Abstract

Crucial steps in tumor growth and metastasis are proliferation, survival and neovascularization. Previously, we have demonstrated that receptors for CXCL-8, CXCR1 and CXCR2, are expressed on endothelial cells and CXCR2 has been shown to be a putative receptor for angiogenic chemokines. In this report, we examined whether tumor angiogenesis and growth of CXCL-8-expressing human melanoma cells are regulated in vivo by a host-CXCR2-dependent mechanism. We generated mCXCR2−/−, mCXCR2+/− and wild type (WT) nude mice following crosses between BALB/c mice heterozygous nude+/− and heterozygous for mCXCR2+/−. We observed a significant inhibition of human melanoma tumor growth and experimental lung metastasis in mCXCR2−/− mice as compared to WT nude mice. Inhibition in tumor growth and metastasis was associated with a decrease in melanoma cell proliferation, survival, inflammatory response and angiogenesis. Together, these studies demonstrate the importance of host CXCR2-dependent CXCL-8-mediated angiogenesis in the regulation of melanoma growth and metastasis.

Keywords: CXCR2, Melanoma, Metastasis

Introduction

Although melanoma is a disease that affects only 4% of persons afflicted with skin cancer, it is one of the leading causes of malignancy-related mortality in the U.S. During 2008, it is estimated that 62,480 new cases of melanoma will be diagnosed in the United States, and 8,420 people will die due to this devastating disease (1). Due to the high mortality associated with this disease, management requires an in-depth understanding of the biology of this complex disease.

The expression of CXCL-8 in melanoma has been shown to correlate positively with disease progression (2, 3). The aggressiveness of malignant melanoma is attributed, in part, to the expression of CXCL-8 and its receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 (4). In addition to melanoma cells, both CXCR1 and CXCR2 are expressed on endothelial cells and neutrophils (5, 6). Analysis of CXCR2 in human melanoma specimens demonstrated that CXCR2 is expressed predominantly by higher grade melanoma tumors and metastases, suggesting an association between expression of CXCL-8 and CXCR2 in advanced lesions and metastases (4). Previous reports from our laboratory and others have demonstrated that CXCR1 and CXCR2, are expressed on endothelial cells (7-9) and CXCR2 has been shown to play a role in angiogenesis, as it has been shown to be a putative receptor for angiogenic chemokines (5, 10). In this report, we hypothesized that tumor angiogenesis and growth in CXCL-8-expressing melanoma cells are regulated in vivo by a host-mCXCR2-dependent mechanism. We observed a significant inhibition of human melanoma tumor growth and experimental lung metastasis in mCXCR2−/− mice as compared to WT mice. Inhibition in tumor growth and metastasis was associated with decrease in melanoma cell proliferation, survival, inflammatory response and angiogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

BALB/c mice heterozygous for nude+/− or heterozygous for mCXCR2+/− were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice that lack an intact mIL-8Rh (mouse homologue of human IL-8 receptor/mCXCR2) gene, were originally developed by gene targeting with a vector constructed by deleting the single exon containing the 350-amino acid open reading frame of the murine IL-8 receptor [which has 68% and 71% amino acid identity with human IL-8 receptors A (CXCR1) and B (CXCR2)] (11). We generated mCXCR2−/− nude mice following crosses between BALB/c mice heterozygous for nude+/− and heterozygous for mCXCR2+/−. Mice were housed and handled according to protocols approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Genotyping using allele-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and mRNA analysis

