Abstract

The Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) transcription factor suppresses tumorigenesis in gastrointestinal epithelium. Thus, its expression is decreased in gastric and colon cancers. Moreover, KLF4 regulates both differentiation and growth that is likely fundamental to its tumor suppressor activity. We dissected the expression of Klf4 in the normal mouse intestinal epithelium along the crypt-villus and cephalo-caudal axes. Klf4 reached its highest level in differentiated cells of the villus, with levels in the duodenum > jejunum > ileum, in inverse relation to the representation of goblet cells in these regions, the lineage previously linked to KLF4. In parallel, in vitro studies using HT29cl.16E and Caco2 colon cancer cell lines clarified that KLF4 increased coincident with differentiation along both the goblet and absorptive cell lineages, respectively, and that KLF4 levels also increased during differentiation induced by the short chain fatty acid butyrate, independently of cell fate. Moreover, we determined that lower levels of KLF4 expression in the proliferative compartment of the intestinal epithelium are regulated by the transcription factors TCF4 and SOX9, an effector and a target, respectively, of β-catenin/Tcf signaling, and independently of CDX2. Thus, reduced levels of KLF4 tumor suppressor activity in colon tumors may be driven by elevated β-catenin/Tcf signaling.

Keywords: KLF4, intestine, epithelium, differentiation, Wnt and Sox9

Introduction

The Kruppel-like family of zinc-finger transcription factors (KLFs) regulates a range of biological processes, including cell growth, differentiation, embryogenesis and tumorigenesis [1–3]. A member of this family, KLF4, also known as gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor/GKLF or epithelial/endothelial zinc finger/EZF, is highly expressed in epithelial cells of different tissues [4]. In the intestine, expression of Klf4 appears to be associated primarily with the terminally differentiated state of epithelial cells since by in situ hybridization and immunostaining, Klf4 localizes to the upper region of the colonic crypt of the adult mouse [5, 6].

Although Klf4 has been reported to be expressed in most cells of the upper crypt and villi of the large and small intestine, respectively [6], only mature secretory goblet cells of the colon have been reported to be reduced in mice that have a targeted inactivation of Klf4 [7]. Thus, the broader role that Klf4 may play in the maturation program of other cell types in the intestinal mucosa is not clear. This is important since Klf4 is involved in intestinal tumorigenesis. For example, expression of Klf4 is decreased in intestinal adenomas of ApcMin mice [8] and in colonic adenomas and carcinomas of FAP (familial adenomatous polyposis) patients, [8, 9], consistent with a tumor suppressor role of Klf4 [10, 11]. In fact, deletion of Klf4 in the gastric epithelium induced hyperplasia and polyps in the mouse stomach [12] and it has been shown that haploinsufficiency of this transcription factor promotes the development of intestinal adenomas in ApcMin mice [13]. The mechanism is not understood, but forced expression of KLF4 in vitro caused growth arrest in a p21-dependent manner and repressed the cyclin D1 promoter, leading to cell cycle arrest at the G1/S transition [9, 14, 15]. In addition, ectopic expression of KLF4 induced cell-cycle arrest, thereby reducing tumorigenicity in vivo [16].

Despite this evidence that Klf4 has tumor suppressing activity in the intestine, Klf4 null mice showed no alteration in proliferation in the intestinal mucosa, suggesting that Klf4 modulation of intestinal cell lineage specific differentiation may be highly significant in suppression of tumor formation. In this regard, Wnt signaling also plays a fundamental role in homeostasis and transformation of the intestinal mucosa through its regulation of both proliferation and cell differentiation [17, 18]. In fact, deletion of Tcf4, a principal effector of Wnt signaling, causes a complete loss of proliferating cells in the intestinal crypt with terminal differentiation of the epithelial cells [19]. Further, there is evidence that Wnt signaling is also involved in controlling secretory cell differentiation [20]. Thus, Wnt and Klf4 may interact functionally in the network of signaling pathways that regulate proliferation and differentiation along the crypt-luminal axis.

Here we used both in vivo and in vitro systems to dissect the regulation of KLF4 in intestinal cell maturation and in both the goblet and the absorptive cell lineages, the most prominent cell lineages in the small and large intestine. We determined the level of expression of Klf4 in isolated epithelial cells along both the crypt–luminal and cephalo-caudal axis, and showed that KLF4 expression increased during differentiation along both the absorptive and goblet cell lineages in vitro. We also determined that KLF4 expression linked to intestinal cell maturation is regulated by intestinal crypt transcription factors TCF4 and SOX9, but was independent of CDX2.

Materials and Methods

Fractionation of murine epithelial cells

The sequential isolation of mouse small and large intestinal epithelial cells along the crypt villus axis has been previously described and validated [21–24]. Briefly, nonfasting C57BL/6 mice (16-week-old) were sacrificed by CO2 overdose. The duodenum, jejunum, ileum and colon were removed separately, tied off at one end, everted and filled to distension with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) prior to closing the remaining open end. Each portion of the intestine was incubated with shaking at 37°C for 10 min in 20ml of citrate buffer ( 96 mM NaCl, 1.5mM KCl, 27 mM Na-citrate, 8mM KH2PO4, 5.6 mM Na2HPO4, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), pH 7.3). Duodenum, jejunum and ileum were then transferred in an EDTA buffer (PBS containing 1.5 mM EDTA, and 0.5 mM DTT) to a 37°C shaking incubator and dissociated epithelial cells were collected after each of 4 consecutive incubation steps lasting 10 min (fraction 1), 10 min (fraction 2), 30 min (fraction 3), and 20 min (fraction 4). In the case of the colon, the same protocol was used, but cells were collected after 3 consecutive incubation steps lasting 30 min each. Cells isolated in the resulting fractions were harvested by centrifugation at 1500 rpm at 4°C for 5 min, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Immunohistochemistry

Intestinal and colonic tissues were routinely fixed overnight in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. After dewaxing and hydration, 5µm sections were pretreated with 3% H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature and incubations of primary antibodies were all performed overnight at 4°C. Antigen retrieval was achieved by boiling in 10mM citrate buffer pH 6.0 (30 min). Immunodetection for light microscopy was performed using labeled Polymer-HRP anti-rabbit secondary antibody from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) and 3′,3′-diaminobenzidine hydrochloride (Sigma) as a peroxidase chromogen. The specificity of the reaction was tested by omitting the primary antibody. Nuclei were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin.

