Abstract

Although it is known that each spinal cord segment receives thin-fibre inputs from several segmental dorsal roots, it remains unclear how these inputs converge at the cellular level. To study whether C- and Aδ-afferents from different roots can converge monosynaptically on to a single substantia gelatinosa (SG) neurone, we performed tight-seal recordings from SG neurones in the entire lumbar enlargement of the rat spinal cord with all six segmental (L1–L6) dorsal roots attached. The neurones in the spinal cord were visualized using our recently developed oblique LED illumination technique. Individual SG neurones from the spinal segment L4 or L3 were voltage clamped to record the monosynaptic EPSCs evoked by stimulating ipsilateral L1–L6 dorsal roots. We found that one-third of the SG neurones receive simultaneous monosynaptic inputs from two to four different segmental dorsal roots. For the SG neurones from segment L4, the major monosynaptic input was from the L4–L6 roots, whereas for those located in segment L3 the input pattern was shifted to the L2–L5 roots. Based on these data, we propose a new model of primary afferent organization where several C- or Aδ-fibres innervating one cutaneous region (peripheral convergence) and ascending together in a common peripheral nerve may first diverge at the level of spinal nerves and enter the spinal cord through different segmental dorsal roots, but finally re-converge monosynaptically on to a single SG neurone. This organization would allow formation of precise and robust neural maps of the body surface at the spinal cord level.

Thin C- and Aδ-fibre afferents terminating in the superficial dorsal horn of the spinal cord are involved in nociceptive transmission (LaMotte, 1977; Light & Perl, 1979; Cervero & Iggo, 1980; Brown, 1981; Todd & Koerber, 2006). It is known that thin afferents originating from a segmental dorsal root terminate not only in the segment of root entrance but also one to two segments above and below (Szentagothai, 1964; Cruz et al. 1987; Traub & Mendell, 1988; Kato et al. 2004). In other words, any given segment of the spinal cord receives thin-fibre inputs from several dorsal roots. In spite of this obvious input convergence at the level of the spinal cord segment, little is known about its organization at the cellular level. In particular, it is not clear whether C- and/or Aδ-fibres from different segmental dorsal roots can converge monosynaptically on to single SG neurones.

Convergence of C- and Aδ-fibres also plays a principal role in the organization of somatotopic representation maps of the body surface in the spinal cord. Each body surface region has its specific representation in the superficial dorsal horn (Willis & Coggeshall, 1978; Amaral, 2000; Takahashi et al. 2002, 2003). Tracing experiments have clearly shown that the thin afferents from a cutaneous reference point project in a very organized manner to a single narrow field in the ipsilateral SG (Takahashi et al. 2003). Although the central terminals of primary afferents innervating one cutaneous reference point were localized within one spinal cord segment, their labelled cell bodies were found distributed between several segmental dorsal root ganglia (DRGs). These data indicated that the convergence of afferents from different dorsal roots on to one spinal cord segment is the last step in the formation of the somatotopic map of the body surface in the spinal cord. However, the organization of this convergence at the level of single neurones is not yet known, and such knowledge may have important clinical or therapeutic implications.

Therefore, we carried out this study to address the question whether SG neurones can integrate monosynaptic C- and/or Aδ-inputs from several segmental dorsal roots. Such kind of experimentation demands recordings from neurones within the spinal cord with attached dorsal roots. A recently developed imaging technique made it possible to visualize unstained single neurones in the entire spinal cord (Safronov et al. 2007; Pinto et al. 2008). With the help of this technique, we did tight-seal recordings from the L4 SG neurones which are known to receive predominantly cutaneous input from the hindlimb, with only a minor contribution from muscle and visceral afferents (Cervero, 1987; Sugiura et al. 1989, 1993; Ling et al. 2003). All six lumbar segmental dorsal roots were stimulated to record monosynaptic EPSCs in an SG neurone. To study how the convergence pattern changes with the spinal cord segment, we also did recordings from SG neurones in the neighbouring L3 segment.

The principal finding of this study is that one-third of SG neurones receive monosynaptic inputs from two to four different segmental dorsal roots. Based on these results, we propose a new model of primary afferent organization where several C- or Aδ-fibres innervating one cutaneous region (peripheral convergence) and ascending together in a common peripheral nerve may first diverge at the level of spinal nerves and enter the spinal cord through different segmental dorsal roots, but finally re-converge monosynaptically on to a single SG neurone. This organization may be important for formation of precise and robust neural maps of the body surface at the spinal cord level.

Methods

Preparation of the spinal cord with six roots

Visually controlled tight-seal recordings from SG neurones were done using the whole spinal cord preparation (Safronov et al. 2007) with six ipsilateral segmental dorsal roots (L1–L6) attached. Laboratory Wistar rats (3–5 weeks old) were terminally anaesthetised (by intraperitoneal injection of Na+-pentobarbital) and decapitated, in accordance with national guidelines (Direcção Geral de Veterinária, Ministério da Agricultura) and the institutional Ethics Committee. The vertebral column was quickly cut out and immersed in ice-cold oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF). The whole lumbar enlargement with unilaterally attached L1–L6 dorsal roots (length, 5–17 mm) was dissected and glued with cyanoacrylate adhesive to a 1 mm thick metal plate as shown in Fig. 1A (the lateral spinal cord surface was up). A tissue slicer (Leica VT 1000S, Germany) was used to cut the lateral white matter and create an access to grey matter. In order to maximally preserve the C- and Aδ-afferent input to the spinal SG, the rostrocaudal extension of the cut at the level of the dorsal grey matter did not exceed the length of one spinal segment. Furthermore, the depth of the cut was adjusted to preserve the dorsal root entry zone and an additional 200–300 μm of grey matter laterally. To make a preparation for the recording from the L4 SG neurones, the vibrating blade of the tissue slicer (without forward movement) was first deepened by 100–200 μm (at the level of the SG) into the spinal cord on the border between segments L3 and L4, and then the blade was moved forward in the caudal direction. The blade left the spinal white matter at the level of the narrower segment L5. For recordings from the L3 SG neurones, the blade was first deepened into the grey matter on the L2–L3 border and the spinal cord was cut until the L3–L4 border, where the cut part was removed with scissors. Thus, only the lateral part of the segment L3 was removed. After incubation for 45 min at 33°C, the spinal cord with the metal plate was transferred into the recording chamber where the metal plate provided mechanical stability of the preparation. All measurements were done at 22–24°C.

