Summary

Background

Pakistan carries one of the world’s highest burdens of chronic hepatitis and mortality due to liver failure and hepatocellular carcinomas. However, national level estimates of the prevalence of and risk factors for hepatitis B and hepatitis C are currently not available.

Methods

We reviewed the medical and public health literature over a 13-year period ([Au?1] 1994–September 2007) to estimate the prevalence of active hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C in Pakistan, analyzing data separately for the general and high-risk populations and for each of the four provinces. We included 84 publications with 139 studies (42 studies had two or more sub-studies).

Results

Methodological differences in studies made it inappropriate to conduct a formal meta-analysis to determine accurate national prevalence estimates, but we estimated the likely range of prevalence in different population sub-groups. A weighted average of hepatitis B antigen prevalence in pediatric populations was 2.4% (range 1.7–5.5%) and for hepatitis C antibody was 2.1% (range 0.4–5.4%). A weighted average of hepatitis B antigen prevalence among healthy adults (blood donors and non-donors) was 2.4% (range 1.4–11.0%) and for hepatitis C antibody was 3.0% (range 0.3–31.9% [Au?2]). Rates in the high-risk subgroups were far higher.

Conclusions

Data suggest a moderate to high prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in different areas of Pakistan. The published literature on the modes of transmission of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in Pakistan implicate contaminated needle use in medical care and drug abuse and unsafe blood and blood product transfusion as the major causal factors.

Keywords: Hepatitis, Hepatitis B virus, Hepatitis C virus, Pakistan, Injection

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are among the principal causes of severe liver disease, including hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis-related end-stage liver disease. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that there are 350 million people with chronic HBV infection and 170 million people with chronic HCV infection worldwide.1,2 Hepatitis B is estimated to result in 563 000 deaths and hepatitis C in 366 000 deaths annually.3 Given its large population (165 million) and intermediate to high rates of infection,1,2 Pakistan is among the worst afflicted nations.

Pakistan has one of the world’s highest fertility rates, exceeding four children per woman.4 Its approximately 800 000 sq km are slightly less than twice the size of the state of California in the USA and Pakistan is larger than either Turkey or Chile.4,5 Pakistan is divided into four provinces, Punjab, Sindh, Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP), and Balochistan, as well as federally administered areas including the capital (Islamabad), Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATAs), and the western third of Jammu and Kashmir.6,7 Considering Pakistan’s size and large, growing population, there is a surprising dearth of information about hepatitis prevalence, although more is known about its risk factors. We reviewed the medical and public health literature over a 13-year period for details on the prevalence of HBV and HCV in Pakistan, analyzing data separately for general and high-risk populations and for each of the four provinces. We further reviewed the published literature concerning the risk factors, including the major modes of transmission of HBV and HCV in Pakistan.

Methods

We initially identified the studies of interest from 1994 to 2007 (up to September 30, 2007) by search of the PubMed database of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health (USA), using two search strategies: [hepatitis AND Pakistan] and [(HBV OR HCV OR Blood Borne) AND Pakistan]. We also searched in Pakmedinet.com, a search engine that includes the non-indexed journals of Pakistan, by using the keywords [hepatitis or HBV or HCV]. We identified additional articles through searches of specific authors working in this field and through the cited references of relevant articles.

Abstracts of 903 articles were reviewed by one author (SAA) and 182 articles were identified based on the likelihood that primary data on the prevalence of chronic HBV or HCV in Pakistan were to be found within. Articles commenting on risk factors for transmission of hepatitis in Pakistan were also identified. Out of 182 articles, 23 could not be retrieved for complete review due to the obscure or unclear nature of the reference, though we included eight of these studies based on the relevant information available in the abstracts. We found 57 articles reporting primary data on the prevalence of chronic HBV and 63 articles reporting primary data on the prevalence of chronic HCV in Pakistan.

Detection of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) was considered the marker of chronic HBV and detection of hepatitis C virus antibody (HCVAb) was considered the marker of chronic HCV. Data from these articles regarding study time period, region (city and province), study population (general or high-risk), lab techniques used for HBsAg or HCVAb detection, total sample size, and percentages and numbers of HBV and HCV positive cases were extracted. Prevalence data from individual studies were further segregated into age groups or regions of the country if described in the study. Studies that included primarily but not exclusively adult data were still grouped with adults. Some studies had methodological features that could be criticized; they were included only if they provided the HBsAg or HCVAb data on a defined population using reliable laboratory methods. Based on the sample size of individual studies, simple Wilson binomial confidence intervals were calculated for each study,8 along with a naïve weighted average prevalence (weighted by each study’s sample size) in the general and high-risk populations. Due to methodological differences between studies and the very large sample sizes of a few studies, no formal statistical testing for differences between studies was carried out.

Results

HBV in general populations

Eight pediatric9–16 and 35 adult10,13,15,17–48 studies addressed the seroprevalence of chronic HBV infection in the general population of Pakistan using HBsAg in asymptomatic persons. The weighted average of all the studies in general pediatric populations was 2.4% (range 1.7–5.5%; Figure 1). Studies in adults were either conducted in blood bank donors17–37 or in a non-blood donor general population.10,13,15,38–48 Overall HBsAg seroprevalence was higher in the non-blood donor population (3.8% weighted average, range 1.4–11.0%) than the blood donor population (2.3% weighted average, range 1.4–8.4%; Figure 1). The overall HBsAg seroprevalence in healthy adults based on combined data from blood donors and non-donors was 2.4% (range 1.4–11.0%).

FIGURE 1. Summary of studies reporting HBV prevalence in the general population of Pakistan.

