Abstract

The myoplasmic free [Ca2+] transient elicited by an action potential (Δ[Ca2+]) was compared in fast-twitch fibres of mdx (dystrophin null) and normal mice. Methods were used that maximized the likelihood that any detected differences apply in vivo. Small bundles of fibres were manually dissected from extensor digitorum longus muscles of 7- to 14-week-old mice. One fibre within a bundle was microinjected with furaptra, a low-affinity rapidly responding fluorescent calcium indicator. A fibre was accepted for study if it gave a stable, all-or-nothing fluorescence response to an external shock. In 18 normal fibres, the peak amplitude and the full-duration at half-maximum (FDHM) of Δ[Ca2+] were 18.4 ± 0.5 μm and 4.9 ± 0.2 ms, respectively (mean ±s.e.m.; 16°C). In 13 mdx fibres, the corresponding values were 14.5 ± 0.6 μm and 4.7 ± 0.2 ms. The difference in amplitude is statistically highly significant (P= 0.0001; two-tailed t test), whereas the difference in FDHM is not (P= 0.3). A multi-compartment computer model was used to estimate the amplitude and time course of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) calcium release flux underlying Δ[Ca2+]. Estimates were made based on several differing assumptions: (i) that the resting myoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]R) and the total concentration of parvalbumin ([ParvT]) are the same in mdx and normal fibres, (ii) that [Ca2+]R is larger in mdx fibres, (iii) that [ParvT] is smaller in mdx fibres, and (iv) that [Ca2+]R is larger and [ParvT] is smaller in mdx fibres. According to the simulations, the 21% smaller amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] in mdx fibres in combination with the unchanged FDHM of Δ[Ca2+] is consistent with mdx fibres having a ∼25% smaller flux amplitude, a 6–23% larger FDHM of the flux, and a 9–20% smaller total amount of released Ca2+ than normal fibres. The changes in flux are probably due to a change in the gating of the SR Ca2+-release channels and/or in their single channel flux. The link between these changes and the absence of dystrophin remains to be elucidated.

Dystrophin is a cytoskeletal protein that links actin filaments to proteins in the plasmalemma. In Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), loss of dystrophin leads to injury and death of skeletal muscle cells. Fast glycolytic fibres (type IIb) show a greater susceptibility to damage than oxidative fibres, at least in the initial stages of DMD (Webster et al. 1988; Minetti et al. 1991). The primary patho-physiological defect that leads to muscle cell damage is still unresolved, but a widely held view is that dystrophin and its associated proteins protect the fragile plasmalemma from the mechanical stresses that accompany contractile activity (McArdle et al. 1995). One long-standing hypothesis (reviewed by Gillis, 1999) is that loss of dystrophin leads to increased Ca2+ influx and abnormalities in the myoplasmic free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]), and that these abnormalities contribute to the injury and death of muscle cells.

The mdx mouse, which lacks dystrophin, is a widely used animal model of DMD. Both the resting myoplasmic free [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]R) and electrically evoked changes in [Ca2+] (Δ[Ca2+]) have been compared in fast-twitch fibres of mdx and normal mice, but there are significant qualitative and quantitative disagreements between different studies. [Ca2+]R in mdx fibres has been reported to be normal (Gailly et al. 1993; Head, 1993; Pressmar et al. 1994; Collet et al. 1999; Han et al. 2006) and 25–140% above normal (Turner et al. 1988, T1991; Hopf et al. 1996; Tutdibi et al. 1999). In addition, in mdx mice > 35 weeks of age, [Ca2+]R is reported to be 75% below normal (Collet et al. 1999). The amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] evoked by an action potential (AP) has been reported to be normal (Turner et al. 1988, 1991; Tutdibi et al. 1999; see also Head, 1993) and about half normal (Woods et al. 2004). The decay time course of the AP-evoked Δ[Ca2+] has been reported to be normal (Head, 1993), somewhat longer than normal (Turner et al. 1988, 1991; Tutdibi et al. 1999; see also Collet et al. 1999), and markedly longer than normal (Woods et al. 2004). Experimental differences that may contribute to these variable findings include the age of the mice, the muscle chosen for experimentation, the method of fibre preparation, the Ca2+ indicator used for the measurements, and the method of introducing the indicator into the myoplasm.

Here we compare measurements of Δ[Ca2+] elicited by an AP in fast-twitch fibres of extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles of 7- to 14-week-old mdx and normal mice. Our study employed methods that maximize the likelihood that any detected differences apply in vivo. These methods included use of: (1) freshly dissected bundles of intact fibres (i.e. fibres that are not enzyme-dissociated, dialysed, cut, permeabilized, cultured, or otherwise substantially modified); (2) the Ca2+ indicator furaptra (Raju et al. 1989), which is a low-affinity, rapidly responding indicator that appears to report accurately the properties of the large and brief Δ[Ca2+] evoked by an AP in skeletal muscle (Hirota et al. 1989; Konishi et al. 1991; Hollingworth et al. 1996); and (3) microinjection (rather than acetoxymethyl ester (AM)-loading) of furaptra into the fibres, which increases the accuracy of Δ[Ca2+] measurements (Zhao et al. 1997).

A major goal of our study was to see if we could confirm the large reduction in amplitude and large prolongation in time course of Δ[Ca2+] in mdx fibres that was recently reported by Woods et al. (2004), who were the first to study Δ[Ca2+] in mdx fibres with a low-affinity Ca2+ indicator. Our results indicate that mdx fibres have substantially smaller changes in Δ[Ca2+] than reported by Woods et al. (2004). We find that the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] elicited by an AP is, on average, 21% smaller in mdx than normal fibres while the time course of Δ[Ca2+] is essentially the same in mdx and normal fibres.

We have also used a computational model to estimate the changes in SR Ca2+ release flux that are required to explain the changes in Δ[Ca2+] that we have measured. The results indicate that, in comparison with normal fibres, mdx fibres have, on average, a ∼25% smaller peak flux, a 6–23% larger FDHM of the flux, and a 9–20% smaller total amount of released Ca2+.

A preliminary version of the results has appeared in abstract form (Baylor et al. 2008).

Methods

Animals

The mdx mice were from the C57BL/10ScSn strain lacking dystrophin. The normal mice were from two different strains: C57BL/10 mice, which have the same genetic background as the mdx mice, and Balb-C mice. As described in Results, no significant differences were observed between the measurements in the two normal strains. The mdx and C57BL/10 mice were a gift of Drs H. L. Sweeney and T. S. Khurana of the University of Pennsylvania. The Balb-C mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA).

