Dioxygen activation by mononuclear iron oxygenases in general requires two electrons and protons to facilitate the reductive cleavage of the O-O bond and formation of a high-valent iron oxidant.[1,2] For enzymes with an iron(III) resting state, the oxidant is postulated to have a formally FeV oxidation state, e.g. FeIV(O)(porphyrin radical) for cytochrome P450[i] and FeV(O)(OH) for the Rieske dioxygenases.[ii] On the other hand, enzymes with an iron(II) resting state often require a tetrahydropterin or an α-keto acid cofactor to form an FeIV(O) intermediate.[2] Such intermediates have recently been trapped and characterized for several enzymes.[iii]

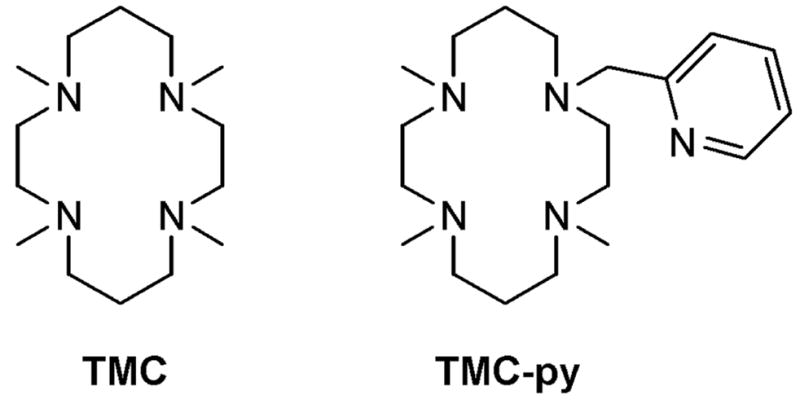

In model nonheme iron systems, there has been significant recent progress in the generation and characterization of FeIV(O) complexes, most of which were prepared by reaction of iron(II) precursors with oxygen-atom donors (e.g. peroxides, peroxyacids and ArIO).[iv] The one exception has been the formation of [FeIV(O)(TMC)(CH3CN)]2+ (1),[v] reported by Nam and co-workers in the reaction of its iron(II) precursor with O2 in the presence of alcohols or ethers.[vi] The mechanism for the formation of 1 under these conditions is not well established, but was postulated to result from O-O bond homolysis of a (μ-1,2-peroxo)diiron(III) intermediate, resembling the mechanism postulated for [FeIV(O)(TPP)] formation by the oxygenation of [FeII(TPP)].[vii] In the latter case, coordination of imidazole trans to the peroxo ligand promoted oxoiron(IV) formation. By extension, it seems plausible that binding of the added alcohol or ether to the iron may also promote the formation of 1, as FeII(TMC)(OTf)2 in the absence of such additives is air-stable.[6] In the course of our work, we appended a pyridine moiety to the TMC framework to obtain the pentadentate ligand TMC-py (Scheme 1). Its iron(II) and oxoiron(IV) complexes were synthesized and structurally characterized. Interestingly, the oxoiron(IV) complex could be generated by oxygenation of the iron(II) complex, but only in the presence of an electron (BPh4−) and a proton source. Details of this study are reported herein.

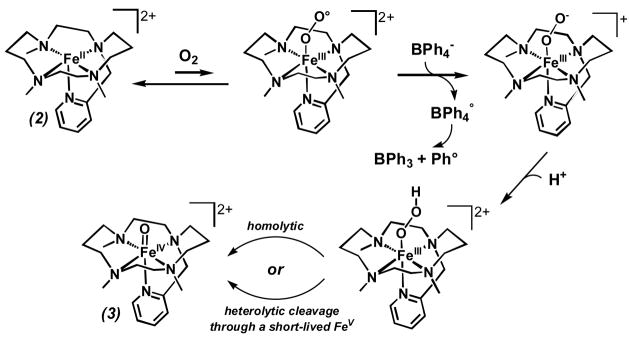

Scheme 1.

Cyclam ligands used in this study.