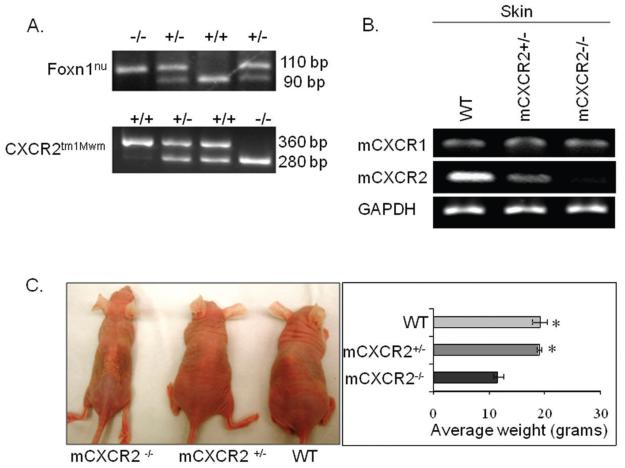

Each mouse was genotyped (a representative gel picture shown in Figure 1A) using mouse tail DNA and amplified for CXCR2tm1Mwm using CXCR2 wild type primers (GGT CGT ACT GCG TAT CCT GCC TCA G and TAG CCA TGA TCT TGA GAA GTC CAT G), which amplify a 360 bp fragment of the wild type allele and for the inserted neomycin gene using primers (CTT GGG TGG AGA GGC TAT TC and AGG TGA GAT GAC AGG AGA TC), which amplify a 280 bp fragment. Furthermore, to confirm the nude background, DNA was amplified for Foxn1nu using primers (GGC CCA GCA GGC AGC CCA AG and AGG GAT CTC CTC AAA GGC TTC), which amplified a 168 bp fragment of the wild type and mutant alleles. Subsequently, 10 ul of amplified product was digested in a 20 ul volume with BseDI, which digests the Foxn1nu allele to 110 and 58 bp products and the wild type allele to 90 bp, 53 bp and 20 bp. Absence of a band at 110 bp indicated a wild type genotype and the presence of bands at 110 bp and 90 bp indicated a heterozygous genotype (Figure 1A). Average size and weight of mCXCR2−/− nude mice were lower as compared to the age matched WT and mCXCR2 +/− nude mice (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Generation of CXCR2 knockout mice.

Genotyping of nude CXCR2 mice by RT-PCR analysis (A). For confirmation of the nude background, F2 progeny DNA was amplified for Foxn1nu (upper panel) as described in material and methods. In lower panel the 360 bp PCR product represents the wild type allele (lane 1), 360 bp and 280 bp fragments represent heterozygous alleles (lane 2 & 3), and the 280 bp product represents the knockout allele ( lane 4). B. Expression of mCXCR1 at mRNA level was consistent in WT, mCXCR2+/− and mCXCR2−/− nude mice whereas, expression mCXCR2 was reduced in mCXCR2+/− and completely knocked down in mCXCR2−/− nude mice. C. Average size and weight of mCXCR2−/− mice were lower as compared to age matched mCXCR2+/− and WT nude mice.

mCXCR1 and mCXCR2 mRNA expression in skin was determined in all three types of mice by semi-quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) as described earlier (12) using the following primers: mCXCR1, 5′-AAT CTG TTG TGG CTT CAC CCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCT ATC TTC CGC CAG GCA TAT-3′ (reverse); mCXCR2, 5′-GCT GTC GTC CTT GTC TTC C-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCC TTG TCA ATG TCA TCG C-3′ (reverse); GAPDH, 5′-CGC ATT TGG TCG TAT TGG G-3′ (forward), and 5′-TGA TTT TGG AGG GAT CTC GC-3′ (reverse) (Figure 1B). PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 10 min; 35 cycles of 95 °C for 45 s, 60 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1 min. PCR fragments were separated on a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (0.25 μg/ml) and visualized and analyzed using the Alpha Imager gel documentation system (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Cell culture and reagents

A375SM, a highly metastatic human melanoma cell line was maintained in culture in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% L-glutamine, 1% vitamin solution (MediaTech, Herndon, VA), and gentamycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cultures were maintained for no longer than 4 weeks after recovery from frozen stocks.

In vivo tumor growth and experimental lung metastasis

Tumor growth was examined by subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of A375SM cells (1 × 106 cells/0.1 ml of HBSS) into WT, mCXCR2+/− or mCXCR2−/− nude mice. Tumor growth was monitored twice a week, and tumor volume was calculated by the following formula: volume = π/6 × (smaller diameter)2 × (larger diameter). Animals were sacrificed and tumor tissues were harvested and processed for histochemical analysis. To examine experimental lung metastasis, A375SM cells (1×106 cells/0.1 ml of HBSS) were injected intravenously (i.v.) into WT, mCXCR2+/− or mCXCR2−/− nude mice. Mice were sacrificed 8-weeks following tumor cell injection and their lungs harvested and fixed in Bouin's solution. Lung metastatic nodules were counted under a dissecting microscope.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunostaining was performed as described previously (4) using antibodies: mouse monoclonal anti-PCNA (1:40; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rat anti-mouse GR-1 (1:50; Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc. Birmingham, AL) and mouse biotinylated GS-IB4 (isolectin from Griffonia simplicifolia; 1:50; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Tumor cell apoptosis was measured using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL). Briefly, tumor sections were deparaffinized by incubation in EZ-Dewax (Biogenex, San Roman, CA) and rinsed in diH2O to remove residual EZ-Dewax. Sections were blocked for 30 minute and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with the respective biotynalated secondary antibodies (1:500 in PBS) was incubated for 45 min except for GS-IB4 at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was visualized by incubation with avidin-biotin complex and diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride substrate (Vector Laboratories). The sections were observed and stained cells and vessels were counted microscopically (Nikon E400 microscope) using a 5×5 reticle grid (Klarmann Rulings, Litchfield, NH).

