Abstract

Background

Systematic reviews have, in the past, focused on quantitative studies and clinical effectiveness, while excluding qualitative evidence. Qualitative research can inform evidence‐based practice independently of other research methodologies but methods for the synthesis of such data are currently evolving. Synthesising quantitative and qualitative research in a single review is an important methodological challenge.

Aims

This paper describes the review methods developed and the difficulties encountered during the process of updating a systematic review of evidence to inform guidelines for the content of patient information related to cervical screening.

Methods

Systematic searches of 12 electronic databases (January 1996 to July 2004) were conducted. Studies that evaluated the content of information provided to women about cervical screening or that addressed women's information needs were assessed for inclusion. A data extraction form and quality assessment criteria were developed from published resources. A non‐quantitative synthesis was conducted and a tabular evidence profile for each important outcome (eg “explain what the test involves”) was prepared. The overall quality of evidence for each outcome was then assessed using an approach published by the GRADE working group, which was adapted to suit the review questions and modified to include qualitative research evidence. Quantitative and qualitative studies were considered separately for every outcome.

Results

32 papers were included in the systematic review following data extraction and assessment of methodological quality. The review questions were best answered by evidence from a range of data sources. The inclusion of qualitative research, which was often highly relevant and specific to many components of the screening information materials, enabled the production of a set of recommendations that will directly affect policy within the NHS Cervical Screening Programme.

Conclusions

A practical example is provided of how quantitative and qualitative data sources might successfully be brought together and considered in one review.

The National Health Service Cervical Screening Programme (NHSCSP) first published evidence‐based guidelines addressing the content of screening letters and leaflets in 1997.1The NHS Cancer Plan (September 2000) called for honest, comprehensive and understandable screening materials2 and a White Paper (November 2004) emphasised the need for up‐to‐date and factual health information.3 An important NHSCSP priority is the continual improvement of the quality of written information sent to women about cervical screening. As such, a review was commissioned in early 2004 to develop updated NHSCSP patient‐information guidelines. The focus of the review was directed and informed by two main questions:

What is the existing research evidence base regarding the content of the written information sent to women at all stages of the cervical screening process?

What are the information needs of women during cervical screening?

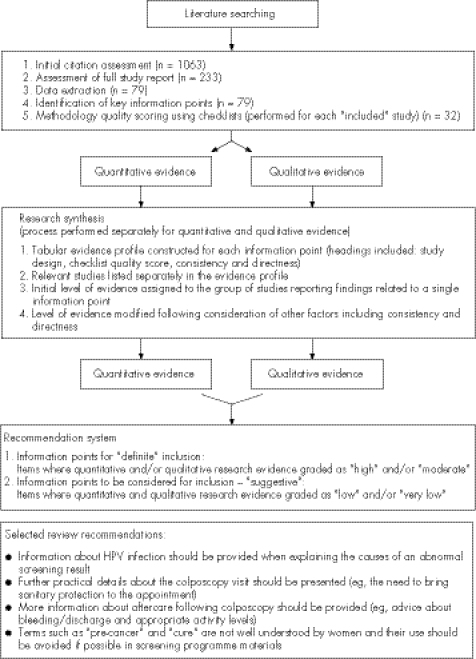

The main purpose of the review was to identify important information for inclusion in the screening programme letters and leaflets (introductory, abnormal result and colposcopy). Important information included facts (length of the screening interval), concepts (purpose of the screening test) and general points (suitable attire). For each key information point, a tabular summary was created of the relevant evidence. The full updated guidelines are described elsewhere.4 A selection of the review recommendations is presented in fig 1. The reviewers were experienced in conducting quantitative and qualitative research related to cancer screening and patient and health professional information.

Figure 1 The review process (including a selection of the review recommendations).

Systematic reviews

Conventional systematic reviews aim to bring together and summarise the available research addressing a question of interest so that inferences about findings may be guided by the most appropriate forms of evidence.5,6 Evidence synthesis systems have, in the past, given preference to quantitative studies (mainly randomised trials) and clinical effectiveness. Accordingly, explicit methods have been established for the systematic review of trial‐based evidence including comprehensive literature searching, detailed quality appraisal procedures and standard synthesis techniques.7,8,9,10 Interest is growing in the development of diverse systematic review methods to incorporate different types of evidence including other quantitative study designs as well as qualitative research.11 Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research are still in the early stages of proposal and evaluation,12,13 and the suitability of fitting various forms of qualitative research within the framework of conventional review methodology is an active research topic.11 There is, in fact, still debate about whether the synthesis of qualitative evidence is appropriate and whether it is acceptable to combine qualitative studies derived from different traditions.13,14,15

