Abstract

Purpose

Adjuvant chemotherapy for early stage non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is now the standard of care, but there is little information regarding its impact on quality of life (QOL). We report the QOL results of JBR.10, a North American, intergroup, randomized trial of adjuvant cisplatin and vinorelbine compared with observation in patients who have completely resected, stages IB to II NSCLC.

Patients and Methods

QOL was assessed with the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 and a trial-specific checklist at baseline and at weeks 5 and 9 for those who received chemotherapy and at follow-up months 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36. A 10-point change in QOL scores from baseline was considered clinically significant.

Results

Four hundred eighty-two patients were randomly assigned on JBR.10. A total of 173 patients (82% of the expected) in the observation arm and 186 (85% of expected) in the chemotherapy arm completed baseline QOL assessments. The two groups were comparable, with low global QOL scores and significant symptom burden, especially pain and fatigue, after thoracotomy. Changes in QOL during chemotherapy were relatively modest; fatigue, nausea, and vomiting worsened, but there was a reduction in pain and no change in global QOL. Patients in the observation arm showed considerable improvements in QOL by 3 months. QOL, except for symptoms of sensory neuropathy and hearing loss, in those treated with chemotherapy returned to baseline by 9 months.

Conclusion

The findings of this trial indicate that the negative effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on QOL appear to be temporary, and that improvements (with a return to baseline function) are likely in most patients.

INTRODUCTION

Non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the leading cause of cancer mortality.1,2 Adjuvant therapy for early-stage NSCLC has been the focus of much study in the hope of reducing relapse risk and improving survival from the 40% to 60% achieved with surgery alone.2 Initial studies produced mixed results.3 In 1994, the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCIC CTG) initiated a trial of adjuvant chemotherapy in completely resected, early-stage NSCLC (JBR.10), which revealed that overall survival was substantially improved with chemotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.69; 15% absolute improvement in 5-year survival, 54% to 69%).4 Other recent trials5,6 and a pooled analysis7 have confirmed this observation. However, given the potential toxicity of chemotherapy, the impact of treatment on patients’ quality of life (QOL) is an important consideration.8-10 This report details the results of QOL assessments in patients enrolled on JBR.10.

Our study hypothesis was that QOL would be impaired for patients who received chemotherapy during and just after completion of treatment and that it might remain impaired in the follow-up period.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Trial Design and Patient Population

JBR.10 was a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial that evaluated the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on overall survival in patients who had completely resected NSCLC. Secondary end points included relapse-free survival, toxicity, and QOL.

The study was led by the NCIC CTG and had participation from Cancer and Leukemia Group B, Southwest Oncology Group, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), and it was supported by the Canadian Cancer Society, National Cancer Institute, and GlaxoSmithKline. All data collection and data analyses were done by the NCIC CTG. Eligibility criteria included the following: completely resected T2N0, T1N1, or T2N1 NSCLC; and ECOG performance status of 0 or 1. A total of 532 patients were registered, and 482 of these were randomly assigned to observation (n = 240) or chemotherapy (n = 242). Chemotherapy was started within 6 weeks of surgery and consisted of four cycles of cisplatin and vinorelbine. The study was approved by research ethics boards at the participating institutions; all patients provided written consent. Details of the survival and of chemotherapy compliance have been reported previously.4,11

QOL Assessment

QOL was assessed with the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30), a well-validated and widely used QOL tool12,13and with a trial-specific symptom checklist; the lung cancer questionnaire module, QLQ-LC13, was not available at the time of study design.