In our initial exploration of the chemistry of 1, our attempts to coordinate pyridine trans to the oxo unit via replacement of the MeCN ligand proved to be unsuccessful, perhaps due to the steric constraints imposed by the binding pocket. To enhance the probability of pyridine coordination we synthesized the TMC-py ligand in which one of the TMC methyl groups was replaced with a 2-pyridylmethyl arm and prepared the corresponding iron(II) complex [FeII(TMC-py)]X2 (2(X)2) (X = OTf or PF6). X-ray analysis of single crystals of 2(PF6)2 obtained from MeCN/MeOH confirmed coordination of TMC-py as a pentadentate ligand (Figure S1, Table S2),[viii] with the cyclam macrocycle adopting a trans-I configuration[ix] and the pyridine bound at the apical position of a distorted square pyramid (τ = 0.45[x]).

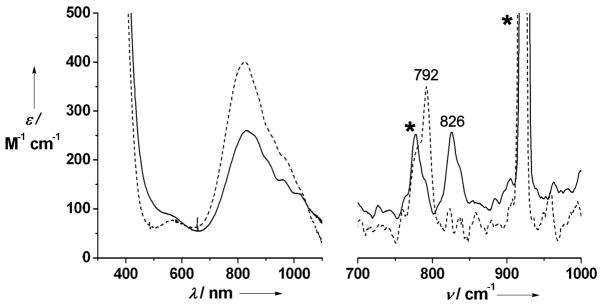

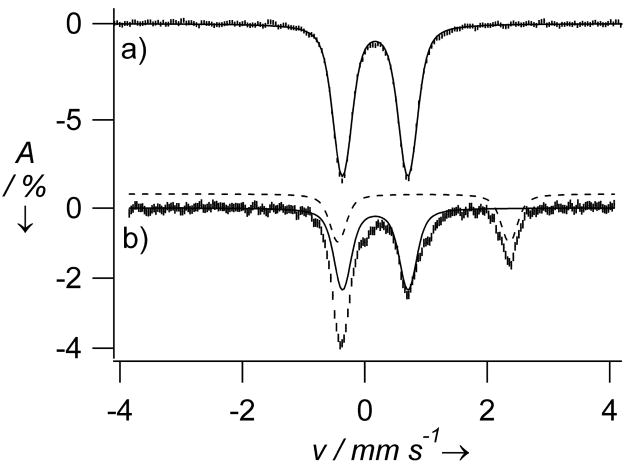

The reaction of 2 in MeCN solution at room temperature with PhIO elicited formation of a pale brown-green complex 3 in ca. 95 % yield with λmax at 834 nm (εmax = 260 M−1 cm−1) (Figure 1, left). Complex 3 can also be generated with 3 equiv H2O2, but in lower (ca. 65 %) yield. The observed near-IR bands are very similar to those of 1[xi] and assigned to ligand-field transitions, which are diagnostic of the formation of a low-spin (S = 1) oxoiron(IV) center.[xii] Consistent with this assumption, an electrospray mass spectrum of 3 exhibited a peak at m/z = 554.1 and an isotope distribution pattern in agreement with its formulation as {[FeIV(O)(TMC-py)](OTf)}+ (calculated m/z = 554.2) (Figure S2). Furthermore, a resonance Raman spectrum of 3 yielded a ν(Fe=O) at 826 cm−1 that shifted 34 cm−1 to 792 cm−1 upon 18O-labelling, as expected from Hooke’s Law (Figure 1, right). The observed frequency is 13 cm−1 lower than that observed for 1 by FT-IR spectroscopy, presumably reflecting the differing coordinative properties of an axial pyridine versus MeCN.[11] Mössbauer studies of 3 yielded a doublet with an isomer shift (δ) of 0.18 mm/s and a quadrupole splitting (ΔEQ) of 1.08 mm/s (Figure 2a), parameters similar to those of 1 (δ = 0.17 mm/s; ΔEQ = 1.24 mm/s).[11] High field studies (Figures S4 and S5; Table S1) show that 3 exhibits zero-field splitting and hyperfine parameters similar to those reported for 1.[11]

Figure 1.

Left: electronic spectra of 1 (dashed line) and 3 (solid line) in MeCN. Right: resonance Raman spectra (λex = 407 nm) of 16O-3 (solid line) and 18O-3 (dashed line) recorded in frozen solution with samples mounted on a brass cold finger. Asterisks designate features from the CH3CN solvent. The Raman samples were prepared by reaction of a 10 mM solution of 2(OTf)2 in acetonitrile with 2 equiv. of PhI(OAc)2, in the presence of 100 equivalents of H216O and H218O, respectively.

