Abstract

A mechanism accounting for the robust catalase activity in catalase-peroxidases (KatG) presents a new challenge in heme protein enzymology. In Mycobacterium tuberculosis, KatG is the sole catalase and is also responsible for peroxidative activation of isoniazid, an anti-tuberculosis pro-drug. Here, optical stopped-flow spectrophotometry, rapid freeze-quench EPR spectroscopy both at the X-band and at the D-band, and mutagenesis are used to identify catalase reaction intermediates in M. tuberculosis KatG. In the presence of millimolar H2O2 at neutral pH, oxyferrous heme is formed within milliseconds from ferric (resting) KatG, whereas at pH 8.5, low spin ferric heme is formed. Using rapid freeze-quench EPR at X-band under both of these conditions, a narrow doublet radical signal with an 11 G principal hyperfine splitting was detected within the first milliseconds of turnover. The radical and the unique heme intermediates persist in wild-type KatG only during the time course of turnover of excess H2O2 (1000-fold or more). Mutation of Met255, Tyr229, or Trp107, which have covalently linked side chains in a unique distal side adduct (MYW) in wild-type KatG, abolishes this radical and the catalase activity. The D-band EPR spectrum of the radical exhibits a rhombic g tensor with dual gx values (2.00550 and 2.00606) and unique gy (2.00344) and gz values (2.00186) similar to but not typical of native tyrosyl radicals. Density functional theory calculations based on a model of an MYW adduct radical built from x-ray coordinates predict experimentally observed hyperfine interactions and a shift in g values away from the native tyrosyl radical. A catalytic role for an MYW adduct radical in the catalase mechanism of KatG is proposed.

Heme enzymes such as catalases and peroxidases are ubiquitous in aerobic organisms and are principally responsible for eliminating the potential damaging effects of hydrogen peroxide. The structure and function of the monofunctional enzymes have received abundant attention for many years, whereas the dual function enzyme, catalase-peroxidase (KatG),3 found in bacteria and fungi, is a relative newcomer and is less well characterized. In the pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which still infects and kills millions of people each year, KatG is the only catalase and is required for virulence (1, 2). The peroxidase activity of KatG is considered to be responsible for activation of the anti-tuberculosis therapeutic agent, isoniazid (3, 4), and mutations in this enzyme are the principal origin of widespread resistance to this pro-drug (5, 6).

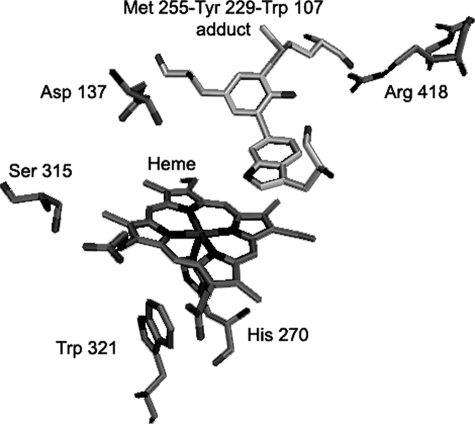

Investigation of the properties of KatG is of interest because the correlation between unusual features of its structure and particular mechanistic steps is not fully defined nor understood. The post-translational modification of residues Met255, Tyr229, and Trp107, the side chains of which form an adduct on the distal side of the heme (Fig. 1), is the most intriguing structural feature and is required for catalase but not peroxidase activity (7–10). KatG catalytic function has features in common with classical mono-functional enzymes; for example, an oxoferryl-porphyrin π-cation radical species is formed from resting enzyme in turnover with alkyl peroxides (11–13), and this intermediate is taken to be common to both peroxidase and catalase reaction paths. Its formation has not been observed in the presence of hydrogen peroxide however, except in mutants such as W107F and Y229F that lack catalase activity (7, 14). Interestingly, a poor rate of reaction with hydrogen peroxide of KatG Compound (Cmpd) I prepared using alkyl peroxide was recently presented as evidence that the catalase mechanism in KatG diverges from the typical monofunctional enzyme pathway exemplified by bovine liver catalase (15). A reaction between hydrogen peroxide and Cmpd I would be expected to constitute the second phase of the dismutation in which H2O2 acts as a two-electron reductant. A mechanism explaining the robust catalase activity exhibited by KatGs is therefore of special interest because novel mechanistic features are likely to be uncovered; Cmpd I is apparently not a catalytically competent intermediate, and high activity is absent from other homologous class I peroxidases. The near absence of catalase activity in KatG mutants in which replacements are made in the residues of the Met-Tyr-Trp (MYW) adduct strongly suggests a specific mechanistic role is filled by modification of the distal side residues.

FIGURE 1.

The distal side structure of M. tuberculosis KatG (from the coordinates of PDB code 2CCA) showing the covalent Met-Tyr-Trp adduct.

KatG dismutates hydrogen peroxide in a nonscrambling mechanism such that both oxygen atoms of dioxygen derive from the same molecule of hydrogen peroxide (16, 17). Unlike classical catalases, however, which do not accumulate intermediates during H2O2 turnover because of very rapid rates of both the peroxide reduction and the peroxide oxidation steps, KatG forms a species characteristic of oxyferrous heme (peroxidase Cmpd III) in the presence of high concentrations of peroxide (11, 15, 18). This intermediate is usually stable in peroxidases and is considered to be catalytically inert, but it must be highly unstable in KatG because catalase turnover occurs while the heme is in this form (In cytochrome c peroxidase oxyferrous heme is unstable because of internal redox chemistry involving Trp191, but cytochrome c peroxidase does not exhibit catalase activity (19).) and the catalase activity of the W321F mutant of M. tuberculosis KatG is only moderately reduced (20). In the companion paper (69), formation of oxyenzyme from the carbonyl enzyme shows that in WT KatG, oxyferrous heme is too stable to be a viable catalase intermediate unless some other unique feature produced in the oxyferrous enzyme formed in the presence of hydrogen peroxide alters its properties. A protein-based radical proposed here to be formed on the distal side amino acid adduct, which co-exists with oxyferrous heme when peroxide turnover occurs, is suggested to be a catalytically competent intermediate in catalase turnover in WT KatG.

Our focus here is on identifying intermediates formed in M. tuberculosis KatG during catalase turnover. Stopped-flow optical kinetics techniques are applied to follow the changes in heme oxidation state in parallel with rapid freeze-quench-EPR experiments used to monitor the production and decay of protein-based radicals. A heretofore unknown narrow doublet radical signal is characterized by X-band and D-band EPR spectroscopy. DFT calculations provide additional insights into the structure of the radical. A reaction scheme originally suggested in other work (15) is described, incorporating the new radical proposed to be localized on the MYW adduct into the catalase reaction pathway. A detailed analysis of the catalase reaction mechanism in M. tuberculosis KatG, the only catalase found in M. tuberculosis, contributes to our understanding of the biology of this pathogen, which resides in host macrophages upon infection and is subjected to extensive oxidative stress in that environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

M. tuberculosis KatG was prepared from an overexpression system in Escherichia coli strain UM262, as published previously (21), and was used usually within a few days of preparation. Mutagenesis was performed using the QuickChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Pairs of complementary primers (synthesized and purified by Operon Biotechnologies, Inc.) were designed to introduce the required mutations. The oligonucleotide pairs (mutated codons are in boldface) were as follows: Y390F, 5′-1153CGGGTGGATCCGATCTTTGAGCGGATCACGCGTC1186-3′ and 5′-1186GACGCGTGATCCGCTCAAAGATCGGATCCACCCG1153-3′ (4); M255A, 5′-748GAGACGTTTCGGCGCGCGGCCATGAACGACGTC780-3′ and 5′-780GACGTCGTTCATGGCCGCGCGCCGAAACGTCTC748-3′. Mutagenesis was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol, and the reaction products were transformed into the E. coli XL1-Blue strain for selection purposes. The presence of the mutated codons in the katG gene was confirmed by DNA sequencing (Gene Wiz, Inc.), and the mutated plasmid was electroporated into E. coli strain UM262 for protein overexpression. The mutants Y229F and W107F were prepared as reported previously (7, 22).

The catalase activity of purified KatG enzymes was evaluated optically based on the disappearance of H2O2, at pH 6 or 7, in 20 mm potassium phosphate buffer or in 20 mm sodium borate buffer, pH 8.5, according to published procedures (23). No direct comparison is presented for the rate of catalase turnover measured optically and the intensity changes in RFQ-EPR measurements (described below) under identical conditions because of the large difference in sensitivity of the two techniques; high enzyme concentration is needed for detection of the radical in EPR spectra, whereas such conditions produce bubbling in solutions that strongly interfere with absorbance measurements.

RFQ-EPR methodology has been published elsewhere (22, 24, 25); briefly, enzyme and peroxide solutions are mixed at room temperature in a 1:1 ratio, and the mixture is sprayed into a funnel attached to an EPR tube submerged in an isopentane bath held at approximately -130 °C. The frozen powder is packed into precision bore EPR tubes, and the packed sample, which retains isopentane, is frozen in liquid nitrogen. For quantitative EPR, signal intensity is based on a copper standard, and the total intensity for RFQ samples is multiplied by 2 to correct for isopentane dilution. The foaming of solutions because of the rapid evolution of dioxygen leads to further dilution by an additional variable amount around 2-fold, but no further correction of EPR signal intensity was made. In some cases, manually mixed samples were prepared in borate buffer, pH 8.5, by mixing protein solution (∼100 μm) with an 8000-fold molar excess of H2O2, loading the mixture into precision bore EPR tubes, and immediately immersing the tube in liquid nitrogen. EPR spectra were recorded on a Bruker E500 ElexSys X-band spectrometer with samples held either in a finger Dewar for spectra at 77 K or in an Oxford liquid helium cryostat for lower temperatures. Signal averaging was employed to improve the signal-to-noise ratio when needed. Simulation of X-band EPR spectra was performed using SimFonia software (Bruker). Optical stopped-flow spectroscopy was performed using a HiTech 16-DX instrument as described elsewhere (4, 7, 11) in the buffers listed above.

