Abstract

Phosphatidylcholine is the major phospholipid in eukaryotic cells. There are two main pathways for the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine: the CDP-choline pathway present in all eukaryotes and the phosphatidylethanolamine methylation pathway present in mammalian hepatocytes and some single celled eukaryotes, including the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In S. cerevisiae, the rate-determining step in the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine via the CDP-choline pathway is catalyzed by Pct1. Pct1 converts phosphocholine and CTP to CDP-choline and pyrophosphate. In this study, we determined that Pct1 is in the nucleoplasm and at endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear membranes. Pct1 directly interacts with the α-importin Kap60 via a bipartite basic region in Pct1, and this region of Pct1 was required for its entry into the nucleus. Pct1 also interacted with the β-importin Kap95 in cell extracts, implying a model whereby Pct1 interacts with Kap60 and Kap95 with this tripartite complex transiting the nuclear pore. Exclusion of Pct1 from the nucleus by elimination of its nuclear localization signal or by decreasing Kap60 function did not affect the level of phosphatidylcholine synthesis. Diminution of Kap95 function resulted in almost complete ablation of phosphatidylcholine synthesis under conditions where Pct1 was extranuclear. The β-importin Kap95 is a direct regulator membrane synthesis.

Phosphatidylcholine (PC)4 is the major lipid in eukaryotic cell membranes, comprising approximately half of the phospholipid content. PC is important for providing organellar and cellular impermeability barriers and has crucial functions in cells beyond this, since it serves as a source of numerous second messengers, including diacylglycerol for the activation of protein kinases, arachidonic acid for metabolism to prostaglandins and leukotrienes, and lysophosphatidylcholine to provide a chemotactic signal for lymphocytes and macrophages (1-4). The turnover of PC for the provision of signaling molecules must be integrated with increased PC synthesis to ensure that the biophysical roles of PC in membranes are maintained. An inability to synthesize PC at the required levels results in cell death (5-8).

PC is synthesized by two pathways, the CDP-choline pathway and the phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) methylation pathway. The PE methylation pathway is found in mammalian hepatocytes and in several single celled eukaryotes, including the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In both cases, it provides an alternate route for the synthesis of PC when dietary/external choline (the initial substrate of the CDP-choline pathway) is low (5, 6, 8, 9). The three-step CDP-choline pathway is present in essentially all eukaryotic cells and is initiated by the conversion of choline to phosphocholine by choline kinase (9-15). The conversion of phosphocholine to CDP-choline by CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase is the rate-determining step for PC synthesis and is encoded by the CCTα and -β genes in mammals (8, 16-27) and the PCT1 gene in yeast (8, 9). CDP-choline and diacylglycerol are substrates for cholinephosphotransferase, resulting in the synthesis of PC (28-32).

The rate-determining enzyme for PC synthesis, the CCTα isoform in most mammalian cells and Pct1 in S. cerevisiae, localizes to the nucleus (8, 16, 21, 33-36). This seems paradoxical, since the upstream and downstream enzymes in the CDP-choline pathway localize to the cytoplasm or are integrated into endoplasmic reticulum (ER)/Golgi membranes, respectively (14, 31). The molecular processes that result in CCTα/Pct1 localization to the nucleus are not known.

In this study, we demonstrate that the karyopherin Kap60 (Srp1/importin-α) interacts with Pct1. Kap60 and Kap95 (Rsl1/importin-β) form a heterodimer that regulates protein import into the nucleus (37-39). Diminution of the function of either Kap60 or Kap95 abolished Pct1 nuclear import. A bipartite basic region in Pct1 was required for Pct1 to interact with Kap60 and for its import into the nucleus. Deletion of the nuclear localization signal from Pct1 resulted in its localization to the cytoplasm but did not affect the level of PC synthesis. The rate of PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway was normal when Pct1 import into the nucleus was prevented by decreasing Kap60 function; however, diminishing Kap95 function resulted in almost complete ablation of PC synthesis via the CDP-choline pathway under conditions where Pct1 was extranuclear.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents—[methyl-14C]Choline chloride and [methyl-14C]methionine were from American Radiolabeled Chemicals. Affinity resins were purchased from Sigma (rabbit IgG-agarose), Stratagene (calmodulin-agarose), and Clontech (Talon). Complete and EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablets were purchased from Roche Applied Science, and leupeptin, pepstatin A, and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride were from Sigma. Antibodies used were anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) and anti-red fluorescent protein (RFP) (Clontech), anti-His6 (Novagen), anti-c-Myc and anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-linked IgG (Cell Signaling), and anti-TAP (Open Biosystems).

Yeast Strains and Plasmids—The yeast strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Tables 1 and 2. The pct1Δ::KanMx-containing strains were constructed by amplifying pct1Δ::KanMx from genomic DNA of pct1Δ::KanMx from the yeast gene deletion strain set (from Euroscarf) by PCR. Primers used hybridized 100 bp upstream of the start for the open reading frame and 100 bp downstream of the stop codon and were 5′-TACCCATTCCCCTTTCTTGCATACGCCAGTCACTTTTC-3′ and 5′-ATCTTTAAATATGTACATACGCTTGTTTATACGTGGAGGCG-3′. The linear PCR product was transformed into cells and G418-resistant transformants were selected and screened by PCR to verify the integration of the drug-resistant cassette into the PCT1 locus. We thank Tim Levine for the kind gift of the plasmid expressing Scs2-TM (transmembrane)-RFP.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Yeast strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| BY4741 | ahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Euroscarf |

| YPTAP | ahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 PCT1-TAP | Open Biosystems |

| Y14832P | α his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 pct1Δ::kanMx | This study |

| CMY214 | α mfa1::MFRA-pr-HIS3 can1Δ0 his3Δ0 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 lys2Δ0 pct1Δ::NatMx | This study |

| YCopRP | α his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 COP1-RFP [pGFP1] | This study |

| YSecRP | α his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 SEC13-RFP [pGFP1] | This study |

| YNicRP | α his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 NIC96-RFP [pGFP1] | This study |

| SWY1313 | aade2Δ1 can1Δ100 his3Δ11 leu2Δ3 trp1Δ1 ura3Δ1 kap95Δ::HIS3 | Jeremy Thorner; Ref. 39 |

| [pSW509/pRS315-kap95(L63A)ts] | ||

| SWY1313a | SWY1313 pct1Δ::kanMx | This study |

| SWY1313b | SWY1313a [pPct1b] | This study |

| SWY1313c | SWY1313a [pPct1-(76-424)b] | This study |

| SWY1313d | SWY1313a [pGFP1] | This study |

| NOY612 | aade2Δ1 can1Δ100 his3Δ1 leu2Δ3 trp1Δ1 ura3Δ0 kap60-31ts | Jeremy Thorner; Ref. 39 |

