Abstract

Current knowledge about potential interactions between socioeconomic status and the short‐ and long‐term effects of air pollution on mortality was reviewed. A systematic search of the Medline database through April 2006 extracted detailed information about exposure measures, socioeconomic indicators, subjects' characteristics and principal results. Fifteen articles (time series, case‐crossover, cohort) examined short‐term effects. The variety of socioeconomic indicators studied made formal comparisons difficult. One striking fact emerged: studies using socioeconomic characteristics measured at coarser geographic resolutions (city‐ or county‐wide) found no effect modification, but those using finer geographic resolutions found mixed results, and five of six studies using individually‐measured socioeconomic characteristics found that pollution affected disadvantaged subjects more. This finding was echoed by the six studies of long‐term effects (cohorts) identified; these had substantial methodological differences, which we discuss extensively. Current evidence does not yet justify a definitive conclusion that socioeconomic characteristics modify the effects of air pollution on mortality. Nevertheless, existing results, most tending to show greater effects among the more deprived, emphasise the importance of continuing to investigate this topic.

Keywords: air pollution, mortality, effect modifier, socioeconomic factors, urban health

An inverse gradient between socioeconomic status (SES) and mortality in Western countries has been solidly established.1 This gradient is well documented for all‐cause mortality as well as for some specific causes of death, including cardiovascular diseases2,3,4 and several cancers.4,5,6 Although most pronounced during middle age, it is also observed among the elderly.7

The prevalence of numerous risk factors for potentially fatal diseases (again, cardiovascular diseases and cancers) also tends to be inversely associated with SES. Compared with populations with high SES, less advantaged populations tend to smoke more8 and to eat less fresh fruit and vegetables9 and more saturated fat.10 They also face more types of psychosocial stress (eg, financial strain, job insecurity, low control at work)11 and receive poorer healthcare (accessibility, use, quality of care).12 Nonetheless, it remains difficult to quantify the extent to which the unequal distribution of these risk factors in populations with divergent SES explains these socioeconomic mortality gradients.

Moreover, relatively few studies have examined the contribution of environmental exposures, such as air pollution, to socioeconomic health inequalities.13 Several authors hypothesise that air pollution contributes to creating or accentuating the socioeconomic disparities seen in various diseases (including cancer,14 asthma15 and cardiovascular diseases16) and thus in premature death rates.17 Two types of potential mechanisms have been suggested.

Firstly, populations with low SES may be more frequently or more intensely exposed to air pollution than those with high SES.18,19 Nonetheless, Bowen concluded in 2002 that the results of studies documenting the distribution of exposure to air pollution in populations with different SES remain “mixed and inconclusive”.20 Later studies21,22,23,24 support this observation. The methodological diversity of these studies and the variety of their settings22 may partly explain the heterogeneity of their results.

Secondly, populations with low SES may be more susceptible to air pollution than those with high SES18 in that several factors which are more prevalent in less advantaged populations may be effect modifiers of the relationship between pollution and mortality. These include poor health status (for example, diabetes, obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease),18 addictions (including smoking)25 and multiple pollutant exposures (passive smoking, occupational exposure) likely to act in addition to or in synergy with urban pollution,25 and difficulties with access to healthcare.19,26 Less obvious factors, such as psychosocial stress,17,19,26 low intake of proteins, vitamins and minerals,19 and even genetic make‐up17 may also play a part.

This review examines studies that tested this second hypothesis about mortality, by asking if SES is a sensitivity factor in the relationship between atmospheric pollution and mortality.

Methods

We searched Medline from its inception to the end of April 2006, using three‐MeSH term queries following the structure “Mortality AND Socioeconomic Factors AND Air Pollution”. The following alternative MeSH terms were also used: “Death” for mortality; “Social Class, Unemployment, Income, Poverty, Educational Status, Education, Occupations” for socioeconomic factors; and “Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulphur Dioxide, Carbon Monoxide” for air pollution.

Non‐MeSH terms also used included “Socioeconomic Status”, “SES”, “Wealth” “Insurance Status” “Poverty” “Deprivation” and “Particulate Matter”. Studies were identified either because their abstract explicitly mentioned testing effect modification by socioeconomic indicators, or because they were cited in retrieved articles. Two unpublished studies27,28 were identified in this way, and detailed information was then obtained from the authors.

Cross‐sectional studies, considered to provide weaker evidence than other study designs, were excluded from the study report. We finally identified 21 studies.

Results

We first present those studies that tested the influence of socioeconomic variables on the short‐term (0–3 days) relationship between air pollution and mortality and then those studies that examined the influence of socioeconomic variables on the long‐term (several years) relationship. Because the associations observed between mortality and exposure to air pollution are likely to be sensitive to how air pollution exposure is measured (ecological measurements at different geographic resolutions, individual measurements, time resolution of the measurement, lag time for health effects), we report in detail the exposure measures used in each study.

SES is often a confounder in studies of long‐term pollution health effects.29,30 It is also a multidimensional notion that no single socioeconomic variable (education, occupation, assets, income), considered alone, can capture.31 No socioeconomic variable can serve as another's proxy.31 Accordingly, we also report the details of the socioeconomic variables used in each study.

Careful examination of these factors showed that the studies identified were too heterogeneous in their exposure measurements, socioeconomic indicators and subjects' ages for meta‐analysis.

Studies of short‐term relationships

Ten time‐series studies (table 1), four case‐crossover studies and one cohort study (table 2) of the short‐term relationship between pollution and mortality were identified.

Table 1 Time‐series studies of short‐term relationships between air pollution and mortality.

| Author | Population | Health variables (number of cases) | Exposure variables (time resolution, spatial resolution) | SES variables (resolution) | Method of evaluation of effect modification | Lags tested (days) | Principal results (95% confidence interval when available) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samet et al36 | Residents of 20 US cities, all ages, 50 000 000 inhabitants, 1987–1994 | Non‐trauma mortality (3 000 000), cardio‐ vascular and respiratory mortality (1 600 000) | PM10 adjusted for O3, SO2, NO2, CO (daily mean, city) | % High school graduates % Annual income <US$12 675 % Annual income >US$100 000 (city) | Hierarchical bayesian model: First level, log‐ linear regression of mortality rate according to pollutants and confounders in each city Second level, linear regression of pollutant effects in all cities according to SES characteristics | 1 | PM10 ‐ mortality associations in cities not associated with city SES characteristics (95% posterior interval for these SES variables, all include 0*) |

