Abstract

Objective

To determine whether various levels of blood pressure (BP), particularly normal and high normal blood pressure or prehypertension predict cardiovascular mortality among urban Chinese women.

Methods

We evaluated the impact of all measures of blood pressure on total mortality and stroke and coronary heart disease (CHD)-specific mortality in a population-based cohort study, the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Included in this analysis were 68,438 women aged 40 to 70 years at baseline for whom BP was assessed.

Results

During an average of 5 years of follow-up, we identified 1,574 deaths from all causes, 247 from stroke, and 91 from CHD. Hypertension and higher levels of individual BP parameters including systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), pulse pressure (PP), and mean arterial pressure (MAP), were positively associated with all-cause, stroke, and CHD mortality (P trend <0.05 for all except for DBP and CHD mortality). Prehypertension (adjusted hazard ratio (HR adj) =1.65; 95% CI, 0.98 2.78), particularly high normal BP (HR adj =2.34; 95% CI, 1.32–4.12), was associated with an increased risk of mortality from stroke. Hypertension accounted for 9.3% of mortality from all causes, 25.5% of mortality from stroke, and 21.7% mortality from CHD. High normal BP accounted for 10.8% of mortality from stroke. Isolated SBP also predicted stroke and CHD mortality.

Conclusion

Hypertension is a significant contributor to mortality, particularly stroke and CHD mortality, among women in Shanghai. High normal BP is associated with high stroke mortality.

Keywords: blood pressure, China, cohort study, mortality, prehypertension, stroke, women

Introduction

Hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg, has been clearly associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality [1, 2]. This health burden, driven by elevated blood pressure (BP), remains high in industrialized countries [3–5] and has risen rapidly in the Asia-Pacific region in the last decade [2, 6], particularly in China, a country that is undergoing rapid industrialization and urbanization and dramatic changes in lifestyle [7–9].

It was recently suggested that prehypertension (SBP of 120 to 139 or DBP of 80 to 89 mmHg), particularly high normal BP (SBP of 130 to 139 or DBP of 85 to 89 mmHg), may also contribute to CVD risk and mortality [10–13]. The importance and magnitude of the influence of prehypertension on CVD risk and mortality have not been well characterized among women in China. Using the resources of a large, ongoing, population-based cohort of Chinese women, the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS), we comprehensively examined the role of blood pressure, especially prehypertension on total mortality, as well as on mortality from stroke and coronary heart disease (CHD).

Methods

Participants

The Shanghai Women’s Health Study is a population-based, prospective cohort study of 74,942 women (response rate of 92.7%), aged 40–70 years at recruitment (March 1997 – May 2000). Details regarding participant recruitment methods and baseline surveys have been published elsewhere [14]. Briefly, eligible women living in 7 urban districts of Shanghai were recruited into the study through in-home visits by trained medical professionals. At baseline, information about demographic characteristics, reproductive history, medical history, dietary habits, weight history, physical activity, and occupational history was collected, and weight and height measurements were taken. Information on hypertension history was collected at study enrollment by asking: “Have you ever been diagnosed with hypertension by a doctor” and “Have you ever taken antihypertensive medications?”. The study protocols were approved by the relevant committees on the use of human subjects in research, and written, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Blood pressure measurements

During the first follow-up (2000–2002), trained personnel (retired health professionals) measured blood pressure in the right arm of seated participants after a 5-minute rest by using a conventional mercury sphygmomanometer [15]. The aneroid devices were calibrated every 6 months by the staff of the Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision. An average of two BP readings was used in this analysis. The present study includes 68,438 (91.3% of 74,942) women who had both BP measurements and outcome data.

Follow-up and outcome ascertainment

Cohort members were followed through biannual in-person follow-up surveys. At each in person contact, participants or family members were asked about cardiovascular events and deaths. The response rates for first (2000–2002), second (2002–2004), and third (2004–2007) in-person follow-up surveys were 99.8%, 98.7%, and 96.7%, respectively. In addition, an annual linkage to the Shanghai Vital Statistics Registry database is conducted to identify deaths that are not captured by the in-person surveys (e.g., for participants lost to follow-up or events that occurred after the most recent survey). Positive linkages are verified by home visit. Thus, through the combination of in-person follow-up and record linkage, virtually all cohort members are being successfully followed. The underlying causes of deaths were classified using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Clinical events of interest were deaths from all causes, stroke (codes 430–438), coronary heart diseases (codes 410–414) and cancer (codes 140–208). There were a total 1,574 deaths, including 428 CVD deaths (338 from stroke and CHD, and 90 from other diseases of the circulatory system, excluding diabetes deaths), 750 cancer deaths (breast, 75; endometrial/ovarian, 113; colorectal, 117; lung, 144; stomach, 86 and 215, others), and 396 deaths due to conditions related to other body systems or causes (diabetes, 102; mental health, 8; nervous system (excluding cerebrovascular deaths), 24; respiratory, 44; digestive, 57; genitourinary, 21; ill-defined conditions, 48; injury and poisoning, 62 and other causes, 30).