Cell culture

All cell lines used in this study are human colon cancer cells. Caco-2 cells and RKO cells were obtained from the ATCC (Rockville MD, USA). HT29 Cl16E cells were obtained from C. Laboisse (INSERM U539, Nantes, France). Stably transfected LS174T with inducible dnTCF4 have been described previously [17]. HT-29cl.16E-SOX9 and HT-29cl.16E-dnSOX9 cells have been described previously [25]. All cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO 2 incubators (Thermo Forma, Marietta, OH, USA), media were supplemented with fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100 units of penicillin and 100 µg of streptomycin per ml) and 10mM HEPES buffer. The medium for LS174T-dnTCF4 cells included 10 µg/ml of blasticidin and 0.5 mg/ml of zeocin, the medium for HT-29cl.16E-SOX9 and HT-29.16E-dnSOX9 cells was supplemented with 5 µg/ml of blasticidin and 0.25 mg/ml of zeocin.

In spontaneous differentiation of Caco-2, the time when cells first reached confluence (by light microscopy) was designated “day 0”. HT29 Cl.16E cells were seeded at a density of 106 cells/ 25cm2 flask (day -3) and used 0, 3, 5, 7, 12 or 17 days after plating. Doxycycline inductions were performed by addition of 1 µg/ml of doxycycline to the culture medium. For butyrate-induced differentiation, cells were treated by addition of 5 mM sodium butyrate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA).

Transient transfections, plasmids and reporter assays

For transient transfections, cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to instructions of the supplier.

SOX9 expression was down-regulated using a final concentration of 100 nM in each well of a pool of four siRNAs directed against the coding region of SOX9 (siGenome smart pool reagent human SOX9 from Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO; catalog number M-021507-00). For siRNA experiments the same final concentration of a non-specific siRNA was used as a control (siCONTROL Non-targeting siRNA Pool from Dharmacon; catalog number D-001206-13).

DNA plasmids were isolated using the PureYield Plasmid Midiprep System from Promega or QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit from QIAGEN (Valencia, CA USA).

N-terminally flagged wild-type SOX9 and C-terminally truncated ΔC206SOX9 (dnSOX9) expression constructs have been described previously [26][27]. pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) vector alone was used as a negative control. 0.1 µg of each construct were used per well (in 24 well plates) for these experiments. Briefly, four different constructs carrying the Klf4 promoter were used in this study. A luciferase reporter was linked in each case to 2200, 1000, 515 or 250 bp of the 5’-flanking region of the murine Klf4 gene (a generous gift from Dr. Yang, Emory University School of Medicine-Atlanta, and Dr. Chen, Boston University School of Medicine); these constructs have been described previously [28][29]. For assays, cells were co-transfected with these luciferase reporter constructs and pRL-TKRenilla luciferase control plasmid. 0.1 µg of each luciferase reporter construct and 0.05 µg of pRL-TKRenilla luciferase control plasmid were used per well (in 24 well plates) for these experiments. Samples were collected 48h post-transfection and Dual luciferase kit (Promega) was used for luciferase measurement and normalization. Triplicates were performed for each experiment and transfection condition.

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

For total protein extraction, cell pellets were homogenized at 4°C in lysis buffer supplemented with a mixture of protease inhibitors (1/100, P8340, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). After quantification of protein (Bio-Rad protein assay, Bio-Rad Laboratories), 100 µg of cellular protein extracts were loaded and resolved on 8% to 15% SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred by electro-blotting onto activated PVDF membranes for immunoblot analysis.

Primary antibody information is provided in Supplementary Materials and Methods. Secondary antibodies were purchased from Amersham Bioscience (anti-rabbit, NA934V) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (anti-mouse, sc-2005, and anti-goat, sc-2350). Blots were developed using the enhanced chemiluminiscence procedure (Amersham Bioscience).

RNA purification, PCR and real time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the Trizol method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Briefly, first-strand cDNA was synthesized using 1 to 5ug total RNA and was reverse-transcribed with 200 units of reverse transcriptase using the Superscript II (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

For real time PCR, cDNA was amplified using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix and the ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Primers (sequences in Supplementary Materials and Methods) were supplied by Sigma-Genosys (The Woodlands, TX, USA). A standard curve was generated by real-time PCR analysis of 5-fold serial dilutions of a standard template DNA. All reactions were carried out in duplicate. Relative values for each PCR product were expressed in arbitrary units as a ratio of the target transcript normalized to human GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean values ± SEM. Values were compared by a Student’s t-test (2 tailed, assuming equal variances) to test for significant differences.

