Abstract

It is well established that intrauterine infections can pose a threat to pregnancy by gaining access to the placenta and fetus, and clinical studies have strongly linked bacterial infections with preterm labor. While Chlamydia trachomatis (C. trachomatis; Ct) can infect the placenta and decidua, little is known about its effects on trophoblast cell immune function. We have demonstrated that Ct infects trophoblast cells to form inclusions, and completes the life cycle within these cells by generating infectious elementary bodies. Moreover, infection with Ct leads to differential modulation of the trophoblast cell's production of cytokines and chemokines. Using two human first trimester trophoblast cell lines, Sw.71 and H8, the most striking feature we found was that Ct infection results in a strong induction of IL-1β secretion, and a concomitant reduction in MCP-1 (CCL2) production in both cell lines. In addition, we have found that Ct infection of the trophoblast results in the cleavage and degradation of NFκB p65. These findings suggest that the effect of a Chlamydia infection on trophoblast secretion of chemokines and cytokines involves both activation of innate immune receptors expressed by the trophoblast, and virulence factors secreted into the trophoblast by the bacteria. Such altered trophoblast innate immune responses may have a profound impact on the microenvironment of the maternal-fetal interface, and this could influence pregnancy outcome.

Keywords: Reproductive Immunology, Bacterial, Chemokines, Cytokines

Introduction

Chlamydia trachomatis (Ct) is the most common bacterial sexually transmitted disease in the US. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 2.8 million people are infected with Chlamydia each year, and the highest incidence is among young women between the ages of 15 and 24 (1). The majority of women with Chlamydia are asymptomatic and, therefore, are often unaware that they are infected. This makes for a major clinical problem, since Ct infection can have a serious impact on a women's reproductive potential, with 40% of cases leading to pelvic inflammatory disease. Of these, about 1% become infertile and may have an ectopic pregnancy (2, 3). In addition, there is growing evidence to suggest that a Ct infection may also be associated with pregnancy complications, such as still birth, spontaneous abortion and prematurity (4-7).

C. trachomatis exists as a number of serovars. Serovars A - C cause occular disease; serovars D - K infect the urogenital tract; and serovars L1 - L3 cause Lymphogranuloma venerium (8). Thus, C. trachomatis can infect a wide range of cell types, including epithelial cells of the eye and the genital tract, monocytes, and fibroblasts. In addition, clinical studies have demonstrated that Ct can infect the placenta and decidua (9-12). However, little is known about the impact this infection has on the function of these gestational tissues.

C. trachomatis is an obligate intracellular gram negative bacteria that initially infects cells as a metabolically inert, elementary body (EB). Once inside the cytoplasm of the target cell, the EB converts into the reticuloid body (RB), which is metabolically active and is the replicating form. RB replication occurs within a specialized vacuole, known as an inclusion (13). Following replication, the RBs redifferentiate into EBs, which then get released from the host cell, either by cell lysis or by extrusion of the inclusion, to infect neighboring cells (14). During an infection, Chlamydia modifies the host cell by secreting virulence factors into the cell's cytoplasm using a type III secretion system. This can arise upon either binding of the EB to cells; or while the organism is growing within the inclusion (15). Some virulence factors prevent fusion of the inclusion with cell's lysosomes and block apoptosis (16), while other factors act as proteases, such as CPAF, that degrades transcription factors important for the upregulation of MHC class I and class II and keratin. Another protease encoded by CT441 gene, cleaves NFκB p65, thus interfering with the NFκB signaling pathway (17, 18).

It is well established that intrauterine bacterial infections can pose a threat to pregnancy by gaining access to the placenta; and clinical studies have strongly linked bacterial infections with preterm labor (19). While the precise mechanisms by which an infection can lead to such pregnancy complications remains largely undefined, excessive inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface are thought to be a key contributor in a compromised pregnancy. One hypothesis as to how this inflammation arises, is that through the expression of the innate immune pattern recognition receptors, the placenta has the ability to recognize and respond to microorganisms that may pose a threat to embryo and pregnancy outcome (20). Since, the interaction between the maternal immune system and the invading trophoblast at the fetal-maternal interface may be crucial for successful pregnancy; alterations in this type of cross-talk, as in the case of infection-triggered inflammation, could result in a complicated pregnancy (21).

We have previously reported on the role of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in the regulation of immune cell migration by first trimester trophoblast cells after stimulation of TLR-4 by bacterial LPS and TLR-3 receptor by poly(I:C) (22). Activation of these receptors lead to secretion of specific cytokines/chemokines by the trophoblast, which in turn can influence immune cell migration towards the trophoblast (22), as well as the immune cell function (23). This work established a role for the innate immune pattern recognition receptors in trophoblast activation by microbial components, and their subsequent communication with the maternal immune system. In the current study, we have extended this work by examining C. trachomatis infection of first trimester trophoblasts. By studying infection with a whole organism, rather than using bacterial components, we hope to obtain a greater understanding of trophoblast responses to Chlamydia infection. We have found, using two human first trimester trophoblast cells lines, specific modulation of trophoblast cytokine and chemokine production after infection with C. trachomatis. We have found that following C. trachomatis infection, trophoblast cells secrete elevated levels of some factors, such as the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β; while the secretion of chemokines normally produced by the trophoblast, such as MCP-1 (CCL2), is inhibited. In addition, we have found that C. trachomatis infection of trophoblast cells results in the cleavage of NFκB p65. These findings support our hypothesis that the effect of a Chlamydia infection on chemokine/cytokine secretion by the trophoblast may be the result of a dynamic interaction of activation of innate immune receptors expressed by the trophoblast and virulence factors secreted into the trophoblast by the bacteria. Such altered trophoblast innate immune responses may have a profound impact on the microenvironment of the maternal-fetal interface, and this could influence pregnancy outcome.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Two human first trimester trophoblast cell lines were used in this study. The SV40-transformed HTR8 cells (hereon referred to as H8), were a gift from Dr C. Graham (Queens University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada) (24), and the Sw.71 cells, were immortalized by telomerase-mediated transformation (23, 25, 26). The H8 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) and the Sw.71 cells were grown in high glucose DMEM (Gibco). Both media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, South Logan, UT), 10mM Hepes, 0.1mM MEM non-essential amino acids, 1mM sodium pyruvate, 100nm penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). The Human derived cervical carcinoma cell line, HeLa, was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and was grown in Iscove's modified high glucose Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine serum, 1% non-essential amino acids, and penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). All cell lines were maintained at 37°C/5% CO2. As shown in our published studies, we find these cell lines to perform similarly to primary trophoblast cultures (26, 27).

Chlamydia trachomatis culture

Chlamydia trachomatis serovars D and L1 were a gift from Dr. Robert DeMars (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI). C. trachomatis was propagated in HeLa cells grown in antibiotic-free DMEM (Gibco) as previously described (28). Briefly, Ct was propagated by first rinsing the flask with Ca-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then infecting HeLa cell monolayers (∼ 80% confluency) in a 75cm2 flask (Falcon, Becton Dickinson, NJ) by rocking (2 excursions/minute on a Bellco rocker platform) for 1 hour at room temperature followed by resting for 1 hour. The cells were infected at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 in a 3ml volume with DMEM. Following this, the medium was aspirated and replaced with fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1μg/ml cyclohexamide (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). The infected cells were then transferred into a humidified incubator at 37°C/5% CO2 for 48 hours. Next, the HeLa cells were washed with PBS, collected by scrapping, and then transferred into 14ml round-bottom tubes (Falcon). The tubes (2ml/tube) were then placed in ice water in a disruptor cup horn of a sonicator (Branson Digital Sonicator/S250D). The cells were sonicated at 200W and 78% amplitude during three rounds of 20 seconds and one last round of 10 seconds. The cells were then centrifuge for 10 minutes at 200g and 4°C. The supernatant was collected and further centrifuged for one hour at 30,000g at 4°C in a Sorvall centrifuge The supernatant from this step was discarded and the pellet was suspended in of sucrose–phosphate–glutamate (SPG) buffer (200mM sucrose, 20mM NaH2PO4, 20mM Na2HPO4, 5mM L-Glutamic, dH2O [1pH 7.2]), aliquoted, and stored at −80°C (29).