Experimental procedures

Results were collected from experiments on 12 mdx mice, 4 C57BL/10 mice, and 8 Balb-C mice, aged 7–14 weeks. Animals were killed by rapid cervical dislocation following methods approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania. The EDL muscles were removed and bathed in an oxygenated Ringer solution containing (in mm): 150 NaCl, 2 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 Hepes (pH 7.4). A small bundle of fibres from the most distal head of the EDL muscle was isolated by manual dissection; a group of fibres on the outside edge of the bundle was left undisturbed during dissection (Hollingworth et al. 1996). The bundle was transferred to a Ringer-filled chamber (16°C) on an optical bench apparatus, and the tendon ends were attached to adjustable hooks. To minimize movement artifacts in the optical records, the bundle was passively stretched until the average sarcomere length of the fibres was ∼3.6 μm. In a few experiments, the Ringer solution also contained 5 μm BTS (N-benzyl-p-toluene sulphonamide) to further reduce fibre movement (Cheung et al. 2002). One fibre on the undisturbed side of the bundle was impaled with a micropipette containing 15 mm of the permanently charged form of furaptra (K4Mag-fura-2; Invitrogen, Inc.), which was carefully pressure-injected into the fibre. Indicator fluorescence at rest (FR) and in response to electrical stimulation (ΔF) was recorded from the full fibre width and a ∼300 μm length near the injection site (furaptra concentration, ∼0.1 mm). The methods for making these spatially averaged measurements have been described (Baylor & Hollingworth, 1988; Konishi et al. 1991; Hollingworth et al. 1996). In most experiments, the fluorescence excitation and emission wavelengths were 410 ± 20 nm and > 470 nm, respectively. The results are reported in normalized units, ΔF/FR. A fibre was accepted for study if it gave a stable, all-or-nothing ΔF/FR response to an action potential elicited by a brief external shock from a pair of electrodes positioned locally near the injection site.

Fluorescence calibrations

ΔfCaD, the spatially averaged change in the fraction of furaptra in the Ca2+-bound form, was calculated from ΔF/FR. With 410 nm excitation, ΔfCaD and ΔF/FR are related by the equation:

| (1) |

(Hollingworth et al. 1996; Baylor & Hollingworth, 2003).

Spatially averaged Δ[Ca2+] was estimated from ΔfCaD with the steady-state relation:

| (2) |

(Konishi et al. 1991). KD, furaptra's apparent dissociation constant for Ca2+ in the myoplasm, is assumed to be 96 μm (Baylor & Hollingworth, 2003).

Equation (2) assumes that the binding reaction between furaptra and Ca2+ is 1: 1, kinetically rapid, and of low affinity. As discussed previously, Δ[Ca2+] measured with furaptra is expected to be in approximate agreement with this assumption (Konishi et al. 1991). Some error, however, is expected because local elevations in [Ca2+] will be higher near the sites of SR Ca2+-release sites than away from these sites; thus, different regions of the sarcomere will contribute differing non-linearities to the relation between Δ[Ca2+] and ΔF/FR (Baylor & Hollingworth, 2007). The error due to this effect is minimized by use of a low-affinity indicator (Hirota et al. 1989; Baylor & Hollingworth, 1998). In simulations of mouse fast-twitch fibres activated by an AP, the estimated error in the amplitude of the furaptra Ca2+ transient calculated with eqn (2) is < 10% (Baylor & Hollingworth, 2007).

Estimation of SR Ca2+ release

The amplitude and time course of the SR Ca2+ release flux underlying Δ[Ca2+] were estimated with an 18-compartment model that permits simulation of myoplasmic Ca2+ movements within a half-sarcomere of one myofibril (Baylor & Hollingworth, 2007; cf. Cannell & Allen, 1984). The SR Ca2+ release flux enters the compartment in the model that is at the periphery of the half-sarcomere and offset ∼0.5 μm from the z-line, which is the approximate location of the triadic junctions in mammalian fibres (Smith, 1966; Eisenberg, 1983; Brown et al. 1998). The resultant changes in free and bound [Ca2+] in the various compartments are then calculated from: (i) [Ca2+]R, (ii) the rate at which Ca2+ enters the myoplasm through the SR Ca2+ release channels, (iii) the complexation reactions between Ca2+ and the major myoplasmic Ca2+ buffers (ATP, troponin, parvalbumin, the SR Ca2+ pump, and furaptra), (iv) the myoplasmic diffusion of free Ca2+ and the mobile Ca2+ buffers (ATP, parvalbumin, and furaptra), and (v) the rate at which Ca2+ is removed from myoplasm by the SR Ca2+ pump. The changes in Ca2+ binding and pumping in each compartment and the diffusion of Ca2+ and of the mobile Ca2+ buffers between compartments are calculated with an appropriate set of first-order differential equations. The parameters of the model for the standard simulation conditions are given in Tables 1–3 of Baylor & Hollingworth (2007). For the mdx simulations, no change was made in the complexation reaction between Ca2+ and the troponin regulatory sites, as tension–pCa measurements in skinned fibres of EDL muscle indicate that the apparent sensitivity of the contractile proteins to Ca2+ is not significantly different in mdx and normal fibres (22–25°C, 17- to 23-week-old mice, Williams et al. 1993; 22°C, 11-week-old mice, Divet & Huchet-Cadiou, 2002). Some reports in the literature, however, indicate that [Ca2+]R is higher, and the concentration of parvalbumin is lower, in mdx fibres than in normal fibres (see Results). Simulations for mdx fibres were therefore carried out with both normal and elevated values of [Ca2+]R and with both normal and reduced values of the concentration of parvalbumin.

To compare the simulations with the measurements, furaptra's simulated spatially averaged ΔfCaD waveform was calculated from the ΔfCaD waveforms in the 18 compartments (Baylor & Hollingworth, 2007). Equation (2) was then used to calculate the simulated spatially averaged Δ[Ca2+] waveform from the spatially averaged ΔfCaD. The SR Ca2+ release flux was calculated with an empirical function:

for t≥T. τ1 was set to 1.3 ms, and T (the delay between the stimulus pulse and the onset of Ca2+ release) was set to 1.4 ms. R and τ2 were adjusted iteratively until good agreement was observed between the peak and FDHM of the simulated Δ[Ca2+] waveform and the corresponding mean values in the measurements. τ2 fell in the range 0.5–0.7 ms, which yielded FDHM values of the release flux of 1.6–1.9 ms.

Statistics

Student's two-tailed t test was used to test for differences between mean values; the significance level was set at P < 0.05. The parameters tested included the four properties of Δ[Ca2+] listed in Table 1 and the vertical location of the data points relative to the simulated curve in Fig. 4A. For the latter test, points above the curve were assigned the value +1 and those below the curve were assigned −1.

Table 1.

Parameters of Δ[Ca2+] elicited by an action potential in intact EDL fibres (16°C)

| Peak amplitude | Time of half-rise | Time of peak | FDHM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (μm) | (ms) | (ms) | (ms) | |

| A. Normal fibres | ||||

| 1. Balb-C mice (n= 13) | 18.4 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.2 |

| 2. C57BL/10 mice (n= 5) | 18.5 ± 1.8 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.4 |

| 3. 1 and 2 combined (n= 18) | 18.4 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.2 |

| B. mdx fibres (n= 13) | 14.5 ± 0.6* | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.2 |

Entries are mean ±s.e.m. values of Δ[Ca2+] measured in a total of 31 experiments like those in Fig. 1. None of the parameter values is statistically significantly different between the two strains of normal mice (P > 0.05; see also open symbols in Fig. 4). * indicates that the difference in peak amplitudes between mdx fibres and all normal fibres (row 3) is statistically significant (P= 0.0001); for the other 3 parameters, differences between mdx and normal fibres are not significant (P > 0.05). The average sarcomere length in the experiments was 3.7 ± 0.1 μm in normal fibres and 3.5 ± 0.1 μm in mdx fibres. Some results from the Balb-C mice were reported previously (Hollingworth et al. 1996).

