Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Cardiovascular diseases account for nearly 20% of all hospitalizations in Canada and consume 12% of the total cost of all illnesses. With increasing trends of cardiovascular disease and increasing costs of care, development of cost-effective strategies is vital. The Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) trial demonstrated the effectiveness of clopidogrel plus acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) compared with ASA alone in reducing cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndromes and, in addition, patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in CURE (PCI-CURE) trial.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel in the Canadian health care system.

METHODS:

Estimates of hospitalization costs were based on the 2003 cost schedules released by the Health Funding and Costing Branch of the Alberta Health and Wellness, as well as on the Case Mix Group classification system. Life expectancy beyond the trial was estimated from the Saskatchewan Health Database. Cost-effectiveness was expressed as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, and bootstrap methods were used to estimate the joint distribution of costs and effectiveness.

RESULTS:

Clopidogrel was shown to be cost-effective, with incremental cost-effectiveness ratios less than $10,000 per event prevented and less than $4,000 per life-year gained. The probability of clopidogrel resulting in cost per life-year gained of less than $20,000 was 0.975 for CURE patients and 0.904 for PCI-CURE patients.

CONCLUSIONS:

The economic analysis demonstrated that clopidogrel combination therapy is not only cost-effective as antiplatelet therapy compared with ASA alone, but it is also cost-effective compared with other commonly used and openly reimbursed cardiovascular therapies in the Canadian health care system.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndromes, Antiplatelet therapy, Case Mix Group classification, Cost-effectiveness, Outcomes

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Les maladies cardiovasculaires représentent près de 20 % de toutes les hospitalisations au Canada et grugent 12 % du coût total de toutes les maladies. Étant donné la tendance croissante à souffrir de maladies cardiovasculaires et les coûts croissants des soins, il est essentiel d’élaborer des stratégies rentables. L’essai CURE sur le clopidogrel en cas d’angine instable pour prévenir les événements récurrents a démontré l’efficacité du clopidogrel ajouté à l’acide acétylsalicylique (ASA) par rapport à l’ASA seul pour réduire les événements cardiovasculaires chez les patients atteints de syndromes coronariens aigus ainsi que chez ceux subissant une intervention coronaire percutanée dans l’essai CURE avec interventions coronaires percutanées (PCI-CURE).

OBJECTIF :

Évaluer la rentabilité du clopidogrel au sein du système de santé canadien.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

L’évaluation des frais d’hospitalisation se fondait sur le barème des coûts de 2003 publié par la division du financement et des dépenses en santé du ministère de la Santé et du Mieuxêtre de l’Alberta, de même que sur le système de classification par groupes de maladies analogues. L’espérance de vie après l’essai était extrapolée de la base de données de santé de la Saskatchewan. La rentabilité était exprimée sous forme de rapport différentiel coût-efficacité, et les auteurs ont utilisé les méthodes d’autoamorçage pour évaluer la répartition conjointe des coûts et l’efficacité.

RÉSULTATS :

Le clopidogrel était rentable, selon des rapports différentiels coût-efficacité inférieurs à 10 000 $ par événement prévenu et moins de 4 000 $ de vie-année gagnée. La probabilité que le clopidogrel assure un coût de vie-année inférieur à 20 000 $ était de 0,975 pour les patients de l’essai CURE et de 0,904 pour les patients de l’essai PCI-CURE.

CONCLUSIONS :

L’analyse économique a démontré que la thérapie mixte de clopidogrel n’est pas seulement rentable à titre de thérapie antiplaquettaire par rapport à l’ASA utilisé seul, mais également par rapport à d’autres thérapies utilisées couramment et ouvertement remboursées au sein du système de santé canadien.

Cardiovascular diseases accounted for 18% of all hospitalizations in Canada in 2000 to 2001, a higher percentage than any other health problem. Hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease and stroke are projected to increase over the next 20 years, in part due to increased longevity of the population. Cardiovascular diseases were the leading cause of death in Canada in 1999, accounting for 36% of health-related deaths. An analysis of the number of coronary angioplasties between 1995 and 2001 revealed a 36% increase in procedures in that time frame (1).