| NOY612a | NOY612 pct1Δ::kanMx | This study |

| NOY612b | NOY612a [pPct1a] | This study |

| CMY110 | α his3Δ1 ade2Δ1 leu2Δ3 cho2::LEU2 | This study |

| YCC9 | Y14832P [pCC9] | This study |

| YGFP1 | Y14832P [pGFP1] | This study |

| YGFP2 | Y14832P [pGFP2] | This study |

| YPCT1 | Y14832P [pPct1a] | This study |

| YNLS1 | Y14832P [pPct1-(56-424)] | This study |

| YNLS2 | Y14832P [pPct1-(76-424)] | This study |

| PJ69-4a | atrp1-901 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-200 gal4Δ gal80Δ LYS2::GAL1-HIS3 GAL2-ADE2met2::GAL7-lacZ | Stephen Elledge; Ref. 42 |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pRS413 | Yeast shuttle vector; HIS3 gene; low copy | Ref. 52 |

| pRS416 | Yeast shuttle vector; TRP1 gene; low copy | Ref. 52 |

| pRS423 | Yeast shuttle vector; HIS3 gene; high copy | Ref. 52 |

| pCC9 | pRS413 with HA-tagged PCT1 under control of own promoter | This study |

| pGFP1 | pRS413 with GFP-tagged PCT1 under control of own promoter | This study |

| pGFP1b | pRS416 with GFP-tagged PCT1 under control of own promoter | This study |

| pGFP2 | pRS423 with GFP-tagged PCT1 under control of own promoter | This study |

| pMM5 | pRS413 with PCT1 under control of own promoter | Ref. 8 |

| pESC-Trp | Galactose-inducible yeast expression vector with Myc epitope | Stratagene |

| pESC-His | Galactose-inducible yeast expression vector with Myc epitope | Stratagene |

| pET23b | Bacterial expression vector with His6 | Novagen |

| pPct1His6x | PCT1 ORF in frame with a C-terminal His6 tag in pET23b | This study |

| pPct1a | PCT1 ORF in frame with a C-terminal myc tag in pESC-His | This study |

| pPct1b | PCT1 ORF in frame with a C-terminal myc tag in pESC-Trp | This study |

| pPct1-(56-424) | PCT1 ORF lacking the codons for amino acid residues 2-55 in frame with a C-terminal Myc tag in pESC-His | This study |

| pPct1-(76-424)a | PCT1 ORF lacking the codons for amino acid residues 2-75 in frame with a C-terminal Myc tag in pESC-His | This study |

| pPct1-(76-424)b | PCT1 ORF lacking the codons for amino acid residues 2-75 in frame with a C-terminal Myc tag in pESC-Trp | This study |

| pAS1-CYH2 | Gal4 DNA binding domain two-hybrid plasmid | Ref. 42 |

| pACT2 | Gal4 activation domain two-hybrid plasmid | Ref. 42 |

| pGal4-BD-Pct1 | PCT1 ORF in pAS1-CYH2 | This study |

| pGal4-BD-Pct1ΔNLS | PCT1 ORF1 (lacking amino acid residues 2-75) in pAS-CYH2 | This study |

| pGal4-AD-Kap60 | KAP60 ORF in pACT2 | This study |

| pGal4-AD-Kap95 | KAP95 ORF in pACT2 | This study |

| pSE1112 | SNF1 in pAS1-CYH2 | Ref. 42 |

| pSE1111 | SNF4 in pACT2 | Ref. 42 |

Media—Rich medium was YEPD (1% bacto-yeast extract, 2% bacto-peptone, 2% dextrose). Minimal medium was SD (0.67% bacto-yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 2% dextrose) with 20 mg/liter adenine sulfate, 20 mg/liter l-histidine HCl, 100 mg/liter l-leucine, 30 mg/liter l-lysine, 20 mg/liter l-methionine, 20 mg/liter l-tryptophan, and 20 mg/liter uracil added as required, based on strain auxotrophies and plasmid maintenance. For expression of plasmids under control of a galactose-inducible promoter, dextrose was replaced with galactose.

Co-Purification of Pct1-TAP with Protein-binding Partners—A TAP tag protocol was followed as described with the following modifications (40, 41). Yeast strains containing genomic PCT1 plus or minus the TAP tag inserted at the 3′-end of the open reading frame were grown to midlog phase in 4 liters of YEPD at 25 °C. Cultures were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Pellets were resuspended in 10 mm K-Hepes, pH 7.9, 10 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science), and pepstatin A. Cells were lysed by passage through a French press three times at 8,000 p.s.i. The concentration of KCl was adjusted by adding one-ninth volume of 2 m KCl. Cell extract was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was added to IgG-agarose beads in IPP150 buffer (10 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40), incubated for 2 h at 4 °C, and eluted by gravity flow, and the beads were washed with 30 ml of IPP150 buffer and then with 10 ml of TEV cleavage buffer (10% glycerol, 10 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40/Triton X-100, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol). The beads were incubated with 1 ml of TEV cleavage buffer and 100 units of acTEV recombinant protease for 2 h at 16 °C. The eluate was recovered by gravity flow. Calmodulin beads washed with calmodulin binding buffer (10% glycerol, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm magnesium acetate, 1 mm imidazole, 2 mm CaCl2, 0.1% Nonidet P-40/Triton X-100) were added to the eluate along with 3 ml of calmodulin binding buffer and 3 μl of 1 m CaCl2. The suspension was incubated for 1 h at 4 °C, poured into a column, and washed with 30 ml of calmodulin binding buffer. Samples were eluted by gravity flow with 1 ml of calmodulin elution buffer (10% glycerol, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm magnesium acetate, 1 mm imidazole, 5 mm EGTA, 0.1% Nonidet P-40/Triton X-100). Samples were concentrated using a ReadyPrep Cleanup Kit (Bio-Rad). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and silver-stained, and bands were excised and analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Purification of Pct1-His6 and Determination of Protein Binding Partners—Pct1 expressed with a C-terminal His6 tag was purified from BL21(DE3) Escherichia coli cells as follows. Cells were grown in LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol to midlog phase at 37 °C. Protein expression was induced using 0.5 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, and cultures were transferred to 30 °C for 4 h. Cultures were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, cells were lysed using Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagent (B-Per; Pierce) containing EDTA-free complete protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science) by passage through 16.5-, 18.5-, 20-, 21.5-, and 23-gauge needles. The lysate was centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was added to Co2+ resin (Talon) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in wash buffer (50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 300 mm NaCl). Resin was pelleted and washed three times with 10 ml of wash buffer. Pct1-His6 was eluted using 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 300 mm NaCl, 150 mm imidazole. Pure Pct1-His6 was rebound to the Co2+ resin, and yeast cell protein extract was added to Pct1-His6-bound resin or empty resin for determination of Pct1-interacting proteins. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, Coomassie-stained, and excised for analysis by mass spectrometry.