Limitations of traditional hierarchies of evidence

Traditional evidence hierarchies were developed specifically to address questions of efficacy and effectiveness6 and involved assessing research according to study design with the randomised trial as the premier form of evidence.7,16 This becomes problematic in areas of research dominated by non‐trial quantitative evidence owing to the lower quality scores subsequently assigned to these studies.17 Also, evidence syntheses concentrating on wider issues such as “How does it work?” or “What are patients' experiences?” require a different approach because these types of research questions are best answered by evidence from a variety of sources.15,18,19,20

Qualitative research

Qualitative evidence has a role to play in answering questions not easily evaluated by experimental studies.18,20,21 Although qualitative studies do not establish probability estimates or effect sizes, they can provide important support for quantitative outcomes and identify patient priorities and concerns.12 However, the usefulness of qualitative research is not limited to the explanation of process measures. In fact, qualitative research may address many healthcare questions directly and inform evidence‐based practice independently of other research methodologies.12,21,22

Importance of a range of evidence

Policy‐makers and practitioners assessing complicated healthcare questions draw on diverse sources of evidence during the decision‐making process.13,14,23 The development of methods for the synthesis of different types of research in a single review is an important methodological challenge. A number of approaches (narrative summary, thematic analysis, meta‐ethnography and bayesian methods) could be applied to the synthesis of both qualitative and quantitative research.12,13 However, most have evolved from techniques used for primary data analysis and were initially developed for either qualitative or quantitative data—not both.13 Several groups are currently working on methods for the incorporation of qualitative evidence into systematic reviews including the international Cochrane Qualitative Methods Group, the international Campbell Collaboration, the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre in the UK and the Joanna Briggs Institute in Australia.23 The UK Economic and Social Research Council has also funded a programme of research in this area.23,24

Box 1 First example of studies included in an updated review of evidence‐based guidelines for the content of NHSCSP letters and leaflets (the studies described were focused on colposcopy information)

Colposcopy information leaflets: what women want to know and when they want to receive this information28

-

Study design: The study was divided into two parts (A, B)

-

-

Qualitative component (Part A) and

-

-

Non‐comparative descriptive component (Part B)

-

-

-

Study aims:

-

-

To determine what information women want to receive about colposcopy and when they want to receive it

-

-

To evaluate how this relates to the NHSCSP guidelines

-

-

-

Population:

-

-

Part A: A total of 42 women with abnormal Pap smear results attending a pre‐colposcopy counselling session at a UK cancer centre colposcopy clinic

-

-

Part B: 100 consecutive women with abnormal Pap smear results newly referred to a UK cancer centre colposcopy clinic

-

-

-

Data collection:

-

-

Part A: Observation and documentation

-

-

Part B: Self‐report via questionnaire

-

-

-

Extracted information:

-

-

Part A: A list of 38 questions asked by 50% or more of the women at the pre‐colposcopy counselling session (eg, what is an abnormal smear? or what is colposcopy?)

-

-

Part B: Preferred timing of information delivery and information needs identified by women

-

-

-

Notes:

-

-

The third component of this study involved an assessment of information leaflets from 128 colposcopy clinics and is not described in this text box

-

-

Although methods of synthesising quantitative and qualitative research are beginning to be developed, few studies have been published that address the problem from a practical point of view.9,15,25,26 The current lack of specific guidance and accumulated experience in the synthesis of a range of research evidence leaves would‐be reviewers in a difficult position. The aim of this paper is to contribute to the debate by describing the review methods developed and difficulties encountered during the process of updating evidence‐based guidelines for the content of NHSCSP letters and leaflets.

Box 2 Second example of studies included in an updated review of evidence‐based guidelines for the content of NHSCSP letters and leaflets (the studies described were focused on colposcopy information)

An observational study of precolposcopy education sessions: what do women want to know?29

-

Study design:

-

-

Qualitative study

-

-

-

Study aims:

-

-

To observe group counselling educational sessions for women about colposcopy held before the procedure

-

-

To identify specific concerns about cervical cancer, the procedure of colposcopy and any longer term effects of the procedure

-

-

-

Population:

-

-

A total of 47 women with abnormal Pap smear results attending 1 of 5 precolposcopy group counselling educational sessions run by two specialist hospital colposcopy clinic nurses

-

-

-

Data collection:

-

-

Observation—participants' questions, comments and non‐verbal communication (eg, laughter or anxiety) were recorded verbatim

-

-

-

Extracted information:

-

-

Information needs identified by women

-

-

What is the evidence base?

