Abstract

Rod cone dysplasia type 2 (rcd2) is an autosomal recessive disorder that segregates in collie dogs. Linkage disequilibrium and meiotic linkage mapping were combined to take advantage of population structure within this breed, and to fine map rcd2 to a 230 kb candidate region that included the gene C1orf36 responsible for human and murine rd3, and within which all affected dogs were homozygous for one haplotype. In one of three identified canine retinal RD3 splice variants, an insertion was found that cosegregates with rcd2, and is predicted to alter the last 61 codons of the normal open reading frame and further extend the ORF. Thus combined meiotic linkage and LD mapping within a single canine breed can yield critical reduction of the disease interval when appropriate advantage is taken of within breed population structure. This should permit a similar approach to tackle other hereditary traits that segregate in single closed populations.

Keywords: dog genetics, progressive retinal atrophy, retinitis pigmentosa, linkage disequilibrium mapping

Introduction

The development of modern dog breeds has created a population structure that is largely separated into relatively closed subpopulations termed breeds. The traits that define each such breed include both those deliberately bred for, and undesirable traits concentrated into particular breeds by descent from a small founder pool. As information about the canine genome became increasingly available, it quickly became apparent that, in general, linkage disequilibrium (LD) within breeds can spread to several megabases, but across breeds LD only extends over tens of kilobases (Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005). This has suggested that the dog is particularly advantageous for gene mapping studies, as the large LD within a breed would require a correspondingly smaller number of markers for association mapping studies in dogs compared to humans (Sutter et al. 2004; Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005). Furthermore, when a trait segregates in multiple breeds, fine mapping across these breeds can very efficiently narrow the candidate region by taking advantage of the reduced LD interval common to all such breeds (Karlsson et al., 2007). Several identical-by-descent (IBD) mutations have been fine mapped in this manner (Neff et al. 2004; Goldstein et al. 2006; Sutter et al. 2007; Parker et al. 2007; Candille et al. 2007). In previous studies we employed this strategy to fine map two canine hereditary retinal disorders, collie eye anomaly (Parker et al. 2007) and progressive rod cone degeneration (Goldstein et al. 2006). Both of these diseases segregated in multiple breeds, and fine mapping between such breeds rapidly reduced the initially identified candidate region to yield the subsequently identified causative mutations (Zangerl et al. 2006; Parker et al. 2007). Retrospective analysis of these studies, however, suggested that in both cases, a careful selection of individuals based on population structure, would have resulted in the same progress, even if restricted to a single breed per disease. The significance of this observation has been strengthened by independent reports of stratified linkage disequilibrium within single breeds (Quignon et al. 2007; Bjornerfeldt et al. 2008). Successful implementation of this strategy would facilitate mapping and fine mapping of traits that are only known to segregate in single specific breeds.

Rod-cone dysplasia type 2 (rcd2) is one of the many canine hereditary retinal degenerations that are collectively named progressive retinal atrophy (PRA) (Aguirre and Acland 2006). Some forms of PRA are common to multiple dog breeds, while others are recognized in just a single breed (Acland et al. 1998; Acland et al. 1999; Zeiss et al. 2000; Kijas et al. 2002; Goldstein et al. 2006; Zangerl et al. 2006; Mellersh et al. 2006). As far as is known, rcd2 segregates exclusively in rough and smooth collies (Wolf et al. 1978). The disease is inherited as a simple autosomal recessive trait and has been previously characterized electrophysiologically, morphologically and biochemically (Santos-Anderson et al. 1980; Woodford et al. 1982; Chader et al. 1985; Acland et al. 1989). Night blindness is the earliest clinical sign detectable in 6-week-old affected dogs. Retinal dysfunction can be detected by electroretinography (ERG) as early as 16 days of age. At 6 weeks of age, when the photoreceptors of normal dogs are fully developed, only a few underdeveloped outer segments are visible in rcd2 dogs; by 2–2.5 months age, the outer segments completely disappear in the affected retina. Both rods and cones in the affected retina fail to develop normal outer segments (Santos-Anderson et al. 1980). Both types of photoreceptors subsequently degenerate, cones more slowly than rods. Ophthalmoscopic abnormalities can be detected at 3.5 to 4 months of age, including tapetal hyperreflectivity, retinal vascular attenuation and optic nerve pallor. By 6 to 8 months of age rcd2 dogs become functionally blind. The rcd2 locus has been mapped previously to a ~4 Mb region on CFA7, an interval homologous to human 1q32 (Kukekova et al. 2006).

In the present study a combination of meiotic linkage and linkage disequilibrium mapping, together with critical pedigree analysis, was employed to fine map and reduce this interval. Meiotic mapping utilized both additional, newly developed informative pedigrees, and additional microsatellite markers located within the previously identified zero recombination region. In parallel, a dense SNP map of the region was simultaneously developed to permit haplotype analysis and linkage disequilibrium mapping. In combination, these two approaches reduced the candidate region to an approximately 230 Kb interval on CFA7 that contained only three known genes (TRAF5, C1orf36, and SLC30A1). All three genes are retinal expressed and were thus potential positional candidates for rcd2. Comparative genomic analysis disclosed that the reduced canine rcd2 interval overlapped with the murine retinal degeneration 3 (rd3) locus on Mmu1 (Danciger et al. 1999). Simultaneously, and independently, the C1orf36 gene was identified as harboring the causative mutations for both murine rd3 and the homologous human disease (Friedman et al. 2006). This gene has now been renamed RD3. Sequence of the canine RD3 coding region was retrieved from retinal cDNA. Unlike mouse and human RD3, that each have a single known transcript (Lavorgna et al. 2003; Friedman et al. 2006), three canine retinal RD3 splice variants were detected. A sequence alteration identified in one of these variants between normal and rcd2 affected individuals is proposed as the cause of canine rcd2.

Methods

To fine map and reduce the rcd2 candidate region a 2-pronged approach was adopted. First, for meiotic linkage purposes the previously mapped families were significantly expanded (see below) to provide an additional 140 informative progeny. Both the previously mapped and newly developed pedigrees were then genotyped for a much denser set of microsatellites identified from the canine genome assembly as located within the region. Secondly, and simultaneously, a dense SNP map of the candidate region was developed to permit haplotype analysis and linkage disequilibrium mapping of the candidate region.

I. Pedigrees and DNA samples

Blood and or tissue samples were obtained from dogs in rcd2-informative collie-derived mixed-breed pedigrees developed at the Retinal Disease Studies Facility in Kennett Square, PA. Additional blood samples for DNA analysis were obtained from privately owned dogs representative of the USA pedigreed collie population. These pedigreed collies included both rough and smooth varieties of the breed. It should be noted that internationally these varieties are classified as separate breeds, and are not bred to each other, but they form a single breed registry in the USA. Extended pedigrees of rcd2-affected collies were obtained from historical records provided by collie breeders and analysed by inspection to detect patterns of common ancestry. Further blood samples for DNA analysis were obtained for population studies from privately owned dogs representing 19 other breeds. Samples used for meiotic linkage analysis represented 14 three-generation pedigrees (126 individuals in the informative generation) previously used for an rcd2 genome wide scan (Kukekova et al. 2006), and a further 26 backcross and intercross pedigrees including 140 informative progeny. LD mapping was performed using samples from 7 rcd2-affected and 3 rcd2-carrier (obligate-heterozygous) collie dogs. DNA from canine tissue samples (blood, spleen) was extracted using either Qiagen Mini and Maxi Blood kits (Qiagen, CA) or phenol-chloroform extraction methods (Gilbert and Vance 1994).

II. Microsatellite markers and linkage analysis

Three microsatellite markers (FH2226, FH3972, and VIASD10) were chosen that defined the previously identified rcd2 interval (Kukekova et al. 2006), plus a fourth (CPH20) from the corresponding interval of the canine integrated genome map (Guyon et al. 2003).