| Schwartz38 | Residents of 10 US cities, all ages, 14 000 000 inhabitants, 1986–1993 | Non‐trauma mortality (1 100 000) | PM10 (mean: day of death and preceding day, city) excluding days where it exceeded 150 μg.m−3 | Unemployment rate % Population below poverty level % Population with a college degree (city) | Hierarchical model meta‐regression Measurement of the variation of the effect of PM10 for a 5% increase in the SES variable | 0 | No modifying effect Results in graphic form Variation of effects of PM on mortality for a 5% increase in the SES variables: % poverty 0 (−0.05; 0.05) % college degree 0 (−0.03; 0.03) unemployment rate 0.02 (−0.06–0.1) |

| O'Neill et al39 | Residents of Mexico City, >65 years, 20 000 000 inhabitants, 1996–1998 | Non‐trauma mortality (206 510) | PM10, O3 (mean: day of death and preceding day, city) | Sociospatial development index (3 classes) % Homes with electricity % Homes with piped water % Homes with drainage % Literacy % Indigenous language speakers (county) | Stratified analysis | 0 | PM10 not associated with mortalityO3: Sociospatial development index High/medium high 2.76 (1.14; 4.40) Medium/medium low 0.64 (−0.44; 1.72) Low/very low 3.78 (0.76; 6.89) % Homes with electricity >99.8, 1.63 (0.50; 2.78) 93–99.8, 0.92 (−0.93; 2.81) 82–93, 1.50 (−0.94; 4.00) 60–82, 2.04 (−0.64; 4.80) % Homes with piped water >99.6, 2.09 (0.56; 3.65) 75–99.6, 0.78 (−0.85; 2.44) 35–75, 1.58 (−0.28; 3.48) 21–35, 1.79 (−0.03; 3.64) % Homes with drainage >99.3, 1.45 (−0.07; 3.01) 80–99.3, 1.47 (−0.22; 3.18) 45–80, 1.54 (−0.29; 3.40) 21–45, 1.88 (0.14; 3.66) % Literacy >97.5, 2.89 (1.34; 4.46) 96–97.5, 0.43 (−1.15; 2.04) 88–96, 0.92 (−1.09; 2.97) 80–88, 1.59 (−0.16; 3.36) % Indigenous language speakers 0.3–1, 1.58 (−0.25; 3.44) 1–1.5, 1.20 (−0.26; 2.69) 1.5–2, 3.54 (1.56; 5.57) 2–6, 0.59 (−1.34; 2.55) 6–10.4, 1.18 (−1.52; 3.96) |

| Martins et al32 | Residents of six zones of Sao Paulo (Brazil), >60 years, 992 018 inhabitants, 1997–1999 | Respiratory mortality (1991) | PM10 (3‐day moving average, city subdivision (called regions) included in 2‐km radius around traffic pollution monitors) | % People with college education % Families with monthly income >US$3500 % People living in slums (city subdivisions) | Spearman rank correlations between associations of PM10 with respiratory mortality and SES variables | 0 | Effect of PM10 on respiratory mortality: negatively correlated with: % college education (−0.94, p<0.01) % family income >US$3500 (−0.94, p<0.01) positively correlated with % people living in slums (0.71, “not significant”*) |

| Gouveia and Fletcher40 | Residents of Sao Paulo (Brazil), >65 years, 9 500 000 inhabitants, 1991–1993 | Non‐trauma mortality (151 756) | PM10 (daily mean, city) | Composite index (4 classes) (58 districts in Sao Paulo) | Stratified analysis then interaction term in a model Significance of interaction tested by log‐ likelihood ratio test | 0, 1 and 2 | Results in graphic form Relative risks slightly stronger in more advantaged neighbourhoods (but p>0.50*) |

| Jerrett et al26 | Residents of Hamilton (Canada), all ages, 320 000 inhabitants, 1985–1994 | Non‐trauma mortality (27 458) | CoH, SO2, (reciprocal adjustments for these pollutants) (concentrations averaged for 1–3 days before death, 5 city subdivisions) | Mean household income % Unemployment % Poverty % HS or less % <grade 9 % Manufacturing employment (5 city subdivisions) | Stratified analysis 1) Maximum likelihood random effects model (evaluation of differences between relative risks of city subdivisions and relative risk for the entire city) 2) Regression of mean % change in mortality associated with exposure for SES characteristics in each area | 0–3 | Overall, stronger and more significant relative risks and in zones with unfavourable SES characteristics 1) Random effects model: no significant differences in relative risks between zone and entire city 2) Manufacturing employment and educational level significantly correlated with the effect of CoH on mortality (p value not given)* |

| Cifuentes et al28 | Residents of Santiago (Chile), 25–64 years, 5 000 000 inhabitants, 1988–1996 | Non‐trauma mortality (43 400) | PM2.5, CO (reciprocal adjustments) (mean: day of death+preceding day, city) | Educational attainment: ‐no education ‐elementary school ‐HS ‐university (individual) | Stratified analysis | 0 | PM2.5 After stratification, relative risks were significant (or very nearly so) only in the group with elementary education CO After stratification, no significant relative risk |

| Villeneuve et al34 | Vancouver (Canada) residents in British Columbia Health datasets, >65 years, 550 000 subjects, 1986–1999 | Non‐trauma mortality (93 612) Cardio‐ vascular mortality (40 840) Respiratory mortality (11 650) | TSP, CO, NO2, SO2, O3, PM10, PM2.5 (mean concentrations for the 3 days before death, city) | Mean family income (3 classes) (enumeration area) | Stratified analysis | 0 | Results in graphic form After stratification, the only statistically significant relative risks concerned non‐trauma mortality: ‐NO2 in low and middle income ‐SO2 in low income (borderline significance) ‐TSP in high and low income |

| Zanobetti and Schwartz41 | Residents of Chicago, Detroit, Minneapolis‐ St Paul and Pittsburgh (USA), all ages, 10 000 000 inhabitants, 1986–1993 | Non‐trauma mortality (782 502) | PM10 (mean: day of death +preceding day, city), excluded days where it exceeded 150 μg.m−3 | Educational attainment: <HS ⩾HS (individual) | Stratified analysis | 0 | % Increase in death for 10 μg.m−3 increase in PM10 <HS 0.92 (0.66–1.18) ⩾HS 0.71 (0.19–1.23) Difference judged not statistically significant (because of overlapping confidence intervals) |

| Wojtyniak et al27 | Residents of Cracow, Lodz, Poznan and Wroclaw (Poland), 0–70 years or >70 years, 2 000 000 inhabitants, 1990–1996 | Non‐trauma mortality (unknown) Cardio‐ vascular mortality (unknown) | BS, NO2 and SO2 (mean: day of death+ preceding day, city) | Educational attainment: ‐below secondary (primary and vocational) ‐secondary and above (post secondary and university) (individual) | Stratified analysis | 0–1 | Non‐trauma mortality BS: significant effects only for less than secondary education (< and ⩾70 years) NO2: significant in ⩾70 years regard‐ less of education: in ⩾70 years for below secondary education only SO2: significant effects only in those ⩾70 years with less than a secondary education Cardiovascular mortality BS: significant effects only for those with less than a secondary education (< and ⩾70 years) NO2: in <70 years, significant for secondary education and above only (similar but not significant for below secondary education) In ⩾70 years, significant regardless of education (but larger in lower education) SO2: significant effects only for those ⩾70 years with below secondary education |

*No further details available.