Definitions and classification of blood pressure (mmHg)

Individual SBP and DBP were categorized based on the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology (ESH-ESC) guidelines [12] as follows: optimal (<120 and <80), normal (120–129 and/or 80–84), high normal (130–139 and/or 90–99), and hypertension (≥140 and/or ≥90, all grades). Subjects were also classified into four categories: normal BP (SBP <120 and DBP <80), prehypertension (SBP 120–139 or DBP 80–89), stage I hypertension (SBP 140–159 or DBP 90–99) and stage II hypertension (SBP ≥160 or DBP ≥100) according to the criteria recommended by the Joint National Committee (JNC7) on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure [10]. Pulse pressure (PP) was calculated as the difference between SBP and DBP. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated as DBP plus one-third PP. Pulse pressure and MAP were subdivided into quintiles for the whole cohort, since there is no standard “clinical” approach to categorize these measurements [16, 17]. Women with SBP ≥140 and DBP <90 and those with DBP ≥90 and SBP<140 were considered to have isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) and isolated diastolic hypertension (IDH), respectively. Women under treatment for hypertension were considered to have controlled hypertension if their SBP was less than 140 and DBP less than 90, otherwise they were considered to have uncontrolled hypertension.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the baseline characteristics of all participants were computed in means (SD) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Cox proportional hazards regression was applied to derive multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios (HRadj) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all-cause, stroke and CHD mortality in association with individual BP components, as well as for BP categories. In the regression analyses, we modeled age as a time scale in the cohort (age at first follow-up to age at exit) [18]. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the associations between mortality (all-cause, stroke and CHD) and individual BP components and categories. We evaluated the associations of mortality with demographic characteristics, education, income, occupation, BMI, WHR, history of diabetes, history of CVD (stroke and CHD), marital status, number of live births, menopausal status, use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, physical exercise and consumption of tobacco and alcohol. Of these, education, waist-to-hip ratio, cigarette smoking and history of CVD or diabetes were independent predictors of mortality and were adjusted for in subsequent analyses. Highly correlated variables such as SBP, DBP, PP, and MAP were evaluated independently. We compared models with different BP components using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) values to assess which BP measurement contained the most information. Tests for trend were performed by entering the categorical variables as continuous parameters in the model. We also assessed the relationship between BP categories and mortality in women with and without a history of CVD. Finally, we calculated population-attributable risk (PAR) [19]. All statistical tests were two-sided and performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of participants. The baseline mean age of the study population was 55.1 years, and about a half of the participants were postmenopausal (49.7%). Approximately 40% of women were high school or college/above educated, and 97% had had a live birth. At the baseline survey, 28.3% of study participants reported a history of hypertension and 8.3%, a history of CVD (stroke and CHD). The mean values of SBP and DBP at first follow up were 122.9±19.1 and 78.0±10.4 mmHg, respectively. About 21% of women in this study had used oral contraceptive pills, and 2.1% of postmenopausal women had used hormone replacement therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants, the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS)

| Characteristic | n=68 438 |

|---|---|

| mean ± SD | |

| Age (yr) | 55.1 ± 9.1 |

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) | 24.05 ± 3.4 |

| Waist-to-hips ratio (WHR) | 0.811 ± 0.05 |

| Systolic blood pressure (SBP, mmHg)† | 122.9 ± 19.1 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (DBP, mmHg) † | 78.0 ± 10.4 |