The literature describing screening information content and women's information needs was dispersed among a variety of disciplines, and numerous research designs potentially addressed the review questions. Consequently, the review evidence base was complex and ill defined. This is not a unique problem, many healthcare questions are not easily evaluated solely by experimental methods (ie randomised trials) or other forms of quantitative investigation.12,15,17,27 Boxes 1–4 provide examples of the range of data sources included in the review (the four studies described were focused on colposcopy information).

Methods

Literature searching

Systematic searches of 12 electronic databases (January 1996 to July 2004 inclusive) were conducted. During the search development, a “test” subset of relevant studies was used to assess whether thesaurus or free‐text terms could be included in isolation. A combination of both was required to identify all the “test” studies. As discussed by Shaw et al,32 the cost of designing a comprehensive search strategy is the lack of precision. Study design filters may help improve precision, however none were incorporated in this work because of concerns about poor indexing in electronic databases—particularly for qualitative studies.9,18,20,32,33,34 Instead, a core set of subject specific terms (cervical smears, colposcopy, screening and neoplasms) was used in combination with thesaurus and general free‐text terms such as “leaflet*”, “knowledge” or “understand*” to identify relevant studies.

Box 3 Third example of studies included in an updated review of evidence‐based guidelines for the content of NHSCSP letters and leaflets (the studies described were focused on colposcopy information)

Patient‐based evaluation of a colposcopy information leaflet.30

-

Study design:

-

-

Non‐comparative descriptive study

-

-

-

Study aims:

-

-

To evaluate an information leaflet, “Prevention of cervical cancer,” routinely sent to women referred for colposcopy

-

-

To use the findings of the evaluation to propose changes to the leaflet

-

-

-

Population:

-

-

A total of 137 women with abnormal Pap smear results newly referred to the Ninewells Hospital colposcopy clinic in Dundee, Scotland

-

-

-

Data collection:

-

-

Self‐report via questionnaire

-

-

-

Extracted information:

-

-

Information leaflet text (terms and language used)

-

-

Information needs identified by women

-

-

Satisfaction with information provided

-

-

-

Notes:

-

-

Text of information leaflet included with the study report

-

-

Additional references were taken from the table of contents of selected journals, reference sections of relevant studies, and the NHSCSP research literature online database (http://www.nhs.thescienceregistry.com/main.asp). Grey literature was sought from internet resources and contact with subject area specialists. In total, 1063 citations were identified (both published and unpublished, with no language restrictions).

Initial citation and full study report assessments

Titles and abstracts of citations were independently prescreened by two reviewers according to review study selection criteria (box 5). Others have noted that when present, the abstracts of qualitative studies vary in content (ie, study design details may not be reported).32,34 The inclusion or exclusion criteria were liberally applied and if doubt existed, individual studies were provisionally included for consideration on the basis of full text reports. Only about 3% of the screened citations lacked an abstract.

A total of 233 studies were retrieved for further evaluation. Two reviewers independently assessed the full study reports; any uncertainty was resolved by discussion. Most of the the exclusions fell into three categories: studies reporting interventions aimed at increasing screening uptake (35), non‐UK based studies investigating non‐generalisable cervical screening issues (41), and studies focused on aspects of cervical screening other than written information materials (51). The remaining 27 excluded studies belonged to several different categories listed in box 5. An important consideration for prospective reviewers is the time required to complete the search strategy development as well as the initial citation and full study report assessments. In this review, around 4 months of full‐time work was dedicated to these preliminary steps.

Box 4 Fourth example of studies included in an updated review of evidence‐based guidelines for the content of NHSCSP letters and leaflets (the studies described were focused on colposcopy information)

Is the provision of information leaflets before colposcopy beneficial? A prospective randomised study31

-

Study design:

-

-

Randomised controlled trial

-

-

-

Study aims:

-

-

To assess the usefulness of a leaflet sent to women before colposcopy in reducing anxiety

-

-

-

Population:

-

-

A total of 210 women diagnosed with moderate dyskaryosis or less newly referred to the North Staffordshire colposcopy clinic

-

-

-

Intervention:

-

-

Intervention group: information leaflet sent with clinic appointment letter

-

-

Control group: clinic appointment letter only

-

-

-

Data collection:

-

-

Self‐report via questionnaire

-

-

-

Extracted information:

-

-

Information leaflet text (terms and language used)

-

-

Information leaflet assessment (intervention group only)

-

-

-

Notes:

-

-

Text of information leaflet included with the study report

-

-

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted for 79 studies (52 quantitative and 27 qualitative). A data extraction form was used to record full study details and guide decisions about the relevance of individual studies to the review questions. The form was developed using guidelines produced by the UK National Health Service Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)3 and other publications.35,36,37 Similar information was extracted for all studies and included: aims, setting, population, research design, methods, interventions (if appropriate), results and conclusions. Data were extracted from relevant studies by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer.