Results

Klf4 is expressed in the differentiated compartment of the intestinal epithelium

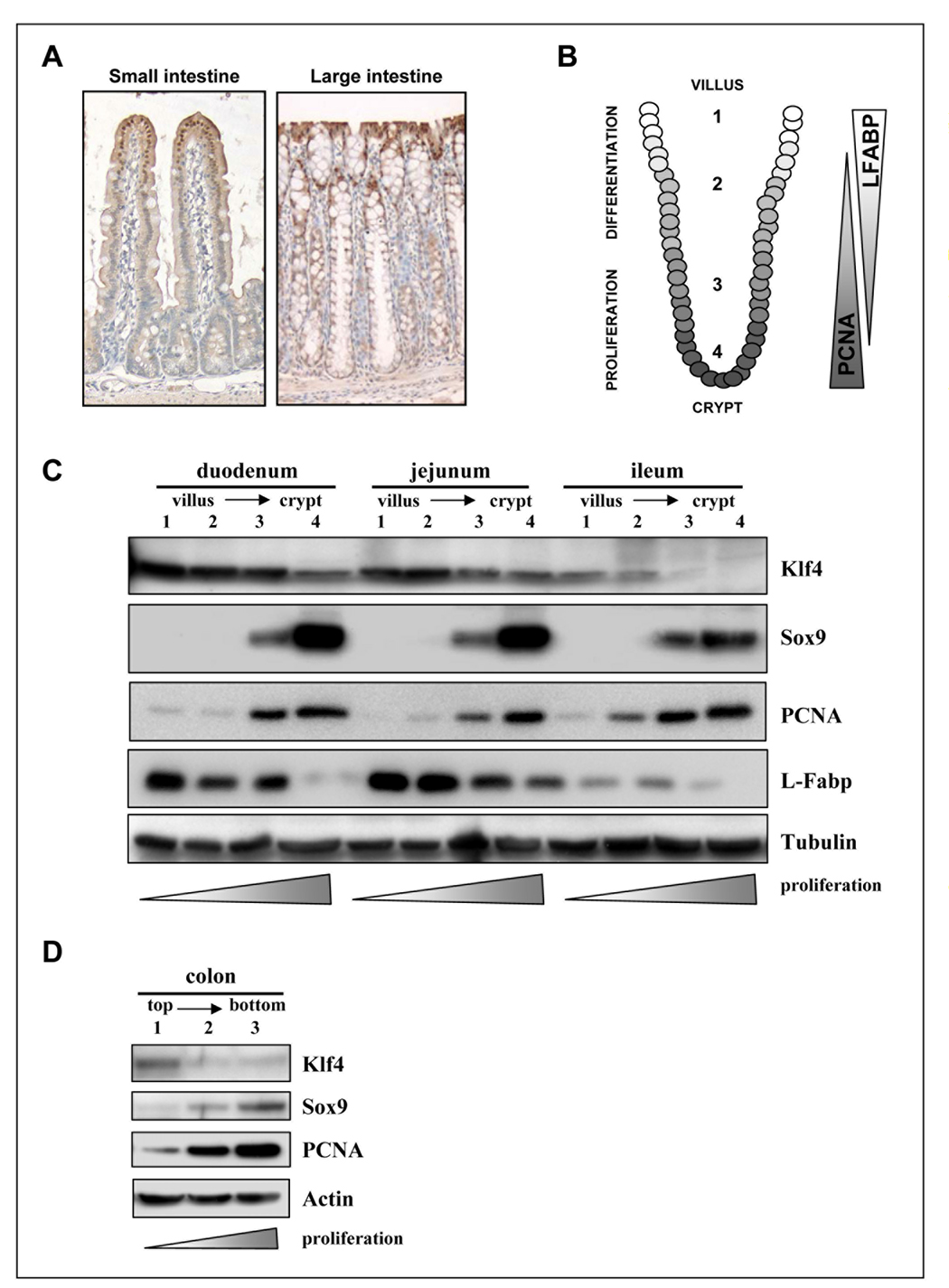

Immunohistochemistry has generally shown Klf4 expression in epithelial cells throughout the intestinal mucosa with an elevated level in the villus and top of the crypt (figure 1A and [6]). To extend these data, we quantified the expression of Klf4 and potentially linked regulatory molecules along both the cephalo-caudal and crypt-lumen axis of the duodenum, jejunum and ileum of mouse intestine. We used a method, previously described and extensively validated by our group [23, 24][30], to fractionate the intestinal epithelium of each of these segments into four fractions, from villus (fraction 1) to crypt (fraction 4) (represented in Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Klf4 is expressed in the villus of the small intestine and in the surface epithelium in large intestine in mouse.

(A) Immunohistochemical staining for Klf4 was performed with the same antibody used in panels C and D (dilution 1:1000) in paraffin-embedded sections of mouse small and large intestines. (B) Schematic representation of the crypt-villus axis in the mature small intestine showing the fractionation of the epithelial cells used from villus (fraction 1), where the proliferating cells are found, to crypt (fraction 4), occupied by differentiated cells. (C) Western blot analysis of Sox9 and Klf4 in mouse intestinal epithelial samples from duodenum, jejunum and ileum fractionated as described above. PCNA and L-Fabp expression was used to monitor the cellular fractionation. Tubulin was used as loading control. (D) Western blot analysis of Sox9 and Klf4 in mouse intestinal epithelial samples from colon fractionated as above. PCNA expression was used to monitor the cellular fractionation. Actin was used as loading control.

The tissue fractionation procedure was monitored by Western blot analysis of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) expression (figure 1C), a marker of proliferation and L-Fabp (liver fatty acid binding protein), a marker of intestinal cell differentiation. PCNA protein levels decreased in a gradient from fraction 4, where it is strongly expressed, to fraction 1, where it is nearly undetectable, consistent with the confinement of proliferating cells to the lower regions (ie fraction 4) of the crypt. In contrast, L-Fabp expression was maximal in the first fractions of the extraction, in the region of the villus where lipids are absorbed [31] and was absent from the proliferating cell compartment (figure 1C).

As observed for PCNA, the transcription factor Sox9 was also largely restricted to the crypt and undetectable in the villus (figure 1C). In contrast, the inverse pattern of expression, similar to that of L-Fabp, was seen for Klf4 protein. Thus, the expression of Klf4 protein is significantly higher in the differentiated compartment than in the proliferative compartment in the mouse intestinal epithelium, and Klf4 and Sox9 showed a reciprocal pattern of expression.

We extended these studies to the large intestine using a similar approach, but in this case, we fractionated the epithelium into three fractions from the top (fraction 1) to the bottom (fraction 3) of the colonic crypts. As shown in figure 1D, PCNA and Sox9 protein levels increased in a gradient from fraction 1 to fraction 3, consistent with the presence of proliferation mainly at the bottom of the crypts. Consistent with the data of figure 1C, the expression of Klf4 was higher in the first fraction enriched in differentiated cells proximal to the mucosal surface. Moreover, the reciprocal expression between Sox9 and Klf4 was also documented in the large intestine (figure 1D).

KLF4 expression increases during spontaneous or NaB-induced differentiation in the HT29cl.16E and Caco2 colon cancer cell lines

While the crypt-luminal pattern of expression of Klf4 was similar in the three parts of the small intestine, there was an overall decrease along the cephalo-caudal axis, with duodenal expression > jejunal > ileal (figure 1C). Since the concentration of goblet cells is higher in the more distal regions of the small intestine (eg ileum), this suggested that the expression of Klf4 is likely not only involved in cells that differentiated along the goblet cell lineage, as has been previously suggested [7]. To pursue this, and to determine whether in vitro models of differentiation recapitulate these patterns of Klf4 expression indicative of a role in cell maturation, we used two human colon carcinoma cell lines, HT-29cl.16E and Caco2, which spontaneously differentiate as goblet and absorptive-like cells, respectively. HT-29cl.16E cells, a clonal derivative of HT29 cells, differentiate into goblet cells upon contact inhibition of growth when maintained in culture over 20 days. This lineage-specific differentiation is characterized by the secretion of mucin, cell polarization, development of tight junctions, and loss of tumorigenicity [32–34]. Caco2 cells, when cultured to confluence, also undergo cell cycle arrest with an accumulation of cells in G0/G1 and a decrease of cells in the S phase of the cell cycle [35]. At 21 days post-confluence, Caco2 cells are maximally differentiated into mature absorptive epithelial cells, both phenotypically and functionally [35–37].

KLF4 mRNA and protein levels were analyzed by real time PCR and western-blot analysis at different time points during 20 or 21 days of culture of HT29cl.16E and Caco2 cells, respectively. As shown in figures 2A and 2B, maximum levels of KLF4 transcripts as well as protein were detected after 20 days of culture in HT29cl.16E (2.3 fold elevation versus day 0 in KLF4 mRNA/GAPDH) and 21 days in Caco2 (7.9 fold elevation versus day 0 in KLF4 mRNA/GAPDH). Although the western-blotting showed differences in molecular weight of KLF4 in HT29cl.16E and Caco2 cells, (~75 kDa and ~50 kDa respectively – see Discussion), protein levels increased in both cell lines to the same extent. Further, the expression of SOX9 decreased in a gradient during differentiation, recapitulating the reciprocal pattern of KLF4 and SOX9 expression observed in vivo (figures 1C and 1D). In addition, the activity of a KLF4 luciferase reporter, in which luciferase expression was driven by a sequence between −1000 and +550 of the 5’ region of the murine KLF4 gene, was up-regulated by 5 fold, and greater than 10 fold, during differentiation of either HT29cl.16E or Caco2 cell lines, respectively (2C and 2D). This established that expression of KLF4 during differentiation was transcriptionally regulated and, most important, that this regulation was present in cells differentiating along either the goblet or the absorptive cell lineages.

