Abstract

microRNAs play a critically important role in a wide array of biological processes including those implicated in cancer, neuro-degenerative and metabolic disorders, and viral infection. Although we have begun to understand microRNA biogenesis and function, experimental demonstration of their functional effects and the molecular mechanisms by which they function remains a challenge. Members of the let-7/miR-98 family play a critical role in cell cycle control with respect to differentiation and tumorigenesis. In this study, we show that exogenous addition of pre-let-7 in primary human fibroblasts results in a decrease in cell number and an increased fraction of cells in the G2/M cell cycle phase. Combining microarray techniques with DNA sequence analysis to identify potential let-7 targets, we discovered 838 genes with a let-7 binding site in their 3′-untranslated region that were down-regulated upon overexpression of let-7b. Among these genes is cdc34, the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme of the Skp1/cullin/F-box (SCF) complex. Cdc34 protein levels are strongly down-regulated by let-7 overexpression. Reporter assays demonstrated direct regulation of the cdc34 3′-untranslated region by let-7. We hypothesized that low Cdc34 levels would result in decreased SCF activity, stabilization of the SCF target Wee1, and G2/M accumulation. Consistent with this hypothesis, small interfering RNA-mediated down-regulation of Wee1 reversed the G2/M phenotype induced by let-7 overexpression. We conclude that Cdc34 is a functional target of let-7 and that let-7 induces down-regulation of Cdc34, stabilization of the Wee1 kinase, and an increased fraction of cells in G2/M in primary fibroblasts.

miRNAs2 are non-coding, single-stranded, conserved RNAs of ∼22 nucleotides that function as gene regulators (1). miRNAs have emerged as central post-transcriptional negative regulators and have been implicated in a wide array of biological processes including cell cycle control. In metazoans, individual miRNAs can down-regulate hundreds of mRNA targets by interacting with partially complementary sequences within their 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) (2, 3).

The let-7 miRNA was originally discovered in Caenorhabditis elegans as a switch gene induced as cells exit the cell cycle when C. elegans reach their adult stage (4). In humans and mouse, like C. elegans, the expression of let-7 is barely detectable in embryonic developmental stages but increases after differentiation and in mature tissue (5). let-7 family members have been implicated as tumor suppressors. Some of the 12 members of the let-7 family map onto genomic regions altered or deleted in human tumors (6, 7). Further, members of the let-7 family of miRNAs are consistently down-regulated in lung and colon cancer (8–10). In lung cancers, low levels of let-7 correlated with shorter survival after resection (9). Decreased let-7 levels in tumors are associated with elevated levels of Ras, which contains several let-7 binding sites within its 3′-UTR (8). let-7 expression is reduced in mammary progenitor cells (11) and breast cancer tumor-initiating cells (12), and enforced let-7 expression induces loss of self-renewing cells (11). During mammary epithelial cell differentiation, Ras affects self-renewal, whereas a different let-7 target, HMGA2, contributes to differentiation, thereby emphasizing the importance of identifying multiple miRNA targets to understand their functions (12). In this report, we draw attention to a novel let-7 target gene, Cdc34, and demonstrate a context in which it may play a functional role.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture, Antibodies, and Reagents—Human primary fibroblasts were maintained in FGM-2 (Hyclone, Thermo Fisher Scientific) or Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 100 μg/ml penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen). HEK293 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. Anti-Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (AbCam), anti-Cdc34 (H-81) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Wee1 (B11) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Cdc2-Tyr15-p (Cell Signaling Technology), and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG antibodies (GE Healthcare) were purchased.

Transfection and RNA Interference—Reverse transfection of fibroblasts was performed in 6-well plates. To prepare complexes, 50 nm pre- or anti-miR or negative control RNAs (Ambion) or siRNAs (see supplemental data) were combined with 4 μl of Oligofectamine transfection reagent (Invitrogen) and incubated in a total volume of 200μl of Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) at room temperature for 20 min. A trypsinized cell suspension was mixed with the Oligofectamine/RNA complex and plated (120,000 cells/well). After 24 h, the medium was changed to appropriate medium, and the samples were assayed at the indicated time points. Transfection was performed in duplicate, and the average and standard error of three independent experiments were calculated.