Identification of key information points

A core set of key information points for the screening programme letters and leaflets was developed from the 1997 guidelines1 and the extracted data. All the information points from the original guidelines as well as new points identified from the findings of the data extracted studies were included in the core set. In total, 32 studies reported relevant results (the range of study designs is described in box 6). Although a large number of studies underwent data extraction and ultimately many did not report relevant findings, it was essential to consider a variety of potentially applicable studies to obtain a comprehensive set of key information points. The excluded studies fell into the following categories: studies reporting interventions aimed at increasing screening uptake (n = 3), non‐UK based studies investigating non‐generalisable cervical screening issues (n = 3), studies focused on aspects of cervical screening other than written information materials (n = 14) and studies containing information‐related findings not directly relevant to the agreed key information points (n = 20). A further seven studies (five quantitative and two qualitative) contained insufficient information about study design, methods of analysis and findings for a full assessment.

Box 5 Study selection criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Population:

-

-

Women, 20–64 years

-

-

-

Setting:

-

-

Organised, systematic cervical screening programme (screening delivered in GP surgeries, community or hospital clinics)

-

-

-

Research Questions:

-

-

Assessment of the content of written information materials provided to women about cervical screening at all stages of the cervical screening process

-

-

Investigation of the information needs of women at all stages of the cervical screening process

-

-

-

Study designs:

-

-

All (except for opinion pieces)

-

-

Exclusion criteria

Interventions focused on medical professional education, general practice performance and systems, cervical screening technology, protocols and technical aspects of treatment for cervical intra‐epithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer

Interventions that aimed to increase cervical screening uptake (except where the content of participant information materials was evaluated and/or included with the study report)

Studies reporting non‐information based predictors of screening uptake and risk factors for cervical cancer

Studies reporting knowledge, attitudes, health beliefs or barriers towards cervical screening without reference to written information materials or information needs

Non‐UK based studies investigating cervical screening issues not generalisable to the UK screening population and/or setting

Studies reporting insufficient information about study design, methods of analysis and findings for a full assessment

Studies reporting information‐related findings not directly relevant to the core set of key information points

Study methodology—quality scoring

Study quality appraisal is undertaken in quantitative systematic reviews to assess bias—for example, appropriate randomisation for trials—and to identify other study design specific defects.11,38 Many quality appraisal checklists are available for different types of quantitative evidence however, for study designs other than randomised trials, the key elements of quality are not as well agreed.38 The issue of how or whether to assess qualitative studies is a matter of some debate.13,14,33,39,40 The UK NHS CRD guidance favours structured appraisal of qualitative research but recognises that consensus is lacking on appropriate criteria.7

Although the exact function of quality appraisal in reviews of quantitative and qualitative evidence is controversial, it is recognised that reviewers should highlight evidence quality issues—in conduct, reporting, or both for review users.13 As such, the quality of each individual study included in the review was assessed by two reviewers using established checklists. Separate checklists were used for different quantitative study designs whereas a single checklist was developed for all qualitative studies (box 6).7,41,42,43,44 All checklists incorporated a coded comments system that allowed reviewers to record an assessment of each checklist component. After consideration of all items on a given checklist, the methodological quality of each study was rated as: ++ (all or most of the criteria have been fulfilled), + (some of the criteria have been fulfilled) or – (few or no criteria have been fulfilled).

The quality appraisal provided an indication of the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Although study‐design flaws (eg, no intention‐to‐treat analysis conducted for a randomised trial) could prompt the exclusion of quantitative evidence, in practice, none was excluded at this stage. No exclusion rules were applied to the qualitative studies as guidance is lacking on how to exclude “weak” qualitative findings. The quality scores assigned to individual studies were taken into account during the research synthesis.

Research synthesis

The first step in the synthesis process was to construct a tabular summary of all studies related to each key piece of information identified as important for inclusion in the NHSCSP letters and leaflets. An example, the evidence profile created for the colposcopy leaflet information point “Indicate that treatment can occur at the first colposcopy clinic visit”, is presented in table 1 (a summary of the study findings is also included).

