Abstract

The present research examined whether people feel happier and healthier when they feel more understood in daily social interactions. A two-week diary study showed that people reported greater life satisfaction and fewer physical symptoms on days in which they felt more understood by others. Moreover, we found that individuals who tend to see themselves in relations to others (i.e., women or those scored high on interdependent self-construal measure) showed a stronger association between daily felt understanding and daily life satisfaction or physical symptoms. These findings demonstrate that daily social experiences, such as felt understanding, are associated with daily well-being, particularly for individuals with greater interdependent self-construal.

A Swedish proverb says “shared joy is a double joy; shared sorrow is half a sorrow.” This folk wisdom succinctly explains the hedonic benefits of interacting with others who understand our thoughts and feelings. Supporting the link between being understood and feeling good, research shows that happy people tend to have high quality social relationships (Diener & Seligman, 2002), and these relationships are sustained in part by being with others who understand and respond to one’s needs and values (Reis, Clark & Holmes, 2004). The present research builds on these notions by asking (a) whether feeling understood in daily social interactions directly relates to two aspects of daily well-being1, namely daily life satisfaction and daily physical symptoms, and (b) whether this association is stronger for those who consider their social relationships a central part of the self.

People enjoy social environments where they feel understood by others. According to self-verification theory, people prefer to interact with others who confirm their self-views, even when those views are negative (see Swann, Rentfrow, & Guinn, 2003 for a review). People also feel more satisfied and stay in relationships longer when they and their partners have similar affective responses to life events (Anderson, Keltner, & John, 2003; Oishi & Sullivan, 2006) or similar interpersonal goals (Sanderson & Evans, 2001). These findings imply that people seek and enjoy social interactions with others who understand their subjective thoughts and feelings. This collection of research also presents an emerging perspective that feeling understood or misunderstood is an integral experience of our social lives.

Although research has successfully demonstrated the role of felt understanding in maintaining social relationships (Reis et al., 2004), knowledge regarding its impact on other important outcomes such as daily well-being is limited. Research on close relationships and social support predicates that people should feel happier and healthier when they are surrounded by others who understand their needs and values. For example, people experience greater positive affect when they feel that their partner understands them (Oishi, Koo, & Akimoto, 2008) and shares their joy for positive life events (Gable, Reis, Impett & Asher, 2004). Perceiving close others to be responsive and understanding of a stressful experience mitigates its negative impact on one’s health and subjective well-being (Sarason, Sarason, & Gurung, 1997). These findings suggest that people’s sense of daily well-being may fluctuate as a function of how much they feel understood by others in their social interactions.

The experience of being understood or misunderstood may be most related to daily well-being among individuals who consider their social relationships a central aspect of the self (Cross, Bacon, & Morris, 2000; Singelis, 1994). People who tend to see themselves in terms of group affiliations and interpersonal relationships (interdependent self-construal) may feel particularly satisfied when they are understood by others, but they also risk feeling worse when they are misunderstood. Felt understanding may indicate how well these individuals are relating to others, which determines their happiness. Previous research showed that people who value social relationships feel happier when they have more satisfying social interactions (Oishi, Diener, Suh, & Lucas, 1999), and feel more satisfied about an interaction when they perceive the interaction partner as understanding and responsive (Cross et al., 2000). This evidence suggests that individual differences in interdependent self-construal should moderate the extent to which daily experiences of felt understanding are tied to daily well-being. In contrast, those who see themselves as autonomous and independent individuals (independent self-construal) may be less sensitive to being understood and misunderstood, and thus their daily well-being should be less susceptible to fluctuations in these experiences.

In addition to individual differences, a considerable amount of research shows cultural and gender differences in interdependent and independent self-construal (Cross & Madson, 1997; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). On average, Asians and women are more likely to have an interdependent self-construal than European Americans and men are, respectively. If interdependent self-construal moderates the relationship between felt understanding and daily well-being, we may also find this relationship to be stronger among Asians and women than among European Americans and men.

Using a daily diary methodology, the present research examined whether people’s daily well-being, indicated by daily life satisfaction and daily physical symptoms, corresponds to their experience of being understood by others in social interactions. We expected daily felt understanding to be positively associated with daily life satisfaction and negatively associated with daily physical symptoms. Moreover, this association may be particularly stronger among individuals who tend to see themselves in relation to others. Finally, we also hypothesized that the positive benefit of felt understanding may extend to the following day.