Infection of trophoblast cells with C. trachomatis

Trophoblast cells (1×104) were seeded into wells of a 24-well plate and allowed to attach overnight. The next day, the cells were washed with PBS and infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5 - 2 in 200μl of antibiotic-free DMEM (Gibco) either by rocking at room temperature for 1 hour followed by resting for 1 hour, or in 1ml of SPG by spinning at 350g at 8-10°C for 40 minutes. This MOI was calculated, based on an assay performed using HeLa cells. The trophoblast cells were then washed with PBS to remove any unattached bacteria. Fresh serum-free OptiMEM (Gibco) was then added to the plates, and the cells were cultured at 37°C for 24 - 72 hours.

Inclusion Forming Unit (IFU) recovery

Trophoblasts were infected following as described using a 6 well plate, however, in this instance, the DMEM added post-infection contained 1μg/ml cyclohexamide. At 36 hours post-infection, EBs from the trophoblasts were collected as previously described for the stock preparations. Thus, the trophoblast cells were scraped, sonicated, centrifuged, and resuspended in 200μl of SPG. Dilutions of the trophoblast EBs were used immediately after collection, to infect HeLa cells. After rocking/resting the plates for 2 hours at room temperature, the media was replaced with DMEM/10% FBS supplemented with 1μg/ml cyclohexamide. The number of IFUs per trophoblast cell was calculated as follows: Using the poisson distribution, the mean number of IFU's infecting the HeLa cells was calculated using the percent uninfected cells (Po=e−m). We then multiplied (IFU/cell) by the number of cells plated/well to give us the number of IFUs/well. Based on the dilution of the stock and the volume used for infection, we determined the total number of IFUs in the stock. The following calculation was then performed: Total IFUs recovered divided by % infected trophoblast cells × total number of trophoblasts = Number of IFU recovered/infected cell.

Intracellular Staining and flow cytometry

Infection rates in both the trophoblast cells and the HeLa cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Post-infection, the cells were washed with PBS, detached with 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco), and collected with Staining Buffer (SB) (PBS, 1% FBS, and 0.1% Sodium azide [NaN3, Sigma]). The suspensions were transferred to a 5ml polystyrene round-bottom tube, snap cap (BD, Falcon) and centrifuged at 200g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The cell pellet was then suspended with SB and centrifuged two more times. After this, the cells were fixed in 1ml of 3.7% formaldehyde (Calbiochem) for 15-20 minutes at room temperature. The cells were then centrifuged and washed twice in 1ml of cold Perm/Wash buffer (#554723; BD Biosciences) and then incubated for 40 minutes on ice. After this, cells were centrifuged and then resuspended in 100ml of Perm/Wash and 3μl of a FITC-conjugated anti-Ct-LPS monoclonal antibody (mAb) was added, (#1649; ViroStat Inc, Portland, ME) and incubated for 25 minutes on ice in the dark. After adding 1ml of cold Perm/Wash buffer and centrifugation, the cells were washed with SB buffer and then resuspended in SB. For resuspending pellets, the tubes were gently flicked, medium added, and a quick touch with a vortexer on low speed. Cells were analyzed using the FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Data was acquired using CELLQUEST and analyzed using FlowJo software, respectively.

Immunofluorescent staining

Inclusion formation was monitored by light and immunofluorescent microscopy. Trophoblast cells (2×104) were grown on sterile (13mm) round cover slips placed in a 24 well plate and infected with Ct as already described. Post-infection, the cells were washed twice with PBS, and fixed/permeabilized with cold methanol for 20 minutes. After 2 washes with PBS, the coverslips with cells were removed from the wells and placed on a slide containing 5μl FITC-conjugated anti-Ct-LPS mAb (Virostat) and 5μl of 0.005% Evansblue dye. Slides were then incubated in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 30 minutes. The cover slips were then washed by tipping in sequential beakers containing, PBS, PBS, water and transferred to a slide with 8μl of antifade mounting solution (Invitrogen, Ca). Immunostained cells were then visualized with a Q-imaging 5.0 RTV camera mounted on a Nikon diaphot inverted microscope, and images were analyzed using QCapture software. A minimum of six different random fields of each slide were analyzed.

Cytokine studies

The effect of Ct infection on trophoblast cytokine/chemokine production was determined by multiplex technology. Following infection of trophoblast cells in a 24-well plate with Ct for 24 - 72 hours, the culture supernatants were collected and passed through a 13mm, 0.2μM pore size filter (Pall Corporation, East Hills, NY) to remove cell debris and any EBs. The supernatants were then stored at −80°C until analysis was performed. Supernatants were then analyzed for a full panel of cytokines and chemokines using the custom Bio-Plex Human Cytokine 19-Plex from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA) with detection and analysis using the Luminex 100 IS system (Upstate Biotechnology, Charlottesville, VA), as recently described (26). The 19 cytokines/chemokines analyzed were: IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-17, G-CSF, GM-CSF, GROα, IFNγ, MCP-1, MIP-1β, RANTES and TNFα.

Western blot analysis

For analysis of intracellular proteins, cells were lysed using 1% NP40 and 0.1% SDS in the presence of protease inhibitors (Roche). Protein concentrations were calculated by BCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Proteins were then diluted with gel loading buffer to 20μg and boiled for 5 minutes. Proteins were resolved under reducing conditions on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred onto PVDF paper (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA). Membranes were blocked at room temperature for 1 hour with 5% fat-free powdered milk (FFPM) in PBS/0.05% Tween-20 (PBS-T). Following three washes for 10 minutes each with PBS-T, membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the mouse anti-human NFκB p65 mAb, raised against the protein's N terminus (sc-8008, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Following this incubation, membranes were washed three times as before and then incubated at room temperature for 1 hour with the horse anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated to peroxidase (Vector Labs) in PBS-T/1% FFPM. Following three washes for 10 minutes each with PBS-T and three washes for 10 minutes each with distilled water, the peroxidase-conjugated antibody was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer). Membranes were then stripped and subsequently probed for C. trachomatis major outer membrane protein (MOMP) using the goat anti-MOMP antibody (Virostat). Images were recorded using the Gel Logic 100 (Kodak) and Kodak MI software.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). Statistical significance (p<0.05) was determined using either students's t-tests or, for multiple comparisons, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferonni's post-test or multiple regression analyses. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Results