Mass Spectrometry—Proteins contained in gel slices were reduced with dithiothreitol, carboxamidomethylated with iodoacetamide, and digested with trypsin. Peptides were extracted with 70% acetonitrile, 1% formic acid. The extraction solvent was removed under vacuum, and the tryptic peptides were resuspended in 5% methanol, 0.5% formic acid.

Liquid chromatography MS/MS was performed using an Ultimate pump and Famos autosampler (LC Packings, Amsterdam, Netherlands) interfaced to the nanoflow electrospray ionization source of a hybrid triple quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometer (QTrap; Applied Biosystems). Samples were injected onto a capillary column (0.10 × 150-mm Chromolith C18, monolithic; Merck) at a flow rate of 1.2 μl/min. Solvent A consisted of 98% water, 2% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid; Solvent B consisted of 2% water, 98% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid; and the linear gradient was as follows: 5% solvent B to 35% solvent B over 35 min and then 90% B for 6 min before re-equilibration at 5% solvent B. The sample was sprayed through distal coated fused silica emitter tips, 75-μm inner diameter with a 15-μm inner diameter tip (New Objectives PicoTip). The capillary voltage was 2.10 kV with a declustering potential of 60 V, and the curtain gas was set to 15 (arbitrary units). Spectra were acquired using the information-dependent acquisition mode. The two most intense ions from the survey scan (375-1200 m/z) were selected for tandem MS, and the collision energy was set based on the mass of the precursor as determined by the m/z and charge. The raw MS/MS data were searched against NCBI yeast entries and against all SwissProt entries using the MASCOT algorithm (Matrix Science). Search parameters were peptide mass and fragment mass tolerance of 0.8 and 0.5 Da, respectively, one missed cleavage allowed. Oxidized methionines and carboxamidomethylated cysteines were chosen as variable modifications.

Two-hybrid Interactions—The PCT1 open reading frame and the PCT1 open reading frame lacking its nuclear localization signal (without amino acid residues 2-75) were subcloned in frame with the Gal4 DNA binding domain (BD) in plasmid pAS1-CYH2. The open reading frames for KAP60 and KAP95 were subcloned in frame with the Gal4 DNA activation domain (AD) in plasmid pACT2. Plasmids were transformed into the reporter strain PJ69-4A (MATa trp1-901 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-200 gal4Δ gal80Δ LYS2::GAL1-HIS3 GAL2-ADE2 met2::GAL7-lacZ) and grown on SC medium lacking Trp and Leu to select for plasmids. Cells were patched onto medium lacking Trp, Leu, Ade, and His to determine two-hybrid interactions (42). SNF1 in frame with the Gal4 DNA binding domain and SNF4 in frame with the Gal4 activation domain were used as controls for nonspecific protein-protein interactions, as were empty vectors.

Microscopy—Cells were observed using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope fitted with a plan-neofluor 100[×] oil immersion lens. Images were captured using a Zeiss Axio Cam HR using Axiovision 4.5 software. Live cells were visualized using differential interference contrast, GFP, or rhodamine filters, as required. To visualize GFP and RFP fusion proteins in live cells, cells were grown to midlog phase at 30 °C and mounted on a 2% agarose pad. To counterstain for DNA, cells were incubated in 2 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 20 min before viewing. Strains expressing Pct1-Myc were visualized by immunofluorescence of formaldehyde-fixed cells in mounting medium that consisted of 90% glycerol, 10% phosphate-buffered saline, and DAPI. All primary antibodies were used at 1:1000 dilution. All secondary antibodies were used at 1:4000 dilution.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blot Analysis—Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE with 10% acrylamide or precast gradient 4-20% gels (Bio-Rad) for mass spectrometry samples. Gels were stained with Coomassie Blue or silver nitrate. Proteins separated on gels for Western blot analysis were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and detected using appropriate primary and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Metabolic Labeling—For PC synthesis through the CDP-choline or methylation pathways, 10 μm [14C]choline or [methyl-14C]methionine was added, respectively. Cells were grown to midlog phase at 25 °C (a portion was shifted to 37 °C for 1 h when analyzing kap60ts and kap95ts temperature-sensitive alleles), and radiolabel was added to the cultures for 1 h. Cells expressing proteins with a galactose-inducible promoter were shifted to galactose-containing medium for 2-3 h to induce expression of Pct1 before radiolabel was added. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 3,500 rpm for 5 min in a tabletop centrifuge, and lipids were extracted using the method of Folch, as described (8, 9). The organic phase contained PC. Analysis of aqueous phase choline-containing metabolites was as follows. The aqueous phase was dried down overnight using vacuum and resuspended in distilled water. Samples were spotted on Silica Gel G plates (Analtech) and developed using a solvent of 50 ml of methanol, 50 ml of 0.6% NaCl, and 5 ml of NH4OH. The plate was dried and analyzed for radiolabel distribution using a BioScan radiometric detector. Radioactive bands were scraped into vials, and radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting.

RESULTS

Identification of Kap95 and Kap60 as Potential Pct1-interacting Proteins—Proteins that directly bind to Pct1 or its mammalian homologue CCTα have yet to be identified. This is a major obstacle in determining the mechanisms regulating PC synthesis and its integration with other cell biological processes. Our strategy for identification of potential Pct1-interacting proteins was to use two different methods to identify Pct1-protein interactions. Proteins identified using both protocols were considered further.

