Abstract

Insulin degrading enzyme (IDE) utilizes a large catalytic chamber to selectively bind and degrade peptide substrates such as insulin and amyloid β (Aβ). Tight interactions with substrates occur at an exosite located ~30Å away from the catalytic center that anchors the N-terminus of substrates to facilitate binding and subsequent cleavages at the catalytic site. However, IDE also degrades peptide substrates that are too short to occupy both the catalytic site and the exosite simultaneously. Here, we use kinins as a model system to address the kinetics and regulation of human IDE with short peptides. IDE specifically degrades bradykinin and kallidin at the Pro/Phe site. A 1.9Å crystal structure of bradykinin-bound IDE reveals the binding of bradykinin to the exosite, and not to the catalytic site. In agreement with observed high Km values, this suggests low affinity of bradykinin for IDE. This structure also provides the molecular basis on how the binding of short peptides at the exosite could regulate substrate recognition. We also found that human IDE is potently inhibited by physiologically relevant concentrations of S-nitrosylation and oxidation agents. Cysteine-directed modifications play a key role, since an IDE mutant devoid of all thirteen cysteines is insensitive to the inhibition by S-nitroso-glutathione, hydrogen peroxide, or N-ethylmaleimide. Specifically, cysteine 819 of human IDE is located inside the catalytic chamber pointing towards an extended hydrophobic pocket and is critical for the inactivation. Thiol-directed modification of this residue likely causes local structural perturbation to reduce substrate binding and catalysis.

INTRODUCTION

Insulin degrading enzyme (IDE) is an evolutionarily conserved zinc metalloprotease (M16 family) that is involved in the clearance of various physiologically relevant peptide substrates (1–4). In addition to its ability to degrade insulin (5) and amyloid β (Aβ) (3, 6, 7), IDE can hydrolyze a broad variety of biologically active peptides, which vary both by sequence and length. Insulin-like growth factor-2 (IGF-2) (1, 8), atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) (9), transforming growth factor α (TGF-α) (10), and glucagon (11) are a few examples. The crystal structures of human IDE (4, 12, 13) have provided the first molecular details, which elucidate the mechanisms of substrate recognition. IDE is organized in two 56-kDa catalytic N- and C-terminal domains that comprise four structurally homologous αβ roll domains. The two functional N- and C-terminal domains, joined by an extended 28 amino acid residues loop, enclose a large catalytic chamber that can fit peptides smaller than 70-amino acids long. Size and charge distribution of this catalytic chamber are properties likely involved in the regulation of recognition and binding of substrates. The preference of IDE for substrates with basic and hydrophobic amino acids at the P1-P1′ sites arise from both the hydrophobic and electrostatic nature of the catalytic chamber near the catalytic residues. IDE also undergoes a conformational switch from a closed to an open state to allow entrance of the substrates in its catalytic chamber. Once entrapped, the substrates undergo conformational changes in order to interact with two discrete regions of IDE for their degradation.

Thus far, the only crystal structures of IDE-substrate complexes that were solved, involved molecules that were at least 30aa in length (13). In these structures, substrates are bound in the catalytic chamber by establishing contacts with regions of IDE that extend from the catalytic site located in domain 1, and made of the typical HxxEH motif (14), to the exosite made of conserved residues and located ~30Å distant from the catalytic Zn2+ (12). IDE accommodates its substrates in the catalytic chamber by anchoring their N-terminal end to the exosite, allowing the positioning of cleavable regions in proximity to the catalytic center (4). However, this type of interaction cannot apply to the recognition of substrates less than 12 amino acids long, such as the nonapeptide hormone bradykinin (15, 16) or the pentapeptide enkephalin because such short peptide substrates cannot bind both the exosite and the catalytic site simultaneously. The degradation of short peptide substrates by IDE has interesting features, such as the observations that ATP and several small substrates can activate IDE (16, 17). Furthermore, IDE has substantially higher rate of catalysis towards short substrates (>2,000 sec−1) rather than large substrates like insulin (0.5 min−1) (18, 19). We recently showed that ATP can facilitate the conformational switch of IDE, which in turn may contribute to the catalytic activity of IDE (12). However, the molecular details of how IDE recognizes short peptide substrates and how they facilitate catalysis remain elusive.

Bradykinin is a vasoactive peptide of the family of kinins. In response to inflammatory events such as tissue damage, allergic reactions, and viral infections, kinins are generated from the cleavage of the precursor kininogens by enzymes known as kallikreins, and serve as potent mediators of pain, inflammation, and vasodilatation (20, 21). G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) known to mediate kinin function are of two types: the B1 receptor, which is induced during inflammation, and the B2 receptor, constitutively expressed in many cell types (22, 23). The affinity of the interaction between kinins and their receptors can be altered upon the cleavage of kinins (24), and in addition to kallikreins, kinins are also shown to be hydrolyzed by the metalloproteases angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) (25), neprilysin (NEP) (26), endothelin-converting enzyme-1 (ECE-1) (27, 28), IDE (15, 16), and EP24.15 (29).

The degradation of kinins by IDE is not well studied. For example, the cleavage site of kinins by IDE, the detailed kinetic analysis, as well as the structural basis for the recognition of bradykinin by IDE remain to be elucidated. Furthermore, the physiological relevance for the degradation of kinins by IDE remains elusive. IDE localized on the cell surface and in the extracellular milieu can potentially control kinin-mediated signaling and receptor recycling by regulating the extracellular level of kinins. In addition, endosomal IDE could be involved in the degradation of kinins released from endocytosed B2 receptor (30).

Growing evidence correlates the reactions of cysteines with the regulation of protein function. An interesting feature of human IDE is the presence of 13 cysteines in its primary structure that are not immediately involved in catalysis. While IDE has been shown to be post-translationally modified and regulated, no direct role of the cysteines has been established (31–34). The modifications of IDE that have been identified include inhibition studies by alkylation and oxidation. Oxidative damage of IDE, and the consequent impairment of its Aβ-degrading activity may in part explain the deposition of Aβ in the brain of Alzheimer disease’s (AD) patients in the presence of oxidative stress conditions (35). Recently, the nitrosylation of proteins, such as NMDA receptors, caspase-3, parkin, protein disulfide isomerase and matrix metalloprotease-9, has been shown to play key roles in the modulation of protein function (31, 36, 37). Furthermore, crucial cysteine residues and the molecular basis for this emerging post-translation modification were elucidated (31, 37). Several lines of evidence have correlated the exaggerated production of NO with pathological responses, such as insulin resistance and the formation of amyloid-β plaques (38–41). However, questions whether the modulation of the function of IDE, involved in both the degradation of insulin and Aβ, can occur by nitrosylation have not been addressed.

In order to elucidate the structural bases of the recognition and cleavage of short peptide substrates by IDE, we generated an IDE mutant completely free of cysteines by sequence conservation and local environment analyses of the 13 cysteine residues of human IDE. This mutant resulted in an active enzyme and in diffracting-quality crystals that had the advantage of growing in non-reducing conditions. We therefore used two kinins, bradykinin and kallidin (Lys-bradykinin) as a model system of short peptides, and report here mass spectrometry, kinetic and X-ray crystallographic data showing that kinins are low-affinity substrates of IDE. Subsequently, because of the need of an IDE cysteine-free mutant in order to obtain diffracting-quality crystals, we have also undertaken the investigation of the role of cysteines in IDE as potential target for post-translational modifications. We have therefore examined the effect in vitro on IDE activity of several thiol-directed modifications using specific aminoacidic substitutions. We identify a key cysteine residue that by perturbing the local structural environment of IDE’s catalytic chamber plays a crucial role in the functional impairment of the enzymatic activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of IDE mutants