Statistical analysis

All the values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences between the groups were compared using unpaired two-tailed t-test using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). In vivo analysis was performed using Mann-Whiney U-test for significance. A p value of equal or less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Knockdown of mCXCR2 decreased human melanoma growth and experimental lung metastasis

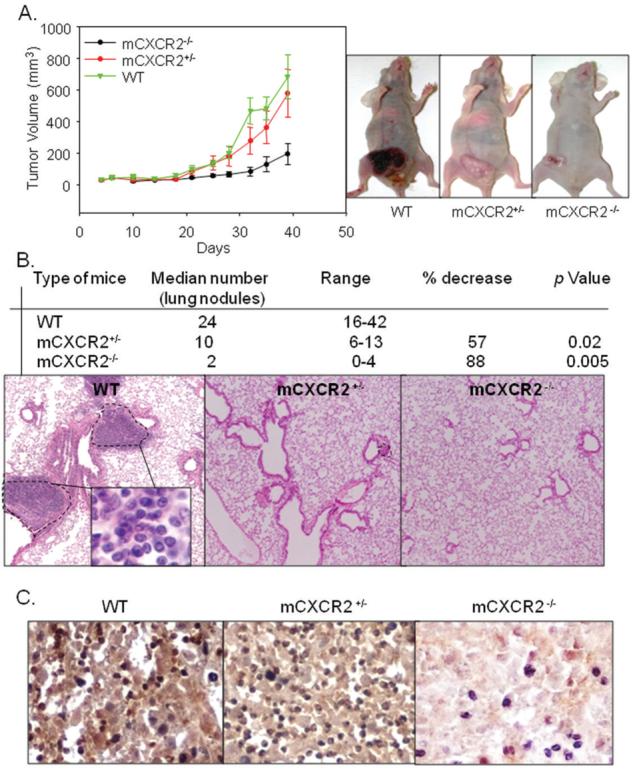

To examine the role of host CXCR2 in melanoma growth, nude mice (WT, mCXCR2+/− or mCXCR2−/−) were s.c. injected with A375SM cells. Tumor size was measured over a 6 week period. We observed a significant inhibition in melanoma growth in mCXCR2−/− and mCXCR2+/− mice as compared with the WT mice (Figure 2A). mCXCR2+/− mice showed lower melanoma growth kinetics as compared to WT and higher as compared to mCXCR2−/− mice, suggesting that the host mCXCR2 levels may be critical in melanoma growth.

Figure 2. Melanoma growth and experimental lung metastasis in CXCR2 knockout mice.

A375SM cells (1 × 106 in 0.1 ml of HBSS) cells were s.c. injected into the flank of nude mice. Tumor volume was measured twice weekly with a caliper and tumor volume calculated. Tumor growth was significantly decreased (p<0.05) in mCXCR2−/− nude mice as compared to WT nude mice. Results are shown as mean tumor volume ± SEM (A). Average number of lung nodules of mCXCR2−/− and mCXCR2+/− mice were significantly lower as compared to WT nude mice (B). A representative picture of immunohistochemical staining for lung metastases in WT nude mice at 200X has been shown (C).

In the next set of experiments, we examined the role of host mCXCR2 in melanoma metastasis. For experimental lung metastasis, A375SM cells were injected i.v. into WT, mCXCR2+/− or mCXCR2−/− nude mice. We found a significantly lower median number and size of metastatic lung nodules in mCXCR2−/− as compared to mCXCR2+/− and WT mice (Figure 2B). We also confirmed the levels of mCXCR2 in tumors obtained from all three groups of mice (Figure 2C).