Potential additional microsatellites from this interval were identified from CanFam2 (the May 2005 assembly of the 7.6x canine genome sequence) using the RepeatMasker track of the UCSC browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway?org=Dog&db=canFam2), and primer pairs for each were designed using Primer3. Such potential markers were tested for informativeness on DNA representing four dogs from the parental generation of rcd2-informative pedigrees using standard PCR conditions: an initial 2 min denaturation at 96°C; then 30 cycles of 96°C (20 seconds), 58°C (20 seconds), 72°C (20 seconds); and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 minutes. PCR products were resolved on 10% native polyacrylamide gel and visualized by Ethidium bromide staining. Five such markers that proved polymorphic were selected for genotyping (SYT14F3/R3, SERTAD4F1/R1, KCNH1F3/R3, rcd2ms3F1/R1, rcd2ms6F1/R1; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Newly designed microsatellite markers and their locations on canine chromosome 7 (CFA7) in the CanFam2 assembly of the dog genome sequence.

| Primer | Primer sequence | Amplicon location |

|---|---|---|

| SYT14F3 | ctgcctgtgtctctgcctctctc | 11,599,574–11,599,748 |

| SYT14R3 | aatgtggagccccattttcaag | |

| SERTAD4F1 | acccctttctctccatgctagtgtc | 11,816,877–11,817,110 |

| SERTAD4R1 | gccttttcctgaacacctagtgacc | |

| KCNH1F3 | ggtctttagcttgccaactgcaga | 12,568,635–12,568,820 |

| KCNH1R3 | ctaacactgaatcagggttgacaga | |

| rcd2ms6F1 | tccagaattccttctccatctcag | 12,642,574–12,642,844 |

| rcd2ms6R1 | tccacagggattttgtctcaaaga | |

| rcd2ms3F1 | caaggatgggtcccttaaaacaga | 12,841,258–12,841,496 |

| rcd2ms3R1 | cagagggtctgacctatggcaagt |

For fine mapping and linkage analysis, pedigrees were genotyped with markers FH2226, CPH20, SYT14F3/R3, KCNH1F3/R3, FH3972, and VIASD10 using fluorescently labeled primers. PCRs were performed in a 15 μl mixture containing 1X Invitrogen Taq Polymerase buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2mM of dNTP, 0.3 pmol of each primer, 1.5 ng of canine DNA, and 0.5 units of Invitrogen Taq Polymerase. Amplification conditions were as described above for amplification with unlabeled primers except that the final extension time was for one hour. PCR products were combined into a multiplex set and analyzed on an ABI3730 capillary-based Genetic Analyzer (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR products were sized relative to an internal size standard (GeneScan 500 LIZ) using ABI Genemapper 3.5 software package (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quality parameters were established using ABI Genemapper 3.5 and genotypes were double scored by independent investigators.

III. SNP markers

SNP markers for the rcd2 interval were selected from the canine SNP database (http://www.broad.mit.edu/mammals/dog/snp/). Primers for amplification were designed using Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi). Identified SNPs were amplified on DNA from 3 to 7 rcd2 affected and 1 to 3 carrier dogs using the same PCR conditions described above for PCR with unlabeled primers. Robustly amplified PCR products were sequenced and analyzed using Sequencher software (Gene Codes Corporation, MI). Informative SNPs were used for haplotype analysis (Figure 1B, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1. High resolution meiotic linkage (A) and linkage disequilibrium (B) maps of the rcd2 interval on canine chromosome 7.

A. The map order of 9 microsatellites is indicated with their sequence locations in the CanFam2 assembly of the canine genome. For microsatellites FH2226, CPH20, FH3972 and VIASD10 the number of recombination events observed, between each marker and rcd2, per total number of informative individuals analyzed (126), is listed in parentheses below each marker’s name. SYT14, SERTAD4, KCNH1 and rcd2ms6 all cosegregated with each other, sharing 1 observed recombination with rcd2. Marker rcd2ms3 cosegregated with rcd2 with no observed recombinations.

B. CanFam2 locations and identifying names are listed for 38 SNPs identified in the rcd2 candidate region, as are genotypes for these SNPs from 4 rcd2-affected pedigreed collie dogs (I–IV). Shaded regions indicate where all 4 dogs share identical SNP genotypes. The region encompassed by the dashed box indicates the final rcd2 zero-recombination interval defined by the locations of markers rcd2ms6 and FH3972. The region boxed with a solid outline indicates the minimal region of absolute common LD, defined by the locations of SNP196 and SNP239. The final rcd2 candidate region, representing the overlap of the zero-recombination and absolute common LD intervals is indicated by SNP genotypes in bold.

IV. RNA

Total RNA was extracted from retinas of normal and rcd2 affected dogs using TRIZOL reagent (Ambion, TX). Time points included 1.4 to 1.9 weeks, 3.3 to 4.3 weeks, 6.4 to 7.9 weeks, and 9.7 to 10.3 weeks with a normal and rcd2 affected dog for each time point.

IV.1. RT-PCR

IV.1.a

To evaluate the rcd2 gene, primers for RT-PCR were designed from RD3 sequence retrieved from the 7.6x assembly of the canine genome (CanFam2), to cover the complete coding sequence (Table 2). Since the predicted exon 4 of this gene is missing from CanFam2 and it was not found in canine sequences from any other database, primers within exon 4 were designed from human RD3 sequence in regions highly conserved among human, mouse, chicken and opossum genomes. Once the canine sequence was retrieved from RT-PCR reactions, canine primers were designed to further improve the efficiency of reactions (Table 2A). cDNA was prepared using Thermoscript RT (Invitrogen, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol using an extension temperature of 600C. PCR reactions were run using GoTaq green master mix (Promega, WI) following the manufacturer’s protocol with 5% DMSO and annealing temperature in the range of 620C to 660C.

Table 2.

RD3 primers used for amplification of canine cDNA (A), for rcd2 mutation screening (B), and to develop hybridization probes (C). Primers RD3NH3F1 and RD3NH3R1 were designed for amplification of deaminated DNA.

| Primer | Sequence (5’ to 3’) | Source | Location | CanFam2.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Primers used to amplify canine RD3 cDNA | ||||

| 36R1A | gtggatcttggcacagacgtcctct | Canine | Canine exon 3 | 12,835,497–521 |

| 36F9 | cgcagtaacgcgctcaggaaggtct | Canine | Canine exon 3 | 12,835,601–625 |

| 36F18 | ccaggctggatccctccggtca | Canine | Canine exon 1 | 12,847,140–161 |

| 36R16 | agtcatctgaaggcactccagacct | Canine | Canine exon 6 | 12,820,212–236 |

| 36JR2 | gcagcgactacgcctccaggaacaat | Canine | 3’UTR v2 | 12,832,366–391 |

| 36e2R2 | cgctccacgtcctcggagatggt | Human | Human exon2 | |

| 36F2 | gtgctggagacgctcatgatgga | Canine | Canine exon 3 | 12,835,669–691 |

| 36R1 | gatcttggcacagacgtcctcta | Canine | Canine exon 3 | 12,835,500–522 |

| 36e2F3og | cggctcttccgctcggtgct | Canine | Canine exon 4 | Missing in CanFam2.0 |

| 36e2ogR16 | ggcgcccggaattcgggcatg | Human | Human exon 2 | |

| 36e2ogR13 | cggctttgggcgcccggaattc | Human | Human exon 2 | |

| 36BACR2 | ggaaggcccgctccctcccgtg | Canine | 3’UTR v3 | Missing in CanFam2.0 |

| 36JR3 | ctgaatctccagagccgcgacacc | Canine | Canine exon 4 | Missing in CanFam2.0 |

| 36e2F7og | ctcgcccttcgccggccacatc | Canine | Canine exon 4 | Missing in CanFam2.0 |

| 36e2F30 | ccccggccctggagcctgcg | Canine | Canine exon 4 | Missing in CanFam2.0 |

| 36e2R30 | gcaggctccaggtgcgcagc | Canine | Canine exon 4 | Missing in CanFam2.0 |

| 36e2R31 | cggaactcgggcaggctccaggtg | Canine | Canine exon 4 | Missing in CanFam2.0 |

| 36e2R32 | cctgcggcgcccggaactcg | Canine | Canine exon 4 | Missing in CanFam2.0 |

| B. Primers used to screen the rcd2 mutation | ||||

| RD3NH3F1 | tgagtgtgagtttgaggtgtatgagg | Canine | Canine exon 4 | Missing in CanFam2.0 |

| RD3NH3R1 | cacacacaaaacccacaaaaatcc | Canine | Canine exon 4 | Missing in CanFam2.0 |

| C. Primers used to produce PCR probes for BAC DNA hybridization | ||||

| RD3F2 | gtggtgtccatcctctgctggt | Canine | Canine exon 5 | 12,832,565–586 |

| RD3R2 | ccctacaggcttcgctgtcctt | Canine | Intronic sequence | 12,832,000–021 |

| RD3F4 | tgcaagagcccatagaacacca | Canine | Intronic sequence | 12,835,201–222 |

| RD3R4 | gtaaagggatgcagatccaccg | Canine | Intronic sequence | 12,834,685–706 |

| 36e2F1c | gttccggcagctgctggccga | Canine | Canine exon 4 | Missing in CanFam2.0 |

| 36e2ogR16 | ggcgcccggaattcgggcatg | Human | Human exon 2 | |

To identify the 5’ and 3’ ends of the transcript, 5’ RACE and 3’ RACE was undertaken on 10.4 weeks old normal canine retinal RNA using RACE kit BD Advantage following the manufacturer’s protocol (Clontech, CA). 5’ RACE-PCR with primer 36F9 and 3’ RACE-PCR with primer 36R1A were performed. PCR products were cloned into TOPO vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, CA). Two 3′ RACE and a 5′ RACE sequence were aligned using Sequencher, to identify an initial consensus canine RD3 cDNA sequence.

