Abstract

Carotenoids are a complex class of isoprenoid pigments playing diverse roles in plants and providing nutritional value. Metabolic engineering of the biosynthetic pathway has been of interest to specifically address global vitamin A deficiency by breeding cereal crop staples in the Poaceae (Grass family) for elevated levels of provitamin A carotenoids. However, there remain open questions about the rate-controlling steps that limit predictability of metabolic engineering in plants, whether by transgenic or nontransgenic means. We decided to focus on the first committed biosynthetic step which is mediated by phytoene synthase. Our studies revealed that in the Grasses, PSY is encoded by three genes. Maize transcript profiling, together with carotenoid and ABA analysis, revealed that the three PSY copies have subfunctionalized and provide the Grasses with a fine tine control of carotenogenesis in response to various developmental and external cues. Promoter analysis supports subfunctionalization; cis-element analysis of maize PSY1 alleles and comparison with Grass orthologs suggests that man's selection of yellow maize endosperm has occurred at the expense of a change of gene regulation in photosynthetic tissue as compared to the progenitor white endosperm PSY1 allele.

Key words: carotenoid biosynthesis, phytoene synthase, gene subfunctionalization, ABA, abiotic stress, transcriptional regulation

Carotenoids represent a diverse group of naturally occurring pigments found in various taxonomies, including plants, fungi and bacteria.1 In higher plants, carotenoids function as accessory pigments for photosynthesis and prevent photo-oxidative damage.2 Apocarotenoids, carotenoid cleavage products, include the plant hormones abscisic acid (ABA) and strigolactone.3,4 ABA plays an important role in regulating plant abiotic stress responses, differential growth and embryo dormancy; the recently discovered strigolactone inhibits shoot branching. For humans and animals, plant dietary carotenoids serve as precursors of vitamin A and other nutritional factors.5 In recent years, improvement of pro-vitamin A carotenoid content in seed endosperm of crop staples has been an important goal for alleviating global vitamin A deficiency.6,7 However, complexity and poorly understood pathway regulation are barriers to predictive metabolic engineering, especially in the Grass family (Poaceae) containing the major cereal crop staples (e.g., maize, sorghum, millets, rice, wheat, oats, barley, rye).

Predictable manipulation of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway reviewed in8 necessitates elucidation of biosynthetic step(s) that control carotenoid accumulation in various tissues. Previous studies suggested that control of flux to carotenoids is mediated by phytoene synthase (PSY), the first committed enzyme in the plastid-localized pathway.9–13 PSY catalyzes the condensation of two molecules of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate into 15-cis phytoene, the backbone of all C40 carotenoids and derived apocarotenoids. In Arabidopsis, tomato and other dicot plants, the nuclear-encoded PSY genes were shown to be upregulated during plastid development, leading to carotenoid accumulation in leaf, flower or fruit;14–16 transgenic overexpression of PSY causes elevated carotenoid content.6,17 However, additional studies are needed to facilitate predictable manipulation of this pathway in the many agronomically important food crops of the Poaceae. Therefore, we chose maize as a model system and the PSY gene as a key potential regulator of pathway flux to study carotenoid regulatory mechanisms in the Grasses. The maize B73 inbred line was the standard for study since carotenoids are found in both leaves and endosperm, and therefore comparisons of gene expression could be made among various carotenogenic tissues.

In Arabidopsis, a single PSY gene regulates 15-cis phytoene synthesis in all tissues. In contrast, most Grass species contain at least two PSY genes; PSY1 expression was shown to be strongly associated with endosperm carotenoid accumulation in maize and carotenoid absence in rice.10,13 More recent examination of the completed rice genome led to identification of a new PSY gene, PSY3, which was found to be present not only in rice, but also in maize and sorghum.18 All three genes were shown to encode functional enzymes in a heterologous bacterial platform.13,18 Quantitative transcript profiling for the three PSY genes revealed that the maize Y1 locus, PSY1, encoded the most abundant transcript in leaf and endosperm, carotenoid-accumulating tissues. In contrast, maize PSY3 transcripts were found predominately in root and embryo, carotenoid-limited tissues.19 The tissue-specific transcript patterns suggested that the maize PSY genes might be subfunctionlized and not merely redundant copies. We therefore tried to address the following questions: (1) What are internal and external cues that stimulate steady state mRNA levels of each maize PSY gene? (2) How do the three PSY genes contribute to controlling carotenogenesis for different physiological purposes? (3) Is PSY subfunctionalization unique to maize or is it a more general phenomenon seen in other Grasses? (4) What are the promoter cis-elements that may be responsible for the tissue-specific transcript patterns of the PSY genes?