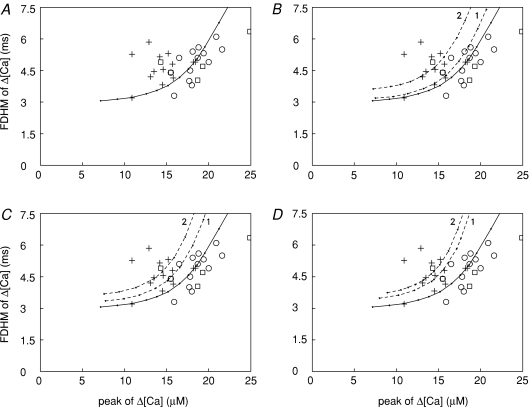

Figure 4. Relations between the FDHM and peak of Δ[Ca2+] elicited by an AP.

A, + represent mdx fibres and open symbols represent normal fibres (squares, C57BL/10 mice; circles, Balb-C mice). The continuous curve was obtained in simulations with the standard parameter values of the multi-compartment model; the amplitude of the SR Ca2+ release flux was varied incrementally while the FDHM of the flux was fixed at 1.57 ms (the value used for the normal fibre simulation in Table 2). The symbols and curve are also shown in B–D. B, the dashed curve labelled ‘1’ was obtained in the same way as the continuous curve except that [Ca2+]R was 100 (rather than 50) nm. Dashed curve ‘2’ was obtained with the same conditions as for curve ‘1’ except that the FDHM of the release flux was 1.81 ms (as in row B2 in Table 2) rather than 1.57 ms. C and D, dashed curves labelled ‘1’ were obtained as in B except that, in C, [ParvT] was 900 (rather than 1500) μm and, in D, [Ca2+]R was 100 nm and [ParvT] was 900 μm. Dashed curves ‘2’ were obtained with the same conditions as for curves ‘1’ except the FDHM of the release flux was 1.75 ms in C and 1.67 ms in D (as in rows B3 and B4, respectively, in Table 2).

Results

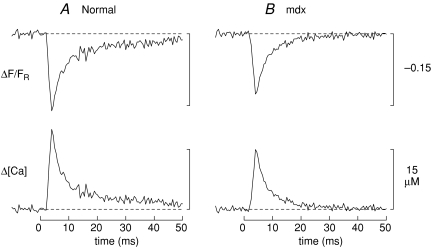

Figure 1 shows results from two representative experiments in which a fibre injected with furaptra was stimulated by an AP (panel A, normal fibre; panel B, mdx fibre). In each panel, the upper trace shows ΔF/FR and the lower trace shows spatially averaged Δ[Ca2+], which was calculated from ΔF/FR with eqns (1) and (2). The peak of Δ[Ca2+] is smaller in the mdx fibre than in the normal fibre (14.5 versus 18.7 μm), whereas the time of half-rise (3.1 versus 2.9 ms), time of peak (4.0 versus 4.0 ms), and FDHM (4.0 versus 4.0 ms) of Δ[Ca2+] are essentially identical in the two fibres.

Figure 1. Spatially averaged Ca2+ transients elicited by an AP in EDL fibres from C57BL/10 mice.

A, normal fibre; B, mdx fibre. In each panel, the upper trace shows the furaptra ΔF/FR response elicited by a supra-threshold external shock initiated at 0 time. The fluorescence excitation and emission wavelengths were 410 ± 20 nm and > 470 nm, respectively; FR was corrected for a small non-furaptra-related component of intensity. Six individual responses were averaged in A and four in B; the waiting time between successive shocks was 3 min. In A, the Ringer soultion contained 5 μm BTS; thus, this trace is likely to be virtually free of movement artifacts. In B, BTS was not used; thus this trace may be contaminated with a small movement artifact beginning 10–15 ms after stimulation. The lower panels show Δ[Ca2+] calculated from ΔF/FR with eqns (1) and (2). Fibre diameters, 42 μm and 39 μm; sarcomere length, 3.8 μm and 3.5 μm; furaptra concentration, 30 and 85 μm.

Table 1 lists the average properties of Δ[Ca2+] measured in 18 normal fibres and 13 mdx fibres. Results in normal fibres showed no significant differences according to strain (Balb-C versus C57BL/10; rows 1 and 2 of Table 1). Peak Δ[Ca2+] in the mdx fibres is, however, 21% smaller than that in the normal fibres (14.5 versus 18.4 μm, respectively; rows 3 and 4 of Table 1), a difference that is statistically highly significant (P= 0.0001). In contrast, none of the temporal parameters of Δ[Ca2+]– time of half-rise, time of peak, and FDHM – are statistically different in mdx and normal fibres (P > 0.05).

SR Ca2+ release estimated with the standard parameter values of the model

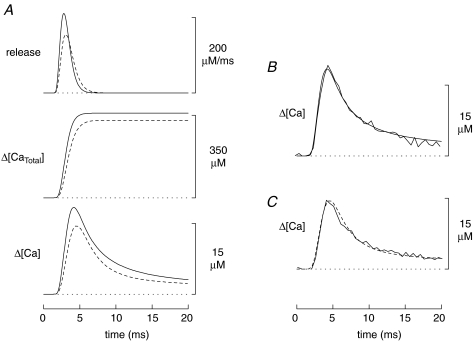

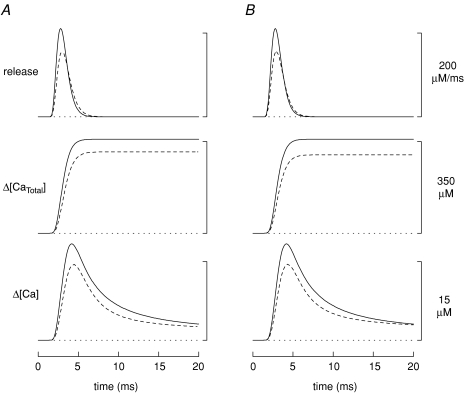

If [Ca2+]R and the concentrations of the myoplasmic Ca2+ buffers are similar in mdx and normal fibres, the most likely explanation of the smaller amplitude Ca2+ transient in mdx fibres is a reduction in the underlying SR Ca2+ release flux. To quantify this reduction, simulations were carried out with the 18-compartment model using the standard values of the model parameters (Baylor & Hollingworth, 2007). As described in Methods, in each simulation the amplitude and FDHM of the release flux were adjusted so that the peak and FDHM of the simulated Δ[Ca2+] waveform matched the corresponding values in Table 1. Figure 2A shows the results of these simulations (continuous traces, normal; dashed traces, mdx). The SR Ca2+ release flux (upper pair of traces) has a peak amplitude that is 26% smaller in the mdx simulation (156 versus 211 μm ms−1) and a FDHM that is 23% larger (1.93 versus 1.57 ms). The net effect of these differences on the change in the total concentration of released Ca2+ (Δ[CaTotal]; middle pair of traces) is a 9% reduction in the mdx simulation (328 versus 359 μm). The lower pair of traces shows the simulated spatially averaged Δ[Ca2+] waveforms. The results of these simulations are summarized as cases A and B1 in Table 2.

Figure 2.