Protocols for construction of the expression vector for human IDE were previously reported (13). Using as a template the plasmid pProEx-IDE, the Invitrogen Multi-QuickChange kit was used to introduce multiple mutations of all 13 cysteine residues of IDE in two separate constructs: pProEx-IDE-CF-123 mutant free of cysteines in domains 1, 2, and 3 only (containing the substitutions C110L, C171S, C178A, C257V, C414L, C573N, C590S); and pProEx-IDE-CF-4 mutant free of cysteines in domain 4 only (containing the substitutions C789S, C812A, C819A, C904S, C966N, C974A) (Table 1 and Figure S1, Supporting Information). In the process of making IDE-CF-4, five mutants (M1-M5) containing combinations of mutated cysteines located in domain 4 only (M1: C904S/C966N, M2: C789S/C904S/C966N, M3: C812A/C819A/C904S/C966N, M4: C789S/C904S/C966N/C974A, M5: C789S/C819A/C904S/C966N, respectively) were created as well. The choice of residues to use in replacing cysteines was based on the evolutionary conserved analysis of IDE sequences from vertebrate, plant, fungi and yeast, with the aim of not perturbing the local environment and therefore the structural integrity (Figure S2, Supporting Information). The mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The catalytic activities of the purified proteins of these two IDE mutants were shown to be comparable with wild-type IDE. We then generated a full-length mutant (IDE-CF) completely free of cysteines by swapping the DNA encoding IDE-CF-4 into the vector pProEx-IDE-CF-123. IDE-CF contains the following substitutions: C110L, C171S, C178A, C257V, C414L, C573N, C590S, C789S, C812A, C819A, C904S, C966N, and C974A. Using the Invitrogen Quick-change kit we also generated the single point mutant IDE-C819A, using pProEx-IDE as the template, and 6 single point mutants (IDE-CF-S789C, IDE-CF-A812C, IDE-CF-A819C, IDE-CF-S904C, IDE-CF-N966C, IDE-CF-A974C) with cysteine residues inserted back on a CF background using pProEx-IDE-CF as the template. A complete list of the mutants generated and used in this study is reported in Table 1. For the crystallization of the complex with bradykinin, the mutation E111Q was introduced into the pProEx-IDE-CF expression vector.

Table 1.

IDE cysteine mutants

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 110 | 171 | 178 | 257 | 414 | 573 | 590 | 789 | 812 | 819 | 904 | 966 | 974 | |

| CF | L | S | A | V | L | N | S | S | A | A | S | N | A |

| CF-123 | L | S | A | V | L | N | S | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CF-4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | S | A | A | S | N | A |

| M1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | S | N | - |

| M2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | S | - | - | S | N | - |

| M3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | A | A | S | N | - |

| M4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | S | - | - | S | N | A |

| M5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | S | A | - | S | N | - |

| C819A | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | A | - | - | - |

| CF-S789A | L | S | A | V | L | N | S | C | A | A | S | N | A |

| CF-A812C | L | S | A | V | L | N | S | S | C | A | S | N | A |

| CF-A819C | L | S | A | V | L | N | S | S | A | C | S | N | A |

| CF-S904C | L | S | A | V | L | N | S | S | A | A | C | N | A |

| CF-N966C | L | S | A | V | L | N | S | S | A | A | S | C | A |

| CF-A974C | L | S | A | V | L | N | S | S | A | A | S | N | C |

Expression and purification of recombinant IDE

Recombinant IDE proteins were expressed and fully purified as previously reported (12). However, a small-scale protocol for expression and partial purification of IDE samples was used to perform initial NEM sensitivity characterization of IDE mutants. E. coli Rosetta (DE3) cells containing the various IDE plasmids were sonicated after resuspension in lysis buffer, composed of 20 mM Tris, pH 7.7, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM PMSF, 0.1 mg/ml lysozyme. The soluble protein fraction (crude cell lysate) was separated from the cell debris by centrifugation at 35,000 rpm and was loaded on a Ni–NTA column, which had been previously equilibrated with 20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM PMSF. Then, the Ni–NTA column was washed with the equilibration buffer, followed by a second wash with the same buffer containing 5 mM imidazole to remove any loosely bound protein. The histidine-tagged human enzyme was eluted from the column by a step gradient of 150 mM imidazole. The fractions with the partially pure IDE were pooled and concentrated using Amicon 30 (MWCO 30,000) and centricon-10 and stored at −80 °C.

Enzymatic assays of kinins degradation by IDE

Bradykinin and kallidin were purchased from AnaSpec, substrate V was purchased from R&D Systems. Proteolysis of bradykinin and kallidin by IDE-CF was monitored by using the fluorogenic peptide substrate V (7-methoxycoumarin-4-yl-acetyl-NPPGFSAFK-2,4-dinitrophenyl) (42); 90 μl of 0.5 μM substrate V were dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.3, and mixed with 10 μl of various concentrations (0–14 mM) of bradykinin and kallidin in two separate experiments. Immediately before measuring fluorescence signal from the cleavage of substrate V, 5 μl of 0.2 mg/ml IDE-CF was added to the reaction mixture and the assay was conducted at 37 °C for 15 min. The hydrolysis of substrate V was measured using a Tecan Safire2 microplate reader (Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland) with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 327 nm and 395 nm, respectively.

Mass Spectrometry analysis of kinins degradation by IDE

MALDI-TOF and MS-MS spectrometry characterization of the proteolytic fragments generated by the cleavage by IDE-CF of bradykinin and kallidin, were performed using a Voyager 4700 MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems). Protein samples were incubated for 30 min in 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.3, with bradykinin and kallidin in two separate experiments. Reaction mixtures were quenched by adding 0.5 mM EDTA at time points 0 and 30 min; 5 μl of the quenched reaction mixtures were mixed with an equal volume of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and purified through a C-18 ZipTip (Millipore); 1 μl of the purified samples were then mixed with matrix alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA, Sigma) and spotted on a metal plate (ABI). Analysis of the peaks (m/z) in relation with the amino acid sequence of bradykinin and kallidin was performed by FindPept tool from the ExPASy proteomic webserver. MS-MS analysis was performed by fragmentation of the highest peaks (precursor masses) from a MALDI-TOF run. The consequent examination of the fragmentation obtained was performed by de novo analysis using the software Data Explorer from ABI.

Crystallization, data collection and structure determination

The catalytically inactive mutant IDE-CF-E111Q was used for crystallization trials in order to avoid cleavage of bradykinin. The purified enzyme (0.1 mM) was pre-incubated with bradykinin using molar ratios of 1:10 and 1:100 for 1 hour before crystallization, or before going through each of four consecutive gel-filtrations in superdex-200 column as previously reported (13). Crystals were obtained in 7–10 days at 18 °C, by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method by mixing 1 μl of protein-substrate solution with an equal volume of precipitant solution as previously reported (12). Crystals were cryo-protected in two successive steps, using a concentrated solution of precipitant containing 15% and 30% glycerol, and flash cryo-cooled in liquid N2. Diffraction data were collected at the beamline 19-ID at the Structural Biology Center at Argonne National Laboratory. HKL2000 (43) and the CCP4 suite of programs (44) were used for integration reduction and scaling of X-ray diffraction data. The structure of the complex IDE-bradykinin (IDE•BK) was solved by molecular replacement with the program PHASER (45). In order to avoid model-bias, coordinates from substrate-free IDE (PDB ID 2jg4) (12) were used as starting model for phasing using molecular replacement. Structure refinement was performed by PHENIX (46), and manual model rebuilding by Coot (47). The structure was validated by PROCHECK (48). Data collection, processing and refinement statistics are reported in Table 2. All graphics were generated using PyMOL (49).

Table 2.

Crystallographic statistics

| Data Collection | |

|---|---|

| Beamline | APS 19-ID |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.03320 |

| Space group | P65 |

| Cell dimension (Å) | |

| a | 262.5 |

| b | 262.5 |

| c | 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 30–1.9 |

| Rsym (%)a | 8.8 (51.2) |

| I/σ | 15.7 (1.75) |

| Redundancyb | 2.4 (2.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.4 (91.7) |

| Unique reflections | 595933 (248865) |

|

Refinement | |

| Rworkc(%) | 18.3 (25.5) |

| Rfree d(%) | 20.8 (29.8) |

| B factor (Å2) | |

| Protein | 30.6 |

| N-terminal Bradykinin | 46.3 |

| Water | 40.0 |

| Rmsdf | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.01 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.14 |

| Ramachandran plot (%)g | |

| Favorable region | 92.6 |

| Allowed region | 7.4 |

| Generously allowed region | 0 |

| Disallowed region | 0 |

| PDB accession code | 3CWW |

Values in parentheses indicate the highest resolution shell

Rsym = Σ (I − 〈 I 〉)/Σ 〈 I 〉

Nobs/Nunique

Rwork = Σhkl||Fobs| − k |Fcalc||/Σhkl|Fobs|

Rfree, is the Rwork value for 5% of the reflections excluded from the refinement (61)

rms deviations (rmsd) calculated with PHENIX (46)

Values are from PROCHECK (48)

The sensitivity of IDE to the treatment with NEM, GSNO, and H2O2

N-ethyl-maleimide (22), S-nitroso-glutathione (GSNO), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) were purchased from Sigma. Fluorescein-Aβ-(1–40)-Lys-biotin (FAβB) was a gift from Dr. Leissring. Initial characterization of IDE sensitivity to NEM was performed by incubation of 1 mg/ml of purified IDE (wild-type or mutant) in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, at 25 °C for 1 hour, containing various concentrations of NEM (0.2–1 mM), H2O2 (0.025–2.5 mM), or GSNO (0.03–1mM). In every case, aliquots of the reaction mixture were removed after 1 hour and assayed for enzymatic activity using either 0.5 μM fluorogenic substrate V (42) or 1.5 μM fluorogenic amyloid-β (FAβB) (50) as substrates. Fluorescence measurements were taken using a Tecan Safire2 microplate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths set respectively at 327 nm and 395 nm for substrate V and 488 nm and 525 nm for FAβB. Relative activities are reported assuming that 100% is the control reaction in which the enzymes were incubated only with buffer.