Alamar Blue Assay for Cell Viability/Proliferation—In 96-well plates, 5,000 cells/well were transfected with 50 nm pre- or anti-miR or negative control RNAs combined with 0.5 μl of Oligofectamine. After 4 h of incubation at 37 °C, growth medium plus serum for a final concentration of 10% was added. At the indicated time points, the percentage of Alamar blue (Invitrogen) reduced by the cells was determined according to the manufacturer's protocols. Transfection was performed in quadruplicate, and the average and standard error were calculated. Similar results were found by counting live cells by hemacytometry.

Flow Cytometry—Cells were trypsinized and fixed with 70% ethanol overnight at 4 °C. Cells were treated with 100 μg/ml RNase A (Roche Diagnostics) and 50 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma). Propidium iodide fluorescence was monitored with FACSCalibur flow cytometry (BD Biosciences). At least 20,000 cells were collected and analyzed with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Cell cycle distributions were calculated with ModFit LT software using the Watson Pragmatics algorithm.

Immunoblot Analysis—Total cellular protein was loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gels, electrophoresed, and electrotransferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Following electrotransfer, the membrane was blocked for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. Visualization of the protein signal was achieved with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare).

Luciferase Reporter Assay—For let-7 target validation, HEK293 cells were grown to a cell density of 60–70% in 24-well dishes and then transiently transfected with 0.5 μg of either experimental or control firefly luciferase plasmids, 0.5 μg of pRL-CMV (Renilla luciferase plasmid, Promega), and 50 nm pre-let-7 or a control pre-miR using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested, and luciferase activity was measured with a GloMaxTM 96 microplate luminometer (Promega). Transfection was performed in duplicate, and luciferase activity was measured in triplicate.

RESULTS

Pre-let-7b Transfection Results in a Decrease in Cell Proliferation and an Increased Fraction of Cells in G2/M Phase—let-7 is reduced in lung tumors as compared with adjacent normal tissue (9, 10, 13, 14). In primary fibroblasts, we observed an approximately two-thirds reduction in let-7b expression levels in dividing cells as compared with quiescent cells.3 To better understand the role of let-7 in the cell cycle of primary cells, we transfected asynchronously growing fibroblasts with miRNA precursor molecules for let-7b, let-7c, or a negative control. Fibroblasts transfected with pre-let-7b or pre-let-7c exhibited an inhibition of cell growth as compared with those transfected with the negative control at 72 and 96 h after transfection (Fig. 1A). Flow cytometry-based cell cycle analysis revealed a trend toward an accumulation of cells in G2/M in pre-let-7b-transfected primary fibroblasts (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that let-7 may play a central role in cell proliferation in normal primary fibroblasts.

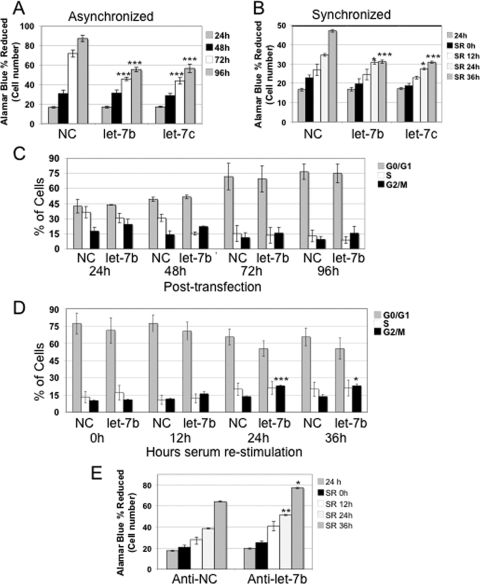

FIGURE 1.