Each study is represented horizontally. From L-R: reference number, first author, city in which study conducted, year in which study published; Dot and bar represent the point prevalence of HBV with calculated 95% confidence interval; lab technique used to detect HBsAg; and sample size of the study. The vertical line represents the calculated weighted average prevalence of HBV based on all the studies in the particular group.

ELISA (#) =Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (# represents generation of test); RPHA=Reverse particle hemagglutination assay; ICT=Immuno-chromatographic test; LPA=Latex particle agglutination; MEIA (#)=Micro enzyme immunoassay (# represents generation of test); RIBA=Recombinant immunoblot assay; ??=unknown

Few studies have been published from Balochistan,15,39,43 NWFP,21,27,30,33,37,43,45 and rural parts of Sindh.18,48 Three small studies in Balochistan15,39,43 showed a higher prevalence of HBsAg (9.3% weighted average, range 3.9–11.0%) compared to other provinces (Figure 1). Wide variations in different areas within each province were again noted but no clear trends in prevalence rates were identified over time.

HCV in general populations

We found eight pediatric9,10,14,16,38,49–51 and 35 adult10,17,18,22–25,27–30,32–38,40–42,44–47,49,50,52–59 studies assessing HCVAb seroprevalence in general populations. The weighted average HCVAb seroprevalence in pediatric studies was 2.1% (range 0.4–5.4%). In the adults, studies of HCV seroprevalence in non-blood donors10,38,40–42,44–47,49,50,59 showed higher rates (5.4% weighted average, range 2.1–31.9%) than in blood donors17,18,22–25,27–30,32–37,52–58 (2.8% weighted average, range 0.5–20.7%; Figure 2). The overall HCV seroprevalence in healthy adults, based on combined data from blood donors and non-donors was 3.0% (range 0.5–31.9% [Au?2]).

FIGURE 2. Summary of studies reporting HCV prevalence in the general population of Pakistan.

Each study is represented horizontally. From L-R: reference number, first author, city in which study conducted, year in which study published; Cross and bar represent the point prevalence of HCV with calculated 95% confidence interval; lab technique used to detect HCVAb; and sample size of the study. The vertical line represents the calculated weighted average prevalence of HCV based on all the studies in the particular group.

ELISA (#) =Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (# represents generation of test); RPHA=Reverse particle hemagglutination assay; ICT=Immuno-chromatographic test; LPA=Latex particle agglutination; MEIA (#)=Micro enzyme immunoassay (# represents generation of test); RIBA=Recombinant immunoblot assay; ??=unknown

Punjab10,17,23–25,28,29,34,35,38,40–42,44–47,49,50,53,54,57,58 reports suggested a higher prevalence of HCV (4.3% weighted average, range 0.4–31.9%) compared to Sindh,18,22,32,45,52,56 Balochistan,55 and NWFP27,30,33,37,45,59 (Figure 2). Ten10,38,40–42,44,46,47,49,50 of 12 studies10,38,40–42,44–47,49,50,59 in non-blood donors were performed in Punjab. Wide variations in different areas within Punjab were noted (range 0.4–31.9%) and no clear trends were identified over time.

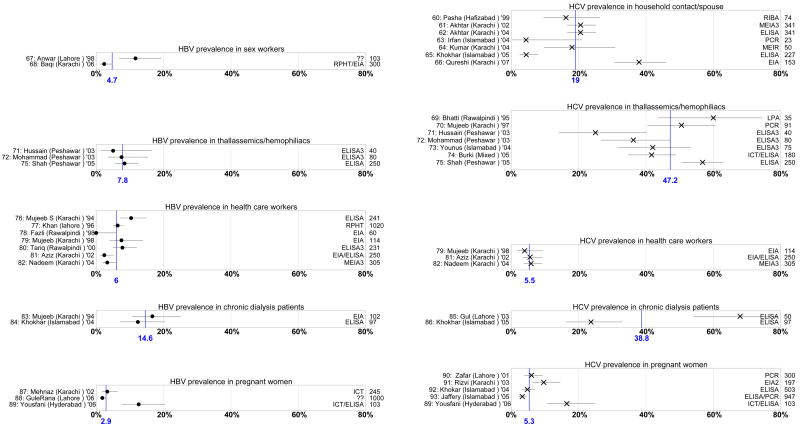

Prevalence of HBV and HCV in high-risk populations

Few studies have addressed the prevalence of HBsAg and HCVAb in the high-risk populations of Pakistan60–93 (Figure 3). Only one study in female sex workers67 and one study in male sex workers (hijras, some of whom are eunuchs)68 were found to address the HBV seroprevalence in this population (Figure 3). No HCV study in sex workers was identified. Studies in the household contacts of HCV infected patients60–66 showed a relatively high prevalence of HCV (19.0% weighted average, range 4.3–38.0%; Figure 3). In multi-transfused population of patients with thalassemia or hemophilia, three studies71,72,75 showed a moderately high prevalence of HBsAg (7.8% weighted average, range 5.0–8.4%), while seven studies69–75 showed a very high prevalence of HCVAb (47.2% weighted average, range 25–60%; Figure 3). Similarly, a high prevalence of HBsAg83,84 (14.6% weighted average, range 12.4–16.6%) and HCVAb85,86 (38% weighted average, range 23.7–68%) was described in the studies of patients undergoing chronic dialysis. Studies in healthcare workers showed relatively higher rates of HBV76–82 (6% weighted average, range 0–10.3%) and HCV79,81,82 (5.5% weighted average, range 4.0–5.9%, Figure 3) than in the general population (Figures 1 and 2). Studies in pregnant women showed similar rates of HBV87–89 (2.9% weighted average, range 1.8–12.6%; Figure 3), but higher rates of HCV89–93 (5.3% weighted average, range 3.2–16.5%; Figure 3), compared to the general population (Figures 1 and 2).