Method

Participants

One hundred and twenty-eight undergraduates (92 female, 36 male) at the University of Virginia participated in the study to receive partial course credit. Ninety participants identified themselves as White/Caucasian (70.3%) and 38 identified themselves as Asian. Participants’ demographic information was collected at the beginning of the semester, when they registered into the department-wide participant pool system.

Procedure and Measures

Participants completed all questionnaires online. They were first directed to complete a one-time online questionnaire via e-mail. After providing informed consent, participants completed a battery of personality measures that included the 24-item independent and interdependent self-construal scale (Singelis, 1994). On a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), participants responded to items such as “My happiness depends on the happiness of those around me” and “It is important for me to maintain harmony within my group” that assessed interdependent self-construal (M = 4.77, SD = 0.75, Cronbach’s α = .77). They also responded to items such as “I enjoy being unique and different from others in many respects” and “I am comfortable with being singled out for praise or rewards” that assessed independent self-construal (M = 4.60, SD = 0.74, Cronbach’s α = .74). The two subscales were correlated at .40, and the averages did not differ by gender or ethnicity.

After completing this initial questionnaire, participants received another e-mail that directed them to the online daily diary questionnaire. In the subsequent 13 days, participants received a reminder every evening asking them to complete the same survey. Compliance was excellent. Five percent of the total entries were completed on the following day before noon. On average, participants completed 13.81 daily surveys (SD = 1.07).

The daily survey included questions about participants’ life satisfaction and physical symptoms, as well as questions about felt understanding/misunderstanding. Daily life satisfaction was assessed with two items (Oishi, 2002): “How was today?” (1 = horrible, 7 = excellent) and “How satisfied are you with your life today?” (1 = extremely dissatisfied, 7 = extremely satisfied). Because these items were correlated highly, r = .76, p < .001, they were averaged to create a single daily life satisfaction score (M = 4.82, SD = 1.18). We also generated a lagged score to indicate life satisfaction of the following day, which allows us to examine whether feelings of being understood or misunderstood predict next day life satisfaction.

Daily physical symptoms were assessed by the Emmons’ (1992)14-item physical symptom checklist (e.g., headaches, faintness/dizziness, and stomachache/pain). We created a daily physical symptom score by summing the number of symptoms participants checked, ranging from 0 to 14. Participants reported an average of 1.47 symptoms per day (SD = 1.68). Daily physical symptoms was negatively related to daily life satisfaction with an average correlation of −.23 (SD = .31). As with daily life satisfaction, we also created a lagged physical symptom score.

Toward the end of the survey, participants indicated the degree to which they felt understood and misunderstood by others by responding to “During your interaction with others today, to what extent did you feel understood by others?” (M = 4.94, SD = 1.23) followed by “And, to what extent did you feel misunderstood by others?” (M = 2.68, SD = 1.29) on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 7 = a lot; adapted from Oishi et al., 2008). On average, these two items were correlated at −.38 (SD = .37) across individuals over the 14 days.

Results

We examined whether felt understanding and misunderstanding in daily social interactions were associated with daily well-being at the within-person level, and whether this within-person association was moderated by participants’ interdependent and independent self-construal, ethnicity, and gender. We used HLM 6.04 (Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2007) to analyze our data, which consisted of two levels. In the Level 1 model, daily life satisfaction or daily physical symptoms was predicted by daily felt understanding and misunderstanding and an error term. Daily felt understanding and misunderstanding were centered on an individual’s mean (i.e., group-centering). At Level 2, interdependent and independent self-construal scores, ethnicity (White = 0, Asian = 1), and gender (Male = 0, Female = 1) were centered and entered simultaneously to predict the intercept and coefficients at Level 1 (See the HLM model below).