Endosperm Carotenogenesis

In developing endosperm of the maize B73 inbred, or other genetically diverse inbreds carrying the Y1 allele, PSY1 was the only gene family member for which transcript levels significantly increased during endosperm development and correlated with accumulation of endosperm carotenoids;20 only low levels of PSY2 and PSY3 transcripts were detected in endosperm. The contribution of PSY2 and PSY3 to endosperm carotenoid accumulation was further evaluated in a line carrying the PSY1 allele, y1-602C. This allele carries a promoter mutation blocking PSY1 expression in endosperm but not in leaves. In y1-602C plants, the presence of PSY2 and PSY3 endosperm transcripts which can potentially encode functional proteins, could not compensate for the absence of endosperm PSY1. These data indicated that presence of functional PSY1 in endosperm is critical for carotenoid accumulation and the contribution of PSY2 and PSY3 was negligible. It could be that function of PSY2 and PSY3 proteins in endosperm plastids is prevented by an unknown mechanism that interferes with protein translation, protein stability or metabolon biogenesis, among other possibilities.

Leaf Carotenogenesis

The roles of maize PSY genes in leaf carotenogenesis were determined by monitoring transcript changes during de-etiolation. In dark-grown plants, PSY1 represented the major transcript. PSY2 was the only paralog for which transcript levels increased in response to illumination, suggesting that PSY2 plays an important role in controlling leaf carotenogenesis during greening. Moreover, the photoinduction of PSY2 by red or far-red light was repressed in the maize phytochrome deficit mutant elongated mesocotyl1 (elm1),21 indicating that phytochromes mediate PSY2 photoinduction by red and far-red light. In contrast, photoinduction of PSY2 was still observed in blue light illuminated elm1 seedlings, suggesting that another photoreceptor in addition to phytochrome, might be involved in blue light induction of PSY2.

Abiotic Stress: Thermotolerance

Although maize PSY1 was unresponsive to light during greening, we could not completely exclude a role in leaf carotenogenesis because of the high abundance of leaf PSY1 transcripts. Thus, we used a PSY1 frame-shift mutant, y1-8549, to investigate the effect on leaf carotenogenesis when PSY1 function was eliminated. At high temperature, y1-8549 mutant leaves were bleached due to photo-oxidative damage and chlorophyll and carotenoid levels decreased dramatically. These results suggested that functional maize PSY1 is essential for maintaining leaf carotenoid content, particularly under heat stress growth conditions. Therefore, maize PSY1 in a Y1 background, has an overlapping role in controlling both endosperm and leaf carotenogenesis.

Abiotic Stress: Drought and Salt

The abundance of PSY3 transcripts in roots suggested that PSY3 might have a unique role in root carotenogenesis, perhaps in the role of apocarotenoid formation. Moreover, searching of GenBank revealed a link between rice PSY3 expression and the ABA pathway or abiotic stresses, indicating that PSY3 in the Grasses may be involved in abiotic stress-induced carotenogenesis or in regulation of ABA biosynthesis. Maize seedlings were therefore subjected to various abiotic stresses to test this hypothesis. In roots, the levels of maize PSY3 mRNAs were induced by drought, salt and exogenous application of ABA.18 Moreover, the elevation in PSY3 transcripts was accompanied by induced levels of carotenoid intermediates, elevation of other downstream carotenogenic genes, and followed by ABA accumulation. The levels of PSY2 mRNAs were also affected by abiotic stress in leaves but PSY1 mRNAs were not elevated in any tissues tested. In particular we showed that root ABA accumulation is limited by PSY3 expression and de novo carotenogenesis in contrast to leaf ABA induction which is known to be regulated by carotenoid cleavage and not by carotenoid synthesis.22

The prevalence of rice PSY3 ESTs associated with abiotic stress was the rationale for us to investigate stress-induced regulation of maize PSY3. The upregulation of maize PSY3 transcript levels in response to abiotic stresses suggested that PSY3 responses were not unique to maize. Soon after we characterized the role of maize PSY3 in root carotenogenesis, the subfunctionlization of PSY paralogs in rice was also described by Welsh et al.23 Both rice PSY2 and PSY3 shared similar upregulation patterns with their maize orthologs; rice PSY2 was also photoinducible and root PSY3 mRNA levels increased during ABA formation in response to salt or drought stress. However, maize and rice PSY1 genes were different in their tissue specificity and in light responsive pattern; transcript levels of maize PSY1 showed endosperm developmental responses but lacked photoinduction, whereas the rice paralog showed the reverse, photoregulation without endosperm expression. We were intrigued that orthologs of only two of the three genes shared regulatory responses. We hypothesized that the progenitor allele, y1, found in many noncarotenogenic endosperm maize inbreds and the wild ancestor, teosinte, might actually possess photoregulation for PSY1; that domestication and cultivation may have led to selection of an allele exhibiting endosperm expression at the expense of light regulation.