In the first approach, Pct1 containing a C-terminal Pct1-TAP tag inserted at the 3′-end of the PCT1 open reading frame, allowing for expression of PCT1 from within the genome and under control of its own promoter, was used. Pct1-TAP was expressed full-length and was biologically active (Fig. S1). This in vivo approach was supplemented by a second in vitro procedure whereby proteins from yeast extract were identified that bound to pure Pct1 protein (Fig. S2). The identity of Pct1-binding proteins was determined by electrospray ionization-MS/MS and querying the raw MS/MS data against both NCBI yeast entries and all SwissProt entries (Tables S1 and S2). The karyopherin Kap95 was identified in both the in vivo and in vitro Pct1-protein interaction protocols. Kap95 is one of several β-importins that regulate transport of proteins through the nuclear pore. Cargo proteins that use Kap95 to enter the nucleus typically first bind to the α-importin Kap60, and we had identified Kap60 as a potential Pct1-interacting partner in the Pct1-TAP study. Upon binding of Kap60 to the target protein, Kap95 is recruited, and the tripartite Kap60-Kap95-target protein complex traverses the nuclear pore and enters the nucleus (37-39, 43).

Analysis of Pct1, Kap60, and Kap95 Protein-Protein Interactions and Determination of the Region of Pct1 Required for Nuclear Localization—Kap60 normally binds proteins through a highly basic stretch within their N terminus, resulting in the recruitment of Kap95 and formation of a heterotrimer that facilitates nuclear import (37, 43). Pct1 possesses two highly basic regions at its N terminus, 25KKNKNKR31 and 60PRKRRRL66. To determine whether these basic stretches are required for Pct1 interaction with Kap60 or Kap95, a two-hybrid protein-protein interaction assay was performed. Cells containing full-length Gal4-BD-Pct1 and Gal4-AD-Kap60 grew robustly (as did cells transformed with the Gal4-BD-Snf1 and Gal4-AD-Snf4 as positive controls), indicating Pct1 interacts with Kap60 (Table 3). Cells expressing Gal4-BD-Pct1-(76-424) and Gal4-AD-Kap60 did not grow, implying that amino acids within 1-75 of Pct1 interact with Kap60. Cells expressing Gal4-AD-Kap95 grew slowly in general, making two-hybrid analysis of Kap95 protein-protein interactions difficult to interpret.

TABLE 3.

Two-hybrid analysis of Pct1-protein interactions

| Gal4-BD fusion | Gal4-AD fusion | Growth on medium lacking histidine and adenine |

|---|---|---|

| Pct1 | Kap60 | +++ |

| Pct1 | Snf4 | − |

| Pct1 | Empty vector | − |

| Pct1-(76-424) | Kap60 | − |

| Pct1-(76-424) | Snf4 | − |

| Pct1-(76-424) | Empty vector | − |

| Snf1 | Kap60 | − |

| Snf1 | Snf4 | +++ |

| Snf1 | Empty vector | +/− |

| Empty vector | Kap60 | − |

| Empty vector | Snf4 | − |

| Empty vector | Empty vector | − |

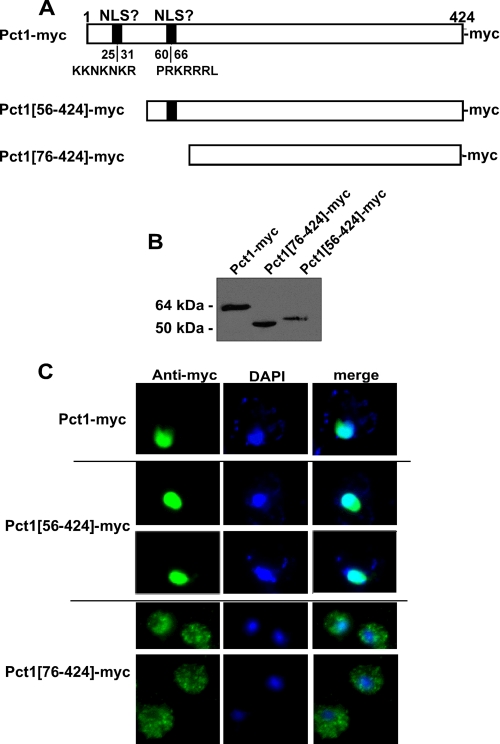

To determine if the N terminus of Pct1 (containing the basic stretches 25KKNKNKR31 and 60PRKRRRL66) was required for Pct1 nuclear localization, plasmids expressing Pct1 with a C-terminal Myc epitope (GAL-Pct1-Myc; this plasmid was previously demonstrated to produce a functional full-length Pct1-Myc that localizes to the nucleus) (8) or with N-terminal deletions eliminating either the first basic stretch Pct1-(56-424) or both basic stretches of Pct1-(76-424) under control of a galactose-inducible promoter were constructed (Fig. 1A). Western blot analysis using antibodies to the Myc epitope indicated that each protein was expressed at the expected molecular weight (Fig. 1B). Pct1-(56-424) localized to the nucleus in a manner similar to wild type Pct1, whereas Pct1-(76-424) was extranuclear (Fig. 1C). The NLS for Pct1 is contained within the first 76 amino acid residues of its N terminus.

FIGURE 1.

Pct1 contains a nuclear localization signal. A, deletion constructs of the PCT1 open reading frame were subcloned in frame with a C-terminal Myc tag and under control of the galactose-inducible promoter GAL1. B, plasmids expressing Pct1, Pct1-(56-424), and Pct1-(76-424) were transformed into pct1Δ cells and grown to midlog phase, and expression of Pct1-Myc was induced by the addition of galactose for 2 h. Protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot using an antibody against the Myc tag in total cell extracts. C, cells were visualized through immunofluorescence microscopy using an antibody against the Myc tag, and localization was analyzed versus the nuclear stain DAPI. Representative images are shown from three separate experiments where at least 100 cells/experiment were visualized.

The β-Importin Kap95 and the α-Importin Kap60 Are Required for Pct1 Nuclear Import—Pct1 was expressed from its endogenous promoter in frame with GFP from low and high copy plasmids. The Pct1-GFP expression plasmids, along with plasmids expressing untagged Pct1 or empty vector, were transformed into a strain with an inactivated PCT1 gene to allow for the analysis of the expressed proteins in the absence of endogenous Pct1. A Western blot using antibodies that recognize GFP detected one protein of the expected molecular weight of Pct1-GFP in cells expressing Pct1-GFP but not in cells expressing untagged Pct1 (Fig. S3). The Pct1-GFP was functional as determined by PC synthesis monitored via metabolic labeling with [14C]choline (Fig. S3). The Pct1-GFP protein fusion was expressed full-length and was active, indicating that GFP fluorescence would be an accurate reporter of Pct1 localization.