A, comparison of model simulations for normal and mdx fibres (continuous and dashed traces, respectively). In both simulations, the standard parameter values of the model were used. The upper, middle and lower traces show, respectively, the SR Ca2+ release flux, the change in the total concentration of released Ca2+ (equal to the time integral of the flux), and the spatially averaged Δ[Ca2+] calculated with eqn (2) from the simulated ΔfCaD response of furaptra; the concentration units of all traces are referred to the myoplasmic water volume (Baylor et al. 1983). The peak and FDHM of the Δ[Ca2+] traces match the corresponding mean values in the last two rows of Table 1. B, comparison of simulated and measured Δ[Ca2+] waveforms in normal fibres. The simulated waveform (noise-free trace) is identical to the lowermost continuous trace in A; the measured waveform (noisy trace) is Δ[Ca2+] averaged from four normal fibres. C, same comparison as in B but for mdx fibres. The dashed waveform is identical to the lowermost dashed trace in A; the continuous waveform was averaged from four mdx fibres.

Table 2.

Estimation of SR Ca2+ release elicited by an action potential in intact EDL fibres (16°C)

| Peak release flux | FDHM of release flux | Δ[CaTotal] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (μm ms−1) | (ms) | (μm) | |

| A. Normal fibres | 211 | 1.57 | 359 |

| B. mdx fibres | |||

| 1. With standard model parameters | 156 (0.74) | 1.93 (1.23) | 328 (0.91) |

| 2. With [Ca2+]R increased 100% | 157 (0.74) | 1.81 (1.15) | 311 (0.87) |

| 3. With [ParvT] reduced 40% | 158 (0.75) | 1.75 (1.11) | 299 (0.83) |

| 4. With [Ca2+]R increased 100% and[ParvT] reduced 40% | 158 (0.75) | 1.67 (1.06) | 288 (0.80) |

Entries were obtained from simulations with the multi-compartment model described in Methods (cf. Figs 2 and 3); all concentrations are referred to the myoplasmic water volume. Results for normal fibres and for case 1 of mdx fibres used the standard parameter values of the model (Baylor & Hollingworth, 2007). Case 2 of mdx fibres used [Ca2+]R= 100 (rather than 50) nm, case 3 used [ParvT]= 900 (rather than 1500) μm, and case 4 used [Ca2+]R= 100 nm and [ParvT]= 900 μm. In all simulations, the amplitude and FDHM of the release flux were adjusted so that the amplitude and FDHM of the simulated Δ[Ca2+] matched the values in rows 3 and 4 of Table 1 (normal and mdx, respectively). In B, the numbers in parentheses give the ratio of the mdx value to the corresponding normal value.

The Δ[Ca2+] traces in Fig. 2A are also shown in panels B and C of Fig. 2 (noise-free traces; normal and mdx, respectively). These traces are also compared with experimental measurements of Δ[Ca2+], which were averaged from four normal fibres (Fig. 2B) and from four mdx fibres (Fig. 2C); these fibres were selected because their ΔF/FR recordings appeared to have little or no contamination with movement artifacts. The good agreement between the simulated and measured traces in Fig. 2B and C supports the conclusion that the multi-compartment model provides a good description of the intracellular Ca2+ movements that underlie the Δ[Ca2+] measurements.

Estimation of SR Ca2+ release if [Ca2+]R is elevated in mdx fibres

Contrary to the assumption in the simulations of Fig. 2A, it is possible that myoplasmic properties differ in mdx and normal fibres. For example, some studies have reported that [Ca2+]R is elevated by 25–140% in mdx fibres (Turner et al. 1988, 1991; Hopf et al. 1996; Tutdibi et al. 1999). To examine this possibility, simulations for mdx fibres were carried out with [Ca2+]R increased by 100%, from its standard value of 50 nm (as in Fig. 2) to 100 nm. The dashed traces in Fig. 3A show the result. In this case, the peak of the Ca2+ release flux in the mdx simulation is 26% smaller than normal (157 versus 211 μm ms−1), the FDHM of the release flux is 15% larger (1.81 versus 1.57 ms), and Δ[CaTotal] is 13% smaller (311 versus 359 μm) (case B2 in Table 2).

Figure 3.

Same comparisons as those in Fig. 2A except that, in the mdx simulation, [Ca2+]R is assumed to be 100 (rather than 50) nm (A) or [ParvT] is assumed to be 900 (rather than 1500) μm (B).

Estimation of SR Ca2+ release if [ParvT] is reduced in mdx fibres

Sano et al. (1990) reported that, in tibialis anterior muscle (a predominantly fast-twitch muscle), the parvalbumin concentration of 7- to 14-week-old mice is ∼40% smaller in mdx fibres than in normal fibres. To examine this possibility, simulations for mdx fibres were carried out with [ParvT] (the concentration of the parvalbumin Ca2+/Mg2+ sites in the model) reduced by 40%, from 1500 to 900 μm. The dashed traces in Fig. 3B show the result. In this case, the peak of the SR Ca2+ release flux is 25% smaller in the mdx simulation (158 versus 211 μm ms−1), the FDHM of the flux is 11% larger (1.75 versus 1.57 ms), and Δ[CaTotal] is 17% smaller (299 versus 359 μm) (case B3 in Table 2).

Estimations of SR Ca2+ release if there is both elevation of [Ca2+]R and reduction of [ParvT] in mdx fibres

Simulations for mdx fibres were also carried out with [Ca2+]R= 100 nm and [ParvT]= 900 μm, i.e. the combination of the two previous cases (traces not shown). In this case, the peak of the SR Ca2+ release flux is 25% smaller in the mdx simulation (158 versus 211 μm ms−1), the FDHM of the flux is 6% larger (1.67 versus 1.57 ms), and Δ[CaTotal] is 20% smaller (288 versus 359 μm) (case B4 in Table 2).

Relations between the amplitude and FDHM of Δ[Ca2+]

Previous work indicates that, in normal EDL fibres, a positive correlation exists between the FDHM and peak amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] (Baylor & Hollingworth, 2007). Figure 4 explores this correlation for both normal and mdx fibres. Figure 4A shows the FDHM of Δ[Ca2+] plotted versus the peak of Δ[Ca2+] for the 31 fibres used for this study (open symbols, normal fibres; +, mdx fibres). The data for the normal fibres appear to be positively correlated. As shown by the continuous curve in Fig. 4A, such a correlation is expected if the FDHM of the SR release flux is constant and the amplitude of the release flux varies somewhat among otherwise identical fibres. The mdx data do not reveal a positive correlation, possibly due to the smaller size of this data set. Interestingly, the relation between amplitude and FDHM in the mdx data differs statistically from that in the normal data (P= 0.003), as most of the mdx data points lie above the curve in Fig. 4A, whereas a majority of the normal data points lie below the curve.

The dashed curves in Fig. 4B–D explore the idea that the upward shift in the mdx data in Fig. 4A is a consequence of an increase in [Ca2+]R and/or a reduction in [ParvT]. Results are shown, respectively, for the cases considered earlier, namely, that (i) [Ca2+]R is increased, (ii) [ParvT] is reduced, or (iii) both [Ca2+]R is increased and [ParvT] is reduced. In each panel, the relation between amplitude and FDHM of Δ[Ca2+] in mdx fibres was simulated in two ways: either the FDHM of the release flux was kept the same as that used for the continuous curve (dashed curve ‘1’) or the FDHM of the release flux was set to the value in Table 2 for the corresponding case (dashed curve ‘2’; cf. Figs 2 and 3). In all cases, the dashed curves are shifted upward with respect to the continuous curve and provide a better fit to the mdx data than the continuous curve. Thus, the upward shift in the mdx data relative to the normal data in Fig. 4 is consistent with the idea that mdx fibres have an increase in [Ca2+]R, a reduction in [ParvT], or both.

