Abstract

Neurons within the medial bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTm) that produce arginine vasotocin (VT; in non-mammals) or arginine vasopressin (VP; in mammals) have been intensively studied with respect to their anatomy and neuroendocrine regulation. However, almost no studies have examined how these neurons process stimuli in the animals’ immediate environment. We recently showed that in five estrildid finch species, VT-immunoreactive (-ir) neurons in the BSTm increase their Fos expression selectively in response to positively-valenced social stimuli (i.e., stimuli that should elicit affiliation). Using male zebra finches, a highly gregarious estrildid, we now extend those findings to show that VT-Fos coexpression is induced by a positive social stimulus (a female), but not by a positive non-social stimulus (a water bath in bath-deprived birds), although the female and bath stimuli induced Fos equally within a nearby control region, the medial preoptic nucleus. In concurrent experiments, we also show that the properties of BSTm VT-ir neurons strongly differentiate males that diverge in social phenotype. Males who reliably fail to court females (“non-courters”) have dramatically fewer VT-ir neurons in the BSTm than do reliable courters, and the VT-ir neurons of non-courters fail to exhibit Fos induction in response to a female stimulus.

Keywords: vasotocin, vasopressin, sexual behavior, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

Introduction

Parvocellular neurons that produce arginine vastotocin (VT) or arginine vasopressin (VP) are present in the medial bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTm) of almost all land vertebrates (reviews: Moore and Lowry, 1998; Goodson and Bass, 2001; De Vries and Panzica, 2006). For the last 25 years, an extraordinary amount of research has been focused on these cells and their projections, such that we now know a great deal about their hormonal regulation, seasonal plasticity, sexual dimorphism, and development. These features have been examined in a wide variety of species, thus we also know a great deal about species differences in anatomical features such as VT/VP cell numbers in the BSTm, and the density of projections to extrahypothalamic brain sites, particularly the lateral septum (LS; see reviews cited above). Most or all of the VT/VP projections to the LS arise from the neurons of the BSTm, and those BSTm neurons likely innervate other behaviorally-relevant regions as well, including the habenula, midbrain central gray, diagonal band of Broca, and the ventral pallidum (De Vries and Buijs, 1983; De Vries and Panzica, 2006). Manipulations within those areas demonstrate that VT/VP is involved in a broad range of social behaviors, including communication, pair bonding, parental behavior and aggression, and some of these behaviors are influenced in a species-specific manner (reviews: De Vries and Panzica, 2006; Lim and Young, 2006; Caldwell et al., 2008; Goodson, 2008)

Despite this vast literature, there remains one very large hole: We know almost nothing about the kinds of stimuli that these neurons process on a moment-to-moment or short-term basis. We recently addressed this issue in a study of five species of estrildid finches that differ selectively in their species-typical group sizes (“sociality”) (Goodson and Wang, 2006). Two of the species are relatively asocial and live year-round as territorial pairs; two of the species are highly gregarious and breed in large colonies; and one of the species is modestly gregarious. Subjects were placed in a novel, quiet environment (which limited overt behavioral responses such as territorial aggression), and were then simply exposed to a same-sex conspecific through a wire barrier. Although this paradigm elicited only arousal and orienting behaviors, it nonetheless produced very different Fos responses in the VT-immunoreactive (-ir) neurons of social and asocial species. For instance, a robust increase in VT-Fos colocalization was observed in the highly gregarious zebra finch following exposure to a same-sex conspecific, whereas the same manipulation produced a significant decrease in colocalization in the territorial violet-eared waxbill (Uraeginthus granatina). These species differences appear to reflect the valence of the social stimulus (positive-negative), since exposure of territorial waxbills to their pair bond partners elicited a large increase in VT-Fos colocalization, and conversely, social induction of Fos in the gregarious zebra finch was blocked by subjugation. Consistent with these findings, the three flocking species exhibited significantly higher baseline coexpression of VT and Fos than did the territorial species, and the two highly colonial species (the more social of the flocking species) exhibited significantly more VT-ir neurons in the BSTm than did the other species.

This series of discoveries suggested the general hypotheses being tested here – that the function and anatomy of BSTm VT neurons are important for the performance of appetitive courtship behavior and for the display of different courtship phenotypes. Specifically, we predict that higher expression of directed singing will correlate with higher levels VT neuronal activity, and that constitutive differences in courtship will correlate with VT cell number. We additionally sought to determine whether VT neurons of the BSTm respond only to positive stimuli that are social in nature, or whether they also respond to positive stimuli that not social.