Figure 2.

4.2 K Mössbauer spectra of 3 recorded in a parallel applied field of 45 mT and generated a) by reacting 2 in MeCN with PhIO to afford a sample that contained >95% 3 and b) by reacting 2 in MeCN with O2 in the presence of 1 equiv BPh4− and 1 equiv HClO4. Solid and dashed lines indicate contributions of 3 (56% of Fe) and starting material 2 (32%), respectively.

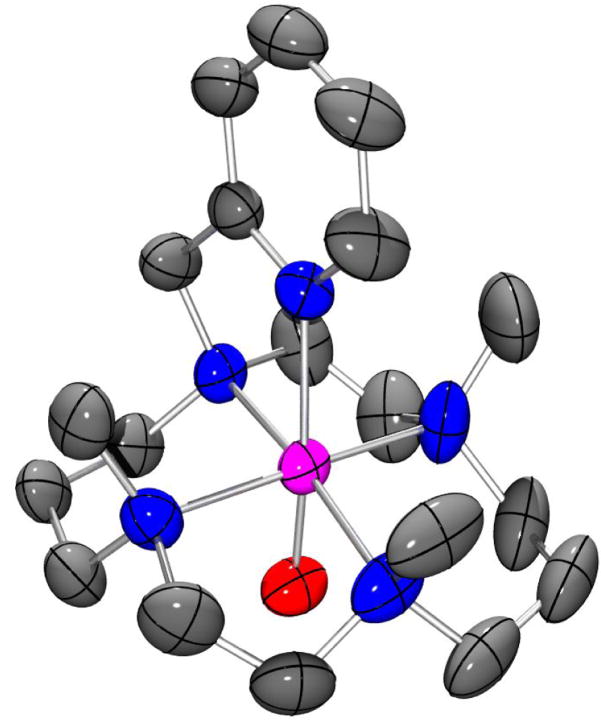

The high purity of 3 and its stability (t1/2 = 7 h at 25 °C) allowed the growth of diffraction quality crystals at −20°C from MeOH/Et2O (Table S3). The structure obtained, shown in Figure 3, represents only the third high-resolution crystal structure of an oxoiron(IV) complex reported to date[8] and conclusively demonstrates that the TMC-py ligand retains its pentadentate binding mode, and the cyclam ring its trans-I stereochemistry, upon oxidation of 2 to 3. Complex 3 has an Fe=O distance of 1.667(3) Å, which is 0.02–0.03 Å longer than those reported for 1 (1.646(3) Å)[11] and 5 (1.639(5) Å) (5 = [FeIV(O)(N4Py)]2+.[5,xiii] The Fe-Namine bonds in 3 have an average length of 2.083 Å, close to that seen for 1 (2.091 Å). In contrast, the Fe-Npy bond length in 3 is 2.118(3) Å, which is 0.06 Å longer than the axial Fe-NNCMe bond in 1,[11] despite the fact that pyridine is a much better Lewis base than MeCN. This observation may be attributed to the geometric constraints imposed by tethering of the pyridyl donor to the cyclam ring, which also manifests in a deviation of the O=Fe-Npy bond angle (169.77(13)°) from linearity. Furthermore, the Fe-Npy bond in 3 is significantly longer than the equatorial Fe-Npy bonds of 5 (ave. 1.96 Å),[13] which most probably reflects the trans effect of the oxo ligand. Metrical parameters obtained from a density functional theory geometry optimization for 3 (Figure S7, Table S4), are in good agreement with the x-ray structure. Of particular note is the close reproduction of the non-linear O=Fe-Npy bond angle and associated elongation of the Fe-Npy bond length.

Figure 3.

Thermal ellipsoid drawing of [FeIV(O)(TMC-py)](OTf)2 (3), showing 50% probability ellipsoids. The second enantiomorph, hydrogen atoms, counterions, and non-coordinating solvent molecules have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å): Fe-O, 1.667(3), Fe-Npy 2.118(3), Fe-Namine (ave) 2.083.