QLQ-C30 has thirty questions that relate to global health status, five functional domains (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, social), three symptom domains (pain, fatigue, nausea/vomiting), and six single items (dyspnea, insomnia, anorexia, diarrhea, constipation, financial difficulties). The trial-specific symptom checklist consisted of 15 single items that were chosen from the NCIC CTG item bank as relevant to the study question but not addressed by the core questionnaire. Those items (cough, coughing up phlegm, coughing blood, shortness of breath [SOB] while resting, SOB while walking, numbness of fingers or toes, feeling pins and needles in fingers or toes, hair loss, fever, sweating, bruising, a loss of hearing, taking pain medications, pain remaining after medications, and worry about future health) were answered by using the same four-category response as the core questionnaire and were reported as single items. Raw scores for each domain and symptom were transformed to a 0-to-100 scale. A higher score for functional domains indicated better QOL, whereas a lower score for symptom domains and single items indicated fewer symptoms.

Collection of QOL Data

Patients were to complete a baseline QOL assessment within 14 days before random assignment; again at weeks 5 and 9 in the chemotherapy arm; at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months post–random assignment in both study arms; and, subsequently, at the time of scheduled clinic appointments every 6 months.14

Statistical Analysis

Compliance with QOL data collection was expressed as the percentage of eligible patients expected to complete QOL questionnaires (ie, those who had done so at baseline, had received assigned treatment, and had not suffered a relapse) at a certain time point. Patients were censored in the event of disease relapse or death from any cause. QOL response (ie, the proportion of patients who improved or worsened) was calculated separately for the initial time period (up to 6 months) and for the follow-up period (9 months and beyond) for the two study arms.

A change in score of 10 points from baseline was defined as clinically significant on the basis of previous studies15,16 and published NCIC CTG guidelines.17 For functional domain scores, patients were classified as improved if there was a score at least 10 points greater than baseline at any time point in the assessment period. Conversely, patients were considered worsened if there was a drop in the score to at least 10 points less than baseline at any time point in the QOL assessment without observation of the above-defined improvement. Patients whose scores were between 10-point changes from baseline at every QOL assessment were considered stable. For symptom domains and single items, the classification of responses was reversed, as lower scores from baseline indicate improvement. No primary time point was stipulated for the QOL analysis; both early and late changes were of clinical interest.

The χ2 test was performed to compare the distributions of data in these three categories between the two study arms. The Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test for trend was used to test whether one treatment arm had higher proportions in the better-QOL categories than the other arm. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare changes in QOL score at each assessment time from baseline between treatment arms. The Kaplan-Meier product-limit method was used to summarize the overall survival distributions, whereas the Cox regression model was used to study the prognostic and predictive effects of the baseline QOL score (< median v ≥ median) on overall survival.

To explore more complex analysis that accounted in part for missing data, mixed linear models with treatment, time, and treatment-by-time interactions as fixed effects were fit to the longitudinal QOL data of each item by using data from all patients who had baseline scores and at least one follow-up measure. The goodness of fit for the resulting model was checked by Akaike information criterion.18 Maximum likelihood estimates of fitted model parameters and P values for testing the initial treatment effect and the treatment effect with time were calculated.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Primary Outcome

Four hundred eighty-two patients were randomly assigned onto JBR.10. There were no significant imbalances in patient characteristics between the two study arms: the median age was 61 years, 65% were male, 55% had stage II NSCLC, 24% were treated with pneumonectomy, and 51% had an ECOG performance status of 1.

Patients in the chemotherapy arm had a 5-year relapse-free survival rate of 61% (95% CI, 54% to 61%) compared with 48% (95% CI, 42% to 55%) in the observation arm (P = .002). Median survival was 94 months for the chemotherapy group compared with 73 months for patients in the observation arm (HR 0.70; P = .012).

Compliance to QOL Assessment

All cooperative groups except Cancer and Leukemia Group B (50 patients accrued) participated in the QOL assessment, although completion of QOL was only mandatory for NCIC CTG patients. The compliance with QOL assessment is summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1. In the chemotherapy arm, 186 patients completed the baseline QOL assessment, which represented 77% of all patients and 85% of patients from groups that participated in the QOL assessment. Similar compliance (173 patients; 72% of all, 82% of expected) was seen in the observation arm. Compliance in completion of the QOL questionnaire at follow-up visits (of patients who submitted baseline QOL data and did not suffer a relapse) was in the range of 60% to 80% for most time points, and there were no significant differences between the study arms. Despite attempts to collect the reason for missing QOL information, these data were not supplied for the majority of missing forms.