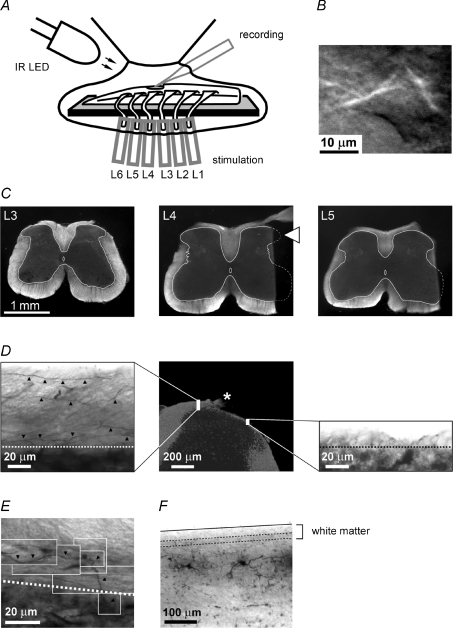

Figure 1. Tight-seal recording from SG neurones in the entire spinal lumbar enlargement.

A, preparation on the entire lumbar enlargement of the spinal cord with preserved unilateral six dorsal roots, L1–L6. The roots were stimulated through suction electrodes. The neurones in the SG were viewed using oblique illumination by infrared LED. B, an image of an SG neurone within the spinal cord. Depth, 43 μm. C, cross sections cut from the fixed spinal cord. The sections of segments L3, L4 and L5 are shown from the preparation used for recordings from the L4 SG neurones. White lines show the border of the grey matter. The border of the grey matter in the cut part of the L4 section is shown as a symmetrical projection of the intact contralateral half. The region of the SG exposed for the patch-clamp recording is indicated by a white arrowhead in segment L4. The images were taken using room illumination (condenser illumination and LED were off) and digitally inverted. D, distribution of ascending and descending primary afferents in the dorsal white matter of a 27-day-old rat. Parasagittal sections from medial (left) and lateral (right) dorsal white matter were from regions indicated on the cross section of the dorsal horn (middle). The cut dorsal root is indicated by an asterisk. In the medial dorsal white matter, several biocytin-labelled thin afferents are indicated by filled arrowheads. In the narrow lateral white matter (right) no stained afferents were detected. Dotted lines show the border between the white and grey matter (in D and E). E, parasagittal section of medial dorsal white matter showing a thin primary afferent entering the grey matter. Parts of the image were taken in different focal planes. F, a 100-μm-thick parasagittal section of the spinal cord with two biocytin-labelled SG neurones. Two dotted lines show the dorsal and ventral borders of the white matter in the focal plane (top of the section). Continuous line shows the dorsal border of the white matter from the bottom of the section.

Visualization of SG neurones

SG (lamina II) neurones were visualized in the whole spinal cord using the oblique LED illumination technique previously described (Safronov et al. 2007). In the present study we used an infrared LED positioned outside the solution meniscus (Fig. 1A). One improvement was achieved, in comparison with the original description. In this study, we used a more powerful infrared LED (L850F-02U, Marubeni, Japan) with an emission peak at 850 nm, narrow beam of ±5 deg and maximum radiant intensity of 270 mW sr−1. This allowed us to reduce exposure times of the black-and-white digital CCD camera (C4742–95, Hamamatsu, Japan) to 5–30 ms and therefore to increase the frame rate. When positioning the preparation in the recording chamber, care was taken to avoid direct shadow imposed by the dorsal roots on the cut spinal cord surface. The SG neurones (Fig. 1B) were identified as cells with a soma diameter of about 10 μm located 20–80 μm away from the dorsal border of the grey matter. Distances from the border are indicated in Table 1 for each SG neurone with converging inputs.

Table 1.

Converging inputs to the L4 and L3 SG neurones

| Cell | Age (days) | Firing type | Distance (μm) | L1 |

L2 |

L3 |

L4 |

L5 |

L6 |

Input from roots | Converging roots | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Aδ | C | Aδ | C | Aδ | C | Aδ | C | Aδ | C | Aδ | ||||||

| SG neurone in L4 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 23 | AFN | 60 | — | — | — | — | — | — | • | — | • | — | • | — | 3C | 3 |

| 2 | 21 | TFN | 70 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | • | — | • | — | 2C | 2 |

| 3 | 35 | TFN | 70 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | • | — | • | — | 2C | 2 |

| 4 | 22 | TFN | 30 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | • | — | • | — | 2C | 2 |

| 5 | 25 | TFN | 70 | — | — | — | — | — | — | • | ○ | • | ○ | • | — | 3C+2Aδ | 3 |

| 6 | 23 | AFN | 40 | • | — | — | — | — | — | • | ○ | — | — | — | — | 2C+1Aδ | 2 |

| 7 | 24 | TFN | 70 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ○ | • | — | — | — | 1C+1Aδ | 2 |

| 8 | 23 | AFN | 40 | — | — | — | — | — | ○ | — | ○ | — | ○ | • | — | 1C+3Aδ | 4 |

| 9 | 23 | TFN | 60 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ○ | — | ○ | 2Aδ | 2 |

| SG neurone in L3 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 | 32 | AFN | 40 | — | — | • | — | — | — | • | — | • | — | — | — | 3C | 3 |

| 11 | 32 | TFN | 60 | — | — | • | — | • | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2C | 2 |

| 12 | 32 | DFN | 80 | • | — | — | — | • | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2C | 2 |

| 13 | 32 | TFN | 30 | — | — | — | — | — | — | • | — | • | — | — | — | 2C | 2 |

| 14 | 24 | TFN | 30 | — | — | — | — | • | — | • | ○ | — | — | — | — | 2C+1Aδ | 2 |

| 15 | 24 | TFN | 30 | — | — | — | — | — | — | • | — | — | ○ | — | — | 1C+1Aδ | 2 |

| 16 | 23 | DFN | 70 | — | — | — | ○ | — | — | • | — | — | — | 1C+1Aδ | 2 | ||

| 17 | 21 | TFN | 75 | — | — | — | — | • | ○ | — | ○ | — | ○ | — | — | 1C+3Aδ | 3 |

This table describes only the neurones with monosynaptic inputs from at least two segmental dorsal roots. For each segment, the SG neurones were arranged in the order of decreasing dominance of C- over Aδ-fibre inputs. TFN, AFN and DFN are tonic, adapting and delayed-firing neurones, respectively. The distance was measured between the dorsal border of the spinal grey matter and the middle of the cell body. Monosynaptic C- and Aδ-fibre inputs are indicated by filled and open circles, respectively. In the last but one column, the input from roots is given as n1C +n2Aδ, where n1 and n2 are the numbers of different segmental dorsal roots with monosynaptic C- and Aδ-fibre projections, respectively. In the last column, the number of converging roots is the number of segmental dorsal roots with monosynaptic C-/Aδ-inputs. In cell 16, two rootlets of the L3 dorsal root were damaged.