RESULTS

Characterization of the degradation of short peptide substrates kinins by IDE

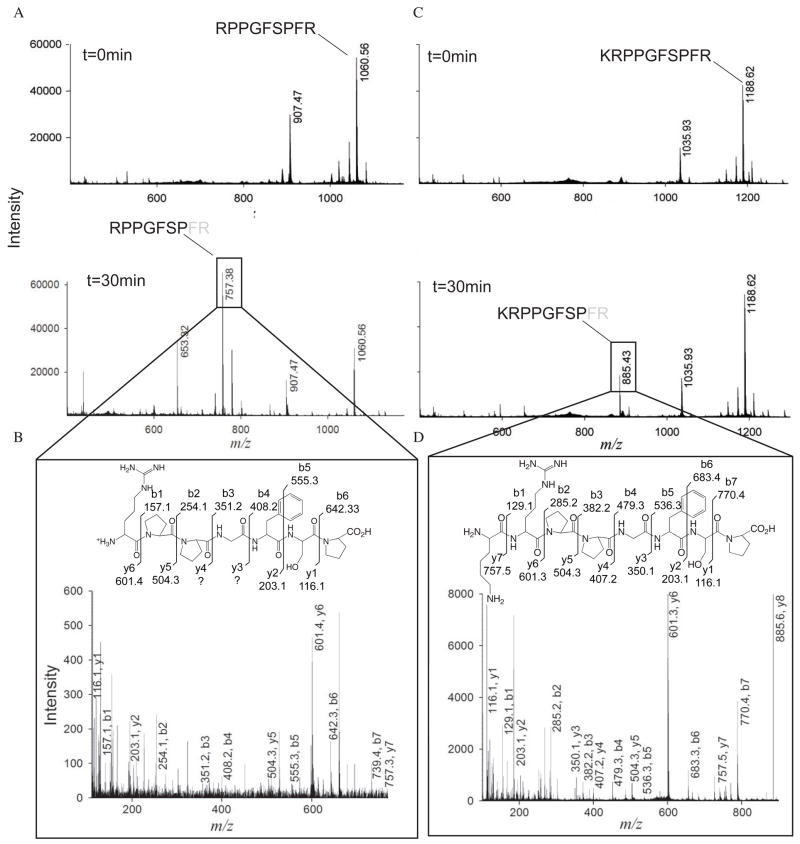

To address the possible role of IDE in the catabolism of kinins, we incubated bradykinin or kallidin (Lys-bradykinin) with purified recombinant human IDE. We found that bradykinin is hydrolyzed after 30-minute incubation, as shown by mass spectrometry analysis using MALDI-TOF (Figure 1A). The cleavage site is located between residues Pro7 and Phe8 (peak at m/z 757.38), with release of the C-terminal di-peptide Phe8-Arg9. Same cleavage of the C-terminal di-peptide of bradykinin is observed by ACE and NEP (51). To confirm the position of the cleavage site we used MS-MS to determine the exact sequence of the peaks detected by MALDI-TOF. The MS-MS fragmentation spectra on the major peaks observed allowed confirming the sequences of the cleaved peptide. De novo sequencing confirmed that the ion at m/z=757.38 was the fragment Arg1-Pro7 of bradykinin, based on the fact that most of b and y ions could be identified (Figure 1B). An additional minor cleavage site for bradykinin was revealed in the peak at m/z=653.32 (Figure 1A), which may correspond to the fragment Phe5-Arg9 of bradykinin after cleavage between residues Gly4 and Phe5. However, no MS-MS data could be obtained to confirm this hypothesis.

Figure 1.

Mass spectrometry analysis of bradykinin and kallidin degradation by IDE-CF. (A) MALDI-TOF spectra of bradykinin degradation at 0 min (top) and 30 min (bottom). The amino acidic sequence of bradykinin is shown for the peaks corresponding to the mass of full-length bradykinin (top) and for the cleavage product (bottom). (B) MS-MS spectra of precursor mass 757.38 for bradykinin as detected by MALDI-TOF. De novo prediction of the peptide sequence is labeled on the corresponding y and b ions on the peaks from the spectra and on the chemical structure of bradykinin. (C) and (D) Same as panels A and B for kallidin.

We then tested whether kallidin can be digested by IDE. Incubation for 30 min resulted in the production of a major peak at m/z=885.43, which corresponds to the fragment Lys1-Pro8 after cleavage between Pro8 and Phe9 (Figure 1C). MS-MS analysis confirmed the identity of this fragment peptide with all residues of kallidin cleavage product identified (Figure 1D). Together, our data show that IDE cleaves both bradykinin and kallidin at the same site, which is between Pro and Phe.

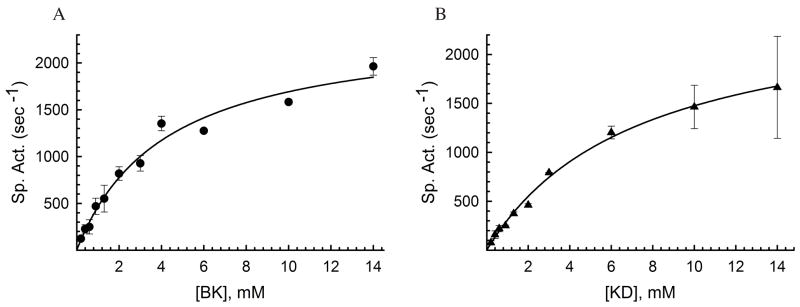

We then performed kinetic analysis to determine the affinity of IDE for kinins. We used substrate V as a fluorescent probe to monitor the proteolytic reaction (42). Substrate V has an internally quenched fluorescent peptide derived from the amino acid sequence of bradykinin. The reaction was performed with excess (~15mM) of bradykinin or kallidin with respect to substrate V (0.5μM) to ensure that the kinetic reaction represented a good approximation of the catabolism of bradykinin or kallidin. We observed Km values for the degradation of bradykinin and kallidin by IDE of 4.2±0.6 mM, and 7.3±0.7 mM, respectively. This suggests that IDE only has a weak affinity for kinins (Figure 2). However, the kcat for bradykinin and kallidin is around 2,000 sec−1, consistent with the notion that IDE can rapidly, but not necessarily more efficiently, degrade small peptide substrates (19).

Figure 2.

Kinetic analysis of bradykinin and kallidin degradation by IDE. Specific activities (sec−1) of IDE-CF using the indicated bradykinin (A) and kallidin (B) concentrations and 0.5 μM substrate V are shown. The activity was measured at 37 °C for 5 min. Km values were determined to be 4.2±0.6 mM, and 7.3±0.7 mM for bradykinin and kallidin, respectively. Data utilized for fitting kinetic curves are mean ± SD representative of two independent assays performed in duplicates.