Fig 1.

Flow chart of compliance with quality-of-life (QOL) questionnaire completion.

Table 1.

Compliance with Quality-of-Life Questionnaire Completion

| Study Arm | Total No. of Patients | Questionnaire Time Point

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Expected

|

Postbaseline

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Week 5

|

Week 9

|

Week 12

|

Weeks 20/24 (6 months)

|

9 Months

|

12 Months

|

18 Months

|

24 Months

|

30 Months

|

36 Months

|

||||||||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Chemotherapy | 242 | 186 | 85* | 103 | 77 | 95 | 84 | 71 | 76 | 77 | 75 | 94 | 71 | 82 | 71 | 85 | 66 | 76 | 62 | 59 | 55 | 50 | 53 |

| Observed | 240 | 173 | 82† | — | — | — | — | 127 | 79 | 85 | 61 | 96 | 81 | 88 | 81 | 73 | 71 | 62 | 67 | 52 | 63 | 39 | 56 |

NOTE. Number received as a percentage of the number expected at a given time point.

85% reflects the 186 patients who completed a quality-of-life questionnaire of the 220 patients in the chemotherapy arm who were expected to complete the questionnaire.

82% reflects the 173 patients who completed a quality-of-life questionnaire of the 212 patients in the observation arm who were expected to complete the questionnaire.

Patients were more likely to have contributed QOL data if they were male (78% of men completed baseline QOL questionnaires v 68% of women; P = .03), if they had an ECOG performance status of 1 (79% v 70% of patients with an ECOG status of 0; P = .024), and if they had stage IB disease (83% v 68% of patients with stage II disease; P < .001). However, the overall survival of the subset of patients with baseline QOL data was not different from the trial population as a whole. In the observation arm, patients who provided QOL data at 9 months had better subsequent survival than patients who did not provide QOL data at 9 months (P = .01); no such survival difference between patients who provided and who did not provide QOL data occurred in the chemotherapy arm (P = .24).