IV.1.b

TRAF5 retinal cDNA of one normal and one rcd2 affected dogs was amplified using RT-PCR with primers TR1F/TR1R, TR4F/TR3R, TR7F/TR10R, TR4F/TR7R, and TR6F/TR9R (Supplementary Table 2; NCBI Accession: EU687744).

IV.1.c

Partial canine SLC30A1 retinal cDNA was amplified using RT-PCR with primers SL1F/ SL3F/SL2R, SL6F/SL6R. Products corresponding to coding regions of the SLC30A1 gene were also amplified from canine genomic DNA using primers SL1F/SL1R, SL4F/SL3R, SL5F/SL5R (Supplementary Table 2). All products were amplified from retinal cDNA or genomic DNA from at least one normal and one rcd2-affected dog, and sequenced, NCBI Accession: EU687743.

IV.2. Northern analysis

Northern analysis was performed as described previously (Goldstein et al. 2006). Eleven retinal RNA probes from time points ranging from 1.4 weeks to 10.3 weeks old were analyzed. An RD3 probe was produced by amplification of cDNA with primers 36F18/36R1. The resulting probe comprises RD3 cDNA fragment from exon 1 through exon 3, primer location is listed in Table 2. The 737 bp PCR product was gel purified, cloned (TOPO TA cloning kit, Invitrogen, CA) and used for blot hybridization. Hybridization was carried out using Ultrahyb solution (Ambion, TX) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The blot was exposed to X-ray film at –700C for 72 hours using two intensifying screens. Loading control was achieved by hybridizing a canine β-actin probe to the membrane under the same conditions and exposure to X-ray film for 5 hours. Northern images were scanned on a Fuji Bio-Imaging Analyzer and scored by MacBAS software.

V. Cloning and sequencing of the gap region

To obtain sequence representing the genomic fragment of canine RD3 that is absent from the CanFam2 assembly, two canine BAC clones CH82-166H15 and CH82-417I05 (Boxer BAC library, http://bacpac.chori.org/library.php?id=253) were selected from the UCSC database (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). BAC DNA was digested with selected restriction enzymes and hybridized with canine RD3 probes #1 (RD3F2/R2) and #2 (RD3F4/R4) located before and after the gap in the CanFam2.0, respectively, and a probe #3 (36e2F1c/36e2ogR16) corresponding to a part of the canine RD3 exon 4. Primers used for probe amplification are listed in Table 2C. A PstI fragment, about 1.5 Kb, identified from BAC clone CH82-166H15, and tested positive for probes 1 and 3, and a PstI fragment ~4.5 Kb identified from BAC clone CH82-417I05 that was positive for probes 2 and 3, were both cloned into vector pUC19 at the corresponding restriction sites. The p166-18 plasmid (~1.5 Kb insertion) was sequenced using plasmid specific and RD3 specific primers (Supplementary Table 3). A large part of the p417–19 plasmid (~4.5 Kb insertion) was also sequenced in the same manner but the sequence failed to read through a GC-rich region of the insertion. To obtain this GC-rich sequence, the p417–19 plasmid was digested with restriction enzyme PvuII and an approximately 1.1 Kb fragment was subcloned into the pUC19 SmaI restriction site. The cloned fragment was sequenced using plasmid specific and RD3 specific primers (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 1). Sequence of the canine RD3 fragment corresponding to the 1,552 bp gap region in CanFam2 (CFA7: 12,832,685-12,834,236) was submitted to the NCBI database (NCBI Accession: EU687745).

VI. Mutation screening in normal and affected dogs

Because of the GC-rich nature of the canine RD3 gene (see below) genomic DNA was deaminated prior to PCR amplification using primer pair RD3NH3F1/RD3NH3R1 (see Table 2B). Deamination was undertaken using EZ Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol except that the deamination step was extended to 5 hours and the starting amount of DNA was reduced to 250 ng. PCR on deaminated DNA was performed under the following conditions: an initial 2 minutes denaturation at 96°C; then 30 cycles of 96°C (20 seconds), 58°C (20 seconds), 72°C (20 seconds); and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 minutes. PCR products were separated on 6% nondenaturing polyacrilamide gel. 18 rcd2 affected individuals, 13 rcd2 obligate carriers, and 110 dogs not known to be affected with rcd2 from 20 breeds were tested by PCR for presence of the RD3 insertion.

Results

I. Fine mapping the rcd2 locus

I.1. Linkage mapping

Six individuals from the previously published rcd2 pedigree set were recombinant in the ~4.0 Mb interval flanked by markers FH2226 and FH3972 (CFA7: 9,035,490 – 12,950,649 bp, CanFam2). Four of these, recombinant between FH2226 and rcd2, defined the centromeric end of the zero recombination interval. The other two, recombinant between rcd2 and FH3972 defined the telomeric end. Genotyping the pedigrees that included these recombinant offspring with additional informative microsatellite markers CPH20, REN314O07 and FH1031, identified one individual as recombinant between CPH20 and rcd2, thus shifting the centromeric boundary of the zero recombination interval, and reducing this interval to approximately 2.5 Mb (CFA7: 10,014,511 – 12,595,819 bp, CanFam2; Figure 1A).

Genotyping all previously identified recombinant individuals plus 22 additional rcd2-informative pedigrees (140 individuals) with 6 markers (CPH20, SYT14, SERTAD4, KCNH1, FH3972, and VIASD10) identified a recombination between rcd2 and centromerad marker KCNH1 (CFA7, Figure 2A; Table 1), but identified no further recombinations within the interval. Genotyping the pedigree that included this recombinant dog with another 2 markers (rcd2ms3 and rcd2ms6) established that its recombination was between rcd2ms6 and rcd2 (Figure 2A), which further reduced the rcd2 zero recombination interval to the approximately 308 Kb distance between markers rcd2ms6 and FH3972 (12,642,574–12,950,649 bp; Figure 1). This reduced interval included five known genes (RCOR3, GOLT1B, TRAF5, C1orf36 (RD3), and SLC30A1) on CanFam2.

Figure 2. Representative rcd2-informative experimental pedigree.

A. Pedigree demonstrates recombination between rcd2 and marker rcd2ms6, the closest marker recombinant with rcd2. + indicates the wild-type allele and - indicates the rcd2-disease allele. Haplotype shading indicates parental origin. Allele 4 for marker FH3972 in individual 7, marked by the asterisk (*) is an example of non-Mendelian inheritance.

B. Cosegregation of the RD3 insertional mutation in this rcd2 pedigree. All affected individuals (3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9) show one band (allele 1); all rcd2 carriers (1, 2, 4, 10) show two bands (alleles 1 and 2).

I.2. Pedigree Analysis, Haplotype Analysis and LD mapping

I.2. a. Pedigree Analysis

Pedigree analysis was undertaken on multiple rcd2-affected pedigreed collie dogs that were either founders of the rcd2-informative collie-derived pedigrees used for linkage mapping, or privately owned rcd2-affected pedigreed collies. From this analysis, the pedigrees of purebred collies could be separated into three distinct subpopulations. In the largest of these subpopulations, the pedigrees of rcd2-affected collies showed a similar pattern of several inbreeding loops within recent (4 to 10) generations, and all these dogs shared one or another of a small number of closely related recent common ancestors contributing to both their maternal and paternal lines of descent. As well, further descendants of these common ancestors included several additional dogs that were known historically to be affected with rcd2. This clearly suggested that the rcd2 disease alleles in this subpopulation were all inherited identical-by-descent from a recent common ancestor (data not shown).