Box 6 Included studies and appraisal checklists.

| Study design | Appraisal checklists |

|---|---|

| Randomised controlled trial (n = 3) | SIGN and CASP |

| Cluster randomised controlled trial (n = 1) | SIGN and CASP |

| Quasi‐randomised controlled trial (n = 3) | SIGN and CASP |

| Retrospective case control study (n = 1) | SIGN and CASP |

| Cross‐sectional study (n = 3) | SIGN and NZGG |

| Non‐comparative descriptive study (n = 7) | Reviewer checklist |

| Non‐comparative time series study (n = 1) | Reviewer checklist |

| Qualitative study (n = 13) | CASP and UKGCSRO |

Many different systems exist for grading quantitative evidence and recommendation strength,45 however, there is no agreed hierarchy of evidence in qualitative research18 or across all research methods.13 Recently, a new system of grading quantitative evidence has been proposed by an international group of experts in the field of systematic reviews (the GRADE working group).46 For the purposes of this review, a modified GRADE approach was adopted for the quantitative evidence synthesis and a similar but separate system was developed for the qualitative research.

Synthesis of quantitative evidence

The basic principles of the GRADE approach were applied to the synthesis of the quantitative evidence. The quantitative studies were tabulated for each important information point and analysed together in an evidence profile (table 1). An initial level of evidence (high, low or very low) was assigned to the group of quantitative studies reporting findings related to each information point. The initial level of evidence was then increased or decreased after consideration of the following factors: study design, quality, consistency and directness (box 7).46,49 Data on the size or magnitude of effects or associations were taken into account whenever possible—for example, if a good quality randomised trial of written information provision showed a beneficial effect on outcomes such as knowledge, understanding, acceptability or anxiety, then the kinds of information included in the trial materials were recommended. Data related to population baseline risks and resource utilisation were not available and were omitted from the review evidence profiles.

Table 1 Evidence profile for important information point in national colposcopy leaflet: “indicate that treatment can occur at the first colposcopy clinic visit”.

| Studies | Assessment | Summary of findings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Quality | Consistency * across studies | Directness † | Other factors‡ | Overall assessment | Overall recommendation | |||

| Gath, 199547 | Non‐comparative descriptive | ++ | No important inconsistency | DirectDirect | None | Very low | |||

| Olamijulo, 199730 | Non‐comparative descriptive | + | |||||||

| Howells, 199931 | Randomised trial | ++ | Uncertain | ||||||

| Definite | |||||||||

| Kuehner, 200148 | Qualitative | ++ | No important inconsistency | Direct | Close conformity based on direct evidence | High | |||

| Byrom, 200328 | Qualitative | ++ | Direct | ||||||

| Neale, 200329 | Qualitative | ++ | Direct | ||||||

• The quantitative studies indicated that the provision of a colposcopy leaflet or sheet containing information about the possibility of treatment at the first colposcopy clinic visit was acceptable to women. A need for clearer information about the possibility of receiving treatment at the initial visit was identified.

• The qualitative studies reported that women have unanswered questions about whether treatment will be received on the day of the colposcopy appointment.

*Consistency among quantitative studies refers to the similarity of estimates of effect or observations across studies.46 Consistency among qualitative studies refers to similarities in developed themes and participant experiences across studies.

†Directness refers to the extent to which people, interventions and findings are similar to the NHSCSP population.

‡Other factors include imprecise or sparse data, strong or very strong association, high risk of reporting bias, evidence of a dose‐response gradient, effect of plausible residual confounding and close conformity of findings based on direct evidence (see box 7).

Box 7 Quantitative and qualitative research evidence synthesis—assessment criteria for the level of evidence.

| 1 An initial level of evidence was assigned to a group of studies that addressed a particular information point as shown | ||

| Quantitative studies 46 | Qualitative studies | |

| High = randomised trial | High = checklist quality score “++” | |

| Low = observational study | Low = checklist quality score “+” | |

| Very low = any other evidence | Very low = checklist quality score “−“ | |

| The initial level of evidence assigned was based on the lowest hierachical type of evidence (ie, study design) in the group of studies. | The initial level of evidence assigned was based on the lowest checklist quality score of any study in the group.* | |

| *The use of the lowest checklist quality score enabled any uncertainty in the quality of the available evidence (in conduct, reporting or both) to be incorporated in the initial level of evidence assigned. | ||

| 2 The initial level of evidence was modified into one of four levels (high, medium, low and very low) according to several additional considerations | ||

| Quantitative studies46 | Qualitative studies | |

| Decrease level of evidence if: | Decrease level of evidence if: | |

| Serious (−1) or very serious (−2) limitation to study quality | ||

| Important inconsistency (−1) | Important inconsistency (−1) | |

| Some (−1) or major (−2) uncertainty about directness | Some (−1) or major (−2) uncertainty about directness | |