High levels of let-7 results in reduced cell proliferation and G2/M arrest in asynchronously and synchronously dividing fibroblasts, whereas anti-let-7 results in increased proliferation. A and B, primary fibroblasts transfected with a negative control (NC) pre-miR, pre-let-7b, or pre-let-7c were monitored using Alamar blue at the indicated time points after transfection. The asterisks indicate statistical significance as compared with the negative control pre-miR. (*, = p < 0.05; **, = p < 0.01; ***, = p < 0.001). A, the addition of pre-let-7b or pre-let-7c resulted in fewer cells in asynchronously dividing primary fibroblasts at 72 and 96 h after transfection. B, cells were monitored at 24 h after transfection, at 36 h after serum withdrawal, then at 12, 24, and 36 h after serum stimulation. Transfection of let-7b or let-7c as compared with a negative control pre-miR resulted in fewer cells at 24 and 36 h after stimulation. C and D, cell cycle analysis of asynchronous (C) or synchronized (D) cells. An increase in the number of cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle was observed, which reached statistical significance in cells 24 and 36 h after serum stimulation. E, primary fibroblasts transfected with an anti-miR control or anti-let-7b were monitored with Alamar blue. Asterisks are as indicated in A and B. In synchronized cells, increased cell number was observed at 24 and 36 h after serum stimulation.

To further investigate the role of let-7 in cell cycle regulation, we monitored the cell cycle distribution of pre-let-7-transfected cells during synchronization by serum withdrawal and subsequent stimulation to re-enter the cell cycle. Transfection with pre-let-7b or another let-7 family member (pre-let-7c) led to a decrease in cell number as compared with cells transfected with control pre-miR (Fig. 1B). Moreover, cells with added pre-let-7b tended to accumulate in the G2/M phase after serum restimulation (p = 0.0004 and p = 0.015, at 24 and at 36 h, respectively) (Fig. 1D). Conversely, anti-let-7b, an RNA that acts as a competitive inhibitor of let-7b, caused a statistically significant increase in cell number as compared with a control anti-miR (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that let-7 causes a decrease in cell number and an increase in the fraction of cells in the G2/M phase.

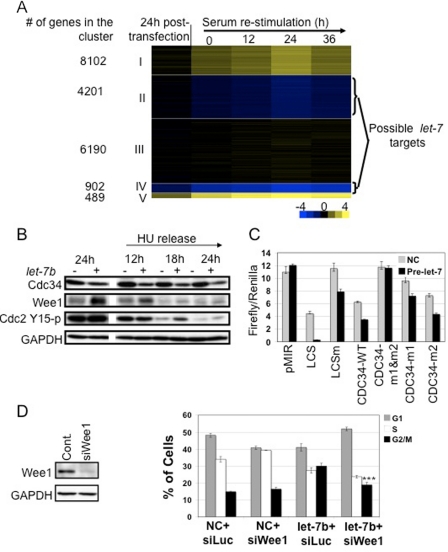

Microarray Analysis and Identification of Possible let-7 Targets—To gain greater insight into the specific genes targeted by let-7 that may cause the observed phenotypic effects on the cell cycle, we used microarrays to compare the global gene expression profiles of fibroblasts transfected with pre-let-7b with those transfected with a negative control as described above. At each time point, beginning at 24 h after transfection, cells transfected with a negative control pre-miR were compared with cells transfected with pre-let-7b (see supplemental data for details). Based on their expression profile, genes were clustered into five groups using the k-means clustering algorithm (Fig. 2A). The genes in clusters 2 and 4 were consistently down-regulated by pre-let-7b and showed moderate and strong down-regulation, respectively. Although the let-7 seed match (UACCUC) is present in the 3′-UTR of ∼16% of the clustered genes, it is present in 32% of genes in cluster 4 (p < 10–25) and in 18% of genes in cluster 2 (p ∼ 0.002) (Fig. 2A). These findings validate our assumption that bona fide let-7 targets can be identified by microarray (15, 16).

FIGURE 2.