Estimation of Ca2+ binding to troponin

Model estimates of Ca2+ binding to the troponin regulatory sites (two per troponin molecule) were also obtained in the simulations. The complexation reaction between Ca2+ and the regulatory sites is assumed to be a two-step reaction with positive cooperativity (Hollingworth et al. 2006); the free [Ca2+] at which 50% of the sites are occupied with Ca2+ in the steady state is 1.3 μm. In the normal fibre simulation, 0.9% of the troponin sites are occupied with Ca2+ at rest and, in response to an AP, the (spatially averaged) peak occupancy reaches 96.3%. In the mdx simulations, the resting occupancy is 0.9 and 2.3% ([Ca2+]R= 50 and 100 nm, respectively) and the peak occupancy varies between 90.9 and 92.0% for the four cases summarized in part B of Table 2. Thus, in the mdx simulations, the Ca2+-troponin occupancy is reduced only slightly (∼5%) as a result of the 21% reduction in the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+]. This small reduction in Ca2+-troponin occupancy might account for part of the reduction in twitch-specific force that is reported for EDL muscle in young adult mdx mice: ∼10% in 6- to 8-week-old mice (whole muscles at 22–24°C, Chan et al. 2007) and 33% in 12-week-old mice (small fibre bundles at 19–22°C, Louboutin et al. 1995). On the other hand, a more important factor underlying the reduction in twitch-specific force may reside in the force-generating capability of the myofilaments, as tension–pCa measurements on small bundles of chemically skinned EDL fibres indicate that specific force at saturating [Ca2+] is reduced by ∼35% in mdx fibres (bundles of 2–5 fibres from 11-week-old mice, 22°C; Divet & Huchet-Cadiou, 2002; see also Williams et al. 1993; who reported a ∼20% reduction at 22–25°C in chemically skinned single EDL fibres from 17- to 23-week-old mice, a difference that was not statistically significant).

Discussion

This article compares Δ[Ca2+] elicited by an AP in intact skeletal muscle fibres of mdx and normal mice. Measurements were made in fibres injected with the permanently charged form of furaptra, a low-affinity, rapidly responding Ca2+ indicator. The preparation and methodology were chosen to maximize the accuracy of the measurements and the likelihood that the results apply in vivo.

The measurements show an average reduction of ∼20% in the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] in mdx compared to normal fibres. In contrast, the time of half-rise, time of peak, and FDHM of Δ[Ca2+] are unchanged in mdx fibres (Table 1). It should be noted that the later falling phase of the furaptra ΔF signal (e.g. for time > 15 ms after stimulation; cf. Fig. 1) includes a small component caused by a change in myoplasmic free [Mg2+] (Konishi et al. 1991) and, in some experiments, is also contaminated with a movement artifact; thus our measurements do not rule out the possibility that the late falling phase of Δ[Ca2+] might differ somewhat in mdx and normal fibres.

Comparisons with previous Δ[Ca2+] measurements in mdx and normal fibres

Our findings of relatively small differences in Δ[Ca2+] elicited by an AP in mdx and normal fibres differ substantially from those of Woods et al. (2004), who compared Δ[Ca2+] in enzyme-dissociated fibres using the permanently charged form of the low-affinity Ca2+ indicator Oregon Green 488 Bapta-5N (OGB-5N). These authors studied fibres from 8- to 18-week-old mice at a sarcomere length of ∼2 μm (22°C). Movements artifacts at the short sarcomere length were eliminated either by the introduction of 5 mm EGTA into the myoplasm or by the use of 50 μm BTS. The EGTA experiments, which were carried out in fibres dissociated from both EDL and flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles, are not directly comparable to ours because 5 mm EGTA modifies Δ[Ca2+], reducing its amplitude and abbreviating its time course to approximately that of the SR Ca2+ release flux (Song et al. 1998; Woods et al. 2004). The experiments using BTS to reduce movement, which are more comparable to ours, were carried out on fibres dissociated from FDB muscles. In these fibres Woods et al. reported that the peak amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] is reduced by ∼45%, from 6.0 ± 0.1 μm in normal fibres to 3.3 ± 0.2 μm in mdx fibres. This reduction in amplitude in mdx fibres is more than twice the reduction found by us (21%; Table 1), a difference that appears to be statistically highly significant as judged from the s.e.m.s of amplitude reductions in the two studies (± 3% if expressed as a percentage of the mean amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] in normal fibres). Woods et al. also reported that the FDHM of Δ[Ca2+] is increased 6-fold in fibres not containing EGTA, from 8 ms in normal fibres to 48 ms in mdx fibres. Their value of 48 ms for the FDHM at 22°C stands in marked contrast to our finding that the FDHM in mdx fibres is ∼5 ms at 16°C and unchanged from that in normal fibres. In their EGTA experiments, Woods et al. (2004) also found that mdx fibres have a large reduction in the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] elicited by an AP: by 46% in FDB fibres and by 54% in EDL fibres. As expected, the FDHM of Δ[Ca2+] in these EGTA experiments was brief in all cases, 2–4 ms, due to the Ca2+-buffering action of EGTA.

The reason(s) for the difference between our results on EDL fibres and those of Woods et al. (2004) on FDB fibres not containing EGTA is unclear. There is no reason to expect that the properties of Δ[Ca2+] would differ substantially between fast-twitch fibres of EDL and FDB muscles. In agreement with this expectation, in the EGTA experiments of Woods et al. (2004), the properties of Δ[Ca2+] differed in minor ways only between EDL and FDB fibres from either normal or mdx muscles. Thus, it seems unlikely that the differences between our study and that of Woods et al. are due to the different muscles employed.

Other experimental differences between our study and that of Woods et al. (2004) include the choice of Ca2+ indicator (furaptra versus OGB-5N, respectively), the method of fibre preparation (intact versus enzymatically dissociated), the sarcomere length of the fibres (∼3.6 versus∼2.0 μm), and the method of introducing the indicator into the fibre (pressure injection versus passive loading from a low-resistance micropipette in the case of their FDB fibres or passive diffusion from a cut end in the case of their EDL fibres). The fact that different Ca2+ indicators were used in the two studies could be significant. OGB-5N is a visible wavelength tetracarboxylate Ca2+ indicator of relatively large molecular weight (920 Da for the hexavalent anion); in contrast, furaptra is a shorter wavelength tricarboxylate indicator of smaller molecular weight (430 Da for the tetravalent anion). In general, larger visible wavelength indicators (e.g. calcium orange, calcium-orange-5N, calcium-green-5N, and BTC) bind more heavily to myoplasmic constituents than does furaptra and track the kinetics of Δ[Ca2+] less reliably (Zhao et al. 1996, 1997). In addition, some visible wavelength indicators reveal a prominent slow component that is not directly related to Ca2+ complexation (Zhao et al. 1996; see also Baylor et al. 1982). Thus, it would not be surprising if OGB-5N tracks Δ[Ca2+] less reliably than furaptra.