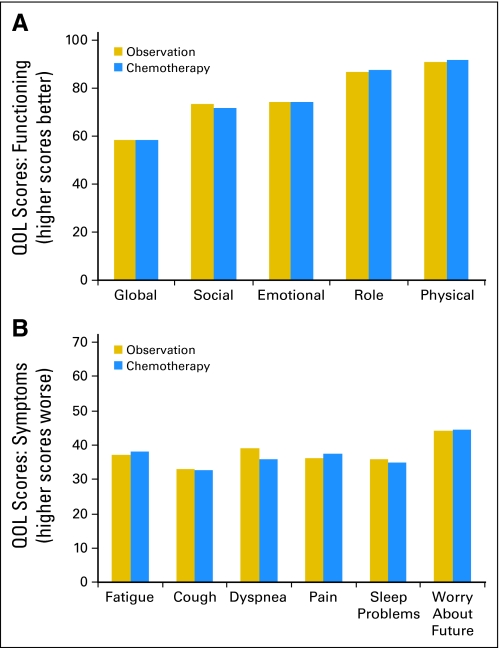

Baseline QOL Results

The two study arms had similar baseline QOL scores in all domains and items (Fig 2). The greatest impairment (ie, lowest baseline scores) was seen in the global QOL score (mean score, 57.6; standard deviation [SD], 20.3), followed by impairments in social (mean, 72.1; SD 25.8) and emotional functioning (mean, 73.6; SD, 22.9). There were relatively high levels of physical (mean, 90.8; SD, 7.5) and role functioning (mean, 87.0; SD, 12.5). Symptom domains and single items that indicated greater impairment were fatigue (mean, 37.7; SD, 20.6), dyspnea (mean, 37.4; SD, 22.5), pain (mean, 36.8; SD, 23.7), sleep problems (mean, 35.4; SD, 28.7), and cough (mean, 33.0; SD, 22.0). Another item that had high baseline scores (which indicated a greater degree of concern) was worry about the future, which had a mean score of 45.4 (SD, 30.2). Patients who underwent pneumonectomy had worse mean baseline scores for global QOL (53.6 p v 58.9; P = .039), role function (84.1 v 87.9; P = .014) and dyspnea (43.0 p v 35.7; P = .007) compared with patients who underwent lobectomy.

Fig 2.

Baseline quality-of-life (QOL) scores in the two arms.

QOL in the Early Postsurgery Period (baseline to 3 months)

Analysis of the proportion of patients who had QOL scores that improved, remained stable, or became worse compared with baseline revealed that a higher proportion of patients in the observation arm reported improved QOL in the global (P < .001), physical (P < .001), role (P < .001), cognitive (P = .04), and social functioning (P = .01) domains compared with patients in the chemotherapy arm. Significantly more patients who were treated with chemotherapy experienced worsened fatigue (P < .001), appetite (P < .001), hair loss (P < .001), nausea (P < .03) and vomiting (P = .01). These proportions are illustrated in the first bar of Figure 3, which depicts the 12-week data.

Fig 3.

Proportion of patients with improved, stable, and worsened quality of life, and proportion of patients with missing quality-of-life data, in several domains and symptoms at 12 weeks and 12 months of follow-up.

QOL in Later Follow-Up (9 months and beyond)

At the 9-month time point, the global QOL of the patients in the chemotherapy arm was comparable with that of patients in the observation arm, which indicated a recovery of QOL scores for patients treated with chemotherapy. This is illustrated in Figure 3 for the 12-month time point and in Figure 4, which documents the mean baseline scores and mean change scores by study arm, and the possible bias caused by reduced compliance to QOL questionnaire completion in follow-up visits. There were no statistically significant differences in the global and five functional domains of QOL between the two treatment arms. Patients in the chemotherapy arm had better scores in symptom items of nausea (P = .001) and fever (P = .1), but worse scores for numbness (P < .001), pins and needles (P = .02), and loss of hearing (P = .03). Numbness of the fingers/toes and pins/needles sensation persisted, with detectable clinically significant differences (change scores of 10 to 20 points) up to 30 months.

Fig 4.

Mean quality-of-life baseline scores and mean change scores by study arm in follow-up period.

Mixed Linear Modeling Results

Results of the mixed linear modeling provided information similar to that provided in the primary analyses above; that is, that patients who received chemotherapy had worse QOL in the global and functional domains during the treatment period but subsequently improved after treatment completion. Summary of the analysis of the global QOL and physical, role, emotional, social, and cognitive functioning and the clinical interpretation are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results from Linear Mixed Model

| Factor and Treatment Arm by Domain | Model Parameter Estimate |

P

|

Clinical Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within-Arm Comparison | Between-Arm Comparison | |||

| Global quality of life | ||||

| Change from baseline to 3 months | ||||

| Observation | 12.2 | < .0001 | < .001 | At 3 months, patients in observation arm improved by 12 points, whereas patients in chemotherapy arm deteriorated by 7 points, on average; both were significant changes from baseline, and difference between arms was significant |

| Chemotherapy | −6.9 | .015 | ||

| Subsequent change rate per month | ||||

| Observation | −0.1 | .14 | < .001 | After 3 months, there was no significant change in global quality-of-life scores for patients in observation arm, but scores for patients in chemotherapy arm significantly improved; difference in rate of change between arms was significant |

| Chemotherapy | 0.35 | .001 | ||

| Physical functioning | ||||

| Change from baseline to 3 months | ||||

| Observation | 4.2 | < .0001 | < .0001 | A small improvement in physical functioning at 3 months for patients randomly assigned to observation arm and a small deterioration for patients in chemotherapy arm; both changes are clinically small but statistically significant |