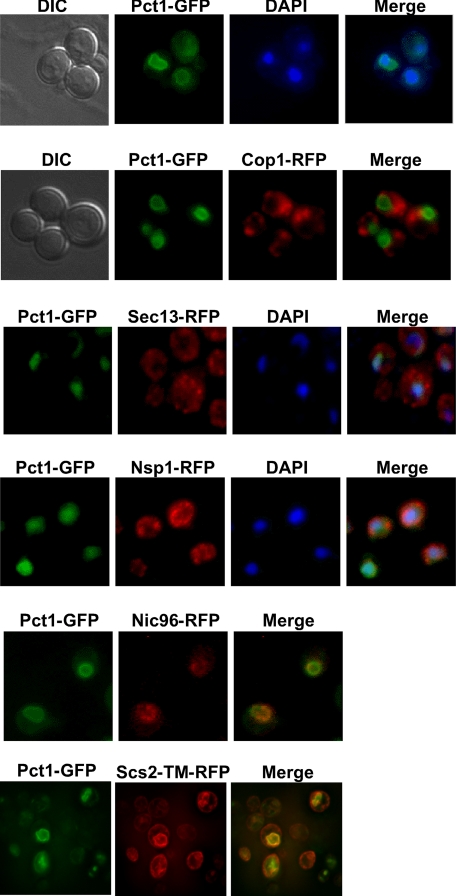

Pct1-GFP was found primarily in the nucleoplasm, as demonstrated by co-localization with the DNA-binding dye DAPI (Fig. 2). Although the bulk of Pct1-GFP co-localized with DAPI, there was a distinct ring of Pct1-GFP external to DAPI. Since Pct1 is an amphitropic enzyme whose translocation to membranes correlates with increased activity, this structure most likely represents the presence of Pct1-GFP on an organellar membrane. Pct1-GFP on a low copy plasmid was transformed into yeast strains expressing RFP-tagged organellar markers. Membrane-associated Pct1-GFP mainly co-localized with the ER marker Scs2-TM-RFP (the transmembrane domain of Scs2) (44) in the perinuclear ER but not with Scs2-TM-RFP at the cortical ER. Pct1-GFP partially colocalized with both Nic96-RFP (nuclear membrane marker) and Nsp1-RFP (nuclear pore complex marker), suggesting that Pct1 binds to perinuclear ER and nuclear membranes. Pct1 did not colocalize with markers for Cop I vesicles (Cop1-RFP) or Cop II vesicles (Sec13-RFP).

FIGURE 2.

Pct1 associates with endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear membranes. Pct1-GFP expressed from a low copy plasmid was grown to midlog phase, and live cells were visualized with differential interference contrast and by fluorescence microscopy and merged with organellar marker images: DAPI (nucleus); Nic96-RFP (nuclear membrane); Nsp1 (nuclear pore complex); Cop1-RFP (early Golgi and Cop I vesicles); Sec13-RFP (COP-II vesicles); Scs2-TM-RFP (ER). Representative images are shown from three separate experiments where at least 100 cells/experiment were visualized.

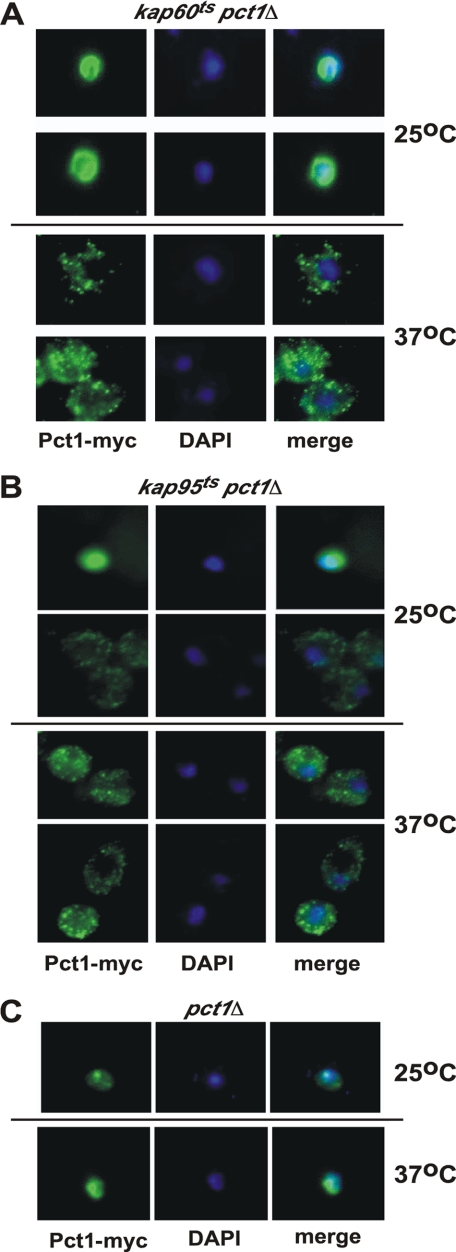

To determine the role of Kap60 and Kap95 in mediating Pct1 entry into the nucleus, we employed yeast strains harboring temperature-sensitive alleles of the KAP60 and KAP95 genes. The PCT1 gene was disrupted in kap60ts and kap95ts strains, and the resulting kap60ts pct1Δ and kap95ts pct1Δ strains were transformed with the plasmid containing the open reading frame of PCT1 under control of a galactose-inducible promoter with a Myc tag at the C terminus of Pct1 (GAL-Pct1-Myc).

The kap60ts pct1Δ strain harboring the GAL-Pct1-Myc plasmid was grown in glucose-containing medium to repress transcription of GAL-Pct1-Myc. Cells were grown to midlog phase at 25 °C, the permissive temperature for function of the kap60ts allele, and half of the cells were then shifted to 37 °C to inactivate Kap60 function. Expression of Pct1-Myc was then induced in both the 25 and 37 °C cultures by switching from glucose- to galactose-containing medium. Pct1-Myc localized to the nucleus in cells grown at the permissive temperature for the kap60ts allele and was extranuclear in cells grown at the non-permissive temperature (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Nuclear import of Pct1 requires the α-importin Kap60 and the β-importin Kap95. A, the yeast strain kap60ts pct1Δ transformed with the plasmid GAL-Pct1-Myc was grown to midlog phase at 25 °C, and a portion was shifted to 37 °C for 1 h. Expression of Pct1-Myc was induced by the addition of galactose for 2 h. Cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy using an antibody against the Myc tag and DAPI as a nuclear stain. B, strain kap95ts pct1Δ transformed with the plasmid GAL-Pct1-Myc grown and analyzed as per kap60ts pct1Δ cells. C, the pct1Δ strain carrying the plasmid GAL-Pct1-Myc was grown and analyzed as per A and B. Experiments were performed three times with >100 cells viewed per experiment. Representative images are shown.