C. trachomatis infects first trimester trophoblast cells

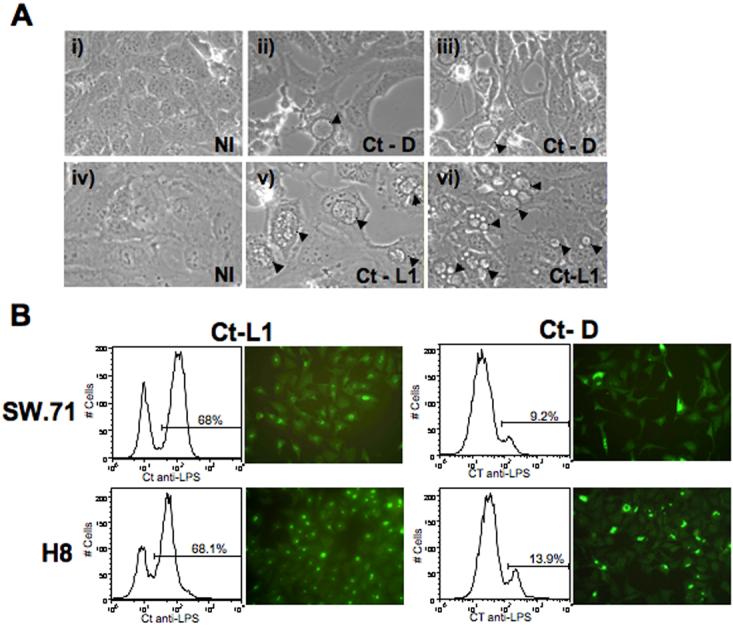

Recently, Azenabor et al., reported that Jar cells, a choriocarcinoma cell line, could be infected by C. trachomatis (30). Since Jar cells are derived from a choriocarcinoma, the first objective of our study was to determine whether non-malignant trophoblast cells could be infected with C. trachomatis. For this study we used two human first trimester trophoblast cells lines, H8 and Sw.71, as a model. We initially tested the ability of Ct, serovars D and L1, to infect trophoblast cells. As shown in Figure 1A, both serovar D (panels ii and iii) and serovar L1 (panels v and vi) infected the Sw.71 cell line, as evidenced by inclusion formation when compared to the uninfected cells (panels i and iv). The L1 serovar is highly invasive (31), and as a result we observed a much higher and faster rate of infection. Indeed, multiple inclusions could be seen in the cells as early as 24 hours post-infection, while inclusions were not seen in the cells infected with serovar D (Ct-D) until 36 - 48 hours post-infection. Staining of the infected trophoblast cells with a Ct specific anti-LPS antibody either by flow cytometry or immunofluorescence confirmed that the inclusions observed in the trophoblast cells contained Chlamydia (Figure 1B). Furthermore, the number of Chlamydia positive trophoblast cells correlated using the two methods. Using immunofluorecent microscopy we found that with the serovar L1 69% (356/513) of H8 cells and 75.5% (385/570) of Sw.71 cells were infected. Using the serovar D, 20.5% (97/472) of H8 cells and 21.2% (68/322) of Sw.71 cells were infected. These levels of infection were similar to that determined using flow cytometry (Figure 1B). Since serovar D more commonly infects the female genital tract (13), we used this serovar for all subsequent studies.

Figure 1.

Inclusion formation and infection rates in trophoblast cells infected with C. trachomatis. (A) Trophoblast cells (Sw.71) were exposed to either No infection (NI), Ct serovar D (Ct-D) or Ct serovar L1 (Ct-L1) at a MOI of 1, by rocking/resting at room temperature for 2 hour. Inclusion formation was evaluated by light microscopy at 24 and 36 hours post-infection for Ct-L1 and Ct-D, respectively. Inclusions are highlighted by arrow heads (Mag. ×40). (B) After 36 hours of infection with or without Ct-L1 or Ct-D, inclusion formation in the Sw.71 and H8 cells was evaluated by by staining cells intracellularly with a FITC-conjugated mouse anti-Ct LPS mAb. Infection rates were then determined by both immmunofluorescent microscopy and flow cytometry. The flow cytometry histograms show two distinct populations: the left hand peak being the uninfected cells, and the right hand peak with the marker representing the infected trophoblast population.

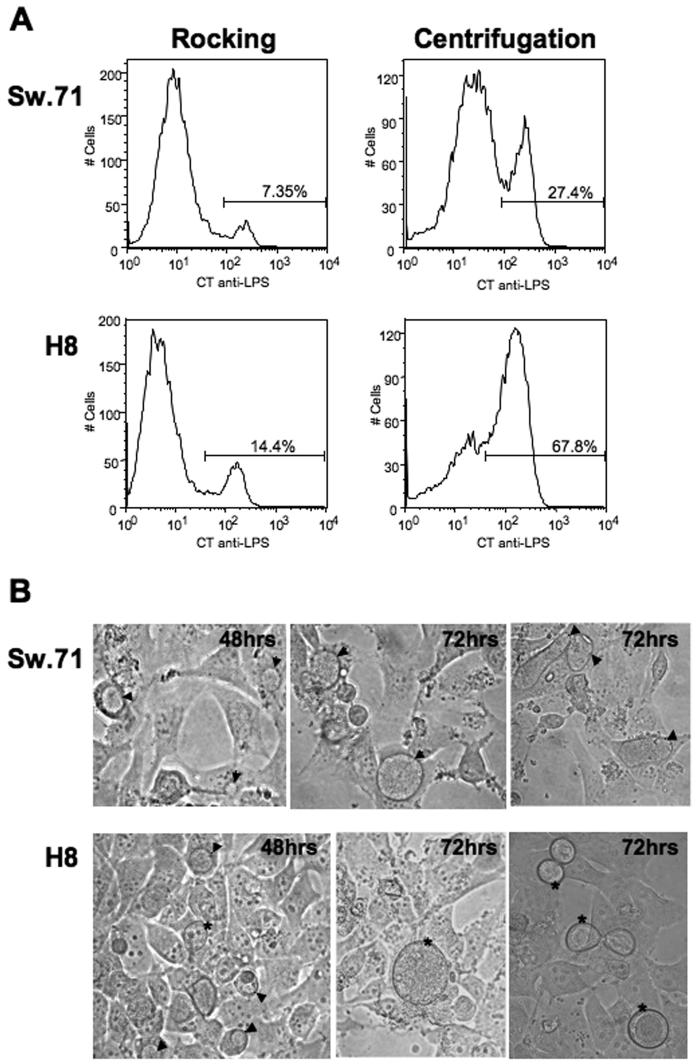

Having established that first trimester trophoblast cells could be infected by Ct, we next optimized the infection procedure. As shown in Figure 2A, a higher rate of infection of both the H8 and Sw.71 cells could be achieved when the cells were centrifuged with the bacteria, when compared with the cells infected with the same MOI by rocking. Therefore, this centrifugation technique was used for all subsequent infections. Interestingly, there was a difference in the Ct infection between the two cell lines. At 48 hours post-infection, medium sized inclusions could be seen within the Sw.71 cells and H8 cells. By 72 hours post-infection the inclusions in Sw.71 cells had increased in size and there was a little cell debris, probably due to lysis of the cells by the infection (Figure 2B). However, in the H8 cells at 72 hours post-infection, the majority of inclusions appeared to have been extruded, as previously reported (14), and there was little, if any, cellular debris (Figure 2B). These extruded inclusions had no nucleus and had a similar morphology to the cytoplasmic inclusions.

Figure 2.

Infection rates of trophoblast cells infected with C. trachomatis by different techniques. (A) H8 and Sw.71 cells were infected with Ct (serovar D) at an MOI of 1 by either rocking or by centrifugation. After 36 hours, the cells were collected and stained intracellularly with a FITC-conjugated mouse anti-Ct LPS mAb. Centrifugation resulted in a higher rate of infection in both cell lines (B) H8 and Sw.71 cells were infected with or without Ct (serovar D) at an MOI of 1 by centrifugation. After 48 and 72 hours inclusion formation was visualized by light microscopy. Inclusions contained within the cells are highlighted by arrow heads, while extruded inclusions are highlighted by asterisks (Mag. ×40).

Chlamydia-infected trophoblast cells produce viable EBs

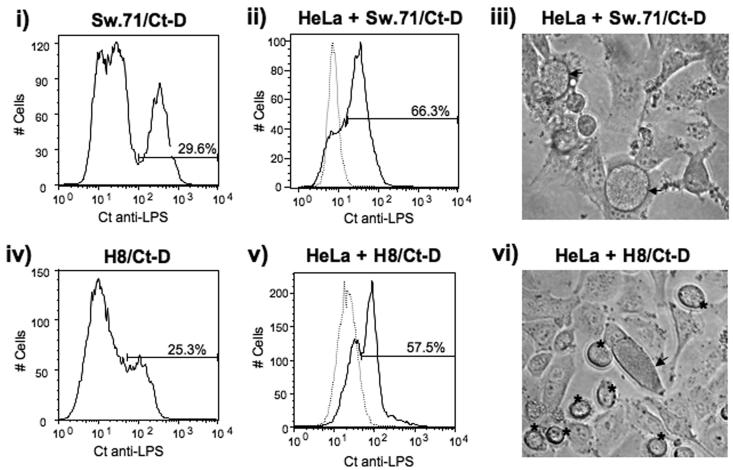

We next sought to determine whether the Chlamydia life cycle had been completed within the infected trophoblast cells. EBs were prepared using our standard protocol from infected trophoblast cells. Immediately after collection, the stock was titered on uninfected HeLa cells and the rate of infection determined. At 36 hours post-infection, 29.6 % of the Sw.71 were infected by Ct (Figure 3, i), and the EBs from these were able to infect 66.3% of HeLa cells (Figure 3, ii). At 36 hours post-infection, 25.3% of the H8 cells were infected by Ct (Figure 3, iv), and we were able to infect 57.5% of the HeLa cells (Figure 3, v). We calculated that approximately 700 IFUs were derived per infected cell from either cell line, which possibly corresponds to an average of 2 inclusion bodies per infected trophoblast cell. Interestingly when we assayed the HeLa cells for infectivity, we noted inclusions induced by the H8-derived EBs, that appeared to be extruded by the HeLa cells (Figure 3, vi). However, we did not observe these independent inclusions when infecting the HeLa cells with EBs prepared from the Sw.71 cells (Figure 3, iii).