In contrast, two rcd2-affected pedigreed collies each demonstrated very different pedigree structures, both from each other and from the majority of rcd2-affected pedigreed collies (i.e. from subpopulation 1). In both of these 2 dogs’ pedigrees there was a single inbreeding loop producing the affected dog, no further inbreeding loops were present within recent (4–6) generations, and no ancestor was recognized as being historically affected by PRA. In addition, neither of these 2 pedigrees included any dogs identified as recent common ancestors in the first subpopulation of rcd2 pedigrees. No ancestors were identified that were common to all 3 sets of pedigrees, within at least 13 generations (data not shown).

Because dogs from all three subpopulations had been used in development of the rcd2-informative collie-derived pedigrees, it was known that the diseases segregating in each of these lines were at least allelic, and probably represented inheritance identical-by-descent of a single allele from a much more ancient ancestor common to all 3 subpopulations.

I.2. b. Haplotype Analysis and LD mapping

To identify ancestral SNP haplotypes in phase with the rcd2 disease allele, 38 informative SNPs from the 2.57 Mb candidate region defined in the Figure 1B, with an average inter SNP distance of 45 Kb, were retrieved from the canine SNP database (http://www.broad.mit.edu/mammals/dog/snp) (Figure 1B; Supplementary Table 1). The SNPs were amplified and sequenced for a subset of rcd2-affected and -heterozygous dogs representing each of the 3 lines of descent described above.

Examination of the resulting SNP genotypes of rcd2-affected collie dogs representative of the 3 identified subpopulations revealed that all were homozygous throughout an extensive LD region (> 2Mb) surrounding the rcd2 locus, but the haplotypes compared between dogs differed markedly. (Figure 1B; Columns I–IV)

Dog I in Figure 1 was homozygous for (and thus demonstrates) the haplotype characteristic of the majority of rcd2-affected pedigreed collies, belonging to that subpopulation described above with pedigrees characterized by inbreeding loops involving recent common ancestors. Dog II in Figure 1 also belongs to the same subpopulation as Dog I, and shares the same genotype for all markers centromeric to SNP239. At SNP239 and further telomeric SNPs, however, this dog is heterozygous, clearly presenting evidence of an historic recombination event. Dogs III and IV in Figure 1 came from very different subpopulations, both from each other, and from Dogs I and II. Both dogs are homozygous for all SNPs within the tested interval, but their haplotypes are very different, both from each other, and from Dogs I and II.

The only interval in which all affected dogs shared identical alleles at all SNP loci was between SNP206 and SNP227. The boundaries of this region of common absolute LD, defined by flanking SNP196 centromerically and SNP239 telomerically, thus reduced the rcd2 candidate interval to less than 564 Kb.

I.3 Comparison of LD and meiotic linkage mapping results

The minimal common absolute LD region, identified above, thus exceeded 563 Kb, but its centromeric boundary was more distal (telomerad) than the corresponding limit identified by meiotic linkage mapping. The 308 Kb zero recombination interval, on the other hand, established a telomeric boundary that was further proximal (i.e. centromerad) that one defined by LD mapping. The overlap of these results jointly reduced the rcd2 candidate region to an approximately 230 Kb interval bounded by SNP206 at the centromeric end (from LD analysis), and FH3972 at the telomeric end (from meiotic linkage analysis). This interval corresponded to CFA7:12,724,381–12,950,649 on CanFam2, which included 3 known genes: TRAF5, C1orf36 (RD3), and SLC30A1.

II. Analysis of TRAF5 and SLC30A1 genes as positional candidates genes for rcd2

II.a. TRAF5

An entire open reading frame of the TRAF5 gene was amplified from the retinal cDNA of one normal and one rcd2 affected dog and sequenced. Comparison of the TRAF5 sequences detected one nucleotide difference between normal and rcd2 affected individuals. This polymorphism would not cause changes in the canine TRAF5 open reading frame. Alignment of the canine and human TRAF5 transcripts revealed 86% identity. The structure of the canine TRAF5 ortholog did not differ significantly from that of the human or mouse gene (data not shown).

II.b. SLC30A1

Partial screening of the coding region of the canine SLC30A1 gene (1,708 bp) was performed by amplification of retinal cDNA and gDNA from normal and rcd2 affected individuals. Sequence comparison identified several SNPs in the coding region of the canine SLC30A1 that were not associated with the disease (data not shown).

III. The canine RD3 gene and transcripts

The canine gene homologous to C1orf36 / RD3 was identified as annotated but incomplete on the reverse strand of CFA7 in CanFam2 between 12,847,668 and 12,831,626. This canine assembly included a 1,552 bp gap (CFA7:12,832,685–12,834,236) downstream from the region homologous to the first coding exon of the human gene (human exon 2). Alignment of sequence from the canine assembly with human and mouse demonstrated that the putative dog sequence appeared to be missing regions present in human and mouse, and could not be fully aligned to human coding sequence.

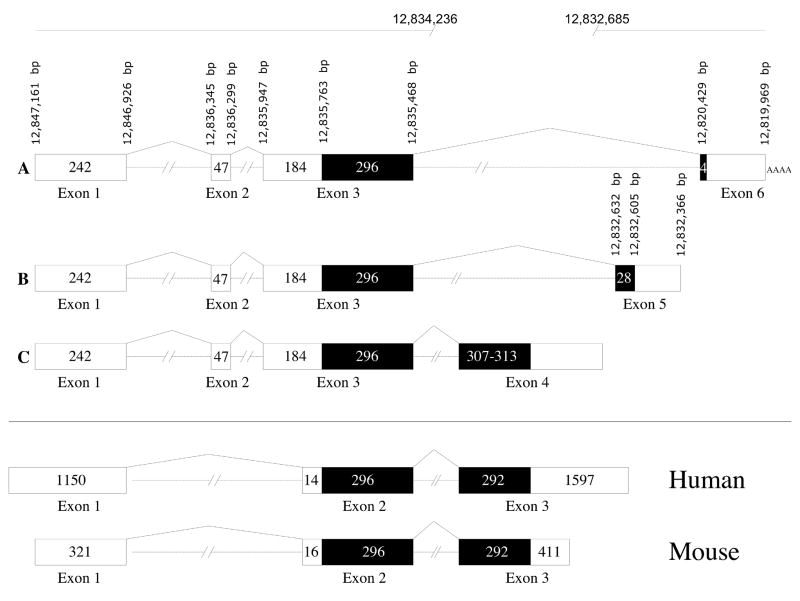

As described below, the canine gene proved, eventually, to comprise 6 exons, that are differentially spliced to yield 3 splice variants (Figure 3). Noncoding exon 1 of the dog corresponds to exon 1 of mouse and human, noncoding canine exon 2 does not appear to have a homolog in the other 2 species, and the first coding exon in the dog was canine exon 3 (corresponding to exon 2 of the human and mouse genes). Canine exon 4 (corresponding to exon 3 of the human and mouse genes, and the terminal coding exon in human and mouse) was apparently missing from the CanFam2 assembly. Canine exons 5 and 6 do not correspond to identified human or mouse exons.

Figure 3. Identified splice variants of canine RD3 transcripts.

Three splice variants of the canine RD3 gene are aligned against sequence locations on canine chromosome 7 in the CanFam 2 assembly of the dog genome, and compared to the orthologous human and mouse transcripts. Canine Exon 4 is not present in the CanFam2 assembly, as indicated by the gap from 12,834,236 tp 12,832,685. Open boxes correspond to the canine RD3 open reading frames, black boxes correspond to untranslated cDNA. A -splice variant #1; B - splice variant #2; C - splice variant #3. Not to scale.