FIGURE 3. Summary of studies reporting HBV and HCV prevalence in the high risk population of Pakistan.

Each study is represented horizontally. From L-R: reference number, first author, city in which study conducted, year in which study published; Dot and bar represent the point prevalence of HBV with calculated 95% confidence interval while cross and bar represent point prevalence of HCV with calculated 95% confidence interval; lab technique used to detect HBsAg or HCVAb; and sample size of the study. The vertical line represents the calculated weighted average prevalence of HBV or HCV based on all the studies in the particular group.

ELISA (#) =Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (# represents generation of test); RPHA=Reverse particle hemagglutination assay; ICT=Immuno-chromatographic test; LPA=Latex particle agglutination; MEIA (#)=Micro enzyme immunoassay (# represents generation of test); RIBA=Recombinant immunoblot assay

Risk factors for HBV and HCV infection in Pakistan

Needles in healthcare settings

Injections in healthcare settings have been well described in the literature as a major mode of transmission of HBV and HCV in developing countries.94,95 A few well-controlled studies have demonstrated a relationship between therapeutic injections and the high prevalence of HBV and HCV.14,38,60,96–99 Khan et al. interviewed 203 adult patients as they left local clinics in a peri-urban community just outside of Karachi (Sindh), the major port city located in southern Pakistan.96 Of the patients, 81% received an injection on the day of interview. Of the 135 patients who provided a serum sample, 44% were HCVAb positive and 19% had antibodies against HBV (HBsAg was not measured). If oral and injectable medications were deemed equally effective, 44% of the patients declared that they would still prefer injectables. Unsterile, used needles were being used in 94% of the injections observed by the study team and none of the 18 practitioners knew that HCV could be transmitted by injections. In a case–control study in Hafizabad (Punjab), Luby et al. found that HCV infected patients were significantly more likely to have received five or more injections in the past 10 years compared to non-infected controls (odds ratio 5.4, confidence interval 1.2–28).38 In a study of household members of patients with HCV in Hafizabad (Punjab), Pasha et al. showed that the household members who had more than four injections per year were 11.9 times more likely to be infected than others (p = 0.02).60 Similarly, Usman et al. found that in patients with acute HBV, the attributable risk for therapeutic injections was 53%.97 Other studies by Jafri et al., Bari et al., Shazi and Abbas, and others have also shown similar results from diverse regions of Pakistan.14,98,99

Luby et al. in a follow-up study in Hafizabad showed that it is possible to improve the practice of unsterile and unnecessary injections by relatively simple community-based interventions.100 After low-cost community-based efforts to increase awareness, there was a reported decrease in the use of injections overall and an increase in the use of new needles for injections. The assumption that this will lead to decreased transmission of HBV and HCV makes logical sense, but has not been demonstrated.

Receipt of blood and blood products

Very high prevalence rates of HBV and HCV in multi-transfused populations are due to blood transfusions, but limited data are available about the practices of blood banks in Pakistan. Luby et al. studied 24 randomly selected blood banks in Karachi in 1995; while 95% had reagents and equipment to test for HBV, only 55% could screen for HIV and 23% for HCV.101 Fifty percent of blood banks regularly utilized paid blood donors and only 25% actively recruited voluntary blood donors. More recent data about the practices are not available. In 2001, Ahmed reported a higher prevalence of HBV in professional blood donors as compared to voluntary blood donors (9% vs. 0.8%, p < 0.001).102

Injection drug users (IDUs)

According to the year 2000 National Assessment Study of Drug Use in Pakistan supported by the United Nations Office of Drug Control and Crime Prevention (UNODC), there are 500 000 heroin addicts in Pakistan, of whom 75 000 (15%) are regular IDUs and 150 000 (30%) are occasional IDUs.103 Data on the disease burden in this large high-risk population are limited. Kuo et al., in a study conducted in 2003, showed HCV prevalence of 93% and 75% among IDUs of Lahore (Punjab) and Quetta (Balochistan), respectively,104 while Achakzai et al., in a smaller study in 2004, showed HBV, HCV, and HIV prevalences of 6%, 60%, and 24%, respectively, in the IDUs of Quetta.105 A year 2005 pilot survey of IDUs in Karachi (Sindh) showed an HIV prevalence of 26%, confirming the long-anticipated expansion of the HIV epidemic in Pakistan.106 HBV and HCV seroprevalence rates were not studied in this survey. A follow-up national survey in 2005 showed HIV prevalence of 23% and 0.5% and HCV prevalence of 88% and 91% in IDUs of Karachi (Sindh) and Lahore (Punjab), respectively.107

Occupational risks

Certain professions like healthcare workers, sex workers, and barbers may be at increased risk of getting HBV and HCV. The best studied amongst them in Pakistan are healthcare workers, showing a relatively higher prevalence (weighted average 6% and 5.5% for HBV and HCV, respectively) than in general population (Figures 1 and 2). The lack of universal immunization against HBV has been highlighted, especially in these high-risk populations, but coverage of HBV immunization has improved in the general population since 2003.108 According to the WHO–UNICEF estimates of 2005, 73% of the target population (infants <1 year) of Pakistan have been vaccinated for HBV.108 While trends are encouraging, coverage is still significantly lower than in industrialized countries. Its benefits on HBV incidence may not be apparent for many years, though eventually one would expect substantial benefit from the innovation of HBV vaccination among Pakistani infants.