The total economic burden of cardiovascular diseases on the Canadian health care system was estimated to be $18.5 billion in 1998 – nearly 12% of the total cost of all illnesses. Of this total, $4.2 billion included direct costs for hospitalization, $1.8 billion for drugs and $822 million for physician care. The major indirect costs included costs due to premature death ($8.2 billion) and morbidity due to short- or long-term disabilities ($3.4 billion). With predicted increasing trends of cardiovascular disease and increasing costs of care, the development of cost-effective therapies is a vital and necessary component of the health care industry (1).

The Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) trial was designed to compare the safety and efficacy of the long-term (one year) use of clopidogrel plus acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) with those of ASA alone in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and no ST segment elevation (2,3); in addition, a subset of these patients underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) during the course of the trial. The trial demonstrated the benefit of clopidogrel in reducing cardiovascular events, and subsequent economic studies demonstrated clopidogrel’s cost-effectiveness (4,5). The purpose of the present study was to determine the long-term cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel plus ASA relative to ASA alone in the Canadian health care system.

METHODS

Design of the CURE trial

The CURE trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing clopidogrel plus ASA with placebo plus ASA in patients who presented with ACS without ST segment elevation. Between December 1998 and September 2000, 12,562 patients were recruited at 482 centres in 28 countries. Of these, 1761 patients (14%) were Canadian. Patients were eligible if they were hospitalized within 24 h of the onset of symptoms of ACS and did not have significant ST segment elevation. Patients randomly assigned to clopidogrel plus ASA (n=6259) received a 300 mg loading dose of clopidogrel plus 75 mg ASA, followed by 75 mg of clopidogrel and 75 mg to 325 mg ASA daily for up to one year (Figure 1). The primary outcome of the trial was the composite of death due to cardiovascular cause, stroke or nonfatal MI.

Figure 1).

Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) trial design. ASA Acetylsalicylic acid; mo Months; R Random assignment

PCI-CURE study

The PCI-CURE study was a planned analysis of the efficacy of clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI during the course of the CURE trial (3). Of the 12,562 randomly assigned CURE patients, 2658 underwent PCI during the CURE trial and were included in the PCI-CURE study. Seventeen per cent (n=454) of these patients were Canadian. A total of 1345 patients were randomly assigned to placebo and 1313 patients were randomly assigned to clopidogrel. The timing of PCI was at the physician’s discretion; approximately two-thirds of patients (n=909 placebo, n=821 clopidogrel) underwent PCI during the initial hospitalization. At the time of PCI, the study drug was interrupted and open-label therapy was initiated for two to four weeks, after which time the blinded study drug was continued until the end of the follow-up, ranging from three to 12 months (nine months average). At the physician’s discretion, patients received conventional treatments, including thrombolytic agents, heparin, diuretics, antianginal therapy, antihypertensive medication and cholesterol-reducing agents. The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists, while discouraged in the CURE trial except for use in patients with refractory ischemia, was allowed during PCI.

Canadian economic analysis

A previous economic analysis demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel in five countries, including Canada (5). In that study, Canadian costs were based on those from a single institution. The main objective of the present economic analysis was to determine patient-level costs of the therapies used in the trial based on the Canadian Case Mix Group (CMG) classification system, and then to compare the respective costs of the clopidogrel arm (clopidogrel plus ASA) with the placebo arm (placebo plus ASA).

If the cost of the clopidogrel arm was greater, then a cost-effectiveness analysis was to be performed because the effectiveness of clopidogrel had been demonstrated. Costs included in the analysis were direct medical costs for hospitalization and drug costs in Canada. No data were available from the trial to calculate indirect costs due to lost productivity and they were therefore excluded from the present analysis.