| Imprecise or sparse data (−1) | ||

| High probability of reporting bias (−1) | ||

| Increase level of evidence if: | Increase level of evidence if: | |

| Strong evidence of association (+1) | Close conformity of findings based on two or more studies rated as ++, directly applicable to the target population and with no major threats to validity (+1) | |

| Very strong evidence of association (+2) | ||

| Evidence of a dose response gradient (+1) | ||

| All plausible confounders would have reduced the effect (+1) | ||

Synthesis of qualitative evidence

Qualitative studies addressing one particular information point were collated and assigned an initial level of evidence (high ++, low + or very low −) on the basis of the lowest checklist quality score obtained for any study in the group (table 1, box 7). The initial level of evidence was then modified according to the consistency and directness of the evidence across the group of studies (these additional considerations acted cumulatively). As in the GRADE system, four overall qualitative levels of evidence (high, moderate, low and very low) were used during this phase of the evaluation process. Consistency referred to similarities in developed themes and participant experiences across studies whereas directness referred to the similarity between people, interventions and findings compared with the NHSCSP population. It is important to note that individual studies were not directly penalised for reporting contradictory or less direct evidence. Judgements about consistency and directness were made on the basis of the evidence provided by all of the studies, which in turn influenced the guideline recommendation for that specific information point. The existence of contradictory findings across studies was not taken to be evidence of poor quality research instead; uncertainty was reflected in the strength of the given recommendation.

For example, the qualitative studies in table 1 all indicated that women have unanswered questions about the possibility of treatment at the initial colposcopy appointment and that the studies were conducted in directly applicable populations. Therefore the initial level of evidence “high” remained unchanged. If, however, one of the three qualitative studies had received a checklist quality score of “+” instead of “++” then the initial level of evidence assigned to the group of studies would have been “low” instead of “high”. In this situation, the initial level of evidence would have been promoted from “low” to “moderate” owing to the direct and consistent findings reported by the two remaining “++” rated studies. In theory, one study could have found that women prefer to receive treatment information in‐person at the colposcopy clinic. At this point, a further decision regarding the importance of the inconsistency between studies would have been necessary. This type of grading system provides increased flexibility for reviewers when making decisions about evidence.

Recommendation system and review findings

Both overall levels of evidence (quantitative and qualitative) were used to determine which information points should be included in the screening letters and leaflets. Two categories of recommendation “definite” and “suggestive” were developed (fig 1). Items for which the quantitative and/or qualitative evidence was graded as “high” and/or “moderate” were given a “definite” recommendation for inclusion in the screening information. Items where quantitative and qualitative evidence were graded as “low” and/or “very low” were designated as “suggestive”. In this way, a final recommendation for each information point was included in the review without obscuring the contribution of each type of evidence or complicating the grading system.

Although different levels of evidence were often assigned to the quantitative and qualitative research, contradictory findings were not reported for any of the information points considered. If the qualitative research had been omitted from the review, many recommendations would not have been incorporated or achieved a “definite” status. This applied to the recommendations presented in fig 1, table 1 and the following:

The use of statements intended to reassure such as “not to worry” or “no big deal” should be avoided.

The term “wart virus” should be not be included.

The staff members participating in colposcopy and treatment appointments should be identified.

Discussion

The development of methods for the synthesis of diverse data sources in a single review is a complex challenge.14,15,34 It has been said that, “ultimately a subjective and pragmatic judgement must made about methodological issues”.23 Despite the current lack of guidance, we decided that it was still a valid exercise to attempt to pull together updated evidence‐based guidelines for the production of NHSCSP information using both quantitative and qualitative studies. The purpose of this article is to share our experiences with other researchers and contribute to the ongoing discussion about the best way forward.

The GRADE methodology has been developed46 and refined by its application to existing systematic reviews composed mainly of randomised trials.49 The reliability and sensibility of the approach is currently being assessed.49 The attraction of the GRADE system was the ability to modify the level of evidence assigned to a group of studies through consideration of factors other than study design alone. However, even with the improved flexibility of the GRADE system, study design considerations affected the level of evidence assigned to the quantitative research (it was often rated as “low” or “very low”). On the other hand, the qualitative research often obtained evidence level ratings of “high” or “moderate”. This may partly be explained by the checklist quality scores assigned to the qualitative studies and the increase in evidence level allowed by the close conformity of findings between two or more studies. A sensitivity analysis investigating the effect of the grading system on the results of the review was not attempted–further work is required on this subject.

