Abstract

Background

: Research to investigate levels of organisational capacity in public health systems to reduce the burden of chronic disease is challenged by the need for an integrative conceptual model and valid quantitative organisational level measures.

Objective

To develop measures of organisational capacity for chronic disease prevention/healthy lifestyle promotion (CDP/HLP), its determinants, and its outcomes, based on a new integrative conceptual model.

Methods

Items measuring each component of the model were developed or adapted from existing instruments, tested for content validity, and pilot tested. Cross sectional data were collected in a national telephone survey of all 216 national, provincial, and regional organisations that implement CDP/HLP programmes in Canada. Psychometric properties of the measures were tested using principal components analysis (PCA) and by examining inter‐rater reliability.

Results

PCA based scales showed generally excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.70 to 0.88). Reliability coefficients for selected measures were variable (weighted κ(κw) = 0.11 to 0.77). Indicators of organisational determinants were generally positively correlated with organisational capacity (rs = 0.14–0.45, p<0.05).

Conclusions

This study developed psychometrically sound measures of organisational capacity for CDP/HLP, its determinants, and its outcomes based on an integrative conceptual model. Such measures are needed to support evidence based decision making and investment in preventive health care systems.

Keywords: organisational capacity, public health, chronic disease, psychometrics, preventive health services

Chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancer, diabetes, and respiratory illness, remain an enormous and growing burden on health care systems in Canada1,2 and elsewhere.3 Although many chronic diseases are preventable, there are few examples of successful chronic disease prevention and healthy lifestyle promotion (CDP/HLP) programmes that reduce population level morbidity and mortality.4 Based on increased understanding that health systems are important socioenvironmental determinants of health,5 researchers are now investigating whether health systems, and more specifically organisations that develop and deliver CDP/HLP programmes within health systems, have adequate capacity to contribute effectively to reducing the chronic disease burden. However, these efforts have encountered at least three challenges.

First, despite growing interest in this area, there is no widely accepted definition of organisational capacity in the health context. Organisational capacity has been defined variably in the research literature, borrowing from definitions used in research on practitioner capacity6 or community/organisational capacity building for health promotion, or both.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 Within the public health context, Hawe et al15 conceptualised organisational capacity for health promotion (“capacity of an organisation to tackle a particular health issue”) as having at least three domains: organisational commitment, skills, and structures. Labonte and Laverack12 described government/non‐governmental organisational capacity as the structures, skills, and resources required to deliver programme responses to specific health problems. Within the CVD prevention/heart health promotion domain, organisational capacity for conducting effective health promotion programmes has been conceptualised as a set of skills and resources.16 This definition was expanded to include knowledge17 and commitments.18 Others19 have adopted the Singapore Declaration definition of organisational capacity5 as the capability of an organisation to promote health, formed by the will to act, infrastructure, and leadership. Finally, Naylor et al20 included infrastructure, collaboration, evidence base, policy, and technical expertise as components of a capable organisation. Overall, skills and resources to conduct CDP/HLP programmes emerge in these reports as the two most common dimensions of organisational capacity in the public health context.

An issue related to lack of conceptual clarity is that, while substantial efforts have been made to identify dimensions of organisational capacity, few investigators have formulated clear conceptual boundaries between organisational capacity, its determinants, and its outcomes. In their surveys of Ontario public health units (PHUs) in 1994 and 1996, Elliott et al21 and Taylor et al16 distinguished between predisposition (that is, level of importance ascribed to public health practices supportive of heart health initiatives), capacity (effectiveness in performing these practices), and implementation of heart health activities. This conceptual framework posited that capacity and predisposition are interrelated, and these in turn relate to implementation. In empirical testing of the framework, there were moderate correlations between predisposition and capacity, moderate to strong correlations between capacity and implementation, but no correlation between predisposition and implementation. Building on this framework, Riley et al22 undertook path analysis using the same database to examine the relations between 1997 levels of implementation and four sets of determinants: internal organisational factors; external system factors; predisposition; and capacity. The results supported a strong direct relation between capacity and implementation, and provided evidence that external system factors (that is, partnerships, support from resource centres) and internal organisational factors (coordination of programmes within the health unit) have an indirect impact on implementation by influencing capacity. Predisposition was not retained in the model. Priority given to heart health within PHUs had a direct relation with implementation. In 2001, McLean et al18 proposed that the relation between organisational capacity and heart health promotion action is mediated by external factors such as funding and policy frameworks of provincial and national governments, and public understanding of health promotion. However external factors were treated as one of four indices of capacity in their analyses.