The susceptibility of 2 to oxidation by O2 was then investigated. While 2 was found to be air-stable at 25 °C in MeCN, it converted to 3 within minutes in the presence of 1 equiv BPh4− and 1 equiv HClO4, as indicated by the growth of the ligand-field band at 834 nm (Figure S3). The Mössbauer spectrum of an 57Fe-enriched sample obtained under these conditions (Figure 2b) showed the presence of three components: 3 (56%), unreacted 2 (32%), and an unidentified high-spin ferric byproduct (≈12%). Thus, the amount of 3 formed by oxygen activation represented about 80% of the 2 that was oxidized, a yield that is comparable to those for two oxoiron(IV) porphyrin complexes obtained by reductive activation of corresponding oxyheme precursors.[xiv]

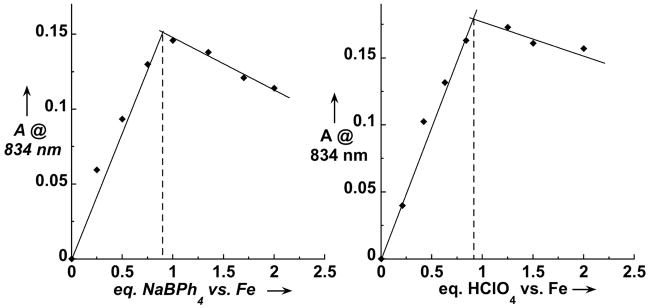

The yield of 3 obtained by oxygen activation depended on the amount of BPh4− and HClO4 added to the oxygenated solution (Figure 4) and was found to be maximal for samples containing a 1:1:1 ratio of 2:BPh4−:H+. Under these conditions, 3 exhibited a fourfold shorter lifetime (t1/2 ~ 100 min) than that prepared with H2O2 or PhIO. NMR studies of the reaction mixture showed that BPh4− had decomposed to form phenol (1 equiv) and biphenyl (0.75 equiv) byproducts, presumably derived from phenyl radicals formed upon one-electron oxidation of BPh4−. Thus, BPh4− acts as a reductant in this reaction.[xv] Additionally, we also found that ascorbic acid could be used as both an electron and a proton source in the conversion of 2 to 3 and that introduction of 0.5 equiv ascorbic acid in an ethanolic suspension to an oxygenated solution of 2 in a 1:1 mixture of MeCN and EtOH afforded 3 in ca. 55% yield.

Figure 4.

Conversion of 2 into 3 by reaction with O2 in the presence of BPh4− and H+ in CH3CN solution at 25 °C. Left: amount of 3 formed as a function of the amount of BPh4− added to a solution containing 1 equiv. of both 2 and HClO4. Right: amount of 3 formed as a function of HClO4 added to a solution containing 1 equiv. of both 2 and BPh4−.

A comparison of the dioxygen reactivity of 2 with that of the precursor to 1, [FeII(TMC)(OTf)](OTf) (4), reveals similarities and differences. Like 2, 4 was unreactive towards O2 in MeCN solvent at room temperature but converted to 1 in 75% yield within minutes in the presence of one equiv each of H+ and BPh4−. However, unlike 2, which is air stable in a 1:1 MeCN/EtOH solvent mixture, 4 readily reacted with O2 to form 1 in nearly quantitative yield in 1:1 MeCN/EtOH and other MeCN/(alcohol or ether) solvent mixtures.[6]

In the latter case, Nam and co-workers have proposed that dioxygen activation occurs via a (1,2-peroxo)diiron(III) species akin to that proposed for Fe(porphyrin) autoxidation,[7,xvi] but no detailed studies substantiating this mechanism have been reported. The fact that dioxygen activation by 4 occurs only in the presence of an alcohol or ether co-solvent raises the possibility that this additive coordinates to the iron(II) center to promote the binding and activation of the trans-bound O2. Consistent with this notion is the air stability of 2 in 1:1 MeCN/EtOH, because 2 differs from 4 in having only one available coordination site, which is presumably reserved for the binding of O2 and its subsequent activation. In the presence of H+ and BPh4−, we propose instead a reductive activation mechanism for the conversion of 2 to 3 (Scheme 2), consisting of the initial formation of an FeIII-OOH intermediate that subsequently decomposes rapidly by O-O bond cleavage to form 3. O-O bond cleavage may proceed in a homolytic fashion, but we have yet to obtain evidence for formation of a hydroxyl radical. Alternatively, heterolytic cleavage to yield a short-lived oxoiron(V) species, followed by its rapid reduction cannot be ruled out at this stage. Although the proposed FeIII-OOH intermediate has not to date been observed in the reaction of 2 with dioxygen, our mechanistic proposal is precedented by the trapping and characterization of an FeIII-OOH species supported by a related pentadentate ligand with amine, pyridine and pivaloylamido functionalities in the reaction of its iron(II) complex with O2 in the presence of BPh4− and H+.[xvii] This intermediate could alternatively be prepared from the reaction of the same FeII complex with H2O2, which allowed its unambiguous identification.[xviii]

Scheme 2.