Figure 2. KLF4 expression increases in non-proliferating transformed colonic epithelial cells after their spontaneous or butyrate induced differentiation.

Quantification by real-time RT-PCR of KLF4 mRNA levels, and detection of KLF4 and SOX9 proteins by western-blotting, during spontaneous differentiation in HT29cl.16E (A) and Caco2 (B) cells. Data were expressed as fold increased in KLF4/GAPDH mRNA levels of each time point versus non-differentiated cells (day 0). Actin was used as loading control. Columns, mean of at least three different experiments; bars, SE. (C) y (D) A Klf4-luciferase reporter plasmid where Luciferase expression is driven by 1kb of the 5’-flanking region and 550 bp of the 5’-untranslated region of Klf4 was transfected into HT29cl.16E (C) and Caco2 (D) cell lines at the time points indicated in the figures. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined 48 hours after transfection. Columns, mean of at least three different experiments; bars, SE. (E) Quantification by real-time RT-PCR of KLF4 mRNA levels, and detection of KLF4 protein by western-blotting, after butyrate treatment for 72 hours to induce differentiation in HT29cl.16E and Caco2 cells. Data were expressed as KLF4/GAPDH mRNA ratios. Columns, mean of at least three different experiments; bars, SE.

The ability of in vitro systems to recapitulate regulatory events governing KLF4 expression was further investigated using the short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) sodium butyrate (NaB). NaB inhibits cell growth and promotes differentiation characteristic of the absorptive cell phenotype of colon cancer cells [38, 39]. As shown in figure 2E, treatment with 5mM NaB for 72 hrs induced an increase in KLF4 mRNA and protein levels for both HT29cl.16E and Caco2 cells. These data, in addition to the up-regulation of KLF4 expression during differentiation of HT29cl.16E and Caco2 cells (figures 2A–2D), demonstrate that the regulation of KLF4 expression is not lineage restricted.

KLF4 expression is controlled by the transcription factor TCF4

Based on the consistent linkage of elevated KLF4 expression to differentiation of intestinal epithelial cells, we investigated a potential mechanism of regulation of this transcription factor in intestinal epithelial cells by Wnt signaling, a major regulator of proliferation and differentiation in the intestinal epithelium highly active in the progenitor cell population at the base of the crypt. Inhibition of Wnt signaling in colon cancer cells not only blocks proliferation but also induces an intestinal differentiation program and, in fact, many of the genes negatively regulated by TCF4 represent differentiation markers [17, 18]. Therefore, we tested whether KLF4 is regulated by the principal effector of Wnt signaling in the intestinal epithelium, the transcription factor TCF4, using LS174T-dnTCF4 cells, a stable derivative of LS174T colon cancer cells that express dominant-negative TCF4 under the control of a doxycycline-inducible promoter [17] decreasing Wnt-TCF4 signaling upon induction of the cells (Sup. Fig. 1). As shown in figure 3A, KLF4 mRNA levels doubled as soon as 7 hrs following induction of dnTCF4, and progressively increased over 24 to 48 hours, showing a 6–7 fold elevation by 48 hrs. This was paralleled by a strong induction in KLF4 protein expression (figure 3B). Therefore, the transcription factor TCF4 in the LS174T cells down-regulates KLF4 expression, and dnTCF therefore stimulates expression. However, since we did not find a canonical TCF binding sequence (AAGATCAAAGGG) [40, 41] in the 4.0 kb upstream of the KLF4 transcription start site, this regulation may not have depended on direct interaction of TCF4 with the KLF4 promoter.

Figure 3. KLF4 expression is regulated by TCF4 in Ls174T human colon cancer cell line.

(A) Quantification of KLF4 mRNA levels in Ls174T cell line stably transfected with a doxycycline inducible dnTCF4 construct. Real time RT-PCR analysis was performed to quantify KLF4 mRNA levels after 7, 24 and 48 hours of dnTCF4 induction. Data were expressed as fold increase in KLF4/GAPDH mRNA levels of doxycycline treated (dox) versus untreated (ctrl) cells. Time of doxycycline induction is indicated at the bottom of the graph. Columns, mean of duplicates from three different experiments; bars, SE. (B) Detection of the KLF4 protein by western blot in the dnTCF4 stably transfected Ls174T cells with or without doxycycline induction at the indicated time points. Actin served as a loading control.

The transcription factor SOX9 regulates KLF4 in human colon cancer cells

Sox9 has recently been found to be both a target and a modulator of the Wnt signaling pathway [42]. The expression of SOX9 is stimulated by TCF4 and in turn represses the expression of the differentiation markers CDX2 and MUC2 in vitro. Thus, SOX9 is a candidate mediator of Wnt signaling in the maintenance of an undifferentiated, progenitor- cell phenotype in the proliferative compartment of the intestinal epithelium [43]. Therefore, we investigated whether SOX9 also regulates KLF4 expression as a potential intermediate between TCF4 and KLF4 using stably transfected cell lines that, upon induction with doxycycline, express either Flag-tagged wild-type SOX9 (HT-29cl.16E-SOX9) or a Flag-tagged dominant-negative form of SOX9 (HT-29cl.16E-dnSOX9). Both cell lines were grown for 24 and 48 hours, under subconfluent conditions, in the presence and absence of doxycycline. As shown in Sup. Fig. 2, and reported previously [43], changes in CDX2 and MUC2 mRNA levels confirmed the effect of SOX9 and dnSOX9 in these cell lines. Western blot analysis revealed that the level of KLF4 protein significantly decreased after induction of SOX9 expression (figure 4A). This result was consistent with the reciprocal pattern of expression of KLF4 and SOX9 in the mouse intestinal epithelium and in HT29cl.16E and Caco2 cells (figure 1C–D and figure 2A–D). Moreover, the activity of the KLF4 promoter reporter construct (described above) was down-regulated more than 50% by this induction of SOX9 (figure 4B). In contrast, after induction of a dominant- negative form of SOX9 in the HT-29cl.16E-dnSOX9 cell line, KLF4 protein levels increased and the relative luciferase activity obtained with the KLF4-luciferase reporter construct was approximately 5 times higher than in un-induced cells (figure 4C–D).

Figure 4. KLF4 expression is regulated by the transcription factor SOX9.