Our use of stretched fibres and pressure injection of indicator is also potentially significant, as the absence of dystrophin may increase the fragility of the surface membrane (reviewed in McArdle et al. 1995), which could make mdx fibres more susceptible to damage by stretch and/or pressure injection. We cannot rule out the possibility that an effect of this kind could contribute to the reduction in the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] that we have measured in mdx fibres (Table 1). However, the changes in Δ[Ca2+] in mdx fibres found by Woods et al. (2004) are much larger than those found by us; thus, the differences between the two studies cannot be attributed to selective membrane damage of our mdx fibres by stretch or pressure injection

The isolation of fibres by enzymatic dissociation is clearly more perturbing than isolation of a bundle of intact fibres by careful manual dissection. As noted by Woods et al. (2004), immediately following their enzyme dissociations, only a small percentage of fibres actively twitched in response to electrical stimulation; this percentage increased to ∼25% after a 30 min incubation in an O2-saturated L-15 media (Sigma) containing antibiotics. Although Woods et al. experimented only on fibres capable of giving a vigorous twitch, it nevertheless seems possible that the enzyme digestion perturbed the properties of these fibres and produced the large differences between the mdx and normal fibres. Against this possibility, however, are results from three other studies in which enzyme digestion was used yet relatively small differences between Δ[Ca2+] in mdx and normal fibres were found. These studies used a high-affinity slowly responding tetra-carboxylate Ca2+ indicator – either fura-2 (Head, 1993; Tutdibi et al. 1999) or indo-1 (Collet et al. 1999); because of this, the ability to accurately distinguish changes in the amplitude and the time course of Δ[Ca2+] was compromised. Head (1993) found that, in mdx fibres, the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] elicited by an AP fell within the same 3-fold range found in normal fibres and had the same variability; in addition, the kinetics of Δ[Ca2+] was indistinguishable in mdx and normal fibres out to ∼500 ms after stimulation (22°C). Tutdibi et al. (1999), who stimulated fibres repetitively (1 Hz, 20–24°C) rather than with a single AP, found no difference in the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] in mdx and normal fibres; in contrast, they reported that the decay time constant of Δ[Ca2+] in mdx fibres, while within the same range as that found for normal fibres (10–55 ms), was, on average, somewhat larger (50% of mdx fibres had time constants > 35 ms compared with 20% of normal fibres). In the experiments of Collet et al. (1999), who used the voltage-clamp technique to elicit Δ[Ca2+] with depolarizations from −80 to 0 mV for periods of 5–50 ms (20–22°C), the most notable differences were that mdx fibres had a ∼2-fold larger time constant of decay of Δ[Ca2+] in response to a 5 ms depolarization and a somewhat larger peak Δ[Ca2+] and final level of Δ[Ca2+] in response to a 15 ms depolarization. Relatively small differences between Δ[Ca2+] in mdx and normal fibres were also found by Turner et al. (1988, 1991), who used intact (rather than enzymatically dissociated) FDB fibres that were AM-loaded with fura-2 and activated by repetitive stimulation (25 and 37°C). These authors found no difference in the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] in mdx fibres, although they did find an increase in the time to peak of 15–30% and an increase in the decay time constant of 40–60%. Overall, none of these studies that used a high-affinity Ca2+ indicator detected a significant reduction in the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] in mdx fibres. In contrast, Woods et al. (2004), who used the high-affinity indicator OGB-1 in some experiments, found that the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] was 36% smaller in mdx fibres than in normal fibres, which is slightly smaller than the reductions that they found with OGB-5N (45, 46 and 54%, depending on experimental conditions; see above). On balance, the large differences found by Woods et al. (2004) in comparison with these other studies and our own suggest that these large differences do not apply to fibres in their normal physiological state. A factor unique to the experiments of Woods et al. (2004) is that the myoplasm of their fibres was dialysed with an artificial internal solution (primarily, potassium aspartate) for a period of 30 min prior to optical recording, with recording and dialysis usually continuing for another 30 min or more. This prolonged dialysis procedure might have produced some change in the physiological properties of their fibres (cf. Irving et al. 1987), including an increase in the FDHM of Δ[Ca2+] (Maylie et al. 1987).

A final factor that might have contributed to the larger values of the FDHM of Δ[Ca2+] in the fibres of Woods et al. (2004) that did not contain EGTA is the large concentration of BTS, 50 μm, that was used to reduce movement artifacts in the fluorescence measurements. This concentration of BTS prolongs the decay phase of the AP somewhat (Woods et al. 2004), which, in turn, would be expected to prolong the time course of SR Ca2+ release and of Δ[Ca2+]. In our experiments, we relied primarily on stretch to reduce movement artifacts, although 5 μm BTS was also used in a few experiments (e.g. Fig. 1A). In frog twitch fibres, 5 μm BTS does not alter Δ[Ca2+] and is not expected to alter the AP (Cheung et al. 2002).

In summary, we believe that the relatively small differences that we have detected between Δ[Ca2+] in mdx and normal EDL fibres probably represent the main changes that apply in vivo to fast-twitch fibres of 7- to 14-week-old mice. The exact reason for the much larger effects detected in the experiments of Woods et al. (2004) remains unclear.

Evidence that myoplasmic properties are different in mdx and normal fibres

In our experiments, the observed values of the FDHM of Δ[Ca2+] in mdx fibres are larger than expected based on the measured reductions in the peak amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] in mdx fibres and on the relation between the FDHM and peak of Δ[Ca2+] observed in normal fibres (Fig. 4A). The larger-than-expected FDHM values in mdx fibres are consistent with the idea that mdx fibres have an increase in [Ca2+]R (Turner et al. 1988,1991; Hopf et al. 1996; Tutdibi et al. 1999), a reduction in the concentration of parvalbumin (Sano et al. 1990), or both (Fig. 4B–D). The effect of an increase in [Ca2+]R is similar to that of a reduction in [ParvT] because the main effect of an increase in [Ca2+]R is to reduce the availability of metal-free sites on parvalbumin. These sites bind Ca2+ rapidly and contribute to the early decay of Δ[Ca2+] (Baylor & Hollingworth, 2007); consequently, a reduction in these sites leads to a larger FDHM of Δ[Ca2+] for a given amplitude of Δ[Ca2+].

In Fig. 4, there appears to be a greater scatter in the mdx data than in the normal data. A possible explanation for this effect is that mdx fibres have a greater percentage variation in [Ca2+]R and/or [ParvT] than normal fibres. Another factor that may possibly contribute is some minor damage in the mdx fibres due to our use of long sarcomere length and/or pressure injection of indicator (see above).

Differences between SR Ca2+ release in mdx and normal fibres

Our compartment modelling indicates that the properties of Δ[Ca2+] elicited by an AP in mdx fibres are consistent with these fibres having, on average, a ∼25% smaller peak SR Ca2+ release flux, a 6–23% larger FDHM of the flux, and a 9–20% smaller total amount of released Ca2+ than normal fibres (Table 2). Some increase in the FDHM of the release flux would be expected to accompany a reduction in the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+], as previous work indicates that Δ[Ca2+] feeds back rapidly in a negative fashion to inhibit release (Baylor et al. 1983; Schneider & Simon, 1988; Baylor & Hollingworth, 1988; Jong et al. 1995). Thus, if the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] is smaller, the effectiveness of the feedback inhibition should be reduced, and a prolongation of the time course of the release flux would be expected.