Functional effects of let-7b overexpression. A, microarray analysis of gene transcript level changes associated with let-7b. Cells transfected with let-7 pre-miR or a negative control pre-miR were compared at 24 h after transfection, 36 h of serum withdrawal, and 12, 24, and 36 h of restimulation by hybridization to whole genome microarrays. The log2 of the ratio of expression in let-7b to negative control samples was used to cluster the genes using k-means clustering, and this ratio is shown with yellow indicating high expression in let-7b-transfected cells and blue indicating high expression in negative control cells. Genes in clusters 2 and 4 are consistently down-regulated upon pre-let-7b transfection, and some of these genes may be direct let-7 targets. B, pre-let-7 induction leads to down-regulation of Cdc34 protein levels in primary fibroblasts. Fibroblasts were transfected with pre-let-7b (+) or negative control pre-miR (–). Cells were synchronized by serum withdrawal (24 h) followed by hydroxyurea (HU) treatment (18 h), and then hydroxyurea was washed out to stimulate the cells to re-enter the cell cycle. Samples were taken at the indicated time points after serum stimulation. High levels of let-7b resulted in down-regulation of Cdc34 protein levels. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control. C, let-7 directly regulates the cdc34 3′-UTR through two let-7 recognition sites. Luciferase reporter constructs containing a mature LCS, a mutated let-7b (LCSm), the 3′-UTR of wild type cdc34 (CDC34-WT), or the cdc34 3′-UTR with mutations in the let-7 binding sites (CDC34-m1&m2, CDC34-m1, and CDC34-m2) were cloned downstream of a firefly luciferase reporter gene and transfected with pre-let-7b or negative control (NC) into HEK-293 cells. A second vector with a Renilla luciferase reporter was used for normalization of transfection efficiency. A mature LCS was used as a positive control. A portion of the cdc34 3′-UTR was sufficient to direct down-regulation of luciferase by endogenous and exogenous let-7. Mutating both of the let-7 recognition sites within the cdc34 3′-UTR was sufficient to abrogate the effect, demonstrating that these two sites are the functionally important sequences within the cdc34 3′-UTR. D, let-7b-mediated G2/M arrest is partially rescued by an siRNA to Wee1. Primary fibroblasts were transfected with an siRNA to Wee1 or left untreated (cont.) and analyzed by Western blot. Introduction of an siRNA to Wee1 resulted in reduced Wee1 levels 24 h after transfection (left). Asynchronously growing cells were transfected with negative control pre-miR or pre-let-7b and either an siRNA to luciferase (siLuc) or an siRNA to Wee1 (siWee1). Cells were collected 24 h after transfection and analyzed by flow cytometry for cell cycle (right). At 24 h after transfection, the siRNA to Wee1 resulted in an increase in the number of cells in S phase. Pre-let-7b-transfected cells contained a higher fraction of cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. In cells transfected with both pre-let-7b and an siRNA to Wee1, the S and G2/M fractions resembled those in control cells (NC + siLuc) (*** indicates G2/M fraction in let-7b + siLuc versus let-7b + siWee1, p < 0.001).

To identify potential let-7 targets, we looked for genes consistently down-regulated in the presence of let-7 (i.e. genes within cluster 2 or 4) that also contain at least one let-7 recognition site within their 3′-UTR, resulting in 838 genes (supplemental Table 1). The 838 genes within this list were enriched for 19 terms within the Gene Ontology data base at p < 10–4, including developmental process, protein localization, post-translational protein modification, and ubiquitin modification.

let-7 Negatively Regulates the E2 Ubiquitin-conjugating Enzyme Cdc34—We selected cdc34, a let-7 target that was strongly down-regulated with pre-let-7b transfection in our microarray experiments (Fig. 2A), for further analysis. Cdc34 is an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that targets multiple cell cycle regulators for proteasome-mediated degradation as part of the Skp1/cullin/F-box (SCF) complex (17). Thus, down-regulation of Cdc34 by let-7 is consistent with our finding that let-7 targets are enriched in gene products involved in the addition of ubiquitin to target proteins. Down-regulation of Cdc34 could be an important contributor to the cell cycle changes observed with pre-let-7b overexpression.

To assess the effects of pre-let-7b on Cdc34 protein levels, we transfected fibroblasts with pre-let-7b and then synchronized them by serum withdrawal followed by G1/S arrest by hydroxyurea. The hydroxyurea was then washed out, and the cells were stimulated to enter the cell cycle. Under these conditions, Cdc34 protein levels decreased with pre-let-7b transfection as compared with samples transfected with a negative control (Fig. 2B). By 24 h after transfection, Cdc34 protein levels had dropped significantly, and the levels continued to decline through 24 h of restimulation (Fig. 2B). In asynchronously growing cells, Cdc34 levels decreased with pre-let-7b transfection, and the levels continued to decline for 96 h after transfection (data not shown). As a control, we also monitored the levels of the previously reported let-7 target, Ras, using an antibody that recognizes both N-Ras and K-Ras and an antibody to N-Ras (8). Under both the asynchronous and the synchronous protocols, pre-let-7b transfection led to a larger and more rapid decrease in Cdc34 levels than in Ras protein levels. Cdc34 was also down-regulated by let-7b overexpression in A549 (lung) and HepG2 (liver) cancer cells (supplemental Fig. S2). Moreover, cdc34 is also down-regulated at the transcript level in A549 and HepG2 cells when let-7 is overexpressed (18).