Although the idea that VT/VP neurons in the BSTm play an important role in positive affiliation is not new, indirect evidence suggests that these neurons (and/or their projections to the LS) may also be functionally relevant to negative social contexts such as resident-intruder aggression (e.g., Bester-Meredith et al., 1999; Scordalakes and Rissman, 2004; Maney et al., 2005). However, functional data in birds and recent findings in mammals challenge this latter view (Goodson, 1998b; Goodson, 1998a; Goodson and Wang, 2006; Beiderbeck et al., 2007; also see Compaan et al., 1993; Everts et al., 1997), and suggest that the VT/VP neurons of the BSTm primarily mediate responses to positive social stimuli (Goodson and Wang, 2006) and/or promote non-aggressive social interaction (Landgraf et al., 2003). In this regard, they are quite distinct from the various hypothalamic VT/VP populations, including the anterior hypothalamic VP neurons that are well known to facilitate resident-intruder aggression in Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) (Ferris et al., 1997; Jackson et al., 2005; also see Gobrogge et al., 2007), and the paraventricular VT/VP neurons (or their homologues in anamniotes) that respond to stressors in every vertebrate group (reviews: Goodson and Bass, 2001; Engelmann et al., 2004; Caldwell et al., 2008). We now show that, not only are the BSTm VT neurons functionally distinct, they also process social stimuli to the exclusion of non-social stimuli, and they dichotomize courting and non-courting males.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 49 male zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) were used in the present experiments. All subjects were in full adult plumage a minimum of four months prior to use. One month prior to sacrifice, subjects were transferred from mixed-sex cages to same-sex cages. Birds were housed on a 15L:9D photoperiod with full-spectrum lighting and were provided finch seed mix and water ad libitum. Subjects could hear but not see females that were housed in the same room. Procedures were conducted legally and humanely in compliance with all applicable institutional and federal guidelines, including the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Behavioral procedures for Experiment 1

For this first, small experiment, ten males were selected that had exhibited a wide range of courtship singing during informal behavioral pre-screenings (conducted as part of student training). Three of these males did not reliably court during screenings. On the day of testing and perfusion, lights in the housing room remained off at what would normally be the beginning of the light period. Subjects were moved into a small cage (31 cm W × 20 cm H × 36 cm D) in a quiet room. A wire barrier was inserted into the cage, splitting it into left and right halves. A single perch paralleled each side of the wire barrier. A female stimulus was placed in the cage on the side opposite from the subject. Observations were conducted from behind a plastic curtain “blind” and the number of directed songs (i.e., courtship songs) given by the subject was recorded for 10 min. Subjects then were immediately placed back into the dark housing room. Perfusions were conducted 90 min after the beginning of the behavioral test.

Behavioral procedures for Experiment 2

Based on the results from Experiment 1, a second larger experiment was conducted to test the hypotheses that the difference in VT-Fos colocalization between courting and non-courting males, as observed in Experiment 1 (see Results), reflects 1) a lower level of constitutive VT-Fos colocalization in non-courters than in courters, perhaps reflecting constitutive differences in the motivation to court, and/or 2) a lack of phasic Fos response to the female stimulus in non-courting males. We additionally sought to clarify whether non-courters exhibit fewer VT-ir neurons in the BSTm than do courters, since this comparison only approached significance in the first study (with a notably small n of non-courters).

In conjunction with this experiment, we also sought to determine whether the selectiveness of BSTm neurons for positively-valenced stimuli, as previously demonstrated for social stimuli (Goodson and Wang, 2006), extends to non-social stimuli as well. Data on stimulus selectivity should help clarify the nature of the deficits observed in non-courting males and provide novel information on the properties of BSTm VT/VP neurons. Given that zebra finches reliably bathe when open water is available (Zann, 1996), we employed a water bath as the positive non-social stimulus. In order to ensure robust bathing during the test period prior to sacrifice, weekly water baths were terminated one month prior to testing and the subjects received their water via sipper tubes.

All males in our colony (n =127) were screened for courtship behavior on two days by placing them singly into a housing cage containing a stimulus female for 4 min. Screenings were separated by at least two days. Twelve males did not sing on either screening day and were designated as “non-courters.” These non-courters were subsequently exposed to control conditions (n = 5) or a female (n = 7) on the final test day, as described more fully below.

We selected 27 other males that reliably courted females (“courters”) and divided them into three groups that were matched based courtship singing during the screenings. The mean number of directed songs given during screenings (i.e., during 8 total min of observation) was approximately 59 for all three groups of courters (with a range in each group of ~40–88). Courter groups were exposed to control conditions, a water bath or a female (n = 9 in each group).

Subjects were acclimated to testing rooms for 1 hr per day for three days prior to testing and sacrifice. On the afternoon before testing, each subject was placed singly into a cage in one of the quiet testing rooms, and the subject remained in the room overnight. The following morning after lights-on, the experimenter entered the room, turned off the lights, and used a flashlight to place a female, a water bath or nothing (for controls) into the subject’s cage. Lights were turned back on and observations were conducted from behind a curtain for 15 min, after which the stimuli were removed. Perfusions were conducted 90 min after the beginning of the behavioral test. Tests were conducted during the first 2 hrs of the light phase.

Histology and immunocytochemistry

Subjects were deeply anesthetized by isoflurane vapor and intracardially perfused with 0.1M phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed, post-fixed overnight and sunk in 30% sucrose for sectioning. Tissue was cut on a cryostat at a thickness of 40 μm. Three series of free-floating sections were collected into section cryoprotectant (FD NeuroTechnologies, Baltimore, MD) and stored at −80°C until processing.