Cross-link Formation—To rule out the formation of dityrosine cross-links during catalase turnover, 10 μm WT KatG was incubated with 1000–8000-fold molar excess of H2O2 for 15 min at room temperature. SDS-PAGE of KatG from these samples was carried out using a PhastGel system (Amersham Biosciences).

DFT Calculations—DFT calculations for the analysis of MYW adduct models were carried out using the Gaussian 03 program package (26). Molecular structures were optimized at the B3LYP/6–31G* level of theory in combination with the pruned 99-point Euler-Maclaurin radial grid and 590-point angular grid for all atoms. In addition to a single molecule approximation (gas phase model), a mimic of the protein environment of the MYW adduct was explored by employing the polarizable continuum model (27) with various solvents spanning permittivity constants from 1 (vacuum) to about 80 (water). An initial geometry of the MYW adduct was built based on the coordinates for the covalently linked residues Met255, Tyr229, and Trp107 taken from the WT M. tuberculosis KatG structure (PDB entry 2CCA), from which we carried out a full optimization. All atoms of the side chains up to the C-α carbons (substituted by methyl groups) were optimized in the model. The relative position of the three C-α carbons and the two dihedral angles that freeze the rotations of the aromatic rings of the tyrosyl and tryptophanyl moieties with respect to their respective C-α atoms were kept constant retaining the values found in the x-ray structure. This set of constraints maintained the relative position of the MYW residues with respect to the backbone atoms (C-α carbons), whereas their relative position with respect to one another could be fully optimized.

The natural spin population analysis of the radical models was carried out as implemented in the NBO 5.0 program package (28). Hyperfine coupling values for hydrogen atoms in the radical models were computed and compared with experimental data. Reliability of the chosen level of theory (B3LYP/6–31G*) to predict the spin distribution and hyperfine parameters was examined by comparison of the calculated electron spin densities in free tyrosyl and neutral tryptophanyl radicals to experimental values (29, 30), which demonstrated a good agreement. An increased size of basis sets (6–311G**) did not affect computed spin distribution or hyperfine parameters significantly. The g value calculations for the radicals were performed using the ADF program package (31).

High Field-EPR D-band (130 GHz) spectra were obtained using a spectrometer assembled at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, that uses a quadrature detection bridge (100-milliwatt pulsed output) and probe supplied by HF EPR Instruments, Inc. (V. Krymov, New York). Cylindrical resonators operating in the TE011 mode provide typical π/2 pulse widths of 30–50 ns at maximum bridge power. The magnetic field is generated by a specially designed 7 tesla superconducting magnet with a ±0.5 tesla superconducting sweep/active shielding coil (Magnex Scientific). Frozen RFQ samples were held in quartz capillary tubes with inner and outer diameters of 0.5 and 0.6 mm, respectively, and an active volume of 0.2 μl. The frozen sample tubes were loaded into the probe under liquid nitrogen and inserted into the low temperature continuous flow cryostat (Oxford Instruments, Spectrostat model 86) and were maintained at 7 K to an accuracy of approximately ± 0.3 K using an ITC503 temperature controller. The magnetic field was calibrated to an accuracy of ∼2 G using a sample of Mn(II)-doped MgO (32). Field-swept two-pulse (Hahn) echo detected spectra were obtained with 180° phase cycling of the first pulse to provide suppression of base-line artifacts. Specific experimental parameters are given in the figure legends.

HF EPR spectra were simulated using software described previously (33, 34). The hyperfine interactions were treated to first order, and transition probabilities were taken as unity. To fit the 130 GHz echo-detected spectra, a weighted sum of two simulations having different gx values was required. Parameters for the simulations are given in the legend to Fig. 5. Uncertainty in the reported g values is ±0.00003 and for the hyperfine coupling value was ±0.5 G (33, 35).

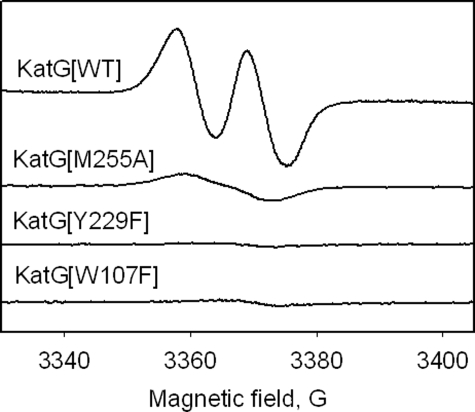

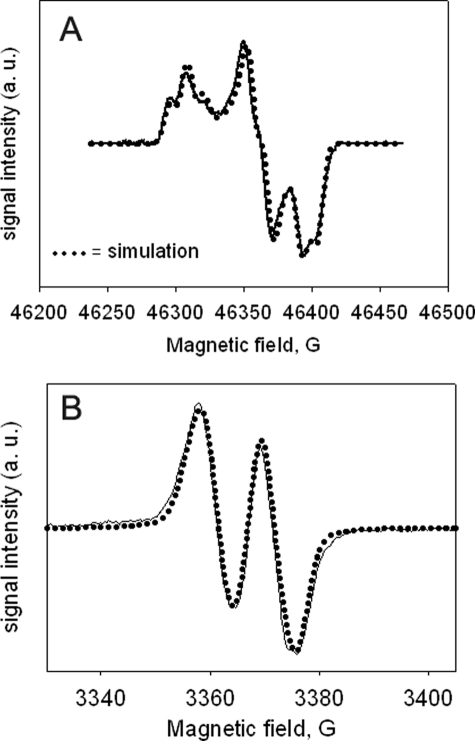

FIGURE 5.

Manual freeze quench samples of KatG distal side mutants treated with 8000-fold molar excess of H2O2 at pH 8.5. Spectra (average of nine scans) were recorded under the following conditions: T = 77 K, microwave frequency = 9.442 GHz; microwave power = 0.1 milliwatt; modulation amplitude = 1 G.

Preparation of RFQ Samples for High Field EPR—The RFQ apparatus and its calibration for preparation of the high frequency EPR samples will be described in detail elsewhere. Briefly, it consists of a System 1000 syringe driving ram (Update Instruments, Madison, WI) and associated reactor hoses to produce a sample frozen at 35 ms and the following components designed and manufactured in-house: a Wiskind-type mixing chamber, an ejection nozzle, a freezing unit comprising copper-beryllium alloy wheels, and a sample collection basin.4 Two syringes of equal volume were mounted on the ram unit; one was filled with the KatG solution (150 μm) and the other with 600 mm H2O2. A 25-hole spraying nozzle was attached to the outlet of the aging hose. The reaction mixture was ejected through the nozzle onto the rapidly rotating (1500 rpm) copper-beryllium alloy wheels cooled with liquid nitrogen. The frozen solution was continuously scraped off the wheels by stainless steel blades and was collected as a fine powder under liquid nitrogen. This powder was then divided and packed into either standard size precision bore quartz EPR tubes (4 mm outer diameter) for measurements at X-band or into capillaries for D-band measurements. The 4-mm tubes were attached to a glass funnel using heat-shrink tubing, and this assembly was immersed in isopentane kept at -140 °C; the sample powder was transferred into the funnel with cold metal spatulas and packed using a stainless steel packing rod with a Teflon tip. A packing factor of 0.8 was determined separately by comparing the volume of frozen and then melted contents of a tube. A home-built platform immersed in liquid nitrogen was used to pack D-band capillary tubes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RFQ-EPR and Optical Stopped-flow Experiments—The high catalase activity of M. tuberculosis KatG is conveniently measured in the presence of millimolar H2O2 without enzyme degradation or apparent inhibition. Among the accumulated mechanistic details for this unusual behavior in a class I peroxidase are the findings of a nonscrambling mechanism shown in isotope-ratio experiments (16), the finding that superoxide is not a product during turnover (16), and the demonstration that mutation of Met255, Tyr229, or Trp107, the side chains of which form the distal side adduct in KatG shown in Fig. 1, reduces the rate thousands-fold (7–10, 14, 36–38). A recent comprehensive kinetic study of heme intermediates formed during catalase turnover (15) and suggestions from that report provided the impetus for the application of RFQ-EPR spectroscopy to probe for protein-based radicals in the catalase reaction pathway in WT KatG and in several mutants. Optical stopped-flow experiments and low temperature EPR were also applied to be able to monitor the kinetics of changes in heme oxidation or spin state.

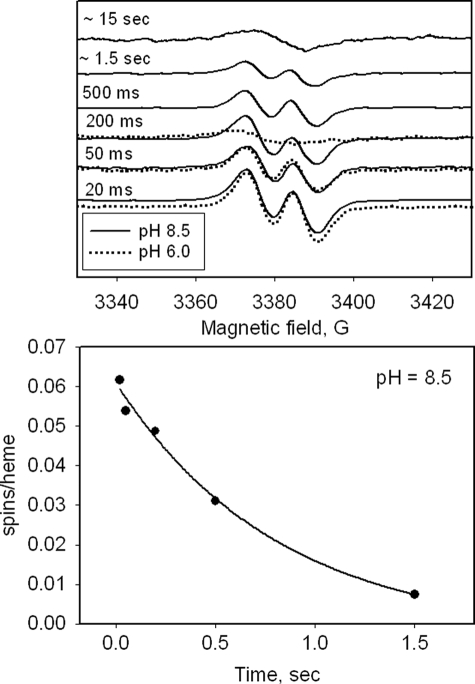

RFQ-EPR sampling allows mixing of ferric KatG with H2O2 followed by freeze-quenching of reactions in the millisecond time range. Fig. 2 (top) shows spectra recorded at 77 K in the g = 2 region as a function of incubation time after mixing KatG with a 1000-fold molar excess of H2O2 at pH ∼7 and ∼8.5. A narrow doublet signal at g = 2.0034 with a principal hyperfine splitting of ∼11 G appears at the earliest time point accessible here and was the only signal in the g = 2 region in spectra recorded at 77 K. The intensity of the signal was maximal in the sample frozen after 20 ms (∼0.1 spins/heme) and decayed thereafter until it was no longer detectable after ∼200 ms (Fig. 2, top) for the reaction run at pH ∼7. The actual spin concentration is likely greater than 0.1 spin/heme because the considerable foaming under these conditions dilutes the solutions; no correction is made for this dilution. At pH 8.5, the narrow doublet signal persisted ∼8 times longer (up to 1.7 s) (Fig. 2, bottom). When using an 8000-fold molar excess, the narrow doublet signal persists long enough that an EPR sample could be prepared by manually mixing ferric enzyme with peroxide and rapidly transferring and freezing the solution by immersion of the EPR tube in liquid nitrogen. This method for sample preparation was used below for examining radical formation in mutant enzymes.