BS, black smoke; CO, carbon monoxide; CoH, coefficient of haze; HS, high school; NO2, nitrogen dioxide; O3, ozone; PM, particulate matter; PM10, particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of up to 10 μm; PM2.5, particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of up to 2.5 μm; SO2, sulfur dioxide; TSP, total suspended particulates.

Table 2 Case‐crossover and cohort studies of short‐term relationships between air pollution and mortality.

| Author | Population | Health variable (number of cases) | Exposure variables (time resolution, space resolution) | SES variables (resolution) | Method to evaluate effect modification | Lags tested (days) | Principal results (95% confidence interval when available) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bateson and Schwartz42 | Residents of Cook County (IL, USA), >65 years and previously hospitalised for cardiac or pulmonary diagnosis, 1988–1991 | All‐cause mortality (65 180) | PM10 (mean: day of death+preceding day, county) | ‐Median house‐ hold income ‐% Adults with bachelor's degree ‐% Adults not speaking English at home (ZIP code of residence) | Ratio of log of OR (pollution/mortality) of the population with a given SES characteristic to the log of the OR of 1 for the population with‐ out this characteristic Linear continuous interaction terms between PM10 and SES variables in the model | 0 | No significant modifying effect Increase in mortality for a 10 μg.m−3 increment in PM10 concentration ‐increase of 0.2% (−0.28%; 0.67%) for an increase of 10% in bachelor's degrees ‐increase of 0.002% (−0.393%; 0.399%) for an increase of 10% in adults not speaking English at home ‐decrease of 0.04% (−0.65; 0.55) for an increase of US$10 000 in median household income |

| Zeka et al35 | Residents of 20 US cities, all ages, 1989–2000 | Non‐trauma mortality (1 896 306), respiratory mortality (190 000), mortality from cardiac disease (625 800), mortality from infarction (493 000), mortality from stroke (132 700) | PM10 (mean: day of death+2 preceding days; city) | Educational attainment: <8 years of schooling 8–12 years of schooling ⩾13 years of schooling (individual) | Stratified analysis Trend tests | 0 | Increase in mortality for a 10 μg.m−3 increment in PM10 concentration Non‐trauma mortality <8 years of schooling 0.62 (0.29; 0.95) 8–12 years of schooling 0.36 (0.12; 0.60) >12 years of schooling 0.27 (−0.004; 0.54) (trend not significant, p = 0.29) Respiratory mortality <8 years of schooling 0.82 (−0.32; 1.96) 8–12 years of schooling 0.88 (0.12; 1.64) >12 years of schooling 0.88 (−0.04; 1.80) Mortality by cardiac disease <8 years of schooling 0.72 (0.23; 1.21) 8–12 years of schooling 0.38 (0.07; 0.69) >12 years of schooling 0.54 (0.13; 0.95) Mortality by infarction <8 years of schooling 0.33 (−0.83; 1.49) 8–12 years of schooling 0.79 (0.28; 1.30) >12 years of schooling 0.13 (−0.82; 0.56) Mortality by stroke <8 years of schooling 0.07 (−1.44; 1.58) 8–12 years of schooling 0.29 (−0.32; 0.90) >12 years of schooling 0.52 (−0.28; 1.32) |

| Filleul et al37 | Residents of Bordeaux (France), >65 years, 1988–1997 | Non‐trauma mortality (527), cardio‐ respiratory mortality (197) | BS (daily mean, city) | Educational attainment: ‐without primary school diploma ‐primary school diploma ‐secondary validated or higher Previous occupation ‐never worked ‐white‐collar ‐blue‐collar (individual) | Stratified analysis | 3 | Increase in mortality for a 10 μg.m−3 increment in BS concentration Non‐trauma mortality: only subgroup with significant OR: blue collar OR = 1.41 (1.05–1.90) Cardiorespiratory mortality: only subgroup with significant OR: +high educational level OR = 4.36 (1.15–16.54) |

| Filleul et al43 | Residents of Bordeaux (France), >65 years, 1988–1997 | Non‐trauma mortality (543) | BS (above 90th percentile or below 10th percentile of observed concentrations) (daily mean, city) Adjustments for age, sex, smoking habits and education (or occupation) | Educational level: ‐no school ‐primary without diploma ‐primary with diploma Previous occupation: ‐domestic employees and women at home ‐blue‐collar workers ‐craftsmen and shopkeepers ‐other employees, intellectual occupations (individual) | Stratified analysis | 0 | No modifying effect apparent |

| Romieu33 | Children in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, aged 1 month to 1 year, 1997–2001 | Total mortality (628), respiratory mortality (216) | PM10,O3 (mean for the 8 h of highest concentrations) (averaged on 1, 2 or 3 days before death, city) model with these 2 pollutants | Composite SES index (3 levels) (ZIP code of residence) | 1) Global analysis with introduction of an interaction term for SES 2) Stratified analysis | 1 and 2 | 1) Global analysis: no significant association between pollutants and mortality, but “marginally significant” interaction between SES and PM10 (p = 0.10) 2) Stratified analysis: for respiratory mortality, only the children with the lowest SES present statistically significant or almost significant OR for PM10 Averaged concentrations for 1 day, lag 1: OR = 1.61 (0.97; 2.66) Concentrations averaged for the 2 days before death: OR = 2.56 (1.06; 6.17) No statistically significant association with O3 |

BS, black smoke; HS, high school; O3, ozone; PM10, particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of up to 10 μm.

Most estimated pollutant concentrations at the resolution of a city or county. Only two authors estimated concentrations at finer geographical resolutions. Jerrett et al divided Hamilton (Canada) into five zones based on Thiessen polygons (approximately 2×3 km to 8×7 km), defined around pollution monitors as the central nodal points.26 In Sao Paulo (Brazil), Martins et al defined six subcity zones within a 2‐mile (3.2‐km) perimeter around monitors, all of which were at sites of high traffic.32 In both cases, the pollutant concentrations attributed to each defined zone were those measured by the monitors in that zone.