Histological analysis

Histological analysis was done to confirm that our tissue cut was limited to one segment and did not damage major ascending and descending pathways of thin afferents and that the neurones studied were located in the SG. The spinal cord used for the L4 SG neurone recording was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight. Serial sections of 100 μm thickness were cut with a tissue slicer at the level of segments L3, L4 and L5 (Fig. 1C) and mounted on gelatine-coated glass slides. After drying, the sections were stained with 1% toluidine blue solution for 1–2 min, dehydrated with ethanol (96% and absolute), treated in xylene and coverslipped. Photographs of the sections were taken with a Zeiss Axioskop microscope. As expected, segment L3 was intact (Fig. 1C). At the L4 level, the dorsal root entry zone remained intact together with 200–300 μm of more lateral dorsal horn. Toluidine blue staining of neuronal cell bodies observed at high magnification confirmed that lamina I (most dorsal 20 μm layer) and lamina II were present on the cut surface. At segment L5, the entire dorsal grey matter was preserved and only some dorsolateral white matter and the lateral part of ventral horn were removed. Thus, in all six lumbar segments both the dorsal root entry zones and the medial part of Lissauer's tract, where thin afferents from adjacent roots ascend or descend to reach the segment L4 (Szentagothai, 1964), were preserved.

The dorsolateral white matter has been suggested to contain mostly propriospinal fibres (Szentagothai, 1964) and it is very thin in young rats. To confirm that the lateral cut of white matter did not affect major ascending and descending afferent pathways in our animals, we stained the primary afferent fibres and studied their distribution in the dorsal white matter (Fig. 1D). The intact spinal cord with attached L4 root was dissected and placed in a chamber filled with ACSF. The root was placed on a rubber block and biocytin crystals were deposited on its cut end. The spinal cord was incubated at room temperature for 5 h and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight. Serial parasagittal sections of 100 μm thickness were cut with a tissue slicer. To reveal the biocytin, the free-floating sections were permeabilized with 50% ethanol, treated according to the avidin–biotinylated horseradish peroxidase method (ExtrAvidin-Peroxidase, diluted 1 : 1000, Sigma) and the histochemical reaction was completed with a diaminobenzidine (Sigma) chromogen reaction. Sections were counterstained with 1% toluidine blue, dehydrated and mounted with DPX (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland). Photographs were taken with a Zeiss Primo Star microscope equipped with an AVT Guppy digital camera. Contrast and brightness of the images was adjusted using Adobe Image Ready software. The cross-section of the dorsal horn showing the white matter regions sectioned in the parasagittal plane is presented in Fig. 1D (middle). The medial dorsal white matter had a thickness of about 70 μm (Fig. 1D left, the border between the white and grey matter is indicated by a dotted line) and many labelled ascending or descending thin afferents could be seen in each focal plane (indicated by filled arrowheads). Some of these afferents were seen to enter the grey matter (Fig. 1E). In contrast, the dorsolateral white matter was much thinner (about 10–20 μm), had an irregular appearance and did not contain visible afferents (Fig. 1D, right). Therefore, one could conclude that the cut of the lateral white matter in our preparation did not affect the major afferent inputs to the dorsal grey matter.

Since thin afferents entering the grey matter in the dorsal root entry zone generally project laterally to terminate in the lateral SG, we can conclude that the neurones located near the cut surface (indicated by the white arrowhead in Fig. 1C, middle) preserved the major part of thin afferent inputs from their segmental and adjacent dorsal roots. However, an unavoidable cut of the most lateral dendrites of SG neurones in our preparation might result in some loss of inputs. For this reason, the degree of afferent fibre convergence on to SG neurones described here may be an underestimation of that in intact spinal cord.

To confirm the location of studied neurones in the SG, in nine whole-cell recordings 0.5% biocytin was added to the pipette solution. The spinal cords were then fixed and processed as described above. Successful recovery was achieved for five neurones, all of which had cell bodies located in the SG. A parasagittal section of 100 μm thickness with two stained neurones is shown in Fig. 1F.

Electrophysiology

Tight-seal whole-cell recordings from SG neurones were performed as previously described (Melnick et al. 2004a, b) in ACSF containing (mm): NaCl 115, KCl 3, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1, glucose 11, NaH2PO4 1, NaHCO3 25 (pH 7.4 when bubbled with 95%–5% mixture of O2–CO2). EPSCs evoked by the stimulation of attached dorsal roots were recorded in SG neurones using EPC9 or EPC10 amplifiers (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany). The patch pipettes were pulled from thick-walled borosilicate glass tubes with 1.5 mm outer diameter and 0.86 mm inner diameter (Modulohm, Denmark) and after fire-polishing had a resistance of 3–5 MΩ. The pipette solution contained (mm): KCl 3, potassium gluconate 150, MgCl2 1, BAPTA 1 and Hepes 10 (pH 7.3 adjusted with KOH, final [K+] was 161 mm). The signal was low-pass filtered at an effective corner frequency of 2.9 kHz and sampled at 10–20 kHz. Offset potentials were compensated directly before the seal formation. Liquid junction potentials were calculated and corrected for in all experiments. The series resistance measured in the current-clamp mode was below 14 MΩ and was not compensated. The mean input resistance of the neurones was 2.2 ± 0.3 GΩ (n= 52) and the mean resting potential measured with balanced amplifier input (Santos et al. 2004) was −70.6 ± 1.8 mV (n= 52). According to intrinsic firing properties, the SG neurones were classified as tonic-firing neurones (TFNs), adapting-firing neurones (AFNs) and delayed-firing neurones (DFNs) using criteria previously described (Santos et al. 2004, 2007). All numbers are given as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). The present study is based on recordings from 52 SG neurones and 15 isolated dorsal roots.