Proposed dioxygen activation mechanism.

In summary, we have described a new oxoiron(IV) complex 3 in terms of its spectroscopic properties and high resolution crystal structure and have demonstrated its formation by reaction of its iron(II) precursor 2 with oxo-transfer agents or with O2 in the presence of a reductant and an acid. In the latter case, the requirement of a proton and an electron source is consistent with the intermediacy of a hydroperoxoiron(III) species, which bears strong parallels to the mechanistic paradigm for formation of high-valent iron oxo species, as postulated for enzymic systems such as cytochrome P450 and the Rieske dioxygenases.[1,2] Although the mechanism of formation of 3 via reaction with O2 requires greater definition and is the subject of ongoing investigations, this study represents the first example in a synthetic system of the activation of dioxygen facilitated by protons and electrons to yield high-valent nonheme iron-oxo species.

Experimental Section

2(OTf)2

Under an argon atmosphere, a solution of TMC-py (0.50 g, 1.50 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (10 mL) was added to a stirred solution of Fe(OTf)2(CH3CN)2 (0.62 g, 1.43 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (10 mL). A precipitate began to form within minutes. After overnight stirring, the volume of solvent was reduced to ca. 10 mL and the mixture filtered. The solid obtained was washed twice with small volum es of THF (5 mL) and dried under vacuum to give the product as a cream coloured powder (0.74 g, 75%). Anal. Calcd. (found) for C21H35F6FeN5O6S2: C, 36.69 (36.44); H, 5.13 (5.14); N, 10.19 (9.97). Complex 2(PF6)2 was prepared in a similar fashion. A solution of FeCl2•2H2O (0.121 g, 0.74 mmol) in MeOH (5 mL) was added to a solution of TMC-py (0.248 g, 0.74 mmol) in minimal MeOH. The yellow solution was stirred overnight and then filtered. Addition of NaPF6 (0.250 g, 1.49 mmol) in MeOH to the filtrate resulted in the formation of a pale precipitate, which was filtered and dried under vacuum to afford the product in 46% yield. Anal. Calcd. (found) for C19H35F12FeN5P2: C, 33.59 (33.41); H, 5.19 (5.15); N, 10.31 (9.95).

3(OTf)2

To a solution of 2(OTf)2 in acetonitrile/methanol was added an excess of solid iodosobenzene. Subsequent to stirring the resultant mixture at room temperature for 20 minutes, the residual iodosobenzene was removed by filtration leaving an olive-green solution of 3. Crystals of 3(OTf)2 suitable for X-ray crystallography were grown at −20°C from a methanolic solution layered with diethyl ether.

Footnotes

Dedicated to Jan Reedijk on the occasion of his retirement from Leiden University

This work is the result of equal efforts from AT and JE. It was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (GM-33162 to L.Q. and EB-001475 to E.M.) and by the French program ‘Energie, Conception Durable 2004’ (ACI BioCatOx ECD009 to F.B.). Data collection for the X-ray structure of 3(OTf)2 was performed at ChemMatCARS Sector 15, which is principally supported by the National Science Foundation/Department of Energy under grant number CHE-0535644. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02–06CH11357.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Contributor Information

Eckard Münck, Email: emunck@cmu.edu.

Lawrence Que, Jr., Email: larryque@umn.edu.

Frédéric Banse, Email: fredbanse@icmo.u-psud.fr.

References

- i.Sono M, Roach MP, Coulter ED, Dawson JH. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2841. doi: 10.1021/cr9500500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ii.Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L. Chem Rev. 2004;104:939. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- iii.Krebs C, Galonic Fujimori D, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM., Jr Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:484. doi: 10.1021/ar700066p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- iv.a) Shan X, Que L., Jr J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:421. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Que L., Jr Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:493. doi: 10.1021/ar700024g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- v.Abbreviations used. TMC = 1,4,8,11-tetramethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane, TMC-py = 1-(2′-pyridylmethyl)-4,8,11-trimethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane, TPP = dianion of mesotetraphenylporphyrin, N4Py = N,N-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)-bis(2-pyridyl)methylamine.