To determine whether let-7 directly regulates cdc34 via recognition sites in its 3′-UTR, we established a luciferase reporter system. As positive controls, a firefly luciferase reporter vector containing the let-7b miRNA complementary sequence (LCS) and a vector with the let-7 complementary sequence containing let-7 seed mutations (Fig. 2C, LCSm) were generated from the pMIR-REPORT plasmid. As expected, firefly luciferase activity was reduced for LCS as compared with the pMIR-REPORT control empty vector, whereas the mutated version was less strongly regulated. Co-transfection of LCS with pre-let-7b resulted in further reduction of luciferase activity to background levels (Fig. 2C).

Having confirmed that the luciferase assay responds to let-7, we then tested reporters in which the 3′-UTR of cdc34 was inserted downstream of firefly luciferase. The 3′-UTR of cdc34 contains conserved let-7 seed matches at positions 27–33 (site 1) and 68–77 (site 2) (CDC34-WT). Reporters containing mutations in the let-7 seed at site 1 (CDC34-m1), site 2 (CDC34-m2), and both sites (CDC34-m1&m2) were also tested for luciferase reporter activity (Fig. 2C). Endogenous let-7 reduced luciferase activity in plasmids containing the CDC34 3′-UTR by about 40%. Transfection of a CDC34-m1&m2 vector resulted in luciferase activity at levels similar to the control plasmid in the presence or absence of exogenous let-7, demonstrating specific down-regulation of reporter activity by let-7 through the cdc34 3′-UTR. Luciferase activity from vectors with mutations in a single site revealed that both sites contribute to down-regulation of Cdc34 by let-7b and that site 1 results in stronger down-regulation than site 2.

Wee1 Partially Rescues let-7-mediated G2/M Arrest—Cdc34 controls progression into mitosis partially by degrading the Wee1 kinase, which adds inhibitory phosphates to cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdc2) (19). We hypothesized that let-7 overexpression may result in reduced Cdc34 levels and Wee1 stabilization. This would be expected to result in the increased number of cells in G2/M phase observed upon let-7b overexpression (Fig. 1, C and D) because Wee1 degradation in G2 is required for progression into mitosis (20). Anti-let-7b would result in reduced levels of Wee1 and is thus predicted to hasten the cell cycle and result in an increased proliferation rate (Fig. 1E). To test this hypothesis, we monitored Wee1 levels in let-7b-overexpressing cells. Primary fibroblasts were transfected with pre-let-7b or control pre-miRNA. Western blot analysis revealed higher Wee1 levels in cells transfected with pre-let-7b (Fig. 2B). Introduction of pre-let-7b into A549, but not HepG2 cancer cells, also resulted in Wee1 stabilization (supplemental Fig. S2). We then determined whether stabilization of Wee1 in pre-let-7b-transfected primary fibroblasts leads to elevated levels of the Wee1 substrate Cdc2-Tyr15-p. Western blot analysis using the phosphospecific Cdc2-Tyr15-p antibody detected a higher level of Cdc2-Tyr15-p in pre-let-7b-transfected cells (+) as compared with control pre-miR-transfected cells (–) (Fig. 2B).

To assess the functional effect of Wee1 stabilization, we transfected asynchronous fibroblasts with pre-let-7b or a negative control in the presence or absence of an siRNA to Wee1 or luciferase as a control. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the Wee1 siRNA resulted in reduced Wee1 levels (Fig. 2D, left) and an increased fraction of cells in S phase (Fig. 2D, right). Cells transfected with pre-let-7b exhibited a significant increase in the fraction of cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle as compared with cells transfected with a negative control (Fig. 2D). When cells were co-transfected with pre-let-7b and an siRNA to Wee1, the fractions of cells in S phase and in G2/M phase of the cell cycle were similar to the levels in cells transfected with the negative control (Fig. 2D). Thus, we bypass the let-7-mediated block by decreasing Weel levels. These results are consistent with a model in which let-7 induces G2/M arrest via down-regulation of Cdc34 and subsequent inhibition of Cdc2 via Wee1 stabilization.