(A) Western blot analysis of KLF4 in the SOX9 stably transfected HT29cl.16E cells with or without doxycycline induction at the indicated time points. Flag served as a monitor of SOX9 over-expression and actin served as a loading control. (B) Effect of induced SOX9 expression on the Klf4-luciferase reporter activity. A KLF4-luciferase reporter plasmid (described in Figure 2) was transfected into HT29cl.16E-SOX9 for this experiment. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined 48 hours after transfection and culture with or without doxycycline. Columns, mean of five different experiments; bars, SE. ***, p<0.001. (C) Detection of the KLF4 protein by western blot analysis in the dnSOX9 stably transfected HT29cl.16E cells with or without doxycycline induction at the indicated time points. Flag served as a monitor of the dnSOX9 overexpression and actin served as a loading control. (D) Effect of induced dnSOX9 expression on the Klf4-luciferase reporter activity (Klf4-luciferase reporter plasmid described above). Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined 48 hours after transfection and culture with or without doxycycline. Columns, mean of five different experiments; bars, SE. *, p<0.05. (E) Quantification of KLF4 mRNA levels in HT29cl.16E-SOX9 cell line. Real time RT-PCR analysis was performed to quantify KLF4 mRNA levels after 6 and 24 hours of SOX9 induction. Data were expressed as fold increase in KLF4/GAPDH mRNA levels of doxycycline treated (dox) versus untreated (ctrl) cells. Time of doxycycline induction is indicated at the bottom of the graph. Columns, mean of at least three different experiments; bars, SE. (F) Effect of induced SOX9 expression on Klf4-luciferase reporter activity in Caco2 cells. Caco2 cells were cotransfected with an empty vector (ctrl) or the dnSOX9 expression construct, together with Klf4-luciferase reporter (described above). Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined 48 hours after transfection. Columns, mean of three different experiments; bars, SE. **, p<0.01.

Although KLF4 mRNA expression progressively increased over 48 hrs in response to induction of dnTCF4, there was a significant response as soon as 7 hrs following induction (figure 3A). This relatively rapid change in KLF4 expression was also seen in response to SOX9 overexpression, with a decrease in KLF4 detectable by 6 hrs (4E).

These data demonstrated that SOX9 expression is sufficient to decrease the levels of KLF4. Since SOX9 is directly regulated by Wnt signaling, it is a candidate for the bridge between Wnt/TCF4 signaling and down-regulation of KLF4 in proliferating, progenitor intestinal epithelial cells.

To investigate this, we determined if the down-regulation of KLF4 by SOX9 in goblet-like HT-29cl.16E cells (figure 4B) was also seen in absorptive like Caco2 cells, since KLF4 is up-regulated in both goblet-like and absorptive-like differentiation (figure 1). This indeed was the case, since we observed that over-expression of wild-type SOX9 repressed KLF4 by >50% in Caco2 cells (4F). Thus, the modulation of KLF4 by SOX9 occurs in different colon cell lines independently of their final cell fate.

SOX9 and TCF4 have an additive effect on KLF4 expression

The negative regulation of KLF4 by both TCF4 and SOX9, and the fact that TCF4 can regulate SOX9 expression, lead to the hypothesis that this is a linear pathway: TCF4 regulates SOX9 which suppresses KLF4. To investigate this, we silenced SOX9 using siRNA. Figure 5A shows that SOX9 expression was suppressed in LS174T-dnTCF4 cells by approximately 30–50% at 48 to 72 hrs following transfection of SOX9 specific siRNA compared to a non-targeting siRNA. This was sufficient to induce KLF4 mRNA expression by 2–3 fold (figure 5B). When the dnTCF4 was induced in the cells by addition of doxycycline, SOX9 levels decreased and this increased KLF4 expression (figure 5C, lanes 1 and 2). The combination of induction of dnTCF4 and transfection of SOX9 siRNA drove SOX9 levels down by 90% and correspondingly, increased KLF4 expression even further (lane 4 in figures 5C and 5D). This experiment was repeated three times, and quantification demonstrated that there was a reciprocal relationship between mean SOX9 levels and mean KLF4 expression (figure 5D). Linear regression analysis showed this inverse relationship between SOX9 levels and KLF4 expression was statistically significant (figure 5E).

Figure 5. TCF4 and SOX9 have an additive effect on KLF4 regulation.

(A) Quantification of SOX9 mRNA levels in Ls174T-dnTCF4 cell line transfected with either non-targeting (nt) or SOX9 specific (siSOX9) siRNA and grown 48 or 72 hours. (B) Real time RT-PCR analysis was performed to quantify KLF4 mRNA levels in the same experiment described above. Data were expressed as fold increase in SOX9/GAPDH or KLF4/GAPDH mRNA levels of non-targeting versus specific SOX9 siRNA transfected cells. Time is indicated at the bottom of the graph. Columns, mean of duplicates from three different experiments; bars, SE. (C) Detection of KLF4 and SOX9 proteins by western blot in Ls174T-dnTCF4 cells transfected with either non-targeting (nt) -1,2- or SOX9 specific (siSOX9) -3,4- siRNA and grown with -2,4- or without -1,3- doxycycline for 48 hours. (D) Background-adjusted densitometric data (presented as mean values with standard error bar) from 3 independent experiments. (E) Linear regression of densitometric data for KLF4 as a function of SOX9 levels, obtained from the experiments shown in D.

KLF4 regulation by SOX9 is independent of CDX2 activity

KLF4 expression can be dependent on CDX2 activity [29] and, in fact, CDX2 activates a KLF4 promoter that contained a CDX2-binding site beginning at nucleotide position −897 from the start site of transcription [44] (represented by a triangle in Figure 6A). Since SOX9 has been shown to repress CDX2 expression [43], an attractive hypothesis is that SOX9 regulates KLF4 through inhibition of CDX2. To address this, we first determined if the CDX2-binding site present in the KLF4 promoter was required for the regulation of KLF4 by SOX9. Two KLF4-luciferase reporter constructs, KLF4-2200 and KLF4-515, carrying 2200 bp (including the CDX2 binding site) or 515 bp (lacking the CDX2 binding site) length fragments of the murine promoter of KLF4 were transiently transfected into HT-29cl.16E-Sox9 cells and grown under nonconfluent conditions, in the presence or absence of doxycycline for 48 hours. As shown in figure 6A, the CDX2 binding site was not required for the inhibition of KLF4 promoter activity by SOX9 in HT-29cl.16E-SOX9. Additionally, the increase in the KLF4 reporter construct expression in HT-29cl.16E-dnSOX9 cells following induction of the dominant negative form of SOX9 was also not dependent on the presence of the CDX2 site in the reporter construct (Sup. Fig. 3). Therefore, the CDX2 binding site in the KLF4 promoter is not required for the modulation of KLF4 by SOX9. This was confirmed by a third, independent approach. The RKO human colon cancer cell line has an endogenous truncating and inactivating mutation in the CDX2 gene [45]. We transiently co-transfected an empty vector (ctrl) or a dnSOX9 construct into RKO cells, together with the 1000 bp KLF4-luciferase reporter construct described previously. As shown in figure 6B, the expression of the dominant-negative form of SOX9 in the CDX2 deficient RKO cell line strongly increased the activity of the KLF4 promoter by over 6 fold, similar to the increase seen in the HT-29cl.16E-dnSOX9 cell line (figure 4D), despite the absence of a functional CDX2 gene in these cells. Thus, CDX2 is not necessary for repression of KLF4 promoter activity by SOX9.