The kap95ts pct1Δ strain containing the GAL-Pct1-Myc plasmid was subjected to a similar protocol as the kap60ts pct1Δ strain. At 25 °C, there was a mixed population of Pct1-Myc localized in the nucleus and outside the nucleus (Fig. 3B). This is in agreement with previous work with this kap95ts allele that demonstrated the activity of the encoded Kap95 was partly reduced even at 25 °C (39). Upon shifting cells to 37 °C, the nonpermissive temperature for the kap95ts allele, Pct1-Myc was entirely outside the nucleus.

To determine if increasing the growth temperature to 37 °C in and of itself affected Pct1 localization, the GAL-Pct1-Myc plasmid was transformed into the pct1Δ yeast strain, and the cells were subjected to the above protocol. Pct1-Myc was localized to the nucleus at both 25 and 37 °C (Fig. 3C), indicating that increased growth temperature does not result in exit of Pct1-Myc from the nucleus. There was no fluorescent signal in cells transformed with plasmids expressing Pct1 lacking the Myc tag or in cells treated with only secondary antibody, indicating that the fluorescent signal was due to expression of the Pct1-Myc protein (data not shown). Kap60 and Kap95 are required for nuclear import of Pct1.

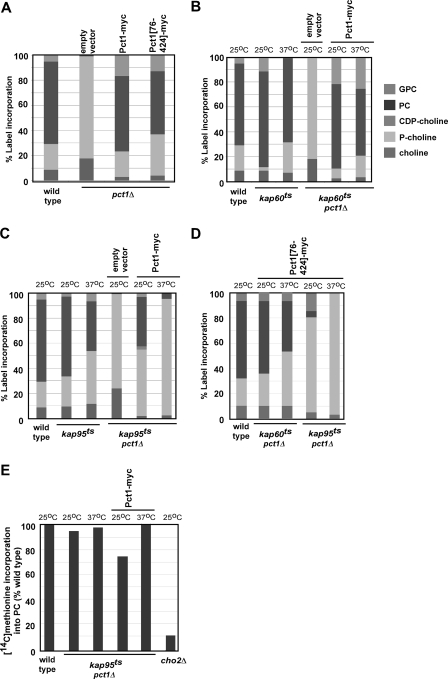

Kap95 Regulates PC Synthesis—To determine if Pct1 can reconstitute the CDP-choline pathway for PC synthesis when extranuclear, plasmids expressing wild type Pct1 and Pct1-(76-424) (lacking its NLS) were transformed into pct1Δ cells. Cells were grown to midlog phase, and expression of Pct1-myc and Pct1-(76-424)-Myc was induced by growth of cells in galactose-containing medium. Subsequently, [14C]choline was added to the medium, and its incorporation into CDP-choline pathway metabolites and PC was determined. Cells expressing Pct1 lacking its NLS synthesized PC at a level that was ∼75% that of cells expressing wild type Pct1 (Fig. 4A). PC can be synthesized if Pct1 is excluded from the nucleus by removal of its NLS, albeit at a slightly reduced level.

FIGURE 4.

Requirement of Kap60 and Kap95 for PC synthesis. A, wild type cells and pct1Δ cells containing empty vector or plasmids with wild type Pct1 (GAL-Pct1-Myc) or Pct1 lacking its NLS (GAL-Pct1-(76-424)-Myc) under control of a galactose-inducible promoter were grown to midlog phase at 30 °C in glucose, and expression of plasmid-borne Pct1 was induced by changing the carbon source to galactose for 2 h. This was followed by the addition of [14C]choline for 1 h, and its incorporation into CDP-choline pathway metabolites and PC was analyzed. B, wild type cells, kap60ts cells (containing the endogenous PCT1 gene), and the kap60ts pct1Δ cells transformed with empty vector or with the plasmid GAL-Pct1-Myc were grown to midlog phase at 25 °C, and a portion was shifted to 37 °C for 1 h. Expression of Pct1-Myc was induced by the addition of galactose for 2 h. Cells were labeled with [14C]choline for 1 h, and its incorporation into CDP-choline pathway metabolites and PC was analyzed. C and D, wild type cells, kap95ts cells (containing the endogenous PCT1 gene), and kap95ts pct1Δ cells transformed with empty vector or with a plasmid GAL-Pct1-Myc (C) or GAL-Pct1-(76-424)-Myc (D) were grown to midlog phase at 25 °C, and a portion was shifted to 37 °C for 1 h. Expression of Pct1-Myc was induced by the addition of galactose for 2 h. Cells were labeled with [14C]choline for 1 h, and its incorporation into CDP-choline pathway metabolites and PC was analyzed. E, wild type, cho2Δ (lacking the first enzyme in the PE → PC methylation pathway), and kap95ts pct1Δ cells transformed with empty vector or GAL-Pct1-Myc were grown as above, except that cells were labeled with [methyl-14C]methionine for 1 h, and its incorporation into PC was determined. All results represent the mean of three separate experiments performed in duplicate. S.E. was <15% for each. GPC, glycerophosphocholine; CDP-choline, cytidine 5′-diphosphocholine; P-choline, phosphocholine.

We next examined the role of Kap60 and Kap95 in PC synthesis. Wild type, kap60ts, and kap95ts cells were grown to mid-log phase at 25 °C, and half of each culture was shifted to 37 °C for 3 h to inactivate Kap60 or Kap95 function prior to the addition of [14C]choline for 1 h. Under these conditions, the localization of Pct1 was similar to that observed in wild type cells, as determined by monitoring localization of Pct1-GFP (in the nucleoplasm and associated with perinuclear ER and nuclear membranes; data not shown). In kap60ts cells, the rate of PC synthesis was similar to wild type at both 25 and 37 °C, whereas in kap95ts cells, there was a 50% decrease in the rate of PC synthesis at 37 °C (Fig. 4, B and C, three bars on the left). Loss of function of Kap95 results in a reduction in the synthesis of PC.

We also analyzed PC synthesis in cells lacking Kap60 or Kap95 function when Pct1 was excluded from the nucleus. The kap60ts pct1Δ and kap95ts pct1Δ cells were transformed with the GAL-Pct1-Myc plasmid and grown to midlog phase at 25 °C, and half of the culture was shifted to 37 °C to inactivate Kap60 or Kap95 function. Cells were then shifted to galactose-containing medium to induce production of Pct1 prior to the addition of [14C]choline. When Pct1 was excluded from the nucleus due to inactivation of Kap60, there was a small, ∼15%, decrease in PC synthesis (Fig. 4B, three bars on the right). Some Pct1 is excluded from the nucleus at 25 °C in cells containing the kap95ts allele (Fig. 3B), since this is a semipermissive temperature for function of this allele, and there was a 50% decrease in PC synthesis at this temperature. When Pct1 was excluded from the nucleus due to inactivation of Kap95 at 37 °C, PC synthesis was reduced to a level approaching that observed in cells with an inactivated PCT1 gene, with a concomitant increase in label in phosphocholine, the substrate for Pct1 (Fig. 4C, three bars on the right). Exclusion of Pct1 from the nucleus by inactivation of Kap95 prevented PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway at the Pct1-catalyzed step.