Figure 3.

Chlamydia-infected trophoblast cells produce viable EBs. H8 and Sw.71 cells were infected with Ct (serovar D) at an MOI of 1 by centrifugation. After 36 hours, the cells were collected and stained intracellularly with a FITC-conjugated mouse anti-Ct LPS mAb. The infection levels were then determined by flow cytometry (i & iv). In parallel, lysates were prepared from Ct-infected H8 and Sw.71 cells and these were then immediately applied to a culture of uninfected HeLa cells. After 48 hours, the HeLa cells exposed to infected Sw.71 or H8 lysates were collected and the infection levels determined by flow cytometry. Histograms (ii & v) show the levels of HeLa cell Ct infection (solid line), when compared to the uninfected HeLa cells (dotted line). The HeLa cells exposed to infected Sw.71 or H8 lysates were also evaluated for inclusion formation by light microcopy (iii & vi). Inclusions contained within the cells are highlighted by arrow heads, while extruded inclusions are highlighted by asterisks (Mag. ×40) (iii & iv).

C. trachomatis infection of trophoblast results in a differential cytokine/chemokine profile

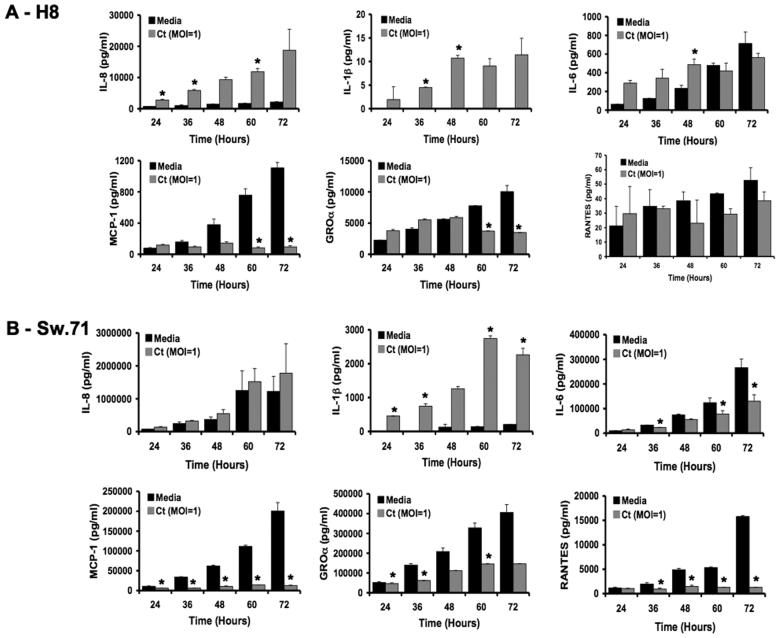

Infection of various human cells with Chlamydia can lead to the production of chemokines and cytokines, such as IL6, IL-8 (CXCL8), IL-1β and IL-18 (32-35). Thus, our objective was to determine whether the same would be true in trophoblast cells. In addition, first trimester trophoblast cells constitutively secrete specific chemokines and cytokines which could also be affected by Chlamydia infection (22, 26). We, therefore, evaluated multiple cytokines and chemokines secreted by the trophoblast cells post-infection by performing a time course from 24 to 72 hours, and analyzing the cell-free culture supernatants using multiplex analysis. Out of the 19 factors tested, the levels of 6 cytokines/chemokines were significantly and consistently altered. As shown in Figure 4A and B, IL-1β was strongly induced in both the H8 and Sw.71 cell lines following a Ct infection (MOI of 1), when compared to the uninfected cells (Media) (p<0.05). H8 secretion of IL-8 (CXCL8), was also strongly upregulated in a time-dependent manner following Ct infection, when compared to the media-treated cells (p<0.05); but this was not the case for the Sw.71 cells. One of the most interesting and striking findings was that MCP-1 (CCL2) was strongly suppressed in both cell lines (p<0.05) following Ct infection. The chemokines, GROα (CXCL1) and RANTES (CCL5) were also consistently decreased in the Sw.71 cells, whereas in the H8 cells, we observed either some decrease or no change. In contrast to other studies, IL-6 was not strongly induced but rather showed little change in the H8 cells, or decreased production in the Sw.7 cells (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cytokine profile of trophoblast cells infected with C. trachomatis. First trimester trophoblast cells were treated with either media, or infected with Ct serovar D at a MOI of 1 by centrifugation. After 24, 36, 48, 60 and 72 hours, cell-free/EB-free supernatants were collected and evaluated for cytokine/chemokines by multiplex analysis. Barcharts show the levels of IL-8, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, GROα and RANTES secreted by (A) H8 cells and (B) Sw.71 cells, after treatment with either media or Ct (n=3; *p<0.05). A representative experiment of three is presented.

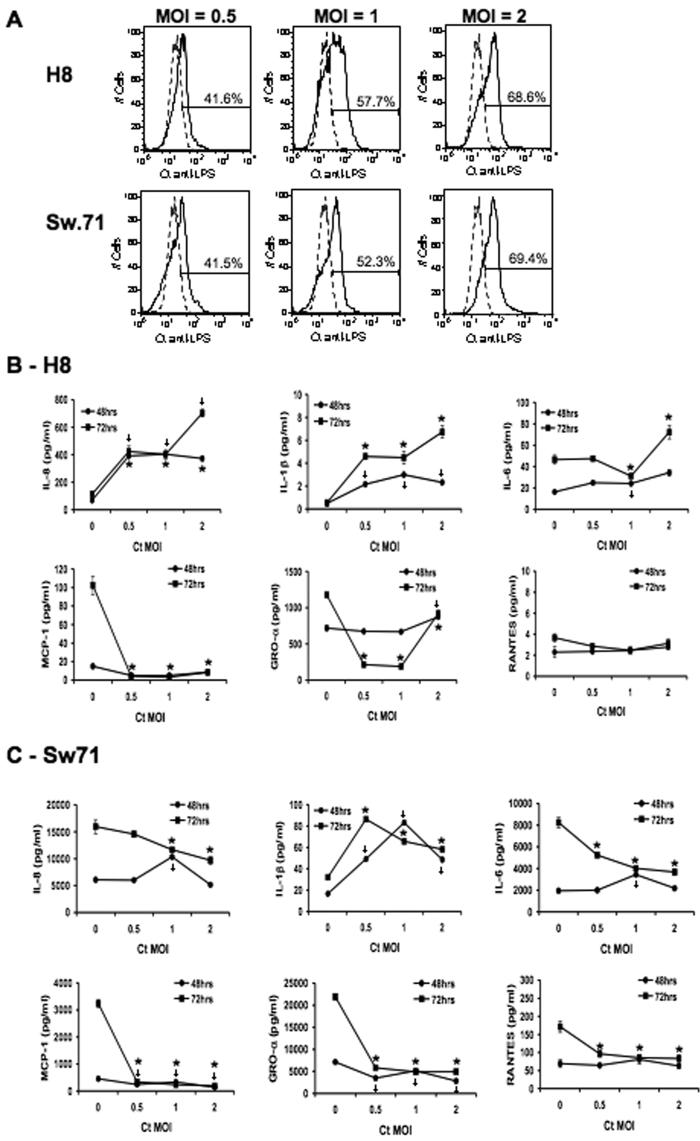

These observations were next validated by performing a dose-response. Thus, H8 and Sw.71 cells were infected with Ct at 3 different MOIs, and the levels of infection as well as the secreted cytokine/chemokine response was evaluated. As shown in Figure 5A, the infection rates of both cell lines increased in a dose-dependent manner. When the cytokine/chemokine response was analyzed, the same patterns of response for IL-8, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, GROα and RANTES were observed in the two cell lines (Figure 6B & C). The only difference was that in the H8 cells, IL-6 secretion was increased at the high MOI of 2 (Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