A second challenge is the lack of validated quantitative measures of organisational capacity, its determinants, and its outcomes. Qualitative work has predominated in this area, and although informative in terms of rich descriptive and locally meaningful information, qualitative research does not lend itself to generalisation across organisations and jurisdictions. Quantitative work is needed to support qualitative work, and to provide decision makers with standardised tools for measuring, managing, and improving CDP/HLP capacity. Measures of organisational capacity developed to date often include large numbers of diverse items in an effort to capture all possible dimensions of capacity. Although content validity is reported to be high for most measures,23 data on construct validity and reliability are limited, and few investigators have formally tested the psychometric properties of their measures.24,25

A third challenge is that there are no nationally representative data on levels of organisational capacity in organisations with mandates for CDP/HLP. Such data are needed to guide evidence based investment in building preventive health systems, and in particular to identify gaps and monitor changes in capacity over time. To date, surveys have been restricted to include only formally mandated public health organisations in specific geographical regions, with the exception of one survey that included both health community and non‐health‐community agencies involved in heart health promotion 17, and comparison across surveys is impeded because of the differing operational definitions of organisational capacity.

To address these challenges, we undertook a national survey of all organisations in Canada with mandates for CDP/HLP. The specific aims of this paper are twofold. First, we introduce a conceptual framework for research on preventive health services. Second, we describe the development of quantitative measures of organisational capacity for CDP/HLP, as well as possible determinants and outcomes of organisational capacity.

Conceptual framework

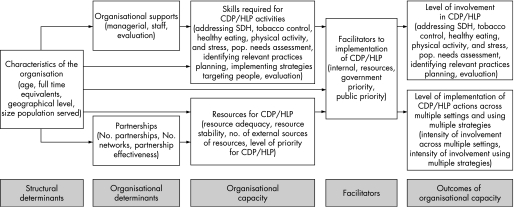

Our conceptual framework (fig 1) addresses the challenges outlined above by, first, adopting a parsimonious conceptualisation of capacity that encompasses skills and resources; second, separating factors purportedly related to creating capacity into organisational or structural determinants of capacity; third, postulating links between capacity and outcomes of capacity (that is, although there are many potential outcomes of capacity, level of involvement in CDP/HLP activities is the outcome of most interest in our framework); fourth, positioning facilitators as mediators between capacity and outcomes; and fifth, more generally, adopting an approach suitable for empirical testing of the overall model. Rather than creating global scores that summarise factors within the conceptual framework, we retain each variable as a unique entity. This will enhance empirical testing of the framework by allowing investigation of each factor separately, as well as the association between factors.

Figure 1 Conceptual framework depicting potential determinants and outcomes of organisational capacity for chronic disease prevention and healthy lifestyle promotion (CDP/HLP). Organisational capacity for CDP/HLP is conceptualised as resources and skills required to implement CDP/HLP activities. Structural determinants of capacity include characteristics of the organisation. Organisational determinants include supports for developing/maintaining organisational capacity, as well as partnerships with other organisations. These are explicitly separated from capacity because they are seen as possible determinants of specific skills required for CDP/HLP capacity. Facilitators include factors internal and external to the organisation that mediate the impact of capacity on outcomes. Finally outcomes related to capacity include level of involvement in specific types of CDP/HLP activities, and extent of implementation (intensity of involvement) of CDP/HLP activities across multiple settings and using multiple implementation strategies. SDH, social determinants of health.

Methods

Based on a comprehensive review of published reports, items were adapted from earlier questionnaires designed to measure organisational practices/activities for (heart) health promotion8,11,15,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 or developed de novo. The content of an initial version of the questionnaire was validated by four researchers (recognised nationally for their work related to chronic disease health policy, health promotion, public health, and dissemination), and then a revised version was pretested in telephone interviews with nine organisations that delivered prevention activities unrelated to chronic disease. Pretest respondents included executive directors and programme or evaluation staff from public health departments, resource centres, or non‐profit organisations across Canada with mandates for infectious disease, injury prevention, or the health and development of children. The final version comprised 258 items covering the following: organisational characteristics (that is, structural determinants of capacity) (14 items); organisational supports of capacity (21 items); skills (41 items); resources (20 items); involvement in CDP/HLP (30 items); implementation of CDP/HLP activities (60 items); partnerships (seven items); facilitators/barriers (24 items); respondent characteristics (seven items); and skip or descriptive items (34 items). Most response sets were five point Likert scales, with degree/extent or agreement response formats ranging from “1” (very low/strongly disagree) to “5” (very high/strongly agree).

Two francophone translators translated the questionnaire from English into French. Equivalence between the source and target language versions was verified according to recommendations for cross cultural adaptations of health measures.37,38

To identify organisations for inclusion in the survey, we undertook a complete census of all regional, provincial, and national organisations across Canada with mandates for the primary prevention of chronic disease (that is, diabetes, cancer, CVD, or chronic respiratory illness) or for the promotion of healthy eating, non‐smoking, or physical activity. Government departments, regional health authorities/districts, public health units, non‐governmental organisations (NGOs) and their provincial/regional divisions, paragovernmental health agencies, resource centres, professional organisations, and coalitions, alliances and partnerships were identified in an exhaustive internet search and through consultations with key informants across Canada. All 353 organisations identified were invited to participate. Initial screening interviews were conducted with senior managers to confirm that the organisation met the inclusion criteria, to solicit participation, and to obtain contact information for potential respondents. Inclusion criteria were: that the organisation was mandated to undertake primary prevention of chronic disease; that it was involved in developing/adopting programmes, practice tools, skill or capacity building initiatives, campaigns, activities, and so on; and that it had transferred these innovations to other organisations in the past three years or had implemented the innovations in a specific target population.