Pct1 can be excluded from the nucleus by removal of its NLS or by inactivation of Kap60 or Kap95. Inactivation of Kap95 resulted in a 50% decrease in PC synthesis when Pct1 was essentially endogenously localized and an almost complete ablation of PC synthesis when Pct1 was excluded from the nucleus.

Kap60 binds directly to Pct1 through the N-terminal region of Pct1 that is required for Pct1 entry into the nucleus. To assess a role for this interaction in regulation of PC synthesis, the same [14C]choline labeling protocol as above was used in kap60ts pct1Δ and kap95ts pct1Δ cells expressing Pct1-(76-424)-Myc (lacking its NLS) under control of a galactose-inducible promoter. At 25 °C, the permissive temperature for the kap60ts allele PC synthesis was modestly reduced compared with wild type, whereas at the nonpermissive temperature of 37 °C, PC synthesis was ∼50% that of wild type (Fig. 4D). At 25 °C, a semi-permissive temperature for function of the kap95ts allele, PC synthesis was reduced to ∼20% of that of wild type, and growth at 37 °C to eliminate all Kap95 function resulted in no detectable synthesis of PC. Radiolabel accumulated in phosphocholine, the substrate for Pct1. Preventing the interaction between Kap60 and Pct1 resulted in a more drastic inhibition of Pct1 activity, especially in the absence of functional Kap95.

To determine if the inability to synthesize PC through the CDP-choline pathway observed in kap95ts incubated at 37 °C was due to a general decrease in metabolic capacity after growth of these strains at 37 °C, we monitored flux through the second pathway for PC synthesis, the PE methylation pathway. Cells were labeled with [methyl-14C]methionine, and the incorporation of the label into PC was analyzed under identical growth conditions used to monitor [14C]choline incorporation. The kap95ts pct1Δ cells (with or without the GAL-Pct1-Myc plasmid) synthesized PC via PE methylation at levels similar to wild type cells at both 25 °C and 37 °C (Fig. 4E). Inactivation of Kap95 function does not render cells metabolically inefficient.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we determined that Pct1, the rate-determining enzyme in the CDP-choline pathway for the synthesis of the major membrane lipid PC, directly interacts with the α-importin Kap60. The N terminus of Pct1 was required for Pct1 to interact with Kap60 and for Pct1 to enter the nucleus. Pct1 was found to associate with both Kap60 and Kap95 in protein pull-down experiments from yeast cell lysate, and diminution of either Kap60 or Kap95 function prevented Pct1 from entering the nucleus. Pct1 probably enters the nucleus via the canonical route of binding the α-importin Kap60 through the N-terminal basic amino acid NLS on Pct1, followed by recruitment of the β-importin Kap95, with the tripartite protein complex being recognized by the nuclear pore for transport into the nucleus.

Decreasing Kap95 function substantially reduced PC synthesis; this was most prevalent when Pct1 was excluded from the nucleus. Deletion of the region of Pct1 that interacts with Kap60 exacerbated the inhibition of PC synthesis. As far as we are aware, this is the first instance of these importins directly regulating a metabolic pathway. Pure Pct1 protein possesses enzyme activity in vitro (45), and thus Kap60 or Kap95 are not required for enzymatic activity per se; however, in the context of the whole cell, Kap95 in particular is required for Pct1 activity. Two scenarios could be imagined in this regard: (i) Kap95 activates Pct1 in the context of the cell, or (ii) in the absence of Kap95 Pct1 is inhibited by some other cellular protein. Prior to nuclear import, Kap95 would be bound to Pct1 along with Kap60. Upon entering the nucleus, Kap60 and Kap95 dissociate from their target proteins, after which Kap60 and Kap95 are shuttled back out of the nucleus to facilitate further rounds of nuclear import. This may explain the specificity of Kap60 and Kap95 for regulation of Pct1 function when Pct1 is extranuclear.

The ultimate step in the synthesis of PC via the CDP-choline pathway is catalyzed by ER/Golgi-associated cholinephosphotransferases (29-31), and thus positioning Pct1 at the ER would be expected to allow for more efficient synthesis of PC by the CDP-choline pathway. Reports have delineated roles for both extranuclear and intranuclear Pct1. Exit from G0 to the G1 phase of the cell cycle was associated with an increase in PC synthesis and translocation of the mammalian homologue of Pct1, CCT1α, from the nucleus to the ER in Chinese hamster ovary cells (36). This is consistent with ER association of Pct1 supplying substrate when there is a demand for membrane synthesis to facilitate cell growth.

Export of the Drosophila homologues of Pct1, Cct1 and -2, from the nucleus to lipid droplets in the cytoplasm was observed upon treatment of cells with the fatty acid oleate (46). Lipid droplets contain a core rich in triacylglycerol covered by a monolayer of PC. Diminution of Drosophila Cct protein levels resulted in larger yet fewer lipid droplets. It is thought that translocation of Cct from the nucleus to lipid droplets when faced with excess fatty acid is required to provide PC to cover the extra surface area when lipid droplet synthesis is increased. Thus, it appears that that rate-determining step in PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway can associate with multiple extranuclear membranes to fulfill PC metabolizing needs of the cells. Although membrane binding of the rate-determining enzyme in the synthesis of PC is enhanced when membranes are loosely packed (19, 27, 47-51), the precise mechanisms regulating association with disparate membranes are not known and need to be determined.

Within the nucleus, mammalian CCTα has been demonstrated to regulate nucleoplasmic reticulum expansion. CCTα promotes formation of the nucleoplasmic reticulum, a nuclear membrane network of invaginations implicated in providing a scaffold for intranuclear signaling events, by affecting membrane tubulation (16, 21). Interestingly, this is via a mechanism independent of its catalytic activity and instead was facilitated by the membrane binding domain of CCTα.