C. trachomatis modulates trophoblast cytokine/chemokine production in a dose-dependent manner. Trophoblast cells (H8 and Sw.71) were infected with Ct at a MOI of 0 (uninfected), 0.5, 1 or 2. (A) After 36 hours infection levels were determined by flow cytometry. Histograms show the percentage of infected cells (solid line) when compared to the uninfected cells (dotted line). After 48 and 72 hours, cell-free/EB-free supernatants were collected and evaluated for cytokines/chemokines by multiplex analysis. (B & C) Line charts show the levels of IL-8, IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, GROα and RANTES secreted by (B) H8 cells and (C) Sw.71 cells, after infection with or without Ct (n=3; *p<0.05). A representative experiment of three is presented.

Figure 6.

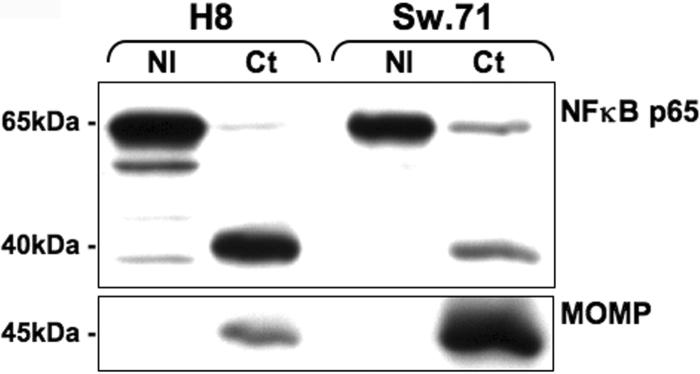

Infection of trophoblast cells with C. trachomatis reduces NFκB p65 expression levels. Trophoblast cells (H8 and Sw.71) were either non-infected (NI), or infected with C. trachomatis (serovar D) at a MOI of 1. After 48 hours, cell lysates were prepared and Western blot analysis for NFκB p65 (65kDa) and Ct MOMP (45kDa) was performed.

C. trachomatis infection of trophoblast results in NFκB p65 cleavage

Having established that Ct infection of trophoblast cells can differentially modulate their cytokine and chemokine production, we next sought to determine the mechanisms involved. The NFκB pathway is important for constitutive trophoblast cytokine/chemokine production (36), and is involved in trophoblast cell responses to bacterial components (37). Moreover, a recent study reported that Chlamydia infection can lead to the degradation of the NFκB p65 subunit by secreting a protease encoded by CT441 into the host cytosol. In this study, this protease resulted in cleavage of NFκB p65 into two subunits and the p40 subunit could be detected with an antibody recognizing the N terminus of the p65 protein (17). Therefore, we examined the effects of Ct infection on the expression levels of the NFκB p65 subunit and its p40 cleavage product. The H8 and Sw.71 cells were either non-infected (NI) or infected with Ct at a MOI of 1. After 48 hours, cells were lysed for protein and NFκB p65 expression was analyzed by Western blot. As shown in Figure 6 following Ct infection, we observed a decrease in the levels of the NFκB p65 protein, and the appearance of a p40 protein. Ct infection in these cells was confirmed by the detection of the Ct Major outer membrane protein (MOMP), which was absent in the non-infected cells.

Discussion

Intrauterine infections can pose a threat to pregnancy by gaining access to the placenta and fetus; and clinical studies have strongly linked bacterial infections with preterm labor (19). A key observation in infection-associated abnormal pregnancies is excessive inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface (38). While C. trachomatis can infect the placenta and decidua (9, 10, 12), little is known about its effects on trophoblast cell immune function. The findings of this current study indicate that the trophoblast is a target for C. trachomatis; and Chlamydia infection results in modulation of the cell's cytokine/chemokine response. Specifically, our results demonstrate that for both trophoblast cells used in this study, Ct infection led to elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β; while the cell's constitutive secretion of the chemokine, MCP-1, is inhibited. Furthermore, Ct infection of trophoblast cells resulted in the cleavage of NFκB p65.

Three previous studies have investigated Ct infection of the trophoblast in vitro. Banks et al., found that C. trachomatis could infect murine trophoblast cells (39), and two subsequent studies using the choriocarcinoma cell lines, Jar and BeWo, have demonstrated infection by Chlamydophila abortus and C. trachomatis (30, 40). In one of these studies, C. trachomatis infection of Jar cells was shown to alter their production of hormones (30). The other study, which used the BeWo cell line, reported a lack of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) expression by gamma interferon when the cells were infected by Chlamydophila abortus.

For our studies, we used two different human trophoblast cell lines. The first cell line, H8, was established by transformation with the SV40 large T antigen (24); and the other cell line, Sw.71, was immortalized using retroviral transduction with the telomerase gene (23, 25). We found that C. trachomatis infected both trophoblast cell lines, formed inclusions, and generated large numbers of infectious EBs per cell. Interestingly, we observed some differences between the two cells lines. Infectious EB particles can be released from cells either by lysis or by extrusion of the inclusion (14). In the Sw.71 cells, following completion of the Chlamydia's life cycle, the infectious EBs appeared to be released through lysis, while in the H8 cells, this appeared to primarily occur through extrusion of the inclusion. Moreover, we found that infected HeLa cells showed extruded inclusions generated from the H8-derived EBs, while this was not the case with the Sw.71-derived EBs. This observation suggests that the H8 cells may have the capacity to modify the Ct EBs.

C. trachomatis infection of the two trophoblast cell lines used in this study did not appear to result in an induction of apoptosis. While some cell lysis in the Sw.71 cells was observed, this did not occur until 72 hours post-infection, and it was not extensive. Moreover, little, if any, cell lysis was observed in the infected H8 cells, most likely because of inclusion extrusion. A recent study which reported that recombinant Chlamydia heat shock protein 60 (HSP60) induces rapid trophoblast apoptosis within 4 hours of exposure (41). Using a cell viability assay, we evaluated the effects of UV-inactivated Chlamydia on trophoblast cells and found no induction of cell death (unpublished results), suggesting that in the context of the whole bacterium, the HSP60 protein does not induce trophoblast cell death and apoptosis. This is consistent with the general finding that Ct secretes a virulence factor that blocks apoptosis (42-44).

Production of chemokines and cytokines by the trophoblast is believed to be important for the maintenance of a normal pregnancy by recruiting immune cells to the maternal-fetal interface, and influencing their activation status (22, 23). We previously showed that first trimester trophoblast cells constitutively produce chemoattractants, such as IL-8, MCP-1 and GROα (22, 23, 26). For instance, MCP-1 and GROα are chemokines involved in recruitment of monocytes/macrophages into tissues. The presence of non-inflammatory macrophages at the maternal-fetal interface is critical for pregnancy (45, 46). These innate immune cells are thought to play an active role in promoting trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodeling during normal pregnancy (21, 23, 47). However, alterations in the trophoblast-macrophage crosstalk may arise upon the trophoblast sensing and responding to microbial products through pattern recognition receptors, and this may in turn influence pregnancy outcome (21).

