doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9738-1. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M, Schaller M, Ginsberg M. Integrins: emerging paradigms of signal transduction. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:549–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson FA, Cousins SL, Kenny AV. Assembly and forward trafficking of NMDA receptors. Mol Membr Biol. 2008;25:311–320. doi: 10.1080/09687680801971367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suo Z, Wu M, Citron BA, Gao C, Festoff BW. Persistent protease-activated receptor 4 signaling mediates thrombin-induced microglial activation. Biol Chem. 2003;278:31177–31183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardy-Poncet B, Tardy B, Laporte S, Mismetti P, Amiral J, Piot M, Reynaud J, Campos L, Decousus H. Poor anticoagulant response to tissue factor pathway inhibitor in patients with venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:507–510. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Q, Menon AG, Stockand JD. Functional polymorphisms in the alpha-subunit of the human epithelial Na+ channel increase activity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F821–F827. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00312.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traina G, Bernardi R, Rizzo M, Calvani M, Durante M, Brunelli M. Acetyl-L-carnitine up-regulates expression of voltage-dependent anion channel in the rat brain. Neurochem Int. 2006;48:673–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uno Y, Horii A, Uno A, Fuse Y, Fukushima M, Doi K, Kubo T. Quantitative changes in mRNA expression of glutamate receptors in the rat peripheral and central vestibular systems following hypergravity. J Neurochem. 2002;81:1308–1317. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeber J, Levy M, Sampson MJ, Anflous K, Armstron DL, Brown SE, Sweatt JD, Craigen WJ. The role of mitochondrial porins and the permeability transition pore in learning and synaptic plasticity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18891–18897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westrick RJ, Bodary PF, Xu Z, Shen YC, Broze GJ, Eitzman DT. Deficiency of tissue factor pathway inhibitor promotes atherosclerosis and thrombosis in mice. Circulation. 2001;103:3044–3046. doi: 10.1161/hc2501.092492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka R, Soga K, Wakabayashi K, Takeba G, Hoson T. Hypergravity-induced changes in gene expression in Arabidopsis. Biol Sci Space. 2001;15:260–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LR. Effects of orbital space flight on vestibular reflexes and perception. Acta Astronaut. 1995;36:409–413. doi: 10.1016/0094-5765(95)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GS, Mehringer JH, Van Deerlin VMD, Kozak CA, Tollefsen DM. Murine heparin cofactor II: purification, cDNA sequence, expression and gene structure. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3632–3642. doi: 10.1021/bi00178a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao WQ, Waisman DM, Grimaldi M. Specific localization of the annexin II heterotetramer in brain lipid raft fractions and its changes in spatial learning. J Neurochem. 2004;90:609–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00221-008-1523-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.