FIGURE 2.

RFQ-EPR of M. tuberculosis KatG reacted with H2O2. Top, samples were frozen at the indicated time points after mixing ferric KatG with 1000-fold excess H2O2 at pH 7.2 or 8.5. Spectra (average of nine scans) were recorded using the following conditions: T = 77 K, microwave frequency = 9.442 GHz; microwave power = 0.1 milliwatt; modulation amplitude = 1 G. Bottom, intensity (spins/heme) of the narrow doublet EPR signal as a function of time in RFQ-EPR samples frozen after mixing KatG with 1000-fold excess of H2O2 at pH 8.5. The curve is a fit of the data to a single exponential function using Sigma Plot 9.0.

The catalase specific activity of M. tuberculosis KatG (∼4000 units/mg at pH 7 and ∼439 units/mg at pH 8.5) allows estimation that a 1000-fold excess of peroxide should be completely consumed within ∼0.2 s at pH 6 or 7 and after ∼1.6 s at pH 8.5. These time intervals correspond very well to the interval during which the radical is present, suggesting that it represents a kinetically competent intermediate of the catalase reaction pathway. The RFQ-EPR conditions are not amenable to optical experiments to directly follow the rate of disappearance of hydrogen peroxide because of active bubbling; therefore, no visual comparison in rates is presented for the results using these two techniques.

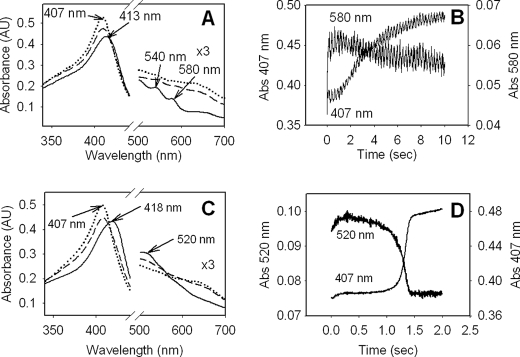

Stopped-flow optical experiments were performed to record changes in heme species at pH 6 and 8.5. Previous work had shown that small excesses of H2O2 do not lead to accumulation of new species (11). Upon mixing of enzyme with 1000-fold molar excess of H2O2 at pH 6, a species different from resting enzyme appears at the earliest time point (5 ms) (Fig. 3, A and B). This species lacks the CT bands of the resting (ferric) enzyme at 500 and 630–640 nm and has the features of oxyferrous enzyme, including a Soret maximum at 413 nm and with β and α bands at 545 and 579 nm. The spectrum of oxyferrous heme in M. tuberculosis KatG (11, 15) was confirmed in the companion paper (69). The reaction pathway to oxyenzyme can occur through reduction of Fe(IV) by peroxide, superoxide addition to ferric heme, or dioxygen binding to ferrous iron. The finding that this intermediate is observed only when very large excesses of hydrogen peroxide are present argues for the first pathway, which had been confirmed for M. tuberculosis KatG[Y229F] (7).

FIGURE 3.

Optical stopped-flow spectra of M. tuberculosis KatG reacted with H2O2. A, spectrum (solid line) recorded after 5 ms of incubation, an intermediate spectrum (dashed line) recorded 3.5 s after mixing, and a spectrum (dotted line) recorded 10 s after mixing KatG with 1000-fold excess of H2O2 at pH 6. B, time course of the reaction followed at 407 and 580 nm (pH 6). C, spectrum (solid line) recorded after 1.3 ms of incubation, an intermediate spectrum (dashed line) recorded 1.3 s after mixing, and a spectrum (dotted line) recorded 2 s after mixing KatG with 1000-fold excess of H2O2 at pH 8.5. D, time course of the reaction followed at 407 and 520 nm. These wavelengths correspond to the Soret maximum at the start of the time course and the new maximum in the visible region of the spectrum of the steady-state species formed at pH 8.5.

In similar experiments at pH 8.5, a different heme intermediate was found at the earliest time point. (The optical spectrum of the resting enzyme does not change as a function of pH from pH 6 to 8.5.) The new species has a Soret maximum at 418 nm, a broad shoulder at 521 nm, and no other prominent features in the visible region (Fig. 3C). The spectrum of this intermediate decayed sharply after ∼1.5 s (Fig. 3D), and upon reaction of the enzyme with 2000-, 4000-, and 8,000-fold molar excess of hydrogen peroxide persisted for longer periods proportional to the amount of peroxide added (data not shown). At pH 7, the optical spectrum formed in the first milliseconds was a mixture of the low and high pH species (data not shown). The time interval during which the oxyenzyme intermediate was observed at pH 6 (and also at pH 7) exceeded the time interval during which the narrow doublet EPR signal was detected (Fig. 2) and beyond the predicted time interval for complete consumption of peroxide assuming a linear reaction rate throughout. These observations indicate interesting features of the reaction pathway that are addressed under “Conclusions.”

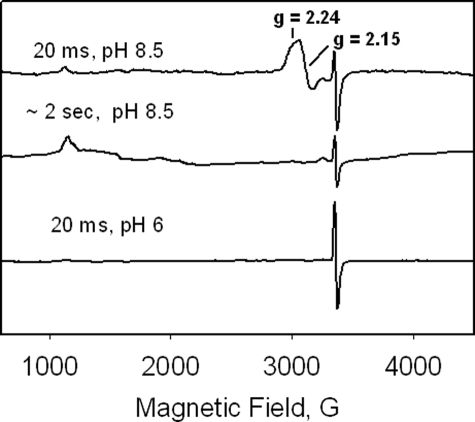

Low temperature EPR spectra of RFQ-EPR samples prepared at pH 7 did not contain a signal in either the g = 6 or the g = 2 regions that could be assigned to a paramagnetic intermediate (Fig. 4). This observation is consistent with the optical evidence for oxyferrous heme, which is nonparamagnetic. For the RFQ-EPR samples at pH 8.5, the resting enzyme signals around g = 6 were also absent, and a signal consistent with a low spin ferric heme species was detected in the g = 2 region during the catalase turnover interval. The new signal was broad, but two partially resolved features at g = 2.24 and 2.15 of what could be a rhombic signal were seen. The g values of the two features are similar to those reported for the deprotonated ferric-peroxo complex of myoglobin (39) or the peroxo-horseradish peroxidase complex (40). A third feature below g = 2 could not be resolved. These results indicate a change in the steady-state heme species from the oxyferrous intermediate to a proposed ferric-peroxo species at alkaline pH. Note that the actual pH of frozen RFQ-EPR samples in phosphate buffer will be below 7 because of a decrease in pH with temperature for this buffer. This artifact does not have any impact on the narrow doublet radical signal shown in Fig. 2, but it does remove the signal assigned to a ferric-peroxo species at alkaline pH in Tris-maleate buffer (Fig. 4), the pH of which is more resistant to changes with temperature.

FIGURE 4.

RFQ-EPR spectra of M. tuberculosis KatG reacted with 1000-fold molar excess of H2O2 frozen at the indicated time points. Spectra (average of 9 scans) were recorded under the following conditions: T = 4 K; microwave frequency = 9.3879 GHz; microwave power = 1 milliwatt; modulation amplitude = 4 G. At pH 8.5, a ferric heme iron intermediate is present (g = 2.24, 2.15, ?); At pH 7, the only signal present is the narrow doublet signal at g = 2.0034.

The optical spectrum of the pH 8.5 samples does not resemble that assigned to the ferric peroxo form of horseradish peroxidase or heme oxygenase (39, 40), whereas the EPR data are clearly consistent with a low spin ferric peroxy heme; the intermediate formed at pH 8.5 at room temperature had been confirmed elsewhere to be a ferric species because in the presence of cyanide, a typical six coordinate low spin ferric complex was directly formed from it (41). A complete understanding of the identity of all species under these conditions awaits further study.