Figure 6. KLF4 regulation by the transcription factor SOX9 is independent of CDX2 in human colon cancer cells.

(A) KLF4-luciferase reporter activity of KLF4-2200 and KLF4-515 in HT29cl.16E cells stably transfected with the doxycycline inducible SOX9 construct. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined 48 hours after transfection with or without doxycycline (ctrl). Columns, mean of four different experiments; bars, SE. (B) Effect of induced dnSOX9 expression on KLF4- luciferase reporter activity in RKO cells that carry an inactive CDX2 form. RKO cells were co-transfected with an empty vector (ctrl) or the dnSOX9 construct, together with Klf4-luciferase reporter (described in Figure 2). Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined 48 hours after transfection. Columns, mean of three different experiment; bars, SE. **, p<0.01.

Discussion

We analyzed increased expression of Klf4 in the differentiated cell compartments of the villi of the small intestine and nearer the surface of the crypts of the large intestine in the mouse. This pattern of expression of Klf4 was recapitulated in colonic tumor epithelial cells after their spontaneous or butyrate induced differentiation along either the goblet cell or the absorptive cell lineages. We also confirmed that Wnt signaling (eg TCF4) suppresses KLF4 expression [17, 28, 46], and demonstrated that this requires SOX9 induction by Wnt signaling. Thus, a network is established that links Wnt signaling in the intestinal mucosa to KLF4 repression through effects of TCF4 on SOX9 expression. This explains our observation, and that of others [6, 9, 43], of a reciprocal pattern of expression of KLF4 and SOX9 along the crypt-villus axis.

The mechanism by which SOX9 regulates KLF4 expression is likely not through direct interaction of SOX9 with the KLF4 promoter for three reasons: first, a characteristic of all Sox proteins is their dependence on other transcription factors as partners for efficient target gene activation [47, 48]; second, the smallest fragment of the KLF4 promoter that responded after SOX9 or dnSOX9 expression in our study does not contain an optimal SOX9 or general SOX consensus sequence (AGAACAATGG or (A/T)(A/T)CAA(A/T)G) [49]; third, SOX9 has been described as a transcriptional activator [50, 51], but not as a transcriptional repressor.

CDX2 is a target of Wnt signaling through SOX9 [43, 45] and had been reported to regulate KLF4 expression [29]. However, our data demonstrated that this transcription factor was not necessary for KLF4 regulation by SOX9 in RKO cells, where a truncation mutation renders CDX2 inactive, and our experimental elimination of a CDX2 binding site in the promoter of KLF4 did not change its activity in cells forced to express either SOX9 or a dnSOX9 (figures 6A and supplementary figure 3, respectively). This is also consistent with the fact that Klf4 was not altered significantly in the gastric epithelia of Cdx2 transgenic mice [12]. As an alternative, we identified a predicted E-box site and 3 different Sp1 sites present in the smallest fragment of the Klf4 promoter (KLF4-250) inducible by dnSOX9 overexpression. We mutated these four predicted binding sites, but there were similar increases in Klf4 promoter activity among the wildtype and the mutant forms in response to expression of dnSOX9 (Sup. Fig 4), thereby likely eliminating a role of these Sp1 or E-box binding sites in negative regulation of the KLF4 promoter by SOX9. Thus, the mechanisms by which SOX9 regulates KLF4 and what binding partners are required for it are not yet clear.

Dissection of the function and regulation of Klf4 in different cell lineages in the intestine is important because Klf4 has been shown to have significant tumor suppressor activity, demonstrated by an increase in tumors in the ApcMin mouse caused by Klf4 haploinsufficiency. This was accompanied by an increase in β-catenin and cyclin D1 activity [13], and KLF4 repression of β-catenin/TCF signaling has also been shown in HT29 colon carcinoma cells [28, 46]. However, we have not detected altered β-catenin/TCF signaling activity in HT29cl.16E and Caco2 cells after siRNA suppression, or forced overexpression, of KLF4 (not shown). Thus, KLF4 modulation of β-catenin-TCF4 signaling may be context dependent.

More generally, the tumor suppressor function of KLF4 may be linked to its regulation of differentiation and/or proliferation. This issue is complicated by the difficulty in experimentally dissociating differentiation from altered proliferation. However, we found that while decreased KLF4 expression increased cyclin D1 promoter activity in HT29cl.16E and Caco2 cells (Sup. Fig. 5), this was not sufficient to alter the proliferation of the cells (Sup. Fig. 6). Similarly, in Klf4 null mice, a decrease in the cdk inhibitor p21Waf1/cip1 did not change cell proliferation in the intestine [7], and we have shown that the increase in Apc initiated tumors in mice with a targeted inactivation of p21 was linked to a decrease in goblet cell differentiation [52]. Thus, the increase in KLF4 expression during differentiation and its ability to regulate p21 suggest that KLF4 may suppress tumor formation primarily through its role in intestinal cell differentiation. However, in contrast to other reports, our results suggest that the function of KLF4 is not restricted to intestinal cells differentiating along the goblet cell lineage. In the mouse small intestine, we found that the expression of Klf4 decreased from the duodenum to the ileum. In contrast, goblet cell number and abundance of small intestinal goblet cell markers (eg mucins) increase from the duodenum to the distal ileum in normal intestine [53]. In addition, the expression of TFF3 and MUC2, two goblet cell markers, decrease in response to butyrate treatment in several colon cancer cells [54, 55] in contrast to the increase in KLF4 we demonstrated in response to butyrate. Further, we also showed that KLF4 increased during spontaneous and butyrate induced differentiation in HT29cl.16E and Caco2 cells, and was regulated by SOX9, independently of the lineage to which the cells were committed. In this regard, KLF4 regulates expression of genes that are differentiation-specific, but not goblet cell specific, such as alkaline phosphatase [56], villin 2, and several keratins [57]. In addition, despite the differences in molecular weight of KLF4 in HT29cl.16E and Caco2 cells, KLF4 specific siRNA reduced each of these bands to the same extent. Moreover, analysis of the genomic locus of KLF4 from each cell line, revealed no differences and, as stated earlier, silencing of KLF4 in the two cell lines increased cyclin D1 expression (Sup. Fig. 5). Thus, the significance of the differences in molecular weight in the two cell lines remains to be determined.