| n (%) | |

| Educational level | |

| College/above | 8 763 (12.8) |

| High school | 18 963 (27.7) |

| Middle school | 25 775 (37.7) |

| Elementary school/below | 14 925 (21.8) |

| Household income | |

| Low | 19 137 (28.0) |

| Middle | 26 909 (39.3) |

| High | 22 379 (32.7) |

| Occupation | |

| Professional | 19 124 (28.0) |

| Clerical & administrative | 14 116 (20.7) |

| Manual laborer | 34 958 (51.3) |

| Ever married | 67 870 (99.2) |

| Ever had live birth | 66 201 (96.7) |

| Menopausal status | |

| Premenopausal | 34 389 (50.3) |

| Postmenopausal | 34 035 (49.7) |

| Past use of oral contraceptives | 14 085 (20.6) |

| History of hormone replacement therapy* | 1 429 (2.1) |

| Exercised regularly in last 5 years | 24 345 (35.6) |

| Ever smoked cigarettes | 1 914 (2.8) |

| Ever drank alcohol | 1 533 (2.2) |

| History of hypertension | 19 344 (28.3) |

| History of cardiovascular disease‡ | 5 644 (8.3) |

| History of diabetes | 3 004 (4.4) |

Among postmenopausal women only

Measured at 1st follow up

Includes coronary heart diseases and stroke

Note: Missing values (<0.5%) were excluded from the calculations

Table 2 presents adjusted hazard ratios (HRadj) for all-cause, stroke and coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality in relation to individual BP parameters (SBP, DBP, PP and MAP). During an average of 5.1 years of follow-up since blood pressure measurement, 1,574 deaths (2.3% of total participants) were documented, including 247 attributed to stroke and 91 to CHD. All-cause mortality was positively and significantly associated with high SBP (≥160 mmHg) and DBP (≥90 mmHg), P trend <0.01 for both. Similarly, all-cause mortality was elevated among women in the highest quartile of PP and MAP. Higher levels of SBP (≥130 mmHg), DBP (≥85 mmHg), PP (46≥ mmHg), and MAP (95≥ mmHg) were associated with increased risk for stroke mortality (P trend <0.01 for all). A positive association was observed between CHD mortality and higher SBP (≥140 mmHg, P trend <0.01), whereas the association between CHD mortality and DBP did not reach statistical significance. The risk of CHD mortality increased with higher levels of PP or MAP (P trend <0.05 for both). There were no substantial differences in AIC values for models with different BP components (SBP, DBP, PP and MAP) and total mortality (data not shown). For stroke mortality, the models with DBP or MAP had the lowest AIC values. For CHD mortality, models with SBP and MAP had the lowest AIC values (data not shown).

Table 2.

Risk of All-cause, Stroke and Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) Mortality by Blood Pressure Parameters, the SWHS

| Total n=68 438 | All-cause, n=1 574 |

Stroke, n=247 |

CHD, n=91 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | HR (95% CI)* | No. | HR (95% CI)* | No. | HR (95% CI)* | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (SBP)†, mm Hg | |||||||

| <120 | 27 392 | 383 | 1.00 (reference) | 25 | 1.00 (reference) | 12 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 120–129 | 16 108 | 289 | 0.86 (0.73–1.00) | 27 | 1.15 (0.66–1.99) | 10 | 0.77 (0.33–1.80) |

| 130–139 | 9 581 | 249 | 0.93 (0.78–1.09) | 44 | 2.31 (1.39–3.82) | 10 | 0.88 (0.37–2.06) |

| 140–159 | 11 046 | 398 | 1.06 (0.92–1.24) | 76 | 2.76 (1.72–4.42) | 35 | 2.02 (1.02–3.99) |

| ≥160 | 4 311 | 255 | 1.41 (1.19–1.67) | 75 | 5.56 (3.44–8.97) | 24 | 2.67 (1.29–5.52) |

| P for trend | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||

| Diastolic blood pressure (DBP)†, mm Hg | |||||||

| <80 | 30 906 | 560 | 1.00 (reference) | 40 | 1.00 (reference) | 29 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 80–84 | 21 779 | 507 | 0.99 (0.88–1.12) | 72 | 1.87 (1.26–2.75) | 31 | 1.07 (0.64–1.77) |

| 85–89 | 3 134 | 81 | 1.01 (0.80–1.28) | 16 | 2.55 (1.42–4.56) | 6 | 1.24 (0.51–3.00) |

| 90–99 | 9 556 | 301 | 1.21 (1.05–1.40) | 74 | 3.78 (2.56–5.58) | 16 | 1.06 (0.57–1.96) |

| ≥100 | 3 063 | 125 | 1.61 (1.32–1.95) | 45 | 7.24 (4.70–11.2) | 9 | 1.90 (0.89–4.06) |

| P for trend | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.25 | ||||

| Pulse pressure (PP)‡, mm Hg | |||||||

| <36 | 14 226 | 177 | 1.00 (reference) | 13 | 1.00 (reference) | 5 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 36–39 | 4 705 | 62 | 0.94 (0.71–1.26) | 5 | 1.01 (0.36–2.84) | 1 | 0.50 (0.06–4.28) |

| 40–45 | 21 849 | 357 | 0.92 (0.77–1.11) | 34 | 1.11 (0.58–2.12) | 13 | 0.97 (0.34–2.75) |

| 46–53 | 13 825 | 339 | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) | 58 | 1.92 (1.04–3.56) | 17 | 1.17 (0.43–3.26) |

| ≥54 | 13 793 | 638 | 1.13 (0.94–1.35) | 137 | 2.82 (1.56–5.11) | 55 | 2.08 (0.81–5.39) |

| P for trend | 0.04 | <0.01 | 0.007 | ||||

| Mean arterial pressure (MAP)‡, mm Hg | |||||||

| <83 | 13 321 | 200 | 1.00 (reference) | 8 | 1.00 (reference) | 8 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 83–89 | 13 553 | 230 | 0.84 (0.69–1.02) | 20 | 1.74 (0.76–3.96) | 8 | 0.64 (0.24–1.72) |

| 90–94 | 14 788 | 258 | 0.78 (0.63–0.94) | 23 | 1.61 (0.71–3.61) | 9 | 0.57 (0.22–1.49) |

| 95–102 | 11 920 | 318 | 0.83 (0.69–1.00) | 45 | 2.61 (1.22–5.60) | 24 | 1.13 (0.50–2.55) |

| ≥103 | 14 856 | 568 | 1.10 (0.93–1.31) | 151 | 6.33 (3.07–13.0) | 42 | 1.41 (0.65–3.06) |

| P for trend | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to model time in the cohort (from age at 1st follow-up to age at exit); covariates included education (categorized), waist-to-hip ratio (categorized), cigarette smoking (ever/never), history of CVD (yes/no), and history of diabetes (yes/no)