Immunocytochemistry was performed as follows: Tissue was rinsed 6 × 10 min in 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.4), followed by 20 min in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 9.5, ceramic well plates placed into a shallow water bath heated to 70°C); 2 × 10 min in PBS; and 1 hr in PBS + 5.0% bovine serum albumin (BSA) + 0.3% triton-X. Tissue was then incubated with guinea pig anti-VP (1:1000; Bachem, Torrance CA) and rabbit anti-Fos (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz CA), diluted in PBS + 2.5% BSA + 0.3% triton-X + 0.05% sodium azide and incubated 40–44 hrs at 4°C. This was followed by two 30 min rinses in PBS; 1 hr in biotinylated goat anti-guinea pig secondary (8 ml/ml; Jackon ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA); 3 × 10 min in PBS; 2 h in goat anti-rabbit secondary conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (5 ml/ml) + streptavidin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (3 ml/ml) in PBS + 2.5% BSA + 0.3% triton-X. Alexa Fluors were purchased from Molecular Probes/Invitrogen (Eugene, OR), with custom cross-adsorption against guinea pig in the goat anti-rabbit 594. Sections were extensively washed in PBS prior to mounting. Tissue was mounted on slides and coverslipped with ProLong Gold containing DAPI nuclear stain (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen).

Data analysis

Slides were coded for observer-blind analysis. Quantification of VT-Fos double-labeling was conducted on a Zeiss Axioscop microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) using a 62x objective and 10x eyepieces. Counts were made bilaterally at two levels of the BSTm – above the anterior commissure and in the VT cell band that extends ventromedially behind the caudal margin of the anterior commissure. In addition, photomicrographs of the BSTm and medial preoptic area (commissural level) were generated for the quantification of Fos labeling. All photomicrographs were taken at 10x using a Zeiss Axioscop microscope and an Optronics Magnafire digital camera (Optronics, Golena, CA) connected to a Macintosh computer. Counts of Fos-ir nuclei were conducted within standardized polygons or boxes that were superimposed on the digital photomicrographs using Adobe Photoshop 7 (Adobe Systems, Seattle, WA USA). Dots were placed over each labeled cell (in a separate Photoshop layer) and the dots were then thresholded and counted using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Most analyses were conducted parametrically using regressions and ANOVA followed by Fisher’s protected least significant difference (PLSD). Due to a small n of non-courters in Experiment 1, group data were analyzed non-parametrically using Mann-Whitney U tests. All tests were two-tailed with an alpha of 0.05.

Results

Experiment 1: VT neuronal profiles distinguish courting and non-courting males

Our first experiment was a small study designed to test the hypothesis that Fos expression in VT-ir neurons of the BSTm would correlate with the performance of appetitive courtship behavior. We therefore selected ten males that exhibited a wide range of directed song when presented with a female stimulus. Three of these males did not exhibit any directed song in the test prior to sacrifice and the other seven sang 5–63 songs. Contrary to expectations, the number of directed songs did not correlate with the percent of VT-ir neurons that expressed Fos-ir nuclei (r2 = .138; P > 0.05; n = 10). Nor did the number of VT-ir neurons correlate with directed song (r2 = .064; P > 0.05; n = 10). Rather, we found that all males that sang during the test – regardless of how much they sang – exhibited uniformly high levels of VT-Fos colocalization (87.9 ± 10.0% of VT-ir neurons contained Fos-ir nuclei). However, non-courters showed significantly lower levels of VT-Fos colocalization than did the subjects that sang (50.6 ± 22.8% in non-courters; P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U), and non-courters tended to exhibited fewer VT-ir neurons (5.3 ± 8.0 vs. 30.9 ± 24.3 neurons per section in non-courters and courters, respectively; P = 0.052, Mann-Whitney U). One of the three non-courting males exhibited no VT-ir neurons at all and therefore was not included in analyses of VT-Fos colocalization.

Experiment 2: VT neurons select for social stimuli and reflect behavioral phenotype

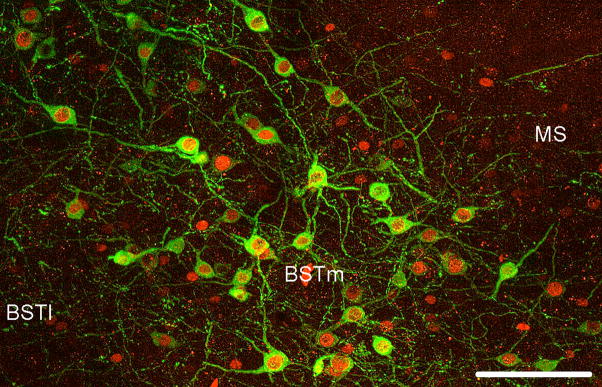

Based on the results of the first study, a second experiment was conducted to test the hypotheses (not mutually exclusive) that the differences in VT-Fos colocalization between courting and non males reflect differences in 1) the constitutive motivation to court, and/or 2) the phasic expression of song or lack of song. The first hypothesis yields the prediction that non-courters will exhibit lower levels of VT-Fos colocalization under control conditions, whereas the second hypothesis yields the prediction that non-courters fail to increase Fos expression in VT-ir neurons when the subjects are exposed to a female. We also sought to clarify whether non-courters exhibit fewer VT-ir neurons in the BSTm than do courters (this comparison approached significance in the first study). Finally, we sought to determine whether the selectiveness of BSTm neurons for positively-valenced stimuli, as previously demonstrated for social stimuli (Goodson and Wang, 2006), extends to non-social stimuli as well. Representative double-labeling from this experiment is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Double-labeling for VT (Alexa Fluor 488; green) and Fos (Alexa Fluor 594; red) in the BSTm of a normal (courter) male following a water bath, showing an approximately equal mix of single- and double-labeled VT cells. This level of double-labeling is representative of control and water bath subjects. Corresponding locations in the two panels are indicated by an asterisk. Scale bars = 100 μm in A and 50 μm in B. Other abbreviations: AC, anterior commissure; MS, medial septum; v, ventricle.