Stimulation of six dorsal roots

Each of six dorsal roots was inserted into a suction electrode fabricated from borosilicate glass tube with 1.5 mm outer diameter and 0.86 mm inner diameter (Modulohm). The electrodes were fire-polished to fit the size of the roots and mechanically fixed on a common holder controlled by a manipulator. An isolated pulse stimulator (2100, A-M Systems, Carlsborg, USA) connected via a six-position switcher was used for sequential stimulation of roots L1–L6. Precautions were taken to avoid unspecific cross-stimulation of roots via neighbouring suction electrodes. For this, each of six suction pipettes had its own reference electrode with its surface insulated except for the last 1 mm positioned closely to the pipette opening with the inserted root. To test whether the suction electrodes in our stimulation system could non-specifically activate neighbouring roots, we performed five experiments in which the patch-clamp amplifier was used to record compound action potential currents (CAPCs, see Pinto et al. 2008) from isolated dorsal root, the other end of which was stimulated through one of our middle suction electrodes. Neighbouring suction electrodes were also filled with dorsal roots which were not connected to the recording system. Application of 100 μA current (duration, 1 ms) to the middle suction electrode fully activated both C- and Aδ-components of CAPCs in the recorded root. Stimulation of both neighbouring suction electrodes at intensities as high as 10 mA did not result in the appearance of any measurable CAPCs in the recorded root (n= 5). Therefore, at stimulation intensities used in these experiments the cross-stimulation of roots by neighbouring suction electrodes was unlikely.

To study the EPSC inputs to SG neurones, the roots were stimulated by 100 μA current pulses (duration, 1 ms), which according to our previous results were supramaximal for activating both C- and Aδ-fibres (Pinto et al. 2008). At the beginning of each experiment, all roots were additionally tested at 150 μA (duration, 1 ms) to confirm that neither the number nor the magnitudes of EPSCs could be further increased. We identified the EPSCs as Aδ-fibre-mediated if they remained after the pulse duration was reduced to 50 μs and conduction velocity of the afferent was between 0.5 and 3.5 m s−1 (Pinto et al. 2008). The EPSCs were identified as C-fibre-mediated if they disappeared at 50 μs pulses and the afferent conduction velocity was below 0.55 m s−1 (Pinto et al. 2008). Conduction velocities were calculated from latencies of corresponding EPSCs measured from the end of a 50 μs pulse for Aδ-fibres and from the middle point of a 1 ms pulse for C-fibres (with a 1 ms allowance for synaptic transmission). The conduction distance included the length of the root from the opening of the suction electrode to the dorsal root entry zone and the estimated pathway within the spinal cord. Stimulus utilization time, i.e. the delay between the stimulus and beginning of the spike in the axon (Waddel et al. 1989), was not taken into account.

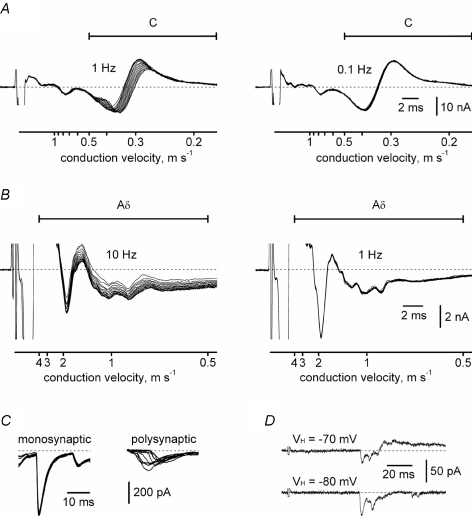

Classification of monosynaptic EPSCs

To adequately choose the stimulation frequency for identifying the monosynaptic EPSCs, we first isolated dorsal roots (L4, L5 or L6) and recorded C- and Aδ-fibre CAPCs at different frequencies. C-fibre CAPCs were evoked at 1 Hz, 0.5 Hz, 0.2 Hz and 0.1 Hz. At 1 Hz, C-fibre CAPCs showed progressive increase in their latency and a reduction in the amplitude (Fig. 2A, n= 5, see also Gee et al. 1996). A similar effect, although less pronounced, was also observed at 0.5 Hz and 0.2 Hz (not shown). At 0.1 Hz, the C-component became more stable (Fig. 2A) and the ratio of the latency variation to the mean latency measured for 15 consecutive traces at zero current level (dashed line) was 2.4 ± 0.4% (n= 5). Aδ-fibre CAPCs were evoked at 10 Hz, 5 Hz and 1 Hz. At 10 Hz and 5 Hz stimulations, the slowest parts of the Aδ-fibre CAPCs with a conduction velocities between 0.5 and 2 m s−1 were unstable (Fig. 2B, n= 5, shown for 10 Hz). At 1 Hz, the Aδ-fibre CAPCs became stable in the whole range of their conduction velocities (Fig. 2B, n= 5). Based on these data, the C-fibre-mediated EPSCs were considered as monosynaptic if there was no failure and the latency variation was less than 1 ms during 10 consecutive stimulations at 0.1 Hz. Aδ-fibre-mediated EPSCs were considered as monosynaptic if the latency variation was less than 1 ms and there was no failure in 10 consecutive stimulations with 1 ms and 50 μs pulses at 1 Hz. For 10 EPSCs the monosynaptic nature was additionally confirmed by unchanged latency in 5 mm Ca2+ and 5 mm Mg2+ ACSF (Jahr & Jessell, 1985). A root with multiple C- or Aδ-fibre inputs to an SG neurone was considered as projecting monosynaptically if at least one EPSC was identified as monosynaptic. EPSCs that did not fulfil these criteria and all IPSCs were classified as polysynaptic. Examples of monosynaptic C-fibre-mediated EPSCs and polysynaptic EPSCs are shown in Fig. 2C. During root stimulation an SG neurone was held at two potentials, −80 mV and −70 mV (Fig. 2D). At −80 mV the EPSCs could be analysed without superimposed IPSCs (ECl=−80 mV). The monosynaptic EPSCs were completely blocked by the glutamate AMPA receptor antagonist CNQX (10 μm; n= 5).

Figure 2. Testing the stimulation frequency in isolated dorsal roots.

A, recordings of C-fibre CAPCs in isolated dorsal roots (L4, conduction distance, 4.5 mm). Each family of traces has 15 consecutive (individual) recordings of CAPCs activated at 1 Hz and 0.1 Hz. Fast A-components are truncated. B, Aδ-fibre CAPCs in isolated dorsal roots (L5, conduction distance, 10 mm). Each of 15 traces shown at 10 Hz and 1 Hz stimulation is an average of 20 individual traces. In experiments with Aδ-fibre CAPCs, a protocol with 15 stimulations at a given frequency was repeated 20 times (with 4 s intervals between protocols) and the corresponding episodes were averaged. C, examples of mono- and polysynaptic EPSCs recorded in an SG neurone. Each group is a superposition of 10 consecutive recordings. Holding potential was −70 mV. D, examples of recordings from an SG neurone held at −70 and −80 mV. Both EPSCs and IPSCs were seen at −70 mV, whereas only EPSCs were seen at −80 mV.