Promoter Elements and Subfunctionalization

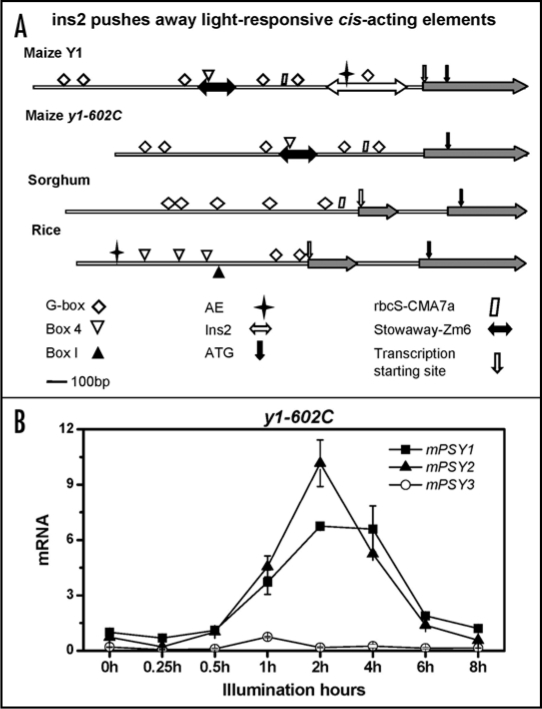

Examination of the PSY1 promoters in the grasses might give some clues as to the basis for the differential gene expression among the PSY1 alleles and across species. We hypothesized that the different expression pattern of maize PSY1 might be due to a change in regulatory components. Examination of maize and rice PSY1 promoter regions revealed that both genes shared a similar cis-acting element arrangement except for some transposon insertions in the maize PSY1 (Y1) promoter (Fig. 1A). The insertion of transposon ins2 at 300 bp up-stream of the maize PSY1 start codon has been shown to be statistically associated with endosperm carotenoid accumulation.10 We suspected this transposon insertion might have pushed away the cis-acting elements essential for PSY1 photoinduction. To verify this hypothesis, we tested for light regulation of PSY1 in the allele y1-602C which lacks the ins2 element. When y1-602C seedlings were illuminated, it was observed that the mRNA levels of both PSY1 and PSY2 increased while only PSY2 transcript levels were photoinduced in B73, which carries the Y1 allele (Fig. 1B). These results suggested that the maize y1-602C allele is more similar to rice PSY1 and the maize ancestor and that the ins2 insertion in the B73 Y1 allele is responsible for the loss of light regulation of maize PSY1 in Y1 backgrounds. In summary, maize plants that accumulate endosperm carotenoids, do not have the capacity for PSY1 photoregulation in green tissue, but must rely on PSY2 photoregulation alone.

Figure 1.

ins2 transposon in maize Y1 pushes away light-responsive cis-acting elements. (A) light-responsive cis-acting elements within maize Y1 and y1-602C allele, sorghum and rice PSY1 5′ upstream regions were predicted with PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html). Transposon ins2 inserts 300 bp upstream of transcript starting site in maize Y1 but not in allele y1-602C. (B) light-induced PSY1 and PSY2 expresssion during de-etiolation in y1-602C allele. Dark-grown nine-day-old dark-grown maize y1-602C seedlings were illuminated with white light (50 µmol m−2 s−1) for 0 to 8 h. The leaves of illuminated seedlings were harvested for cDNA preparation and used as templates for quantitative RT-PCR as carried out previously.20 All quantifications were first normalized to β-actin amplified using the same conditions and were made relative to PSY1 transcript levels in unilluminated seedlings. Values represent the mean of three RT-PCR replicates ±SD from five pooled plants.

Differential cis-acting elements in the PSY paralogs could also be responsible for the paralog-specific responses to various environmental cues. Besides the light responsive elements found in PSY1 and PSY2 promoters, an ABRE (ABA-responsive element) binding site was found in both rice and maize PSY3 promoter regions but not in either PSY1 or PSY223 and our unpublished data (Li F, Tsfadia O, Wurtzel ET).

In summary, the PSY gene triplication appears to be a general phenomenon in the Grasses. Subfunctionalization provides for fine control of carotenogenesis that serves numerous physiological purposes. Open questions remain regarding the unknown posttranscriptional mechanisms that control metabolon assembly and membrane association in various plastids found in different tissues.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants (to E.T.W.) from NIH (S06-GM08225, 1SC1GM081160-01 and 5SC1GM081160-02), PSC-CUNY, and NYS.