VT-Fos colocalization

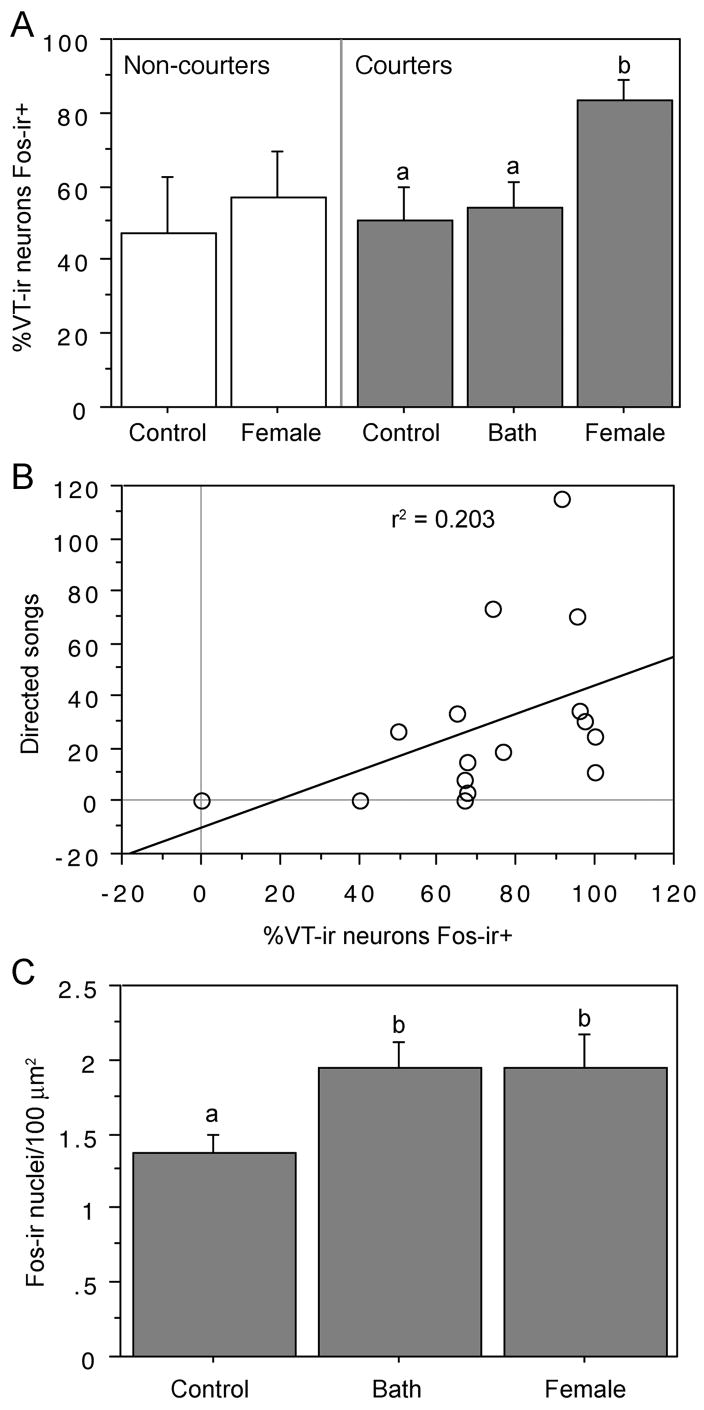

As described in the Methods, constitutive motivation to court was assessed in two behavioral screenings of 127 males, and we identified 12 males that reliably failed to court when provided an opportunity. These males were sacrificed following exposure to a female or control conditions. There was no difference in VT-Fos colocalization between non-courter groups exposed to control conditions and those exposed to females (F(1,10) = 0.273; P > 0.10; Fig. 2A). However, four of the non-courters that were exposed to females sang a modest amount to the female stimulus in this final test (3–27 songs each), which may have been promoted by overnight isolation in the testing room. These males tended to exhibit higher levels of VT-Fos colocalization than did the males that who did not sing (P = 0.077, Mann-Whitney U).

Figure 2.

VT-Fos colocalization in the BSTm increases differentially to social and non-social stimuli and distinguishes courting from non-courting males: (A) Percentage of VT-ir neurons that exhibit Fos-ir nuclei in non-courter controls and groups of courter males (matched for levels of constitutive courtship motivation; see Methods) that were exposed to control conditions (n = 9), a non-social reinforcer (water bath; n = 8), or a social reinforcer (female; n = 9). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Different letters above the error bars indicate significant differences between courter groups (Fisher PLSD P < 0.05 following significant ANOVA). Non-courter groups did not differ (P > 0.10; paired t-test). (B) Regression of VT-Fos colocalization and directed song in the final test reveals no significant relationship (P > 0.10). (C) Evidence that the water bath is an effective stimulus: BATH and FEMALE subjects expressed significantly more Fos-ir nucei/100 μm2 in the POM than did controls. Statistical conventions as in panel A.

