Abstract

Background

Although children are at the greatest risk for medication errors, little is known about the overall epidemiology of these errors, where the gaps are in our knowledge, and to what extent national medication error reduction strategies focus on children.

Objective

To synthesise peer reviewed knowledge on children's medication errors and on recommendations to improve paediatric medication safety by a systematic literature review.

Data sources

PubMed, Embase and Cinahl from 1 January 2000 to 30 April 2005, and 11 national entities that have disseminated recommendations to improve medication safety.

Study selection

Inclusion criteria were peer reviewed original data in English language. Studies that did not separately report paediatric data were excluded.

Data extraction

Two reviewers screened articles for eligibility and for data extraction, and screened all national medication error reduction strategies for relevance to children.

Data synthesis

From 358 articles identified, 31 were included for data extraction. The definition of medication error was non‐uniform across the studies. Dispensing and administering errors were the most poorly and non‐uniformly evaluated. Overall, the distributional epidemiological estimates of the relative percentages of paediatric error types were: prescribing 3–37%, dispensing 5–58%, administering 72–75%, and documentation 17–21%. 26 unique recommendations for strategies to reduce medication errors were identified; none were based on paediatric evidence.

Conclusions

Medication errors occur across the entire spectrum of prescribing, dispensing, and administering, are common, and have a myriad of non‐evidence based potential reduction strategies. Further research in this area needs a firmer standardisation for items such as dose ranges and definitions of medication errors, broader scope beyond inpatient prescribing errors, and prioritisation of implementation of medication error reduction strategies.

Keywords: medication errors, paediatrics, epidemiology

The Institute of Medicine report To Err Is Human shone a spotlight on preventable medical errors and since the release of the report patient safety has become the pre‐eminent issue for health care.1 With our understanding of the problems and solutions for patient safety growing daily, it has become clear that the prescribing, dispensing, and administration of medications represent a substantial portion of the preventable medical errors that occur with children and that children are more at risk for medication errors than adults.2,3

Despite the awareness that children are at increased risk for medication errors, little is known about the epidemiology of these errors and where the gaps remain in our present knowledge. We conducted a systematic literature review to synthesise all the peer reviewed knowledge on medication errors for children published since the release of the To Err Is Human report.1 Our scope included all care settings and all types of medications. In addition, we synthesised all the recommendations to improve paediatric medication safety from national entities and evaluated the paediatric evidence provided to support these recommendations for effectiveness, efficacy, cost effectiveness, feasibility, appropriateness in different settings and institutional barriers.

Methods

Study inclusion criteria for systematic literature review on medication errors

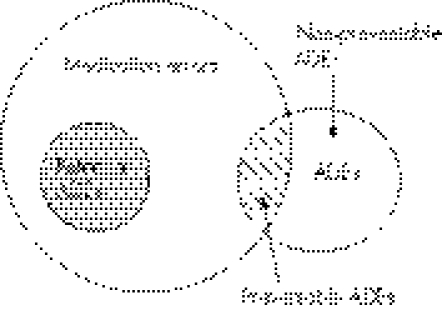

Articles eligible for inclusion in our synthesis had to report peer reviewed English language original data on the epidemiology of medication errors in children published between 1 January 2000 and 30 April 2005. Medication errors were defined as any preventable error in the medication administration process starting from prescribing and including preparing, dispensing, administering, monitoring the patient for effect, and transcribing (eg, medication administration record (MAR)). We only included adverse drug events (ADEs) that were described by the studies as either preventable or having significant potential for harm to the patient (fig 1).2

Figure 1 Relationship between medication errors, potential adverse drug events (ADEs), and ADEs.4

Search strategy for systematic literature review on medication errors

We completed searches of PubMed, Embase and Cinahl in April 2005. The search strategy combined terms for the population (eg, paediatric) and terms to identify articles dealing with medication errors (eg, medication errors as Medical Subject Heading, preventable adverse event) (Appendix 1, available at http://qshc.bmj.com/supplemental). References for all eligible articles were also reviewed. The search results were tracked in a database created in the bibliographic software ProCite (ISI, Berkley, California, USA).