Characterization and Identification of the Radical in WT KatG—Turnover of KatG with H2O2 is expected to generate Cmpd I (oxoferryl porphyrin π-cation radical), which in the experiments above is apparently rapidly reduced by endogenous electron transfer producing a radical on a protein site. The rate of this step is too rapid for finding Cmpd I in either the optical or the EPR data gathered here. In results published earlier, turnover of ferric M. tuberculosis KatG with alkyl peroxides such as PAA generated Cmpd I and also tyrosyl and tryptophanyl radicals. RFQ-EPR spectra of such samples contain wide doublet, singlet, and also a narrow doublet EPR signal (11, 22, 24) under certain conditions. Wide doublet and singlet signals were found when the enzyme was treated with PAA alone, and a narrow doublet signal was found in the presence of isoniazid. This drug is a peroxidase substrate but is also known to quench the wide doublet radical in M. tuberculosis KatG (22, 24, 42). The narrow doublet radical had been suggested to be localized on free Tyr229, i.e. on the tyrosine not incorporated into the MYW adduct in freshly isolated enzyme, and the wide doublet was also considered to represent a radical on this residue having a different ring orientation in the absence of bound isoniazid (22). Here we consider the following new interpretation of the earlier findings, the narrow and wide doublet signals may be localized on different sites and the narrow doublet only became evident when the radical giving the wide doublet was quenched by reaction with isoniazid. If this is the case, these two different radicals could be formed in tandem after Cmpd I is produced. A feature consistent with a contribution from the narrow doublet signal can be found superimposed on the wide doublet described in earlier reports (7, 22) (supplemental Fig. S1). The important observation for the current results is that a radical species giving a narrow doublet signal is suggested to be produced when ferric KatG is treated with alkyl peroxide or hydrogen peroxide, consistent with its formation from endogenous electron transfer initiated by Cmpd I. Further study is needed to confirm this idea.

Interestingly, turnover of WT KatG with excess H2O2 does not produce the wide doublet radical signal nor singlet signals seen when Cmpd I is generated by an alkyl peroxide (in the absence of H2O2). Also important is the observation that the narrow doublet radical does not propagate to other protein sites; for example, the initial wide doublet produced during reaction with PAA evolves to other species over a period of seconds (22, 24). Thus, the species giving the narrow doublet in the presence of H2O2 must decay in a reaction with a redox partner that does produce the same secondary protein radicals. These results strengthen the suggestion that the narrow doublet represents an obligatory radical intermediate of the catalase reaction.

EPR of Distal Side Mutants—Mutations in residues of the distal side MYW adduct in KatG are known to disrupt catalase activity but not peroxidase activity (7, 9, 14). EPR samples were prepared using KatG[Y229F], KatG[W107F], and KatG[M255A] reacted with 8000-fold excesses of H2O2. The narrow doublet EPR signal was not formed in any of these reactions (at pH 8.5) (Fig. 5). Instead, a very low yield of a singlet EPR signal was observed, as was found in similar experiments with KatG[W107F] and Y229F mutants using PAA (22). These observations are fully consistent with the suggestion that the radical species giving the narrow doublet signal in WT KatG plays a kinetically competent role for catalase turnover. The absence of catalase activity in these mutants could then be due to the loss of the radical or loss of a structural feature particular to the radical form of the WT enzyme. It is important to note that KatG[Y229F], W107F, and M255A mutants form oxyenzyme in the presence of excess hydrogen peroxide just as the WT enzyme does, which means that it is not loss of this heme intermediate that is responsible for the loss in catalase function. Furthermore, greatly enhanced stability of the oxyenzyme contributes to the lost catalase function in the KatG[Y229F] and W107F mutants (69).

High Field RFQ-EPR—More complete characterization of the structure of the radical giving rise to the narrow doublet EPR signal in WT KatG was pursued using high field RFQ-EPR spectroscopy. Here, a 4000-fold molar excess of peroxide was used to increase the yield of radical at an early time point and thereby improve the signal-to-noise in D-band experimental data. A rhombic signal with g values similar to those of tyrosyl radicals was found for samples frozen 35 ms after mixing resting KatG with H2O2 (Fig. 6A). The principal hyperfine splitting estimated to be 11 G through simulation of the spectrum (see below) demonstrated that this signal represents the same species as that found at X-band. Also, a portion of the identical sample used for the D-band measurements was loaded into a conventional EPR tube and examined at X-band; it exhibited a narrow doublet radical intensity equal to ∼20% of the heme concentration, approximately twice the yield estimated in the X-band data at 20 ms. The slow relaxation characteristics of the two-pulse echo-detected D-band EPR signal suggest that the radical site is isolated from other paramagnetic species. A similar conclusion was drawn based on the power saturation of the ND signal in X-band spectra (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

A, echo-detected pseudo-modulated D-band (130 GHz) RFQ-EPR spectrum of M. tuberculosis KatG frozen 35 ms after mixing resting enzyme with 4000-fold molar excess of H2O2 at pH 8.5. Pulse widths, 40 and 80 ns; interpulse delay, 120 ns; temperature, 7 K; repetition rate, 10 Hz; averages per point, 30; 16 scans, total scan time 73 min. The overlaid simulation (dotted line) was generated as described in the text using the following parameters. Species 1 (59% of total simulation): gx = 2.00606, gy = 2.00344, gz = 2.00186, Ax = 11.9 G; Ay = 10.3 G; Az = 10.3 G. Species 2 (41% of total simulation) with same parameters as Species 1 except gx = 2.00550. Note that the smaller (∼2 G) hyperfine coupling required to fit the X-band simulation is unresolved because of inhomogeneous broadening in the D-band spectra. B, RFQ X-band EPR spectrum (solid line) of WT KatG treated with 1000-fold excess H2O2 at pH 8.5 frozen 20 ms after mixing. Experimental conditions, T = 77 K, microwave frequency = 9.442 GHz; microwave power = 0.1 milliwatt; modulation amplitude = 1 G; average of nine scans. Dotted line, simulation using the following parameters: g1,2,3 = 2.00606, 2.00344, 2.00186; Aiso(1) = 10.5 G, Aiso(2) = 3.2 G; line broadening = 3.6 G (average.). a.u., arbitrary units.

Interestingly, simulation of the HF-RFQ-EPR data demonstrated that two different gx values, equal to 2.00550 and 2.00606, and a single isotropic hyperfine splitting of ∼11 G were required for simulating the 1:2:1 triplet feature at gx. The apparent splitting at gx is not because of the presence of two equivalent I = ½ hyperfine coupling interactions, which could also produce a triplet feature, because the X-band spectrum lacks the multiplicity expected if more than a single 11 G splitting were present. The principal g values (2.00606/2.00550, 2.00344, and 2.00186) obtained by simulation rule out peroxyl (43), glycyl (44, 45), tryptophanyl (30, 46, 47), and thiyl radicals (35, 48, 49).

The presence of multiple gx values has been documented in HF-EPR spectra of protein-based tyrosyl radicals in which a heterogeneous environment is present at the phenolic oxygen (50–52). The simulation shown in Fig. 6 was composed of nearly equal proportions of two rhombic signals differing only in the value of gx. The proximity of the two gx values and the similarity of the rest of the spectral features suggest that both signals likely arise from the same species in slightly different environments. The actual gy and gz values are quite invariant for known tyrosyl radicals and are in general equal to or larger than 2.0042 and 2.0020, which contrasts with the values here (35, 53–56). The anisotropy of the g matrix for the new radical signal (gx - gz = 0.00420 and 0.00364, gy - gz = 0.00158), however, is near the range typical of tyrosyl radicals (gx - gz ∼0.007 to 0.004, gy - gz = 0.002) (57). In addition, the rhombicity of the g matrix is similar to that expected for a tyrosyl radical, even though the isotropic g value is slightly below that observed previously in unmodified tyrosyl radicals. Thus, an electronically modified tyrosyl-like radical is reasonably predicted by these results.

Structural Information from the X-band Spectrum—Simulation of the narrow doublet spectrum could be confidently approached adopting the experimentally determined g values to obtain additional hyperfine coupling information. Simulations using a single isotropic hyperfine coupling value of ∼11 G to achieve the principal splitting produced a symmetrical line shape unlike that in the X-band spectrum. More satisfactory simulation was achieved by adding in a second weaker isotropic hyperfine coupling. Values of ∼10.5 and ∼3.2 G gave the most satisfactory fit to the data (Fig. 6B). Inclusion of additional hyperfine interactions with aiso values exceeding ∼2.5 G decreased the quality of fitting to the experimental spectrum. These observations limit the number and magnitude of interactions that can contribute to the narrow doublet line shape in addition to the main splitting. Note that the X-band experimental spectrum was recorded at very low power and modulation amplitude to ensure against microwave saturation and line shape distortions, and this spectrum is assumed to optimally indicate all the hyperfine features resolvable at this frequency. The impact on the spectra caused by the two gx values evaluated at D-band is negligible at X-band.

The two hyperfine interactions used in simulating the X-band spectrum are tentatively assigned to the β-methylene hydrogens of a tyrosyl-like radical. This assignment is consistent with the high field-EPR results demonstrating the isotropic nature of the ∼11 G hyperfine interaction, which is a feature of such couplings in tyrosyl radicals. Additional hyperfine splittings because of relatively strong anisotropic dipolar interactions for the 3′ and 5′ ring hydrogens would also be expected in the X-band spectrum if the species were an unmodified (native) tyrosyl radical, with aiso values around 6–7 G, and with the 2′ and 6′ hydrogens exhibiting weaker couplings of around 3 G (29, 53, 58). However, these interactions could not be included in the simulations without severely degrading the quality of the fits (data not shown). Couplings in the 6 G range are decidedly absent from the narrow doublet spectrum as they would introduce greater multiplicity in the line. In fact, the upper limit to additional hyperfine coupling interactions was ∼2.5 G as stated above. These observations suggest that couplings to ring hydrogens are less than 2.5 G or that the ring hydrogens are absent from the radical structure.