Results

Fifty-two SG neurones from spinal segments L4 (n= 34) and L3 (n= 18) were tested for receiving monosynaptic C- and Aδ-inputs from the L1–L6 dorsal roots. In 14 SG neurones (27%; L4, n= 9; L3, n= 5) no monosynaptic input was observed. In 21 neurones (40%; L4, n= 16; L3, n= 5), monosynaptic input of either C- or Aδ-type from only one root was recorded. The remaining 17 SG neurones (33%) were found to receive monosynaptic C- or Aδ-afferent inputs from more than one segmental dorsal root. These 17 neurones (L4, n= 9; L3, n= 8) with converging monosynaptic inputs form the basis of this report. Detailed description of their inputs is presented in Table 1. Analysis of polysynaptic connections was beyond the scope of this study.

Inputs of the L4 SG neurones

Nine SG neurones located in the spinal cord segment L4 received inputs from more than one root. In Table 1 these cells are shown arranged in order of decreasing dominance of C- over Aδ-fibre inputs. Four SG neurones received only C-fibre inputs (cells 1–4), four neurones received both C- and Aδ-inputs (cells 5–8) and one neurone received solely Aδ-input (cell 9).

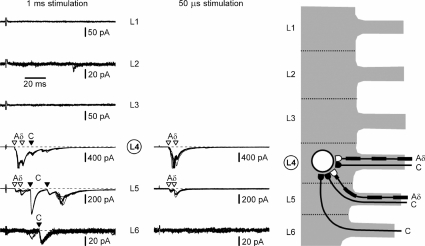

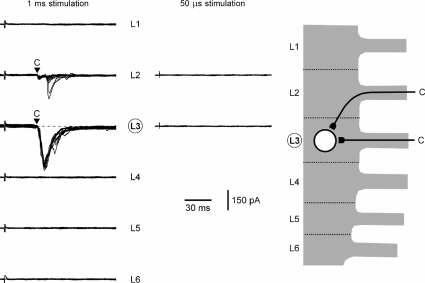

Recordings from an SG neurone receiving C-fibre inputs from three segmental dorsal roots and Aδ-inputs from two roots (cell 5) are shown in Fig. 3. First, the L1–L6 roots were stimulated with 1 ms pulses (100 μA) and EPSCs in the neurone were recorded (left column). Roots L1 and L3 did not show inputs. The L2 dorsal root had only a polysynaptic C-fibre-mediated EPSC which was not analysed further. The L4 root stimulation evoked three monosynaptic EPSCs of which two had latencies corresponding to Aδ- (open triangles) and one to C- (filled triangle) afferent conduction velocities. Stimulation of the L5 dorsal root elicited two Aδ- (open triangles) and two C- (filled triangles) fibre-mediated monosynaptic EPSCs as well as some polysynaptic EPSCs (not analysed). The L6 root stimulation activated one monosynaptic C-fibre EPSC (filled triangle) and polysynaptic currents. To confirm the EPSC classification based on fibre conduction velocities, responding roots L4, L5 and L6 were also stimulated with 50 μs pulses (middle column). In all cases, the Aδ-afferent-mediated EPSCs remained, whereas the C-fibre-mediated currents disappeared. The estimated monosynaptic input of this SG neurone is shown in Fig. 3 (right). The L4 and L5 roots innervated this neurone via both Aδ- and C-afferents and the L6 root innervation was restricted to C-afferents. Thus, this SG neurone received monosynaptic innervation from three different roots (L4, L5 and L6).

Figure 3. Recording from the L4 SG neurone with dominating C-input.

Left, recordings of EPSCs elicited in one L4 SG neurone by stimulation of L1–L6 segmental dorsal roots using 1 ms pulses (100 μA). Holding potential was −70 mV. Monosynaptic C- and Aδ-fibre-mediated EPSCs are indicated by filled and open triangles, respectively. The triangles also show the time moment for which the latency analysis was done. Middle, roots with monosynaptic connections (L4, L5 and L6) were also stimulated with 50 μs pulses (100 μA). Holding potential was −70 mV. Here and in the following figures, recordings are shown as a superposition of 10 consecutive traces for roots with monosynaptic inputs (indicated by triangles) and 5 consecutive traces for roots without monosynaptic input. Right, schematic drawing of monosynaptic innervation of this SG neurone by C- and Aδ-afferents originating from the L4, L5 and L6 segmental dorsal roots.

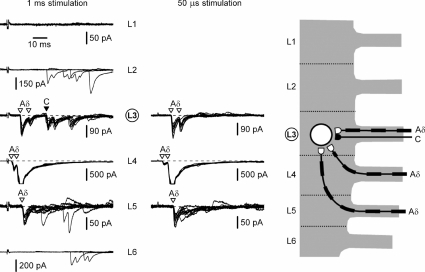

An example of recordings from another SG neurone with a dominating Aδ-input (cell 8) is shown in Fig. 4. The same stimulation protocol was used to identify monosynaptic Aδ-afferent inputs from three different roots (L3, L4 and L5) and a C-fibre input from the L6 root. The total innervation of this SG neurone originated from four different roots (L3, L4, L5 and L6).

Figure 4. Recording from the L4 SG neurone with dominating Aδ-input.

Left, recordings of EPSCs elicited in an L4 SG neurone by the L1–L6 root stimulation with 1 ms pulses. Holding potential was −70 mV. Middle, roots with monosynaptic connections (L3, L4, L5 and L6) were also stimulated with 50 μs pulses. Holding potential was −80 mV. Here and in the following figures, the voltage-gated Na+ currents activated by EPSCs were truncated. Right, suggested organization of monosynaptic innervation of this SG neurone by C- and Aδ-afferents from the L3, L4, L5 and L6 segmental dorsal roots.

Thus, our recordings (see Table 1) have shown that: (1) SG neurones in the L4 segment can receive converging thin fibre inputs from as many as four different roots; (2) with the exception of one neurone (cell 6), the converging inputs arose from adjacent roots; and (3) the converging inputs mostly were from L4–L6 roots.

