Abstract

Lactoperoxidase (LPO) is a 78 kDa heme-containing oxidation–reduction enzyme present in milk, found in physiological fluids of mammals. LPO has an antimicrobial activity, and presumably contribute to the protective functions of milk against infectious diseases. In this study, recombinant vaccinia virus expressing bovine LPO (vv/bLPO) was constructed. In rabbit kidney (RK13) cells infected with vv/bLPO, recombinant bLPO was detected in both cell extracts and culture supernatants. Tunicamycin treatment decreased the molecular weight of recombinant bLPO, indicating that recombinant bLPO contains a N-linked glycosylation site. The replication of recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing bovine lactoferrin (vv/bLF) at a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 5 plaque-forming units (PFU)/cell was inhibited by antiviral activity of recombinant bLF, suggesting that vv/bLF has an antiviral effect against vaccinia virus. On the other hand, the replication of vv/bLPO at a moi of 5 PFU/cell was not inhibited by antiviral activity of recombinant bLPO, indicating that this recombinant virus could be used as a suitable viral vector. These results indicate that a combination of bLPO and vaccinia virus vector may be useful for medical and veterinary applications in vivo.

Keywords: Lactoperoxidase, Lactoferrin, N-linked glycosylation, Vaccinia virus, Antiviral effects

Introduction

Lactoperoxidase (LPO), a heme-containing oxidation–reduction enzyme present in milk and saliva, is part of an antimicrobial system, and converts thiocyanate (SCN−) to hypothiocyanate (OSCN−) in a hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-dependent reaction. The molecular weight of LPO is approximately 78 kDa, and the carbohydrate moiety comprises about 10% of the total weight (Mansson-Rahemtulla et al. 1988). Lactoperoxidase, myeloperoxidase (MPO), eosinophil peroxidase (EPO) and thyroid peroxidase (TPO) belong to the homologous mammalian peroxidase family and share 50–70% identity. Even higher homology can be found among their active site-related residues. These peroxidases can catalyze oxidation of halides and pseudohalides such as thiocyanate by hydrogen peroxide to form potent oxidant and bactericidal agents. Myeloperoxidase has been shown to inactivate influenza virus (Yamamoto et al. 1991) and HIV-1 virus (Klebanoff and Kazazi 1995). Human recombinant MPO has been shown to have a virucidal effect on HIV-1 virus (Moguilevsky et al. 1992; Chochola et al. 1994) and cytomegalovirus (El Messaoudi et al. 2002). However, few studies have examined whether LPO inhibits virus infection in vitro and in vivo.

Vaccinia virus belongs to the family of Poxviridae, and is the most intensively studied member of the poxvirus family (Moss 1990). Poxviruses replicate in the cytoplasm of infected cells without using nuclear enzymes of the host cells for transcription or DNA synthesis. Vaccinia virus has circumvented the need for nuclear enzymes by encoding or packaging a complete enzyme system for transcription (Moss 1990) and DNA synthesis, including a DNA-dependent DNA polymerase (Moss and Cooper 1982), DNA topoisomerase (Shuman and Moss 1987) and DNA ligase (Kerr and Smith 1989). Consequently, the vaccinia virus is widely used as an expression system in molecular biotechnology. Recombinant vaccinia virus has been demonstrated to be an effective antigen delivery system for infectious diseases in many species, with rabies and rinderpest being notable examples (Ertl and Xiang 1996; Tsukiyama et al. 1989). In addition recombinant vaccinia virus can give rise to long-term immunity (Inui et al. 1995). In previous studies, recombinant vaccinia virus has been also used to produce cytokines (e.g., interferon-β, interferon-γ; Kohonen-Corish et al. 1989; Nishikawa et al. 2000, 2001), but it has not yet been used for expression of antimicrobial milk proteins such as bovine LPO (bLPO). In the present study, we constructed recombinant vaccinia virus that expresses bLPO, and characterized production of bLPO, and replication of the recombinant virus. The expression and characterization of bLPO produced by recombinant vaccinia virus may be useful for the treatment of infectious diseases in humans or animals (Tanaka et al. 2006).