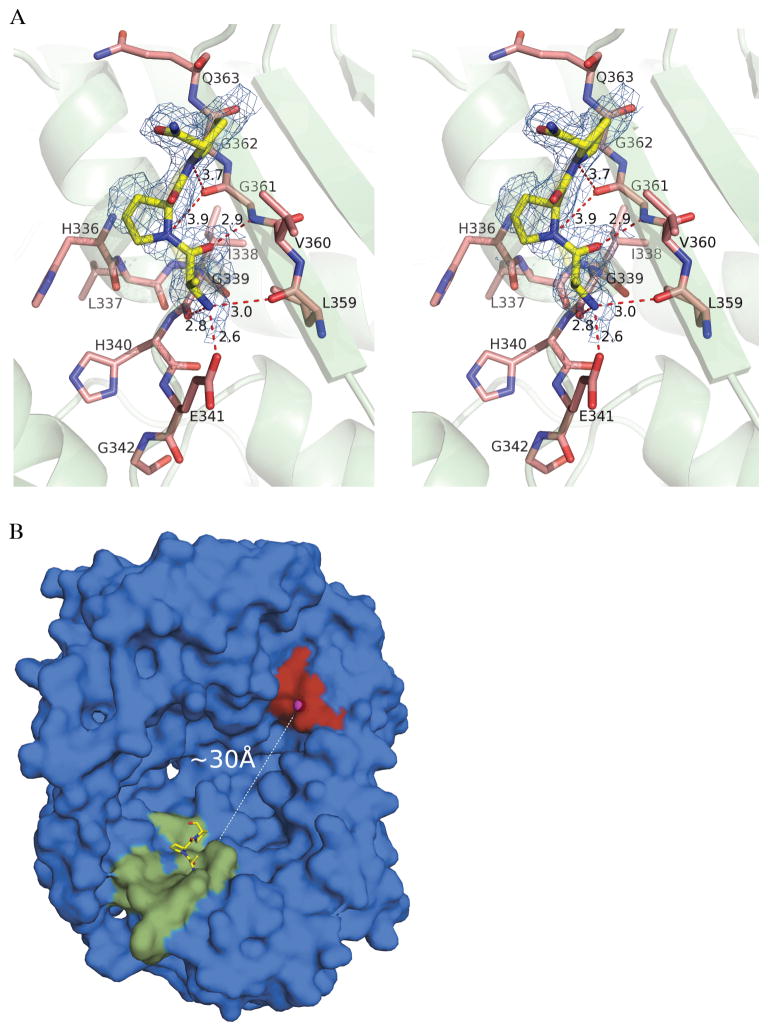

Crystal structure of IDE in complex with bradykinin

Our structural analysis of IDE in complex with peptide substrates that are greater than 30 amino acid long reveals that the anchoring of peptide substrates into the exosite of IDE plays a key role in substrate recognition (4). However, bradykinin or kallidin are too short to anchor to both exosite and catalytic site of IDE for their cleavage. To elucidate the structural basis for the binding of bradykinin into the catalytic chamber of IDE and to understand how IDE selects and binds small molecules, we solved the structure of the complex IDE-bradykinin (IDE•BK).

The recombinant human IDE used in our previous structural analysis of IDE-substrate complexes has a glutamate to glutamine mutation at residue 111 for the catalytic inactivation. In order to obtain crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction experiments, this protein sample needed to be purified in the presence of reducing agents β-mercapto-ethanol, DTT or TCEP. However, under these conditions we failed to generate diffracting bradykinin-bound IDE crystals. We hypothesized that the necessity of reducing agents during purification and crystallization is due to the oxidative modification(s) of the 13 cysteine residues present in human IDE. These 13 cysteines are not evolutionarily conserved among IDE from various organisms (Figure S2, Supporting Information). While 12 out of the 13 cysteines are conserved in mammals, none of them are present either in high plants (IDE homologs from Arabidopsis thaliana, tomato, and rice) or in pitrilysin (an IDE homolog from E. coli). C110 is located in the catalytic center and is the most conserved cysteine. However, the side chain of C110 is pointing in the opposite direction from the catalytic site, and was previously shown to be not involved in substrate binding and catalysis (12, 13). Mutations of C110 to either glycine or serine have no effect on the enzymatic activity of IDE (34). The next most conserved cysteines are C257 and C819, located in domain 1 and 4, respectively. Together with the analysis of the local environment, sequence conservation suggested that mutating all cysteines in human IDE would not affect the catalytic activity. We thus constructed an IDE mutant (IDE-CF) that had all thirteen cysteines mutated to the appropriate residues chosen by analysis of local environments of the structure of human IDE as well as by analysis of sequence conservation (Table 1 and Figure S1, Supporting Information). Indeed, IDE-CF had specific activity similar to wild-type using the bradykinin-mimetic substrate V as the substrate (specific activities of 3.0±0.4 min−1 and 4.5±0.1 min−1 for IDE-WT and IDE-CF, respectively when 0.5 μM fluorogenic substrate V was used).

After introducing the catalytically inactivating mutation E111Q, we found that IDE-CF-E111Q was particularly successful in forming ordered crystals of considerable size at a more rapid rate than the original construct (IDE-E111Q). We therefore utilized this IDE mutant for the structural characterization of bradykinin-bound IDE (IDE•BK). We initially performed co-crystallization experiments with bradykinin, but inspection of electron density maps did not reveal the presence of a bound substrate in the catalytic chamber of IDE. Crystals of the IDE•BK complex were finally obtained after several cycles of incubation of catalytically inactive IDE mutant with up to 10 mM bradykinin to maximize the formation of IDE•BK complex without noticeable precipitation. These crystals diffracted up to 1.9Å (Table 2). The overall fold of this complex is in the closed conformation and virtually identical to the previous structures of substrate-bound IDE-E111Q (rms deviation of 0.3 Å for all Cα atoms) (13), consistent with the notion that our cysteine mutations did not alter the IDE structure.

The electron density map calculated at 1.9Å showed peaks in the catalytic chamber in proximity to the exosite. The shape of this density could be modeled well with the N-terminal three residues of bradykinin (Arg1-Pro2-Pro3) (Figure 3A) with occupancy of ~80%. The side chain of the N-terminal arginine is not visible, in part because it points towards the catalytic chamber and does not make specific interactions with surrounding residues. Thus, it is modeled as Ala1 in our structure. Residues 336–342 and 359–363 of IDE are involved in interactions with bradykinin. Residues 336–342 constitute the exosite, and are highly conserved among different species (Figure S1, Supporting Information). They belong to a helix-loop segment located laterally to a 7-stranded β-sheet that makes more extensive polar interactions with bradykinin (Figure 3A). The oxygen atoms of the side chain of Glu341 and of the backbone carbonyl of Gly339 are within H-bonds distances from the backbone amide of the terminal Arg1 of bradykinin. Also, residues 359 and 361 make polar interactions with the N-terminal bradykinin. Hydrogen bonds are mediated by the main-chain carbonyl oxygen atom of Leu359 and the amido group of Gly361 with the backbone N and C atoms of Arg1 and Pro2 of bradykinin, respectively. The carbonyl of Gly361 is also favorably directed to make polar interactions with main-chain atoms of Pro2 and Pro3 of bradykinin. Residues 359–363 are located on the lateral (external) β-strand of the extended 7-stranded β-sheet.

Figure 3.

Structural analysis of bradykinin-bound IDE. (A) Stereo view of the interactions between bradykinin and the exosite of IDE. The N-terminal residues Arg(Ala)1-Pro2-Pro3 of bradykinin are shown as yellow sticks. Protein residues belonging to the exosite are shown as salmon sticks, while their secondary structures are shown as green cartoon. 2Fo-Fc simulated-annealing omit map is shown around bradykinin as blue mesh contoured at 1.5σ. Hydrogen bonds are shown as red dashed lines. (B) Surface representation of IDE-N catalytic chamber with shown positions of the active site (red surface and magenta sphere for catalytic zinc) and exosite (green surface for residues 336–342 and 359–363 of IDE). N-terminal bradykinin is shown as yellow sticks, and distance from active site to exosite is shown as dashed line.

Inspection of electron density maps from 14 datasets at resolutions from 1.9 to 3.2Å revealed peaks of non-continuous electron density in front of the active-site residues. These peaks suggested that bradykinin was incorporated in the crystals with a low occupancy (Figure S3, Supporting Information), in agreement with the low affinity inferred from the high Km observed. The size and shape of the catalytic chamber of IDE (4), and the observed position of bradykinin bound in the exosite (that is located ~30 Å distant from the catalytic Zn) (Figure 3B), suggest that IDE may bind two molecules of bradykinin at the same time (see Discussion for further consideration).