VT-Fos colocalization was additionally quantified in groups of courters were that exposed to control conditions, a water bath, or a female. Of the nine subjects that were provided with a bath, only one failed to bathe during the 15-min test period, and this subject was dropped from the experiment. Courter males that were exposed to females exhibited significantly higher levels of VT-Fos colocalization than did the water bath and control subjects (F(2,23) = 6.480 P = 0.005; Fig. 2A), and these latter two groups exhibited virtually identical levels of VT-Fos colocalization.

Notably, VT-Fos colocalization did not correlate with the number of directed songs exhibited by males exposed to females (for courters only, r2 = .096; P > 0.05; n = 9; for courters and non-courters combined, r2 = .203; P > 0.05; n = 9; Fig. 2B), and all subjects exposed to females exhibited very high levels of colocalization with very little variation across subjects (cf. Fig. 2B and data reported above for Experiment 1). The virtually identical levels of VT-Fos colocazation in Experiment 1(in which males courted females through a wire barrier) and Experiment 2 (in which the subjects and stimulus females interacted freely) indicate that physical contact is not necessary to obtain a full Fos response in the VT-ir neurons.

Effectiveness of the bath stimulus

In order to verify that the water bath was an effective stimulus, we analyzed data from the courter groups for overall numbers of Fos-ir nuclei in the BSTm and a nearby region, the medial preoptic nucleus (POM), an area that is involved in both osmoregulation and courtship (Sharp et al., 1995; Ball et al., 2002). The POM exhibited significant and equivalent responses to both the water bath and female stimuli (F(2, 23) = 3.692, P < 0.05; Fig. 2C). Near-significant differences were also observed in the BSTm (F(2, 23) = 3.176, P = 0.06), with the water bath subjects being intermediate to the other two groups (control, 1.540 ± 0.105; water bath 1.788 ± 0.159; female, 2.002 ± 0.134 Fos-ir nuclei/100 μm2).

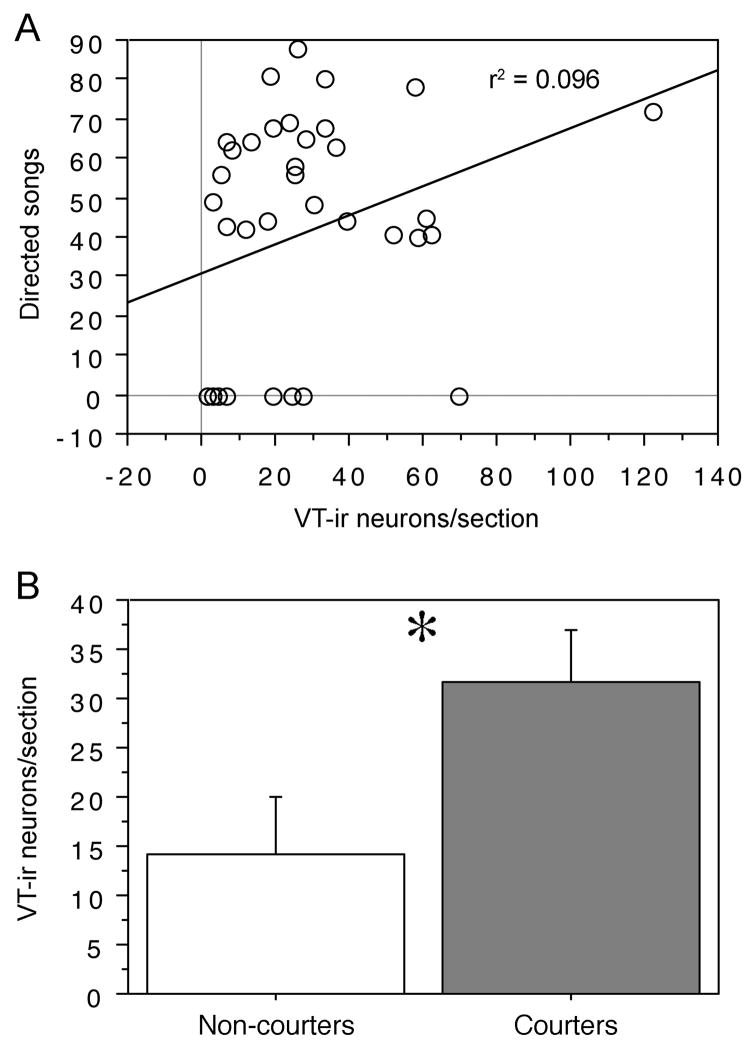

Correlations between VT-ir cell number and behavior

The number of VT-ir neurons in the BSTm showed a near-significant correlation with the number of songs that males sang to females in the behavioral pre-screenings (r2 = .096; P = 0.059; n = 38; Fig. 3A). However, this trend was mainly driven by the inclusion of non-courters, and when the analysis was restricted to courters, the correlation trend convincingly disappeared (r2 = .0004; P = 0.916; n = 26). Relative to the 26 courters, the 12 non-courters exhibited a large and significant deficit in the number of VT-ir neurons (t = −2.086, P < 0.05, Student’s t-test; Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

VT-ir cell number in the BSTm differentiates courting and non-courting males: (A) The number of VT-ir neurons in the BSTm (shown as neurons per 40 μm section) shows a near-significant correlation with the number of songs that subjects sang during the two 4-min behavioral pre-screenings (P = 0.059), although this correlation driven by the large difference between courters and non-courters, not by variation among courters (see Results). (B) Non-courting males (n = 12) exhibit significantly fewer VT-ir neurons than do courting males (n = 26; *P < 0.05, Student’s unpaired t test).