DISCUSSION

Members of the let-7 miRNA family are induced under a variety of conditions in which cells exit the cell cycle and are down-regulated in the context of inappropriate proliferation. The let-7 miRNA was originally discovered in C. elegans as a switch gene induced as cells exit the cell cycle when C. elegans reach their adult stage (4). In humans and mouse, like C. elegans, the expression of let-7 is barely detectable in embryonic stages but increases after differentiation and in mature tissue (5). In contrast, let-7 is frequently underexpressed in lung tumors (9, 10, 13) and in colon cancer cell lines (7).

Overexpression of the let-7 miRNA contributes to exit from the proliferative cell cycle with the specific effects dependent upon cell type. In the A549 lung cancer cell line, let-7 overexpression suppresses proliferation (18) and reduces colony-forming capability (9), whereas inhibiting let-7 results in more cells (18). Similarly, transfection of let-7 into colorectal cancer cells causes a dose-dependent decrease in cell number and decreased plating efficiency (7). In HepG2 cells, introduction of let-7 results in an accumulation of cells in G0/G1 (18). In a mouse mammary epithelial cell line, let-7 overexpression induces loss of self-renewing cells from the population (11). We show here that introduction of pre-let-7 into normal fibroblasts leads to reduced cell number and to G2/M cell cycle arrest. Previous studies on the functional effects of let-7 have focused on the targets Ras, HMGA2, and c-Myc (8, 21–23). We show here that Cdc34, the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme of the SCF complex, is a direct let-7 target through Western blotting and reporter assays. The results demonstrate a mechanistic link between let-7 and proteasome-mediated protein degradation. Because many cell cycle proteins are targeted for ubiquitination and degradation by the SCF complex, cell type differences in the role of different direct or indirect let-7 cell cycle targets or in the targets of the SCF could result in the cell type specificity observed in the phenotypic consequences of regulating let-7 levels. In primary fibroblasts, we show that an increase in let-7 levels results in an increased fraction of cells in G2/M, and this phenotype correlates with stabilization of the SCF target, Wee1 kinase, as Cdc34 levels decline. In A549 and HepG2 cells, let-7 overexpression also leads to down-regulation of Cdc34, but in these cells, there is an accumulation of cells in G0/G1 phase (supplemental Fig. S2), similar to findings reported by Jonson et al. (18) for HepG2 cells. Different let-7 targets, or the same targets in different cellular environments, may contribute to the cell cycle phenotype in cancer cells. In A549 cells, Cdc34 down-regulation by let-7 overexpression resulted in Wee1 protein stabilization, suggesting that a similar regulatory mechanism may exist in some cancer cells. We hypothesize that, in some types of cancer cells, low let-7 levels may result in higher levels of Cdc34. This could cause faster proteolysis of cell cycle proteins, thus hastening cell cycle transitions and potentially contributing to the increased genomic instability of cancer cells. Indeed, future studies could test whether this represents part of the basis for the association between low let-7 levels and poor prognosis (9, 10).

Our findings suggest a mechanistic link between the let-7 family of miRNAs, G2/M arrest in primary fibroblasts, and the Cdc34-mediated proteolytic degradation of Wee1 kinase. We anticipate that unraveling the molecular mechanisms by which miRNAs mediate their effects will allow us to decipher the central regulatory role of miRNAs in many fundamental biological processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the following colleagues at Princeton University: Jessica Buckles, Donna Storton, Christina DeCoste, Curtis Huttenhower, Erin Haley, Jay Im, Peter Wei, John Matese, Yibin Kang, Manav Korpal, Amy Caudy, Leonid Kruglyak and the Coller laboratory.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM081686. This work was also supported in part by Grant 2007RSGl9572 from the PhRMA Foundation (to H. A. C.) and by National Institutes of Health Grant P50 GM071508 from the NIGMS Center of Excellence (to H. A. C., A. L. and S. T.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental text, two supplemental figures, and three supplemental tables.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: miRNA, microRNA; pre-miR, pre-miRNA; UTR, untranslated region; SCF, Skp1/cullin/F-box; siRNA, small interfering RNA; LCS, let-7b complementary site; E2, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme; WT, wild type.