All but three28,32,33 of the studies identified examined non‐trauma all‐cause mortality in subjects aged 65 years and older or in subjects of all ages. As relatively few results were available for specific causes of death (respiratory,32,34,35 cardiovascular27,34,35 and cardiorespiratory36,37), we report and discuss only those results dealing with all‐cause mortality.

Mortality for those 65 years or older.

Four studies examined PM10 (particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of up to 10 μm). In Mexico City (Mexico), O'Neill et al39 tested the influence of percentage of literate subjects, percentage of indigenous language speakers, percentage of homes with electricity, piped water or drainage, and a sociospatial development index, all measured at the resolution of a county. In Vancouver (Canada), Villeneuve et al34 tested the influence of mean family income, measured by “enumeration areas”. In Cook County, IL (USA), Bateson and Schwartz examined the influence of percentage with bachelor's degrees, median household income and percentage of adults not speaking English at home, measured by ZIP codes.42 None of these studies showed any effect modification by the socioeconomic variables tested. In Sao Paulo (Brazil), Gouveia and Fletcher reported stronger associations for the populations with higher SES, measured by a composite deprivation index at a district resolution,40 but the differences in the associations observed according to the value of the deprivation index were not statistically significant.

Three studies examined black smoke and individual socioeconomic variables. In four Polish cities, Wojtyniak et al observed statistically significant associations only in subjects who had not completed secondary school.27 In their case‐crossover study in Bordeaux (France), Filleul et al observed statistically significant associations only in subjects who were blue‐collar workers, but found no statistically significant association when the study population was stratified according to educational level.37 In a cohort study of the same population, which compared the characteristics of people who died on days when the highest and lowest black smoke concentrations were observed (that is, above the 90th and below the 10th percentile of observed concentrations), Filleul et al found that neither past occupational status nor educational level modified the effect of pollution on mortality.43

Villeneuve et al found no modification by mean family income, assessed by enumeration area, of the effect of either total suspended particulates (TSP) or PM2.5.34 Both Villeneuve et al34 and O'Neill et al39 studied ozone and found no modifying effect by any of the SES variables tested.

All‐age mortality

Four studies examined PM10. In a study of 20 US cities, Samet et al found that the effect of PM10 was not modified by the percentage of high school graduates or by either of two income indicators (percentage with annual income <US$12 675, percentage with annual income >US$100 000), all measured city‐wide.36 Similarly, Schwartz studied 10 US cities and found no effect modification by unemployment rate, percentage of the population below the poverty line or percentage of college degrees, all measured city‐wide.38 In a study of four US cities, Zanobetti and Schwartz used individual data about educational level41 and found stronger associations for the subjects who had not completed high school (interaction not statistically significant). A study by Zeka et al of 20 US cities also used individual data and showed associations twice as strong for the subjects who had not attained high school as for those who went on to college. The trend was nonetheless not statistically significant.35

In Hamilton (Canada), Jerrett et al observed stronger associations (statistically significant interaction) for the coefficient of haze (CoH) in zones with more manufacturing employment and lower educational levels. There were no statistically significant interactions with the other SES variables tested (table 1).26

For black smoke, Wojtyniak et al reported statistically significant associations only for subjects who had not completed secondary school.27

Studies of long‐term relationships

Six cohort studies (table 3) tested the influence of socioeconomic variables on long‐term relationships between pollution and mortality.

Table 3 Studies of long‐term relationships between air pollution and mortality.

| Author | Population | Health variable (number of cases) | Exposure variables (resolution) | Adjustment variables | SES variables (resolution) | Method of evaluation of effect modification | Relative risks (95% confidence intervals) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krewski et al44 | 8111 subjects of the Six Cities cohort, 25–74 years at enrollment, follow‐up: 1974–1991 | Non‐trauma mortality (1430) Cardio‐ pulmonary mortality (unknown) | PM2.5, Sulfates (city) | Active and passive smoking, BMI, alcohol consumption, occupational exposures to dust and fumes | Educational attainment: <HS HS >HS (individual) | Stratified analysis | All‐cause mortality (PM2.5) <HS 1.45 (1.13 to 1.85) HS 1.30 (0.98 to 1.73) >HS 0.97 (0.71 to 1.34) Cardiopulmonary mortality (PM2.5) <HS 1.28 (0.92 to 1.77) HS 1.42 (0.98 to 2.08) >HS 1.40 (0.88 to 8.23) All‐cause mortality (sulfates) <HS 1.47 (1.14 to 1.89) >HS 0.99 (0.72 to 1.36) Cardiopulmonary mortality (sulfates) <HS 1.28 (0.91 to 1.79) >HS 1.47 (0.90 to 2.24) |

| Krewski et al44 | Subjects of the American Cancer Society (ACS) cohort, ⩾30 years at enrollment, follow‐up: 1982–1989; 295 223 subjects for the PM2.5 cohort; 552 138 subjects for the sulfate cohort | Non‐trauma mortality (20 765) Cardio‐ pulmonary mortality (unknown) | PM2.5, Sulfates (city) | Active and passive smoking, BMI, alcohol consumption, occupational exposures to dust and fumes | Educational attainment: <HS HS >HS (individual) | Stratified analysis | All‐cause mortality (PM2.5)<HS 1.35 (1.17 to 1.56)HS 1.23 (1.07 to 1.40)>HS 1.06 (0.95 to 1.17)<HS 1.47 (1.21 to 1.78)HS 1.35 (1.11 to 1.64)>HS 1.14 (0.98 to 1.34)All‐cause mortality (sulfates)<HS 1.27 (1.13 to 1.42)>HS 1.05 (0.96 to 1.14)Cardiopulmonary mortality (sulfates)<HS 1.39 (1.20 to 1.62)>HS 1.11 (0.98 to 1.25) |

| Filleul et al45 | 14 284 Residents of 7 French cities, 25–59 years at enrollment, follow‐up: 1974–2000, living in one of 21 defined city sub‐ divisions, excluding manual workers | Non‐trauma mortality (2396) | BS, TSP, NO2 (18 city subdivisions: 0.5–2.3 km in diameter) | Active smoking, smoking status of partner, BMI, occupational exposures to dust, gas and fumes | Educational attainment: ‐primary ‐secondary ‐university (individual) | Stratified analysis | Results in graphic form No trend as a function of educational level for any of the 3 pollutants |