In this study we found that Ct infection of both trophoblast cell lines results in the downregulation of MCP-1 and GROα secretion. This altered chemokine production by the trophoblast could prevent further migration of macrophages into the maternal-fetal interface. In parallel, any trophoblast-derived inflammatory factors may inappropriately activate the resident macrophages, already present at the maternal-fetal interface. Furthermore, these resident macrophages may themselves become infected by Ct to generate an inflammatory response. Since parturition is an inflammatory process that is associated with macrophage activation at the maternal-fetal interface (48-50), such altered macrophage distribution and activation status created by a trophoblast Ct infection may lead to adverse pregnancy outcome, such as preterm labor (51).

In contrast to the reduced MCP-1 and GROα production, we found a concomitant induction in trophoblast secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, following Ct infection in both cell lines. Previous studies have shown that production of IL-1β is induced by Ct in epithelial cells and immune cells; and is dependent upon activation of caspase-1, which mediates the processing of pro-IL-1β into its active form (32, 52). Activation of caspase-1 also leads to processing of IL-18 (53); and the secretion of IL-18 by human epithelial cell lines infected with C. trachomatis correlates with casapse-1 activation (33). Furthermore, in vivo, chlamydial infection-induced inflammatory damage in urogenital infections of the mouse is mediated, in part, by activation of caspase-1 (54). Thus, production of IL-1β, through caspase-1 activation, by Ct infected trophoblast cells may contribute to the pathology during pregnancy and this may in turn compromise pregnancy outcome.

The production of IL-1β by the trophoblast after chlamydial infection supports the possibility that Ct infection activates the inflammasome, a multi-protein complex consisting of the adaptor protein, ASC (apoptosis-associated specklike protein containing a caspase activation recruitment domain) (55). ASC can be activated by Nod-like receptor (NLR) family, which are cytoplasmic-based pattern recognition receptors (56). Indeed, NLRs, such as NALP1, NALP3 and Ipaf, upon ligand binding can lead to activation of caspase-1, and subsequent processing of IL-1β and IL-18 (57, 58). Another set of NLRs, Nod1 and Nod2, recognize bacterial products and activate the NFκB and MAPK kinase pathways leading to production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (59). Nod1 and Nod2 are expressed in trophoblast cells and in response to their specific agonists, modulate trophoblast cytokine and chemokine production (26) (Mulla et al., manuscript under review). Nod1 has been reported to be activated by C. trachomatis (60), and both Nod1 and Nod2 have been implicated in responses towards C. pneumoniae (61). Interestingly, through their CARD domains, Nod1 and Nod2, may also recruit and activate caspase-1, leading to the processing of inactive IL-1β into its active form (62, 63). Therefore, it is possible that activation of one of these receptors may lead to the upregulation of IL-1β secretion in the trophoblast. We are in the process of determining which NLR may be used to activate caspase-1 and the production of IL-1β following Ct infection of trophoblast cells.

It is interesting to note that while the Sw.71 cells express both Nod1 and Nod2, the H8 cells only express Nod1 (26). It is, therefore, possible that any differential effects observed may be a reflection of the receptor expression profile in the two trophoblast cell lines. Indeed, we found that following Ct infection IL-6 and RANTES production was reduced in the Sw.71 cells, but not in the H8 cells. In contrast, a strong upregulation of IL-8 secretion was seen in the H8 cells, but not the Sw.71 cells. Should augmentation of IL-8 production by the trophoblast occur in response to a Ct infection, this is likely to result in a neutrophilic infiltrate into the maternal-fetal interface, which may have detrimental effects on the pregnancy. Indeed, an influx of neutrophils into the maternal-fetal interface is associated with adverse pregnancy outcome, such as preterm labor (64, 65); and we have previously reported that trophoblast cells secreting high levels of IL-8 can actively recruit neutrophils (22). Thus, in the presence of a Ct infection the increased IL-8 production by the trophoblast may lead to increased neutrophils at the maternal-fetal interface and this may have a negative impact on pregnancy outcome.

In other cell types, Ct infection upregulates IL-8 production via the MAPK and NFκB pathways (32, 34, 66, 67). A study by O'Connell et al., demonstrated in epithelial cells, that IL-8 production triggered by Ct was mediated by TLR-2. However, we have previously reported that activation of TLR-2 in first trimester trophoblast cells triggers apoptosis, and shuts down cytokine production in these cells (27, 68). Therefore, in the trophoblast, the TLRs may not be the primary mode of chlamydial recognition. This, however, still does not rule out a role for TLR-2 in trophoblast responses to Chlamydia, since the active infection may be able to block the pro-apoptotic effects of this receptor (44, 69, 70), and this may result in recovery of the TLR-2 mediated cytokine response (37).

While the upregulation of IL-1β and IL-8 secretion in response to a Ct infection is likely to be the result of trophoblast pattern recognition responses, we questioned how the production of the chemokines, such as MCP-1, GROα and RANTES could be simultaneously reduced. MCP-1, RANTES and GROα are known to be regulated by the NFκB pathway and STAT3 (71-73). Members of the Rel family of transactivators, specifically p65 (RelA), as well as transcription factors AP1 and SP1 bind to the MCP-1 upstream promoter (74). Therefore, the suppression of MCP-1 secretion that we see in both trophoblast cell lines following Ct infection, may be occurring through degradation of the NFκB p65 protein. Indeed, in our current study, we found that Ct infection of the trophoblast resulted in the cleavage of NFκB p65, as previously reported, which could interfere with the signaling pathway (17). This suggests that some of the chemokine inhibitory effects observed in the presence of a Ct infection, might be a result of the degradation of this NFκB protein. Alternatively, if the NLR receptor, NALP3, is activated by Chlamydia, this may also contribute to suppression of GROα, RANTES and MCP-1 induction, as NALP3 has been shown to inhibit the NFκB pathway (75). However, IL-8 production can also be regulated by NFκB p65 (76, 77). Since Ct infection of H8 trophoblast cells increased IL-8 production, this may indicate that IL-8 regulation in the trophoblast by Chlamydia may either be at the translational or secretory level. Alternatively, MCP-1/RANTES/GROα and IL-8 production in the trophoblast may be regulated by distinct transcription factors. Indeed, in epithelial cells, in addition to AP-1 and members of the NFκB pathway, nuclear factor IL-6 (NFIL6)/CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBP) was found to be involved in IL-8 transcription during C. trachomatis infection (66). In addition, a recent study showed that Ct infection of epithelial cells induced IL-8 production via the MAPK pathway (67).

In summary, we have demonstrated that a C. trachomatis infection of first trimester trophoblast cells results in differential modulation of the cell's cytokine and chemokine production. The findings of this study suggest that upregulation of chemokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines by trophoblast likely result from activation of innate immune receptors in an attempt to control the infection; in contrast, the downregulation of certain chemokines normally secreted by the trophoblast cell suggests that Ct infection can modify the trophoblast's immune response. These findings support our hypothesis that the effect of a Chlamydia infection on secretion of chemokines/cytokines by the trophoblast cells is likely to be a dynamic interaction of activation of innate immune receptors expressed by the trophoblast and virulence factors secreted into the trophoblast cytoplasma by the bacteria. Furthermore, such altered trophoblast responses in the presence of a Chlamydia infection may have a profound effect on the immune cell distribution and activation status at the maternal-fetal interface, which may in turn impact pregnancy outcome, resulting in complications, such as preterm labor.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Paulomi Aldo for her assistance with the Bio-plex assay.

Abbreviations

- Ct

Chlamydia trachomatis

- EB

Elementary body

- IFU

Inclusion forming unit

- MOMP

Major outer membrane protein

- MOI

Multiplicity of infection

- NI

Non-infected

- NLR

Nod-like receptor

- RB

Reticuloid body

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

Footnotes

This study was supported, in part, by grants RO1049571 (PBK) and RO1HD049446 (VMA) from the NIH.