| Chemotherapy | −3.1 | .002 | ||

| Subsequent change rate per month | ||||

| Observation | −0.02 | .298 | .076 | No significant change for observation arm; gradual improvement in physical functioning for patients randomly assigned to chemotherapy arm; difference in rate of change between arms was not significant |

| Chemotherapy | 0.07 | .014 | ||

| Role functioning | ||||

| Change from baseline to 3 months | ||||

| Observation | 6.7 | < .0001 | < .001 | An improvement at 3 months in role functioning for patients randomly assigned to observation arm and a small deterioration for patients in chemotherapy arm; both were significant changes from baseline, and the difference between arms was significant |

| Chemotherapy | −3.8 | .017 | ||

| Subsequent change rate per month | ||||

| Observation | 0.03 | .357 | .15 | No significant change for observation arm; gradual improvement in role functioning for patients randomly assigned to chemotherapy arm; difference in the rate of change between arms was not significant |

| Chemotherapy | 0.11 | .017 | ||

| Emotional functioning | ||||

| Change from baseline to 3 months | ||||

| Observation | 6.1 | .0015 | .04 | Statistically significant improvement in emotional functioning at 3 months for patients randomly assigned to observation, and little change for patients in chemotherapy arm; difference between arms was significant |

| Chemotherapy | −0.68 | .81 | ||

| Subsequent change rate per month | ||||

| Observation | −0.03 | .53 | .1 | No significant change in emotional functioning after the 3-month time point |

| Chemotherapy | 0.12 | .12 | ||

| Social functioning | ||||

| Change from baseline to 3 months | ||||

| Observation | 13.78 | < .0001 | < .0001 | At 3 months, social functioning of patients in observation arm improved by 13 points, whereas patients in chemotherapy arm deteriorated 6 points, on average; difference between arms was highly significant |

| Chemotherapy | −6.3 | .071 | ||

| Subsequent change rate per month | ||||

| Observation | −0.04 | .552 | .01 | No significant change for observation arm; gradual improvement in social functioning for patients randomly assigned to chemotherapy; difference in rate of change between arms was significant |

| Chemotherapy | 0.26 | .009 | ||

| Cognitive functioning | ||||

| Change from baseline to 3 months | ||||

| Observation | 2.16 | .17 | .02 | Small improvement in cognitive functioning in the observation arm and small deterioration in the chemotherapy arm at 3 months; difference between the arms is statistically significant |

| Chemotherapy | −4.52 | .05 | ||

| Subsequent change rate per month | ||||

| Observation | −0.08 | .07 | .06 | Minimal changes with time, of borderline significance |

| Chemotherapy | 0.07 | .29 | ||

Relationship of QOL and Other Outcomes

Patients with better baseline global QOL, physical, and role functioning scores (ie, scores greater than the median) had significantly longer survival (P = .015, .005, and < .001, respectively), but they showed a reduced treatment effect (P = .008, .02, and .04, respectively; Appendix Fig A1, online only). Patients with higher symptom scores for fatigue, pain, and SOB on walking had reduced survival compared with baseline patients who had fewer of those symptoms (data not shown).

Baseline QOL scores had no impact on compliance with treatment (ie, they did not predict for patients who completed all of the intended chemotherapy; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The ultimate aim of adjuvant systemic therapy is to improve overall survival for early-stage malignancies after definitive local management. In achieving this end, some risk of adverse effects becomes accepted, particularly with respect to the acute toxicity of chemotherapy.