Knockdown of host mCXCR2 inhibits human melanoma proliferation, survival and angiogenesis

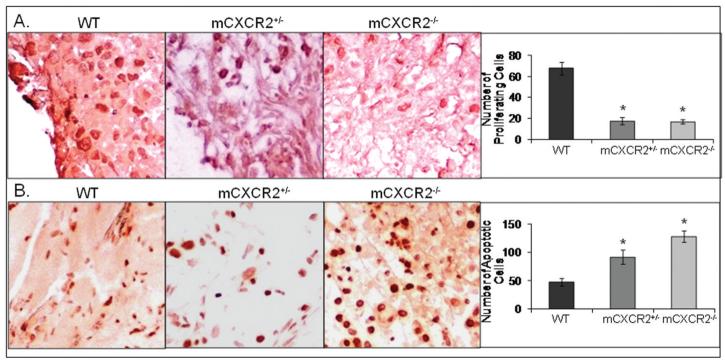

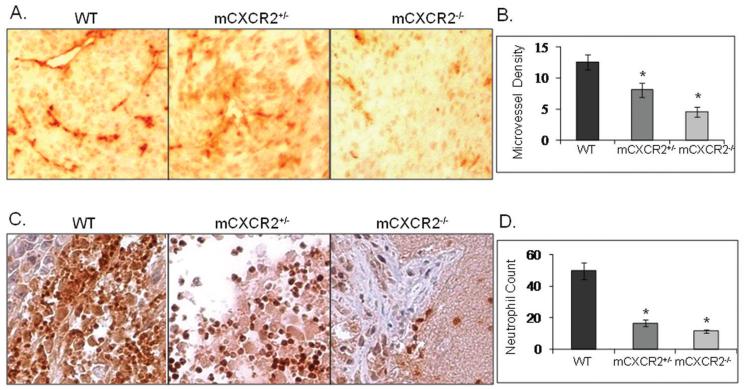

To further assess the mechanism for reduced melanoma growth and metastasis in mCXCR2−/− mice, we next examined cellular proliferation, survival and angiogenesis in tumors from mCXCR2−/−, mCXCR2+/− and WT nude mice. Cellular proliferation was analyzed by PCNA immunostaining of tumor sections which showed a significant decrease in PCNA positive cells in tumors obtained from mCXCR2−/− and mCXCR2+/− nude mice as compared to WT nude mice (Figure 3A). To examine apoptosis in tumors, TUNEL immunostaining of tumor sections was performed. We observed a significant increase in TUNEL positive cells in tumors from mCXCR2−/− and mCXCR2+/− nude mice as compared to tumors in WT mice (Figure 3B). Microscopic examination of tumor tissue immunostained for blood vessels showed a significantly lower numbers of microvessels in tumors from mCXCR2−/− and mCXCR2+/− mice as compared to tumors from WT nude mice (Figure 4A). On an average, tumors from mCXCR2−/− and mCXCR2+/− showed a 64.3% and 35.7% reduction in the number of blood vessels as compared to the tumors from WT nude mice (Figure 4B). Together, these data demonstrate that host CXCR2 is necessary for malignant cell proliferation, survival and neovascularization.

Figure 3. Decreased proliferation and survival in tumors from mCXCR knockout mice.

Immunohistochemical staining for PCNA (A) and TUNEL (B) was analyzed as described in “Material and Methods”. Stained cells were counted in ten arbitrarily selected fields at 200X magnification in a double-blinded manner and are expressed as average number of immunostained cells per field view. *, p<0.05.

Figure 4. Inhibition in neovascularization and neutrophil infiltration in tumors from mCXCR2 knockout mice.

Immunohistochemical staining for microvessel (A) using GS-IB4 and neutrophils (C) using mouse GR-1 was analyzed as described in material and methods. Microvessel density (B) and neutrophils (D) were quantitated microscopically with a 5×5 reticle grid at 400X magnification. The values are average number of immunostained positive cells ± SEM. *p<0.05. The representative pictures shown are at 200X.