Study quality appraisal is an important unresolved issue in the synthesis of quantitative and qualitative research.13 Many different quality criteria for the assessment of qualitative studies have been proposed but no common standards have been agreed.13,50 Controversy also exists about the defining characteristics of good quality qualitative research and the prescription of structured quality criteria.9,13,33,50 In contrast, quality checklists and formal hierarchies of evidence are included in procedural manuals for quantitative reviews of effectiveness studies.7,8

A pragmatic decision was taken to use a quality checklist modified from published sources41,44 to assess the various qualitative studies included in the review. The checklist quality score was used primarily as a means for highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of each study.9 Although checklists are convenient tools, it was often difficult to determine whether the quality of reporting or the design and execution of the study was being assessed. For some checklist criteria, the information required to make a decision about whether an item was “well covered”, “adequately addressed” or “poorly addressed” was not always available. Also, separate reviewers applied and interpreted checklist criteria in different ways (even with a coded comments system), although agreement was always reached by consensus. The quality of each study was often better captured by the detailed study assessment notes compiled during the appraisal process.

The review questions were best answered by evidence from a range of data sources. The inclusion of the qualitative research, which was often highly relevant and specific to many issues covered by the screening information, enabled the production of a set of guidelines that will directly affect policy in the NHSCSP. The updated guidelines for the content of the NHSCSP leaflets and letters appear to be sensible standards that confirm and strengthen the previous recommendations.1,28

The systematic review and synthesis of diverse research evidence, though rewarding, is challenging and time‐consuming. Several aspects of the review process that involve considerable time investment on the part of researchers include searching, study appraisal and analysis. As current methods are further developed the process should become increasingly streamlined, transparent and explicit.13,26,46 In presenting this research we hope to provide a practical example of how numerous data sources might be brought together to inform guidelines related to the contents of patient information materials.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Health Service Cervical Screening Programme and Cancer Research, UK. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of the funders.

Abbreviations

NHSCSP - National Health Service Cervical Screening Programme

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Austoker J, Davey C, Jansen C. Improving the quality of the written information sent to women about cervical screening: part 1‐evidence‐based criteria for the content of letters and leaflets; part 2‐evaluation of the content of current letters and leaflets. Sheffield, UK: NHS Cervical Screening Programme, Cancer Research Campaign, 1997No.6

- 2.Department of Health The NHS Cancer Plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: Department of Health, 20001–97.

- 3.Department of Health Choosing Health: making healthy choices easier. London: Department of Health, 20041–207.

- 4.Goldsmith M R, Bankhead C R, Austoker J. Improving the quality of the written information sent to women about cervical screening: Evidence‐based criteria for the content of letters and leaflets. NHS Cervical Screening Programmes, 2006 (NHSCSP Publication No 26),

- 5.Egger M, Davey Smith G, O'Rourke K. Rationale, potentials, and promise of systematic reviews. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, eds. Sys Rev Health Care: meta‐analysis in context London: BMJ Publishing Group, 20013–19.

- 6.Glasziou P, Vandenbroucke J P, Chalmers I. Assessing the quality of research. BMJ 200432839–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan K S, ter Riet G, Glanville J.et al, eds. Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD's guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews, 2nd edn York: York Publishing Services Ltd, NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York 2001No.4

- 8.Egger M, Davey Smith G. Principles of and procedures for systematic reviews. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, eds. Systematic reviews in health Care: meta‐analysis in context London: BMJ Publishing Group, 200123–42.

- 9.Harden A, Garcia J, Oliver S.et al Applying systematic review methods to studies of people's views: An example from public health research. J Epidemiol Community Health 200458794–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oxman A D, Cook D J, Guyatt G H. Users' guides to the medical literature. VI. How to use an overview. Evidence‐based medicine working group. JAMA 19942721367–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon‐Woods M, Bonas S, Booth A.et al How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qual Res 2006627–44. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon‐Woods M, Agarwal S, Young B.et alIntegrative approaches to qualitative and quantitative evidence. London: Health Development Agency, 20041–35.

- 13.Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy‐making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy 200510S6–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixon‐Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D.et al Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: A review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 20051045–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C.et al Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 2002121284–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eccles M, Freemantle N, Mason J. Using systematic reviews in clinical guideline development. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, eds. Systematic reviews in health care: meta‐analysis in context London: BMJ Publishing Group, 2001400–409.

- 17.Weightman A, Ellis S, Cullum A.et al Grading evidence and recommendations for public health interventions: Developing and piloting a framework. London: Health Development Agency, 20051–19.