SBP and DBP were categorized by ESH-ESC guidelines

PP and MAP categorized into quintile distributions

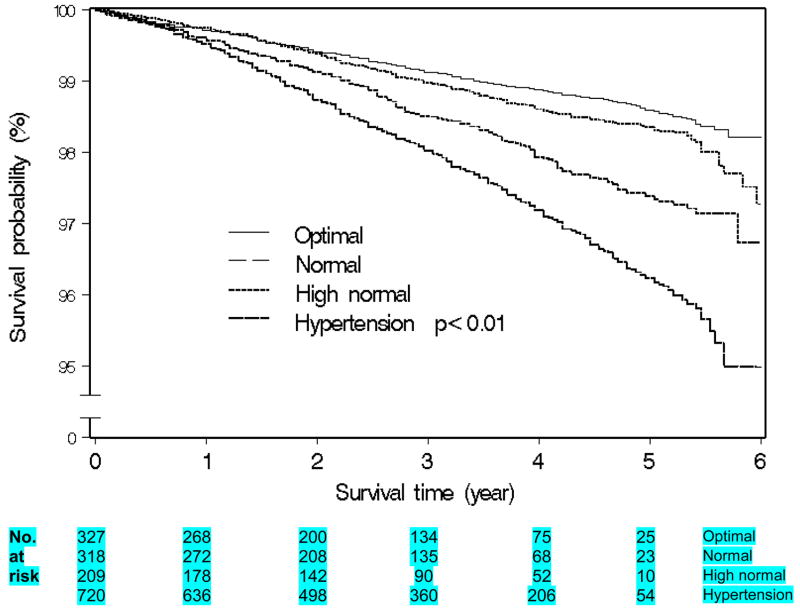

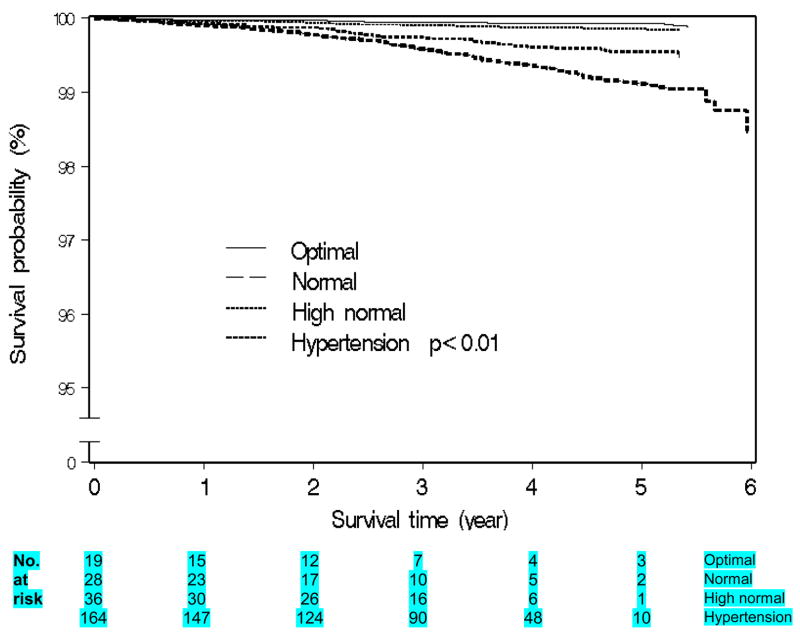

Table 3 summarizes the associations between all-cause, stroke and CHD mortality in relation to BP stages and categories. Self-reported hypertension was positively associated with mortality (1.4-fold for all-cause, 2.5-fold for stroke and 4.4-fold for CHD mortality). Prehypertension was associated with an increased risk of stroke mortality (HRadj =1.65; 95% CI, 0.98–2.78), which was primarily restricted to high normal blood pressure (HRadj =2.34; 95% CI, 1.32–4.12). Hypertension (all grades) was significantly and positively associated with all-cause, stroke and CHD mortality. Figures 1–2 show Kaplan Meier curves for all-cause and stroke morality by ESH-ESC BP categories.

Table 3.

Risk of All-cause, Stroke and Coronary Heart Diseases (CHD) Mortality by Blood Pressure (BP) Categories, the SWHS

| BP category | Subjects n=68 438 | All-cause, n= 1 574 |

Stroke, n=249 |

CHD, n=91 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | HR (95% CI)* | No. | HR (95% CI)* | No. | HR (95% CI)* | ||

| History of hypertension§ | |||||||

| No | 49 094 | 860 | 1.00 (reference) | 75 | 1.00 (reference) | 33 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 19 344 | 714 | 1.15 (1.04–1.29) | 172 | 2.85 (2.14–3.81) | 58 | 1.54 (0.97–2.44) |

| BP levels by ESH-ESC (mm Hg) | |||||||

| <120/80 (optimal) | 22 978 | 327 | 1.00 (reference) | 19 | 1.00 (reference) | 11 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 120–129/80–84 (normal) | 18 666 | 318 | 0.85 (0.72–1.00) | 28 | 1.21 (0.67–2.17) | 10 | 0.68 (0.29–1.61) |