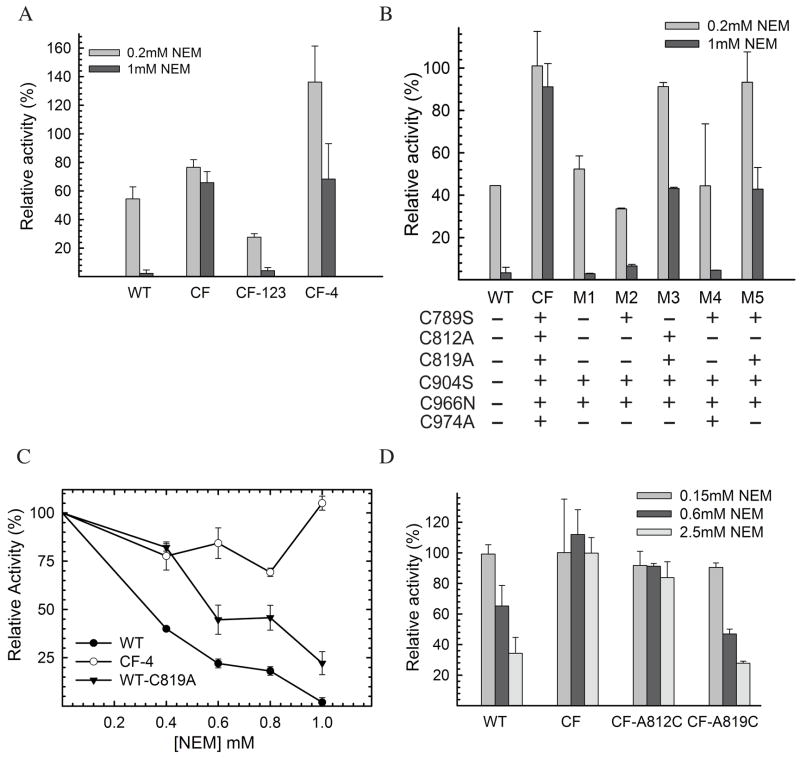

Susceptibility of IDE to alkylative damage

IDE is known to be sensitive to inhibition by sulfhydryl-directed reactions, such as alkylation (with N-ethylmaleimide [NEM]) and oxidative inactivation (H2O2) (32–34). The availability of catalytically active cysteine-free IDE poised us to test whether cysteine residues in IDE are indeed involved in the inhibition by NEM and in oxidation using a small peptide substrate as a model system. In the process of constructing the cysteine-free IDE mutant, we also made a series of mutants containing point and multiple mutations at the sites of cysteine residues (Table 1), allowing us to pinpoint the involvement of specific cysteine(s) in NEM and oxidative-mediated inhibition. Using fluorogenic bradykinin-mimetic substrate V, we found that wild-type IDE was highly sensitive to inhibition by NEM and had greater than 95% loss in its activity upon treatment with 1 mM NEM (Figure 4A). As expected, IDE mutant free of cysteine residues was relatively resistant to the inactivation by NEM. This confirms that indeed cysteine residues are responsible for the inactivation of IDE in the presence of NEM. Given that human IDE has 13 cysteines and more than one cysteine may be accounted for the NEM sensitivity, we first made two IDE mutants, IDE-CF-123 and IDE-CF-4, which have seven mutated cysteines located at domain 1, 2, and 3 or six mutated cysteines at domain 4, respectively (Table 1). We found that IDE-CF-123 remained highly sensitive to NEM while IDE-CF-4 had significantly reduced sensitivity to the treatment (Figure 4A). This finding indicates that the crucial cysteine residue(s) is located in domain 4. We also observed that IDE-CF-123 became more sensitive with respect to to IDE-WT to the inhibition by NEM, suggesting a role of cysteine(s) in domain 1, 2, 3 in the modulation of NEM sensitivity.

Figure 4.

NEM sensitivity of human IDE. Relative activities of IDE-WT, IDE-CF, IDE-CF-123, and IDE-CF-4 (A), and of IDE mutants M1-M5 (B), are shown at two concentrations of NEM (0.2 and 1 mM). Activities were measured after 1hour incubation of IDE samples partially purified by a small-scale protocol (see Experimental procedures for details). (C) NEM-concentration (0–1 mM) dependent relative activities of IDE-WT, IDE-CF-4 and IDE-WT-C819A. (D) NEM sensitivity of fully purified IDE mutants at three different concentrations of NEM (0.15, 0.6, and 2.5 mM) after 1 hour incubation. Samples shown in panel D were fully purified, in large scale, as previously reported (12) to exclude effects of contaminant from less purified samples. Relative activities are reported assuming as 100% the control reaction were each sample was incubated with buffer only. Incubations were performed mixing 1mg/ml purified IDE samples with the shown concentration of NEM, and activity was followed by measuring fluorescence as resulting from the cleavage of 0.5 μM Substrate V.

We then characterized 5 IDE mutants that have variable mutations at the six cysteine residues located in domain 4 (Table 1, and Figure 4B). We observed susceptibility to NEM for mutants M1, M2, and M4 and partial resistance for M3 and M5. This data indicates that C789, C904, C966, and C974 are not involved in the NEM sensitivity since those residues are present in IDE M1, M2, or M4. A common residue between the two NEM-resistant mutants, IDE M3 and M5 is Cys 819. This suggests a key role of this residue in NEM sensitivity. To confirm this, a mutant containing the C819A mutation in the wild-type background (IDE-WT-C819A) was constructed and tested. When compared to IDE-CF4 and IDE-WT, IDE-C819A was indeed less sensitive to NEM inactivation, confirming the important role played in the inhibition by Cys 819 (Figure 4C).

To unambiguously determine the role of specific cysteine residues of domain 4 in NEM sensitivity, we reintroduced each of the 6 cysteines into the IDE-CF background, creating 6 new single point mutants (Table 1). Initial characterization experiments were conducted on partially purified samples, and showed sensitivity to NEM of mutants A812C and A819C (Figure S4, Supporting Information). This is in direct agreement with the results obtained in the recently published study by Neant-Fery et al. (52), where the single 812C mutant of IDE, only purified through Ni-NTA chromatography, was susceptible to alkylation. However, when the same inhibition assays were performed on fully purified samples, we found that only IDE-CF-A819C is highly sensitive to the NEM inactivation (Figure 4D). This suggests that the preliminary observations from A812C were an artifact from impurities in the partially purified samples1. It is interesting to note that although located nearby, alkylation of Cys 812 does not induce a similar inhibition effect as Cys 819 (Figure 4D). Based on these findings, we concluded that in domain 4 Cys 819 is the only cysteine that plays a crucial role in the NEM-mediated inactivation of IDE.

Susceptibility of IDE to S-nitrosylation and oxidation

Inhibition of human IDE catalytic activity was further investigated using physiologically relevant modifications, oxidation by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and S-nitrosylation by S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO). H2O2 can modify residues of targeted proteins and was shown to inactivate rat IDE (32). GSNO is a potent NO donor that can covalently attach a nitrogen monoxide group to the thiol side chain of cysteines, resulting in the production of S-nitroso-thiols, which can compromise protein function (37). S-nitrosylation can also promote the formation of disulfide linkages within or between proteins (53, 54). Moreover, GSNO was shown to be the main non-protein S-nitroso-thiol source in cells and in extracellular fluids (55).