In summary, we have analyzed the increased expression of Klf4 in vivo as epithelial cells migrate and differentiate along the crypt-villus axis. We established that KLF4 expression is regulated similarly during intestinal cell maturation in vitro along either the goblet cell or the absorptive cell lineage. Our data extend our understanding of the network of signaling pathway interactions in maintaining an undifferentiated, pluripotent cell phenotype in the proliferating compartment of the intestinal epithelium, with Wnt signaling repressing KLF4 through both the transcription factors TCF4 and SOX9.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Lidija Klampfer, Anna Velcich, John Mariadason and Barbara Heerdt for their suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants RO1 CA114265, U54 CA100926, PO 13330, and a postdoctoral fellowship to Marta Flandez from the Spanish Ministerio de Educacion y Ciencia.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Suske G, Bruford E, Philipsen S. Mammalian SP/KLF transcription factors: bring in the family. Genomics. 2005;85:551–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black AR, Black JD, Azizkhan-Clifford J. Sp1 and kruppel-like factor family of transcription factors in cell growth regulation and cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2001;188:143–160. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaczynski J, Cook T, Urrutia R. Sp1- and Kruppel-like transcription factors. Genome Biol. 2003;4:206. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-2-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrett-Sinha LA, Eberspaecher H, Seldin MF, de Crombrugghe B. A gene for a novel zinc-finger protein expressed in differentiated epithelial cells and transiently in certain mesenchymal cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31384–31390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields JM, Christy RJ, Yang VW. Identification and characterization of a gene encoding a gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor expressed during growth arrest. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20009–20017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McConnell BB, Ghaleb AM, Nandan MO, Yang VW. The diverse functions of Kruppel-like factors 4 and 5 in epithelial biology and pathobiology. Bioessays. 2007;29:549–557. doi: 10.1002/bies.20581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz JP, Perreault N, Goldstein BG, Lee CS, Labosky PA, Yang VW, Kaestner KH. The zinc-finger transcription factor Klf4 is required for terminal differentiation of goblet cells in the colon. Development. 2002;129:2619–2628. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dang DT, Bachman KE, Mahatan CS, Dang LH, Giardiello FM, Yang VW. Decreased expression of the gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor gene in intestinal adenomas of multiple intestinal neoplasia mice and in colonic adenomas of familial adenomatous polyposis patients. FEBS Lett. 2000;476:203–207. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01727-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shie JL, Chen ZY, O'Brien MJ, Pestell RG, Lee ME, Tseng CC. Role of gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor in colonic cell growth and differentiation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G806–G814. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.4.G806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei D, Gong W, Kanai M, Schlunk C, Wang L, Yao JC, Wu TT, Huang S, Xie K. Drastic down-regulation of Kruppel-like factor 4 expression is critical in human gastric cancer development and progression. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2746–2754. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao W, Hisamuddin IM, Nandan MO, Babbin BA, Lamb NE, Yang VW. Identification of Kruppel-like factor 4 as a potential tumor suppressor gene in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:395–402. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz JP, Perreault N, Goldstein BG, Actman L, McNally SR, Silberg DG, Furth EE, Kaestner KH. Loss of Klf4 in mice causes altered proliferation and differentiation and precancerous changes in the adult stomach. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:935–945. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghaleb AM, McConnell BB, Nandan MO, Katz JP, Kaestner KH, Yang VW. Haploinsufficiency of Kruppel-like factor 4 promotes adenomatous polyposis coli dependent intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7147–7154. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Johns DC, Geiman DE, Marban E, Dang DT, Hamlin G, Sun R, Yang VW. Kruppel-like factor 4 (gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor) inhibits cell proliferation by blocking G1/S progression of the cell cycle. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30423–30428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101194200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowland BD, Bernards R, Peeper DS. The KLF4 tumour suppressor is a transcriptional repressor of p53 that acts as a context-dependent oncogene. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1074–1082. doi: 10.1038/ncb1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dang DT, Chen X, Feng J, Torbenson M, Dang LH, Yang VW. Overexpression of Kruppel-like factor 4 in the human colon cancer cell line RKO leads to reduced tumorigenecity. Oncogene. 2003;22:3424–3430. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van de Wetering M, Sancho E, Verweij C, de Lau W, Oving I, Hurlstone A, van der Horn K, Batlle E, Coudreuse D, Haramis AP, Tjon-Pon-Fong M, Moerer P, van den Born M, Soete G, Pals S, Eilers M, Medema R, Clevers H. The beta-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell. 2002;111:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mariadason JM, Bordonaro M, Aslam F, Shi L, Kuraguchi M, Velcich A, Augenlicht LH. Down-regulation of beta-catenin TCF signaling is linked to colonic epithelial cell differentiation. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3465–3471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korinek V, Barker N, Moerer P, van Donselaar E, Huls G, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Depletion of epithelial stem-cell compartments in the small intestine of mice lacking Tcf-4. Nat Genet. 1998;19:379–383. doi: 10.1038/1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinto D, Gregorieff A, Begthel H, Clevers H. Canonical Wnt signals are essential for homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1709–1713. doi: 10.1101/gad.267103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiser MM. Intestinal epithelial cell surface membrane glycoprotein synthesis. I. An indicator of cellular differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:2536–2541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferraris RP, Villenas SA, Diamond J. Regulation of brush-border enzyme activities and enterocyte migration rates in mouse small intestine. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:G1047–G1059. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.262.6.G1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mariadason JM, Nicholas C, L'Italien KE, Zhuang M, Smartt HJ, Heerdt BG, Yang W, Corner GA, Wilson AJ, Klampfer L, Arango D, Augenlicht LH. Gene expression profiling of intestinal epithelial cell maturation along the crypt-villus axis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1081–1088. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smartt HJ, Guilmeau S, Nasser SV, Nicholas C, Bancroft L, Simpson SA, Yeh N, Yang W, Mariadason JM, Koff A, Augenlicht LH. p27(kip1) Regulates cdk2 Activity in the Proliferating Zone of the Mouse Intestinal Epithelium: Potential Role in Neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:232–243. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jay P, Berta P, Blache P. Expression of the carcinoembryonic antigen gene is inhibited by SOX9 in human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2193–2198. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Santa Barbara P, Bonneaud N, Boizet B, Desclozeaux M, Moniot B, Sudbeck P, Scherer G, Poulat F, Berta P. Direct interaction of SRY-related protein SOX9 and steroidogenic factor 1 regulates transcription of the human anti-Mullerian hormone gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6653–6665. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sudbeck P, Schmitz ML, Baeuerle PA, Scherer G. Sex reversal by loss of the C-terminal transactivation domain of human SOX9. Nat Genet. 1996;13:230–232. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stone CD, Chen ZY, Tseng CC. Gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor regulates colonic cell growth through APC/beta-catenin pathway. FEBS Lett. 2002;530:147–152. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03449-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dang DT, Mahatan CS, Dang LH, Agboola IA, Yang VW. Expression of the gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor (Kruppel-like factor 4) gene in the human colon cancer cell line RKO is dependent on CDX2. Oncogene. 2001;20:4884–4890. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guilmeau S, Flandez M, Bancroft L, Sellers RS, Tear B, Stanley P, Augenlicht LH. Intestinal Deletion of Pofut1 in the Mouse Inactivates Notch Signaling and Causes Enterocolitis. Gastroenterology. 2008 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shields HM, Bates ML, Bass NM, Best CJ, Alpers DH, Ockner RK. Light microscopic immunocytochemical localization of hepatic and intestinal types of fatty acid-binding proteins in rat small intestine. J Lipid Res. 1986;27:549–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Augeron C, Laboisse CL. Emergence of permanently differentiated cell clones in a human colonic cancer cell line in culture after treatment with sodium butyrate. Cancer Res. 1984;44:3961–3969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Augenlicht LH, Augeron C, Yander G, Laboisse C. Overexpression of ras in mucus-secreting human colon carcinoma cells of low tumorigenicity. Cancer Res. 1987;47:3763–3765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laboisse C, Bogomoletz WV. [Mucines: glycoproteins in search of recognition] Ann Pathol. 1989;9:175–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mariadason JM, Rickard KL, Barkla DH, Augenlicht LH, Gibson PR. Divergent phenotypic patterns and commitment to apoptosis of Caco-2 cells during spontaneous and butyrate-induced differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2000;183:347–354. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200006)183:3<347::AID-JCP7>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hara A, Hibi T, Yoshioka M, Toda K, Watanabe N, Hayashi A, Iwao Y, Saito H, Watanabe T, Tsuchiya M. Changes of proliferative activity and phenotypes in spontaneous differentiation of a colon cancer cell line. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1993;84:625–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1993.tb02022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hidalgo IJ, Raub TJ, Borchardt RT. Characterization of the human colon carcinoma cell line (Caco-2) as a model system for intestinal epithelial permeability. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:736–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthews JB, Hassan I, Meng S, Archer SY, Hrnjez BJ, Hodin RA. Na-K-2Cl cotransporter gene expression and function during enterocyte differentiation. Modulation of Cl- secretory capacity by butyrate. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2072–2079. doi: 10.1172/JCI1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnard JA, Warwick G. Butyrate rapidly induces growth inhibition and differentiation in HT-29 cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1993;4:495–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Beest M, Dooijes D, van De Wetering M, Kjaerulff S, Bonvin A, Nielsen O, Clevers H. Sequence-specific high mobility group box factors recognize 10–12-base pair minor groove motifs. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27266–27273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004102200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van de Wetering M, Cavallo R, Dooijes D, van Beest M, van Es J, Loureiro J, Ypma A, Hursh D, Jones T, Bejsovec A, Peifer M, Mortin M, Clevers H. Armadillo coactivates transcription driven by the product of the Drosophila segment polarity gene dTCF. Cell. 1997;88:789–799. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81925-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bastide P, Darido C, Pannequin J, Kist R, Robine S, Marty-Double C, Bibeau F, Scherer G, Joubert D, Hollande F, Blache P, Jay P. Sox9 regulates cell proliferation and is required for Paneth cell differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:635–648. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blache P, van de Wetering M, Duluc I, Domon C, Berta P, Freund JN, Clevers H, Jay P. SOX9 is an intestine crypt transcription factor, is regulated by the Wnt pathway, and represses the CDX2 and MUC2 genes. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:37–47. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahatan CS, Kaestner KH, Geiman DE, Yang VW. Characterization of the structure and regulation of the murine gene encoding gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor (Kruppel-like factor 4) Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4562–4569. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.23.4562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.da Costa LT, He TC, Yu J, Sparks AB, Morin PJ, Polyak K, Laken S, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. CDX2 is mutated in a colorectal cancer with normal APC/beta-catenin signaling. Oncogene. 1999;18:5010–5014. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang W, Chen X, Kato Y, Evans PM, Yuan S, Yang J, Rychahou PG, Yang VW, He X, Evers BM, Liu C. Novel cross talk of Kruppel-like factor 4 and beta-catenin regulates normal intestinal homeostasis and tumor repression. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2055–2064. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2055-2064.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamachi Y, Uchikawa M, Kondoh H. Pairing SOX off: with partners in the regulation of embryonic development. Trends Genet. 2000;16:182–187. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01955-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wegner M. Secrets to a healthy Sox life: lessons for melanocytes. Pigment Cell Res. 2005;18:74–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2005.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mertin S, McDowall SG, Harley VR. The DNA-binding specificity of SOX9 and other SOX proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1359–1364. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.5.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panda DK, Miao D, Lefebvre V, Hendy GN, Goltzman D. The transcription factor SOX9 regulates cell cycle and differentiation genes in chondrocytic CFK2 cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41229–41236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu S, Guo R, Quarles LD. Cloning and characterization of the proximal murine Phex promoter. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3987–3995. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.9.8403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang WC, Mathew J, Velcich A, Edelmann W, Kucherlapati R, Lipkin M, Yang K, Augenlicht LH. Targeted inactivation of the p21(WAF1/cip1) gene enhances Apc-initiated tumor formation and the tumor-promoting activity of a Western-style high-risk diet by altering cell maturation in the intestinal mucosal. Cancer Res. 2001;61:565–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Specian RD, Oliver MG. Functional biology of intestinal goblet cells. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:C183–C193. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.260.2.C183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tran CP, Familari M, Parker LM, Whitehead RH, Giraud AS. Short-chain fatty acids inhibit intestinal trefoil factor gene expression in colon cancer cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G85–G94. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.1.G85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Augenlicht L, Shi L, Mariadason J, Laboisse C, Velcich A. Repression of MUC2 gene expression by butyrate, a physiological regulator of intestinal cell maturation. Oncogene. 2003;22:4983–4992. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hinnebusch BF, Siddique A, Henderson JW, Malo MS, Zhang W, Athaide CP, Abedrapo MA, Chen X, Yang VW, Hodin RA. Enterocyte differentiation marker intestinal alkaline phosphatase is a target gene of the gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G23–G30. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00203.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen X, Whitney EM, Gao SY, Yang VW. Transcriptional profiling of Kruppel-like factor 4 reveals a function in cell cycle regulation and epithelial differentiation. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:665–677. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01449-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.