| 130–139/85–89 (high normal) | 8 023 | 209 | 0.87 (0.73–1.05) | 36 | 2.34 (1.32–4.12) | 9 | 0.82 (0.33–1.99) |

| ≥140/90 (all grade hypertension) | 18 771 | 720 | 1.14 (1.00–1.32) | 164 | 3.90 (2.39–6.39) | 61 | 1.95 (1.00–3.79) |

| BP levels by JNC7 (mm Hg) | |||||||

| <120/80 (normal) | 22 978 | 327 | 1.00 (reference) | 19 | 1.00 (reference) | 11 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 120–139/80–89 (prehypertension) | 26 689 | 527 | 0.86 (0.75–0.99) | 64 | 1.65 (0.98–2.78) | 19 | 0.74 (0.35–1.57) |

| 140–159/90–99 (stage I hypertension) | 13 041 | 428 | 1.04 (0.89–1.21) | 80 | 2.91 (1.74–4.88) | 34 | 1.70 (0.84–3.42) |

| ≥160/100 (stage II hypertension) | 5 730 | 292 | 1.36 (1.15–1.61) | 84 | 5.76 (3.43–9.65) | 27 | 2.42 (1.17–5.01) |

| Isolated hypertension (mm Hg) | |||||||

| <120/80 | 22 978 | 327 | 1.00 (reference) | 19 | 1.00 (reference) | 11 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 120–139/80–89 | 26 689 | 527 | 0.86 (0.75–0.99) | 64 | 1.63 (0.97–2.74) | 19 | 0.75 (0.35–1.58) |

| ≥140 and ≥90 | 9 205 | 359 | 1.27 (1.08–1.48) | 106 | 5.39 (3.26–8.93) | 23 | 1.70 (0.81–3.58) |

| ≥140/<90 (isolated systolic hypertension) | 6 152 | 294 | 1.04 (0.88–1.23) | 45 | 2.29 (1.31–3.99) | 36 | 2.45 (1.21–4.97) |

| <140/≥90 (isolated diastolic hypertension) | 3 414 | 67 | 1.05 (0.81–1.37) | 13 | 3.27 (1.61–6.64) | 2 | 0.80 (0.18–3.63) |

| Hypertension by history and BP measurement (mm Hg) | |||||||

| No history of hypertension and BP <140/90 | 41 523 | 614 | 1.00 (reference) | 41 | 1.00 (reference) | 21 | 1.00 (reference) |

| No history of hypertension and BP ≥140/90 | 7 571 | 246 | 1.25 (1.07–1.45) | 34 | 2.42 (1.52–3.84) | 12 | 1.52 (0.74–3.12) |

| Controlled hypertension† | 8 144 | 240 | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) | 42 | 2.50 (1.60–3.91) | 9 | 0.73 (0.33–1.63) |

| Uncontrolled hypertension† | 11 200 | 474 | 1.32 (1.16–1.50) | 130 | 4.81 (3.32–6.98) | 49 | 2.42 (1.40–4.19) |

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to model time in the cohort (from age at 1st follow-up to age at exit); covariates included education (categorized), waist-to-hip ratio (categorized), cigarette smoking (ever/never), history of CVD (yes/no), and history of diabetes (yes/no)

Self-reported

Self-reported history of hypertension with use of antihypertensive medications and measured BP <140/90 or ≥140/90 mm Hg

Figure 1.

Kaplan-meier graph of All-cause mortality survival among women by BP category (ESH-ESC)

Figure 2.

Kaplan-meier graph of Stroke mortality survival among women by BP category (ESH-ESC)

Stage I hypertension (by JNC7 category) was a predictor for stroke mortality (HRadj=2.91; 95% CI, 1.74–4.88), but not for all-cause or CHD mortality. Women with isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) had an increased risk of dying from stroke or CHD (HRadj =2.29; 95% CI, 1.31–3.99 or HRadj =2.45; 95% CI, 1.21–4.97, respectively). Women with isolated diastolic hypertension (IDH) were at high risk of dying from stroke (HRadj =3.27; 95% CI, 1.61–6.64). Women with no history of hypertension and BP of 140/90 mmHg had an increased risk of all-cause mortality (HRadj =1.25; 95% CI, 1.07–1.45), particularly stroke (HRadj =2.42; 95% CI, 1.52–3.84), while women with uncontrolled hypertension were at a higher risk of all-cause (HRadj =1.32; 95% CI, 1.16–1.50), stroke (HRadj =4.81; 95% CI, 3.32–6.98) and CHD (HRadj=2.42; 95% CI, 1.40–4.19) mortality compared to those with normal BP. Furthermore, women who had controlled hypertension also had an elevated risk of stroke mortality (HRadj =2.50; 95% CI, 1.63–3.95).