| Hoek et al46 | 4492 Dutch NLCS cohort subjects, 55–69 years at enrollment, follow‐up: 1986–1994 | Non‐trauma mortality (489) | BS, 3‐component measurement (regional background, urban background and proximity to major roads) (residence address) | Active smoking, smoking status of partner, last occupation (not codable, never paid work, blue collar, upper white collar, other), alcohol intake, BMI (Quetelet index), total fat intake, vegetable and fruit consumption | Educational attainment ‐primary school ‐basic vocational education ‐⩾HS (individual) | Stratified analysis | Primary school 1.62 (0.97 to 2.70), lower vocational education 1.24 (0.79 to 1.94), ⩾HS 1.16 (0.64 to 2.10) Differences not statistically significant (p = 0.434 for medium vs low and p = 0.403 for high vs low |

| Finkelstein et al47 | 5228 residents of Hamilton‐ Burlington, (Canada) >40 years who had a lung function test follow‐up: 1992–2001 | Non‐trauma mortality (604) | TSP, SO2 (means for 3 years transposed to entire study period) above or below the median concentrations measured (41 μg.m−3 for TSP and 4.6 ppb for SO2) (residence address) | BMI, lung function (FEV1, FVC), chronic pulmonary diseases, chronic ischaemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus | Mean household income (above or below median for the area study) (enumeration area) | Stratified analysis | Relative risks higher for the low household income category: for TSP low household income 1.14 (1.07 to 1.20) high household income 1.04 (1.01 to 1.06) for SO2 low household income 1.18 (1.11 to 1.26) high household income 1.03 (0.83 to 1.28) |

| Finkelstein et al16 | 5228 residents of Hamilton‐ Burlington, (Canada) >40 years who had a lung function test follow‐up: 1992–2001 | Cardio‐ vascular mortality (252) | Pollution index (sum of standardised values of SO2 and TSP concentrations) (residence address) ‐ Traffic proximity (major urban road <50 m or highway <150 m) (residence address) | BMI, lung function (FEV1, FVC), chronic pulmonary diseases, chronic ischaemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus | Deprivation index (composite) DI = −0.66*log (income)+0.55* unemployment rate+0.51*% of residents who did not complete high school) (enumeration area) | Introduction of deprivation index as interaction term | No statistically significant interaction for pollution index or traffic proximity (data not shown by authors) |

BMI, body mass index; BS, black smoke; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; HS, high school; NO2 nitrogen dioxide; PM2.5, particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of up to 2.5 μm; SO2, sulfur dioxide; TSP, total suspended particulates.

The reanalysis of cohorts from the Six Cities Study (8111 subjects aged 25–74 years at recruitment, followed from 1974 through 1991)48 and the American Cancer Society (552 138 subjects aged 30 years or more at recruitment, followed from 1982 through 1989)49 tested the influence of subjects' educational levels on the relationships between exposure to air pollutants (PM2.5 and sulfates) and mortality in 56 US cities. Pollutant concentrations were estimated city‐wide. PM2.5 measurements were not available for the entire ACS cohort (only for 295 223 subjects). Several individual covariates were taken into account: direct and indirect smoking, occupational exposure to dust or fumes, body mass index (BMI) and alcohol consumption.44 For all‐cause mortality, subjects who had not completed high school had stronger (and statistically significant) relative risks for PM2.5 than those who continued on to college (relative risks not statistically significant). A similar but less pronounced result was observed for cardiopulmonary mortality. Results were generally similar for sulfates. Follow‐up of the ACS cohort, prolonged through 1998 and including additional covariates (fat intake, consumption of vegetables, citrus, high‐fibre grains), confirmed these observations.50

In the PAARC study of seven French cities (14 284 subjects aged 25–59 years at recruitment and followed from 1974 through 2000), Filleul et al tested the influence of educational level on the relationship between mortality and exposure to black smoke, TSP and NO2.45 Pollutant concentrations were measured by monitors set up especially for this study in 24 residential areas 0.5–2.3 km in diameter. The covariates considered were smoking (by subjects and their spouses), BMI and occupational exposure to dust, gas and fumes (estimated dichotomously via a job exposure matrix). Manual labourers were excluded from this study. After the exclusion of six zones whose measurements were judged to be excessively influenced by main roads near the monitors, no gradient according to educational level (primary, secondary or university) was found for the associations between all‐cause mortality and any of the three pollutants.

In the Netherlands, Hoek et al tested the influence of educational level on the relationships between black smoke and mortality in the NLCS cohort (4492 subjects aged 55–69 years at recruitment, followed from 1986 to 1994).46 They used a three‐component exposure measure that combined regional background (estimated by inverse distance squared weighted interpolation of regional background monitoring station measurements), additional urban background (estimated by regression analyses of the density of postal addresses and monitoring station measurements) and the influence of roadways near the subjects' homes (<50 m for local roads, <100 m for major roads). Observed air pollution levels were lower among less educated subjects. The covariates studied were smoking (by subject and spouse), BMI (Quetelet index), fruit and vegetable consumption and total fat intake. The relative risk between black smoke and mortality was higher for subjects with only elementary school education than for those with intermediate vocational education. The relative risk for subjects with intermediate vocational education was itself higher than that for subjects who had at least completed high school. The differences in relative risks were not, however, statistically significant.

In Hamilton (Canada), Finkelstein et al tested the influence of mean household income of the neighbourhood (enumeration area) on the relationships between TSP, SO2 and mortality.47 The cohort included 5228 subjects greater than 40 years of age at recruitment, who had been referred for pulmonary function testing and were followed from 1992 through 1999. The concentrations of these pollutants were estimated at the resolution of residences (postal address) by universal kriging of measurements from monitors (29 monitors for TSP, 19 for SO2). This study used a dichotomous exposure measure (above or below the median of the concentrations estimated for the study area). The covariates studied were BMI, chronic disease diagnoses (chronic pulmonary diseases, chronic ischaemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus) and lung function measures. Since no smoking data were available, the authors assumed that lung function was a proxy for smoking status. The relative risks of mortality associated with TSP and SO2 were higher for subjects living in enumeration areas with a mean household income less than the Hamilton median.

Finkelstein et al replicated this study with the same pollution data and the same population, focusing specifically on mortality from cardiovascular causes.16 SES was estimated using a composite deprivation indicator (table 3), assessed at the resolution of an enumeration area. Two pollution indicators were estimated for each subject's actual residence address: a background pollution index (sum of the standardised values of TSP and SO2) and a measure of proximity to roads (subjects considered exposed if they lived less than 50 m from a major urban road or less than 100 m from a highway). The deprivation indicator did not modify the associations between cardiovascular mortality and either of these two exposure measures.