Materials and methods

Cells and viruses

Rabbit kidney (RK13) cells were cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM, Sigma Chemicals Co., St Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 8% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). Vaccinia virus LC16mO (mO) strain and its recombinant were propagated in RK13 cells in EMEM supplemented with 8% FBS.

Construction of recombinant vaccinia virus that expresses bLPO and bovine lactoferrin

The open reading frame of bLPO was amplified by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from bovine mammary gland cDNA using a pair of primers, 5′-ATAGACGGTATAAAAGGCCGG-3′ and 5′-CTGAGTCTACTTGAAATGGCATCG-3′. The length of the PCR products covered the full length of bLPO (2,295 bp). The sequence analysis was done using an Applied Biosystems sequencer (Foster City, CA, USA). bLF cDNA was amplified from mamary glands cells, using RT-PCR with primers designed from bLF cDNA (Tanaka et al. 2003a). The PCR products were blunted by T4 DNA polymerase and ligated with the vaccinia virus transfer vector pAK8 (Yasuda et al. 1990), which was cut with Sal I and then blunted. The plasmid (pAK/bLPO or pAK/bLF) was transfected into RK13 cells using a lipofectin reagent (Life Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) for 1 h after infection with the mO strain. After 2 days of incubation, culture medium was collected. We isolated recombinant virus (vv/bLPO or vv/bLF) produced by homologous recombination between pAK8 and mO strain in the viral thymidine kinase negative (TK−) cells in the presence of 100 μg/ml 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine, selecting TK− viruses by plaque isolation.

Immunofluorescence test

RK13 cells were infected with mO, vv/bLPO (5 plaque-forming units [PFU]/cell, 48 h), and subjected to IFAT. The infected RK13 cells were fixed with acetone, and incubated with mouse anti-bLPO monoclonal antibody (anti-bLPO mAb) or rabbit anti-bLPO polyclonal antibody (anti-bLPO Ab); these antibodies were produced by the present authors (Tanaka et al. 2003b; Watanabe et al. 1998). The cells were then stained with fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc., Birmingham, AL, USA) or fluorescein-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit antibody (Waco Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan). The cells were observed using fluorescence microscopy.

Sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and Western blot analysis

RK13 cells in tissue culture (colony diameter, 15 mm) were infected with the mO strain or the recombinant vaccinia virus at a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 5 PFU/cell for 1 h at 37 °C. Then, the cells were washed with EMEM and cultured in 500 μl of EMEM at 37 °C for 12–72 h. The cell extracts were prepared by sonication. The cell extracts and culture supernatants were subjected to SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions, followed by electro transfer of proteins to a PVDF membrane (Osmonics Inc., Westborough, MA, USA). The membrane was immersed in blocking buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] containing 3% bovine serum albumin) at 4 °C overnight, incubated with anti-bLPO Ab (diluted in the blocking buffer) at 37 °C for 1 h. The membrane was washed 3 times with PBS, and then incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Promega Co., Madison, WI, USA; diluted in the blocking buffer) at 37 °C for 1 h. The membrane was visualized by incubation with BCIP/NBT colour substrate (Promega Co.).

Tunicamycin treatment

Recombinant vaccinia virus-infected RK13 cells at a moi of 5 PFU/cell were incubated in EMEM containing 1 μg/ml tunicamycin (Sigma Chemicals Co.), which is a reagent that prevents synthesis of N-linked sugars, for 48 h post-infection (pi). The cells were then harvested, and the cell lysate was subjected to Western blot analysis to assay for expression of recombinant proteins.

Virus growth analysis

RK13 cells were infected with mO or recombinant viruses at a moi of 5 PFU/cell. After 1 h, the infected cells were washed with EMEM and cultured for 12–72 h after viral infection. Virus titers were determined by plaque titration according to Nishikawa et al. (2000). Data from this experiment were evaluated using Student’s t test. The 95% level of significance was used in the analysis.