We carried out additional analyses stratified by history of CVD and found hypertension was strongly associated with increased risk of stroke mortality in both women with and without a history of CVD at study enrollment (HRadj =3.68; 95% CI 2.12–6.38 and HRadj =4.65; 95% CI 1.45–14.9, respectively). We observed no interaction of history of CVD and BP with survival (data not shown).

We further evaluated the association of each 5 mmHg increase in all BP parameters with mortality among prehypertensive women. Each 5 mmHg increment in SBP or MAP was associated with increased risk of stroke mortality (HRadj =1.25; 95% CI, 1.03–1.51 for SBP; HRadj =1.33; 95% CI, 1.00–1.77 for MAP). No other significant difference was observed (data not shown).

Additionally, we estimated the population attributable risk for mortality due to blood pressure categories (Table 4). Hypertension (all grades) accounted for 9.3% of all-cause, 25.5% of stroke and 21.7% of CHD mortality, respectively. High normal BP accounted for 10.8% of stroke mortality.

Table 4.

Population Attributable Risk† (PAR) of All-cause, Stroke and CHD mortality associated with Blood Pressure (BP) category by ESH-ESC, the SWHS

| PAR† (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP (mm Hg) | Subjects n=68 438 | All-cause n=1 574 | Stroke n=247 | CHD n=91 |

| <120/80 (optimal) | 22 978 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 120–129/80–84 (normal) | 18 666 | - | - | - |

| 130–139/85–89 (high normal) | 8 023 | - | 10.8 | - |

| ≥140/90 (hypertension, all grade) | 18 771 | 9.3 | 25.5 | 21.7 |

PAR was estimated by using prevalence and hazard ratios (HR) in Table 3

Last, we evaluated the association of BP measurements with total cancer mortality andmortality from the most common cancers. Our analyses did not show strong associations between total cancer, colorectal, stomach or lung cancer mortality with BP using ESH-ESC criteria. We found a positive association between stage II hypertension and breast cancer mortality (HRadj =2.21; 95% CI, 1.10–3.74 or 2.03; 0.99–4.14, respectively). Hypertension was also associated with endometrial/ovarian cancer mortality. We did not find significant associations between BP and risk of diabetes (HRadj =1.25, 95% CI, 0.69–2.31), nerve, digestive or respiratory system mortality (data not shown).

Discussion

In this large, population-based cohort study, we found that individual BP parameters, including SBP, DBP, PP and MAP, were positively associated with all-cause and CVD mortality. We found no substantial differences between these BP measurements in predicting all-cause mortality. It appears that DBP and MAP may be slightly more informative in predicting stroke mortality and SBP and MAP, in predicting CHD mortality. Women with hypertension (all grades) were at a greater risk of all-cause and CVD mortality. Isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) was associated with an increased risk of CVD mortality. Women with controlled or uncontrolled hypertension were both at an increased risk of stroke mortality, although the risk was higher for uncontrolled hypertension. More importantly, we found that high normal BP was positively associated with stroke mortality and accounted for 10.8% of stroke-related deaths in our study population.

Our results on SBP and DBP and mortality are comparable with many prior reports [20–23]. However, not all studies have reported the same level of association between individual parameters of BP measurement and cardiovascular mortality [17, 22, 24]. A meta-analysis of 61 prospective observational studies has suggested that the average of SBP and DBP were slightly more informative than either alone, and PP was the least informative for CVD mortality [1]. Other studies, however, have reported that DBP plays a less important role in CVD mortality than does SBP [7, 25, 26] and speculated that the lower significance of DBP as a CVD mortality risk factor is associated with the strong impact of antihypertensive treatment on DBP, which enhances the role of SBP and PP [17, 22]. Recent studies [4, 27–29], including the Framingham Heart Study [23, 24] and the Multiple Risk Intervention Trial (MRFIT) [16], have indicated the importance of PP in risk of CHD mortality, particularly higher levels of PP. A cross-sectional study from rural China showed MAP to be a significant marker of stroke (both ischemic and hemorrhagic) [30], similar to our findings. It was suggested that MAP is the cerebral perfusion pressure that characterizes intracranial pressure, as well as the cerebral circulation [21, 31].

In addition to the well-known impact of hypertension on all-cause and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [3, 6, 9], it was recently suggested that prehypertension may increase cardiovascular risk [1, 32, 33]. This hypothesis was confirmed in several other cohort studies as in this study. In the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiologic Follow-up Study (NHEFS) for non-elderly (age ≤65 years), prehypertensive people both SBP and DBP were significantly associated with increased risk of CVD mortality [34]. A Swedish prospective cohort study also reported an increased incidence of stroke in both female and male subjects (45 to 73 years old) with BP of 130–139/85–89 mmHg [35]. BP of 130–139/85–89 mmHg was found to be associated with an increased risk of developing hypertension or a major cardiovascular event (stroke, myocardial infarction, or coronary revascularization) in both the Women’s Health Study of over 39,000 subjects during 10.2 years follow-up [11] and the Women’s Health Initiative of 60,785 postmenopausal women during 7.7 years follow-up [13]. A meta-analysis has also shown that SBP/DBP ≥115/75 was related to total vascular mortality [1]. A overview of prospective cohort studies and updated meta-analysis of randomized control trials has shown the potential benefits of lowering SBP to 115 mmHg [36]. Thus, despite existing controversies about the clinical management of normal and high normal BP or prehypertension for prevention of cardiovascular disease [10, 37], our study and other epidemiological evidence indicate the importance of recognizing cardiovascular risk associated with high normal BP when making treatment decisions [12]. Intervention studies are warranted in order to assess whether treating high normal BP would result in a reduction of stroke mortality.