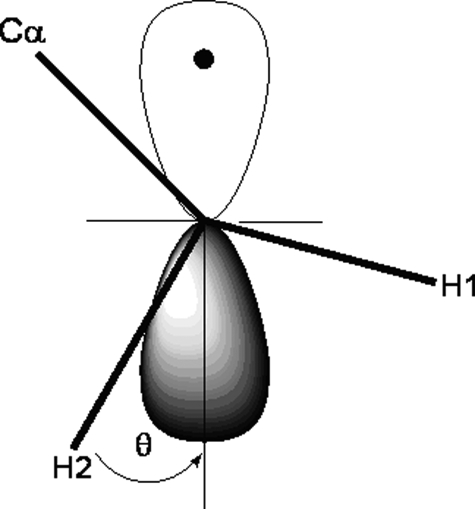

Further insights can be gained from the isotropic hyperfine coupling values assigned to a pair of β-methylene hydrogens if the spin density in the ring of the tyrosyl-like radical could be estimated. Then a prediction can be made about the couplings expected for the ring hydrogens. A user-friendly approach based on the McConnell equation designed for easy analysis of EPR spectra of tyrosyl radicals in proteins (59), which correlates hyperfine couplings with C-1 (C-γ) spin density and phenol ring plane orientation, shows that the experimental couplings of 10.5 and ∼3.2 G (±0.5) would arise for β-methylene hydrogens when a small ring orientation angle, θ, occurs (Fig. 7) in a radical in which the spin density on C-1 is ∼0.2. In this geometry, the weakly coupled hydrogen lies close to the plane of the ring, and the strongly coupled hydrogen lies close to the p-π singly occupied orbital direction on C-1 of the phenolic ring. Because there is some error in evaluating the hyperfine couplings by simulation of the X-band spectrum, a small range of θ angles is considered possible here. For ring orientations in a range with 10 > θ ≤ 30°, the spin density on carbon-1 of the phenolic ring would remain close to 0.2. An alternative geometry in which θ is close to ∼ 66° also predicts hyperfine couplings near 10.5 and ∼3.2 G, but in this case the C-1 spin density must be large (∼0.5). For the narrow doublet signal, this high spin density rules out assignment to a native tyrosyl radical because the EPR spectrum lacks typical hyperfine splittings that would be expected for 3′,5′ hydrogens and for 2′,6′ hydrogens (29). Furthermore, a spin density greater than ∼0.4 has not been observed in any tyrosyl radical reported to date nor do calculations predict densities significantly greater than that value (60). Therefore, the analysis points to the conclusion that the narrow doublet signal arises from a tyrosyl-like radical with low spin density at C-1 that may lack 3′,5′ hydrogens, or a tyrosyl radical with high spin density that cannot contain ring hydrogens. In either case, the radical giving the narrow doublet EPR signal must be localized on an electronically and/or structurally modified tyrosine residue according to both HF and X-band EPR analyses.

FIGURE 7.

β-Methylene hydrogen orientation with respect to the unpaired electron π-orbital perpendicular to the phenol ring plane in a tyrosyl radical. The angle θ is defined for the strongly coupled hydrogen in an arrangement similar to that for Tyr229 in M. tuberculosis KatG.

An MYW Adduct Radical?—The only structurally unusual tyrosine residue in KatG is Tyr229 linked within the distal side MYW adduct. Beyond this and upon inspection of the M. tuberculosis KatG crystal structure, one tyrosine residue that may also have unusual electronic properties is Tyr390. This residue exhibits a π-cation interaction with Arg249 (PDB code 2CCA) and also happens to have a small θ angle possibly consistent with the structural predictions above. The finding that KatG[Y390F] exhibits the same narrow doublet signal as WT KatG (supplemental Fig. S2) rules out assignment to this residue. There are no other tyrosines in the KatG structure with small θ angles. These observations and the loss of the narrow doublet EPR signal in mutants that lack the distal side adduct (KatG [Y229F], KatG [W107F], and KatG[M255A]) argues very strongly that this structure is either the site of the radical or is needed to produce the radical on another modified (electronically unusual) tyrosine in KatG.

A range of electronic environments for known tyrosyl radicals in proteins is usually attributed to hydrogen bonding effects at the phenolic oxygen. For example, in cases where there is relatively good hydrogen bonding, a gx value close to 2.006 is observed, whereas in the absence of hydrogen bonding, this value can be as large as 2.009 (53, 55, 59, 61). Calculations illustrate that the origin of the increased gx value in the absence of hydrogen bonding is associated with increased unpaired spin density on oxygen, which coincides with decreased unpaired spin density on C-1 of the ring (60, 62). The difference in spin density at C-1, however, is on the order of only 0.03 for the limiting cases in which an isolated tyrosyl radical (no hydrogen bond) is compared with one with a strong hydrogen bonding partner (imidazole) (60). For the narrow doublet here, whereas the gx value could be considered consistent with a good hydrogen bond at the phenolic oxygen of a tyrosyl-like radical (for example, the tyrosyl radical in PSII (63)), the predicted spin density at C-1 is much smaller than the typical values whether there is a polarizing interaction at the oxygen or not. Furthermore, the direction for change would be toward increased spin density in the ring with better hydrogen bonding, rather than an unusually low spin density suggested by the results above. Therefore, a native tyrosyl radical is again ruled out as the species giving the narrow doublet.

The atypical g values argue for some electronic effect other than hydrogen bonding that alters the spin density at C-1 in the tyrosyl-like radical. Knowledge that M. tuberculosis KatG treated with excess alkyl peroxide forms dimers because of di-tyrosine cross-links (64)5 opens the possibility that modified tyrosines could harbor a radical produced during catalase turnover. However, cross-linking of KatG does not occur during turnover of the enzyme with excess hydrogen peroxide, ruling out dityrosine as a locus for the narrow doublet radical.

To assist in assignment of the new KatG radical, DFT calculations were performed that focused on the electronic features of MYW adduct radicals. These calculations predicted a low spin density at the C-1 of the tyrosyl moiety (Tyr229) in an MYW radical, and predicted isotropic hyperfine couplings to the β-methylene hydrogens of Tyr229 in the range of the experimental values assigned above.

DFT Calculations, Energy Stabilization of MYW Radicals—In principle, the formation of a radical on the MYW adduct can be achieved by abstraction of hydrogen from the hydroxyl group of the phenolic ring of Tyr229 or from the indole nitrogen of Trp107 (or by other oxidations). Mechanistic details surrounding the pathway to the radical, including modeling of the participation of heme intermediates, is left to future studies. Other issues such as the effect of the polarizability of the environment surrounding the radical and geometry issues are of interest here.

The relative stabilization energy of three forms of the MYW radical and its native (closed shell) form were estimated using DFT calculations. The ionization potential of the fully protonated MYW species, which produces a cation radical on the tryptophanyl moiety, was found to be at minimum about 40 kcal/mol higher than the energy difference between the native (closed shell) MYW model structure and that calculated for the radical (open shell) formed by hydrogen atom abstraction from either the indole nitrogen or the phenolic hydroxyl. Of the latter two cases, abstraction of hydrogen from the phenolic oxygen (producing a species labeled here as MYW-O·) was energetically favored by about 13.5 kcal/mol in the gas phase model and by nearly 12 kcal/mol in the model in aqueous medium (see below) compared with abstraction from the indole nitrogen (MYW-N·) (Table 1). Furthermore, as illustrated below, most unpaired spin density is localized on the tyrosyl moiety in the MYW-O· species, although some delocalization occurs. These observations are consistent with the experimental finding of a tyrosyl-like radical. The favored deprotonation of the phenol ring in the MYW adduct radical bearing protonated indole is in agreement with a previous report addressing the electronic structure of the Cmpd I intermediate in KatG and the energetics of nearby protein-based radicals (34).

TABLE 1.

Selected geometric parameters and relative energy of the reduced (closed shell) and oxidized (open shell) forms of the MYW adduct Gas phase data shown in normal font and polarizable continuum model (water) data in italic type.

| Geometry parameter | X-ray data | MYW-O· | MYW-N· | MYW | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met255–Tyr229 (S–C-ε2) (Å) | 2.01 | 1.793 | 1.793 | 1.787 | 1.793 | 1.786 | 1.791 |

| Tyr229–Trp107 (C-ε1–C-η1) (Å) | 2.022 | 1.453 | 1.456 | 1.486 | 1.487 | 1.486 | 1.489 |

| Met255–Tyr229 torsiona (degrees) | 20.14 | 10.88 | 22.73 | 53.34 | 57.61 | 54.24 | 57.61 |

| Tyr229–Trp107 torsionb (degrees) | 0.24 | 24.38 | 28.7 | 49.12 | 51.17 | 49.8 | 53.4 |

| Tyr229–Trp107 tiltc (degrees) | 159.92 | 178.81 | 178.84 | 179.63 | 177.81 | 177.81 | 177.44 |

| Energy (kcal/mol) | 0 | 0 | 13.48 | 11.81 | –81.47d | –82.61d | |

Torsion is defined as the (Cγ-SMet-255) – (C-ε2–C-δ1)Tyr-229 dihedral angle

Torsion is defined as the value of the dihedral angle {180° – 〈((C-δ1–C-ε1)(Tyr-229) – (C-η2–C-ζ1)(Trp-107))}

Out of plane deformation was defined as the angle formed between the (C-ε1)Tyr-229 – (C-η2–C-δ2)Trp-107 bonds

Adjusted to the MYW-O· energies by subtracting 0.5 absorbance units (Hartrees) for the lost hydrogen atom

Geometry of MYW Species—All essential geometric parameters, including bond distances, dihedral and tilt angles within the MYW adduct model that correspond to the Met255, Tyr229, and Trp107 side chains as they are found in the x-ray crystal structure of M. tuberculosis KatG from this laboratory (PDB code 2CCA), and the values for these parameters from DFT calculations are shown in Table 1. The x-ray data contain fairly long bond lengths of about 2.0 Å between the C-ε1 of Tyr229 and the C-η of the Trp107 side chain (C–C bond) and between the sulfonium of Met255 and the C-ε2 of the Tyr229 side chain (S–C bond) in the MYW adduct. X-ray structures of other KatG enzymes have somewhat shorter (1.686 Å in PDB code 1MWV at 1.7 Å resolution) or even longer (2.224 Å in PDB code 2B2R at 1.9 Å resolution) bond lengths for the Tyr229-C-ε1–Trp107-C-η bonds. These values are not reproduced by computational modeling of the MYW adduct, either for the closed shell or the open shell (radical) models, in which the C-ε1–C-η distance is consistently around 1.45 Å and the S-C-ε2 distance is around 1.8 Å. The optimum Tyr229–Trp107 torsion angle {180° - 〈[(Cδ1-Cε1)(Tyr-229)-(Cη2-Cζ1)(Trp-107)]} in the radical or native (closed shell) form of the model was around 24.4° (gas phase) or 28.7° for the model in an aqueous environment. A slightly larger change due the polarizability of the medium was predicted for the SMet-255–C-ε2Tyr-229 torsion angle that increased from about 10.9° in vacuum to 22.7° in aqueous environment. The increased swing around the S–C bond is likely because of changes in the magnitude of electrostatic interaction of the exposed sulfur lone pair orbital with the polarizable environment. The geometry of the optimized MYW model closely matches that of the crystal structure of M. tuberculosis KatG (supplemental Fig. S3).