Gonadosomatic index (GSI)

In order to determine whether gonadal function may be a factor in the findings presented above, we calculated a GSI (gonad-to-body weight ratio) for each of the subjects. GSI correlates significantly with the number of songs exhibited in pre-screenings (r2 = .113; P < 0.05; n = 38), suggesting that GSI is a behaviorally relevant measure. However, the significance of this correlation was strongly driven by the difference between courters and non-courters (non-courters had significantly lower GSI values than courters; 0.002 ± 0.00025 vs. 0.003 ± 0.00018, respectively; t = −3.283, P < 0.01). Indeed, if the analysis is restricted to the courter males, there is a weakly negative relationship between GSI and pre-screening song (r2 = .133; P = 0.067; n = 26). Importantly, GSI did not correlate with any of our main dependent measures, including VT-ir cell number (r2 = .004; P > 0.10, n = 38), level of VT-Fos colocalization in control subjects (r2 = .053; P > 0.10, n = 14) or level of VT-Fos colocalization in subjects exposed to females (r2 = .062; P > 0.10, n = 16).

Discussion

Previous experiments have established that VT-ir neurons of the BSTm are sensitive to stimulus valence (positive-negative) (Goodson and Wang, 2006). We now show that Fos responses of these neurons are further restricted to stimuli of a social nature, and that these cells also exhibit characteristics that distinguish social phenotypes. As demonstrated in both of the present experiments, male zebra finches that reliably fail to court females (“non-courters”) exhibit both anatomical and functional deficits in the VT-ir cell group of the BSTm. Non-courters express less than half the number of VT-ir neurons than that of normal males, and those neurons fail to increase their Fos expression following exposure to a female. In gregarious animals such as the zebra finch, the VT-ir neurons of the BSTm normally increase their Fos expression following exposure to almost any conspecific stimulus (including individuals of either sex) (Goodson and Wang, 2006), thus the lack of Fos response in the VT neurons of non-courting males suggests the possibility that the social impairments of non-courters may extend beyond their deficiencies in courtship.

Are the VT profiles of courters and non-courters truly constitutive?

In most species that have been examined, the VT/VP neurons of the BSTm are highly sensitive to sex hormones (reviews: Goodson and Bass, 2001; Panzica et al., 2001; De Vries and Panzica, 2006), so it is important to question whether VT differences between courters and non-courters may be related to differences in adult hormone levels. A few pieces of evidence suggest that this is not the case. First, although non-courters exhibit lower gonad-to-body weight ratios than do courters, these ratios show a convincing lack of correlation with VT-ir cell number in the BSTm. Testosterone treatment in female zebra finches likewise produces no change in VT immunoreactivity (Voorhuis and De Kloet, 1992). Furthermore, even in male zebra finches that have been housed long-term under reproductively non-stimulatory (same-sex) conditions, the VT-ir neurons of the BSTm still show robust, socially-induced Fos expression (Goodson and Wang, 2006), suggesting that the lack of Fos induction in non-courters is not attributable to gonadal state.

The hormonal insensitivity of VT neurons in zebra finches contrasts sharply with those from the vast majority of birds (e.g., Serinus canaria, Voorhuis et al., 1988; Coturnix japonica, Viglietti-Panzica et al., 1992: Junco hyemalis, Plumari et al., 2004), and other vertebrate species that have been examined (reviews: Goodson and Bass, 2001; Panzica et al., 2001; De Vries and Panzica, 2006). However, zebra finches are unusually opportunistic breeders (Zann, 1996), and thus the lack of hormonal effects on VT protein may represent an adaptation that has evolved to keep reproduction-related circuits “at the ready.” Issues of hormone sensitivity aside, recent data from our lab indicate that the non-courting phenotype is stable with repeated testing over a period of months (D. Kabelik and J. L. Goodson, unpubl. obs.).

Courters and non-courters are distinguished by VT-ir neurons that are socially-selective and valence-sensitive

The present experiments demonstrate strong differences in the anatomy and responsiveness of the BSTm VT cell group between courters and non-courters. To determine what those differences mean, we must first consider what “kind” of information is being encoded by the BSTm VT neurons to begin with, which should tell us about the nature of the information being conveyed to post-synaptic projection targets of the BSTm VT neurons.

Until recently, the only data relevant to this question came from experiments with male prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Following cohabitation with a female, males exhibit an upregulation of VP mRNA in the BSTm (Wang et al., 1994b), but a decrease in VP-ir innervation of the LS and habenula (Bamshad et al., 1994). Together, these findings suggest that BSTm VP neurons are increasing both production and release of peptide. Such an increase in VP production could influence a variety of behaviors, including pair bonding, mating-induced aggression, and paternal care – all behaviors that are influenced by VP in male prairie voles (Winslow et al., 1993; Wang et al., 1994a). However, these data do not allow us to pinpoint the specific aspects of cohabitation that are driving the increase in VP mRNA. That is, the VP neurons could be responding to many different things in the cohabitation context, such as general arousal, social arousal, olfactory signaling, copulation, bonding, etc., or perhaps a more complex stimulus dimension such as valence.