In our study, we did not find that elevated blood pressure was related to overall cancer mortality. The positive association between hypertension and breast and endometrial cancer mortality are in line with earlier studies showing that hypertension was related to the risk of these cancers [38–40]. Obesity, a major risk factor for hypertension and a prognostic factor for breast cancer and endometrial cancer [40–42], is likely be one of the mediators.

Strengths of our study include the large sample size, high response (92.7% at baseline) and follow-up (91.3% at 3rd follow-up) rates, and the prospective study design. Home-based BP measurements were taken by medical professionals, which have repeatedly been shown in previous studies to have ‘a better prognostic accuracy than office blood pressure measurement’ [43, 44]. The use of BP values measured on a single occasion is a limitation which may have led an underestimation of the association. The relatively small number of CVD mortality events in this study prevented us carrying out more detailed subgroup analyses, such as by age group or menopausal status. A lack of information on contributing causes of death limited our ability to evaluate the effect of BP on causes of death independent from its effect on cardiovascular death.

In conclusion, we found in a large, population-based cohort study that hypertension was responsible for 9.3% of mortality due to all causes, 25.5% of mortality due to stroke, and 21.7% of mortality due to CHD in women in Shanghai. High normal BP accounted for 10.8% of stroke mortality. Given the prediction that CVD will increase substantially in China in the near future [6], our study emphasizes the need to develop a comprehensive and effective BP management strategy to reduce CVD mortality.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants R01CA70867 and R01 HL079123 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), USA. The authors are in debted to the participants and staff members of the Shanghai Women’s Health Study and thank Ms. Bethanie Hull for technical assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BP