Two independent non‐blinded reviewers screened the title and abstract of each article to determine eligibility. At the full‐text level, two non‐blinded reviewers screened articles and, if the article was eligible, extracted relevant information in a sequential fashion so that the second reviewer was able to see the extraction results from the first reviewer. All reviewers had either clinical degrees or health services research degrees with experience in systematic reviews. All reviewer pairings at all stages of this effort included at least one clinician, and the reviewer pairings for the abstracts were kept for the full text review. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus between the two reviewers after discussion. We developed and pilot tested forms to extract information such as duration of the study, type of study, the incidence of medication errors and information about the medication errors studied, such as the type and severity (Appendix 2, available at http://qshc.bmj.com/supplemental). Evidence tables summarising the information from the articles were created from the spreadsheets and we qualitatively synthesised the literature since no articles included comparable numerators, denominators, or definitions for medication error that would have permitted quantitative synthesis of the articles.

Synthesis of recommendations to reduce medication errors for children

Working in conjunction with the Institute of Medicine, we identified national entities that have created and disseminated recommendations to improve medication safety either specifically for children or more broadly for all patients. These entities were: Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group, American Hospital Association, American Academy of Pediatrics/National Initiative for Children's Healthcare Quality, Institute of Medicine, National Quality Forum, Massachusetts Hospital Association/Massachusetts Coalition for the Prevention of Medical Errors, National Coordinating Council for Medication errors Reporting and Prevention, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.1,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 We reviewed all the published recommendations from these bodies and any cited literature to support the recommendations to determine whether this literature included, or was specific for, children.

Results

Literature search for systematic review on medication errors

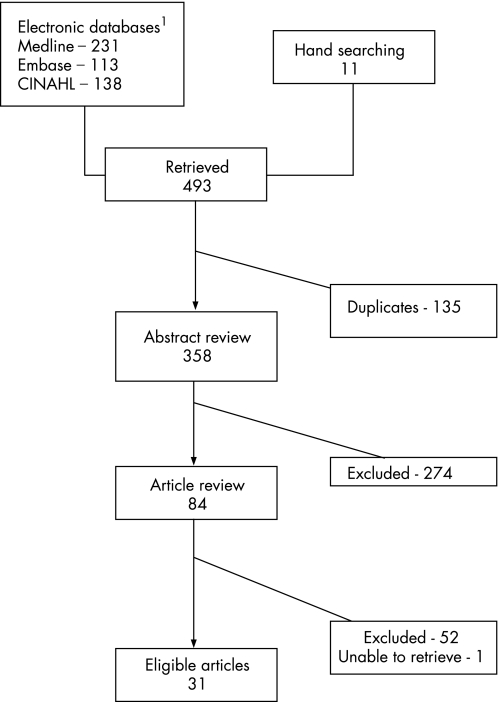

Our search identified 358 articles. Eight‐four (23%) of these articles were deemed eligible through the title and abstract screening. The most common reason for excluding an article from further consideration was lack of original data. A further 52 articles were excluded during the full‐text review, and we were unable to retrieve one article, leaving 31 articles for full text data extraction.23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53 Figure 2 provides an overview of the search and screening process (Appendix 3 lists the articles excluded, available at http://qshc.bmj.com/supplemental).

Figure 2 Summary of search and review process.

Systematic literature review on medication errors

Study characteristics

Design

Table 1 details the characteristics of the 31 studies. Twenty‐three of the 31 studies occurred within single institutions and 21 included data from a ⩽1 year period, with the minimum time period being 1 week. Twenty‐two of the studies evaluated paediatric inpatients, five studies were focused on either ambulatory clinics or emergency departments and three studies evaluated the home setting. Eighteen of the studies evaluated all medications able to be dispensed in that care setting, whereas 13 studies focused on only a subset of medications (table 1).

Table 1 Summary of article characteristics.

| Citation | Type of study | Setting | Type of medication studied | Type of numerator | Type of denominator | How were data obtained | Types of errors collected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simpson et al23 | Interventional | ICU patients only | All types | Patient days | Incident/error reports | All types | |

| Petridou et al25 | Retrospective review without controls | Clinic or outpatient | Vaccines | Medication errors | Time period (2 years) | Incident/error reports | All types |

| Cimino et al28 | Interventional | ICU patients only | All types | Adverse drug events and medication errors | Manual medication orders | Chart reviews | All types |

| Butte et al41 | Cohort | Immunisations | Medication errors | Manual medication orders and patients | Chart reviews | All types | |

| Marino et al43 | Cohort | Inpatient | All types | Medication errors | Manual medication orders and patient days | Chart reviews | All types |