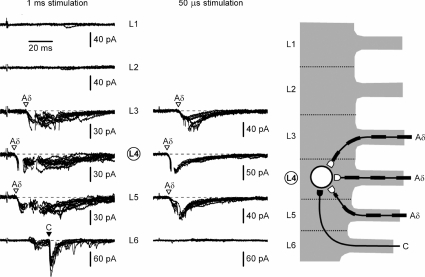

Inputs of the L3 SG neurones

In order to study whether the root innervation pattern is shifted with the segmental location of an SG neurone, we also recorded from cells in spinal segment L3. Eight SG neurones from L3 received monosynaptic inputs from more than one dorsal root (Table 1). Four neurones received only C-fibre inputs (cells 10–13) while the other four received both C- and Aδ-innervation (cells 14–17). Recordings from one SG neurone with only C-fibre inputs (cell 11) are shown in Fig. 5. This neurone received innervation from the L2 and L3 segmental dorsal roots. Another SG neurone with dominating Aδ-fibre inputs is shown in Fig. 6 (cell 17). This SG neurone had a strong monosynaptic Aδ-afferent innervation from the L3, L4 and L5 segmental dorsal roots. The only monosynaptic C-fibre input was from the L3 dorsal root. This neurone also showed large number of polysynaptic EPSCs and IPSCs. The total number of converging roots was three (Fig. 6, right).

Figure 5. An SG neurone from the segment L3 with only C-fibre input.

Left, recordings of EPSCs evoked in one L3 SG neurone by the L1–L6 root stimulations with 1 ms pulses. Holding potential was −70 mV. Middle, roots giving monosynaptic inputs (L2 and L3) were also tested with 50 μs pulses. Holding potential was −70 mV. Right, suggested organization of monosynaptic C-fibre inputs to this SG neurone from the L2 and L3 segmental dorsal roots.

Figure 6. An SG neurone from the segment L3 with dominating Aδ-fibre input.

Left, EPSCs recorded in one L3 SG neurone after the stimulations of L1–L6 dorsal roots with 1 ms pulses. Holding potential was −70 mV. Middle, roots giving monosynaptic inputs (L3, L4 and L5) were also tested with 50 μs pulses. Holding potential was −70 mV. Right, suggested organization of monosynaptic C- and Aδ-fibre inputs to this SG neurone from the L3, L4 and L5 segmental dorsal roots.

Thus, the pattern of the thin afferent convergence on to SG neurones in the segment L3 was similar to that described for L4, but it was shifted along the rostrocaudal axis (see Table 1). Converging inputs mostly arose from L2–L5 roots.

Picrotoxin does not increase the number of converging roots

Since tonic GABAergic inhibition of afferent terminals, originally described for myelinated long-range A-type afferents (Wall & Bennett, 1994), might also be the reason for lacking C- and Aδ-inputs in apparently silent roots, we tested whether the application of 100 μm picrotoxin can increase the number of converging roots. Recordings were done from eight SG neurones located in segment L4. Three of these cells had monosynaptic inputs from two different roots, which are specified in Table 1 (cells 3, 4 and 7). The remaining five SG neurones had monosynaptic input from only one root (3 neurones with C-input; 1 neurone with both C- and Aδ-inputs and 1 neurone with Aδ-input). In all these eight experiments, 100 μm picrotoxin neither increased the number of converging roots nor changed the type of input from a given root.

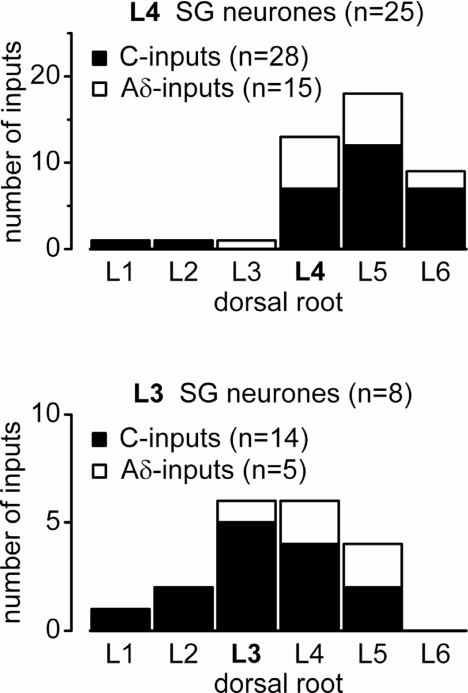

Total input to the L4 and L3 segments

To describe the total input to SG neurones located in the spinal segments L4 and L3, we built two histograms including all neurones receiving monosynaptic C-/Aδ-fibre inputs from at least one segmental dorsal root (Fig. 7). The SG neurones located in segment L4 (n= 25) received their major thin fibre inputs (40 of 43) from the segmental dorsal roots L4, L5 and L6. The principal input to the L3 segment was shifted leftwards. The L3 SG neurones (n= 8) were mostly innervated through the L2–L5 dorsal roots (18 of 19 inputs).

Figure 7. Total inputs to the L4 and L3 SG neurones from the L1–L6 roots.

Histograms showing the numbers of total inputs observed in the SG neurones located in spinal segments L4 and L3. These histograms include all cells with a monosynaptic input from at least one dorsal root. Neurones were included only if the preparation had all 6 roots undamaged.

Discussion

We used the oblique LED illumination technique (Safronov et al. 2007) to visualize SG neurones in the spinal cord preparation containing the entire lumbar enlargement with six attached segmental dorsal roots, in order to investigate the monosynaptic convergence of C- and Aδ-afferents at the cellular level. The basic finding of the present study is that one-third of SG neurones receive monosynaptic inputs from more than one segmental dorsal root and some SG neurones receive their C-/Aδ-inputs from as many as four different roots.

It is known from a number of anatomical studies that thin afferents originating from a dorsal root terminate in the spinal cord segment of the root entrance as well as one to two segments above and below (Szentagothai, 1964; Cruz et al. 1987). Similarly, blind whole-cell recordings showed that the SG neurones with monosynaptic input from root L5 may be found two segments away from the root entrance segment (Kato et al. 2004). The SG of a given spinal segment is therefore integrating sensory inputs from several neighbouring dorsal roots. Our present data can help to understand how this intersegmental integration occurs. A subpopulation of SG neurones described here receives monosynaptic C-/Aδ-inputs from several segmental dorsal roots and might be specialized for this type of sensory processing. Almost half of these neurones (8 of 17; see Table 1) were exclusively integrating the C-afferent inputs from two to three different roots. The other half of the SG neurones (8 of 17) received mixed C- and Aδ-inputs from two to four segmental dorsal roots. Thus, the maximum number of different roots converging monosynaptically on to a single neurone as well as an overall dominance of C- over Aδ-inputs reported here are in a good agreement with classical anatomical studies of thin afferent fibres innervating the SG.