A. Legesse-Miller and H. A. Coller, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Bartel, D. P. (2004) Cell 116 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis, B. P., Burge, C. B., and Bartel, D. P. (2005) Cell 120 15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim, L. P., Lau, N. C., Garrett-Engele, P., Grimson, A., Schelter, J. M., Castle, J., Bartel, D. P., Linsley, P. S., and Johnson, J. M. (2005) Nature 433 769–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reinhart, B. J., Slack, F. J., Basson, M., Pasquinelli, A. E., Bettinger, J. C., Rougvie, A. E., Horvitz, H. R., and Ruvkun, G. (2000) Nature 403 901–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee, Y. S., Kim, H. K., Chung, S., Kim, K. S., and Dutta, A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 16635–16641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calin, G. A., Sevignani, C., Dumitru, C. D., Hyslop, T., Noch, E., Yendamuri, S., Shimizu, M., Rattan, S., Bullrich, F., Negrini, M., and Croce, C. M. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 2999–3004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akao, Y., Nakagawa, Y., and Naoe, T. (2006) Biol. Pharm. Bull. 29 903–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson, S. M., Grosshans, H., Shingara, J., Byrom, M., Jarvis, R., Cheng, A., Labourier, E., Reinert, K. L., Brown, D., and Slack, F. J. (2005) Cell 120 635–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takamizawa, J., Konishi, H., Yanagisawa, K., Tomida, S., Osada, H., Endoh, H., Harano, T., Yatabe, Y., Nagino, M., Nimura, Y., Mitsudomi, T., and Takahashi, T. (2004) Cancer Res. 64 3753–3756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanaihara, N., Caplen, N., Bowman, E., Seike, M., Kumamoto, K., Yi, M., Stephens, R. M., Okamoto, A., Yokota, J., Tanaka, T., Calin, G. A., Liu, C. G., Croce, C. M., and Harris, C. C. (2006) Cancer Cell 9 189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibarra, I., Erlich, Y., Muthuswamy, S. K., Sachidanandam, R., and Hannon, G. J. (2007) Genes Dev. 21 3238–3243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu, F., Yao, H., Zhu, P., Zhang, X., Pan, Q., Gong, C., Huang, Y., Hu, X., Su, F., Lieberman, J., and Song, E. (2007) Cell 131 1109–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inamura, K., Togashi, Y., Nomura, K., Ninomiya, H., Hiramatsu, M., Satoh, Y., Okumura, S., Nakagawa, K., and Ishikawa, Y. (2007) Lung Cancer 58 392–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taipale, J., and Beachy, P. A. (2001) Nature 411 349–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baek, D., Villen, J., Shin, C., Camargo, F. D., Gygi, S. P., and Bartel, D. P. (2008) Nature 455 64–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selbach, M., Schwanhausser, B., Thierfelder, N., Fang, Z., Khanin, R., and Rajewsky, N. (2008) Nature 455 58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willems, A. R., Schwab, M., and Tyers, M. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1695 133–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson, C. D., Esquela-Kerscher, A., Stefani, G., Byrom, M., Kelnar, K., Ovcharenko, D., Wilson, M., Wang, X., Shelton, J., Shingara, J., Chin, L., Brown, D., and Slack, F. J. (2007) Cancer Res. 67 7713–7722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan, D. O. (1995) Nature 374 131–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michael, W. M., and Newport, J. (1998) Science 282 1886–1889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar, M. S., Lu, J., Mercer, K. L., Golub, T. R., and Jacks, T. (2007) Nat. Genet. 39 673–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayr, C., Hemann, M. T., and Bartel, D. P. (2007) Science 315 1576–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sampson, V. B., Rong, N. H., Han, J., Yang, Q., Aris, V., Soteropoulos, P., Petrelli, N. J., Dunn, S. P., and Krueger, L. J. (2007) Cancer Res. 67 9762–9770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.