Shaving by barbers

It has been suspected that barbers may be contributing to the spread of HBV and HCV by using contaminated razors for shaving. Janjua and Nizamy, in a cross-sectional study of barbers in Rawalpindi/Islamabad in 1999, showed that only 13% knew that hepatitis could be transmitted by contaminated razors.109 During the actual observation, razors were reused for 46% of shaves. It is possible that contaminated razors may be contributing in the transmission of HBV and HCV, but their relative importance is not clear.

Household contacts/spousal transmission

While some studies have shown a relatively higher prevalence in the household members of patients with HBV and HCV, other studies in the spouses of index cases have shown rates similar to controls.60–64 Pasha et al. showed the prevalence of HCV in household members of HCV patients to be 2.5 times that of the general population, but no routes of transmission within the household were associated.60 The international literature suggests that the sexual transmission of HCV is very low.110,111 It is likely that the high prevalence reported in household contacts in Pakistan may be due to the fact that they are exposed to the same community risk factors as the index patient, rather than intra-household transmission per se. In contrast, HBV intra-familial transmission is well documented outside of Pakistan, and HBV is far more infectious as compared to HCV or HIV.112–114

Discussion

We observed highly variable seroprevalence estimates for both HBV and HCV from different studies in similar populations, even within the same province. Unlike highly contagious diseases like measles that have a more predictable seroprevalence, blood-borne illnesses like hepatitis and HIV are transmitted sporadically or in micro-epidemics. These micro-epidemics may account for the wide variations in prevalence seen within a nation, a province, or even a community. Identification of the causes of these micro-epidemics provides an opportunity to limit the transmission of these diseases.115–117 However, methodological differences in sampling strategies may also contribute to differences in seroprevalence within similar regions or populations. For example, one study of the general population did a staged cluster random sampling of the entire city’s study population,14 while another study of putative ‘random samples’ in a different city recruited persons with the aid of newspaper advertisements50 that may have distorted the risk profile of respondents compared to the former study.

As seen in this review, studies of HBV and HCV prevalence are often conducted in blood donor populations because of convenience and access to a large sample size. However, these studies may not truly represent the general population. Prevalence in blood donors may be an underestimate of the population prevalence if potential donors with a high-risk profile, like history of jaundice, injection drug use, multiple sexual partners, etc. are screened out by questionnaires. Conversely, prevalence in blood donors may be an overestimate of the general population if professional blood donors were included, who are often injection drug users selling blood for money. Nonetheless, it is clear that both HBV and HCV infections are very common in Pakistan such that serious incidence rates of end-stage liver disease, both cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, will plague this nation for many years to come.

The published literature regarding risk factors for HBV and HCV transmission in Pakistan is informative. WHO estimates that in Southeast Asia, an average person receives four injections per year, most of which are unnecessary and up to 75% are unsafe or reused.118 Unnecessary injections are given commonly in Pakistan out of the prevalent view in the population that injected medicines are more effective than oral medications.119,120 Intramuscular injections are frequently used for fever, fatigue, and general ailments, while intravenous drips are used for the treatment of weakness, fever, and ‘severe’ diseases.96,120,121 Some people use IV drips to cool down during the summer (HQ, personal observation). These injections are given by physicians at clinics, by informal, untrained providers, by health workers who do home visits, and by pharmacists both trained and informal.122,123 The healthcare providers may even encourage the injection-seeking behavior because patients are more willing to pay an additional physician’s fee for injections but will not pay this added fee for oral medications.123 Syringes are reused and sterility of injections is often not maintained due to financial limitations and lack of risk awareness among the healthcare providers and the population in general.122 These injections appear to be the single most significant factor in the spread of HBV and HCV in the general population of Pakistan.

There are about 1.5 million units of blood products transfused each year in Pakistan.124 Data on the safety of this transfusion process are scanty – perhaps due to the lack of a system of reporting infectious or non-infectious adverse events.125 The transfusion network is poorly organized and likely contributes significantly in the transmission of serious infectious diseases. In fact, the leading hepatologist and public health scientist of Pakistan and editor of the country’s premier medical journal for 30 years died in 2004 of cerebral malaria that she acquired through a blood transfusion given during bilateral knee replacement surgery. Her case dramatized the need for regulation and control of the transfusion practices in Pakistan. Under the umbrella of National Blood Policy, comprehensive measures are needed in both public and private sectors of all four provinces. These measures should include a situational analysis and a realistic assessment of the blood requirement in the area, followed by recruitment and maintenance of voluntary, non-remunerated blood donors and standardization and regulation of appropriate blood screening procedures.

IDUs are numerous in Pakistani society and though they have a disproportionately high burden of health problems, they have been inadequately studied. Limited data suggest the likelihood that the prevalences of hepatitis and HIV are very high in this community. Urgent efforts need to be made to better study this population and to apply globally effective programs like needle exchange and condom distribution together with appropriate counseling and therapy for their drug addiction. Unless serious infections are controlled in IDUs, they will continue to be the source of HBV, HCV, and now HIV to the general population in Pakistan.

While universal immunization against HBV has still not been achieved, significant advances have been made. HBV vaccine has been included in the EPI (Expanded Program for Immunization) since 2002. All healthcare providers in the public sector are eligible for free HBV vaccination. Full coverage with HBV vaccination in the general population would be ideal, but at least healthcare workers and other high-risk professionals should be immunized universally.

The Herculean task of reeducating healthcare providers, informal sector providers, high-risk persons, and the general population is worthy of investment, particularly now that HIV has risen markedly among IDUs, resulting in a concentrated, rather than a nascent epidemic.106,107 Urgent comprehensive efforts at the structural, healthcare provider, and individual level are needed to control the spread of these blood-borne infections (Table 1).

Table 1.