Cardiovascular health care resource use and all follow-up hospitalizations were recorded prospectively, including diagnostic tests, therapeutic procedures and medications. Information on ambulatory care, including outpatient diagnostic procedures and testing (other than coronary angiography), was not recorded. Because the majority of resource-intensive procedures and tests were performed while patients were hospitalized, it is likely that most of the major components of health care resource use were collected. Possible exceptions included same-day testing not requiring hospitalization, such as nuclear imaging studies or echocardiograms, and nursing home and rehabilitation stays following stroke. The increased frequency of cardiovascular events in the placebo arm suggests that this is a conservative approach, because the analysis was biased in favour of the placebo arm.

Costing

Direct medical costs for hospitalization were based on the CMG classification system used by Canadian provinces, primarily for budgetary purposes and resource allocation. In the CMG system, the ‘most responsible diagnosis’ is the primary driver for costing. The ‘most responsible diagnosis’ is defined as the diagnosis at discharge that was most responsible for use of the most bed-days by the patient. In addition, groups are classified into complexity subgroups that take into account comorbid conditions and complications that impact the hospital length of stay and resource use. They range from a complexity level of 1, in which no complexity is noted, to a level of 4, in which the patient has a potentially life-threatening condition. Complications are dealt with on an individual basis, so it is possible that a patient may be assigned more than one CMG classification. Estimates of hospitalization costs were thus made from the CMG classification a CURE or PCI-CURE patient was likely to have been assigned.

The collection and reporting of costing based on the CMG system for hospitals vary widely across provinces. It was therefore necessary to select a province that provided sufficient detail to make the most accurate estimates of costs. Alberta and Ontario provide case cost data used by the Canadian Institute for Health Information to develop relative weights for CMG classifications; thus, the choice was between these two provinces. Alberta reported data at the most detailed level and was selected as the main source for costing.

Estimates of hospitalization costs were based on the 2003 cost schedules released by the Health Funding and Costing Branch of Alberta Health and Wellness (6). The case cost data released in this report represented the latest inpatient costs available for Alberta and provide case costs by CMG reported in 2002 Canadian dollars based on a blending of hospitalized cases from Alberta’s regional health authorities from 2000 to 2002. These costs were converted to 2002 values more reflective of the national average of case costs for Canada using a ratio based on provincial and national weighted inpatient costs per case for fiscal year 2000/01 provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information and reported by the Institute of Health Economics (7). Based on these data, it was estimated that the average Canadian inpatient case was 99% the cost of a case in Alberta. Estimated costs were then applied to patients in the CURE trial and reported in 2004 Canadian dollars, obtained by inflating older estimates using the inflation index for health care supplied by Statistics Canada (8).

The 2004 cost of clopidogrel was $2.40 per 75 mg dose. The cost of ASA varied widely, depending on dose and whether the cost source was the provincial formulary price of prescription ASA (excluding pharmacy markup) or the retail price of over-the-counter ASA. Thus, separate analyses were performed using a cost of $0.05 per tablet and another using a cost of $0.09 per tablet.

Life expectancy estimation

Life expectancy for patients with and without nonfatal events was estimated from the Saskatchewan Health Database (9,10). This database contains comprehensive longitudinal health care use data for the entire population of Saskatchewan, including data on 15,956 patients with acute MI and 18,704 patients with ischemic stroke.

Mean survival beyond the end of the trial was estimated by integrating the survival curves and adjusting for various patient characteristics, including experience of specific subsequent ischemic events (10). Cox proportional hazards models for each time period were derived for patients with covariates of age, diabetes, previous MI, previous stroke, prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) and hyperlipidemia. The cumulative survival functions over time were derived by applying the hazard function in sufficiently brief intervals so that the hazard rate can be assumed to be constant over the given period.