Although adjuvant chemotherapy is considered standard after surgery for breast and colon cancers, it is only recently that the results of trials such as JBR.10 have prompted re-evaluation of treatment guidelines for resected NSCLC.19,20 The adoption rate for this new therapy for patients who have completely resected NSCLC will be influenced by oncologists’ views of prior negative trials and by their perceptions of both the positive and negative impacts of chemotherapy on this particular patient population.21-23

NSCLC occurs in an older patient population and in individuals who may have other comorbid conditions related to tobacco use.24,25 The immediate impact of thoracotomy on physical function is significant, even in those patients without other health concerns, although the effect may be temporary.26,27 The delivery of adjuvant chemotherapy after lobectomy, and especially after pneumonectomy, is anticipated to be a challenge,11 and there may be reluctance on the part of patients to accept treatment despite potential long-term survival benefits. This is certainly the case when aggressive treatment is considered in patients who have locally advanced NSCLC.28

A description of the effect of chemotherapy on QOL is critical to informing patients and oncologists about the outcomes of adjuvant systemic therapy.29 To our knowledge, this is the first, and to date the only, analysis of QOL from a prospective, randomized, controlled trial of adjuvant chemotherapy in NSCLC. Our data show that overall QOL and functional domain scores are somewhat compromised after thoracotomy, particularly after pneumonectomy; this is presumably an effect of surgery (as recently detailed by Kenny et al30), but scores improve fairly quickly in patients who are not receiving chemotherapy. As expected, adjuvant chemotherapy has an immediate negative impact on a number of aspects of QOL in individuals with NSCLC who have undergone resection with curative intent. Chief among these are the symptoms that reflect most of the major adverse effects associated with platinum-based chemotherapy: fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, and vomiting.31,32

Functional impairment is not unusual for individuals who are taking chemotherapy, and this is reflected in the differences between those treated and observed in terms of global QOL and four of the five functional scales of the QLQ-C30. However, by 9 months, when most of the acute adverse effects of chemotherapy have resolved, there is a return to normal function. The only persistent symptom scale score differences, specifically peripheral neuropathy and ototoxicity, are due to the late effects of cisplatin. This also has been reported in long-term survivors of testicular cancer who were treated with cisplatin.33 Of note, fatigue did not appear to be a persistent issue for patients postchemotherapy. Given that global QOL scores improve and are comparable with those of patients who have not experienced chemotherapy, the significance of these complaints on the overall status of the individual is presumably modest, although strategies to address these problems would still be worthwhile. With regard to patients’ worries about future health, symptom scores were high at baseline but improved in both patient groups, which indicated that patients who were receiving chemotherapy did not appear to be more reassured than those who received no further treatment.

Not surprisingly, patients with better QOL scores and fewer symptoms had better survival. However, better scores were not associated with a greater likelihood of benefit from chemotherapy. On the contrary, patients with better scores had a reduced treatment effect, although this finding was not a result of a predefined hypothesis and may have been a chance finding. Nevertheless, this observation, coupled with analyses that demonstrate that older patients are just as likely to have a survival advantage from chemotherapy,34 suggests that these patient variables may not predict who will or will not benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.

The relatively low completion rates of QOL assessments in long-term follow-up on this trial limit the generalizability of the findings, but it is notable that compliance was comparable between the two arms of the study. Missing assessments appear not to have been a function of chemotherapy treatment but more likely were a general characteristic of the patient population. However, it is quite possible that fitter patients, and those with better QOL scores, were more compliant with continued QOL assessment. It also should be noted that that only 48% to 50% of patients completed all four cycles of chemotherapy;11 thus, the QOL results may not capture the impact of a complete course of adjuvant chemotherapy. Although the secondary analysis that used a linear mixed model to explore the effects of assigned treatment arm and time on QOL scores confirmed that patients improve significantly once chemotherapy is completed, this type of analysis does not adequately address the fact that QOL data was likely missing not at random. More complex statistical analyses, such as a joint modeling approach, could be explored, but models would, of necessity, make assumptions that would be difficult or impossible to verify, and that would limit clinical interpretation. Instead, we have displayed the missing data at each relevant time point in the figures alongside the data that represent best response in terms of change in QOL from baseline.