III.a. RD3 splice variants number 1, 2 and 3

The initial canine RD3 transcripts were amplified and sequenced from retinal cDNA of a 10.4 week old normal dog, by 5’and 3’ RACE-PCR using primers 36R1A and 36F9, respectively (Table 2A), both located in the first coding exon and designed to produce overlapping 5’ and 3’ RACE amplicons. The coding sequence obtained by RACE was then confirmed using RT-PCR with primers 36F18 and 36R16. Blast of the resulting canine RD3 cDNA sequence against canine genomic DNA showed that this transcript comprised four exons which when aligned against CanFam2 were flanked by consensus splice donor and acceptor sites. This initially identified splice variant was predicted to encode a 99 amino acid protein with a start codon located in exon 3 and a stop codon located after the first base of the fourth exon of the transcript. The predicted length of canine protein was less than that of either the mouse or human, both of which comprise 195 amino acids. The exons comprising the dog transcript were eventually recognized as canine exons 1, 2, 3, and 6 (Figure 3A). The transcript did not include a canine homolog of the mouse and human exon 3 (Friedman et al., 2006, Figure 3, Supplementary Fig. 2) that would correspond to exon 4 in dog.

Amplification of normal retinal cDNA with primer pair 36F18 and 36JR2 identified a second splice variant (Figure 3B; Supplementary Fig. 2). This variant included exons 1, 2, 3, and a part of a new terminating exon eventually identified as canine exon 5. Alignment against genomic sequence confirmed that identified exons were flanked by consensus splice donor and acceptor sites. The sequence corresponding to exon 5 in this variant comprises 269 bp but this transcript likely extends beyond position of the primer 36JR2. This splice variant (number 2) was predicted to encode a 108 amino acid protein with a start codon located in exon 3 and a stop codon located after the first 28 bases of exon 5.

Based on the strong conservation of the second coding exon of RD3 among six mammalian species (Figure 4), we hypothesized that a canine RD3 splice variant that includes the ortholog of this exon (exon 3 in human and mouse) should exist in the canine retinal transcriptome. We further hypothesized that absence of this transcript from the above RACE results might be caused by competition among several splice variants for shared primers, and/or because of the GC-richness of this exon in humans and mouse (68% and 66% GC respectively). Because this region of the canine RD3 gene is not present in the CanFam2 assembly, a human sequence primer (36e2R2) was designed from alignment of human and mouse exons 3, and used in conjunction with primer 36F2 (canine sequence, canine exon 1) to amplify normal canine retinal cDNA by RT-PCR. This yielded a 458 bp product that was highly similar to human and mouse RD3 exons 2 and 3 (Figure 4). Because this new, but partial splice variant (splice variant 3) clearly established the existence of canine exon 4 (canine homolog of human and mouse exon 3), which was not present in the CanFam2 assembly, we proceeded to sequence the two plasmids p166-18 and p417–19 (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 3). As described in the Methods, section V, these plasmids were subcloned from 2 canine BAC clones, and were expected to cover the 1,552 bp gap region in the CanFam2 assembly. Subcloning and sequencing of these genomic fragments from the BAC clones have been pursued because multiple attempts to obtain this sequence using long range PCR have been unsuccessful. Sequence obtained from these plasmids included the newly identified canine RD3 exon 4 and its flanking region (NCBI Accession: EU687745).

Figure 4. Alignment of canine RD3 exon 4 to the corresponding exon from seven other species.

Nucleotides that differ from the human sequence are colored in grey. Two nucleotides in the dog sequence (positions 122–123) that serve as left and right boundaries of the insertion in the rcd2 affected dogs are in bold and underlined.

Using forward primer 36F18 (located in canine exon 1), and reverse primer 36BACR2, located in the predicted 3’ UTR downstream of the stop codon in newly identified canine exon 4, a more complete version of splice variant number 3, that covered the entire CDS and partial 3′UTR, was amplified from normal retinal cDNA by RT-PCR. This splice variant contains exons 1, 2, 3, and 4 (Figure 3C) and is predicted to encodes either a 200 or 202 amino acid protein -- a polymorphic repeat identified in exon 4 of several normal dogs (2 versus 3 copies of a hexamer repeat; Figure 5; Supplementary Fig. 2) determines the predicted deletion or insertion of two amino acids (arginine, proline).

Figure 5. Canine RD3 coding sequences demonstrating variations among normal and rcd2 affected dogs.

The nucleotide sequence of the wildtype open reading frame is shown with the corresponding translated amino acid sequence underneath, in italics. The start codon and the normal stop codon are bolded. The junction of exons three and four is represented by the backslash (G\G). A hexamer repeat is indicated within square brackets and shaded  . Sequence variants with either two or 3 copies of this hexamer are observed from normal dogs; the rcd2-disease allele has 2 copies. This hexamer codes for a pair of amino acids (R P), which are thus predicted to be present twice or 3 times in the translated sequence. The boxed nucleotide

. Sequence variants with either two or 3 copies of this hexamer are observed from normal dogs; the rcd2-disease allele has 2 copies. This hexamer codes for a pair of amino acids (R P), which are thus predicted to be present twice or 3 times in the translated sequence. The boxed nucleotide  represents a SNP (S = C or G), both alleles being observed in normal dogs, that changes the coded amino acid

represents a SNP (S = C or G), both alleles being observed in normal dogs, that changes the coded amino acid  from proline to arginine. The rcd2-disease sequence has the G allele for this SNP. The asterisk (*) marks the site (immediately before the polymorphic nucleotide indicated by

from proline to arginine. The rcd2-disease sequence has the G allele for this SNP. The asterisk (*) marks the site (immediately before the polymorphic nucleotide indicated by  ) where a 22 bp sequence (

gcccgcccccgcccccgccccc) is inserted in the rcd2 disease allele.

) where a 22 bp sequence (

gcccgcccccgcccccgccccc) is inserted in the rcd2 disease allele.

III.b. Identification of the rcd2 mutation

Attempts to amplify fragments of canine RD3 from affected dogs were initially highly inconsistent. One primer pair (36F18, 36JR3) robustly amplified retinal cDNA from both normal and rcd2 affected individuals. Primers downstream from 36JR3, however, failed to amplify an affected amplicon either by RT-PCR of cDNA, or by genomic PCR.

Because the normal allele of canine RD3 exon 4 is over 80% GC-rich, we hypothesized that a mutation in the corresponding affected allele might be responsible for the difficulty in amplification of this region. To address this possibility, we deaminated genomic DNA from normal, rcd2 affected, and rcd2 carrier dogs using EZ Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research, CA). Deaminated DNA was amplified with primers RD3NH3F1/ RD3NH3R1 and sequenced. Complete absence of cytosine residues in the final sequence indicated that deamination was complete. Comparison of deaminated sequences revealed a 22 bp insertion in the affected amplicon, that causes a frame shift and continues the open reading frame beyond the normal stop codon.

To retrieve further downstream sequence of the disease allele of splice variant 3, PCR was undertaken on genomic DNA from an affected dog using four primer sets (36e2F7og/36BACR2, 36e2F30/36e2R30, 36e2F30/36e2R31, 36e2F30/36e2R32). Assembled sequence from the resulting overlapping fragments included the continuation of canine exon 4 and a part of the 3’UTR of splice variant 3, but sequencing failed consistently for regions downstream of primer 36BACR2, located 39 bp downstream from the normal stop codon. Comparison of the coding sequences of RD3 splice variant 3 from normal and rcd2 affected dogs predicts that the 22 bp insertion changes the last 61 amino acids of the encoded protein (Figure 5). From analysis of genomic DNA sequence representing the normal 3’UTR sequence for this splice variant, the affected transcript is predicted to encode a total of 574 amino acids.

IIIc. RD3 expression in normal and mutant canine retinas

Northern analysis was undertaken to examine RD3 expression in normal and rcd2 affected canine retinas at different stages of postnatal development. In normals there was an abundant transcript over 2.37 Kb detected as early as 1.9 weeks of age (the earliest time point studied), the time when photoreceptors just beginning to differentiate in the central retina; the highest level of expression was detected at 6.4 weeks of age, when retinal differentiation is near completion (Aguirre et al. 1982; Acland and Aguirre 1987; Figure 6). Trace amounts of a similarly sized RD3 transcript was observed in all lanes from rcd2-affected retina (Figure 6). Less abundant signals corresponding to about 4.4 and about 7.5 Kb were also observed in both normal and affected RNA samples. There was no significant difference in intensity of these signals between normal and affected dogs. Hybridization with a β-actin probe was used to permit comparison of RNA loading between lanes.

Figure 6. RD3 Expression in canine retina.