Recent data in estrildid finches support this latter interpretation – that the BSTm VT/VP neurons respond primarily to valence, and increase their Fos expression selectively to “positive” social stimuli (i.e., those that elicit affiliation or approach) (Goodson and Wang, 2006). Even very intense social stimuli are not sufficient to elicit a Fos response in BSTm VT neurons if the stimuli are “negative” (i.e., stimuli that would elicit avoidance or territorial aggression). For instance, during competition for mates, zebra finches show a robust increase in VT-Fos colocalization over control subjects, but this increase is not observed if subjects experience extreme subjugation during the competition (Goodson and Wang, 2006).

The present experiments now extend those findings to show that Fos responses of the BSTm VT neurons are further restricted to stimuli that are social in nature. This conclusion is supported by the fact that our positive non-social stimulus, a water bath, failed to induce a Fos response within the BSTm VT neurons. Zebra finches inhabit arid regions of Australia and bathe regularly whenever it is possible to do so (Zann, 1996). Although the bath stimulus was “ignored” by the VT neurons, it did elicit a Fos response within a nearby control region, the medial preoptic area, and that response was virtually identical to the Fos response elicited by a female. Thus, the bath was sufficient to generate strong Fos responses, but not within VT neurons of the BSTm. Although the possibility remains that these neurons respond to non-social stimuli via cellular mechanisms that do not include Fos expression, it is nonetheless clear that BSTm VT neurons exhibit functional mechanisms that do discriminate positive social stimuli from positive non-social stimuli.

Behavioral significance of VT neuronal activity and distinct VT phenotypes

Based on the valence sensitivity of BSTm VT neurons, as just described, it is natural to expect that 1) the VT neurons of non-courters do not process females as positive social stimuli, and 2) subsequent deficits will be observed in the appetitive approach to females and in the display of directed song. Although these are logical hypotheses, the second hypothesis must be rejected, since multiple experiments in male zebra finches demonstrate that courtship singing is not impacted by central infusions of a VP V1a antagonist or exogenous VT (Goodson and Adkins-Regan, 1999; Goodson et al., 2004). VT does influence courtship via peripheral actions on gonadal hormones (and in a negative manner), but these actions are almost certainly divorced from the central functions of VT neurons in the BSTm (Harding and Rowe, 2003).

Although differences in VT phenotype between courters and non-courters probably do not relate to courtship singing per se, VT infusions into the septum or lateral ventricle do facilitate “mate competition aggression” (a form of aggression that is specifically tied to the context of courtship; see Adkins-Regan and Robinson, 1993) and this effect is reversed by a V1a antagonist (Goodson and Adkins-Regan, 1999; Goodson et al., 2004). Hence, the deficits observed here for non-courters may primarily reflect a lack of competitive behavior. Importantly, the role of endogenous VT in natural pair bond formation also remains to be tested.