Level-1 model:

Level-2 model:

Daily life satisfaction

Consistent with our prediction, people had greater life satisfaction on days when they felt more understood, γ10 = .40, t(123) = 12.99, p < .001, and less misunderstood by others, γ20 = −.10, t(123) = −4.19, p < .001. Moreover, daily felt misunderstanding was more strongly associated with daily life satisfaction among women than men, γ24 = −.19, t(123) = −3.48, p = .0013. (See Table 1). For every one-point increase in daily felt misunderstanding, a female participant’s life satisfaction score decreased by 0.29-point from her average life satisfaction score. In contrast, the daily life satisfaction of a male participant decreased only by 0.10-point. There was no direct relationship between interdependent self-construal and average daily life satisfaction, γ01 = .14, t(123) = 1.58, p = .12. Independent self-construal was positively associated daily life satisfaction, γ02 = .31, t(123) = 3.06, p = .001, but this measure did not moderate the relationship between daily felt understanding and daily life satisfaction.

Table 1.

Estimations of daily life satisfaction and health symptoms as a function of felt understanding, self-construal, ethnicity and gender

| Life Satisfaction |

Health Symptoms |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same day | Next day | Same day | Next day | |

| Intercept (γ00) | 4.81 | 4.82 | 1.46 | 1.38 |

| Interdependence (γ01) | .14 | .13 | .25 | .25 |

| Independence (γ02) | .31** | .32** | −.12 | −.08 |

| Ethnicity (γ03) | −.25* | −.24 | −.32 | −.36 |

| Gender (γ04) | −.02 | .03 | .44 | .41 |

| Felt understanding (γ10) | .40** | .03 | −.14** | −.10** |

| Interdependence (γ11) | .01 | −.05 | −.08 | −.13** |

| Independence (γ12) | .05 | .04 | −.04 | −.04 |

| Ethnicity (γ13) | −.04 | .02 | −.02 | .01 |

| Gender (γ14) | −.11 | −.02 | .02 | .05 |

| Felt misunderstanding (γ20) | −.10** | −.00 | .06 | .02 |

| Interdependence (γ21) | .04 | −.07 | −.05 | −.09 |

| Independence (γ22) | −.03 | .04 | −.00 | −.02 |

| Ethnicity (γ23) | −.01 | .02 | −.05 | −.10 |

| Gender (γ24) | −.19** | .09 | .02 | .03 |

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .05

Daily Physical Symptoms

We conducted the same HLM analysis with daily physical symptoms as the outcome variable. Similar to daily life satisfaction, participants who felt more understood in their social interactions reported fewer daily physical symptoms, γ10 = −.14, t(123) = −3.46, p = .001. Although women and those with higher interdependent self-construal reported somewhat more daily physical symptoms on average, γ04 = .44, t(123) = 1.91, p = .058 and γ01 = .25, t(123) = 1.68, p = .096 respectively, there was no moderating effect of gender, ethnicity or self-construal on the relationship between daily felt understanding/misunderstanding and daily physical symptoms (See Table 1). Feelings of being misunderstood were not related to daily physical symptoms, γ20 = .06, t(123) = 1.32, p = .1894.

Life Satisfaction on the Following Day

Next we conducted a series of time-lag analyses to examine the spill-over effect of felt understanding and misunderstanding on daily life satisfaction. First, we replaced the outcome variable with the lagged score and we did not find any relationships among variables. Then, we repeated the analysis controlling for life satisfaction on the previous day at Level 1 such that Day t+1 life satisfaction was predicted from Day t life satisfaction, Day t felt understanding, and Day t felt misunderstanding. Participants who were satisfied on Day t continued to be more satisfied on the next day, γ30 = .12, t(123) = 3.80, p < .001. There were no other reliable effects.