A. Northern blot analysis of RD3 expression in total retinal RNA from normal (lanes 1, 4, 5, 7, 10) and rcd2 affected (lanes 2, 3, 6, 8, 9, 11) dogs at selected postnatal age points. Lanes 1= 1.4; 2 and 3 = 1.9; 4 = 3.3; 5 = 4.3; 6 = 4.1; 7 = 6.9; 8 = 6.4; 9 = 7.9; 10 = 9.7; and 11 = 10.0 weeks of age. Ribosomal RNA is indicated as 28S and 18S. B. Northern analysis of the same RNA blot with β-actin probe.

IV. Population analysis of RD3 mutation

To confirm that the RD3 insertion co-segregated with the rcd2 disease phenotype we genotyped individuals from several rcd2 informative pedigrees using primers RD3NH3F1 and RD3NH3R1 (Table 2B). Complete co-segregation of the RD3 insertion allele with the rcd2 phenotype was observed (Figure 2B).

To test this association further, a population study was undertaken using 18 rcd2-affected, 13 obligate heterozygous, and 49 clinically nonaffected pedigreed collie dogs that were neither part of, nor closely related to the primary study population, and a further 61 clinically nonaffected dogs representing 19 other (i.e. non-Rough or Smooth collies) breeds. All rcd2 affected dogs were homozygous for the RD3 insertion, all obligate carriers carried both normal and affected alleles, one clinically nonaffected collie dog was heterozygous, and all other clinically nonaffected dogs tested were homozygous for the normal RD3 allele. (Table 3, Supplementary Table 4).

Table 3.

Test results of mutation screening in a population of rcd2 affected, carrier, and normal dogs.

| rcd2 status | Affected | Obligate carriers | Clinically nonaffected Collies | Clinically nonaffected dogs, other breeds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of chromosomes tested | 36 | 26 | 98 | 122 |

| Number of RD3 insertion alleles identified | 36 | 13 | 1 | 0 |

Discussion

To fine map the canine rcd2 interval, a combination of meiotic linkage and linkage disequilibrium mapping was instrumental in reducing the candidate interval to manageable proportions. This was successful in concentrating attention to the canine homolog of C1orf36 / RD3, and led to identification of the insertion proposed as the causative mutation. At the same time, this effort brought into focus critical issues in undertaking LD/association studies in a canine population.

Fine mapping by meiotic linkage analysis was undertaken using 42 mixed-breed backcross and intercross pedigrees derived from multiple rcd2-affected founders, including 266 offspring in the informative generation. These pedigrees were densely mapped with a set of polymorphic microsatellite markers across the previously identified rcd2 zero recombination interval (Kukekova et al. 2006). This effort reduced the rcd2 interval to ~308 Kb, with the centomerad boundary of the new interval defined by a single observed recombinant event.

Simultaneously, a SNP genotyping effort was undertaken to identify haplotypes cosegregating with the rcd2 disease allele. The set of rcd2-affected individuals to genotype was selected based on ancestry analysis. The pedigrees of most rcd2-affected collies all shared a small number of ancestors contributing to both their maternal and paternal lines of descent within recent (4 to 10) generations. Several such dogs were among the founders of the rcd2-informative collie-derived pedigrees used in this study. In contrast, two rcd2-affected pedigreed collies that were also used in the study colony, were outliers. They were each the result of an inbred mating, but their pedigrees included none of the dogs previously identified as common ancestors in rcd2 segregating pedigrees and, including these 2 dogs in the analysis, no ancestors common to all lines of descent were identified within at least 13 generations.

The SNP genotyping results were initially surprising. Comparison of genotypes representative of the majority of rcd2-affected pedigreed collies (Figure 1B, Dog I), with those of the 2 outlier dogs (Figure 1B, Dogs III and IV) revealed that all these dogs were homozygous for all SNPs tested over at least 2.5 Mb. However, the haplotypes differed significantly among these dogs. As fine mapping of the rcd2-interval with SNPs continued, concentrating on the zero recombination interval, a minimal common LD region emerged in which the same haplotype was shared by all rcd2-affected dogs. One rcd2-affected collie (Figure 1B, Dog II) from the same subpopulation as Dog I revealed an historic recombination event between SNP227 and SNP239, that defined the telomeric end of the common absolute LD interval. The centromeric end of the absolute LD interval was also defined by a historical recombination between SNP196 and SNP206 (see Dog III, Figure 1B) making the length of this interval approximately 563 Kb.

Comparison of meiotic linkage analysis and LD results reduced the final rcd2 candidate interval to about 230 Kb - a region that included only three recognized genes. This demonstrates the efficiency of applying a combination of linkage and LD mapping for high resolution mapping a monogenic trait in dogs and highlights advantages and limitations of both approaches. Linkage analysis in canine populations is frequently limited by the availability of suitable informative pedigrees, particularly for purposes of fine mapping, and, in some cases, low level of recombination. To refine a mapped disease locus to an interval less than 1 Mb, pedigrees with well over 200 informative progeny may be required. Such pedigrees are rarely available -- in the present study the pedigrees were derived from carefully bred colony dogs, and could be expanded relatively rapidly as needed, but such a resource is not generally available for the majority of traits segregatig in dogs. As our data shows, however, once a phenotype is mapped to a broad interval, LD mapping of a few carefully selected individuals can reduce the interval dramatically even if the disease is observed in a single breed.

The reported extensive LD within dog breeds has been broadly taken to indicate that genome wide association studies can be undertaken at relatively low resolution within a single canine breed, and then refined using the narrower LD between breeds. Indeed, this approach has had several notable successes (Goldstein et al. 2006; Zangerl et al. 2006; Parker et al. 2007; Karlsson et al., 2007; Sutter et al. 2007). However, the present study indicates that such a strategy could well fail for a disease like rcd2 that segregates within a single breed. On the other hand, our study shows that by careful selection of dogs to genotype based on pedigree analysis, that a two stage LD analysis can be effective, even within a single canine breed. A low resolution association study to detect LD -- for example. using currently available resources for genome wide SNP-based association studies in dogs (Karlsson et al., 2007) --would probably have failed to identify the rcd2 associated region if it included a mixture of dogs like dogs I, III, and IV in Figure 1. But a structured association study looking first at the dogs with recent common ancestors, and subsequently and separately at the least related rcd2-affected dogs, would have been successful.

This observation confirms a growing recognition (Goldstein et al. 2006; Parker et al. 2007; Quignon et al. 2007; Bjornerfeldt et al. 2008) that pedigree structure within dog breeds can increase the power of association mapping studies. Several recent studies have shown that even for diseases observed in multiple breeds, the LD interval can be reduced by comparison of haplotypes of carefully selected, least related individuals from one breed to an extent comparable to that achieved by comparison of haplotypes across multiple breeds. As examples, the minimal LD interval for CEA, a disease recognized in multiple dog breeds, was reduced to 103 Kb mostly by haplotype comparison among unrelated affected Border Collies (Parker et al. 2007); the LD interval for prcd, another multibreed disease, was reduceable to 106 Kb largely by comparison of haplotypes of unrelated Australian Cattle Dogs and Toy Poodles from different countries (Goldstein et al. 2006); and in the Golden Retriever breed, with a large population and diverse pedigree structure, selection of dogs originating from different geographical regions was able to yield a 25% decrease in LD, comparable to the LD reduction when haplotypes from two distinct breeds were combined (Quignon et al. 2007). In the current study a dramatic reduction of the rcd2 interval was achieved with only three samples of the same geographical origin from one breed. This demonstrates that a disease segregating in just a single breed can be mapped efficiently by LD mapping, if breed size, structure, and history are appropriately taken into account. Similar mapping strategy can be predicted to be applicable for other species with well established breed structure (Gautier et al. 2007; Menotti-Raymond et al. 2008; O’Brien et al. 2008; Amaral et al. 2008).

The canine RD3 gene has several features unlike that of the corresponding human and mouse genes. Not only are there additional exons and splice variants detected in the dog, but the extreme GC richness of canine exon 4 (corresponding to human and murine exon 3) also posed challenges for cloning and sequencing. The latter issue presumably accounts for the gap (CFA7: 12,832,685–12,834,236) in CanFam2 corresponding to this part of the genomic sequence. This sequence, eventually retrieved from BAC clones, posed even greater difficulties for screening rcd2-affected dogs. However, sequencing this exon from normal and rcd2 affected dogs after amplification of deaminated DNA identified a 22 bp insertion in the disease allele.