Organisations that adopted or developed CDP/HLP innovations with the intention of delivering these innovations in specific populations were labelled “user” organisations. Those that developed and transferred CDP/HLP innovations to other organisations were labelled “resource” organisations. Of 280 organisations screened and eligible, 49 were resource organisations, 180 were user organisations, and 32 were both user and resource organisations. Sixty‐eight organisations were not eligible to participate (that is, they were mandated to provide secondary prevention, they targeted aboriginal populations only, or they were primarily involved in advocacy activities, fund allocation, fund raising, facilitation of joint efforts among organisations, research only, or knowledge transfer (not developing/adopting CDP/HLP innovations for implementation). Nineteen eligible organisations declined to participate. The response proportion was 92%.

Data were collected in structured telephone interviews (mean length 43±17 minutes) with individuals identified by the senior manager as most knowledgeable about implementation/delivery of CDP/HLP programmes, practices, campaigns, or activities. One interview was conducted per organisation, except in organisations where senior managers identified more than one autonomous division/branch within the organisation that conducted CDP/HLP activities. In these organisations, interviews were conducted with one knowledgeable person in each autonomous division. Interviews were conducted in English or French between October 2004 and April 2005 by nine trained interviewers. Respondents included senior/middle managers, service providers, and professional staff. Random monitoring of interviews was conducted for quality control. Inconsistencies and incomplete data were resolved in telephone calls or e‐mails.

To assess interrater reliability, a second interview was completed in a subsample of 26 organisations, with a second individual knowledgeable about implementation/delivery of CDP/HLP programmes, practices, campaigns, or activities. Respondents within the same organisation were interviewed separately by the same interviewer.

Data were entered into a database management system developed by DataSpect Software, Montreal, Quebec. All data entries were verified for accuracy by one investigator (NH).

Data analysis

This analysis pertains to 216 “user organisations,” which represent a complete census of Canadian organisations engaged in adopting or developing and implementing CDP/HLP innovations in select target populations.

We undertook separate psychometric analyses for subsets of items selected to measure each construct in the conceptual framework, in order to assess unidimensionality and internal consistency. To determine whether principal components analysis (PCA) was an appropriate analytic option, we undertook the following checks: assessment of normality in individual items; verification of the absence of outliers; and examination of patterns of missing data.39 No imputation of missing data was required because few data were missing. All Bartlett's tests of sphericity achieved significance, and all Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin coefficients were ⩾0.6, showing that the data were appropriate for PCA analysis. The principal components method with varimax rotation was used to extract factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. Decisions about the number of factors to retain were based on Cattell's scree test40 and the number of factors needed to account for ⩾50% of the variance in the measured variables.41

Items with factor loadings ⩾0.44 were retained to construct unit weighted scales, with stipulation that an item could not be retained in more than one factor, that each factor contained a minimum of three items, and that items loading on a given factor shared the same conceptual meaning.42 Items that did not fit these criteria were treated as single item measures (n = 8) or dropped (n = 12) if they did not represent a key concept in the conceptual framework.

Cronbach's α43 and mean inter‐item correlations44 were computed to measure internal consistency. The range and distribution of individual inter‐item correlations were examined to confirm unidimensionality.44 Interpretive labels were assigned to each scale.

Factor based scores for each scale were computed only for organisations that had data for at least 50% of scale items. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were computed to describe associations between hypothesised determinants and each of the skills and resources scales of the capacity construct.

PCA based scale construction was not appropriate for two components of the conceptual framework (“resources available for CDP activities” and “intensity of involvement in CDP activities”), either because items selected to measure the component did not share the same response categories or they did not represent one single underlying construct. In both cases, scores were developed using arithmetic combinations of items, aiming to approximate normal distributions. The scoring strategy created two “all risk factor” scores (intensity of involvement (i) multiple settings score or (ii) multiple strategies score). Variations in sample size associated with differences in mandated risk factor programming required creation of an “intensity of involvement score” for each risk factor separately.

Inter‐rater reliability coefficients (that is, per cent agreement and weighted κ45) using quadratic (standard) weights, were computed for selected variables.

Data analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and SPSS software release 11 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois). The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Faculty of Medicine of McGill University.

Results

Of the 216 organisations surveyed, 103 regional health authorities/districts and public health units/agencies were within the formal public health system. The remainder included NGOs (n = 54), coalitions, partnerships or alliances (n = 41), and others (government departments, paragovernmental health agencies, professional associations, and so on) (n = 18). Table 1 presents selected characteristics of participating organisations.