Discussion

Studies of short‐term relationships

All but one26 of the studies examining all‐cause mortality used city‐wide exposure measurements. They considered diverse pollutants, most often PM10.34,35,36,38,39,40,41,42 Given the very strong correlations between PM2.5 and PM10 reported by two studies of PM2.5 (0.83 for Villeneuve et al,34 0.96 for Cifuentes et al28), their results may also be related to PM10. None of the studies examined here provided information about correlation of black smoke, TSP and CoH with PM10, but earlier studies have shown that black smoke and TSP are often strongly correlated with PM10.51,52 Similar correlations for CoH and PM10 are less clear. Very few studies adjust for copollutants.26,28,36 The temporal resolution of exposure measurements (a day,43 mean of several days34) and delayed effects (lags) tested also differs slightly between studies.

These studies use socioeconomic variables that are very diverse in both in their nature (eg, educational level, income, percentage of unemployed people in the neighbourhood, composite deprivation index) and their resolution (individuals,37 cities,36 districts,40 author‐defined city subdivisions,26,32 enumeration areas,34 and ZIP codes33). Moreover, for the same type of socioeconomic variable, different studies sometimes use different cut‐off points for defining deprivation (tables 1 and 2).

All these differences make it difficult to summarise results from the available studies (eg, by meta‐analysis) and to draw solid conclusions. Nonetheless, one point is striking: of the three studies that used socioeconomic variables at very coarse geographic resolutions (city‐wide or county‐wide), none found differences in associations according to these socioeconomic variables, despite very large populations. The studies using socioeconomic variables at finer geographic resolutions produced mixed results. And above all, five of the six studies that used individual socioeconomic variables (educational level27,28,35,37,41,43 or occupation43) reported stronger pollution–mortality associations for the populations with the more unfavourable socioeconomic variables.

This observation does not justify a definitive conclusion that SES interacts with the short‐term relationship between pollution and mortality, but it does highlight the importance of continuing to study the influence of socioeconomic variables (in particular individual variables) on this relationship.

Studies of long‐term relationships

Studies focusing on long‐term relationships generally encounter greater difficulties than those examining short‐term relationships in documenting subjects' precise exposures and in eliminating the influence of confounding factors (whereas in studies of short‐term relationships, factors that remain stable during the lag period between exposure and event are not confounding factors).

In all these studies, exposure was assessed when subjects entered the cohort. The authors assumed that those measurements were reasonable approximations of exposure for the years before and after study entry. On a city‐wide scale, mean annual pollutant concentrations are generally stable from one year to the next. Substantial changes in concentrations occur over decades rather than years. It therefore seems reasonable to assume that this approximation resulted in little exposure misclassification.46

Another potential problem associated with long‐term exposure measurements is people's mobility. In the Six Cities Study, the difference in relative risk according to educational level was observed both for subjects who had changed city of residence during the follow‐up period and for those who had not. The ACS cohort data, unfortunately, could not test this relationship.44 Hoek et al, Finkelstein et al and Filleul et al did not take into account their subjects' changes of residence after study entry.16,45,46,47 Hoek et al justified this decision by pointing out that 90% of subjects had lived at their 1986 address for 10 years or more. Moreover, they did test relationships with black smoke and found relative risks (all education levels) were similar for the subjects who had lived for 10 years or more at their 1986 address and for the entire cohort.46 Accordingly, it appears implausible that changes in residence of members of the ACS, Six Cities and NLCS cohorts might explain the differences in relative risks observed according to educational level. This possibility cannot be ruled out for the Hamilton cohort,16,47 however, since the authors had no information about subjects changing accommodation. This is also the case for the PAARC cohort, where only 23.4% of the subjects lived in the same area during recruitment and 25 years later.45

Dockery and Pope et al presented city‐wide measurements as an acceptable proxy for assessing residents' long‐term exposure to PM2.5.48,49 Finkelstein, however, considered that intra‐urban variations in outdoor PM2.5 concentrations could cause differential exposure misclassification that might explain the differences in the relative risks observed according to educational level.53 Findings by Jerrett et al in Los Angeles54 and Rotko et al in Helsinki55 support this hypothesis. To avoid this potential problem, the NLCS, PAARC and Hamilton cohorts used intra‐urban level exposure measurements.16,45,46,47

Several types of factors which are unequally distributed between populations with different SES may be effect modifiers of the relationship between pollution and mortality. In some cases, this might explain the variation in pollution–mortality associations observed between groups with different SES. The influence of some of these factors on the relationship between pollution and mortality were tested in some cohorts:

Smoking was considered in all cohorts, except that in Hamilton. In the Six Cities, ACS and NCLS cohorts, smoking was not an interaction factor between pollution and mortality.44,46 Nonetheless, when the ACS cohort was followed through 1998,50 relative risks associated with PM2.5 became stronger in non‐smokers (since the cohort had aged, a healthy smoker effect may be suspected). In contrast, the relative risks associated with pollution in the PAARC study were stronger in smokers than in non‐smokers.

Occupational exposure to dust, gas and fumes was considered only in the Six Cities, ACS and PAARC cohorts. In the first two, these exposures did not notably modify the relative risks observed between PM2.5 and mortality.44 In the PAARC study (not including manual labourers), subjects with these occupational exposures had higher pollution‐related relative risks.

When they were considered, passive smoking,44 spouse's smoking status45,46 and diet46,50 did not substantially modify the associations between pollution and mortality.

No clear lessons can be drawn from the examination of these factors: smoking and occupational exposures do not seem to be effect modifiers except in the PAARC study, where the associations observed between pollution and mortality did not differ noticeably according to educational level.45 In contrast, in the studies where the associations observed between pollution and mortality differed substantially according to the value of the SES indicators,44,46 no covariate appeared to be a sufficiently important effect modifier to explain these differences.

These six studies do not allow us to reach any definitive conclusions about the modifying effects of SES variables on the long‐term relationships between pollution and mortality. It is nonetheless interesting that four of them showed associations that differed clearly in extent according to individual education level44,46,50 and neighbourhood household income.47 Nonetheless we cannot totally rule out the possibility of confounding factors that were measured poorly or not at all (indoor pollution, occupational exposure) or of differential exposure misclassification according to SES.

Problems common to short‐ and long‐term studies

In an attempt to overcome this problem of potential differential exposure misclassification according to SES,53,56 several authors estimated pollutant concentrations at the resolution of city subdivisions. The exposure attributed to each subject was thus the prevalent concentration in his or her zone (as defined in each study: actual address16,46 or neighbourhood, at a more or less fine resolution26,32,45). It is difficult to appreciate to what extent these approaches really attenuate exposure misclassification relative to city‐wide measurements.