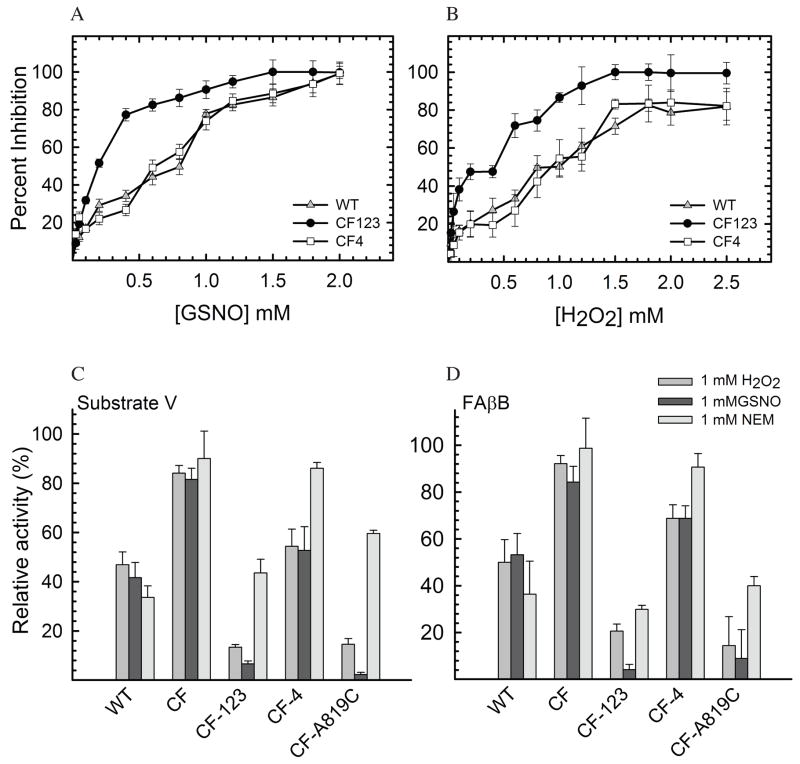

In vivo, the concentration of compounds that induce nitrosylation and oxidation of biomolecules can range in nanomolar amounts during normal conditions to as high as 100 μM during stress conditions (56, 57). Thus, we examined the concentration-dependent inhibitory effect of GSNO and H2O2, respectively, on the proteolytic activity of human IDE with respect to substrate V (Figure 5A, 5B). Our data shows that the activity of IDE can be compromised by micromolar concentrations of GSNO and H2O2. Furthermore, in Figures 5C and 5D, we compared the inhibitory effect of all 3 types of modifications (oxidation, nitrosylation and alkylation) with respect to the ability of various forms of human IDE to cleave substrate V, or FAβB. We found that wild-type IDE is sensitive to inactivation by both H2O2 and GSNO (Figure 5), while the cysteine-free form of IDE is insensitive to these treatments. This confirms the critical role of cysteines in the inactivation of IDE, with little or no contributions from other amino acids that can be modified by H2O2 or GSNO (37).

Figure 5.

GSNO and H2O2-mediated inhibition of IDE. Concentration dependent inhibition of IDE-WT, IDE-CF123 and IDE-CF4 by GSNO (A) and H2O2 (B) as measured by monitoring the degradation of substrate V. Inhibition of IDE measured by monitoring the degradation of either 0.5 μM fluorogenic substrate V (C) or 1.5 μM fluorogenic FAβB (D) in the presence of a single concentration of NEM, GSNO, and H2O2.(1 mM).

Following the same approach as applied with NEM, we wanted to pinpoint the crucial cysteine residue(s) for the sensitivity of IDE to H2O2 and GSNO. We found that IDE-CF-123 was also inactivated by H2O2 and GSNO while IDE-CF-4 was relatively resistant to such treatments (Figures 5C and 5D), indicating a similar role for cysteines in domain 4 as seen for NEM sensitivity. We then examined the effect of H2O2 and GSNO to the enzymatic activity of IDE-CF-A819C, the mutant that contains only one cysteine in position 819. We found that this mutant was highly sensitive to the treatments, again in agreement with the NEM sensitivity data. In conclusion, this indicates an unambiguous role of Cys 819 in the inactivation of IDE as induced by different mechanisms (alkylation, oxidation, nitrosylation). It is worth noting that both IDE-CF-123 and IDE-CF-A819C became more sensitive to the treatments with H2O2 and GSNO when compared to IDE-WT. This again suggests the existence of a possible protective role of cysteine residues in the domain 1, 2, and 3 among which 12 are highly conserved in mammals (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Such cysteine(s) may merely serve as stoichiometric scavengers to prevent the modification of C819 by NEM, H2O2, and GSNO. Alternatively, the modification of this residue may allosterically alter IDE structure to prevent the post-translational modification of C819 and/or structural changes mediated by C819 modification. The molecular basis for this potential protective role warrants further investigation.

DISCUSSION

Our proteomic and kinetic analyses show that IDE may participate in the catabolism of kinins. Using purified recombinant protein, we show that human IDE is able to degrade both bradykinin and kallidin and that the major cleavage site is located between the C-terminal residues Pro7-Phe8 in bradykinin and Pro8-Phe9 in kallidin. This cleavage site is the same as seen for other metalloproteases, including ACE, NEP, and ECE-1 (51). Cleaved products of bradykinin and/or kallidin result in the inactivation of kinin-mediated signaling. The physiological relevance for the cleavage of kinins by IDE remains to be established. Our kinetic analyses reveal that IDE has a low affinity for the kinins (2–7 mM).

IDE is a ubiquitously expressed metalloprotease that can be found in many cellular compartments including cytoplasm, endosomes, cell surface, and extracellular milieu. The low affinity of IDE to bradykinin will not favor the binding and degradation of kinins on cell surface or in the extracellular milieu. However, the local concentration of bradykinin released from the internalized bradykinin receptors will likely be high enough to favor its degradation by IDE (58). While IDE may negatively regulate kinin signaling, kinin signaling could inhibit IDE as well since bradykinin signaling can lead to elevated NO production (59), which could, in turn, modulate IDE activity via S-nitrosylation as the one presented in this study.

The bradykinin-bound IDE structure adds another level of complexity in the substrate binding and recognition mechanisms of IDE. Our previous structural analysis of substrate-bound IDE reveals that IDE uses an exosite to anchor the N-terminal end of its substrates 30Å away from the catalytic site, which allow multiple cleavages of substrate by IDE via a stochastic process (4, 13). In our bradykinin-bound IDE structure, we only observed the binding of bradykinin at the exosite, not at the catalytic site. This is consistent with a low binding affinity as reflected by the high Km values of IDE toward bradykinin and kallidin observed from our kinetic analyses. The cleavage site of the exosite-bound bradykinin molecule, as observed in our crystal structure, cannot reach the catalytic site of IDE. Thus, a second bradykinin molecule needs to gain access into the catalytic chamber for the degradation. Our data therefore suggests that the binding of bradykinin or other short peptides to the exosite could play a regulatory role in substrate binding and subsequent cleavage by IDE. For example, short peptides could reduce the size of the catalytic chamber of IDE, and this may enhance the substrate binding and cleavage by reducing the entropy of short peptides in the chamber. Consistent with this notion, bradykinin is shown to be an activator of IDE (16). Alternatively, it could reduce the cleavage by interfering with substrate binding.

At first glance, it is not apparent why the discovery of very low affinity substrates for IDE should be of interest at all, since their physiological significance can be dubious. However, since IDE is an enzyme capable of cleaving a large variety of substrates including peptides like insulin and amyloid-β, it is critical to understand the important features that contribute to the substrate recognition, binding, and degradation. This may provide the knowledge basis for the design of selective inhibiting or activating molecules that may modulate the function of IDE. Our IDE structures have now provided insights that clarify biochemically how IDE bind and cleave short and long peptide substrates (4, 12, 13, 18, 19). According to our findings peptides that fail to bind the catalytic site and the exosite simultaneously will have higher Km with respect to longer peptide substrates that can instead bind to the catalytic site and exosite simultaneously. For example, Km values of IDE for kinins range between 4–7 mM, while that of insulin, which has been shown to bind to both the catalytic site and the exosite simultaneously, is about five orders of magnitude lower (100 nM). Thus our studies have revealed a novel contributor to the substrate specificity of IDE: in addition to the shape of the substrate and its charge complementarity with the catalytic chamber of IDE, a further contribution to the affinity comes from the substrates’ ability to bind at the exosite of IDE.

IDE also exhibits a high rate of catalysis toward short peptides, up to 2,500 sec−1 for kinins in this study. This is in sharp contrast with the catalytic rate of IDE for insulin (approximately 0.5 min−1) (18). Our structural and biochemical analyses reveal that the closed conformation of IDE is a stable state and the switch between the closed and open states of IDE is a key regulatory step (4, 12, 13). Furthermore, the conformational switch is required in order to accommodate substrates into the catalytic cleft. Thus, the ability to gain access to the catalytic chamber and the intrinsic flexibility of peptide substrates are key factors that affect the catalytic rate of IDE. It is therefore realistic to postulate that short peptides are favored to enter into a partially opened catalytic chamber of IDE during the required conformational switch to reach the catalytic site, accounting therefore for the resulting high rate of catalysis.