Another potential limitation of the analysis is the possibility of a response shift. The surgical intervention35,36,37 and the expectations that chemotherapy might reduce relapse risk might influence patients’ perceptions of the QOL effects of treatment.

The magnitude of the survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy seen in JBR.10 and other recent trials is comparable with that seen with adjuvant systemic therapy for resected colon38 and breast cancer.39,40 The number of patients with resected NSCLC who receive adjuvant chemotherapy will increase as the treatment becomes incorporated into routine clinical practice. The findings of this trial indicate, on the basis of the available data (bearing in mind possible bias given missing data from a considerable proportion of patients), that the negative effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on QOL appear temporary and that improvements, with a return to baseline function, are likely in most patients.

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: David H. Johnson, Merck & Co (C), Johnson & Johnson (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: Frances A. Shepherd, Pierre Fabre Research Funding: Christopher W. Lee, GlaxoSmithKline; Lesley Seymour, GlaxoSmithKline Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Andrea Bezjak, Keyue Ding, Timothy Winton, David H. Johnson, Frances A. Shepherd

Administrative support: Barbara Graham

Provision of study materials or patients: Timothy Winton, David H. Johnson, Robert B. Livingston, Frances A. Shepherd

Collection and assembly of data: Barbara Graham, Lesley Seymour

Data analysis and interpretation: Andrea Bezjak, Christopher W. Lee, Keyue Ding, Michael Brundage, Marlo Whitehead, Lesley Seymour, Frances A. Shepherd

Manuscript writing: Andrea Bezjak, Christopher W. Lee, Keyue Ding, Timothy Winton, Michael Brundage, Barbara Graham, Marlo Whitehead, David H. Johnson, Robert B. Livingston, Lesley Seymour, Frances A. Shepherd

Final approval of manuscript: Andrea Bezjak, Christopher W. Lee, Keyue Ding, Timothy Winton, Michael Brundage, Barbara Graham, Marlo Whitehead, David H. Johnson, Robert B. Livingston, Lesley Seymour, Frances A. Shepherd

Appendix

Fig A1.

Global quality-of-life scores (> and < median) and overall survival (OS) by treatment arm.

Fig A2.

Global quality-of-life scores (> and < median) and overall survival (OS) by treatment arm.