Sex- and age-specific estimates of life-years lost due to events were obtained by subtracting life expectancy estimates for individuals with a given event pattern from life expectancy estimates for individuals with no events. These estimates were then applied to the CURE patient population. For patients who experienced multiple events, lost life expectancy was estimated assuming a hierarchy of death, stroke and MI. It was assumed that clopidogrel would be stopped at the end of the trial and that there would be no further reduction or increase in nonfatal events between the two arms. The difference in average life-years lost due to events between the two arms, placebo minus clopidogrel, gives an estimate of life-years gained with clopidogrel. Cost and life expectancies were discounted 3% annually after the first year.

Cost-effectiveness

The cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel was expressed as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). The ICER is equal to the mean difference in costs of the two arms; in this case, the added cost of clopidogrel, divided by the difference in mean effectiveness. In the present analysis, effectiveness was expressed as event prevented (ep), which is the absolute risk reduction, and as life-years gained (lyg), which is the difference in life-years lost (LYL). The ICER per event prevented is calculated as follows:

where μΔ represents the mean difference.

The ICER per life-years gained is calculated as follows:

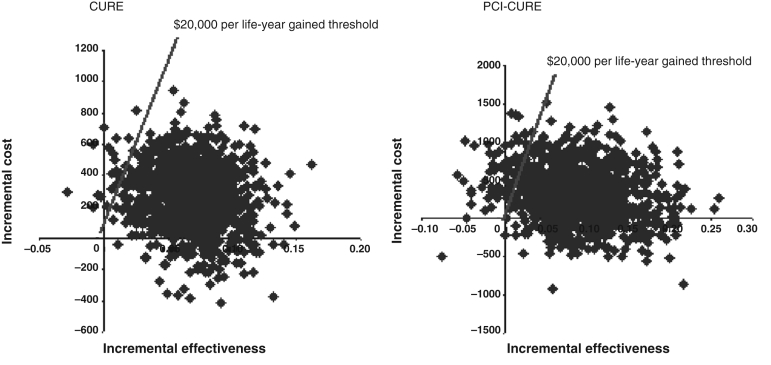

Because the cost-effectiveness ratio typically does not have a normal distribution, bootstrap methods (11) with 5000 replicates (with replacement) were used to estimate the distribution of costs and the ICERs. The joint distribution of cost and effectiveness was plotted in the cost-effectiveness plane. Quadrant I in the cost-effectiveness plane indicates cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel (greater cost, but more effective). Quadrant II indicates the dominance of clopidogrel (less cost, but more effective). Quadrant III is also cost-effective (less cost, but less effective). Quadrant IV indicates dominance of placebo over clopidogrel (greater cost and less effective). A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve was plotted for a range of cost-effective thresholds ranging from $0 to $100,000. The cost-effective threshold for the present study was $20,000, ie, clopidogrel was considered cost-effective if the cost of preventing one event per year or adding one year of life was less than $20,000.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed by reducing life expectancy gains by 50% and by 80%. Life expectancy was also estimated from the Framingham Heart Study database (12,13). The Framingham Heart Study, initiated in 1948, was designed as a longitudinal investigation of constitutional and environmental factors influencing the development of cardiovascular disease in men and women free from these conditions at the outset. The first person was examined in September 1948 and four years later, 5209 persons had received their first examination. The group has now been followed in the study for 24 subsequent biennial examinations. Finally, the higher cost of ASA ($0.09 per tablet) was considered in a sensitivity analysis.