Reduced tumor-induced inflammatory response in mCXCR2 (−/−) nude mice

CXCR2-deficient mice have been shown to have a deficiency in neutrophil recruitment following inflammation (13). We examined the importance of host CXCR2 on tumor induced inflammatory response by examining neutrophil infiltration in tumor tissue using GR-1 immunohistochemistry. Neutrophil infiltration in tumors from mCXCR2−/− nude mice was greatly reduced (Figure 4B) as compared to the tumors from WT nude mice. Quantification of neutrophil infiltration demonstrated a significant (3.0 - 4.3 fold decrease) difference in the neutrophil population in tumors from mCXCR2−/− and mCXCR2+/− nude mice as compared with tumors from WT nude mice (Figure 4D).

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate that host mCXCR2 plays an important role in melanoma growth and metastasis. The decrease in tumor growth and experimental lung metastasis in mice that lack mCXCR2 expression was associated with a decrease in melanoma cell proliferation, survival, inflammation and angiogenesis.

CXCR2 is expressed by vascular endothelial cells and is the primary functional chemokine receptor in mediating endothelial cell chemotaxis in response to CXCL-8 (5). We have shown that CXCL-8, a CXCR2 ligand induces endothelial cell tube formation and inhibits apoptosis in endothelial cells via CXCR1 and CXCR2 (8). Therefore, the fact that tumor growth was inhibited in mCXCR2−/− mice suggests the importance of host CXCR2 as a key determinant of melanoma angiogenesis, growth and experimental lung metastasis. Additional support is provided by the observation that tumors in mCXCR2−/− mice had decreased tumor cell proliferation and survival, suggesting the importance of host CXCR2 expression in regulation of phenotypes associated with melanoma growth and experimental lung metastasis.

Our data suggest that loss of at least one allele of host CXCR2 has a greater impact on the ability of melanoma cells to metastasize than it does on tumor growth. Melanoma growth in mCXCR2+/− mice was slower as compared to the growth in WT animals, but not significantly different. However, we observed a significant inhibition of experimental lung metastasis in mCXCR2+/− animals as compared to WT animals. These data suggest organ site dependent CXCL-8-CXCR2 signaling in melanoma growth and metastasis. A previous study demonstrated that melanoma growing in the skin microenvironment expressed significantly higher levels of CXCL-8 as compared to the lung microenvironment (14), which can impact CXCL-8-mCXCR2 dependent responses. In addition, our data clearly demonstrate that loss of both alleles of host CXCR2 further inhibited melanoma growth in the skin microenvironment and experimental lung metastasis.

Previous reports have suggested a role for the CXCL-8-CXCR2 axis in melanoma angiogenesis (4). We hypothesized that this process might be diminished in mCXCR2−/− mice. Our results demonstrate tumor angiogenesis was decreased in mCXCR2−/− and mCXCR2+/− mice compared with WT nude mice. These results are in agreement with another report where in the absence of CXCR2 on host endothelial cells within the tumor, tumor-associated angiogenesis was markedly reduced (15). Similarly, attenuation of CXCR2 activity has been shown to inhibit angiogenesis and tumor growth (16).

Our data demonstrated a diminished inflammatory response as observed by decreased neutrophil infiltration in tumors in mCXCR2−/− mice. CXCR2 is the major mediator of neutrophil migration to sites of inflammation in addition to its angiogenic effect (17, 18). Mice that lacked an intact mIL-8-Rh (mouse homologue of human IL-8 receptor/mCXCR2) gene, had a loss of neutrophil chemotactic response and intracellular calcium flux to mMIP2 and hIL-8/CXCL8 (11, 19), suggesting that mCXCR2 is the primary (or only) chemokine receptor for these ligands on mouse neutrophils. In the present study, we have compared neutrophil infiltration in tumors from WT and mCXCR2+/− with mCXCR2−/− nude mice. Our results show that mCXCR2−/− mice had minimal neutrophil infiltration in tumors. The decrease in neutrophil infiltration in tumors from mCXCR2−/− mice and their inability to respond to tumors-derived CXCL-8 in turn decreases melanoma neovascularization, tumor growth and metastasis in a paracrine manner. Neutrophils have been shown to play a role in promoting metastatic phenotype of tumors releasing CXCL-8 (20).

In summary, our results suggest that host CXCR2 plays a critical role in melanoma growth, angiogenesis and experimental lung metastasis. We have observed that loss of host CXCR2 (endothelial cells and inflammatory cells) has a significant effect on melanoma growth, angiogenesis and experimental lung metastasis. Hence, targeting the expression of host CXCR2 may represent a potential target for therapeutic intervention in CXCR2-ligand producing malignant tumors.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants CA72781 (R.K.S.), and Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA036727) from National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and Nebraska Research Initiative Molecular Therapeutics Program (R.K.S.). We thank Dr. Ajay P Singh, University of Nebraska Medical Center, NE; for careful reading of this manuscript.