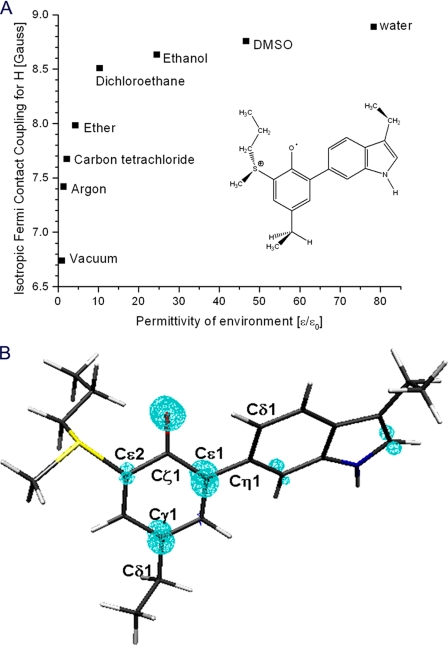

Spin Distribution—For closer investigation of the character and potential function of the MYW-O· adduct radical, computations also focused on analysis of unpaired electron distribution and exploration of possible factors that might modulate the spin distribution within the adduct. Hyperfine coupling parameters for the various hydrogens in the adduct radical models are governed by the unpaired spin distribution. Knowledge of these couplings is required to predict the EPR spectra for any model based on the DFT results. As described above, the torsion angle for the ethyl groups with respect to the phenol or indole ring in the adduct models was kept constant to preserve the relative orientation of the side chains with respect to the backbone (C-α atoms). With this constraint, the computed isotropic Fermi contact coupling constants for the β-methylene hydrogen atoms bound to C-β (C-3) of Tyr229 may be directly compared with the values of 10.5 and 3.2 G estimated based on the X-band EPR spectra. The corresponding hyperfine couplings from the DFT calculations for the optimized structure of the MYW-O· radical in vacuum were 6.6 and 0.1 G. These low values suggest that the spin density on the tyrosyl ring is being underestimated, whereas the finding of a large and a quite small hyperfine coupling value parallels the experimental results. A range of values was calculated by the following: 1) altering the polarizability of the medium surrounding the adduct model to introduce electrostatic interactions; and 2) altering the Tyr-Trp dihedral angle (Tyr229–Trp107 torsion). Thus, manipulating an external feature of the system (the electrostatic environment provided by the protein) and an internal feature of the model (the steric interactions imposed by the protein) could be explored. Fig. 8A shows that the Fermi contact coupling constant increases from about 6.6 G in a vacuum to about 8.2 G in the highly polarizable aqueous environment for the strongly coupled β-methylene hydrogen of the tyrosyl moiety of MYW-O·. A steep increase is predicted even for relatively nonpolarizable solvents such as carbon tetrachloride or dichloroethane compared with vacuum. This result demonstrates that even weak polarization could increase the values of the hyperfine coupling for β-methylene hydrogens because of an increase in the spin density within the tyrosyl moiety of the MYW-O· species and a decrease within the tryptophan moiety, without any significant alteration in geometry.

FIGURE 8.

A, environmental effect on computed isotropic Fermi coupling constant for the strongly couple hydrogen atom bound to the C-β carbon of Tyr229 in the MYW-O· adduct radical. B, DFT calculated unpaired spin density distribution (shown in blue) for the adduct using the polarizable continuum model (water) (isovalue = 0.012 e).

Additional increase of the spin density in the tyrosyl ring and an increase in hyperfine coupling parameters was found upon changing the Tyr-Trp torsion angle defined as the value of the dihedral angle {180° - 〈((C-δ1—C-ε1)(Tyr-229) – (C-η2—C-ζ1)(Trp-107))} as shown in supplemental Fig. S4. The calculated potential energy surface for this kind of reorientation exhibits a quite shallow minimum of about 1.5 kcal/mol in aqueous environment, which is even smaller in vacuum for distortions as large as 20–30° away from the energetic minimum (supplemental Fig. S5). Therefore, the small energy cost for torsion angle changes can easily be accommodated within the protein, and redistribution of the unpaired spin in the radical can occur because of small changes in structure. A 25° distortion from the undistorted (minimum) position in which the Tyr-Trp rotational angle is around 50° has an energy cost less than 1.5 kcal/mol and produces a hyperfine coupling value of 10.8 G in excellent agreement with the empirically determined value. The calculated coupling constant for the second hydrogen is 2 G in this species, also in good agreement with the 3.2 G value determined by simulation of the X-band spectrum. The unpaired spin density at C-1 (C-γ) in this model is 0.2 (see below).

The spin distribution in the MYW-O· radical model in aqueous environment with the dihedral Tyr-Trp angle that gives the best agreement with experimental data is shown in Fig. 8B. As expected, the spin density is localized mainly on the oxygen and within the phenolic ring of Tyr229, consistent with a radical expected to exhibit the EPR characteristics of a tyrosyl radical. Also, DFT calculation of the g values for the MYW-O· radical in aqueous environment predicts an anisotropy similar to that of tyrosyl radicals without hydrogen bonding at the phenolic oxygen (gz = 2.002420, gy = 2.004452, and gx = 2.009858). (No H-bonding interaction was included in the calculations at this time.) These values did not change significantly upon distortion of the Tyr-Trp torsion angle. For comparison, the g values calculated for a free tyrosyl radical were gx = 2.012683, gy = 2.005204, gz = 2.002137. The calculated values do not correspond perfectly in either case to experimental values and are generally larger as reported elsewhere for DFT calculations of these parameters (60), but the decrease in gx and gy values predicted for the MYW-O· radical compared with a native tyrosyl radical agrees with experiment results and helps confirm the assignment of the radical.

The calculated hyperfine coupling values for all hydrogens (data not shown) in the MYW-O· structure predict that only the larger β-methylene hydrogen hyperfine coupling is great enough to be directly observed as a splitting in the X- or D-band spectrum. Moreover, some difference in g values would be expected for the MYW-O radical compared with a native tyrosyl radical because of delocalization of spin throughout the adduct. (Note that the total spin on all carbons plus the nitrogen of the tryptophanyl moiety is 0.36, with 0.61 on the tyrosyl part.) However, no major changes in g matrix are predicted because there is negligible spin delocalization into the sulfur of Met255 in the MYW-O· model. These results may be compared with those for the modified tyrosyl radical in apogalactose oxidase, which has a covalent S–C bond to a cysteinyl sulfur and non-negligible spin density on the sulfur atom. The g tensor values of 2.00741, 2.00641, and 2.00211 (35) exhibit an anisotropy in the range typical of tyrosyl radical but an altered gy value far from that observed here.

The spin density on C-1 calculated here for the MYW-O· species in a polar environment (∼0.2) is in excellent agreement with the value given by the McConnell relation based on the empirical hyperfine couplings for the β-methylene protons. Also, the spin density on the oxygen of the adduct radical is calculated to be ∼0.285, whereas in native tyrosyl radicals it is ∼0.3. Thus, the electronic structure of the Tyr229 moiety of the adduct radical deviates from a native tyrosyl radical most noticeably in exhibiting low spin density at C-1.

Recently reported DFT calculations for the electronic structure of Cmpd I in KatG suggested localization of a radical mainly on the MYW adduct or on the proximal Trp (Trp321 in M. tuberculosis KatG) but not on the porphyrin. The spin density distribution was proposed to be dependent on the protonation state of the tyrosine of the MYW adduct and/or the conformation of the nearby side chain of Arg418 and included a radical on the proximal Trp residue in all cases (65). Although it would be interesting to compare our results to these calculated predictions, especially to help understand the pH dependence of the catalase reaction, the steady-state intermediates under our experimental conditions are different from Cmpd I, and an entirely new mechanism is proposed. One conclusion drawn in the calculations by Vidossich et al. (65) is that a radical should remain in proximity to the heme during the catalase reaction but may move to a new amino acid site when the catalase reaction is suppressed. This idea is in agreement with our experimental observation of only the narrow doublet radical assigned to the MYW adduct during catalase turnover and to “leakage” of this radical to remote sites found during turnover of alkyl peroxides in the absence of hydrogen peroxide. However, a shift in the redox state of the heme to Cmpd III in our model rather than a shift in the electronic properties of Cmpd I is the reason that the MYW radical does not relocate to remote sites. Evidence for a porphyrin π-cation radical and for radical formation on Trp321 but not on the MYW radical, under noncatalytic conditions, was recently published (42). To date, no experimental evidence for a radical on the MYW adduct has been presented under any conditions. The role of Arg418 in modulating catalytic functions of KatG as a function of pH has also been addressed elsewhere without including the possibility of an MYW adduct radical (37). The results presented here and in the companion paper (69) suggest that a reexamination of the structure of intermediates in catalytic functions of KatG is warranted.