Table 1 Selected characteristics of the study population (n = 216).

| Organisation | |

|---|---|

| Organisation type (n (%)) | |

| Formal public health* | 103 (48) |

| NGO | 54 (25) |

| Alliance, coalition, partnership | 41 (19) |

| Other† | 18 (8) |

| Size, median (range) | |

| Age (years) | 27 (1.5 to 150) |

| Number full time equivalents | 53 (0 to 25 000) |

| Number volunteers | 35 (0 to 50 000) |

| Geographical area served (n (%)) | |

| Regional | 154 (71) |

*Regional health authorities and public health departments/agencies.

†Government, paragovernmental health agencies, professional associations, resource centres, other.

Overall, PCA confirmed our conceptualisation of the scales used to measure the components of our conceptual framework. Through PCA, we consolidated 124 individual items into 20 psychometrically sound scales, facilitating analysis and interpretation of these data. The components of our conceptual framework were measured in 32 multi‐item scales/scores and 15 single item indicators (table 2). Factor loadings for items in the 20 scales were generally ⩾0.71. Cronbach's α values were consistently above 0.64 and mean inter‐item Spearman rank correlation coefficients ranged between 0.30 and 0.57, demonstrating good to very good internal consistency. Unidimensionality of scales was confirmed. Most inter‐item correlations ranged from 0.20 to 0.70 and within each scale were clustered around their respective means.

Table 2 Measures of organisational capacity, and of potential determinants and outcomes of organisational capacity, including psychometric properties of scales developed.

| Measure* | No of items | Cronbach's α | Mean (SD) inter‐item correlation | Range of inter‐item correlations | Highest loading item |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organisational supports† | |||||

| Managerial | 9 | 0.88 | 0.49 (0.09) | 0.37 to 0.73 | Managers are accessible regarding CDP/HLP activities |

| Staff | 6 | 0.72 | 0.32 (0.12) | 0.21 to 0.67 | There are professional development opportunities to learn about CDP/HLP |

| Evaluation | 3 | 0.77 | 0.52 (0.17) | 0.40 to 0.71 | Monitoring and evaluation information about our CDP/HLP activities is available |

| Partnerships† | |||||

| Effectiveness | 5 | 0.75 | 0.37 (0.11) | 0.25 to 0.60 | Partnerships with other organisations are bringing new ideas about CDP/HLP to your organisation |

| Skills to address‡ | Over the last three years, how would you rate your organisation's skill level: | ||||

| Social determinants of health | 6 | 0.86 | 0.50 (0.12) | 0.27 to 0.72 | –in CDP/HLP activities that address social exclusion? |

| Population needs assessment | 3 | 0.80 | 0.56 (0.16) | 0.47 to 0.74 | –for assessing the prevalence of risk factors? |

| Identify relevant practices | 6 | 0.85 | 0.49 (0.10) | 0.35 to 0.70 | –for reviewing CDP/HLP activities developed by other organisations to see if they can be used by your organisation? |

| Planning | 5 | 0.88 | 0.57 (0.08) | 0.49 to 0.70 | –for developing action plans for CDP/HLP? |

| Implementation strategies | 6 | 0.80 | 0.39 (0.07) | 0.17 to 0.46 | –for service provider skill building? |

| Evaluation | 6 | 0.88 | 0.55 (0.09) | 0.41 to 0.73 | –for measuring achievement of CDP/HLP objectives? |

| Resources§ | |||||

| Adequacy | 3 | 0.77 | 0.52 (0.14) | 0.41 to 0.68 | How adequate are the funding levels for CDP/HLP activities in your organisation? |

| Facilitators# | |||||

| Internal | 6 | 0.72 | 0.32 (0.13) | 0.16 to 0.57 | Organisational structure for CDP/HLP |

| Resources | 4 | 0.83 | 0.55 (0.17) | 0.38 to 0.79 | Usefulness of the provincial resource organisations for CDP/HLP |

| Government priority | 5 | 0.76 | 0.36 (0.17) | 0.18 to 0.74 | Level of provincial priority for CDP/HLP |

| Public priority | 5 | 0.70 | 0.31 (0.13) | 0.19 to 0.58 | Level of public understanding of CDP/HLP |

| Level of involvement¶ | Over the last three years, how would you rate your organisation's involvement in: | ||||

| SDH | 6 | 0.84 | 0.48 (0.10) | 0.30 to 0.67 | –CDP/HLP activities that address socioeconomic status? |

| Population needs assessment | 3 | 0.81 | 0.57 (0.15) | 0.47 to 0.75 | –assessing the prevalence of risk factors? |

| Identify relevant practices | 6 | 0.84 | 0.46 (0.12) | 0.29 to 0.70 | –finding relevant best practices in CDP/HLP to see if they can be used by your organisation? |

| Planning | 5 | 0.86 | 0.54 (0.10) | 0.43 to 0.71 | –developing action plans for CDP/HLP? |

| Evaluation | 6 | 0.86 | 0.50 (0.12). | 0.32 to 0.77 | –measuring achievement of CDP/HLP objectives? |

| Intensity of involvement – multiple settings¶,**,†† | How would you rate your organisation's level of involvement in: | ||||

| Tobacco control | 4 | 0.73 | 0.41 (0.04) | 0.37 to 0.46 | –tobacco control activities in the following settings? |