Except for two studies documenting the proximity of roads,16,46 the intra‐urban measurements used concern (local) urban background pollution. The quantity of pollutants added or subtracted to this local urban background may differ according to subjects' SES for several reasons: very local effects of emission sources on pollutant concentrations, penetration of exterior air pollutants into buildings (depending on building characteristics, such as air conditioning), sources of indoor pollution, passive smoking, etc.

Simple measurement of concentrations inside or outside the home does not take into account the subjects' time activity patterns57 including time spent at home, at work, in the neighbourhood, indoors or outdoors. Nonetheless, most people generally spend a substantial portion of their time at home (68% on average in the US58). The measurement of pollutant concentrations at home must therefore reflect at least part of the total exposure to pollutants, although more exhaustive and integrated exposure measurement would obviously be preferable. Unfortunately, the lack of available information about the possible differences in time activity patterns according to SES17 complicates the discussion of this aspect.

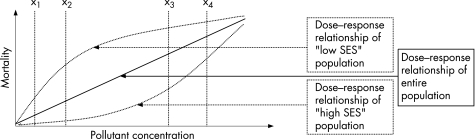

Each of the studies tested effect modification by SES only for a limited portion of the dose–response relationship between pollutant concentration and mortality. That is, in these studies, the relative risk is generally measured for an increase in the concentration of a pollutant (from concentration x1 to concentration x2). Some populations may conceivably be more susceptible than others to concentrations that are generally considered “low”. Other populations, less susceptible to these “low” concentrations, may become increasingly susceptible as the pollutant concentration increases. Figure 1 illustrates a fictitious example: the slope of a dose–response curve corresponding to a population with low SES might be stronger than that of a population with high SES for some concentration ranges (between x1 and x2), and lower for a range of higher concentrations (between x3 and x4). The slopes of these curves may be considered equivalent to relative risks. This shows the importance of taking into account the range of pollutant concentrations tested for which SES might be an effect modifier.

Figure 1 Fictitious example of dose–response relationships in populations with high and low SES.

Conclusion

The available studies do not allow confirmation or exclusion of an influence of SES on the relationship between air pollution and mortality. More studies with comparable designs are necessary to achieve that aim.

Future studies must, in so far as possible, use exposure measurements that minimise differential exposure misclassifications according to SES. They must also test the largest possible number of SES indicators (individual and contextual, at different geographic resolutions)31 simultaneously to identify the most discriminating in terms of relative risks of mortality associated with pollution.

Additional multicentre studies would guarantee harmonisation of the indicators and statistical methods used.59

What this paper adds

This first review of potential interactions between socioeconomic status and the effects of air pollution on mortality shows that the resolution at which socioeconomic characteristics are measured influences the results.

There is no effect modification for coarser geographic resolutions (city‐ or county‐wide) and there are mixed results for finer geographic resolutions, while such an interaction is relatively consistent when individual measures are used: poorer people tend to be more susceptible to the effects of air pollution.

Policy implications

Further research on this topic should consider the largest possible number of SES indicators (both individual and contextual) to identify the most discriminating in terms of relative risks of mortality associated with pollution.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jo Ann Cahn for her critical translation of this paper from the French.

Abbreviations

BMI - body mass index

CoH - coefficient of haze

NO2 - nitrogen dioxide

O3 - ozone

PM10 - particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of up to 10 μm

PM2.5 - particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of up to 2.5 μm