Suggested interventions for reducing the transmission of blood-borne infections in Pakistan in addition to HBV vaccination

| Risk factor | Structural level interventions | Health provider level interventions | Individual level interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injections in healthcare settings |

|

Education regarding:

|

Counseling for:

|

| Injection drug use |

|

Training regarding:

|

|

| Receipt of blood and blood products |

|

Education regarding:

|

Family education regarding:

|

| Occupational risk to healthcare workers |

|

Education regarding:

|

Education regarding:

|

| Prevention of mother to child transmission |

|

Education regarding:

|

|

| Sexual transmission |

|

Education regarding:

|

|

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; STD, sexually transmitted disease; ABC, ‘Abstinence’ for youth, ‘Be faithful’ for sexually active, and ‘Condom availability and education’ specially for high-risk persons and venues.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the help of the personnel of Vanderbilt University Eskind Biomedical Library Services in retrieving many of the manuscripts.

Financial support: This study was supported in part by the AIDS International Training and Research Program, Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health (grant #5D43TW001035).

Footnotes

This work was presented in part at the St. Jude/PIDS Pediatric Microbial Research Conference, February 9–10, 2007, Memphis, Tennessee, USA

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Previsani N, Lavanchy D. WHO/CDS/CSR/LYO/2002.2:Hepatitis B. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. Hepatitis B. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hepatitis C. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [(accessed August 2008 [Au?3]]. World Health Organization fact sheets. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol. 2006;45:529–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The world factbook. Pakistan. [accessed August 2008];USA: Central Intelligence Agency. 2007 Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/pk.html [Au?4]

- 5.California state facts. [accessed August 2008];United States Geological Survey. 2006 Available at: http://www.usgs.gov.

- 6.Country profile: Pakistan. [accessed August 2008];Library of Congress Federal Research Division. 2005 Available at: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/profiles/Pakistan.pdf.

- 7.The Constitutional basis for the Federation of Pakistan. The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. 2007 Available at: http://www.nrb.gov.pk/constitutional_and_legal/constitution/part1.notes.html=1accessed [Au?5]