RESULTS

Summary of the CURE trial

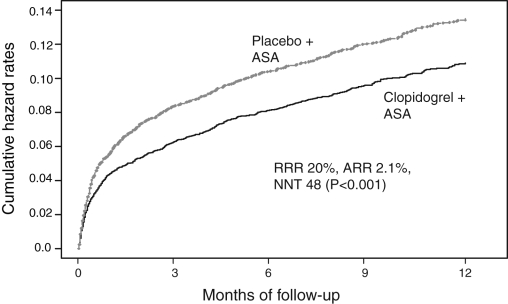

Table 1 presents a summary of the major clinical events from random assignment to the end of follow-up for the clopidogrel and placebo arms. At one-year follow-up, the event rate in the clopidogrel arm was 9.3% compared with 11.4% in the placebo arm – an absolute risk reduction of 2.1% (P<0.001). Figure 2 plots the cumulative hazard rates over one year. The magnitude of benefit of clopidogrel plus ASA was consistent across low-, intermediate-and high-risk patients. While there was a significantly greater incidence of major bleeding in the clopidogrel plus ASA group (P=0.002), the majority of events occurred in patients undergoing an invasive procedure and was also associated with higher doses of ASA. Of importance, there was no significant difference in bleeding rates between arms when clopidogrel was stopped more than five days before CABG. By comparison, the number of vascular events prevented per 1000 patients was much greater than the number of major bleeding events over the one-year follow-up.

TABLE 1.

Summary of clinical data from the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) trial

| Clopidogrel (n=6259) | Placebo (n=6303) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 64±11 | 64±11 | 0.7448 |

| Female sex, % | 39 | 38 | 0.6450 |

| Myocardial infarction at presentation, % | 26 | 26 | 0.6098 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, % | 32 | 32 | 0.6314 |

| Diabetes, % | 22 | 23 | 0.5920 |

| Hypertension, % | 60 | 58 | 0.0168 |

| Clinical outcomes in economic study, % | 9.3 | 11.4 | <0.0001 |

| Death (any cause) | 5.8 | 6.2 | 0.2779 |

| Myocardial infarction | 5.2 | 6.7 | 0.0004 |

| Stroke | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.3532 |

| Bleeding, major or life threatening, % | 3.7 | 2.7 | 0.0015 |

| Major | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.0020 |

| Life-threatening | 2.1 | 1.7 | 0.1000 |

| Major and life-threatening | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.9999 |

| Minor bleeding, % | 5.1 | 2.4 | <0.0001 |

Figure 2).

Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events trial design (CURE) trial results. ASA Acetylsalicylic acid; ARR Absolute risk reduction; NNT Number needed to treat; RRR Relative risk reduction

PCI-CURE study

At one-year follow-up, the event rate in the PCI-CURE clopidogrel arm was 9.6% compared with 13.2% in the placebo arm – an absolute risk reduction of 3.6% (P<0.002). The two treatment groups were well balanced with regard to the timing of PCI. Sixty-five per cent of interventions were performed during the initial hospitalization at a median time of six days after random assignment for both groups, and 35% of interventions were performed after discharge from the initial hospitalization, at a median time of 49 days after random assignment (3). There was no difference between treatment groups in age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, prior history of CABG or PCI, or present or previous MI for the overall population (3) or the early PCI subgroup (results not shown). The majority of patients received an intracoronary stent (82% clopidogrel, 81% placebo), and open-label thienopyridine was used in more than 80% of patients in both treatment arms following PCI.

Costs and estimation of life-years gained

Table 2 lists the most common CMGs used in calculating hospitalization costs of CURE patients along with complexity level, average length of stay, average cost per patient, as well as the number of initial hospitalizations in the clopidogrel and placebo arms. Table 3 summarizes the clopidogrel and placebo differences in costs, event rates and long-term estimates of life-years lost for CURE and PCI-CURE patients. Costs for clopidogrel were higher than for placebo, and event rates were higher in placebo patients. Estimated lost life-years were higher for placebo patients, resulting in life expectancy gains with clopidogrel. CURE patients in the clopidogrel arm were estimated to have gained an average of 0.0682 life-years (95% CI 0.0122 to 0.1190). For PCI-CURE patients, the average gain was 0.0885 life-years (95% CI −0.0082 to 0.1842).

TABLE 2.