Results

Expression of bLPO by recombinant vaccinia virus in RK13 cells

Vaccinia virus mO strain and pAK/bLPO were allowed to infect RK13 cells, and virus-containing medium of the infected RK13 cells was collected and analyzed by IFAT or Western blotting for the presence of recombinant bLPO. A recombinant bLPO-expressing clone was selected by the plaque-assay technique. vv/bLPO-infected cells were examined by IFAT and reacted with both anti-bLPO mAb (Fig. 1b) and anti-bLPO Ab (Fig. 1c). mO-infected cells served as negative reference and were labeled with both antibody reagents (Fig. 1a). The recombinant vaccinia virus, vv/bLPO coding for bLPO under the control of P7.5 promoter, was constructed by the homologous recombination method. To examine the expression of recombinant bLPO, RK13 cells were infected with mO or vv/bLPO at a moi of 5 PFU/cell. A recombinant bLPO band at 90 kDa was detected in cell extracts by Western blot analysis using anti-bLPO Ab after 48 h (Fig. 2a lane 4). Recombinant bLPO was also secreted into the supernatant, as indicated by recombinant bLPO bands at 88 and 90 kDa (Fig. 2b lane 4). The apparent molecular weight of these recombinant bLPO molecules (88 and 90 kDa) was greater than that of native bLPO (78 kDa). This result indicated that carbohydrate structure and amino acid sequence between recombinant bLPO and native bLPO were different. To test whether the increase of molecular weights in recombinant bLPO was due to glycosylation, the infected cells were treated with tunicamycin. As a result, no protein was secreted into the supernatant by infected cells treated with tunicamycin (Data not shown). In the cell extracts, the apparent molecular weight of bLPO was reduced to 80 kDa, indicating that recombinant bLPO were modified by N-linked sugars (Fig. 3 lane 4). The 90 kDa molecule would be a proprotein.

Fig. 1.

Immunofluorescence analysis of bLPO expressed in vv/bLPO-infected RK 13 cells. a mO-infected RK 13 cells labeled with anti-bLPO mAb and anti-bLPO Ab. b vv/bLPO-infected RK13 cells labeled with anti-bLPO mAb. c vv/bLPO-infected RK13 cells labeled with anti-bLPO Ab

Fig. 2.

Western blot analysis of bLPO expressed in vv/bLPO-infected RK13 cells. Cell extracts (a) and culture supernatants (b) of RK13 cells infected with vv/bLPO were analyzed using anti-bLPO Ab. Lane 1 RK13 cells; lane 2 mO-infected RK13 cells; lane 3 vv/green florescence protein-infected RK13 cells; lane 4 vv/bLPO-infected RK13 cells; lane 5 native bLPO (2 μg). Molecular masses of marker proteins are given in kDa

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of bLPO expressed by RK13 cells infected with vv/bLPO and treated with tunicamycin. Cell extracts of RK13 cells infected with vv/bLPO were analyzed using anti-bLPO Ab. Lane 1 mO-infected RK13 cells; lane 2 mO-infected RK13 cells treated with tunicamycin; lane 3 vv/bLPO-infected RK13 cells; lane 4 vv/bLPO-infected RK13 cells treated with tunicamycin; lane 5 native bLPO (2 μg). Molecular masses of marker proteins are given in kDa

Time course of bLPO production in the recombinant vaccinia virus system

To analyze the kinetics of expression of bLPO gene products, culture supernatants from RK13 cells infected with vv/bLPO were collected for 12–72 h pi. Recombinant bLPO were first detectable in culture supernatant at 24 h pi (Fig. 4 lane 2). The amount of recombinant bLPO increased 36–48 h pi, and reached plateau levels by 72 h pi (Fig. 4 lane 3–6).

Fig. 4.