- 8.Agresti A, Coull B. Approximate is better than ‘exact’ for interval estimation of binomial proportions. Am Stat. 1998;52:119–26. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agboatwalla M, Isomura S, Miyake K, Yamashita T, Morishita T, Akram DS. Hepatitis A, B and C seroprevalence in Pakistan. Indian J Pediatr. 1994;61:545–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02751716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan HI. A study of seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C in mothers and children in Lahore. Pak Pediatr J. 1996;20:163–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbas KA, Tanwani AK. Prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigenaemia in healthy children. J Pak Med Assoc. 1997;47:93–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan MA, Ali AS, Ul Hassan Z, Mir F, Ul Haque S. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B in children. Pak Pediatr J. 1998;22:75–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qasmi SA, Aqeel S, Ahmed M, Alam SI, Ahmad A. Detection of hepatitis B viruses in normal individuals of Karachi. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2000;10:467–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jafri W, Jafri N, Yakoob J, Islam M, Tirmizi SF, Jafar T, et al. Hepatitis B and C: prevalence and risk factors associated with seropositivity among children in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quddus A, Luby SP, Jamal Z, Jafar T. Prevalence of hepatitis B among Afghan refugees living in Balochistan, Pakistan. Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10:242–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aziz S, Muzzafar R, Hafiz S, Abbas Z, Zafar MN, Naqvi SA, et al. Helicobacter pylori, hepatitis viruses A, C, E antibodies and HBsAg — prevalence and associated risk factors in pediatric communities of Karachi. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2007;17:195–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatti FA, Shaheen N, Uz Zaman Tariq W, Amin M, Saleem M. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in blood donors in Northern Pakistan. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 1996;46:91–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kakepoto GN, Bhally HS, Khaliq G, Kayani N, Burney IA, Siddiqui T, et al. Epidemiology of blood-borne viruses: a study of healthy blood donors in Southern Pakistan. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1996;27:703–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bukhari SM, Khatoon N, Iqbal A, Naeem S, Shafqat S, Lone A, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B antigenaemia in Mayo Hospital Lahore. Biomedica. 1999;15:88–91. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Majed A, Qayyum A. Presence of hepatitis B virus in healthy donors at blood unit of Punjab Institute of Cardiology Lahore. Pak J Med Res. 2000;39:111–2. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed F, Shah SH, Tariq M, Khan JA. Prevalence of hepatitis B carrier and HIV in healthy blood donors at Ayub Teaching Hospital. Pak J Med Res. 2000;39:91–2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdul MS, Aamir K, Mehmood K. Seroprevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV infections among college going first time voluntary blood donors. J Pak Med Assoc. 2000;50:269–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryas M, Hussain T, Bhatti FA, Ahmed F, Uz Zaman Tariq W, Khattak MF. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in blood donors in Northern Pakistan. J Rawalpindi Med Coll. 2001;5:56–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khattak MF, Salamat N, Bhatti FA, Qureshi TZ. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B, C and HIV in blood donors in northern Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52:398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mumtaz S, Ur Rehman M, Muzaffar M, Ul Hassan M, Iqbal W. Frequency of seropositive blood donors for hepatitis B, C and HIV viruses in railway hospital Rawalpindi. Pak J Med Res. 2002;41:51–3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman MU, Akhtar GN, Lodhi Y. Transfusion transmitted HIV and HBV infections in Punjab, Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2002;18:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmad J, Taj AS, Rahim A, Shah A, Rehman M. Frequency of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in healthy blood donors of NWFP: a single center experience. J Postgrad Med Inst. 2004;18:343–52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asif N, Khokar N, Ilahi F. Seroprevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV infection among voluntary non-renumerated and replacement donors in Northern Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2004;20:24–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahmood MA, Khawar S, Anjum AH, Ahmed SM, Rafiq S, Nazir I, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B, C and HIV infection in blood donors of Multan region. Ann King Edward Med Coll. 2004;10:459–61. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaidi A, Tariq WZ, Haider KA, Ali L, Sattar A, Faqeer F, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B, C and HIV in healthy blood donors in Northwest of Pakistan. Pak J Pathol. 2004;15:11–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akhtar S, Younus M, Adil S, Hassan F, Jafri SH. Epidemiologic study of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in male volunteer blood donors in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdul MS, Nanan D, Sabir S, Altaf A, Kadir M. Hepatitis B and C infection in first-time blood donors in Karachi — a possible subgroup for sentinel surveillance. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12:735–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aziz MS. Prevalence of anti hepatitis C antibodies and hepatitis B surface antigen in healthy blood donors in Baltistan. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2006;56:189–91. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ijaz AU, Shafiq F, Toosi NA, Malik MN, Qadeer R. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C in blood donors: analysis of 2-years data. Ann King Edward Med Coll. 2007;13:59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sultan F, Mehmood T, Mahmood MT. Infectious pathogens in volunteer and replacement blood donors in Pakistan: a ten-year experience. Int J Infect Dis. 2007;11:407–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaudhary IA, Samiullah, Khan SS, Masood R, Sardar MA, Mallhi AA. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C among the healthy blood donors at Fauji Foundation Hospital, Rawalpindi Pak. J Med Sci. 2007;23:64–7. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alam M, Naeem MA. Frequency of hepatitis B surface antigen and anti-hepatitis C antibodies in apparently healthy blood donors in Northern areas. Pakistan J Pathol. 2007;18:11–4. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luby SP, Qamruddin K, Shah AA, Omair A, Pahsa O, Khan AJ, et al. The relationship between therapeutic injections and high prevalence of hepatitis C infection in Hafizabad, Pakistan. Epidemiol Infect. 1997;119:349–56. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897007899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marri SM, Ahmed J. Prevalence of hepatitis B antigenaemia in general population of Quetta, Balochistan. Biomedica. 1997;13:51–2. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanwani A, Ahmad N. Prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen and anti-hepatitis C virus in laboratory based data at Islamabad. Pak J Surg. 2000;19–20:25–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khokhar N, Gill ML, Malik GJ. General seroprevalence of hepatitis C and hepatitis B virus infections in population. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2004;14:534–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waseem R, Kashif MA, Khan M, Qureshi AW. Seroprevalence of HBsAg and anti-HCV in Ghurki Teaching Hospital, Lahore. Ann King Edward Med Coll. 2005;11:232–4. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abbas Z, Shazi L, Jafri W. Prevalence of hepatitis B in individuals screened during a countrywide campaign in Pakistan. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006;16:497–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mirza IA, Mirza SH, Irfan S, Siddiqi R, Tariq WZ, Janjua AN. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C in young adults seeking recruitment in the armed forces. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2006;56:192–7. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherif TB, Tariq WZ. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C in healthy adult male recruits. Pakistan J Pathol. 2006;17:147–50. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alam M, Tariq WZ, Akram S, Qureshi TZ. Frequency of hepatitis B and C in central Punjab. Pakistan J Pathol. 2006;17:140–1. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mirza IA, Kazmi SM, Janjua AN. Frequency of hepatitis B surface antigen and anti-HCV in young adults — experience in southern Punjab. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2007;17:114–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abdulla EM, Abdulla FE. Seropositive HBsAg frequency in Karachi and interior Sindh, Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2007;23:157–60. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parker SP, Khan HI, Cubitt WD. Detection of antibodies to hepatitis C virus in dried blood spot samples from mothers and their offspring in Lahore, Pakistan. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2061–3. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.2061-2063.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aslam M, Aslam J. Seroprevalence of the antibody to hepatitis C in select groups in the Punjab region of Pakistan. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:407–11. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200111000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hyder SN, Hussain W, Aslam M, Maqbool S. Seroprevalence of anti-HCV in asymptomatic children. Pak J Pathol. 2001;12:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mujeeb SA, Shahab S, Hyder AA. Geographical display of health information: study of hepatitis C infection in Karachi, Pakistan. Public Health. 2000;114:413–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmad S, Gull J, Bano KA, Aftab M, Khokhar MS. Prevalence of anti-hepatitis C antibodies in healthy blood donors at Services Hospital Lahore. Pak Postgrad Med J. 2002;13:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rahman MU, Akhtar GN, Lodhi Y. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C antibodies in blood donors. Pak J Med Sci. 2002;18:193–6. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ali N, Nadeem M, Qamar A, Qureshi AH, Ejaz A. Frequency of hepatitis C virus antibodies in blood donors in Combined Military Hospital, Quetta. Pak J Med Sci. 2003;19:41–4. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akhtar S, Younus M, Adil S, Jafri SH, Hassan F. Hepatitis C virus infection in asymptomatic male volunteer blood donors in Karachi, Pakistan. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:527–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2004.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chaudry NT, Jameel W, Ihsan I, Nasreen S. Hepatitis C. Prof Med J. 2005;12:364–7. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahmad N, Asgher M, Shafique M, Qureshi JA. Evidence of high prevalence of hepatitis C virus in Faisalabad, Pakistan. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:390–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muhammad N, Jan MA. Frequency of hepatitis C in Buner, NWFP. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:11–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pasha O, Luby SP, Khan AJ, Shah SA, McCormick JB, Fisher-Hoch SP. Household members of hepatitis C virus-infected people in Hafizabad, Pakistan: infection by injections from health care providers. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;123:515–8. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899002770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Akhtar S, Moatter T, Azam SI, Rahbar MH, Adil S. Prevalence and risk factors for intrafamilial transmission of hepatitis C virus in Karachi, Pakistan. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:309–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2002.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Akhtar S, Moatter T. Intra-household clustering of hepatitis C virus infection in Karachi, Pakistan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2004;98:535–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Irfan A, Arfeen S. Hepatitis C virus infection in spouses. Pak J Med Res. 2004:43. [Au?6] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar N, Sattar R, Ara J. Frequency of hepatitis C virus in the spouses of HCV positive patients and risk factors of the two groups. J Surg Pak. 2004;9:36–9. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khokhar N, Gill ML, Alam AY. Interspousal transmission of hepatitis C virus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:587–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qureshi H, Arif A, Ahmed W, Alam SE. HCV exposure in spouses of the index cases. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:175–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anwar MS, Jaffery G, Rasheed SA. Serological screening of female prostitutes for anti-HIV and hepatitis B surface antigen. Pak J Health. 1998;35:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baqi S, Shah SA, Baig MA, Mujeeb SA, Memon A. Seroprevalence of HIV, HBV and syphilis and associated risk behaviours in male transvestites (Hijras) in Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56(1 Suppl 1):S17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bhatti FA, Amin M, Saleem M. Prevalence of antibody to hepatitis C virus in Pakistani thalassaemics by particle agglutination test utilizing C 200 and C 22-3 viral antigen coated particles. J Pak Med Assoc. 1995;45:269–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abdul MS, Shiekh MA, Khanani R, Jamal Q. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among beta-thalassaemia major patients. Trop Doct. 1997;27:105. doi: 10.1177/004947559702700220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hussain M, Khan MA, Mohammad J, Jan A. Frequency of hepatitis B and C in hemophiliac children. Pak Pediatr J. 2003;27:157–60. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mohammad J, Hussain M, Khan MA. Frequency of hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection in thalassemic children. Pak Pediatr J. 2003;27:161–4. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Younus M, Hassan K, Ikram N, Naseem L, Zaheer HA, Khan MF. Hepatitis C seropositivity in repeatedly transfused thalassemia major patients. Int J Pathol. 2004;2:20–3. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Burki MF, Hassan M, Hussain H, Nisar Y, Krishan J. Prevalence of anti-hepatitis C antibodies in multiply transfused beta thalassemia major patients. Ann Pak Inst Med Sci. 2005;1:150–3. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shah MA, Khan MT, Ulla Z, Ashfaq Y. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection in multi-transfused thalassemia major patients in North West Frontier Province. Pak J Med Sci. 2005;21:281–3. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abdul MS, Zuberi SJ, Lodi TZ, Mehmood K. Prevalence of HBV infection in health care personnel. J Pak Med Assoc. 1994;44:265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khan GM, Malik MN, Rana K, Fayyaz A. Profile of hepatitis B surface antigen positivity in health care personnel. Mother Child. 1996;34:135–8. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fazli Z, Asghar H, Baig NU, Fahmi A, Dil AS, Zaidi SS, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus in dental clinics in Rawalpindi/Islamabad. J Pak Med Assoc. 1998;48:259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mujeeb SA, Khatri Y, Khanani R. Frequency of parenteral exposure and seroprevalence of HBV, HCV, and HIV among operation room personnel. J Hosp Infect. 1998;38:133–7. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(98)90066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tariq WZ, Ghani E, Karamat KA. Hepatitis B in health care personnel. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2000;50:56–7. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aziz S, Memon A, Tily HI, Rasheed K, Jehangir K, Quraishy MS. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B and C amongst health workers of Civil Hospital Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52:92–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nadeem M, Yousaf MA, Mansoor S, Mansoor S, Khan FA, Zakaria M, et al. Seroprevalence of HBsAg and HCV antibodies in hospital workers compared to aged matched healthy blood donors. Pak J Pathol. 2004;15:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mujeeb SA, Shaikh MA, Kehar SI. Prevalence of HB infection in haemodialysis patients. J Pak Med Assoc. 1994;44:226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Khokhar N, Alam AY, Naz F. Hepatitis B surface antigenemia in patients on hemodialysis. Rawalpindi Med J. 2004;29:18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gul A, Iqbal F. Prevalence of hepatitis C in patients on maintenance haemodialysis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2003;13:15–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Khokhar N, Alam AY, Naz F, Mahmud SN. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection in patients on long-term hemodialysis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:326–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mehnaz A, Hashmi H, Syed S, Kulsoom Hepatitis B markers in mothers and its transmission in newborn. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2002;12:240–2. [Google Scholar]