Case Mix Group (CMG), complexity, and average length of stay (LOS) and cost per patient

| CMG | CMG description | Complexity level | Average LOS per case, days | Average cost per patient, $ | Number of initial hospitalizations

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clopidogrel | Placebo | |||||

| 13 | Specific cerebrovascular disorders, except transient ischemic attack | All | 9.8 | 8,029 | 5 | 5 |

| 143 | Simple pneumonia and pleurisy | 1 | 4.7 | 3,107 | 0 | 2 |

| 178 | Coronary artery bypass with heart pump and cardiac catheterization | 3 | 19.1 | 29,357 | 6 | 11 |

| 181 | Other CT procedures with heart pump and cardiac catheterization | All | 8.7 | 24,105 | 0 | 0 |

| 188 | PTCA with complicating cardiac conditions | All | 3.4 | 9,363 | 793 | 876 |

| 186 | Permanent pacemaker implant without specified cardiac conditions | All | 5.3 | 17,851 | 0 | 0 |

| 183 | Major CT procedures without heart pump but with cardiac catheterization | All | 5.3 | 10,819 | 44 | 56 |

| 200 | AMI, unstable angina or cardiac catheterization with shock or PE | 4 | 8.5 | 10,122 | 140 | 163 |

| 208 | AMI without cardiac catheterization or specified cardiac conditions | All | 5.3 | 5,116 | 1247 | 1231 |

| 210 | Unstable angina with cardiac catheterization and specified cardiac conditions | All | 8.8 | 9,050 | 742 | 684 |

| 222 | Heart failure | All | 8.4 | 5,646 | 0 | 0 |

| 237 | Arrhythmia | 4 | 12.9 | 13,150 | 0 | 0 |

| 229 | Atherosclerosis | 1 | 5.7 | 4,108 | 13 | 10 |

| 213 | Unstable angina without cardiac catheterization or specified cardiac conditions | All | 3.8 | 2,878 | 2759 | 2710 |

| 242 | Chest pain | All | 2.7 | 2,231 | 0 | 0 |

AMI Acute myocardial infarction; CT Computed tomography; PE Pulmonary embolism; PTCA Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty

TABLE 3.

Cost, event rates and long-term estimates of life-years lost

| Trial | Clopidogrel | Placebo | Δ | Δ95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost, $ | CURE | 12,423 | 12,160 | 263 | −146–649 |

| PCI-CURE | 15,210 | 14,877 | 333 | −343–1,019 | |

| Event rate | CURE | 0.093 | 0.114 | 0.021 | 0.0104–0.0317 |

| PCI-CURE | 0.096 | 0.132 | 0.036 | 0.0115–0.0597 | |

| Lost life-years | CURE | 0.3910 | 0.4592 | 0.0682 | 0.0122–0.1190 |

| PCI-CURE | 0.3337 | 0.4222 | 0.0885 | −0.0082–0.1842 |

The change in event rate and lost life-years equals placebo minus clopidogrel values. CURE Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events; PCI-CURE Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in CURE

Cost-effectiveness

For CURE patients, total one-year cost was $12,423 for the clopidogrel arm and $12,160 for the placebo arm – an additional cost for the clopidogrel arm of $263. The difference in cost divided by the difference in event rates (0.021) resulted in an ICERep of $12,524 per year. For PCI-CURE patients, the one-year cost for clopidogrel was $15,210 and $14,877 for placebo, an additional cost for clopidogrel of $333. Thus, the PCI-CURE ICERep was $9,250 ($333/0.036).

Table 4 presents the ICERlyg for CURE and PCI-CURE patients along with the per cent of bootstrap replications of cost and effectiveness in quadrants II and IV of the cost-effectiveness plane and the percentage of bootstrap replications less than $20,000. For both CURE and PCI-CURE, the ICERs per life-year gained were less than $4,000. Figure 3 plots the joint distribution of the 5000 bootstrap replications of cost and effectiveness for CURE and PCI-CURE. Most of the bootstrap pairs fell into quadrant I. Nine per cent fell into quadrant II (dominant) and one-half a per cent fell into quadrant IV (dominated) for CURE. For PCI-CURE, nearly 17% were dominant and 3% were dominated. Figure 4 plots the cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for CURE and PCI-CURE. The probabilities of bootstrap estimates less than the $20,000 per life-year gained threshold are indicated by the vertical line, which intersects the CURE curve at 0.975 and the PCI-CURE curve at 0.904.