Woods et al. (2004,2005) also compared the peak rate of SR Ca2+ release in mdx and normal fibres. In contrast to our results, they estimated larger reductions in release in mdx fibres – by 46% in response to a single AP and by 67% in response to a voltage-clamp depolarization to 0 mV. These large reductions are related to the large reductions in the amplitude of Δ[Ca2+] measured with OGB-5N in their mdx fibres (Woods et al. 2004,2005; see also the second section of Discussion). As discussed above, the precise reason for the large effects detected by Woods et al. remains to be elucidated.

Possible mechanisms underlying a reduction in SR Ca2+ release in mdx fibres

Previous reports indicate that a number of key determinants of the excitation–contraction coupling process in skeletal muscle are similar in mdx and normal fibres, including the resting membrane potential (Hollingworth et al. 1990; Mathes et al. 1991), the action potential (Woods et al. 2004), the structure and electrical charging of the transverse tubules (Woods et al. 2005), and the amount and kinetics of voltage-dependent charge movement (Hollingworth et al. 1990; Collet et al. 2003). If these similarities also apply under the experimental conditions of our study, the most likely explanation for the reduction in SR Ca2+ release that we estimate occurs in mdx fibres is a change either in the gating of the SR Ca2+-release channels (ryanodine receptors, RyRs) or in their single channel Ca2+ flux. Possible contributing factors include alteration(s) in the myoplasmic constituents, the constituents within the lumen of the SR, and/or the proteins of the SR membrane, including the RyRs and the SR Ca2+ pump. Such alterations might be caused by a chronic elevation of [Ca2+]R (Turner et al. 1988,1991; Hopf et al. 1996; Tutdibi et al. 1999), which is often associated with a reduction in electrically evoked SR Ca2+ release (Lamb et al. 1995; Chin & Allen, 1996; Yeung et al. 2005). A chronic elevation of [Ca2+]R could result in increased activity of proteases such as calpains (e.g. Turner et al. 1988; Gillis, 1999; Gailly et al. 2007), which could alter the normal structural arrangement between the t-tubular and SR membranes (Verburg et al. 2005) and hence the physiological coupling between the t-tubular voltage sensors and the RyRs. An increase in [Ca2+]R could also compromise the metabolic state of the fibre (e.g. Dunn et al. 1991; Whitehead et al. 2006), which could inhibit gating of RyRs by altering the concentrations of key myoplasmic constituents such as ATP, ADP, Mg2+ and H+. In addition, mdx fibres are reported to have a reduction in the activity of the SR Ca2+ pump (Kometani et al. 1990; Kargacin & Kargacin, 1996; Divet & Huchet-Cadiou, 2002) and a reduction in Ca2+-binding proteins within the SR (Culligan et al. 2002; Dowling et al. 2004; Doran et al. 2004). This could result in a reduced SR Ca2+ load, a reduced driving force for Ca2+ release, and a reduced single channel Ca2+ flux.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Knox Chandler for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Muscular Dystrophy Association, the US National Institutes of Health (GM 86167, EY13862), and the Pennsylvania Department of Health. The Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions.

References

- Baylor SM, Chandler WK, Marshall MW. Dichroic components of arsenazo III and dichlorophosphonazo III signals in skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1982;331:179–210. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor SM, Chandler WK, Marshall MW. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release in frog skeletal muscle fibres estimated from arsenazo III calcium transients. J Physiol. 1983;344:625–666. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor SM, Hollingworth S. Fura-2 calcium transients in frog skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1988;403:151–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor SM, Hollingworth S. Model of sarcomeric Ca2+ movements, including ATP Ca2+ binding and diffusion, during activation of frog skeletal muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:297–316. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor SM, Hollingworth S. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release compared in slow-twitch and fast-twitch fibres of mouse muscle. J Physiol. 2003;551:125–138. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.041608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor SM, Hollingworth S. Simulation of Ca2+ movements within the sarcomere of fast-twitch mouse fibres stimulated by action potentials. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:283–302. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor SM, Zeiger U, Hollingworth S. Comparison of the spatially-averaged myoplasmic calcium transient (Δ[Ca]) elicited by an action potential (AP) in fast-twitch fibers of normal and mdx mice. Biophysical Society Meeting Abstract. Biophys J. 2008;94:308a. [Google Scholar]

- Brown IE, Kim DH, Loeb GE. The effect of sarcomere length on triad location in intact feline caudofemoralis muscle fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1998;19:473–477. doi: 10.1023/a:1005309107903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannell MB, Allen DG. Model of calcium movements during activation in the sarcomere of frog skeletal muscle. Biophys J. 1984;45:913–925. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84238-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S, Head SI, Morley JW. Branched fibres in dystrophic mdx muscle are associated with a loss of force following lengthening contractions. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;93:C985–C992. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00128.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung A, Dantzig JA, Hollingworth S, Baylor SM, Goldman YE, Mitchison TJ, Straight AF. A small-molecule inhibitor of skeletal muscle myosin II. Nature Cell Biol. 2002;4:83–88. doi: 10.1038/ncb734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin ER, Allen DG. The role of elevations in intracellular Ca2+ concentration in the development of low frequency fatigue in mouse single muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1996;491:813–824. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collet C, Allard B, Tourneur Y, Jacquemond V. Cellular calcium signals measured with indo-1 in isolated skeletal muscle fibres from control and mdx mice. J Physiol. 1999;520:417–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collet C, Csernoch L, Jacquemond V. Intramembrane charge movement and L-type calcium current in skeletal muscle fibres from control and mdx mice. Biophys J. 2003;84:251–265. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74846-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culligan K, Banville N, Dowling P, Ohlendieck K. Drastic reduction of calsequestrin-like proteins and impaired calcium binding in dystrophic mdx muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:435–445. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00903.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divet A, Huchet-Cadiou C. Sarcoplasmic reticulum function in slow- and fast-twitch skeletal muscles from mdx mice. Pflugers Arch. 2002;444:634–643. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran P, Dowling P, Lohan J, McDonnell K, Poetsch S, Ohlendieck K. Subproteomics analysis of Ca2+-binding proteins demonstrates decreased calsequestrin expression in dystrophic mouse skeletal muscle. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:3943–3952. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling P, Doran P, Ohlendieck K. Drastic reduction of sarcalumenin in Dp427 (dystrophin of 427 kDa)-deficient fibres indicates that abnormal calcium handling plays a key role in muscular dystrophy. Biochem J. 2004;379:479–488. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JF, Frostick S, Brown G, Radda GK. Energy status of cells lacking dystrophin: an in vivo/in vitro study of mdx mouse skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1096:115–120. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(91)90048-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg BR. Quantitative ultrastructure of mammalian skeletal muscle. In: Peachey LD, Adrian RH, Geiger SR, editors. Handbook of Physiology, section 10, Skeletal Muscle. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1983. pp. 73–112. [Google Scholar]