Three canine RD3 retinal splice variants were identified (Figure 3, Supplementary Fig. 2), only one of which (splice variant 1) has as yet a completely sequenced 3’UTR, as assessed by the identification of a poly-A tail. How far the 3’ UTR of transcripts 2 and 3 extend is unclear, as attempts to RACE-PCR amplify them failed, and the presently reported 3’ end of sequence for each of these splice variants is truncated by the RT-PCR primer.

Repeated attempts to sequence the disease allele of exon 4 retrieved only 39 bases downstream from the normal stop codon. Because the reading frame remained open through exon 4 to this point, it is clear that the insertion alters the predicted peptide sequence corresponding to the last 61 amino acids of the normal protein, and may add a further 372 amino acids, if one assumes that the further downstream sequence of the exon 4 disease allele is the same as in the normal allele.

Northern analysis revealed one abundant RD3 transcript, ~2.4 Kb, in retinal RNA of normal dogs at all developmental stages tested (Figure 6). Only trace amounts of this transcript were detected in rcd2 affected individuals. Further larger bands, about 4.4 and 7.5 Kb, were also observed on the northern, but their intensity did not vary significantly among samples representing different developmental stages, nor between normal and affected individuals; additional studies would be required to verify which band corresponds to which splice variant. However, based on the difference between normal and affected seen in northern analysis, the ~2.4 Kb band probably corresponds to splice variant 3, which is the only one containing the disease-causing insertion. We hypothesize that this transcript may either be unstable in affected dogs, or its high GC content makes it difficult for the cell to transcribe.

Detection of three splice variants of canine RD3 gene differs from reports on human and mouse RD3 in which only a single transcript was described (Lavorgna et al. 2003; Friedman et al. 2006). The RD3 transcript is detectable in mouse retinal RNA at a very low level at E12 with an increase in expression at E18, and a further increase at P2 and P6, after which expression level remains high (Friedman et al. 2006). In normal dogs, the lowest expression level of the ~2.4 Kb RD3 transcript was observed at 1.4 weeks of age (the earliest time point studied) with levels increasing to 7 weeks postnatal, when photoreceptor differentiation is approaching maturity in the canine retina (Acland and Aguirre 1987). The presence of several RD3 transcripts in the canine retina may suggest that the RD3 gene has several functions in the retina.

A C319T mutation in exon 3 of the mouse RD3 gene, resulting in a predicted stop codon after residue 106, has been reported as the causative mutation for the rd3 mouse phenotype (Friedman et al. 2006). Canine exon 4 -- mutated in rcd2, and mouse exon 3 -- mutated in rd3 -- are orthologous. RD3 mutations have also been reported in two human patients, siblings, both affected with the early onset retinopathy Leber congenital amaurosis; in these cases mutations were present in the donor splice site at the end of human exon 2 (Friedman et al. 2006).

The function of the RD3 gene is not well understood. In silico analysis of mouse and human RD3 proteins revealed a coiled-coil domain at amino acids 22–54 and another weaker coiled-coil domain at aa 121–141. Several putative protein kinase C and consensus Casein kinase II phosphorylation sites and one predicted sumoylation site have been identified in the RD3 protein (Friedman et al. 2006). In transfected COS-1 cells, the RD3-GFP–fusion protein primarily exhibits nuclear or nuclear / cytoplasmic localization in close proximity to promyelocytic leukemia (PML) bodies (Friedman et al. 2006). Identification of the mutation responsible for rcd2 reinforces the significance of the role that RD3 plays in retinal function and development, although the specific functions need to be identified.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. 1. Cloning a gap in the canine RD3 genomic sequence.

To isolate and sequence genomic DNA covering a 1,552 bp gap (CFA7: 12,832,685–12,834,236) in the CanFam2 genomic assembly, BAC clones CH82-166H15 and CH82-417I05 were identified as tiling across the region.

PstI digestion of DNA from BAC clone CH82-166H15 identified a 1564 bp fragment that tested positive for RD3 probes 1 and 3 (see Table 2C). This fragment was subcloned as plasmid p166-18 and sequenced using plasmid specific and RD3 specific primers (Supplementary Table 3). This sequence extends the canine genomic sequence from position 12,835,324 bp to nucleotide number 68 in canine RD3 exon 4.

PstI digestion of DNA from BAC clone CH82-417I05 identified a restriction fragment about 4,500 bp that tested positive for RD3 probes 2 and 3 (see Table 2C). This fragment was subcloned as plasmid p417–19, and similarly sequenced. A 1.1 Kb PvuII restriction fragment from the plasmid p417–19 insert was also subcloned and sequenced to complete the assembly through a particularly GC-rich region. Sequence derived from plasmid p417–19 extended from nucleotide number 69 in canine RD3 exon 4 to position 12,828,624 bp in the CanFam2 canine genomic sequence.

Because the canine RD3 gene is on the reverse strand of the dog genome, the cloned region is presented on the figure as 12,835,324–12,828,624 bp.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Sequence of canine RD3 exons and splice variants identified in normal canine retinal cDNA.

A. Nucleotide Sequence of Identified Exons

The predicted start codon in exon 3 and stop codons in exons 4, 5, and 6 are boxed and bolded. Polymorphisms are shaded, with superscripted numerals indicating the nature of each polymorphism.

1 = SNP (Y= C or T, S= C or G, M= A or C, R= A or G); 2 = indel; 3 = hexamer repeat: either 2 or 3 copies of the repeat motif are observed.

B. Predicted translation of canine RD3 splice variants

Two predicted polymorphisms in the encoded amino acid sequence of splice variant 3 are shaded. The bracketed and shaded RP sequence (superscripted with numeral 4) corresponds to the hexamer repeat observed in the nucleotide sequence of exon 4. Either 4 or 6 copies of this RP motif are predicted to correspond to the presence of either 2 or 3 copies of the hexamer, respectively. The shaded amino acid P, superscripted with numeral 5, will be either P or R corresponding to the polymorphic nicleotide in the corresponding codon in exon 4.

Supplementary Table 1. Primers used for amplification and sequencing of SNPs from the rcd2 interval

Supplementary Table 2. Primers used for cloning and sequencing of TRAF5 and SLC30A1 cDNA.

Supplementary Table 3. RD3-specific primers used for sequencing cloned restriction fragments from BACs CH82-166H15 and CH82-417I05. Sequence was generated to fill the 1,552 bp gap (CFA7: 12,832,685–12,834,236) in the CanFam2 genomic assembly, corresponding to canine RD3 exon 4 and flanking sequence.

Supplementary Table 4. Distribution of RD3 insertion allele in populations of rcd2-affected, carrier, and normal dogs. Tested breeds include 80 Rough and Smooth collies; 5 Border collies; 4 Australian cattle dogs; 4 American Eskimo, 1 Boxer, 2 Elkhounds; 3 mixed breed dogs; 4 Golden retrievers; 5 Labrador retrievers; 4 Portuguese water dogs; 4 Chinese crested; 4 Samoyed; 3 Novia Scotia duck tolling retrievers; 1 English cocker spaniel; 1 Entlebucher mountain dog; 1 English mastif; 4 Chesapeake Bay retrievers; 2 American cocker spaniels; 4 Glen of Imaal terriers; 2 Basenjis; 3 Poodles.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Amanda Nickle, Gerri Antonini, and the staff of the RDS facility for research support. This study was supported by EY006855, MH077811, Foundation Fighting Blindness, Morris Animal Foundation, Collie Health Foundation, and Cornell VERGE Initiative. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the supporting institutions or foundations.