| Healthy eating | 4 | 0.64 | 0.30 (0.11) | 0.12 to 0.40 | –healthy eating activities in the following settings? |

| Physical activity | 4 | 0.71 | 0.38 (0.15) | 0.10 to 0.54 | –physical activity activities in the following settings? |

| Mixed risk factor‡‡ | 4 | 0.70 | 0.35 (0.12) | 0.12 to 0.47 | –multiple risk factor activities in the following settings? |

| Multiple settings score | 16 | 0.89 | 0.35 (0.15) | −0.01 to 0.74 | Score based on quintiles of cumulative frequency distribution of the sum of the above four variables |

| Intensity of involvement – multiple strategies¶,§§,## | How would you rate your organisation's level of involvement in: | ||||

| Tobacco control | 11 | 0.87 | 0.38 (0.14) | 0.03 to 0.69 | –tobacco control activities using the following strategies? |

| Healthy eating | 11 | 0.86 | 0.36 (0.14) | 0.07 to 0.71 | –healthy eating activities using the following strategies? |

| Physical activity | 11 | 0.89 | 0.43 (0.11) | 0.20 to 0.72 | –physical activity activities using the following strategies? |

| Mixed risk factor‡‡ | 11 | 0.90 | 0.42 (0.13) | 0.12 to 0.74 | –multiple risk factor activities using the following strategies? |

| Multiple strategies score | 44 | 0.96 | 0.33 (0.14) | −0.06 to 0.79 | Score based on quintiles of cumulative frequency distribution of the sum of the above four variables |

*Measures providing no information on psychometric properties (single items or not PCA based) are not shown; numbers used in analyses varied: organisational supports (207–215); partnerships (215); skills (213–216); resources (215); facilitators (216); level of involvement (213–216); intensity of involvement across multiple settings (93–190); intensity of involvement using multiple strategies (92–189).

†Response category 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree; ‡1 = poor to 5 = very good; §1 = much less than adequate to 5 = more than adequate; #−3 = strong barrier to +3 = strong facilitator; ¶1 = very low to 5 = very high.

**Settings included schools, workplaces, health care settings, community at large.

††For intensity of involvement across multiple settings for individual risk factors, items were summed, creating a range from 4 to 20. This total was recoded from 1 to 5 with 1 = least intensely involved (sum 4–7); 2 = less intensely involved (sum 8–10); 3 = moderately involved (sum 11–12); 4 = highly involved (sum 14–16); 5 = very highly involved (sum 17–20). For intensity of involvement (multiple settings score): 16 responses were summed, creating a range from 16 to 80. These totals were recoded from 1 to 5 based on quintiles of the cumulative frequency.

‡‡Mixed risk factor accounts for activities that combine two or more behavioural risk factors (tobacco, nutrition, physical activity); no double counting.

§§Strategies included: group development; public awareness and education; skill building at individual level; healthy public policy development; advocacy; partnership building; community mobilisation; facilitation of self help groups; service provider skill building; creating healthy environments; volunteer recruitment and development.

##For intensity of involvement using multiple strategies for individual risk factors, items were summed creating a range from 11 to 55. Total was recoded from 1 to 5 with 1 = least intensely involved (sum 11–20); 2 = less intensely involved (sum 21–28); 3 = moderately involved (sum 29–36); 4 = highly involved (sum 37–44); 5 = very highly involved (sum 45–55). For intensity of involvement (multiple strategies score): 44 responses were summed, creating a range from 44 to 220. These totals were recoded from 1 to 5, based on quintiles of the cumulative frequency.

Interrater reliability coefficients were low to moderate for the 19 variables tested, with per cent agreement ranging from 12.5% for “intensity of involvement in healthy eating using multiple strategies” to 66.7% for “intensity of involvement in tobacco control across multiple settings” (table 3). Weighted κ coefficients which correct for chance and take partial agreement into consideration were generally less conservative, but nonetheless ranged between 0.11 and 0.78.

Table 3 Interrater reliability of measures of potential outcomes of organisational capacity (n = 17 pairs of raters)*.