Conclusions—The presence of a tyrosyl-like radical in M. tuberculosis KatG during catalase turnover has been demonstrated by RFQ-EPR spectroscopy. The persistence of this radical correlates with the amount of H2O2 present during catalase turnover, and therefore it can be considered a catalytically competent species in the catalase cycle. The arguments in favor of assignment of the observed narrow doublet radical to the MYW adduct are as follows: 1) the g tensor anisotropy is within the range of that expected for a tyrosyl radical, but the principal g values deviate from known unmodified tyrosyl radicals; 2) the narrow line width of the signal seen at X-band is consistent with a tyrosyl-like radical having a modified electronic structure; 3) the observation that Y229F, W107F, and M255A mutants do not exhibit the WT narrow doublet radical and have negligible catalase activity; and 4) the prediction by DFT calculations of structural and electronic properties for an MYW-O· species matching experimentally derived parameters.

Tyrosyl radicals have been found in the mono-functional catalases from human (66), bovine (67), and Proteus mirabilis (13) when treated with alkyl peroxide under conditions in which Cmpd I decays through endogenous electron transfers. No role for these radicals directly related to the dismutation of hydrogen peroxide in the catalase reaction pathway has been assigned. For KatG, because the steady-state form of the heme site during catalase turnover is oxyferrous (at neutral pH), the radical must fulfill a special redox or structural role that ensures release of dioxygen from the enzyme (see Scheme 1).

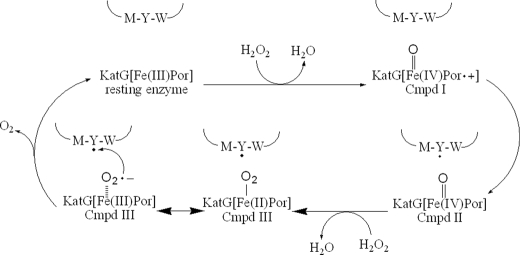

SCHEME 1.

Proposed catalase reaction pathway.

Treatment of M. tuberculosis KatG with a high concentration of H2O2 does not produce any detectable yield of the dimers and trimers formed upon treatment with alkyl peroxide. Therefore, the pathway to a surface tyrosyl radical able to produce cross-links is absent during catalase turnover. This behavior is expected from the finding of only the narrow doublet EPR species in the presence of high H2O2 and is considered evidence for the following: 1) the radical giving the narrow doublet is not available for cross-linking as a surface radical would be, and 2) the radical does not propagate to other sites as seen upon turnover with alkyl peroxide, which ultimately leads to radical formation on residue Tyr353 (22, 25) and others sites. The lack of formation of radicals other than the narrow doublet during catalase turnover is good evidence that it represents an obligatory intermediate of the catalase reaction and that it turns over rapidly enough such that secondary radicals do not form. In the presence of alkyl peroxide, the enzyme cycles through Cmpd I and ultimately returns to ferric enzyme. The MYW radical that must also be formed under those conditions may be rapidly quenched by electron transfers from other amino acid sites rather than by reaction with a species involved in catalase turnover. This other species is assumed to be superoxide released from oxyferrous heme, an intermediate that is not formed in the presence of alkyl peroxide.

Based on these observations, a scheme for the catalase reaction in KatG that incorporates a radical on the MYW adduct can be drawn similar to suggestions by Jakopitsch et al. (15). The reaction is proposed to proceed via a rapid rate of formation of Cmpd I, its rapid conversion to oxoferryl heme (peroxidase Cmpd II or an isoelectronic species) simultaneous with formation of the MYW radical, followed by a rapid second reaction with hydrogen peroxide to produce oxyferrous heme, which decomposes to ferric enzyme and superoxide, and ultimately dioxygen and the closed shell MYW adduct. At alkaline pH, the reaction is rate-limited upon formation of a ferric peroxo heme species (Compound 0) which is the earliest intermediate to appear. The rapid formation of Cmpd III in KatG[W107F] demonstrates that the MYW adduct is not required for the steps leading to the oxyenzyme intermediate (also true for Y229F and M255A (69)), but the distal side structure in the absence of the adduct is partly or entirely responsible for the stabilization of this form in the mutants. Also, as shown in the companion paper (69), the relatively long lifetime of oxyferrous WT KatG produced from the carbonmonoxy form in enzyme that lacks the radical demonstrates a unique function governed by the MYW radical.

The observation of the persistence of the spectrum of oxyenzyme beyond the time interval expected to be required to consume excess hydrogen peroxide shown in Fig. 3B can result from the likely phenomenon that as H2O2 is depleted, the rate of the reaction of oxyferryl heme with peroxide assumed to generate the oxyenzyme decreases, and the intermediate that contains the unique radical species can proceed down pathways that deviate from the catalase reaction path because of extraneous electron transfers depleting this radical in a noncatalytic step. In other words, the rate of internal electron transfers depleting the initial radical begins to outpace the rate of the second reaction with H2O2. Without the key radical, oxyenzyme decays too slowly to participate in catalase turnover (on the order of minutes), and this species can accumulate as the level of peroxide falls. Thus, peroxide will be used up with no apparent inhibition for nearly the entire course of catalase turnover, but the enzyme may exhibit the spectrum of the oxy form beyond the catalase turnover interval. At alkaline pH, there is no evidence for the oxyenzyme species because of changes in the rates of one or more steps and the stability of intermediates that cannot be speculated about at this time.

The MYW-O· radical provides a reasonable site for an electron transfer step to enable release of dioxygen from oxyferrous heme, which may be more accurately described as a ferric-superoxo heme complex. As the protein-based MYW radical is reduced by dissociated superoxide, the heme returns to a ligand free ferric state, and a cycle is completed with the stoichiometry of peroxide dismutation the same as in the classical monofunctional enzymes. Furthermore, the nonscrambling formation of dioxygen (16) is also explained as both atoms of released dioxygen come from a species in which two oxygen atoms are bound. The outlined mechanism does not invoke any heme intermediates not already recognized in peroxidase catalytic pathways but does not yet account for the proton inventory of the reactions.

One mechanistically critical feature in Scheme 1 is that electron transfer from superoxide to tyrosyl radical is a reasonable process according to a recent report in which this and other possibilities, such as addition of superoxide to the phenolic ring of tyrosyl radicals, is described (68). Thus, Tyr229 in the MYW adduct of KatG can serve the function of catalyzing oxygen formation from superoxide dissociating from oxyenzyme during the catalase reaction, but importantly, the ring is protected from covalent modification by superoxide because of its incorporation into the MYW adduct.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AI060014 (NIAID) (to R. S. M.) and GM075920 (to G. J. G.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: KatG, catalase-peroxidase; KatG[W107F], W107F mutant of KatG; KatG[Y229F], Y229F mutant of KatG; KatG[M255A], M255A mutant of KatG; Cmpd, Compound; PAA, peroxyacetic acid; MYW, Met-Tyr-Trp adduct; WT, wild type; PDB, Protein Data Bank; DFT, density functional theory.

J. Manzerova, V. Krymov, and G. Gerfen, unpublished results.

J. Suarez and R. S. Magliozzo, unpublished observations.

References

- 1.Collins, D. M. (1996) Trends Microbiol. 4 426-430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pym, A. S., Domenech, P., Honore, N., Song, J., Deretic, V., and Cole, S. T. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 40 879-889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnsson, K., King, D. S., and Schultz, P. G. (1995) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117 5009-5010 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu, S., Girotto, S., Lee, C., and Magliozzo, R. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 14769-14775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pym, A. S., and Cole, S. T. (2002) in Bacterial Resistance to Antimicrobials: Mechanisms, Genetics, Medical Practice and Public Health (Wax, R., Lewis, K., Salyers, A., and Taber, H., eds) pp. 355-403, Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York