The current study has determined the mechanism by which Pct1 enters the nucleus. Pct1 directly binds the α-importin Kap60, and together they form a complex with the β-importin Kap95 to allow for transit of Pct1 through the nuclear pore. Kap60 and, to a greater extent, Kap95 facilitate PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway at the Pct1-catalyzed step independent of their roles in nuclear import. Future work will focus on precisely how Kap60 and Kap95 affect Pct1 activity in the cell, determining roles for Pct1 in the nucleus beyond that of facilitating PC synthesis, and whether Pct1 can exit the nucleus once imported.

Supplementary Material

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1-S3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; TAP, tandem affinity purification; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; BD, DNA binding domain of Gal4; AD, activation domain of Gal4; GFP, green fluorescent protein; RFP, red fluorescent protein; MS, mass spectrometry; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; ORF, open reading frame; NLS, nuclear localization signal.

References

- 1.McMaster, C. R., and Jackson, T. R. (2004) in Topics in Current Genetics: Lipid Metabolism and Membrane Biogenesis (Daum, G., ed) pp. 5-88, Springer-Verlag, Berlin

- 2.Newton, A. C. (2004) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 25 175-177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serhan, C. N., Yacoubian, S., and Yang, R. (2008) Annu. Rev. Pathol. 3 279-312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peter, C., Waibel, M., Radu, C. G., Yang, L. V., Witte, O. N., Schulze-Osthoff, K., Wesselborg, S., and Lauber, K. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 5296-5305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boumann, H. A., Damen, M. J., Versluis, C., Heck, A. J., de Kruijff, B., and de Kroon, A. I. (2003) Biochemistry 42 3054-3059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boumann, H. A., Gubbens, J., Koorengevel, M. C., Oh, C. S., Martin, C. E., Heck, A. J., Patton-Vogt, J., Henry, S. A., de Kruijff, B., and de Kroon, A. I. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17 1006-1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cui, Z., Houweling, M., Chen, M. H., Record, M., Chap, H., Vance, D. E., and Terce, F. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 14668-14671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howe, A. G., Zaremberg, V., and McMaster, C. R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 44100-44107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMaster, C. R., and Bell, R. M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 14776-14783 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu, G., Aoyama, C., Young, S. G., and Vance, D. E. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 1456-1462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soto, A., and Carman, G. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 10079-10088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sher, R. B., Aoyoma, C., Huebsch, K. A., Ji, S., Kerner, J., Yang, Y., Frankel, W. N., Hoppel, C. L., Wood, P. A., Vance, D. E., and Cox, G. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 4938-4948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu, Y., Sreenivas, A., Ostrander, D. B., and Carman, G. M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 34978-34986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aoyama, C., Yamazaki, N., Terada, H., and Ishidate, K. (2000) J. Lipid Res. 41 452-464 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, K. H., and Carman, G. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 9531-9538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gehrig, K., Cornell, R. B., and Ridgway, N. D. (2008) Mol. Biol. Cell 19 237-247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sriburi, R., Bommiasamy, H., Buldak, G. L., Robbins, G. R., Frank, M., Jackowski, S., and Brewer, J. W. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 7024-7034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, L., Magdaleno, S., Tabas, I., and Jackowski, S. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 3357-3363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taneva, S. G., Patty, P. J., Frisken, B. J., and Cornell, R. B. (2005) Biochemistry 44 9382-9393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lagace, T. A., and Ridgway, N. D. (2005) Biochem. J. 392 449-456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagace, T. A., and Ridgway, N. D. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16 1120-1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackowski, S., and Fagone, P. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 853-856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bogan, M. J., Agnes, G. R., Pio, F., and Cornell, R. B. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 19613-19624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karim, M., Jackson, P., and Jackowski, S. (2003) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1633 1-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banchio, C., Schang, L. M., and Vance, D. E. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 32457-32464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cornell, R. B., and Northwood, I. C. (2000) Trends Biochem. Sci. 25 441-447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Attard, G. S., Templer, R. H., Smith, W. S., Hunt, A. N., and Jackowski, S. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 9032-9036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henneberry, A. L., Lagace, T. A., Ridgway, N. D., and McMaster, C. R. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12 511-520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henneberry, A. L., and McMaster, C. R. (1999) Biochem. J. 339 291-298 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henneberry, A. L., Wistow, G., and McMaster, C. R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 29808-29815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henneberry, A. L., Wright, M. M., and McMaster, C. R. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13 3148-3161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams, J. G., and McMaster, C. R. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 13482-13487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang, Y., MacDonald, J. I., and Kent, C. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 354-360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, Y., Sweitzer, T. D., Weinhold, P. A., and Kent, C. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 5899-5904 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lagace, T. A., Miller, J. R., and Ridgway, N. D. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 4851-4862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Northwood, I. C., Tong, A. H., Crawford, B., Drobnies, A. E., and Cornell, R. B. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 26240-26248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook, A., Bono, F., Jinek, M., and Conti, E. (2007) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76 647-671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King, M. C., Lusk, C. P., and Blobel, G. (2006) Nature 442 1003-1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strahl, T., Hama, H., DeWald, D. B., and Thorner, J. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 171 967-979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrews, B. J., Bader, G. D., and Boone, C. (2003) Nat. Biotechnol. 21 1297-1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puig, O., Caspary, F., Rigaut, G., Rutz, B., Bouveret, E., Bragado-Nilsson, E., Wilm, M., and Seraphin, B. (2001) Methods 24 218-229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bai, C., and Elledge, S. J. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 283 141-156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lange, A., Mills, R. E., Lange, C. J., Stewart, M., Devine, S. E., and Corbett, A. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 5101-5105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loewen, C. J., Young, B. P., Tavassoli, S., and Levine, T. P. (2007) The J. Cell Biol. 179 467-483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friesen, J. A., Park, Y. S., and Kent, C. (2001) Protein Expression Purif. 21 141-148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo, Y., Walther, T. C., Rao, M., Stuurman, N., Goshima, G., Terayama, K., Wong, J. S., Vale, R. D., Walter, P., and Farese, R. V. (2008) Nature 453 657-661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taneva, S., Dennis, M. K., Ding, Z., Smith, J. L., and Cornell, R. B. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 28137-28148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cornell, R. B., and Taneva, S. G. (2006) Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 7 539-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davies, S. M., Epand, R. M., Kraayenhof, R., and Cornell, R. B. (2001) Biochemistry 40 10522-10531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie, M., Smith, J. L., Ding, Z., Zhang, D., and Cornell, R. B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 28817-28825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevens, S. Y., Sanker, S., Kent, C., and Zuiderweg, E. R. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 947-952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sikorski, R. S., and Hieter, P. (1989) Genetics 122 19-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.