- vi.Kim SO, Sastri CV, Seo MS, Kim J, Nam W. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4178. doi: 10.1021/ja043083i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vii.a) Chin DH, Balch AL, La Mar GN. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:1446. [Google Scholar]; b) Chin DH, La Mar GN, Balch AL. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:4344. [Google Scholar]

- viii.Single-crystal structure and refinement data for 2(PF6)2: C19H35F12FeN5P2, Mw = 679.31, monoclinic, space group P21/c, a = 9.8438(4), b = 9.7471(5), c = 28.3527(13) Å, α = 90, β = 90.803(2), γ = 90°, V =2720.1(2) Å3, Z = 4, rcalcd = 1.651 Mgum-3, MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å, m = 0.771 mm−1), T = 100(1) K. A total of 48672 (Rint = 0.0468) independent reflections with 2q < 30.71° were collected. The resulting parameters were refined to converge at R1 = 0.0839 (I > 2q) for 392 parameters on 8407 independent reflections (wR2 = 0.2237). Max./min. residual electron density 0.733/−0.658 eÅ−3; GOF = 1.074. Single-crystal structure and refinement data for 3(OTf)2: C22H39F6FeN5O8S2, Mw = 735.55, triclinic, space group P-1, a = 9.6920(8), b = 12.2001(10), c = 13.9646(17) Å, α = 95.294(4)°, β = 108.020(4)°, γ = 98.922(4)°, V = 1533.8(3) Å3, Z = 2, rcalcd = 1.593 Mg/m3, synchrotron radiation (λ = 0.49594 Å, m = 0.232 mm−1), T = 100(2) K. A total of 6096 (Rint = 0.0275) independent reflections with 2q< 18.09° were collected. The resulting parameters were refined to converge at R1 = 0.0632 (I > 2q) for 627 parameters on 6096 independent reflections (wR2 = 0.1877). Max./min. residual electron density 1.150/−0.517 e.Å−3; GOF = 1.052. Further experimental details are provided in the Supporting Information. CCDC-683058 and 685380 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif

- ix.Bosnich B, Poon CK, Tobe ML. Inorg Chem. 1965;4:1102. [Google Scholar]

- x.Addison AW, Rao TN, Reedijk J, van Pijn J, Verschoor GC. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1984:1349. [Google Scholar]

- xi.Rohde JU, In JH, Lim MH, Brennessel WW, Bukowski MR, Stubna A, Münck E, Nam W, Que L. Science. 2003;299:1037. doi: 10.1126/science.299.5609.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xii.a) Decker A, Rohde JU, Que L, Jr, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5378. doi: 10.1021/ja0498033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Decker A, Rohde JU, Klinker EJ, Wong SD, Que L, Jr, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15983. doi: 10.1021/ja074900s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xiii.Klinker EJ, Kaizer J, Brennessel WW, Woodrum NL, Cramer CJ, Que L., Jr Angew Chem. 2005;117:3756. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:3690. [Google Scholar]

- xiv.a) Schappacher M, Weiss R. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:3736. [Google Scholar]; Mandon D, Weiss R, Franke M, Bill E, Trautwein AX. Angew Chem. 1989;101:1747. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 1989;28:1709. [Google Scholar]

- xv.a) Drew MGB, Cairns C, Stephen G, McFall S, Nelson M. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1980:2020. [Google Scholar]; b) Pal PK, Chowdhury S, Drew MGB, Datta D. New J Chem. 2002;26:367. [Google Scholar]

- xvi.Balch AL, Chan YW, Cheng RJ, La Mar GN, Latos-Grazynski L, Renner MW. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:7779. [Google Scholar]; Ghiladi RA, Kretzer RM, Guzei I, Rheingold AL, Neuhold YM, Hatwell KR, Zuberbühler AD, Karlin KD. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:5754. doi: 10.1021/ic0105866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xvii.Martinho M. Ph D thesis. Université Paris Sud 11 (Orsay); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- xviii.Martinho M, Banse F, Sainton J, Philouze C, Guillot R, Blain G, Dorlet P, Lecomte S, Girerd JJ. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:1709. doi: 10.1021/ic0623415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]