published online ahead of print at www.jco.org on September 22, 2008

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT00002583

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, et al: Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin 55:10-30, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mountain C: Revisions in the International System for Staging Lung Cancer. Chest 111:1710-1717, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group: Chemotherapy in non–small-cell lung cancer—A meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. BMJ 311:899-909, 1995 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winton T, Livingston R, Johnson D, et al: Vinorelbine plus cisplatin vs. observation in resected non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 352:2589-2597, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arriagada R, Bergman B, Dunant A, et al: Cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 350:351-360, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douillard J, Rosell R, De Lena M, et al: Adjuvant vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus observation in patients with completely resected stage IB-IIIA non–small-cell lung cancer (Adjuvant Navelbine International Trialist Association [ANITA]): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 7:719-727, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alam N, Darling G, Evans WK, et al: Adjuvant chemotherapy for completely resected non–small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 58:146-155, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cullen M: Adjuvant and neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in non–small-cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 6:43-47, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wada H: Adjuvant treatment of early stage non–small-cell lung cancer. Oncology 13:102-105, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford J: The importance of chemotherapy dose intensity in lung cancer. Semin Oncol 31:25-31, 2004. (suppl 15) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alam N, Shepherd F, Winton T, et al: Compliance with post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: An analysis of National Cancer Institute of Canada and intergroup trial JBR.10 and a review of the literature. Lung Cancer 47:385-394, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earle C: Outcomes research in lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr:56-77, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Aaronson N, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al: The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:365-376, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osoba D: The Quality of Life Committee of the Clinical Trials Group of the National Cancer Institute of Canada: Organization and functions. Qual Life Res 1:211-218, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King M: The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res 5:555-567, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al: Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16:139-144, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osoba D, Bezjak A, Brundage M, et al: Analysis and interpretation of health-related quality-of-life data from clinical trials: Basic approach of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Eur J Cancer 41:280-287, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akaike H: A new look at the statistical model identification: IEEE Trans Automat Contr 19:716-723, 1974 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blum R: Adjuvant chemotherapy for lung cancer: A new standard of care. N Engl J Med 350:404-405, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pisters K: Adjuvant chemotherapy for non–small-cell lung cancer: The smoke clears. N Engl J Med 352:2640-2642, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynch T, Bogart J, Curran WJ, et al: Early-stage lung cancer: New approaches to evaluation and treatment—Conference summary statement. Clin Cancer Res 11:4981s-4983s, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scagliotti G: The ALPI Trial: The Italian/European experience with adjuvant chemotherapy in resectable non–small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 11:5011s-5016s, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunant A, Pignon J, Le Chevalier T: Adjuvant chemotherapy for non–small-cell lung cancer: Contribution of the International Adjuvant Lung Trial. Clin Cancer Res 11:5017s-5021s, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tammemagi C, Neslund-Dudas C, Simoff M, et al: Impact of comorbidity on lung cancer survival. Int J Cancer 103:792-802, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janssen-Heijnen M, Smulders S, Lemmens V, et al: Effect of comorbidity on the treatment and prognosis of elderly patients with non–small-cell lung cancer. Thorax 59:602-607, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dales R, Belanger R, Shamji F, et al: Quality-of-life following thoracotomy for lung cancer. J Clin Epidemiol 47:1443-1449, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li W, Lee T, Lam S, et al: Quality of life following lung cancer resection: Video-assisted thoracic surgery vs thoracotomy. Chest 122:584-589, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brundage M, Davidson J, Mackillop W: Trading treatment toxicity for survival in locally advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 15:330-340, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brundage M, Feldman-Stewart D, Leis A, et al: Communicating quality of life information to cancer patients: A study of six presentation formats. J Clin Oncol 23:6949-6956, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenny PM, King MT, Viney RC, et al: Quality of life and survival in the 2 years after surgery for non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 26:233-241, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gridelli C, Gallo C, Shepherd F, et al: Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine compared with cisplatin plus vinorelbine or cisplatin plus gemcitabine for advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: A phase III trial of the Italian GEMVIN Investigators and the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 21:3025-3034, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Maio M, Perrone F, Gallo C, et al: Supportive care in patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 89:1013-1021, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bokemeyer C, Berger C, Kuczyk M, et al: Evaluation of long-term toxicity after chemotherapy for testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol 14:2923-2932, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pepe C, Hasan B, Winton T, et al: Adjuvant vinorelbine and cisplatin in elderly patients: National Cancer Institute of Canada and Intergroup Study JBR.10. J Clin Oncol 25:1553-1561, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernhard J, Lowy A, Maibach R, et al: Response shift in the perception of health for utility evaluation: An explorative investigation. Eur J Cancer 37:1729-1735, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Handy JJ, Asaph J, Skokan L, et al: What happens to patients undergoing lung cancer surgery? Outcomes and quality of life before and after surgery. Chest 122:21-30, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Win T, Sharples L, Wells F, et al: Effect of lung cancer surgery on quality of life. Thorax 60:234-238, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engstrom P, Benson Ar, Chen Y, et al: Colon cancer clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 3:468-491, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bria E, Nistico C, Cuppone F, et al: Benefit of taxanes as adjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer: Pooled analysis of 15,500 patients. Cancer 106:2337-2344, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viani G, Afonso S, Stefano E, et al: Adjuvant trastuzumab in the treatment of her-2–positive early breast cancer: A meta-analysis of published randomized trials. BMC Cancer 7:153, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]