Conclusions

VT/VP neurons of the BSTm have been the focus of much study, particularly from a neuroendocrine perspective, but very little data are available on the response characteristics of those neurons. However, using species of estrildid finches that allow sociality to be isolated as a quasi-independent variable, we recently showed that these neurons are sensitive to stimulus valence. We now extend those findings to show that VT-ir neurons in the BSTm of zebra finches are selectively activated in response to social stimuli, and show no response to a positive non-social stimulus. These combined findings suggest a strong link between these neurons and affiliative behavior. In support of that view, we here present data from two experiments showing that non-courting males exhibit deficits in VT-ir cell number and VT-Fos colocalization that is associated with male-female interactions. Although we can obtain no evidence that these deficits directly impact courtship per se, there is good evidence to suggest that the deficits may relate to mate competition aggression, and perhaps pair bonding, as well.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant MH62656. We thank O. Gorobet, A. Kelly, C. Kemp, and D. Ki for assistance with cell counts.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adkins-Regan E, Robinson TM. Sex differences in aggressive behavior in zebra finches (Poephila guttata) J Comp Psychol. 1993;107:223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Ball GF, Riters LV, Balthazart J. Neuroendocrinology of song behavior and avian brain plasticity: multiple sites of action of sex steroid hormones. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2002;23:137–78. doi: 10.1006/frne.2002.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamshad M, Novak MA, De Vries GJ. Cohabitation alters vasopressin innervation and paternal behavior in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Physiol Behav. 1994;56:751–758. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiderbeck DI, Neumann ID, Veenema AH. Differences in intermale aggression are accompanied by opposite vasopressin release patterns within the septum in rats bred for low and high anxiety. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:3597–3605. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bester-Meredith JK, Young LJ, Marler CA. Species differences in paternal behavior and aggression in Peromyscus and their associations with vasopressin immunoreactivity and receptors. Horm Behav. 1999;36:25–38. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell HK, Lee HJ, Macbeth AH, Young WS., III Vasopressin: Behavioral roles of an “original” neuropeptide. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;84:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compaan JC, Buijs RM, Pool CW, Deruiter AJH, Koolhaas JM. Differential lateral septal vasopressin innervation in aggressive and nonaggressive male mice. Brain Res Bull. 1993;30:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries GJ, Buijs RM. The origin of the vasopressinergic and oxytocinergic innervation of the rat brain with special reference to the lateral septum. Brain Res. 1983;273:307–317. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries GJ, Panzica GC. Sexual differentiation of central vasopressin and vasotocin systems in vertebrates: Different mechanisms, similar endpoints. Neuroscience. 2006;138:947–955. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann M, Landgraf R, Wotjak CT. The hypothalamic-neurohypophysial system regulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis under stress: an old concept revisited. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2004;25:132–149. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts HGJ, DeRuiter AJH, Koolhaas JM. Differential lateral septal vasopressin in wild-type rats: Correlation with aggression. Horm Behav. 1997;31:136–144. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris CF, Melloni RH, Koppel G, Perry KW, Fuller RW, Delville Y. Vasopressin/serotonin interactions in the anterior hypothalamus control aggressive behavior in golden hamsters. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4331–4340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04331.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobrogge KL, Liu Y, Jia X, Wang Z. Anterior hypothalamic neural activation and neurochemical associations with aggression in pair-bonded male prairie voles. J Comp Neurol. 2007;502:1109–1122. doi: 10.1002/cne.21364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL. Territorial aggression and dawn song are modulated by septal vasotocin and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in male field sparrows (Spizella pusilla) Horm Behav. 1998a;34:67–77. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL. Vasotocin and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide modulate aggression in a territorial songbird, the violet-eared waxbill (Estrildidae: Uraeginthus granatina) Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1998b;111:233–244. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1998.7112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL. Nonapeptides and the evolutionary patterning of sociality. Prog Brain Res. 2008;170:3–15. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00401-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL, Adkins-Regan E. Effect of intraseptal vasotocin and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide infusions on courtship song and aggression in the male zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:19–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL, Bass AH. Social behavior functions and related anatomical characteristics of vasotocin/vasopressin systems in vertebrates. Brain Res Rev. 2001;35:246–265. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL, Lindberg L, Johnson P. Effects of central vasotocin and mesotocin manipulations on social behavior in male and female zebra finches. Horm Behav. 2004;45:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL, Wang Y. Valence-sensitive neurons exhibit divergent functional profiles in gregarious and asocial species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17013–17017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606278103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding CF, Rowe SA. Vasotocin treatment inhibits courtship in male zebra finches; concomitant androgen treatment inhibits this effect. Horm Behav. 2003;44:413–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, Burns R, Trksak G, Simeone B, Deleon KR, Connor DF, Harrison RJ, Melloni RH., Jr Anterior hypothalamic vasopressin modulates the aggression-stimulating effects of adolescent cocaine exposure in Syrian hamsters. Neuroscience. 2005;133:635–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf R, Frank E, Aldag JM, Neumann ID, Sharer CA, Ren X, Terwilliger EF, Niwa M, Wigger A, Young LJ. Viral vector-mediated gene transfer of the vole V1a vasopressin receptor in the rat septum: improved social discrimination and active social behaviour. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:403–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MM, Young LJ. Neuropeptidergic regulation of affiliative behavior and social bonding in animals. Horm Behav. 2006;50:506–517. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maney DL, Erwin KL, Goode CT. Neuroendocrine correlates of behavioral polymorphism in white-throated sparrows. Horm Behav. 2005;48:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore FL, Lowry CA. Comparative neuroanatomy of vasotocin and vasopressin in amphibians and other vertebrates. Comp Biochem Physiol C Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol. 1998;119:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0742-8413(98)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzica GC, Aste N, Castagna C, Viglietti-Panzica C, Balthazart J. Steroid-induced plasticity in the sexually dimorphic vasotocinergic innervation of the avian brain: Behavioral implications. Brain Res Rev. 2001;37:178–200. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plumari L, Plateroti S, Deviche P, Panzica GC. Region-specific testosterone modulation of the vasotocin-immunoreactive system in male dark-eyed juncos, Junco hyemalis. Brain Res. 2004;999:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scordalakes EM, Rissman EF. Aggression and arginine vasopressin immunoreactivity regulation by androgen receptor and estrogen receptor alpha. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:20–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183x.2004.00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PJ, Li Q, Talbot RT, Barker P, Huskisson N, Lea RW. Identification of hypothalamic nuclei involved in osmoregulation using fos immunocytochemistry in the domestic hen (Gallus domesticus), ring dove (Streptopelia risoria), Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) and zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) Cell Tissue Res. 1995;282:351–361. [Google Scholar]

- Viglietti-Panzica C, Anselmetti GC, Balthazart J, Aste N, Panzica GC. Vasotocinergic innervation of the septal region in the Japanese quail: sexual differences and the influence of testosterone. Cell Tissue Res. 1992;267:261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Voorhuis TAM, De Kloet ER. Immunoreactive vasotocin in the zebra finch brain Taeniopygia guttata. Develop Brain Res. 1992;69:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(92)90116-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorhuis TAM, Kiss JZ, De Kloet ER, De Wied D. Testosterone-sensitive vasotocin-immunoreactive cells and fibers in the canary brain. Brain Res. 1988;442:139–146. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Ferris CF, De Vries GD. Role of septal vasopressin innervation in paternal behavior in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994a;91:400–404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Smith W, Major DE, De Vries GJ. Sex and species differences in the effects of cohabitation on vasopressin messenger RNA expression in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) and meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) Brain Res. 1994b;650:212–218. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91784-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow JT, Hastings N, Carter CS, Harbaugh CR, Insel TR. A role for central vasopressin in pair bonding in monogamous prairie voles. Nature. 1993;365:545–548. doi: 10.1038/365545a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zann RA. The zebra finch: a synthesis of field and laboratory studies. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1996. [Google Scholar]