Kinetics of recombinant bLPO synthesis. RK13 cells were infected with recombinant vaccinia virus and harvested at 12 (lane 1), 24 (lane 2), 36 (lane 3), 48 (lane 4), 60 (lane 5) and 72 h pi (lane 6). Lane 7 native bLPO (2 μg). Culture supernatants of infected RK13 cells were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-bLPO Ab. Molecular masses of marker proteins are given in kDa

Growth analysis of vv/bLPO in RK13 cells

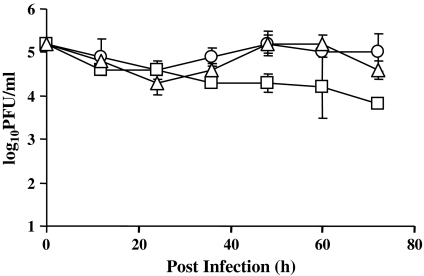

The growth curves of mO, vv/bLPO and recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing bovine lactoferrin (vv/bLF) are compared in Fig. 5. Peak titers (reached at 48 h pi) of mO, vv/bLPO and vv/bLF were 1.6 × 105, 1.6 × 105, and 0.2 × 105 plaque-forming units (PFU)/ml, respectively. These results indicate that bLF, but not bLPO, inhibits growth of recombinant virus in infected RK13 cells. There were no significant differences in growth between mO and vv/bLPO until 72 h pi (p > 0.05, Student’s t test mO vs. vv/bLPO). However, there were significant differences in growth between mO and vv/bLPO on one side and vv/bLF on the other side 48 h pi through 72 h pi (p < 0.05, Student’s t test mO or vv/bLPO vs. vv/bLF).

Fig. 5.

Virus growth analysis. RK13 cells were infected with mO (○), vv/bLPO (▵) and vv/bLF (□) at a moi of 5. Samples were harvested at the indicated time points, and progeny virus of RK13 cells was titrated in triplicate

Discussion

The expression systems using recombinant baculovirus or Chinese hamster ovary cells have been used to express bLPO (Tanaka et al. 2003b; Watanabe et al. 1998). However, there have been no previous reports of the use of vaccinia virus to express bLPO. The available evidence suggests that growth of vaccinia virus is inhibited by expression of bLPO. In the present study, recombinant vaccinia virus expressing bLPO (vv/bLPO) was constructed. RK13 cells were infected with vv/bLPO, and we characterized virus growth and post-translation modifications of the resultant product. Recombinant bLPO extracted from cell extracts and culture supernatants had an apparent molecular weight of 88 and 90 kDa, which is greater than that of native bLPO (78 kDa) in Western blot analysis. These size differences may be due to a difference in glycosylation level and differences in processing between RK13 cells and the mammary gland. When the infected RK13 cells were treated with tunicamycin, the apparent molecular weight of recombinant bLPO in the cells was 80 kDa, suggesting that recombinant bLPO is modified by N-linked glycosylation. Tunicamycin treatment completely abolished secretion of bLPO, indicating that N-linked glycosylation is essential for bLPO secretion. Therefore, recombinant bLPO was differentially processed during synthesis and secretion from RK13 cells compared with the mammary gland. A similar situation was previously reported for recombinant bLPO expressed in insect cells (Tanaka et al. 2003b). Interestingly, the molecular weight of recombinant bLPO produced in RK13 cells was higher than that expressed in insect cells. The carbohydrate structure analysis of purified recombinant bLPO expressed in insect cells and native bLPO found different reactivity with PHA-E4, PNA, and RCA120 by using lectin assay (Tanaka et al. 2003b). Therefore, the glycosylation level of recombinant protein might also be different between RK13 cells and insect cells. Most of the bLPO extracted from milk showed Asp-101 as the N-terminal amino acid residue (Dull et al. 1990; Watanabe et al. 2000). However, Watanabe et al. (2000) found also that different preparations of bLPO showed a different N-terminal amino acid residue. These variations may result from differences in the disk-electrophoresis and ion-exchange chromatography methods used for analysis (Carlström 1969). Thus, it might be possible that the 90 kDa form of recombinant bLPO did not undergo proteolysis, whereas the 88 kDa form of recombinant bLPO be the result of proteolysis of some N-terminal amino acid residues during synthesis and secretion by Rk 13 cells as observed for bLPO synthesized by the mammary gland.