blood pressure

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- PP

pulse pressure

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- ISH

isolated systolic hypertension

- IDH

isolated diastolic hypertension

- SWHS

Shanghai Women’s Health Study

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- JNC7

Joint National Committee

- ESH-ESC

European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9349):1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawes CM, Vander HS, Rodgers A. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371(9623):1513–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Banegas JR, Giampaoli S, Hense HW, Joffres M, et al. Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada, and the United States. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2363–2369. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panagiotakos DB, Kromhout D, Menotti A, Chrysohoou C, Dontas A, Pitsavos C, et al. The relation between pulse pressure and cardiovascular mortality in 12,763 middle-aged men from various parts of the world: a 25-year follow-up of the seven countries study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(18):2142–2147. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.18.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qureshi AI, Suri MF, Kirmani JF, Divani AA. Prevalence and trends of prehypertension and hypertension in United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 1976 to 2000. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11(9):CR403–CR409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martiniuk AL, Lee CM, Lawes CM, Ueshima H, Suh I, Lam TH, et al. Hypertension: its prevalence and population-attributable fraction for mortality from cardiovascular disease in the Asia-Pacific region. J Hypertens. 2007;25(1):73–79. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328010775f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang XH, Longstreth WT, Jr, Li SC, Kronmal RA, Cheng XM, Wang WZ, et al. Longitudinal study of blood pressure and stroke in over 37,000 People in China. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2001;11(3):225–229. doi: 10.1159/000047643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He J, Gu D, Wu X, Reynolds K, Duan X, Yao C, et al. Major causes of death among men and women in China. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(11):1124–1134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa050467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang XF, Attia J, D’Este C, Ma XY. The relationship between higher blood pressure and ischaemic, haemorrhagic stroke among Chinese and Caucasians: meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13(3):429–437. doi: 10.1097/00149831-200606000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conen D, Ridker PM, Buring JE, Glynn RJ. Risk of cardiovascular events among women with high normal blood pressure or blood pressure progression: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2007;335(7617):432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39269.672188.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mancia G, De BG, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, et al. 2007 ESH-ESC Practice Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: ESH-ESC Task Force on the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2007;25(9):1751–1762. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f0580f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsia J, Margolis KL, Eaton CB, Wenger NK, Allison M, Wu L, et al. Prehypertension and cardiovascular disease risk in the Women’s Health Initiative. Circulation. 2007;115(7):855–860. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.656850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng W, Chow WH, Yang G, Jin F, Rothman N, Blair A, et al. The Shanghai Women’s Health Study: rationale, study design, and baseline characteristics. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(11):1123–1131. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perloff D, Grim C, Flack J, Frohlich ED, Hill M, McDonald M, et al. Human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometry. Circulation. 1993;88(5 Pt 1):2460–2470. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Domanski M, Mitchell G, Pfeffer M, Neaton JD, Norman J, Svendsen K, et al. Pulse pressure and cardiovascular disease-related mortality: follow-up study of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) JAMA. 2002;287(20):2677–2683. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.20.2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Psaty BM, Furberg CD, Kuller LH, Cushman M, Savage PJ, Levine D, et al. Association between blood pressure level and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and total mortality: the cardiovascular health study. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(9):1183–1192. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korn EL, Graubard BI, Midthune D. Time-to-event analysis of longitudinal follow-up of a survey: choice of the time-scale. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(1):72–80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruzzi P, Green SB, Byar DP, Brinton LA, Schairer C. Estimating the population attributable risk for multiple risk factors using case-control data. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122(5):904–914. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antikainen RL, Jousilahti P, Vanhanen H, Tuomilehto J. Excess mortality associated with increased pulse pressure among middle-aged men and women is explained by high systolic blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2000;18(4):417–423. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sesso HD, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, Gaziano JM, Manson JE, et al. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, pulse pressure, and mean arterial pressure as predictors of cardiovascular disease risk in Men. Hypertension. 2000;36(5):801–807. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.5.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borghi C, Dormi A, L’Italien G, Lapuerta P, Franklin SS, Collatina S, et al. The relationship between systolic blood pressure and cardiovascular risk--results of the Brisighella Heart Study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2003;5(1):47–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2003.01222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haider AW, Larson MG, Franklin SS, Levy D. Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse pressure as predictors of risk for congestive heart failure in the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(1):10–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franklin SS, Khan SA, Wong ND, Larson MG, Levy D. Is pulse pressure useful in predicting risk for coronary heart Disease? The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 1999;100(4):354–360. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hilden T. The influence of arterial compliance on diastolic blood pressure and its relation to cardiovascular events. J Hum Hypertens. 1991;5(3):131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smulyan H, Safar ME. The diastolic blood pressure in systolic hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(3):233–237. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-3-200002010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang J, Madhavan S, Alderman MH. Pulse pressure: a predictor of cardiovascular mortality among young normotensive subjects. Blood Press. 2000;9(5):260–266. doi: 10.1080/080370500448641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glynn RJ, Chae CU, Guralnik JM, Taylor JO, Hennekens CH. Pulse pressure and mortality in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(18):2765–2772. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swaminathan RV, Alexander KP. Pulse pressure and vascular risk in the elderly: associations and clinical implications. Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 2006;15(4):226–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1076-7460.2006.04774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng L, Sun Z, Li J, Yu J, Wei Y, Zhang X, et al. Mean arterial pressure: a better marker of stroke in patients with uncontrolled hypertension in rural areas of China. Intern Med. 2007;46(18):1495–1500. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Trijp MJ, Grobbee DE, Peeters PH, van Der Schouw YT, Bots ML. Average blood pressure and cardiovascular disease-related mortality in middle-aged women. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(2 Pt 1):197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liszka HA, Mainous AG, III, King DE, Everett CJ, Egan BM. Prehypertension and cardiovascular morbidity. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(4):294–299. doi: 10.1370/afm.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mainous AG, III, Everett CJ, Liszka H, King DE, Egan BM. Prehypertension and mortality in a nationally representative cohort. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(12):1496–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenberg J. Are blood pressure predictors of cardiovascular disease mortality different for prehypertensives than for hypertensives? Am J Hypertens. 2006;19(5):454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li C, Engstrom G, Hedblad B, Berglund G, Janzon L. Risk factors for stroke in subjects with normal blood pressure: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2005;36(2):234–238. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000152328.66493.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Feigin VL, Rodgers A. Blood pressure and stroke: an overview of published reviews. Stroke. 2004;35(3):776–785. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000116869.64771.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mancia G, Grassi G. Joint National Committee VII and European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology guidelines for evaluating and treating hypertension: a two-way road? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16 (Suppl 1):S74–S77. doi: 10.1681/asn.2004110963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Largent JA, McEligot AJ, Ziogas A, Reid C, Hess J, Leighton N, et al. Hypertension, diuretics and breast cancer risk. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20(10):727–732. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindgren A, Pukkala E, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A. Incidence of breast cancer among postmenopausal, hypertensive women. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(3):641–644. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furberg AS, Thune I. Metabolic abnormalities (hypertension, hyperglycemia and overweight), lifestyle (high energy intake and physical inactivity) and endometrial cancer risk in a Norwegian cohort. Int J Cancer. 2003;104(6):669–676. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stumpe KO. Hypertension and the risk of cancer: is there new evidence? J Hypertens. 2002;20 (4):565–567. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200204000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furberg AS, Veierod MB, Wilsgaard T, Bernstein L, Thune I. Serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, metabolic profile, and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96 (15):1152–1160. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bobrie G, Chatellier G, Genes N, Clerson P, Vaur L, Vaisse B, et al. Cardiovascular prognosis of “masked hypertension” detected by blood pressure self-measurement in elderly treated hypertensive patients. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1342–1349. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.11.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Staessen JA, Den HE, Celis H, Fagard R, Keary L, Vandenhoven G, et al. Antihypertensive treatment based on blood pressure measurement at home or in the physician’s office: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(8):955–964. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.8.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]