Physical Symptoms on the Following Day

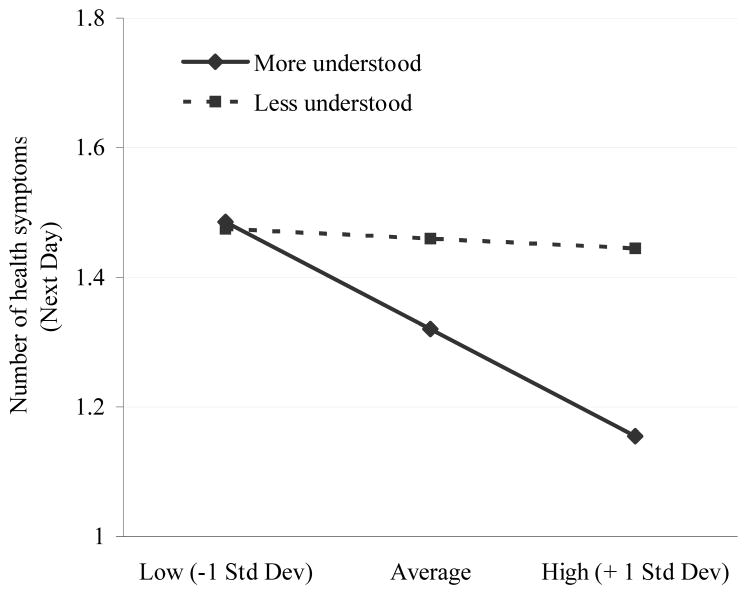

With respect to the number of physical symptoms participants reported on the following day, participants who felt more understood on a particular day reported fewer physical symptoms the following day, γ10 = −.10, t(123) = −2.67, p = .009. More importantly, interdependent self-construal moderated the link between felt understanding and physical symptoms on the following day, γ11 = −.13, t(123) = −2.48, p = .015. Specifically, people higher in interdependent self-construal reported fewer physical symptoms when they felt more understood the day before. (See Figure 1). Unlike feelings of being understood, feelings of being misunderstood neither directly related to the number of physical symptoms on the subsequent day, γ20 = .02, t < 1, p > .50, nor did interdependent self-construal, gender and ethnicity moderate the association between felt misunderstanding and physical symptoms on the following day5.

Figure 1.

Number of health symptoms in the following day by feelings of being understood and interdependent self-construal.

Finally, we repeated the analysis controlling for the number of physical symptoms on the previous day. Not surprisingly, participants who had more physical symptoms the day before also had more symptoms the following day, γ30 = .21, t(123) = 6.73, p < .001 and the main effect of felt understanding decreased to −.06, t(123) = −1.72, p = .088. However, interdependent self-construal remained as a moderator of the relationship between felt understanding and physical symptoms, γ21 = −.12, t(123) = −2.40, p = .018.

Discussion

Over two weeks, participants reported their daily life satisfaction, daily physical symptoms and daily experience of being understood and misunderstood. People reported higher life satisfaction and fewer physical symptoms on days when they felt more understood by others. Moreover, two additional findings provide support that daily felt understanding and daily well-being are more closely related among individuals who consider social relationships an important aspect of the self. First, women’s daily life satisfaction decreased more sharply than men’s did when they felt misunderstood. Because women tend to have a more relational-interdependent self-construal (Cross et al., 2000), this is consistent with our prediction that felt misunderstanding can be more detrimental to life satisfaction for those who place a greater emphasis on social relationships in their self-concepts. Second, individuals with greater interdependent self-construal reported fewer physical symptoms after they reported being more understood in their previous day social interactions. These findings converge to suggest that fluctuations in daily well-being correspond to daily experiences of felt (mis)understanding, particularly for those who value social relationships as an important part of who they are.

It is somewhat puzzling that we found different effects with different indicators of interdependence. In particular, we found that gender moderated the relationship between daily felt misunderstanding and daily life satisfaction but interdependent self-construal moderated the relationship between daily felt understanding and daily physical symptoms. Although both findings are consistent with our hypothesis, it is not obvious why one factor relates to felt understanding while another relates to felt misunderstanding. We suspect that this difference may be due to conceptual differences in interdependence as relational or collectivistic. Previous research suggests that the interdependence of women tends to be more relational than men (Gabriel & Gardner, 1999). Therefore, for women, interpersonal understanding may be seen as the default state of any relationship, whereas misunderstanding may be more of an anomaly. As such, women’s daily well-being may be more affected by misunderstanding than understanding.

In contrast, the measure of interdependent self-construal may capture more of a collectivistic rather than relational view of the self (Kashima, Yamaguchi, Kim, Choi, Gelfand, & Yuki, 1995). People who tend to see themselves in a collectivistic way may be more attuned to being understood because it facilitates group cohesiveness and the achievement of group goals. Hence, interdependent self-construal is more likely to moderate the relationship between felt understanding and daily well-being. Furthermore, we expected Asians, whose self-construal has been shown to be more collectivistic than that of European Americans’ (e.g., Markus & Kitayama, 1991), to show a stronger association between felt understanding and well-being, but this was not what we found. The data did not show any difference in interdependent and independent self-construals between the two ethnic groups. This lack of difference might account for the null findings with respect to ethnicity.