Bovine Lactoferrin is a 80 kDa iron-binding glycoprotein found in physiological fluids of mammals. bLF has also an antimicrobial activity as bLPO, and presumably contributes to the protective functions of milk against infectious diseases. In RK13 cells infected with vv/bLF, recombinant bLF was detected in both cell extracts and culture supernatants (Data not shown). However, the replication of vv/bLF at a moi of 5 PFU/cell was inhibited by the antiviral activity of recombinant bLF, suggesting that vv/bLF has an antiviral effect against vaccinia virus. On the other hand, the expression of bLPO was also detected in cell extracts and culture supernatants of the vv/bLPO-infected cells as well as vv/bLF-infected cells. However, the replication of vv/bLPO at a moi of 5 PFU/cell was not inhibited by antiviral activity of recombinant bLPO, because LPO catalyzes oxidation of endogenous thiocyanate (SCN−) to produce hypothiocyanate (OSCN−) only in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). These products have a broad-spectrum antimicrobial and antiviral activity (Shin et al. 2001, 2005). Therefore due to the absence of thiocyanate (SCN−) and/or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) the replication of recombinant virus is not inhibited by recombinant bLPO.

Studies indicate that gene therapy using viral vectors containing the bLPO gene can produce anti microbial and anti-tumor activity (Odajima et al. 1996; Stanislawski et al. 1989). The major problem with such viral vectors is their attenuation. The recombinant vaccinia viruses in this report are TK− in phenotype that may reduce pathogenicity in vivo (Buller et al. 1985) because of insertion of the bLPO gene into the TK gene. Our results demonstrate the attenuation of the viral pathogenicity by introduction of the bLPO gene into vaccinia virus. Thus fine tuning of bLPO activity, may allow the control of virulence of vaccinia virus vector necessary for medical and veterinary applications in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Hokuto Foundation. The first author is supported by Postdoctoral Fellowships for Research Abroad of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

References

- Buller RML, Smith GL, Cremer K, Notkins AL, Moss B (1985) Decreased virulence of recombinant vaccinia virus expression vectors is associated with thymidine kinase-negative phenotype. Nature (London) 317:813–815 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Carlström A (1969) Lactoperoxidase. Identification of multiple molecular forms and their interrelationships. Acta Chem Scand 23:171–184 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chochola J, Yamaguchi Y, Moguilevsky N, Bollen A, Strosberg DA, Stanislawski M (1994) Virucidal effect of myeloperoxidase on human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infected cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 38:969–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dull TJ, Uyeda C, Strosberg AD, Nedwin G, Seilhamer JJ (1990) Molecular cloning of cDNA encoding bovine and human lactoperoxidase. DNA Cell Biol 9:499–509 [DOI] [PubMed]

- El Messaoudi K, Verheyden AM, Thiry L, Fourez S, Tasiaux N, Bollen A, Moguilevsky N (2002) Human recombinant myeloperoxidase antiviral activity on cytomegalovirus. J Med Virol 66:218–223 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ertl HC, Xiang Z (1996) Novel vaccine approaches. J Immunol 156:3579–3582 [PubMed]

- Inui K, Barrett T, Kitching RP, Yamanouchi K (1995) Long-term immunity in cattle vaccinated with a recombinant rinderpest vaccine. Vet Res 137:669–670 [PubMed]

- Kerr SM, Smith GL (1989) Vaccinia virus encodes a polypeptide with DNA ligase activity. Nucleic Acids Res 17:9039–9050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Klebanoff SJ, Kazazi F (1995) Inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by the amine oxidase-peroxidase system. J Clin Microbiol 33:2054–2057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kohonen-Corish MR, Blanden RV, King NJ (1989) Induction of cell surface expression of HLA antigens by human IFN-gamma encoded by recombinant vaccinia virus. J Immunol 143:623–627 [PubMed]