Reference List

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh RK, Gutman M, Radinsky R, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Expression of interleukin 8 correlates with the metastatic potential of human melanoma cells in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3242–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ugurel S, Rappl G, Tilgen W, Reinhold U. Increased serum concentration of angiogenic factors in malignant melanoma patients correlates with tumor progression and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:577–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varney ML, Johansson SL, Singh RK. Distinct expression of CXCL8 and its receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 and their association with vessel density and aggressiveness in malignant melanoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:209–16. doi: 10.1309/VPL5-R3JR-7F1D-6V03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Addison CL, Daniel TO, Burdick MD, Liu H, Ehlert JE, Xue YY. The CXC chemokine receptor 2, CXCR2, is the putative receptor for ELR+ CXC chemokine-induced angiogenic activity. J Immunol. 2000;165:5269–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis I, Dewald B, Geiser T, Moser B, Baggiolini M. Platelet factor 4 binds to interleukin 8 receptors and activates neutrophils when its N terminus is modified with Glu-Leu-Arg. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3574–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salcedo R, Resau JH, Halverson D, Hudson EA, Dambach M, Powell D. Differential expression and responsiveness of chemokine receptors (CXCR1-3) by human microvascular endothelial cells and umbilical vein endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2000;14:2055–64. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0963com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li A, Dubey S, Varney ML, Dave BJ, Singh RK. IL-8 directly enhanced endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and matrix metalloproteinases production and regulated angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2003;170:3369–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li A, Varney ML, Valasek J, Godfrey M, Dave BJ, Singh RK. Autocrine role of interleukin-8 in induction of endothelial cell proliferation, survival, migration and MMP-2 production and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2005;8:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s10456-005-5208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heidemann J, Ogawa H, Dwinell MB, Rafiee P, Maaser C, Gockel HR. Angiogenic Effects of Interleukin 8 (CXCL8) in Human Intestinal Microvascular Endothelial Cells Are Mediated by CXCR2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8508–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cacalano G, Lee J, Kikly K, Ryan AM, Meek S, Hultgren B. Neutrophil and B cell expansion in mice that lack the murine IL-8 receptor homolog. Science. 1994;265:682–4. doi: 10.1126/science.8036519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadanandam A, Varney ML, Kinarsky L, Ali H, Mosley RL, Singh RK. Identification of functional cell adhesion molecules with a potential role in metastasis by a combination of in vivo phage display and in silico analysis. OMICS. 2007;11:41–57. doi: 10.1089/omi.2006.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston RA, Mizgerd JP, Shore SA. CXCR2 is essential for maximal neutrophil recruitment and methacholine responsiveness after ozone exposure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L61–L67. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00101.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutman M, Singh RK, Xie K, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Regulation of IL-8 expression in human melanoma cells by the organ environment. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2470–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mestas J, Burdick MD, Reckamp K, Pantuck A, Figlin RA, Strieter RM. The role of CXCR2/CXCR2 ligand biological axis in renal cell carcinoma. J Immunol. 2005;175:5351–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keane MP, Belperio JA, Xue YY, Burdick MD, Strieter RM. Depletion of CXCR2 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis in a murine model of lung cancer. J Immunol. 2004;172:2853–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terkeltaub R, Baird S, Sears P, Santiago R, Boisvert W. The murine homolog of the interleukin-8 receptor CXCR-2 is essential for the occurrence of neutrophilic inflammation in the air pouch model of acute urate crystal-induced gouty synovitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:900–9. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<900::AID-ART18>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benelli R, Albini A, Noonan D. Neutrophils and angiogenesis: potential initiators of the angiogenic cascade. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2003;83:167–81. doi: 10.1159/000071560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J, Cacalano G, Camerato T, Toy K, Moore MW, Wood WI. Chemokine binding and activities mediated by the mouse IL-8 receptor. J Immunol. 1995;155:2158–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larco JE, Wuertz BR, Furcht LT. The potential role of neutrophils in promoting the metastatic phenotype of tumors releasing interleukin-8. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4895–900. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]