It is worth noting that the correlational nature of the present study allows another interpretation; that is, greater daily life satisfaction and fewer physical symptoms lead to greater felt understanding. Our reliance on similarly scaled self-report measures does not help to clarify the bi-directional nature of these variables. However, one can imagine that different processes may be involved in the different interpretations, and future research can help elucidate the interrelation of these variables by examining these processes. For example, felt understanding may contribute to life satisfaction because it increases self-esteem, or life satisfaction may increase sociability, which in turn increases the likelihood of feeling understood. Finally, future research should consider obtaining a more representative sample when examining the questions above.

While folk wisdom and scientific knowledge concur that having satisfying relationships is important for health and happiness, we have only a rudimentary understanding of the processes by which successful social interactions promote well-being. The present research suggests that felt understanding or the lack thereof may be an important factor in understanding how happy relationships influence happiness and health, particularly for those with greater interdependent self-construal. Future research is encouraged to expand this line of work because of its important implications for refining our understanding of how healthy social relationships are translated into well-being for different individuals.

Acknowledgments

This research was in part supported by the National Institute of Mental Health research grant R01-MH066857. We thank Erin Whitchurch for providing comments on this manuscript.

Footnotes

In the current research, daily well-being is indicated by daily life satisfaction and daily physical symptoms. For the sake of brevity, the term “daily well-being” refers to these two indicators throughout the paper.

The error variance of each outcome variable is estimated. Approximately 33% of the variability of daily life satisfaction and 45% of the variability of health symptoms is due to inter-individual differences (Level 2). The proportion of variance across the two levels was similar for the lagged scores (33% at Level 2 for one-day lagged life satisfaction, 49% at Level 2 for one-day lagged health symptoms).

Effect size was estimated based on error variance explained by the variables at each level. For same day life satisfaction, felt understanding measures reduced 24% of error variance (ε) in the Level 1 model. Gender, race, and self-construal measures reduced 18% of the intercept error variance (η0) and 63% of the misunderstanding slope error variance (η2).

The felt understanding measures at Level 1 explained 5% of error variance (ε) of health symptoms.

Felt understanding measures at Level 1 explained 4% of error variance (ε) of following day health symptoms. Level 2 variables explained 9% of the intercept error variance (η0) and 68% of the understanding slope error variance (η1).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson C, Keltner D, John OP. Emotional convergence between people over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1054–1068. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Seligman MEP. Very happy people. Psychological Science. 2002;13:81–84. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, Madson L. Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122:5–37. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, Bacon PL, Morris ML. The relational-interdependent self-construal and relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:791–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons R. Abstract vs. concrete goals: Personal striving level, physical illness and psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:292–300. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.62.2.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable SL, Reis HT, Impett EA, Asher ER. What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:228–245. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel S, Gardner WL. Are there “his” and “her” types of interdependence? The implications of gender differences in collective and relational interdependence for affect, behavior, and cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;75(3):642–655. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.3.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima Y, Yamaguchi S, Kim U, Choi SC, Gelfand MJ, Yuki M. Culture, gender, and self: A perspective from individualism-collectivism research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:925–937. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98:224–253. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S, Diener E, Suh E, Lucas RE. Value as a moderator in subjective well-being. Journal of Personality. 1999;67:157–184. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S, Koo M, Akimoto S. Culture, interpersonal perceptions, and happiness in social interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34:307–320. doi: 10.1177/0146167207311198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S, Sullivan HW. The predictive value of daily vs. retrospective well-being judgments in relationship stability. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2006;42:460–470. [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Clark MS, Holmes JG. Perceived partner responsiveness as an organizing construct in the study of intimacy and closeness. In: Mashek DJ, Aron AP, editors. Handbook of closeness and intimacy. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 201–225. [Google Scholar]

- Singelis TM. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1994;20:580–591. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson CA, Evans SM. Seeing one’s partner through intimacy-colored glasses: An Examination of the processes underlying the intimacy goals –relationship satisfaction link. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:463–473. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Gurung RAR. Close personal relationships and health outcomes: A key to the role of social support. In: Duck S, editor. Handbook of personal relationships. 2. New York: Wiley; 1997. pp. 547–573. [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB, Jr, Rentfrow PJ, Guinn J. Self-verification: The search for coherence. In: Leary M, Tangney J, editors. Handbook of self and identity. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 367–383. [Google Scholar]