TABLE 4.

Cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel

| Patients | Δcost, $ | Δlost life-years | ICERlyg, $ | Per cent dominant | Per cent dominated | Per cent <$20,000/lyg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CURE | 263 | 0.0682 | $3,856 | 9.1 | 0.5 | 97.5 |

| PCI-CURE | 333 | 0.0885 | $3,763 | 16.6 | 2.9 | 90.4 |

CURE Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events; ICER Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; lyg Life-years gained; PCI-CURE Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in CURE

Figure 3).

Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in CURE (PCI-CURE) trials cost-effectiveness scatterplots

Figure 4).

Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in CURE (PCI-CURE) trials cost-effectiveness acceptability curves

Sensitivity analyses

Using Framingham data, CURE patients in the clopidogrel arm were estimated to have gained an average of 0.0699 life-years (95% CI −0.0077 to 0.1440), and for PCI-CURE patients, the average gain was 0.0698 (95% CI −0.0375 to 0.1788) life-years. Thus, the ICERlyg for CURE was $3,763 ($263/0.0699), and for PCI-CURE was $4,771 ($333/0.0698). The percentage of bootstrap replications less than $20,000 was 92.8% for CURE and 82.2% for PCI-CURE.

Because the analysis of life-years gained requires the use of external databases to project life expectancy beyond the trial period, actual life expectancies, if patients are followed past the trial period, may be either larger or smaller than projected. If the estimated gain in life expectancy were only half of that projected, then the CURE ICERlyg would be $7,713. If the estimated gains were only 20% of those projected, the ICERlyg would be $19,338. For PCI-CURE, a 50% reduction in life expectancy would result in an ICERlyg of $7,517, and an 80% reduction would result in an ICERlyg of $18,814.

Assuming a cost of $0.09 per ASA tablet added less than $200 to the ICERs per life-year gained. This was true for both CURE and PCI-CURE.

DICUSSION

For patients with ACS, long-term antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel in addition to ASA is highly cost-effective in the Canadian health care system. This was also true for the subset of patients undergoing PCI during the trial. Both the ICERep ($12,524) and the ICERlyg ($3,856) were well below an acceptable cost-effective threshold of $20,000. Over 92% of the bootstrap samples were less than $20,000 for both models. The results remained favourable even when life expectancies were assumed to be only 20% of those projected – the corresponding ICERlyg was still less than $20,000.

Although CURE showed that clopidogrel plus ASA was highly effective compared with ASA alone, there have been questions raised by some reimbursement decision makers as to whether clopidogrel plus ASA is also cost-effective. Compared with other therapies for ACS patients, the cost effectiveness of clopidogrel appears to be highly competitive. Beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and lipid-lowering therapies, all standard therapies, incur a higher cost per life-year gained than clopidogrel (14–16). In this analysis, the cost of an extra year of life post-ACS, with clopidogrel plus ASA, was approximately five times lower than a $20,000 threshold of cost-effectiveness.

Clopidogrel has also been shown to be cost-effective in other health care systems. A United States economic analysis of CURE estimated ICERs per life-year gained that ranged from US$8,000 to US$9,000, depending on costing methods (4), which is well below any accepted willingness-to-pay threshold. ICERep was also demonstrated for several countries, including Canada (5). The ICERep was higher in the present study ($12,423 versus $7,973), reflecting differences in costing methods. Nevertheless, both ICERs demonstrate cost-effectiveness well below generally accepted thresholds.

Limitations

CURE was a multinational trial, and the approach of costing in the Canadian health care system does not fully account for possible differences in treatment practices and resource use between countries or health care systems. Nevertheless, the costing of hospitalizations should yield unbiased overall cost estimates in both arms, unless costs within a particular CMG category are higher in one arm (although there is no reason to believe that this is the case).