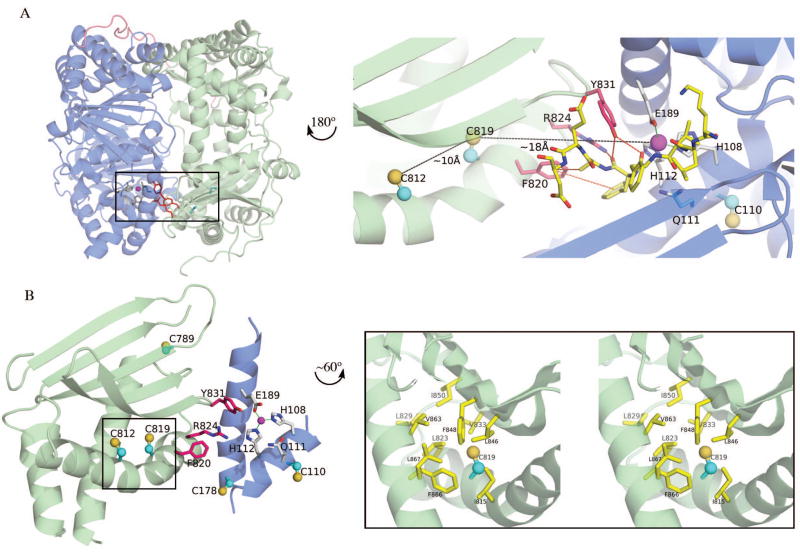

In addition to the previously reported inhibition of IDE by S-alkylation and oxidation, we report for the first time that IDE can also be significantly inhibited by S-nitrosylation, a novel thiol-directed post-translational modification of IDE, at physiologically relevant concentrations. We pinpoint Cys 819 of human IDE as playing a key role in all three modifications. Cys 819 is located inside the catalytic chamber and is ~18Å away from the catalytic zinc ion (Figure 6A). The sulfhydryl group of Cys 819 is pointing towards a hydrophobic pocket made of two phenylalanines (F848 and F866) and two leucines (L823 and L846) (Figure 6B). This pocket, with a high local hydrophobicity, is a favorable S-nitrosylation site since it would sequester and stabilize radical species as well as impede hydrolysis of SNO to a sulphenic acid (37). Cys 819 is located on a α-helix that participates in shaping the walls of the catalytic cavity of IDE (Figure 6A, 6B). This helix is positioned laterally to a 5-stranded β-sheet which is crucial for the insertion of β-strand of substrates into the catalytic site (13). Specifically, Cys 819 is near three residues (Phe 820, Arg 824, Tyr 831) that are known to play key roles in substrate binding and catalysis (13). Tyr 831 directly participates in substrate binding (Figure 6A); while the mutation Y831F does not impair the catalytic activity, the mutation Y831A results in a 5-fold decrease of activity (13). Moreover, to confirm the role of Tyr831 in stabilizing IDE-substrate interaction, the mutant Y831F was successfully crystallized and its structure solved in a substrate-free conformation (12). Arg 824 is positioned as a good candidate for stabilizing the developing negative charge on the carbonyl group of the scissile bond of the substrate, after the nucleophilic attack mediated by the catalytic water molecule. Accordingly, the mutation R824K is less detrimental for the catalytic activity than the mutation R824A (13). Finally, Phe 820 contributes to create a hydrophobic region that could also facilitate the binding of substrates in the active site (Figure 6A). This region is also part of the interface between the N- and C-domains of IDE, near the α-helix where the zinc-coordinating Glu189 is located (Figure 6A and 6B). Interestingly, with the case of physiologically relevant modifications (oxidation and S-nitrosylation), Cys 819 is not the only cysteine that has a role in the oxidation process of IDE as demonstrated in Figure 5. This is a subject that is currently under investigation.

Figure 6.

Structural analysis of the area around IDE cysteine 819. (A-Left) Cartoon representation of IDE highlighting the position of Cys 819 and Cys 812 (cyan balls and sticks), residues involved in substrate binding (red sticks), and catalytic site (magenta sphere and grey sticks). IDE-N and IDE-C are depicted as blue and green cartoons, respectively. The 28-aa loop joining IDE-N and IDE-C is shown as pink ribbon. (A-Right) Close-up view of the Cys 812-Cys819 and active site regions, after a rotation of 180° around the y-axis. Cys 812 and Cys 819 are shown as ball and sticks, their relative distance and the distance to the active site is shown as black dashes. Interactions between residues F820, R824, Y831 and Aβ1–40 from PDB ID 2G47 (13) are shown as red dashes. The position of the buried Cys 110 close to the active site is also shown. (B-Left) View of the secondary structures in the vicinity of residue Cys 819 (approximately same orientation as in A-Right). Residues and secondary structures depicted as in panel A. Location of other cysteines (110, 178, 789, and 812) not involved in inactivation of IDE is also shown as balls and sticks. (B-Right) Stereo-diagram showing close-up view of the hydrophobic local environment around the side-chain of Cys 819. Hydrophobic residues are depicted as yellow sticks. See text for details.

The tight fit of the side chain of Cys 819 into the hydrophobic pocket provides a model of how the S-alkylation by NEM, oxidation by H2O2, and S-nitrosylation by GSNO can potently inactivate the catalytic activity of IDE towards substrates mimicking both Aβ and bradykinin. All three modifications could lead to a local structural perturbation of the hydrophobic pocket, which, in turn, could disturb the network of interactions required for the substrate binding as well as the residues crucial for zinc binding, thus catalysis. Consistent with this hypothesis, the S-alkylation of IDE by NEM inhibits the enzymatic activity in a non-competitive manner (50). Furthermore, the S-nitrosylation is known to induce substantial local conformational change exemplified by the S-nitrosylation of Cys-10 of blackfin tuna myoglobin (60). The molecular details of the inhibitory mechanism of IDE by Cys-819 directed post-translational modification await future structural studies.

Supplementary Material

Multiple sequence alignment between IDE from different species (Figure S1), detail of multiple sequence alignment between IDE from different species showing conservation of cysteine residues only (Figure S2), electron density map of the final refined model IDE·BK in front of the active site region (Figure S3), NEM-inhibition assay on partially purified mutants (Figure S4), SDS-PAGE electrophoresis for selected samples purified by small-scale protocol (Figure S5). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Don Wolfgeher (Proteomic Facility, University of Chicago) and the staff at the beamline 19-ID (SBC, Argonne National Laboratory) for their assistance. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the United States Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Contract W-31-109-ENG-38.

This work was supported by American Health Assistance Foundation to E.M., and National Institutes of Health Grant GM81539 to W.J.T.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- IDE

insulin-degrading enzyme

- IDE-N

N-terminal domain of IDE

- IDE-C

C-terminal domain of IDE

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- FAβB

fluorescein-Aβ-(1–40)-Lys-biotin

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- r.m.s.d

root mean square deviation

- BK

bradykinin

- NEM

N-ethyl-maleimide

- TCEP

Tris(2-Carboxyethyl) phosphine

- ACE

angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ECE-1

endothelin-converting enzyme-1

- NEP

neprilysin

- GSNO

S–nitrosoglutathione

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- CHCA

α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- NO

nitric oxide

- SNO

S-nitrosothiol

Footnotes

During revision, Neant-Fery et al. published a study of IDE mutants (52). Based on the kinetic analysis of partially purified single cysteine IDE mutants, Neant-Fery et al. conclude that both C819 and C812 are crucial for NEM sensitivity. While our data from the partially purified proteins is consistent with their findings, the kinetic analysis from the fully purified IDE mutant refutes the role of C812 in NEM sensitivity. From subtraction, Neant-Fery et al. also infer a potential role of C178 in the inhibitory role by NEM. Unfortunately, our data does not shine light on this aspect.