- 18.Dixon‐Woods M, Fitzpatrick R, Roberts K. Including qualitative research in systematic reviews: opportunities and problems. J Eval Clin Pract 20017125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petticrew M, Roberts H. Evidence, hierarchies, and typologies: horses for courses. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357527–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson N, Waters E. Criteria for the systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions. Health Promot Int 200520367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giacomini M K, Cook D J. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence‐based medicine working group. JAMA 2000284357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popay J, Williams G. Qualitative Research and Evidence‐Based Healthcare. J R Soc Med 19989132–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McInnes L. To synthesise or not synthesis? That is the question! Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2005249–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ESRC Research Methods Programme [homepage on the Internet] Manchester: Economic and Social Research Council. Available from http://www.ccsr.ac.uk/methods/projects/(accessed on 11 January 2007)

- 25.Roberts K A, Dixon‐Woods M, Fitzpatrick R.et al Factors affecting uptake of childhood immunisation: a Bayesian synthesis of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Lancet 20023601596–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas J, Harden A, Oakley A.et al Integrating qualitative research with trials in systematic reviews. BMJ 20043281010–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Victora C G, Habicht J ‐ P, Bryce J. Evidence‐based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health 200494400–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byrom J, Dunn P D J, Hughes G M.et al Colposcopy information leaflets: what women want to know and when they want to receive this information. J Med Screen 200310143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neale J, Pitts M K, Dunn P D.et al An observational study of precolposcopy education sessions: what do women want to know? Health Care Women Int 200324468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olamijulo J A, Duncan I D. Patient‐based evaluation of a colposcopy information leaflet. J Obstet Gynaecol 199717394–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howells R E, Dunn P D, Isasi T.et al Is the provision of information leaflets before colposcopy beneficial? A prospective randomised study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1999106528–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw R L, Booth A, Sutton A J.et al Finding qualitative research: an evaluation of search strategies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2004;4(5). www. biomedcentral. com/1471‐2288/4/5 (accessed 11 January 2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Barbour R S, Barbour M. Evaluating and synthesizing qualitative research: the need to develop a distinctive approach. J Eval Clin Pract 20039179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones M L. Application of systematic review methods to qualitative research: practical issues. J Adv Nurs 200448271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bankhead C R, Brett J, Bukach C.et al The impact of screening on future health‐promoting behaviours and health beliefs: A systematic review. Health Technol Assess 200371–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guyatt G H, Sackett D L, Cook D J. Users' guides to the medical literature. II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence‐based medicine working group. JAMA 19932702598–2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oxman A D, Sackett D L, Guyatt G H. Users' guides to the medical literature. I. How to get started. The evidence‐based medicine working group. JAMA 19932702093–2095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Juni P, Altman D G, Egger M. Assessing the quality of randomised controlled trials. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, eds. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: meta‐analysis in context London: BMJ Publishing Group, 200187–108.

- 39.Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C.et al Evaluating meta‐ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med 200356671–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walsh D, Downe S. Meta‐synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs 200550204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) and Evidence‐based Practice [homepage on the Internet] Oxford: Public Health Resource Unit, Milton Keynes Primary Care NHS Trust; 2005 (updated Dec 2005; accessed Dec 2005) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: making sense of evidence—CASP appraisal tools. Available from, http://www.phru.nhs.uk/casp/critical_appraisal_tools.htm

- 42.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [homepage on the Internet] Edinburgh: SIGN; 2001–2005 (updated May 2004) SIGN 50: a guideline developers' handbook. Available on, http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/50/index.html (accessed 11 January, 2007)

- 43.Lethaby A, Wells S, Furness S.et alHandbook for the preparation of explicit evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines. In: Farquhar C, ed. Auckland, New Zealand: New Zealand Guidelines Group, Effective Practice Institute of the University of Auckland, 2001

- 44.Spencer L, Ritchie J, Lewis J.et alQuality in Qualitative Evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence. 2nd edn. London: Government Chief Social Researcher's Office, 2004

- 45.Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S.et al Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations I: critical appraisal of existing approaches The GRADE Working Group. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4: 38, www.biomedcentral.com/1472‐6963/4/38 (accessed 11 January 2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Atkins D, Best D, Briss P A.et al Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 20043281490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gath D H, Hallam N, Mynors‐Wallis L.et al Emotional reactions in women attending a UK colposcopy clinic. J Epidemiol Community Health 19954979–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuehner C A.The lived experience of women with abnormal Papanicolaou smears receiving care in a military health care setting [dissertation]. United States Navy Nurse Corp; Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences 2001

- 49.Atkins D, Briss P A, Eccles M.et al Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations II: pilot study of a new system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5: 25, www.biomedcentral.com/1472‐6963/5/25 (accessed 11 January 2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Dixon‐Woods M, Shaw R L, Agarwal S.et al The problem of appraising qualitative research. Qual Saf Health Care 200413223–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]