- Gailly P, Boland B, Himpens B, Casteels R, Gillis JM. Critical evaluation of cytosolic calcium determination in resting muscle fibres from normal and dystrophic (mdx) mice. Cell Calcium. 1993;14:473–483. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(93)90006-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gailly P, De Backer F, Van Schoor M, Gillis JM. In situ measurements of calpain activity in isolated muscle fibres from normal and dystrophin-lacking mdx mice. J Physiol. 2007;582:1261–1275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis JM. Understanding dystrophinopathies: an inventory of the structural and functional consequences of the absence of dystrophin in muscles of the mdx mouse. J Mus Res Cell Motility. 1999;20:605–625. doi: 10.1023/a:1005545325254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han R, Grounds MD, Bakker AJ. Measurement of sub-membrane [Ca2+] in adult myofibres and cytosolic [Ca2+] in myotubes from normal and mdx mice using the Ca2+ indicator FFP-18. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head SI. Membrane potential, resting calcium and calcium transients in isolated muscle fibres from normal and dystrophic mice. J Physiol. 1993;469:11–19. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota A, Chandler WK, Southwick PL, Waggoner AS. Calcium signals recorded from two new purpurate indicators inside frog cut twitch fibres. J Gen Physiol. 1989;94:597–631. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.4.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth S, Chandler WK, Baylor SM. Effects of tetracaine on calcium sparks in frog intact skeletal muscle fibres. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:291–307. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth S, Marshall MW, Robson E. Excitation contraction coupling in normal and mdx mice. Muscle Nerve. 1990;13:16–20. doi: 10.1002/mus.880130105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth S, Zhao M, Baylor SM. The amplitude and time course of the myoplasmic free [Ca2+] transient in fast-twitch fibres of mouse muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1996;108:455–469. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.5.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopf FW, Turner PR, Denetclaw WF, Reddy R, Steinhardt RA. A critical evaluation of resting intracellular free calcium regulation in dystrophic mdx muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1996;271:C1325–C1339. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.4.C1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving M, Maylie J, Sizto NL, Chandler WK. Intrinsic optical and passive electrical properties of cut frog twitch fibres. J Gen Physiol. 1987;89:1–40. doi: 10.1085/jgp.89.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong D-S, Pape PC, Baylor SM, Chandler WK. Calcium inactivation of calcium release in frog cut muscle fibres that contain millimolar EGTA or Fura-2. J Gen Physiol. 1995;106:337–388. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.2.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargacin ME, Kargacin GJ. The sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump is functionally altered in dystrophic muscles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1290:4–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(95)00180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kometani K, Tsugeno H, Yamada K. Mechanical and energetic properties of dystrophic (mdx) mouse muscle. Jap J Physiol. 1990;40:541–549. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.40.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi M, Hollingworth S, Harkins AB, Baylor SM. Myoplasmic calcium transients in intact frog skeletal muscle fibres monitored with the fluorescent indicator furaptra. J Gen Physiol. 1991;97:271–301. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb GD, Junankar PR, Stephenson DG. Raised intracellular [Ca2+] abolishes excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle fibres of rat and toad. J Physiol. 1995;489:349–362. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louboutin JP, Fichter-Gagnepain V, Pastoret C, Thaon E, Noireaud J, Sebille A, Fardeau M. Morphological and functional study of extensor digitorum longus muscle regeneration after iterative crush lesions in mdx mouse. Neuromuscul Disord. 1995;5:489–500. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(95)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle A, Edwards RHT, Jackson MJ. How does dystrophin deficiency lead to muscle degeneration?– Evidence from the mdx mouse. Neuromuscul Disord. 1995;5:445–456. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(95)00001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathes C, Bezanilla F, Weiss RE. Sodium current and membrane potential in EDL muscle fibres from normal and dystrophic (mdx) mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1991;261:C718–C725. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.4.C718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maylie J, Irving M, Sizto NL, Chandler WK. Comparison of arsenazo III optical signals in intact and cut frog twitch fibres. J Gen Physiol. 1987;89:41–81. doi: 10.1085/jgp.89.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minetti C, Ricci E, Bonilla E. Progressive depletion of fast alpha-actinin-positive muscle fibres in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 1991;41:1977–1981. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.12.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressmar J, Brinkmeier H, Seewald MJ, Naumann T, Rudel R. Intracellular Ca2+ concentrations are not elevated in resting cultured muscle from Duchenne (DMD) patients and in MDX mouse muscle fibres. Pflugers Arch. 1994;426:499–505. doi: 10.1007/BF00378527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju B, Murphy E, Levy LA, Hall RD, London RE. A fluorescent indicator for measuring cytosolic free magnesium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1989;256:C540–C548. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.3.C540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano M, Yokota T, Endo T, Tsukagoshi H. A developmental change in the content of parvalbumin in normal and dystrophic mouse (mdx) muscle. J Neurol Sci. 1990;97:261–272. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(90)90224-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MF, Simon BJ. Inactivation of calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in frog skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1988;405:727–745. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DS. The organization and function of the sarcoplasmic reticulum and T system of muscle cells. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1966;16:109–142. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(66)90004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L-S, Sham JSK, Stern MD, Lakatta EG, Cheng H. Direct measurement of SR release flux by tracking ‘Ca spikes’ in rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 1998;512:677–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.677bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner PR, Fong PY, Denetclaw WF, Steinhardt RA. Increased calcium influx in dystrophic muscle. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1701–1712. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.6.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner PR, Westwood T, Regen CM, Steinhardt RA. Increased protein degradation results from elevated free calcium levels found in muscle from mdx mice. Nature. 1988;335:735–738. doi: 10.1038/335735a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutdibi O, Brinkmeier H, Rudel R, Fohr KJ. Increased calcium entry into dystrophin-deficient muscle fibres of MDX and ADR-MDX mice is reduced by ion channel blockers. J Physiol. 1999;515:859–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.859ab.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verburg E, Murphy RM, Stephenson DG, Lamb GD. Disruption of excitation-contraction coupling and titin by endogenous Ca2+-activated proteases in toad muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2005;564:775–789. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.082180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster C, Silberstein L, Hays AP, Blau HM. Fast muscle fibres are preferentially affected in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1988;52:503–513. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90463-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead NP, Yeung EW, Allen DG. Muscle damage in mdx (dystrophic) mice: role of calcium and reactive oxygen species. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:657–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DA, Head SI, Lynch GS, Stephenson DG. Contractile properties of skinned muscle fibres from young and adult normal and dystrophic (mdx) mice. J Physiol. 1993;460:51–67. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods CE, Novo D, DiFranco M, Capote J, Vergara JL. Propagation in the transverse tubular system and voltage dependence of calcium release in normal and mdx mouse muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2005;568:867–880. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods CE, Novo D, DiFranco M, Vergara JL. The action potential-evoked sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release is impaired in mdx mouse muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2004;557:59–75. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.061291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung EW, Whitehead NP, Suchyna TM, Gottlieb PA, Sachs F, Allen DG. Effects of stretch-activated channel blockers on [Ca2+]i and muscle damage in the mdx mouse. J Physiol. 2005;562:367–380. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Hollingworth S, Baylor SM. Properties of tri- and tetra-carboxylate Ca2+ indicators in frog skeletal muscle fibres. Biophys J. 1996;70:896–916. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79633-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Hollingworth S, Baylor SM. AM-loading of fluorescent Ca2+ indicators into intact single fibres of frog muscle. Biophys J. 1997;72:2736–2747. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78916-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]