References

- 1.Lee BN, Hammill H, Popek EJ, Cron S, Kozinetz C, Paul M, Shearer WT, Reuben JM. Production of interferons and beta-chemokines by placental trophoblasts of HIV-1-infected women. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2001;9:95–104. doi: 10.1155/S1064744901000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Amortegui AJ, Heine RP, Landers DV, Sweet RL. Lower genital tract infection and endometritis: insight into subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:456–463. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Voorhis WC, Barrett LK, Sweeney YT, Kuo CC, Patton DL. Repeated Chlamydia trachomatis infection of Macaca nemestrina fallopian tubes produces a Th1-like cytokine response associated with fibrosis and scarring. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2175–2182. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2175-2182.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hossain A, Arif M, Ramia S, Bakir TF. Chlamydia trachomatis as a cause of abortion. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1990;34:53–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain A, Nag VL, Goel MM, Chandrawati, Chaturvedi UC. Adverse foetal outcome in specific IgM positive Chlamydia trachomatis infection in pregnancy. Indian J Med Res. 1991;94:420–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Dadelszen P, Magee LA. Could an infectious trigger explain the differential maternal response to the shared placental pathology of preeclampsia and normotensive intrauterine growth restriction? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:642–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baud D, Regan L, Greub G. Emerging role of Chlamydia and Chlamydia-like organisms in adverse pregnancy outcomes. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:70–76. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f3e6a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manavi K. A review on infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;20:941–951. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong ZW, Li Y, Zhang LY, Liu RM. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis intrauterine infection using polymerase chain reaction on chorionic villi. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1998;61:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(98)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baboonian C, Smith DA, Shapland D, Arno G, Zal B, Akiyu J, Kaski JC. Placental infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae and intrauterine growth restriction. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:165–169. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00321-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magon T, Kluz S, Chrusciel A, Obrzut B, Skret A. The PCR assessed prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis in aborted tissues. Med Wieku Rozwoj. 2005;9:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonagh S, Maidji E, Ma W, Chang HT, Fisher S, Pereira L. Viral and bacterial pathogens at the maternal-fetal interface. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:826–834. doi: 10.1086/422330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beagley KW, Timms P. Chlamydia trachomatis infection: incidence, health costs and prospects for vaccine development. J Reprod Immunol. 2000;48:47–68. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(00)00069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hybiske K, Stephens RS. Mechanisms of host cell exit by the intracellular bacterium Chlamydia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11430–11435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703218104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fields KA, Mead DJ, Dooley CA, Hackstadt T. Chlamydia trachomatis type III secretion: evidence for a functional apparatus during early-cycle development. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:671–683. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scidmore MA, Fischer ER, Hackstadt T. Restricted fusion of Chlamydia trachomatis vesicles with endocytic compartments during the initial stages of infection. Infect Immun. 2003;71:973–984. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.973-984.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lad SP, Li J, da Silva Correia J, Pan Q, Gadwal S, Ulevitch RJ, Li E. Cleavage of p65/RelA of the NF-kappaB pathway by Chlamydia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2933–2938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608393104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhong G, Fan P, Ji H, Dong F, Huang Y. Identification of a chlamydial protease-like activity factor responsible for the degradation of host transcription factors. J Exp Med. 2001;193:935–942. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goncalves LF, Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R. Intrauterine infection and prematurity. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002;8:3–13. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abrahams VM, Mor G. Toll-like receptors and their role in the trophoblast. Placenta. 2005;26:540–547. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mor G, Romero R, Aldo PB, Abrahams VM. Is the trophoblast an immune regulator? The role of Toll-like receptors during pregnancy. Crit Rev Immunol. 2005;25:375–388. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v25.i5.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abrahams VM, Visintin I, Aldo PB, Guller S, Romero R, Mor G. A role for TLRs in the regulation of immune cell migration by first trimester trophoblast cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:8096–8104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fest S, Aldo PB, Abrahams VM, Visintin I, Alvero A, Chen R, Chavez SL, Romero R, Mor G. Trophoblast-macrophage interactions: a regulatory network for the protection of pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;57:55–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2006.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham CH, Hawley TS, Hawley RG, MacDougall JR, Kerbel RS, Khoo N, Lala PK. Establishment and characterization of first trimester human trophoblast cells with extended lifespan. Exp Cell Res. 1993;206:204–211. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aplin JD, Straszewski-Chavez SL, Kalionis B, Dunk C, Morrish D, Forbes K, Baczyk D, Rote N, Malassine A, Knofler M. Trophoblast differentiation: progenitor cells, fusion and migration -- a workshop report. Placenta. 2006;27(Suppl A):S141–143. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costello MJ, Joyce SK, Abrahams VM. NOD protein expression and function in first trimester trophoblast cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;57:67–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2006.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abrahams VM, Bole-Aldo P, Kim YM, Straszewski-Chavez SL, Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Mor G. Divergent trophoblast responses to bacterial products mediated by TLRs. J Immunol. 2004;173:4286–4296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leonhardt RM, Lee SJ, Kavathas PB, Cresswell P. Severe tryptophan starvation blocks onset of conventional persistence and reduces reactivation of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5105–5117. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00668-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caldwell HD, Kromhout J, Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1981;31:1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azenabor AA, Kennedy P, Balistreri S. Chlamydia trachomatis infection of human trophoblast alters estrogen and progesterone biosynthesis: an insight into role of infection in pregnancy sequelae. Int J Med Sci. 2007;4:223–231. doi: 10.7150/ijms.4.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rampf J, Essig A, Hinrichs R, Merkel M, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Sunderkotter C. Lymphogranuloma venereum - a rare cause of genital ulcers in central Europe. Dermatology. 2004;209:230–232. doi: 10.1159/000079896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gervassi A, Alderson MR, Suchland R, Maisonneuve JF, Grabstein KH, Probst P. Differential regulation of inflammatory cytokine secretion by human dendritic cells upon Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun. 2004;72:7231–7239. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7231-7239.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu H, Shen C, Brunham RC. Chlamydia trachomatis infection of epithelial cells induces the activation of caspase-1 and release of mature IL-18. J Immunol. 2000;165:1463–1469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasmussen SJ, Eckmann L, Quayle AJ, Shen L, Zhang YX, Anderson DJ, Fierer J, Stephens RS, Kagnoff MF. Secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by epithelial cells in response to Chlamydia infection suggests a central role for epithelial cells in chlamydial pathogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:77–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI119136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Westreenen M, Pronk A, Diepersloot RJ, de Groot PG, Leguit P. Chlamydia trachomatis infection of human mesothelial cells alters proinflammatory, procoagulant, and fibrinolytic responses. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2352–2355. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2352-2355.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosen T, Krikun G, Ma Y, Wang EY, Lockwood CJ, Guller S. Chronic antagonism of nuclear factor-kappaB activity in cytotrophoblasts by dexamethasone: a potential mechanism for antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids in human placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3647–3652. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.10.5151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abrahams VM, Aldo PB, Murphy SP, Visintin I, Koga K, Wilson G, Romero R, Sharma S, Mor G. TLR6 modulates first trimester trophoblast responses to peptidoglycan. J Immunol. 2008;180:6035–6043. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elovitz MA, Mrinalini C. Animal models of preterm birth. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15:479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banks J, Glass R, Spindle AI, Schachter J. Chlamydia trachomatis infection of mouse trophoblasts. Infect Immun. 1982;38:368–370. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.1.368-370.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Entrican G, Wattegedera S, Chui M, Oemar L, Rocchi M, McInnes C. Gamma interferon fails to induce expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and does not control the growth of Chlamydophila abortus in BeWo trophoblast cells. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2690–2693. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2690-2693.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Equils O, Lu D, Gatter M, Witkin SS, Bertolotto C, Arditi M, McGregor JA, Simmons CF, Hobel CJ. Chlamydia heat shock protein 60 induces trophoblast apoptosis through TLR4. J Immunol. 2006;177:1257–1263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao Y, Zhong Y, Greene W, Dong F, Zhong G. Chlamydia trachomatis infection inhibits both Bax and Bak activation induced by staurosporine. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5470–5474. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5470-5474.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ying S, Seiffert BM, Hacker G, Fischer SF. Broad degradation of proapoptotic proteins with the conserved Bcl-2 homology domain 3 during infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1399–1403. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1399-1403.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong F, Pirbhai M, Xiao Y, Zhong Y, Wu Y, Zhong G. Degradation of the proapoptotic proteins Bik, Puma, and Bim with Bcl-2 domain 3 homology in Chlamydia trachomatis-infected cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1861–1864. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1861-1864.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gustafsson C, Mjosberg J, Matussek A, Geffers R, Matthiesen L, Berg G, Sharma S, Buer J, Ernerudh J. Gene expression profiling of human decidual macrophages: evidence for immunosuppressive phenotype. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heikkinen J, Mottonen M, Komi J, Alanen A, Lassila O. Phenotypic characterization of human decidual macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;131:498–505. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abrahams VM, Kim YM, Straszewski SL, Romero R, Mor G. Macrophages and apoptotic cell clearance during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;51:275–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osman I, Young A, Ledingham MA, Thomson AJ, Jordan F, Greer IA, Norman JE. Leukocyte density and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human fetal membranes, decidua, cervix and myometrium before and during labour at term. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:41–45. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh U, Nicholson G, Urban BC, Sargent IL, Kishore U, Bernal AL. Immunological properties of human decidual macrophages--a possible role in intrauterine immunity. Reproduction. 2005;129:631–637. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomson AJ, Telfer JF, Young A, Campbell S, Stewart CJ, Cameron IT, Greer IA, Norman JE. Leukocytes infiltrate the myometrium during human parturition: further evidence that labour is an inflammatory process. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:229–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gomez R, Romero R, Edwin SS, David C. Pathogenesis of preterm labor and preterm premature rupture of membranes associated with intraamniotic infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1997;11:135–176. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng W, Shivshankar P, Li Z, Chen L, Yeh IT, Zhong G. Caspase-1 contributes to Chlamydia trachomatis-induced upper urogenital tract inflammatory pathologies without affecting the course of infection. Infect Immun. 2008;76:515–522. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01064-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akita K, Ohtsuki T, Nukada Y, Tanimoto T, Namba M, Okura T, Takakura-Yamamoto R, Torigoe K, Gu Y, Su MS, Fujii M, Satoh-Itoh M, Yamamoto K, Kohno K, Ikeda M, Kurimoto M. Involvement of caspase-1 and caspase-3 in the production and processing of mature human interleukin 18 in monocytic THP.1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26595–26603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheng W, Shivshankar P, Li Z, Chen L, Yeh IT, Zhong G. Caspase 1 contributes to Chlamydia trachomatis-induced upper urogenital tract inflammatory pathologies without affecting the infection course. Infect Immun. 2007 doi: 10.1128/IAI.01064-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taniguchi S, Sagara J. Regulatory molecules involved in inflammasome formation with special reference to a key mediator protein, ASC. Semin Immunopathol. 2007;29:231–238. doi: 10.1007/s00281-007-0082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sirard JC, Vignal C, Dessein R, Chamaillard M. Nod-like receptors: cytosolic watchdogs for immunity against pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e152. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferrero-Miliani L, Nielsen OH, Andersen PS, Girardin SE. Chronic inflammation: importance of NOD2 and NALP3 in interleukin-1beta generation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:227–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murray PJ. NOD proteins: an intracellular pathogen-recognition system or signal transduction modifiers? Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Welter-Stahl L, Ojcius DM, Viala J, Girardin S, Liu W, Delarbre C, Philpott D, Kelly KA, Darville T. Stimulation of the cytosolic receptor for peptidoglycan, Nod1, by infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or Chlamydia muridarum. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1047–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Opitz B, Forster S, Hocke AC, Maass M, Schmeck B, Hippenstiel S, Suttorp N, Krull M. Nod1-mediated endothelial cell activation by Chlamydophila pneumoniae. Circ Res. 2005;96:319–326. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000155721.83594.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoo NJ, Park WS, Kim SY, Reed JC, Son SG, Lee JY, Lee SH. Nod1, a CARD protein, enhances pro-interleukin-1beta processing through the interaction with pro-caspase-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;299:652–658. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02714-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Netea MG, Azam T, Ferwerda G, Girardin SE, Walsh M, Park JS, Abraham E, Kim JM, Yoon DY, Dinarello CA, Kim SH. IL-32 synergizes with nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD) 1 and NOD2 ligands for IL-1beta and IL-6 production through a caspase 1-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16309–16314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508237102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Andrews WW, Goldenberg RL, Faye-Petersen O, Cliver S, Goepfert AR, Hauth JC. The Alabama Preterm Birth study: polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cell placental infiltrations, other markers of inflammation, and outcomes in 23- to 32-week preterm newborn infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:803–808. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lockwood CJ, Toti P, Arcuri F, Paidas M, Buchwalder L, Krikun G, Schatz F. Mechanisms of abruption-induced premature rupture of the fetal membranes: thrombin-enhanced interleukin-8 expression in term decidua. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1443–1449. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61230-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Buchholz KR, Stephens RS. Activation of the host cell proinflammatory interleukin-8 response by Chlamydia trachomatis. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1768–1779. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buchholz KR, Stephens RS. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway induces the inflammatory factor interleukin-8 following Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5924–5929. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01029-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abrahams VM, Aldo PB, Murphy SP, Visintin I, Koga K, Wilson G, Roberto R, Sharma S, Mor G. TLR6 Modulates First Trimester Trophoblast Responses to Peptidoglycan. J Immunol. 2008 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6035. In Press: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fischer SF, Vier J, Kirschnek S, Klos A, Hess S, Ying S, Hacker G. Chlamydia inhibit host cell apoptosis by degradation of proapoptotic BH3-only proteins. J Exp Med. 2004;200:905–916. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhong Y, Weininger M, Pirbhai M, Dong F, Zhong G. Inhibition of staurosporine-induced activation of the proapoptotic multidomain Bcl-2 proteins Bax and Bak by three invasive chlamydial species. J Infect. 2006;53:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Holland SM, DeLeo FR, Elloumi HZ, Hsu AP, Uzel G, Brodsky N, Freeman AF, Demidowich A, Davis J, Turner ML, Anderson VL, Darnell DN, Welch PA, Kuhns DB, Frucht DM, Malech HL, Gallin JI, Kobayashi SD, Whitney AR, Voyich JM, Musser JM, Woellner C, Schaffer AA, Puck JM, Grimbacher B. STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1608–1619. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang J, Liao X, Agarwal MK, Barnes L, Auron PE, Stark GR. Unphosphorylated STAT3 accumulates in response to IL-6 and activates transcription by binding to NFkappaB. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1396–1408. doi: 10.1101/gad.1553707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Klein C, Wustefeld T, Assmus U, Roskams T, Rose-John S, Muller M, Manns MP, Ernst M, Trautwein C. The IL-6-gp130-STAT3 pathway in hepatocytes triggers liver protection in T cell-mediated liver injury. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:860–869. doi: 10.1172/JCI200523640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lim SP, Garzino-Demo A. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein up-regulates the promoter activity of the beta-chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in the human astrocytoma cell line U-87 MG: role of SP-1, AP-1, and NF-kappaB consensus sites. J Virol. 2000;74:1632–1640. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1632-1640.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.O'Connor W, Jr., Harton JA, Zhu X, Linhoff MW, Ting JP. Cutting edge: CIAS1/cryopyrin/PYPAF1/NALP3/CATERPILLER 1.1 is an inducible inflammatory mediator with NF-kappa B suppressive properties. J Immunol. 2003;171:6329–6333. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gray JS, Pestka JJ. Transcriptional regulation of deoxynivalenol-induced IL-8 expression in human monocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2007;99:502–511. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoffmann E, Thiefes A, Buhrow D, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Schneider H, Resch K, Kracht M. MEK1-dependent delayed expression of Fos-related antigen-1 counteracts c-Fos and p65 NF-kappaB-mediated interleukin-8 transcription in response to cytokines or growth factors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9706–9718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]