No outpatient treatment, rehabilitation or nursing home resource use information was collected in the CURE trial and was thus excluded from the present analysis. Given that these costs may be expected to be higher in the placebo arm due to the higher in-trial nonfatal event rate, this analysis is a conservative estimate of incremental cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel plus ASA over ASA alone.

Another potential limitation of the study is the fact that external databases were used to estimate life expectancies; therefore, the similarity of the patients in the trial and the databases is always open to question. The fact that the two databases yielded similar results offers reassurance that the estimates used in this analysis are reasonable.

CONCLUSIONS

The CURE trial demonstrated a significant effect in the reduction of cardiovascular events over a one-year period with the use of clopidogrel for ACS patients and those undergoing PCI. The economic analysis demonstrated that clopidogrel combination therapy is not only cost-effective as antiplatelet therapy compared with ASA alone, but it is also cost-effective compared with other commonly used and openly reimbursed cardiovascular therapies in the Canadian health care system.

Footnotes

DISCLAIMER: Contract of Bristol-Myers Squibb/sanofi Canada Partnership with Emory University (Atlanta, Georgia).

REFERENCES

- 1.Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada The growing burden of heart disease and stroke in Canada, 2003. <www.cvdinfobase.ca/cvdbook> (Version current at September 26, 2007).

- 2.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK, Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events trial Investigators Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation N Engl J Med 2001345494–502.(Errata in 2001;345:1506, 2001;345:1716). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, et al. Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events trial (CURE) Investigators Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: The PCI-CURE study. Lancet. 2001;358:527–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weintraub WS, Mahoney EM, Lamy A, et al. CURE Study Investigators Long-term cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel given for up to one year in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:838–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamy A, Jönsson B, Weintraub WS, et al. The CURE Economic Group The cost-effectiveness of the use of clopidogrel in acute coronary syndromes in five countries based upon the CURE study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11:460–5. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000152239.28456.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health Funding and Costing Branch, Alberta Health and Wellness Health costing in Alberta, 2003 − annual report<www.health.gov.ab.ca/resources/publications/Health_Costing_2003.pdf> (Version current at September 26, 2007).

- 7.The Institute of Health Economics Provincial and national cost per weighted case for inpatient services for fiscal year 2000/1. <www.ihe.ca/documents/ihe/publications/phcc/prov_cost/cihi.html> (Version current at September 26, 2007).

- 8.Statistics Canada Latest release from the Consumer Price Index. <www.statscan.ca>.

- 9.Downey W, Beck P, McNutt M, Stang MR, Osei W, Nichol J. Health databases in Saskatchewan. In: Strom BL, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. 3rd edn. Chichester: Wiley; 2000. pp. 325–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Migliaccio-Walle K. Estimating survival for cost-effectiveness analyses: A case study in atherothrombosis. Value Health. 2004;7:627–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.75013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peeters A, Mamun AA, Willekens F, Bonneux L. A cardiovascular life history. A life course analysis of the original Framingham Heart Study cohort. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:458–66. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahoney EM, Jurkovitz CT, Chu H, et al. TACTICS-TIMI 18 Investigators Treat Angina with Aggrastat and Determine Cost of Therapy with an Invasive or Conservative Strategy – Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. Cost and cost-effectiveness of an early invasive vs conservative strategy for the treatment of unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2002;288:1851–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spaans JN, Coyle D, Fodor G, et al. Application of the 1998 Canadian cholesterol guidelines to a military population: Health benefits and cost effectiveness of improved cholesterol management. Can J Cardiol. 2003;19:790–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamy A, Yusuf S, Pogue J, Gafni A, Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Investigators Cost implications of the use of ramipril in high-risk patients based on the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study. Circulation. 2003;107:960–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000050600.49419.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canadian Coordinating Office of Health Technology Assessment HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors: A review of published clinical trials and pharmacoeconomic evaluations<www.cadth.ca/index.php/en/publication/26> (Version current at September 26, 2007). [PubMed]