Abbreviations

- PSY

phytoene synthase

- ABA

abscisic acid

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/7798

References

- 1.Britton G, Liaaen-Jensen S, Pfander H, editors. Carotenoids Handbook. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niyogi KK. Safety valves for photosynthesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2000;3:455–460. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez-Roldan V, Fermas S, Brewer PB, Puech-Pages V, Dun EA, Pillot JP, et al. Strigolactone inhibition of shoot branching. Nature. 2008;455:189–194. doi: 10.1038/nature07271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umehara M, Hanada A, Yoshida S, Akiyama K, Arite T, Takeda-Kamiya N, et al. Inhibition of shoot branching by new terpenoid plant hormones. Nature. 2008;455:195–200. doi: 10.1038/nature07272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraser PD, Bramley PM. The biosynthesis and nutritional uses of carotenoids. Progr Lipid Res. 2004;43:228–265. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giuliano G, Tavazza R, Diretto G, Beyer P, Taylor MA. Metabolic engineering of carotenoid biosynthesis in plants. Trends Biotech. 2008;26:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harjes CE, Rocheford TR, Bai L, Brutnell TP, Kandianis CB, Sowinski SG, et al. Natural genetic variation in lycopene epsilon cyclase tapped for maize biofortification. Science. 2008;319:330–333. doi: 10.1126/science.1150255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matthews PD, Wurtzel ET. Biotechnology of food colorant production. In: Socaciu C, editor. Food Colorants: Chemical and Functional Properties. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Randolph LF, Hand DB. Relation between carotenoid content and number of genes per cell in diploid and tetraploid corn. J Agr Res. 1940;60:51–64. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palaisa KA, Morgante M, Williams M, Rafalski A. Contrasting effects of selection on sequence diversity and linkage disequilibrium at two phytoene synthase loci. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1795–1806. doi: 10.1105/tpc.012526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong JC, Lambert RJ, Wurtzel ET, Rocheford TR. QTL and candidate genes phytoene synthase and zetacarotene desaturase associated with the accumulation of carotenoids in maize. Theor Appl Genetics. 2004;108:349–359. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1436-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pozniak CJ, Knox RE, Clarke FR, Clarke JM. Identification of QTL and association of a phytoene synthase gene with endosperm colour in durum wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2007;114:525–537. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallagher CE, Matthews PD, Li F, Wurtzel ET. Gene duplication in the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway preceded evolution of the grasses (Poaceae) Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1776–1783. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.039818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartley GE, Scolnik PA. cDNA cloning, expression during development, and genome mapping of Psy2, a second tomato gene encoding phytoene synthase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25718–25721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Lintig J, Welsch R, Bonk M, Giuliano G, Batschauer A, Kleinig H. Light-dependent regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis occurs at the level of phytoene synthase expression and is mediated by phytochrome in Sinapis alba and Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Plant J. 1997;12:625–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giuliano G, Bartley GE, Scolnik PA. Regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis during tomato development. Plant Cell. 1993;5:379–387. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.4.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu C, Naqvi S, Breitenbach J, Sandmann G, Christou P, Capell T. Combinatorial genetic transformation generates a library of metabolic phenotypes for the carotenoid pathway in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18232–18237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809737105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li F, Vallabhaneni R, Wurtzel ET. PSY3, a new member of the phytoene synthase gene family conserved in the Poaceae and regulator of abiotic-stress-induced root carotenogenesis. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:1333–1345. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.111120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howitt CA, Pogson, Barry J. Carotenoid accumulation and function in seeds and non-green tissues. Plant, Cell Environm. 2006;29:435–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li F, Vallabhaneni R, Yu J, Rocheford T, Wurtzel ET. The maize phytoene synthase gene family: overlapping roles for carotenogenesis in endosperm, photomorphogenesis and thermal stress-tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:1334–1346. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.122119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sawers RJH, Linley PJ, Farmer PR, Hanley NP, Costich DE, Terry MJ, et al. elongated mesocotyl1, a phytochrome-deficient mutant of maize. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:155–163. doi: 10.1104/pp.006411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nambara E, Marion-Poll A. Abscisic acid biosynthesis and catabolism. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2005;56:165–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welsch R, Wust F, Bar C, Al-Babili S, Beyer P. A third phytoene synthase is devoted to abiotic stress-induced abscisic acid formation in rice and defines functional diversification of phytoene synthase genes. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:367–380. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.117028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]