References

- 1.Duckworth WC, Bennett RG, Hamel FG. Insulin degradation: progress and potential. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:608–624. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.5.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hersh LB. The insulysin (insulin degrading enzyme) enigma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2432–2434. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6238-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurochkin IV. Insulin-degrading enzyme: embarking on amyloid destruction. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:421–425. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01876-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malito E, Hulse RE, Tang WJ. Amyloid beta-degrading cryptidases: insulin degrading enzyme, presequence peptidase, and neprilysin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2574–2585. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8112-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirsky IA, Broth-Kahn RH. The inactivation of insulin by tissue extracts. I. The distribution and properties of insulin inactivating extracts (insulinase) Arch Biochem. 1949;20:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurochkin IV, Goto S. Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid peptide specifically interacts with and is degraded by insulin degrading enzyme. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:33–37. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00387-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selkoe DJ. Clearing the brain’s amyloid cobwebs. Neuron. 2001;32:177–180. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Authier F, Posner BI, Bergeron JJ. Insulin-degrading enzyme. Clin Invest Med. 1996;19:149–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller D, Baumeister H, Buck F, Richter D. Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) is a high-affinity substrate for rat insulin-degrading enzyme. Eur J Biochem. 1991;202:285–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia JV, Gehm BD, Rosner MR. An evolutionarily conserved enzyme degrades transforming growth factor-alpha as well as insulin. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:1301–1307. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.3.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose K, Savoy LA, Muir AV, Davies JG, Offord RE, Turcatti G. Insulin proteinase liberates from glucagon a fragment known to have enhanced activity against Ca2+ + Mg2+-dependent ATPase. Biochem J. 1988;256:847–851. doi: 10.1042/bj2560847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Im H, Manolopoulou M, Malito E, Shen Y, Zhao J, Neant-Fery M, Sun CY, Meredith SC, Sisodia SS, Leissring MA, Tang WJ. Structure of substrate-free human insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) and biophysical analysis of ATP-induced conformational switch of IDE. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25453–25463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen Y, Joachimiak A, Rosner MR, Tang WJ. Structures of human insulin-degrading enzyme reveal a new substrate recognition mechanism. Nature. 2006;443:870–874. doi: 10.1038/nature05143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker A. An Unusual Active Site Identified in a Family of Zinc Metalloendopeptidases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1992;89:3835–3839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li P, Kuo WL, Yousef M, Rosner MR, Tang WJ. The C-terminal domain of human insulin degrading enzyme is required for dimerization and substrate recognition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:1032–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song ES, Juliano MA, Juliano L, Hersh LB. Substrate activation of insulin-degrading enzyme (insulysin). A potential target for drug development. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49789–49794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song ES, Juliano MA, Juliano L, Fried MG, Wagner SL, Hersh LB. ATP effects on insulin-degrading enzyme are mediated primarily through its triphosphate moiety. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54216–54220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411177200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Safavi A, Miller BC, Cottam L, Hersh LB. Identification of gamma-endorphin-generating enzyme as insulin-degrading enzyme. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14318–14325. doi: 10.1021/bi960582q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song ES, Daily A, Fried MG, Juliano MA, Juliano L, Hersh LB. Mutation of active site residues of insulin-degrading enzyme alters allosteric interactions. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17701–17706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501896200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schachter M. Kinins--A Group of Active Peptides. Annual Review of Pharmacology. 1964;4:281–292. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skidgel RA, Erdos EG. Histamine, bradykinin, and their antagonists. In: LL B, Lazo JS, Parker KL, editors. Goodman & Gilman’s the Pharmacological Basis of therapeutics. McGraw-Hill Companies; 2006. pp. 629–652. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menke JG, Borkowski JA, Bierilo KK, MacNeil T, Derrick AW, Schneck KA, Ransom RW, Strader CD, Linemeyer DL, Hess JF. Expression cloning of a human B1 bradykinin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21583–21586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McEachern AE, Shelton ER, Bhakta S, Obernolte R, Bach C, Zuppan P, Fujisaki J, Aldrich RW, Jarnagin K. Expression cloning of a rat B2 bradykinin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7724–7728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marceau F, Regoli D. Bradykinin receptor ligands: therapeutic perspectives. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2004;3:845–852. doi: 10.1038/nrd1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang HY, Erdös EG. Second kininase in human blood plasma. Nature. 1967;215:1402–1403. doi: 10.1038/2151402a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deddish PA, Marcic BM, Tan F, Jackman HL, Chen Z, Erdos EG. Neprilysin Inhibitors Potentiate Effects of Bradykinin on B2 Receptor. Hypertension. 2002;39:619–623. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson GD, Stevenson T, Ahn K. Hydrolysis of peptide hormones by endothelin-converting enzyme-1. A comparison with neprilysin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4053–4058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoang MV, Turner AJ. Novel activity of endothelin-converting enzyme: hydrolysis of bradykinin. Biochem J. 1997;327(Pt 1):23–26. doi: 10.1042/bj3270023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanden C, Enquist J, Bengtson SH, Herwald H, Leeb-Lundberg LM. Kinin B2 receptor-mediated bradykinin internalization and metalloendopeptidase EP24.15-dependent intracellular bradykinin degradation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326:24–32. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.136911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachvarov DR, Houle S, Bachvarova M, Bouthillier J, Adam A, Marceau F. Bradykinin B(2) receptor endocytosis, recycling, and down-regulation assessed using green fluorescent protein conjugates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satoh T, Lipton SA. Redox regulation of neuronal survival mediated by electrophilic compounds. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shinall H, Song ES, Hersh LB. Susceptibility of amyloid beta peptide degrading enzymes to oxidative damage: a potential Alzheimer’s disease spiral. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15345–15350. doi: 10.1021/bi050650l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding L, Becker AB, Suzuki A, Roth RA. Comparison of the enzymatic and biochemical properties of human insulin-degrading enzyme and Escherichia coli protease III. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2414–2420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perlman RK, Gehm BD, Kuo WL, Rosner MR. Functional analysis of conserved residues in the active site of insulin-degrading enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21538–21544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butterfield DA, Drake J, Pocernich C, Castegna A. Evidence of oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s disease brain: central role for amyloid beta-peptide. Trends in molecular medicine. 2001;7:548–554. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foster MW, Hess DT, Stamler JS. S-nitrosylation TRiPs a calcium switch. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:570–571. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1106-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim SO, Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation: purview and parameters. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:150–166. doi: 10.1038/nrm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaneki M, Shimizu N, Yamada D, Chang K. Nitrosative stress and pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:319–329. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nathan C, Calingasan N, Nezezon J, Ding A, Lucia MS, La Perle K, Fuortes M, Lin M, Ehrt S, Kwon NS, Chen J, Vodovotz Y, Kipiani K, Beal MF. Protection from Alzheimer’s-like disease in the mouse by genetic ablation of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1163–1169. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perreault M, Marette A. Targeted disruption of inducible nitric oxide synthase protects against obesity-linked insulin resistance in muscle. Nat Med. 2001;7:1138–1143. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yasukawa T, Tokunaga E, Ota H, Sugita H, Martyn JA, Kaneki M. S-nitrosylation-dependent inactivation of Akt/protein kinase B in insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7511–7518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson GD, Ahn K. Development of an internally quenched fluorescent substrate selective for endothelin-converting enzyme-1. Anal Biochem. 2000;286:112–118. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collaborative Computational Project N. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCoy A, Grosse-Kunstleve R, Adams P, Winn M, Storoni L, Read R. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemistry quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific; San Carlos, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leissring MA, Lu A, Condron MM, Teplow DB, Stein RL, Farris W, Selkoe DJ. Kinetics of amyloid beta-protein degradation determined by novel fluorescence- and fluorescence polarization-based assays. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37314–37320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Erdös EG, Skidgel RA. Metabolism of bradykinin by peptidases in health and disease. The kinin system. In: Farmer SG, editor. Handbook of immunopharmacology. Academic press; London: 1997. pp. 111–141. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neant-Fery M, Garcia-Ordonez RD, Logan TP, Selkoe DJ, Li L, Reinstatler L, Leissring MA. Molecular basis for the thiol sensitivity of insulin-degrading enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9582–9587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801261105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stamler J, Toone EJ. The decomposition of thionitrites. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2002;6:779–785. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arnelle DR, Stamler JS. NO+, NO, and NO− donation by S-nitrosothiols: implications for regulation of physiological functions by S-nitrosylation and acceleration of disulfide formation. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1995;318:279–285. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gaston B, Reilly J, Drazen JM, Fackler J, Ramdev P, Arnelle D, Mullins ME, Sugarbaker DJ, Chee C, Singel DJ. Endogenous nitrogen oxides and bronchodilator S-nitrosothiols in human airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10957–10961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hanafy KA, Krumenacker JS, Murad F. NO, nitrotyrosine, and cyclic GMP in signal transduction. Med Sci Monit. 2001;7:801–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leeb-Lundberg LM, Marceau F, Muller-Esterl W, Pettibone DJ, Zuraw BL. International union of pharmacology. XLV. Classification of the kinin receptor family: from molecular mechanisms to pathophysiological consequences. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:27–77. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skidgel RA, Stanisavljevic S, Erdos EG. Kinin- and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor-mediated nitric oxide production in endothelial cells. Biol Chem. 2006;387:159–165. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schreiter ER, Rodriguez MM, Weichsel A, Montfort WR, Bonaventura J. S-nitrosylation-induced conformational change in blackfin tuna myoglobin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:19773–19780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brünger A. Free R value: a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature. 1992;355:472–475. doi: 10.1038/355472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multiple sequence alignment between IDE from different species (Figure S1), detail of multiple sequence alignment between IDE from different species showing conservation of cysteine residues only (Figure S2), electron density map of the final refined model IDE·BK in front of the active site region (Figure S3), NEM-inhibition assay on partially purified mutants (Figure S4), SDS-PAGE electrophoresis for selected samples purified by small-scale protocol (Figure S5). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.