SES - socioeconomic status

SO2 - sulfur dioxide

TSP - total suspended particulates

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Chaturvedi N, Jarrett J, Shipley M J.et al Socioeconomic gradient in morbidity and mortality in people with diabetes: cohort study findings from the Whitehall Study and the WHO Multinational Study of Vascular Disease in Diabetes. BMJ 1998316(7125)100–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh G K, Siahpush M. Increasing inequalities in all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality among US adults aged 25–64 years by area socioeconomic status, 1969–1998. Int J Epidemiol 200231(3)600–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avendano M, Kunst A E, Huisman M.et al Socioeconomic status and ischaemic heart disease mortality in 10 western European populations during the 1990s. Heart 200692(4)461–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steenland K, Henley J, Thun M. All‐cause and cause‐specific death rates by educational status for two million people in two American Cancer Society cohorts, 1959–1996. Am J Epidemiol 2002156(1)11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh G K, Miller B A, Hankey B F.et al Changing area socioeconomic patterns in U.S. cancer mortality, 1950–1998: Part I‐‐All cancers among men, J Natl Cancer Inst 200294(12)904–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V.et al Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin 200454(2)78–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huisman M, Kunst A E, Andersen O.et al Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality among elderly people in 11 European populations. J Epidemiol Community Health 200458(6)468–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilman S E, Abrams D B, Buka S L. Socioeconomic status over the life course and stages of cigarette use: initiation, regular use, and cessation. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357(10)802–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irala‐Estevez J D, Groth M, Johansson L.et al A systematic review of socio‐economic differences in food habits in Europe: consumption of fruit and vegetables. Eur J Clin Nutr 200054(9)706–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez‐Azpiazu I, Sanchez‐Villegas A, Johansson L.et al Disparities in food habits in Europe: systematic review of educational and occupational differences in the intake of fat. J Hum Nutr Diet 200316(5)349–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunner E. Stress and the biology of inequality. BMJ 1997314(7092)1472–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adler N E, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Inequality in education, income, and occupation exacerbates the gaps between the health “haves” and “have‐nots”. Health Aff (Millwood) 200221(2)60–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans G W, Kantrowitz E. Socioeconomic status and health: the potential role of environmental risk exposure. Annu Rev Public Health 200223303–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodward A, Boffetta P. Environmental exposure, social class, and cancer risk. IARC Sci Publ 1997138361–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Tang M, Krewski D.et al Relationship between asthma prevalence and income among Canadians. JAMA 2001286(8)919–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finkelstein M M, Jerrett M, Sears M R. Environmental inequality and circulatory disease mortality gradients. J Epidemiol Community Health 200559(6)481–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Lung Association Urban air pollution and health inequities: a workshop report. Environ Health Perspect 2001109(Suppl 3)357–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Neill M S, Jerrett M, Kawachi I.et al Health, wealth, and air pollution: advancing theory and methods. Environ Health Perspect 2003111(16)1861–1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sexton K, Gong H, Jr, Bailar J C., IIIet al Air pollution health risks: do class and race matter? Toxicol Ind Health 19939(5)843–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowen W. An analytical review of environmental justice research: what do we really know? Environ Manage 200229(1)3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolinoy D C, Miranda M L. GIS modeling of air toxics releases from TRI‐reporting and non‐TRI‐reporting facilities: impacts for environmental justice. Environ Health Perspect 2004112(17)1717–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stroh E, Oudin A, Gustafsson S.et al Are associations between socio‐economic characteristics and exposure to air pollution a question of study area size? An example from Scania, Sweden. Int J Health Geogr 2005430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wheeler B W, Ben‐Shlomo Y. Environmental equity, air quality, socioeconomic status, and respiratory health: a linkage analysis of routine data from the Health Survey for England. J Epidemiol Community Health 200559(11)948–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brajer V, Hall J V. Changes in the distribution of air pollution exposure in the Los Angeles basin from 1990 to 1999. Contemporary Economic Policy 200523(1)50–58. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filleul L, Harrabi I. Do socioeconomic conditions reflect a high exposure to air pollution or more sensitive health conditions? J Epidemiol Community Health 200458(9)802. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jerrett M, Burnett R T, Brook J.et al Do socioeconomic characteristics modify the short term association between air pollution and mortality? Evidence from a zonal time series in Hamilton, Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health 200458(1)31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wojtyniak B, Rabczenko D, Stokwiszewski J. Does air pollution has respect for socio‐economic status of people [abstract]. Epidemiology 200112S64 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cifuentes L, Vega J, Lave L. Daily mortality by cause and socio‐economic status in Santiago, Chile 1988–1996 [abstract]. Epidemiology 199910S45 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jerrett M, Buzzelli M, Burnett R T.et al Particulate air pollution, social confounders, and mortality in small areas of an industrial city. Soc Sci Med 200560(12)2845–2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jerrett M, Burnett R T, Willis A.et al Spatial analysis of the air pollution‐mortality relationship in the context of ecologic confounders. J Toxicol Environ Health A 200366(16–19)1735–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braveman P A, Cubbin C, Egerter S.et al Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA 2005294(22)2879–2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martins M C, Fatigati F L, Vespoli T C.et al Influence of socioeconomic conditions on air pollution adverse health effects in elderly people: an analysis of six regions in Sao Paulo, Brazil. J Epidemiol Community Health 200458(1)41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romieu I, Ramirez‐Aguilar M, Moreno‐Macias H.et al Infant mortality and air pollution: modifying effect by social class. J Occup Environ Med 200446(12)1210–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villeneuve P J, Burnett R T, Shi Y.et al A time‐series study of air pollution, socioeconomic status, and mortality in Vancouver, Canada. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 200313(6)427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeka A, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Individual‐level modifiers of the effects of particulate matter on daily mortality. Am J Epidemiol 2006163(9)849–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samet J M, Dominici F, Curriero F C.et al Fine particulate air pollution and mortality in 20 U.S. cities, 1987–1994. N Engl J Med 2000343(24)1742–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filleul L, Rondeau V, Cantagrel A.et al Do subject characteristics modify the effects of particulate air pollution on daily mortality among the elderly? J Occup Environ Med 200446(11)1115–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz J. Assessing confounding, effect modification, and thresholds in the association between ambient particles and daily deaths. Environ Health Perspect 2000108(6)563–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Neill M S, Loomis D, Borja‐Aburto V H. Ozone, area social conditions, and mortality in Mexico City. Environ Res 200494(3)234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gouveia N, Fletcher T. Time series analysis of air pollution and mortality: effects by cause, age and socioeconomic status. J Epidemiol Community Health 200054(10)750–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Race, gender, and social status as modifiers of the effects of PM10 on mortality. J Occup Environ Med 200042(5)469–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bateson T F, Schwartz J. Who is sensitive to the effects of particulate air pollution on mortality? A case‐crossover analysis of effect modifiers. Epidemiology 200415(2)143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Filleul L, Baldi I, Dartigues J F.et al Risk factors among elderly for short term deaths related to high levels of air pollution. Occup Environ Med 200360(9)684–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krewski D, Burnett R T, Goldberg M.et alReanalysis of the Harvard Six Cities Study and the American Cancer Society Study of Particulate Air Pollution and Mortality. Cambridge, MA: Health Effects Institute. 2000

- 45.Filleul L, Rondeau V, Vandentorren S.et al Twenty five year mortality and air pollution: results from the French PAARC survey. Occup Environ Med 200562(7)453–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoek G, Brunekreef B, Goldbohm S.et al Association between mortality and indicators of traffic‐related air pollution in the Netherlands: a cohort study. Lancet 2002360(9341)1203–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Finkelstein M M, Jerrett M, DeLuca P.et al Relation between income, air pollution and mortality: a cohort study. CMAJ 2003169(5)397–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dockery D W, Pope C A, III, Xu X.et al An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. N Engl J Med 1993329(24)1753–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pope C A, III, Thun M J, Namboodiri M M.et al Particulate air pollution as a predictor of mortality in a prospective study of U.S. adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995151(3 Pt 1)669–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pope C A, III, Burnett R T, Thun M J.et al Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long‐term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA 2002287(9)1132–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Filliger P, Puybonnieux‐Texier V, Schneider J.Health costs due to road traffic‐related air pollution. An impact assessment project of Austria, France and Switzerland. Prepared for the WHO Ministerial Conference for Environment and Health. Geneva: WHO, 1999

- 52.Katsouyanni K, Touloumi G, Spix C.et al Short‐term effects of ambient sulphur dioxide and particulate matter on mortality in 12 European cities: results from time series data from the APHEA project. BMJ 1997314(7095)1658–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Finkelstein M M. Pollution‐related mortality and educational level. JAMA 2002288(7)830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jerrett M, Burnett R T, Ma R.et al Spatial analysis of air pollution and mortality in Los Angeles. Epidemiology 200516(6)727–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rotko T, Koistinen K, Hanninen O.et al Sociodemographic descriptors of personal exposure to fine particles (PM2.5) in EXPOLIS Helsinki. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 200010(4)385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lipfert F W. Air pollution and poverty: does the sword cut both ways? J Epidemiol Community Health 200458(1)2–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Briggs D. The role of GIS: coping with space (and time) in air pollution exposure assessment. J Toxicol Environ Health A 200568(13–14)1243–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsang A M, Klepeis N E. Results tables from a detailed analysis of the National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS) response. Draft Report prepared for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency by Lockheed Martin, Contract No. 68 W6‐001, Delivery Order No. 13. Washington, DC: EPA, 1996

- 59.Samet J M, White R H. Urban air pollution, health, and equity. J Epidemiol Community Health 200458(1)3–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]