Myelinated long-range A-type afferents may also extend their arborizations beyond the area in which neuronal responses to afferent stimulation could be observed (Traub et al. 1986; Wall & Bennett, 1994; Wall, 1995; Lidierth, 2007). Distal terminals of these afferents appeared silent under normal conditions due to a tonic presynaptic inhibition which could be relieved by the GABAA receptor blocker picrotoxin but not the glycine receptor blocker strychnine (Wall & Bennett, 1994). Here we found that the application of picrotoxin did not increase the number of converging roots with C- and Aδ-fibre inputs to the SG neurones. Therefore, functional monosynaptic inputs recorded under physiological conditions seem to correspond well to the anatomical extent of thin afferent arborizations in the SG. One cannot exclude, however, that the long-range projecting myelinated afferents (Traub et al. 1986; Lidierth, 2007) terminate in regions other than the SG where our sampled cells were located.

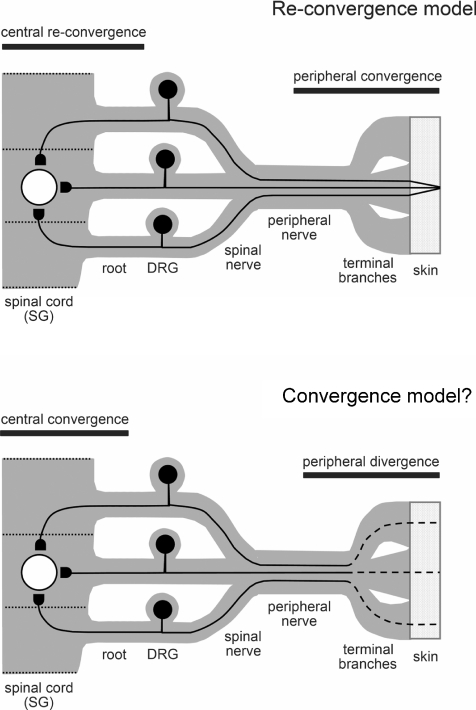

The superficial dorsal horn has somatotopic organization, i.e. different cutaneous regions are represented in an orderly fashion to form the precise spinal map of the body surface (Willis & Coggeshall, 1978; Amaral, 2000). A large body of data about projections of cutaneous regions to the superficial dorsal horn originates from electrophysiological experiments with whole animals recording neuronal responses to receptive field stimulation (Brown & Fuchs, 1975; Bennett et al. 1980; Woolf & Fitzgerald, 1983; Woolf & King, 1989; Furue et al. 1999). However, large receptive fields of spinal neurones observed in these studies can imply involvement of both mono- and polysynaptic inputs from stimulated cutaneous afferents. More precise spinal maps of peripheral projections were obtained by point-injecting a neurotracer to different cutaneous regions (Molander & Grant, 1985; Takahashi et al. 2003). In these experiments, a labelled projection field in the superficial dorsal horn indicates the precise location of neurones receiving monosynaptic C- and Aδ-afferent inputs from a given cutaneous reference point. Although the afferents from a single reference point generally projected to a single SG field within one spinal cord segment, their labelled cell bodies were frequently found in more than three different segmental DRGs (Takahashi et al. 2003). In some cases, the DRGs of neighbouring segments had comparable or even higher numbers of labelled neurones than the DRG of the segment containing the SG projection field. The fact that the afferents from the neighbouring roots/DRGs did not visibly label the SG projection field in their own spinal cord segment can imply that the major central projection field of a given afferent is determined by the location of its peripheral ending. Thus, different segment afferents innervating a common cutaneous reference point project to the same SG field in accordance with the somatotopic principle. In the context of our present finding, the monosynaptic convergence of different segment afferents on to SG neurones may be the last step in the fine adjustment of the somatotopic map (Fig. 8, Re-convergence model). An alternative model, in which converging afferents originate from different terminal branches of a common peripheral nerve (Fig. 8, Convergence model), would imply a monosynaptic projection of very broad cutaneous regions to the same SG receptive field and therefore would be in principal contradiction with the rigorous arrangement of peripheral and central fields of dermatomes determined by point-injection of a neurotracer (Takahashi et al. 2003).

Figure 8. Proposed model for the thin afferent convergence on to an SG neurone.

Re-convergence model, three converging fibres originate from one cutaneous reference point, ascend in a common peripheral nerve and diverge at the level of segmental spinal nerves, in order to re-converge again on to an SG neurone. The Re-convergence model was developed to explain formation of precise and robust somatotopic maps and to comply with observations of Takahashi et al. (2003). Convergence model, in this alternative model three centrally converging afferents originate from different terminal branches of a common peripheral nerve. In the Convergence model, the peripheral divergence strongly increases the cutaneous area projecting to a single SG receptive field.

Based on the present data, we propose a model of primary afferent organization where C- or Aδ-fibres innervating one cutaneous region (peripheral convergence) and ascending together in a common peripheral nerve may first diverge at the level of spinal nerves and enter the spinal cord through different segmental dorsal roots, but finally re-converge monosynaptically on to SG neurones (Re-convergence model, Fig. 8). This model complies well with both (1) the clinical observation that cutting the distal portion of a peripheral cutaneous nerve results in a complete loss of sensory inputs from the area innervated by the nerve, whereas damage to a dorsal root often results in a small sensory deficit (Gardner et al. 2000) and (2) experimental findings that a cutaneous reference point orderly projects to a single central receptive field via a multi-dorsal-root pathway (Takahashi et al. 2003). Thus, the organization proposed would allow formation of precise and, at the same time, robust neural maps of the body surface at the spinal cord level.

In conclusion, we have shown that the C- and Aδ-afferents from different segmental dorsal roots can monosynaptically converge on to single SG neurones. This convergence may be important for both the integration of the peripheral sensory input and the formation of precise somatotopic maps.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Eric Guire for critically reading the manuscript. The work was supported by a grant from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology funded by POCTI2010 and FEDER (to B.V.S.) and a NIH grant NS27037 (to T. R. Soderling and V. A. D.).