Footnotes

References

- Acland GM, Aguirre GD. Retinal degenerations in the dog: IV. Early retinal degeneration (erd) in Norwegian elkhounds. Exp Eye Res. 1987;44:491–521. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(87)80160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acland GM, et al. Nonallelism of 3 Genes (rcd1, rcd2 and erd) for Early Onset Hereditary Retinal Degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 1989;49:983–998. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(89)80021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acland GM, et al. Linkage analysis and comparative mapping of canine progressive rod-cone degeneration (prcd) establishes potential locus homology with retinitis pigmentosa (RP17) in humans. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3048–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acland GM, et al. A Novel Retinal Degeneration Locus Identified by Linkage and Comparative Mapping of Canine Early Retinal Degeneration. Genomics. 1999;59:134–142. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre GD, et al. Retinal degeneration in the dog. III. Abnormal cyclic nucleotide metabolism in rod-cone dysplasia. Exp Eye Res. 1982;35:625–42. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(82)80075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre GD, Acland GM. Models, mutants and man: Searching for unique phenotypes and genes in the dog model of inherited retinal degeneration. In: Ostrander EA, Giger U, Lindblad-Toh K, editors. The Dog and its Genome. Cold Spring Harbor; Cold Spring Harbor: 2006. pp. 291–325. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral AJ, et al. Linkage disequilibrium decay and haplotype block structure in the pig. Genetics. 2008;179:569–79. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.084277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornerfeldt S, et al. Assortative mating and fragmentation within dog breeds. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candille SI, et al. A -defensin mutation causes black coat color in domestic dogs. Science. 2007;318:1418–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1147880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chader GJ, et al. A review of the role of cyclic GMP in neurological mutants with photoreceptor dysplasia. Curr Eye Res. 1985;4:811–9. doi: 10.3109/02713688509020039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danciger JS, et al. Genetic and physical maps of the mouse rd3 locus; exclusion of the ortholog of USH2A. Mamm Genome. 1999;10:657–61. doi: 10.1007/s003359901067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JS, et al. Premature truncation of a novel protein, RD3, exhibiting subnuclear localization is associated with retinal degeneration. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:1059–70. doi: 10.1086/510021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier M, et al. Genetic and haplotypic structure in 14 European and African cattle breeds. Genetics. 2007;177:1059–70. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.075804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JR, Vance JM. Isolation of genomic DNA from mammalian cells. In: Haines JL, et al., editors. Current Protocols in Human Genetics. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1994. pp. 1–6. Appendix A.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein O, et al. Linkage disequilibrium mapping in domestic dog breeds narrows the progressive rod-cone degeneration interval and identifies ancestral disease-transmitting chromosome. Genomics. 2006;88:551–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon R, et al. A 1 Mb resolution radiation hybrid map of the canine genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5296–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831002100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson EK, et al. Efficient mapping of mendelian traits in dogs through genome-wide association. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1321–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kijas JW, et al. Naturally occurring rhodopsin mutation in the dog causes retinal dysfunction and degeneration mimicking human dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6328–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082714499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukekova AV, et al. Linkage mapping of canine rod cone dysplasia type 2 (rcd2) to CFA7, the canine orthologue of human 1q32. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1210–5. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavorgna G, et al. Identification and characterization of C1orf36, a transcript highly expressed in photoreceptor cells, and mutation analysis in retinitis pigmentosa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;308:414–21. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01410-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblad-Toh K, et al. Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog. Nature. 2005;438:803–19. doi: 10.1038/nature04338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellersh CS, et al. Canine RPGRIP1 mutation establishes cone-rod dystrophy in miniature longhaired dachshunds as a homologue of human Leber congenital amaurosis. Genomics. 2006;88:293–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti-Raymond M, et al. Patterns of molecular genetic variation among cat breeds. Genomics. 2008;91:1– 11. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff MW, et al. Breed distribution and history of canine mdr1-1Delta, a pharmacogenetic mutation that marks the emergence of breeds from the collie lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11725–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402374101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien SJ, et al. State of cat genomics. Trends Genet. 2008;24:268–79. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker HG, et al. Breed relationships facilitate fine-mapping studies: a 7.8-kb deletion cosegregates with Collie eye anomaly across multiple dog breeds. Genome Res. 2007;17:1562–71. doi: 10.1101/gr.6772807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quignon P, et al. Canine Population Structure: Assessment and Impact of Intra-Breed Stratification on SNP-Based Association Studies. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Anderson R, et al. An inherited retinopathy in collies: a light and electron microscopic study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1980;19:1281–1294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter NB, et al. Extensive and breed-specific linkage disequilibrium in Canis familiaris. Genome Res. 2004;14:2388–96. doi: 10.1101/gr.3147604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter NB, et al. A single IGF1 allele is a major determinant of small size in dogs. Science. 2007;316:112–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1137045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ED, et al. Rod-cone dysplasia in the collie. Journal American Veterinary Medical Association. 1978;173:1331–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodford B, et al. Cyclic nucleotide metabolism in inherited retinopathy in collies: a biochemical and histochemical study. Exp Eye Res. 1982;34:703–714. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(82)80031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangerl B, et al. Identical mutation in a novel retinal gene causes progressive rod-cone degeneration in dogs and retinitis pigmentosa in humans. Genomics. 2006;88:551–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiss CJ, et al. Mapping of X-linked progressive retinal atrophy (XLPRA), the canine homolog of retinitis pigmentosa 3 (RP3) Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:531–7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1. Cloning a gap in the canine RD3 genomic sequence.

To isolate and sequence genomic DNA covering a 1,552 bp gap (CFA7: 12,832,685–12,834,236) in the CanFam2 genomic assembly, BAC clones CH82-166H15 and CH82-417I05 were identified as tiling across the region.

PstI digestion of DNA from BAC clone CH82-166H15 identified a 1564 bp fragment that tested positive for RD3 probes 1 and 3 (see Table 2C). This fragment was subcloned as plasmid p166-18 and sequenced using plasmid specific and RD3 specific primers (Supplementary Table 3). This sequence extends the canine genomic sequence from position 12,835,324 bp to nucleotide number 68 in canine RD3 exon 4.

PstI digestion of DNA from BAC clone CH82-417I05 identified a restriction fragment about 4,500 bp that tested positive for RD3 probes 2 and 3 (see Table 2C). This fragment was subcloned as plasmid p417–19, and similarly sequenced. A 1.1 Kb PvuII restriction fragment from the plasmid p417–19 insert was also subcloned and sequenced to complete the assembly through a particularly GC-rich region. Sequence derived from plasmid p417–19 extended from nucleotide number 69 in canine RD3 exon 4 to position 12,828,624 bp in the CanFam2 canine genomic sequence.

Because the canine RD3 gene is on the reverse strand of the dog genome, the cloned region is presented on the figure as 12,835,324–12,828,624 bp.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Sequence of canine RD3 exons and splice variants identified in normal canine retinal cDNA.

A. Nucleotide Sequence of Identified Exons

The predicted start codon in exon 3 and stop codons in exons 4, 5, and 6 are boxed and bolded. Polymorphisms are shaded, with superscripted numerals indicating the nature of each polymorphism.

1 = SNP (Y= C or T, S= C or G, M= A or C, R= A or G); 2 = indel; 3 = hexamer repeat: either 2 or 3 copies of the repeat motif are observed.

B. Predicted translation of canine RD3 splice variants

Two predicted polymorphisms in the encoded amino acid sequence of splice variant 3 are shaded. The bracketed and shaded RP sequence (superscripted with numeral 4) corresponds to the hexamer repeat observed in the nucleotide sequence of exon 4. Either 4 or 6 copies of this RP motif are predicted to correspond to the presence of either 2 or 3 copies of the hexamer, respectively. The shaded amino acid P, superscripted with numeral 5, will be either P or R corresponding to the polymorphic nicleotide in the corresponding codon in exon 4.

Supplementary Table 1. Primers used for amplification and sequencing of SNPs from the rcd2 interval

Supplementary Table 2. Primers used for cloning and sequencing of TRAF5 and SLC30A1 cDNA.

Supplementary Table 3. RD3-specific primers used for sequencing cloned restriction fragments from BACs CH82-166H15 and CH82-417I05. Sequence was generated to fill the 1,552 bp gap (CFA7: 12,832,685–12,834,236) in the CanFam2 genomic assembly, corresponding to canine RD3 exon 4 and flanking sequence.

Supplementary Table 4. Distribution of RD3 insertion allele in populations of rcd2-affected, carrier, and normal dogs. Tested breeds include 80 Rough and Smooth collies; 5 Border collies; 4 Australian cattle dogs; 4 American Eskimo, 1 Boxer, 2 Elkhounds; 3 mixed breed dogs; 4 Golden retrievers; 5 Labrador retrievers; 4 Portuguese water dogs; 4 Chinese crested; 4 Samoyed; 3 Novia Scotia duck tolling retrievers; 1 English cocker spaniel; 1 Entlebucher mountain dog; 1 English mastif; 4 Chesapeake Bay retrievers; 2 American cocker spaniels; 4 Glen of Imaal terriers; 2 Basenjis; 3 Poodles.