- 88.GuleRana, Akmal N, Akhtar N. Prevalence of hepatitis B in pregnant females. Ann King Edward Med Coll. 2006;12:313. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yousfani S, Mumtaz F, Memon A, Memon MA, Sikandar R. Antenatal screening for hepatitis B and C virus carrier state at a University Hospital. J Liaqat Univ Med Health Sci. 2006;5:24–7. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zafar MA, Mohsin A, Husain I, Shah AA. Prevalence of hepatitis C among pregnant women. J Surg Pak. 2001;6:32–3. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rizvi TJ, Fatima H. Frequency of hepatitis C in obstetric cases. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2003;13:688–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Khokhar N, Raja KS, Javaid S. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and its risk factors in pregnant women. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jaffery T, Tariq N, Ayub R, Alam AY. Frequency of hepatitis C in pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:716–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Simonsen L, Kane A, Lloyd J, Zaffran M, Kane M. Unsafe injections in the developing world and transmission of bloodborne pathogens: a review. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:789–800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hauri AM, Armstrong GL, Hutin YJ. The global burden of disease attributable to contaminated injections given in health care settings. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15:7–16. doi: 10.1258/095646204322637182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Khan AJ, Luby SP, Fikree F, Karim A, Obaid S, Dellawala S, et al. Unsafe injections and the transmission of hepatitis B and C in a periurban community in Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:956–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Usman HR, Akhtar S, Rahbar MH, Hamid S, Moattar T, Luby SP. Injections in health care settings: a risk factor for acute hepatitis B virus infection in Karachi, Pakistan. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;130:293–300. doi: 10.1017/s0950268802008178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bari A, Akhtar S, Rahbar MH, Luby SP. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection in male adults in Rawalpindi-Islamabad, Pakistan. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:732–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shazi L, Abbas Z. Comparison of risk factors for hepatitis B and C in patients visiting a gastroenterology clinic. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006;16:104–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Luby S, Hoodbhoy F, Jan A, Shah A, Hutin Y. Long-term improvement in unsafe injection practices following community intervention. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:52–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Luby S, Khanani R, Zia M, Vellani Z, Ali M, Qureshi AH, et al. Evaluation of blood bank practices in Karachi, Pakistan, and the government’s response. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56(1 Suppl 1):S25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ahmed M. Hepatitis B surface antigen study in professional and volunteer blood donors. Ann Abbasi Shaheed Hospital Karachi. Med Dental Coll. 2001;6:304–6. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Drug abuse in Pakistan — results from year 2000 national assessment. Pakistan: United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention and The Narcotics Control Division, Anti-Narcotics Force, Government of Pakistan; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kuo I, Ul-Hasan S, Galai N, Thomas DL, Zafar T, Ahmed MA, et al. High HCV seroprevalence and HIV drug use risk behaviors among injection drug users in Pakistan. Harm Reduct J. 2006;3:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Achakzai M, Kassi M, Kasi PM. Seroprevalences and co-infections of HIV, hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus in injecting drug users in Quetta, Pakistan. Trop Doct. 2007;37:43–5. doi: 10.1258/004947507779951989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pilot survey of vulnerable populations of IDUs, FSWs, MSWs, and Hijras in Karachi. Pakistan: The Consultant Group, Infection Control Society P, Pakistan AIDS Prevention Society, Interactive Research and Development; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 107.National study of reproductive tract and sexually transmitted infections — survey of high risk groups in Lahore and Karachi. Pakistan: National AIDS Control Program, Ministry of Health, Government of Pakistan/Family Health International/Department for International Development; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Immunization profile — Pakistan. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [accessed August 2008]. Available at: http://www.who.int/vaccines/globalsummary/immunization/countryprofileresult.cfm?C='pak'. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Janjua NZ, Nizamy MA. Knowledge and practices of barbers about hepatitis B and C transmission in Rawalpindi and Islamabad. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:116–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vandelli C, Renzo F, Romano L, Tisminetzky S, De Palma M, Stroffolini T, et al. Lack of evidence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C among monogamous couples: results of a 10-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:855–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Alary M, Joly JR, Vincelette J, Lavoie R, Turmel B, Remis RS. Lack of evidence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus in a prospective cohort study of men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:502–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.020388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lobato C, Tavares-Neto J, Rios-Leite M, Trepo C, Vitvitski L, Parvaz P, et al. Intrafamilial prevalence of hepatitis B virus in Western Brazilian Amazon region: epidemiologic and biomolecular study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:863–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Abdool Karim SS, Thejpal R, Coovadia HM. Household clustering and intra-household transmission patterns of hepatitis B virus infection in South Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:495–503. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.2.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zervou EK, Gatselis NK, Xanthi E, Ziciadis K, Georgiadou SP, Dalekos GN. Intrafamilial spread of hepatitis B virus infection in Greece. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:911–5. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200509000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Transmission of hepatitis B and C viruses in outpatient settings — New York, Oklahoma, and Nebraska, 2000–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:901–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Transmission of hepatitis B virus among persons undergoing blood glucose monitoring in long-term-care facilities — Mississippi, North Carolina, and Los Angeles County, California, 2003–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:220–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Transmission of hepatitis B virus in correctional facilities — Georgia, January 1999–June 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:678–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hutin YJ, Hauri AM, Armstrong GL. Use of injections in healthcare settings worldwide, 2000: literature review and regional estimates. BMJ. 2003;327:1075. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7423.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Janjua NZ, Hutin YJ, Akhtar S, Ahmad K. Population beliefs about the efficacy of injections in Pakistan’s Sindh province. Public Health. 2006;120:824–33. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Altaf A, Fatmi Z, Ajmal A, Hussain T, Qahir H, Agboatwalla M. Determinants of therapeutic injection overuse among communities in Sindh, Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2004;16:35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Raglow GJ, Luby SP, Nabi N. Therapeutic injections in Pakistan: from the patients’ perspective. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:69–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Janjua NZ. Injection practices and sharp waste disposal by general practitioners of Murree, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2003;53:107–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Janjua NZ, Akhtar S, Hutin YJ. Injection use in two districts of Pakistan: implications for disease prevention. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:401–8. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kazi BM. Standards and guidelines for blood transfusion services. Islamabad, Pakistan: World Health Organization/National Institute of Health, Federal Health Ministry, Government of Pakistan; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rahman M, Jawaid SA. Need for national blood policy to ensure safe blood transfusion. Pak J Med Sci. 2004;20:81–4. [Google Scholar]