| Per cent agreement | Weighted κ | |

|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | ||

| Level of involvement | ||

| SDH | 41.2 | 0.32 (0.00 to 0.65) |

| Tobacco control | 41.2 | 0.65 (0.38 to 0.93) |

| Healthy eating | 47.1 | 0.55 (0.20 to 0.89) |

| Physical activity | 47.1 | 0.59 (0.25 to 0.92) |

| Stress | 35.3 | 0.42 (0.01 to 0.83) |

| Population needs assessment | 31.3 | 0.54 (0.26 to 0.82) |

| Identifying relevant practices | 50.0 | 0.25 (−0.20 to 0.70) |

| Planning | 47.1 | 0.27 (−0.14 to 0.69) |

| Evaluation | 35.3 | 0.11 (−0.27 to 0.48) |

| Intensity of involvement across multiple settings | ||

| Tobacco control | 66.7 | 0.77 (0.50 to 1.04) |

| Physical activity | 55.6 | 0.40 (−0.21 to 1.01) |

| Healthy eating | 12.5 | 0.45 (0.02 to 0.89) |

| Mixed risk factor | 56.3 | 0.77 (0.65 to 0.90) |

| Multiple settings score | 47.1 | 0.54 (0.17 to 0.92) |

| Intensity of involvement using multiple strategies | ||

| Tobacco control | 50.0 | 0.78 (0.59 to 0.98) |

| Physical activity | 33.3 | 0.51 (0.13 to 0.89) |

| Healthy eating | 25.0 | 0.40 (0.09 to 0.71) |

| Mixed risk factor | 37.5 | 0.40 (0.06 to 0.75) |

| Multiple strategies score | 29.4 | 0.65 (0.38 to 0.92) |

*Nine of 26 pairs of raters rated different organisational units or levels. Analyses are presented for the 17 pairs that rated the same organisational unit/level.

CI, confidence interval; SDH, social determinants of health.

Determinants of organisational capacity were weakly or moderately correlated with organisational capacity indicators (table 4). Few statistically significant correlations were observed between organisational capacity indicators and hypothesised structural determinants, with the exception that size of organisation was positively correlated with external sources of funding (rs = 0.26), and negatively correlated with priority for CDP/HLP (rs = −0.41). Indicators of organisational supports were generally significantly and positively correlated with organisational capacity. Correlations between skills (identification of relevant practices, planning, implementation strategies, and evaluation) and resources (adequacy and priority) ranged between 0.21 and 0.45. Partnerships were also robustly correlated with several indicators of skills and with external sources of funding, but correlations were generally weak, ranging between 0.14 and 0.23.

Table 4 Spearman rank correlation coefficients between indicators of organisational capacity and potential determinants of organisational capacity (n = 216).

| Indicators of organisational capacity | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skills | Resources | ||||||||||||||

| Risk factors | Population needs assessment | Identify relevant practices | Planning | Implementation strategies | Evaluation | Adequacy | Stability | External sources | Priority for CDP/HLP | ||||||

| SDH | Tobacco | Healthy eating | Physical activity | Stress | |||||||||||

| Structural determinants | |||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.05 | 0.18** | −0.04 | −0.09 | 0.0 | 0.16* | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.21** | −0.15* | |

| Size of organisation | 0.08 | 0.14* | 0.08 | −0.15* | 0.12 | 0.17* | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.10 | −0.17* | 0.0 | 0.26** | −0.41** | |

| Organisational supports | |||||||||||||||

| Managerial | 0.19** | 0.14* | 0.18** | 0.32** | 0.12 | 0.23** | 0.36** | 0.37** | 0.33** | 0.36** | 0.29** | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.41** | |

| Staff | 0.01 | 0.14* | 0.14* | 0.16* | 0.04 | 0.15* | 0.21** | 0.31** | 0.18** | 0.25** | 0.43** | 0.16* | 0.05 | 0.36** | |

| Evaluation | 0.09 | 0.20** | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.16* | 0.26** | 0.45** | 0.29** | 0.43** | 0.29** | 0.06 | 0.18** | 0.24** | |

| Partnerships | |||||||||||||||

| Number | 0.05 | 0.20** | 0.17* | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.23** | 0.16* | 0.17* | 0.14* | −0.11 | −0.04 | 0.21** | 0.0 | |

| Effectiveness | 0.16* | 0.12 | 0.18** | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.18** | 0.23** | 0.20** | 0.21** | 0.11 | 0.25** | −0.05 | 0.19** | 0.19** | |

*p>0.05; **p>0.01.

CDP/HLP, chronic disease prevention/healthy lifestyle promotion; SDH, social determinants of health.

Discussion

There are major gaps in knowledge on organisational capacity for CDP/HLP,23 related in part to the lack of a widely accepted, well grounded conceptual model, as well as to the lack of reliable measurement instruments. This paper provides conceptual and empirical clarification of the dimensions, determinants, and outcomes of organisational capacity to undertake CDP/HLP in public health organisations. We propose a series of psychometrically sound measurement instruments using data from the first national survey on levels of organisational capacity and implementation of CDP/HLP activities across Canada, with organisations as the unit of analysis.

Our PCA based scales showed good psychometric properties including very good to excellent internal consistency, as well as evidence of unidimensionality. Interrater reliabilities were generally low for at least two reasons. First, most indicators comprised multiple items (that is, 15–20 items per scale/score) so that the probability of disagreement between raters by chance alone is higher than would be for single item indicators. Second, because organisations are inherently complex, data provided by a single individual may not reliably reflect the characteristics of, and processes within, organisations. Steckler et al46 suggested an alternative data collection strategy, namely to solicit a collective response through group interviews or questionnaires. Although possibly more valid, this method may be costly, more difficult to control, and in addition might require a level of organisational commitment that affects response proportions negatively. Another strategy for collecting organisational level data is to interview several respondents within the same organisation and then average their scores. If raters disagree, this strategy may not be more useful than interviewing single respondents as the resulting averages may not represent coherent perspectives.