References

- Amaral DG. The Functional Organization of Perception and Movement. In: Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM, editors. Principles of Neural Science. 4th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York; 2000. pp. 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GJ, Abdelmoumene M, Hayashi H, Dubner R. Physiology and morphology of substantia gelatinosa neurons intracellularly stained with horseradish peroxidase. J Comp Neurol. 1980;194:809–827. doi: 10.1002/cne.901940407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AG. Organization in the Spinal Cord. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Brown PB, Fuchs JL. Somatotopic representation of hindlimb skin in cat dorsal horn. J Neurophysiol. 1975;38:1–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.1975.38.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervero F. Dorsal horn neurones and their sensory inputs. In: Yasksh TL, editor. Spinal Afferent Processing. New York: Plenum Press; 1987. pp. 197–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cervero F, Iggo A. The substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord: a critical review. Brain. 1980;103:717–772. doi: 10.1093/brain/103.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz F, Lima D, Coimbra A. Several morphological types of terminal arborizations of primary afferents in laminae I–II of the rat spinal cord, as shown after HRP labeling and Golgi impregnation. J Comp Neurol. 1987;261:221–236. doi: 10.1002/cne.902610205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furue H, Narikawa K, Kumamoto E, Yoshimura M. Responsiveness of rat substantia gelatinosa neurones to mechanical but not thermal stimuli revealed by in vivo patch-clamp recording. J Physiol. 1999;521:529–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EP, Martin JM, Jessell TM. The bodily senses. In: Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM, editors. Principles of Neural Science. 4th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York; 2000. pp. 430–449. [Google Scholar]

- Gee MD, Lynn B, Cotsell B. Activity-dependent slowing of conduction velocity provides a method for identifying different functional classes of C-fibre in the rat saphenous nerve. Neuroscience. 1996;73:667–675. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahr CE, Jessell TM. Synaptic transmission between dorsal root ganglion and dorsal horn neurons in culture: antagonism of monosynaptic excitatory postsynaptic potentials and glutamate excitation by kynurenate. J Neurosci. 1985;5:2281–2289. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-08-02281.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato G, Furue H, Katafuchi T, Yasaka T, Iwamoto Y, Yoshimura M. Electrophysiological mapping of the nociceptive inputs to the substantia gelatinosa in rat horizontal spinal cord slices. J Physiol. 2004;560:303–315. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMotte C. Distribution of the tract of Lissauer and the dorsal root fibers in the primate spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1977;172:529–561. doi: 10.1002/cne.901720308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidierth M. Long-range projections of Aδ primary afferents in the Lissauer tract of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2007;425:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light AR, Perl ER. Reexamination of the dorsal root projection to the spinal dorsal horn including observations on the differential termination of coarse and fine fibers. J Comp Neurol. 1979;186:117–131. doi: 10.1002/cne.901860202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling LJ, Honda T, Shimada Y, Ozaki N, Shiraishi Y, Sugiura Y. Central projection of unmyelinated (C) primary afferent fibers from gastrocnemius muscle in the guinea pig. J Comp Neurol. 2003;461:140–150. doi: 10.1002/cne.10619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick IV, Santos SF, Safronov BV. Mechanism of spike frequency adaptation in substantia gelatinosa neurones of rat. J Physiol. 2004a;559:383–395. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.066415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick IV, Santos SF, Szokol K, Szucs P, Safronov BV. Ionic basis of tonic firing in spinal substantia gelatinosa neurons of rat. J Neurophysiol. 2004b;91:646–655. doi: 10.1152/jn.00883.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molander C, Grant G. Cutaneous projections from the rat hindlimb foot to the substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord studied by transganglionic transport of WGA-HRP conjugate. J Comp Neurol. 1985;237:476–484. doi: 10.1002/cne.902370405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto V, Derkach VA, Safronov BV. Role of TTX-sensitive and TTX-resistant sodium channels in Aδ- and C-fiber conduction and synaptic transmission. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:617–628. doi: 10.1152/jn.00944.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safronov BV, Pinto V, Derkach VA. High-resolution single-cell imaging for functional studies in the whole brain and spinal cord and thick tissue blocks using light-emitting diode illumination. J Neurosci Meth. 2007;164:292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos SF, Melnick IV, Safronov BV. Selective postsynaptic inhibition of tonic-firing neurons in substantia gelatinosa by mu-opioid agonist. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1177–1183. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200411000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos SF, Rebelo S, Derkach VA, Safronov BV. Excitatory interneurons dominate sensory processing in the spinal substantia gelatinosa of rat. J Physiol. 2007;581:241–254. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura Y, Terui N, Hosoya Y. Difference in distribution of central terminals between visceral and somatic unmyelinated (C) primary afferent fibers. J Neurophysiol. 1989;62:834–840. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.4.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura Y, Terui N, Hosoya Y, Tonosaki Y, Nishiyama K, Honda T. Quantitative analysis of central terminal projections of visceral and somatic unmyelinated (C) primary afferent fibers in the guinea pig. J Comp Neurol. 1993;332:315–325. doi: 10.1002/cne.903320305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szentagothai J. Neuronal and synaptic arrangement in the substantia gelatinosa Rolandi. J Comp Neurol. 1964;122:219–239. doi: 10.1002/cne.901220207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Chiba T, Kurokawa M, Aoki Y. Dermatomes and the central organization of dermatomes and body surface regions in the spinal cord dorsal horn in rats. J Comp Neurol. 2003;462:29–41. doi: 10.1002/cne.10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Chiba T, Sameda H, Ohtori S, Kurokawa M, Moriya H. Organization of cutaneous ventrodorsal and rostrocaudal axial lines in the rat hindlimb and trunk in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2002;445:133–144. doi: 10.1002/cne.10158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd AJ, Koerber HR. Neuroanatomical substrates of spinal nociception. In: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, editors. Wall and Melzack's Textbook of Pain. 5th edn. Churchill Livingstone: Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Traub RJ, Mendell LM. The spinal projection of individual identified A-δ- and C-fibers. J Neurophysiol. 1988;59:41–55. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RJ, Sedivec MJ, Mendell LM. The rostral projection of small diameter primary afferents in Lissauer's tract. Brain Res. 1986;399:185–189. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell PJ, Lawson SN, McCarthy PW. Conduction velocity changes along the processes of rat primary sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 1989;30:577–584. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall PD. Do nerve impulses penetrate terminal arborizations? A pre-presynaptic control mechanism. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:99–103. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93883-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall PD, Bennett DL. Postsynaptic effects of long-range afferents in distant segments caudal to their entry point in rat spinal cord under the influence of picrotoxin or strychnine. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2703–2713. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.6.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis WD, Coggeshall RE. Sensory Mechanisms of the Spinal Cord. New York: Wiley; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Fitzgerald M. The properties of neurones recorded in the superficial dorsal horn of the rat spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1983;221:313–328. doi: 10.1002/cne.902210307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, King AE. Subthreshold components of the cutaneous mechanoreceptive fields of dorsal horn neurons in the rat lumbar spinal cord. J Neurophysiol. 1989;62:907–916. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.4.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]