- Mansson-Rahemtulla B, Rahemtulla F, Baldone DC, Pruitt KM, Hjerpe A (1988) Purification and characterization of human salivary peroxidase. Biochemistry 27:233–239 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Moguilevsky N, Steens M, Thiriart C, Prieels JP, Thiry L, Bollen A (1992) Lethal oxidative damage to human immunodeficiency virus by human recombinant myeloperoxidase. FEBS Lett 302:209–212 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Moss B (1990) Regulation of vaccinia virus transcription. Annu Rev Biochem 59:661–688 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Moss B, Cooper N (1982) Genetic evidence for vaccinia virus-encoded DNA polymerase: isolation of phosphonoacetate-resistant enzyme from the cytoplasm of cells infected with mutant virus. J Virol 43:673–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa Y, Iwata A, Xuan X, Nagasawa H, Fujisaki K, Otsuka H, Mikami T (2000) Expression of canine interferon-β by a recombinant vaccinia virus. FEBS Lett 466:179–182 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa Y, Iwata A, Katsumata A, Xuan X, Nagasawa H, Igarashi I, Fujisaki K, Otsuka H, Mikami T (2001) Expression of canine interferon-γ by a recombinant vaccinia virus and its antiviral effect. Virus Res 75:113–121 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Odajima T, Onishi M, Hayama E, Motoji N, Momose Y, Shigematsu A (1996) Cytolysis of B-16 melanoma tumor cells mediated by the myeloperoxidase and lactoperoxidase systems. Biol Chem 377:689–693 [PubMed]

- Shin K, Hayasawa H, Lönnerdal B (2001) Inhibition of Escherichia coli respiratory enzymes by the lactoperoxidase-hydrogen peroxidase-thiocyanate antimicrobial system. J Appl Microbiol 90:489–493 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shin K, Wakabayashi H, Yamauchi K, Teraguchi S, Tamura Y, Kurokawa M, Shiraki K (2005) Effects of orally administered bovine lactoferrin and lactoperoxidase on influenza virus infection in mice. J Med Microbiol 54:717–723 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shuman S, Moss B (1987) Identification of a vaccinia virus gene encoding a type I DNA topoisomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84:7478–7482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stanislawski M, Rousseau V, Goavec M, Ito H (1989) Immunotoxins containing glucose oxidase and lactoperoxidase with tumoricidal properties: in vitro killing effectiveness in a mouse plasmacytoma cell model. Cancer Res 49:5497–5540 [PubMed]

- Tanaka T, Nakamura I, Lee NY, Kumura H, Shimazaki K (2003a) Expression of bovine lactoferrin and lactoferrin N-lobe by recombinant baculovirus and its antimicrobial activity against Prototheca zopfii. Biochem Cell Biol 81:349–354 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tanaka T, Sato S, Kumura H, Shimazaki K (2003b) Expression and characterization of bovine lactoperoxidase by recombinant baculovirus. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 67:2254–2261 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tanaka T, Murakami S, Kumura H, Igarashi I, Shimazaki K (2006) Parasiticidal activity of bovine lactoperoxidase against Toxoplasma gondii. Biochem Cell Biol 84:774–779 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tsukiyama K, Yoshikawa Y, Kamata H, Imaoka K, Asano K, Funahashi S, Maruyama T, Shida H, Sugimoto M, Yamanouchi K (1989) Development of heat-stable recombinant rinderpest vaccine. Arch Virol 107:225–235 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Watanabe S, Varsalona F, Yoo YC, Guillaume JP, Bollen A, Shimazaki K, Moguilevsky N (1998) Recombinant bovine lactoperoxidase as a tool to study the heme environment in mammalian peroxidases. FEBS Lett 441:476–479 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Watanabe S, Murata S, Kumura H, Nakamura S, Bollen A, Moguilevsky N, Shimazaki K (2000) Bovine lactoperoxidase and its recombinant: comparison of structure and some biochemical properties. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 274:756–761 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto K, Miyoshi-Koshio T, Utsuki Y, Mizuno S, Suzuki K (1991) Virucidal activity and viral protein modification by myeloperoxidase: a candidate for defense factor of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes against influenza virus infection. J Infect Dis 164:8–14 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yasuda A, Kimura-Kuroda J, Ogimoto M, Miyamoto M, Sata T, Sato T, Takamura C, Kurata T, Kojima A, Yasui K (1990) Induction of protective immunity in animals vaccinated with recombinant vaccinia viruses that express PreM and E glycoproteins of Japanese encephalitis virus. J Virol 64:2788–2795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]