What is already known

There are major gaps in our knowledge of the capacity of public health organisations to undertake community based chronic disease prevention/healthy lifestyle promotion programming

Researchers encounter three challenges: lack of a widely accepted conceptual model designed to enhance empirical testing of associations between organisational capacity, its hypothesised determinants, and outcomes; lack of validated, quantitative measurement instruments of organisational capacity, its determinants, and outcomes; and no nationally representative data on levels of organisational capacity.

What this paper adds

We propose a series of psychometrically sound measurement instruments using data from the first national survey on levels of organisational capacity and implementation of CDP/HLP activities across Canada with organisations as the unit of analysis.

Policy implications

Tools to facilitate systematic investigation of organisational capacity within public health systems are needed to support evidence based decision making and investment in chronic disease prevention.

Although κw values were generally low, higher interrater agreement was observed for several measures, notably those related to tobacco control. This could reflect the fact that tobacco control programmes have existed in Canada for over 30 years, whereas public health interventions related to other risk factors such as stress or reducing social disparities are relatively new. The longstanding presence of tobacco control activities may have contributed to more consistent perceptions between respondents within the same organisation about the nature of such activities.

Our results uphold our conceptual model, in terms both of its delineation of variables and of the relation between these variables. Factors related to organisational supports were moderately related to capacity. These factors represent ways in which organisations provide information, staff, and professional development opportunities for CDP/HLP, use monitoring and evaluation in decisions about CDP/HLP programming, and provide leadership and commitment for CDP/HLP. Riley et al22 observed that internal organisational factors (similar to our support factors) were indirectly related to implementation of heart health promotion activities through their effect on capacity. Partnership related variables might also be important in understanding organisational capacity. Whereas partnerships were once viewed as an option for public health organisations, they are now increasingly seen as necessary to respond to the chronic disease burden. Partnerships can create mechanisms for public health organisations with limited financial resources to increase knowledge, resources, and skills.47,48

Limitations of this study include the fact that data were collected from only one respondent within each organisation, albeit a respondent carefully selected as most knowledgeable about CDP/HLP. As all measures were collected from the same respondent, correlations between measures may result from artefactual covariance rather than substantive differences.49 However, most measures were not highly correlated, suggesting that this may not be a problem. Ideally, organisational level constructs should be assessed using objective measures, but self report is the most common method of data collection in organisational research. While we investigated content validity and both internal and interrater reliability of our measures, we could not examine criterion related validity because there are no gold standard measures of the indicators of interest. While cross sectional data can generate hypotheses about the relations between variables in our conceptual model, longitudinal data are needed to investigate whether these associations might be causal.

In summary, we propose several tools to facilitate systematic investigation of organisational capacity within public health systems. Based on an integrative conceptual model for research on organisational capacity, we developed conceptually and psychometrically sound measures of organisational capacity for CDP/HLP to support evidence based decision making and investment in preventive health systems.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge provincial contacts for their participation in creating the comprehensive list of organisations/senior managers and for their input regarding questionnaire development. We also express our appreciation to the pilot and study organisations and to Garbis Meshefedjian and Dexter Harvey for their contributions.

Abbreviations

CDP/HLP - chronic disease prevention/healthy lifestyle promotion

CVD - cardiovascular disease

NGO - non‐governmental organisation

PCA - principal components analysis

PHU - public health unit

Footnotes

Funding: This research is supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Nancy Hanusaik is the recipient of a CIHR Fellowship and was initially funded by training awards from the Fonds de la recherche en santé (FRSQ) and the Transdisciplinary Training Program in Public and Population Health (Quebec Population Health Research Network and CIHR).

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Statistics Canada Statistical report on the health of Canadians. Catalogue No 82‐570‐XIE. Ottawa: Ministry of Public Works and Government Services, 1999

- 2.Health Canada Economic burden of illness in Canada, 1998. Catalogue No H21‐136/1998E. Ottawa: Ministry of Public Works and Government Services, 2002

- 3.World Health Organisation Preventing chronic diseases: a vital investment. Geneva: WHO, 2005

- 4.Winkleby M A, Feldman H A, Murray D M. Joint analysis of three US community intervention trials for reduction of cardiovascular disease risk. J Clin Epidemiol 199750645–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearson T A, Bales V S, Blair L.et al The Singapore Declaration: forging the will for heart health in the next millennium. CVD Prevention 19981182–199. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raphael D, Steinmetz B. Assessing the knowledge and skills of community‐based health promoters. Health Promot Int 199510305–315. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson C, Fortmann S P, Flora J A.et al The capacity‐building approach to intervention maintenance implemented by the Stanford Five‐City Project. Health Educ Res 19949385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman R, Speers M, McLeroy K.et al Identifying and defining the dimensions of community capacity to provide a basis for measurement. Health Educ Behav 199825258–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawe P, Noort M, King L.et al Multiplying health gains: the critical role of capacity building within health promotion programs. Health Policy 19973929–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodman R M, Steckler A, Alciati M H. A process evaluation of the National Cancer Institute's data‐based intervention research program: a study of organizational capacity building. Health Educ Res 199712181–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crisp B, Swerissen H, Duckett S. Four approaches to capacity building in health: consequences for measurement and accountability. Health Promot Int 20001599–107. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labonte R, Laverack G. Capacity building for health promotion. Part 1. For whom? And for what purpose? Crit Public Health 200111111–127. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Labonte R, Laverack G. Capacity building for health promotion. Part 2. Whose use? And with what measurement? Crit Public Health 200111129–138. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Germann K, Wilson D. Organizational capacity for community development in regional health authorities: a conceptual model. Health Promot Int 200419289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawe P, King L, Noort M.et alIndicators to help with capacity‐building in health promotion. North Sydney: NSW Health Department, 1999