- 6.Hazbon, M. H., Brimacombe, M., Bobadilla del Valle, M., Cavatore, M., Guerrero, M. I., Varma-Basil, M., Billman-Jacobe, H., Lavender, C., Fyfe, J., Garcia-Garcia, L., Leon, C. I., Bose, M., Chaves, F., Murray, M., Eisenach, K. D., Sifuentes-Osornio, J., Cave, M. D., Ponce de Leon, A., and Alland, D. (2006) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50 2640-2649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu, S., Girotto, S., Zhao, X., and Magliozzo, R. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 44121-44127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Regelsberger, G., Jakopitsch, C., Furtmuller, P. G., Rueker, F., Switala, J., Loewen, P. C., and Obinger, C. (2001) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 29 99-105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakopitsch, C., Auer, M., Ivancich, A., Ruker, F., Furtmuller, P. G., and Obinger, C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 20185-20191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillar, A., Peters, B., Pauls, R., Loboda, A., Zhang, H., Mauk, A. G., and Loewen, P. C. (2000) Biochemistry 39 5868-5875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chouchane, S., Lippai, I., and Magliozzo, R. S. (2000) Biochemistry 39 9975-9983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regelsberger, G., Jakopitsch, C., Engleder, M., Ruker, F., Peschek, G. A., and Obinger, C. (1999) Biochemistry 38 10480-10488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivancich, A., Jouve, H. M., Sartor, B., and Gaillard, J. (1997) Biochemistry 36 9356-9364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghiladi, R. A., Medzihradszky, K. F., and Ortiz de Montellano, P. R. (2005) Biochemistry 44 15093-15105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jakopitsch, C., Vlasits, J., Wiseman, B., Loewen, P. C., and Obinger, C. (2007) Biochemistry 46 1183-1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vlasits, J., Jakopitsch, C., Schwanninger, M., Holubar, P., and Obinger, C. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581 320-324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato, S., Ueno, T., Fukuzumi, S., and Watanabe, Y. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 52376-52381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakopitsch, C., Wanasinghe, A., Jantschko, W., Furtmuller, P. G., and Obinger, C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 9037-9042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller, M. A., Bandyopadhyay, D., Mauro, J. M., Traylor, T. G., and Kraut, J. (1992) Biochemistry 31 2789-2797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu, S., Chouchane, S., and Magliozzo, R. S. (2002) Protein Sci. 11 58-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcinkeviciene, J. A., Magliozzo, R. S., and Blanchard, J. S. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 22290-22295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranguelova, K., Girotto, S., Gerfen, G. J., Yu, S., Suarez, J., Metlitsky, L., and Magliozzo, R. S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 6255-6264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beers, R. F., Jr., and Sizer, I. W. (1952) J. Biol. Chem. 195 133-140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chouchane, S., Girotto, S., Yu, S., and Magliozzo, R. S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 42633-42638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao, X., Girotto, S., Yu, S., and Magliozzo, R. S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 7606-7612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., Montgomery, J. A., Jr., Vreven, T., Kudin, K. N., Burant, J. C., Millam, J. M., Iyengar, S. S., Tomasi, J., Barone, V., Mennucci, B., Cossi, M., Scalmani, G., Rega, N., Petersson, G. A., Nakatsuji, H., Hada, M., Ehara, M., Toyota, K., Fukuda, R., Hasegawa, J., Ishida, M., Nakajima, T., Honda, Y., Kitao, O., Nakai, H., Klene, M., Li, X., Knox, J. E., Hratchian, H. P., Cross, J. B., Bakken, V., Adamo, C., Jaramillo, J., Gomperts, R., Stratmann, R. E., Yazyev, O., Austin, A. J., Cammi, R., Pomelli, C., Ochterski, J. W., Ayala, P. Y., Morokuma, K., Voth, G. A., Salvador, P., Dannenberg, J. J., Zakrzewski, V. G., Dapprich, S., Daniels, A. D., Strain, M. C., Farkas, O., Malick, D. K., Rabuck, A. D., Raghavachari, K., Foresman, J. B., Ortiz, J. V., Cui, Q., Baboul, A. G., Clifford, S., Cioslowski, J., Stefanov, B. B., Liu, G., Liashenko, A., Piskorz, P., Komaromi, I., Martin, R. L., Fox, D. J., Keith, T., Al-Laham, M. A., Peng, C. Y., Nanayakkara, A., Challacombe, M., Gill, P. M. W., Johnson, B., Chen, W., Wong, M. W., Gonzalez, C., and Pople, J. A. (2004) Gaussian 03, Revision C.02. Gaussian, Inc, Wallingford, CT

- 27.Cossi, M. S., G., Rega, N., and Barone, V. (2002) J. Chem. Phys. 117 43-54 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glendening, E. D. B., J. K., Reed, A. E., Carpenter, J. E., Bohmann, J. A., and Morales, C. M. (2001) NBO 5.0, Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI

- 29.Bender, C. J., Sahlin, M., Babcock, G. T., Barry, B. A., Chandrashekar, T. K., Salowe, S. P., Stubbe, J., Lindstroem, B., Petersson, L., Ehrenberg, A., and Sjoberg, B.-M. (1989) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111 8076-8083 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lendzian, F., Sahlin, M., MacMillan, F., Bittl, R., Fiege, R., Pötsch, S., Sjöberg, B.-M., Gräslund, A., Lubitz, W., and Lassmann, G. (1996) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118 8111-8120 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baerends, E. J., Berger, J. A., Bérces, A., Bickelhaupt, F. M., Bo, C., de Boeij, P. L., Boerrigter, P. M., Cavallo, L., Chong, D. P., Deng, L., Dickson, R. M., Ellis, D. E., van Faassen, M., Fan, L., Fischer, T. H., Fonseca Guerra, C., van Gisbergen, S. J. A., Götz, A. W., Groeneveld, J. A., Gritsenko, O. V., Grüning, M., Harris, F. E., van den Hoek, P., Jacob, C. R., Jacobsen, H., Jensen, L., Kadantsev, E. S., van Kessel, G., Klooster, R., Kootstra, F., Krykunov, M. V., van Lenthe, E., Louwen, J. N., McCormack, D. A., Michalak, A., Neugebauer, J., Nicu, V. P., Osinga, V. P., Patchkovskii, S., Philipsen, P. H. T., Post, D., Pye, C. C., Ravenek, W., Rodriguez, J. I., Romaniello, P., Ros, P., Schipper, P. R. T., Schreckenbach, G., Snijders, J. G., Solà, M., Swart, M., Swerhone, D., te Velde, G., Vernooijs, P., Versluis, L., Visscher, L., Visser, O., Wang, F., Wesolowski, T. A., van Wezenbeek, E. M., Wiesenekker, G., Wolff, S. K., Woo, T. K., Yakovlev, A. L., and Ziegler, T. (2007) ADF 2007.01, SCM, Theoretical Chemistry, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- 32.Burghaus, O., Rohrer, M., Gotzinger, T., Plato, M., and Mobius, K. (1992) Meas. Sci. Technol. 3 765-774 [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Donk, W. A., Stubbe, J., Gerfen, G. J., Bellew, B. F., and Griffin, R. G. (1995) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117 8908-8916 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerfen, G. J., Licht, S., Willems, J.-P., Hoffman, B. M., and Stubbe, J. (1996) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118 8192-8197 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerfen, G. J., Bellew, B. F., Griffin, R. G., Singel, D. J., Ekberg, C. A., and Whittaker, J. W. (1996) J. Phys. Chem. 100 16739-16748 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghiladi, R. A., Knudsen, G. M., Medzihradszky, K. F., and de Montellano, P. R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 22651-22663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carpena, X., Wiseman, B., Deemagarn, T., Herguedas, B., Ivancich, A., Singh, R., Loewen, P. C., and Fita, I. (2006) Biochemistry 45 5171-5179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jakopitsch, C., Obinger, C., Un, S., and Ivancich, A. (2006) J. Inorg. Biochem. 100 1091-1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia-Serres, R., Davydov, R. M., Matsui, T., Ikeda-Saito, M., Hoffman, B. M., and Huynh, B. H. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 1402-1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denisov, I. G., Makris, T. M., and Sligar, S. G. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 42706-42710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jakopitsch, C., Droghetti, E., Schmuckenschlager, F., Furtmuller, P. G., Smulevich, G., and Obinger, C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 42411-42422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh, R., Switala, J., Loewen, P. C., and Ivancich, A. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 15954-15963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeGray, J. A., Gunther, M. R., Tschirret-Guth, R., Montellano, P. R. O. D., and Mason, R. P. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 2359-2362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyagawa, I., Kurita, Y., and Gordy, W. (1960) J. Chem. Phys. 6 1599-1603 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duboc-Toia, C., Hassan, A. K., Mulliez, E., Choudens, S. O.-D., Fontecave, M., Leutwein, C., and Heider, J. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125 38-39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pogni, R., Baratto, M. C., Giansanti, S., Teutloff, C., Verdin, J., Valderrama, B., Lendzian, F., Lubitz, W., Vaszquez-Duhalt, R., and Basosi, R. (2005) Biochemistry 44 4267-4274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bleifuss, G., Kolberg, M., Pötsch, S., Hofbauer, W., Bittl, R., Lubitz, W., Gräslund, A., Lassmann, G., and Lendzian, F. (2001) Biochemistry 40 15362-15368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Box, H. C., and Budzinski, E. E. (1976) J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. II, 553-555

- 49.Kou, W. W. H., and Box, H. C. (1976) J. Chem. Phys. 64 3060-3062 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu, A., Barra, A.-L., Rubin, H., Lu, G., and Gräslund, A. (2000) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122 1974-1978 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dorlet, P., Seibold, S. A., Babcock, G. T., Gerfen, G. J., Smith, W. L., Tsai, A. L., and Un, S. (2002) Biochemistry 41 6107-6114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson, J. C., Wu, G., Tsai, A.-L., and Gerfen, G. J. (2005) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 1618-1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gerfen, G. J., Bellew, B. F., Un, S., Bollinger, J. M., Jr., Stubbe, J., Griffin, R. G., and Singel, D. J. (1993) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 155 6420-6421 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ivancich, A., Dorlet, P., Goodin, D. B., and Un, S. (2001) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123 5050-5058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Un, S., Gerez, C., Elleingand, E., and Fontecave, M. (2001) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123 3048-3054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andersson, K. K., and Barra, A.-L. (2002) Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Spectrosc. 58 1101-1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeschke, G. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1707 91-102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gunther, M. R., Sturgeon, B. E., and Mason, R. P. (2000) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 28 709-719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Svistunenko, D. A., and Cooper, C. E. (2004) Biophys. J. 87 582-595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Un, S. (2005) Magn. Reson. Chem. 43 S229-S236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ivancich, A., Mattioli, T. A., and Un, S. (1999) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 5743-5753 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Farrar, C. T., Gerfen, G. J., Griffin, R. G., Force, D. A., and Britt, R. D. (1997) J. Phys. Chem. B. 101 6634-6641 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Faller, P., Goussias, C., Rutherford, A. W., and Un, S. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 8732-8735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ranguelova, K., Suarez, J., Magliozzo, R. S., and Mason, R. P. (2008) Biochemistry 47 11377-11385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vidossich, P., Alfonso-Prieto, M., Carpena, X., Loewen, P. C., Fita, I., and Rovira, C. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 13436-13446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Putnam, C. D., Arvai, A. S., Bourne, Y., and Tainer, J. A. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 296 295-309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ivancich, A., Jouve, H. M., and Gaillard, J. (1996) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118 12852-12853 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Winterbourn, C. C., Parsons-Mair, H. N., Gebicki, S., Gebicki, J. M., and Davies, M. J. (2004) Biochem. J. 381 241-248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao, X., Yu, S., Ranguelova, K., Suarez, J., Metlitsky, L., Schelvis, J. P. M., and Magliozzo, R. S. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284 7030-7037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.