- 16.Taylor S M, Elliott S, Riley B. Heart health promotion: predisposition, capacity and implementation in Ontario public health units, 1994–96. Can J Public Health 199889410–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heath S, Farquharson J, MacLean D.et al Capacity‐building for health promotion and chronic disease prevention – Nova Scotia's experience. Promot Educ 2001(suppl 1)17–22. [PubMed]

- 18.McLean S, Ebbesen L, Green K.et al Capacity for community development: an approach to conceptualization and measurement. J Community Dev Soc 200132251–270. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith C, Raine K, Anderson D.et al A preliminary examination of organizational capacity for heart health promotion in Alberta's regional health authorities. Promot Educ 2001(suppl 1)40–43. [PubMed]

- 20.Naylor P, Wharf‐Higgins J, O'Connor B.et al Enhancing capacity for cardiovascular disease prevention: an overview of the British Columbia heart health dissemination project. Promot Educ 2001(suppl 1)44–48. [PubMed]

- 21.Elliott S, Taylor S, Cameron S.et al Assessing public health capacity to support community‐based heart health promotion: the Canadian heart health initiative, Ontario Project (CHHIOP). Health Educ Res 199813607–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley B, Taylor M, Elliott S. Determinants of implementing heart health promotion activities in Ontario public health units: a social ecological perspective. Health Educ Res 200116425–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebbesen L, Health S, Naylor P.et al Issues in measuring health promotion capacity in Canada: a multi‐province perspective. Health Promot Int 20041985–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson D, Plotnikoff R, Raine K.et al Towards the development of scales to measure “will” to promote health heart within health organizations in Canada. Health Promot Int 200419471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett L, Plotnikoff R, Raine K.et al Development of measures of organizational leadership for health promotion. Health Educ Behav 200532195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canadian Heart Health Initiative – Ontario Project (CHHIOP) Survey of capacities, activities, and needs for promoting heart health 1997

- 27.Saskatchewan Heart Health Program Health promotion contact profile. Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan, 1998

- 28.Lusthaus C, Adrien M ‐ H, Anderson G.et alEnhancing organizational performance: a toolbox for self‐assessment. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, 1999

- 29.Alberta Heart Health Project Health promotion capacity survey. Edmonton: University of Alberta, 2000

- 30.Alberta Heart Health Project Health promotion individual capacity survey: self‐assessment. Edmonton: University of Alberta, 2001

- 31.Alberta Heart Health Project Health promotion organizational capacity survey: self‐assessment. Edmonton: University of Alberta, 2001

- 32.British Columbia Heart Health Project (BCHHP) Revised activity scan. Vancouver: HeartBC 2001

- 33.Nathan S, Rotem S, Ritchie J. Closing the gap: building the capacity of non‐government organizations as advocates for health equity. Health Promot Int 20021769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ontario Heart Health Project Survey of public health units, 2003

- 35.Heart Health Nova Scotia Measuring organizational capacity for heart health promotion: SCAN of community agencies. Halifax: Dalhousie University, 1996

- 36.Heart Health Nova Scotia Capacity for heart health promotion questionnaire – organizational practices. Halifax: Dalhousie University, 1998

- 37.Vallerand R J. Toward a methodology for the transcultural validation of psychological questionnaires: implications for research in the French language. Can Psychol 198930662–680. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross‐cultural adaptation of health‐related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 1993461417–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabachnick B G, Fidell L S.Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2001

- 40.Cattell R B. The Scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behav Res 19661245–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Streiner D L. Figuring out factors: the use and misuse of factor analysis. Can J Psychiatry 199439135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hatcher L, Stepanski E J.A step‐by‐step approach to using the SAS system for univariate and multivariate statistics. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 1994

- 43.Cronbach L J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 195116297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clark L A, Watson D. Constructing validity: basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol Assess 19957309–319. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled agreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 196870213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steckler A, Goodman R M, Alciati M H. Collecting and analyzing organizational level data for health behaviour research (editorial). Health Educ Res. 1997;12: i–iii, [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Reich M R. Public‐private partnerships for public health. Nat Med 20006617–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gordon W A, Brown M. Building research capacity: the role of partnerships. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 200584999–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Podsakoff P M, Organ D W. Self‐reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J Manage 198612531–544. [Google Scholar]