| Cote et al45 | Inpatient and outpatient | Sedatives for procedures | Medication errors | Manual error reports | Incident/error reports, solicited case reports | All types | |

| Upperman et al47 | Interventional | Inpatient | All types | Adverse drug events | Per 1000 doses dispensed | Incident/error reports | All types |

| Slonim et al50 | Retrospective review without controls | Inpatient | All types | ICD9 code 995.2! | Admissions | Administrative data (ICD9 codes) | All types |

| Cowley et al48 | Incident report/case series review | Inpatient | All types | Medication errors | Computerised error reports | Incident/error reports from MER and MedMARx | All types and administering |

| Potts et al30 | Interventional | ICU patients only | All types | Adverse drug events and medication errors | Manual medication orders | Chart reviews | All types and prescribing |

| Holdsworth et al35 | Retrospective chart reviews and staff interviews | Inpatient | All types | Preventable ADEs*as determined by authors and potential ADEs* | Patient days, admissions and medical record evidence of ADE*: excluded errors corrected before medication put into MAR | Chart reviews and interviews | All types, prescribing and dispensing |

| Sangtawesin et al31 | Retrospective review without controls | Inpatient | All types | Medication errors | Admissions | Incident/error reports | All types, prescribing, dispensing and administering |

| Frey et al38 | Incident report/case series review | ICU patients only | All types | Medication errors | Manual error reports | Incident/error reports | All types, prescribing, dispensing, administering and MAR/documentation |

| Kaushal et al42 | Cohort | Inpatient | All types | ADEs and medication errors | Manual medication orders, patient days and admissions | Chart reviews | All types, prescribing, dispensing, administering, monitoring patient for effect and MAR/documentation |

| Derrough and Kitchin37 | Incident report/case series review | Mix | Vaccines | Inadvertent vaccine administration | Prospective inquiries of inadvertent admission of vaccines: calls by providers to pharmaceutical company information service | Incident/error reports | Administering |

| Li et al44 | Cross sectional | Home | Paracetamol and ibuprofen | Medication errors | Patients ⩽10 receiving paracetamol or ibuprofen at home in past 24 hours | Survey to parents | Administering |

| Losek46 | Retrospective review without controls | Emergency department | Paracetamol administered by emergency department staff | Medication errors | Patients | Chart reviews | Administering |

| Feikema et al51 | Cross sectional | Clinic or outpatient | Vaccines | Extra immunisations | Patients | Chart reviews from National Immunisation Survey screenings | Administering |

| Goldman and Scolnik52 | Cross sectional parental interview | Home | Paracetamol administered by parents at home | Medication errors | Patients | Interviews | Administering |

| McErlean et al53 | Cross sectional parental interview | Home | Antipyretic drugs administered by parent at home | Medication errors | Patients | Interviews | Administering |

| Parshuram et al32 | Prospective observational | ICU patients only | Morphine infusion | Discrepancies between ordered and measured concentrations | Number of infusions | Liquid chromatography | Dispensing |

| Cable and Craft26 | Retrospective review without controls | Inpatient | All types | Disagreement of Cardex with order | Manual medication orders | Chart reviews | MAR/documentation |

| Lehmann et al27 | Interventional | ICU patients only | TPN | Medication errors | Manual medication orders (TPN) | Order review | Prescribing |

| Cordero et al29 | Interventional | ICU patients only | Gentamicin | Medication errors | VLBW infants born consecutively 6 months before CPOE receiving drug | Chart reviews and medical records | Prescribing |

| Lesar36 | Incident report/case series review | Inpatient | All types | Medication errors | Computerised error reports, patient days and admissions identified by pharmacists and entered into relational database | Incident/error reports | Prescribing |

| Farrar et al49 | Interventional study | Inpatient | All types | Medication errors | Computerised medication orders | Chart reviews | Prescribing |

| Fontan et al34 | Cohort | Inpatient | All types | Medication errors | Manual medication orders and computerised medication orders | Chart reviews | Prescribing and administering |

| Kozer et al39 | Retrospective review without controls | Emergency department | All types | Medication errors | Manual medication orders | Chart reviews | Prescribing and administering |

| Pichon et al40 | Retrospective review with controls | Inpatient | All types | Medication errors | Manual medication orders | Chart reviews | Prescribing and MAR/Documentation |

| France et al24 | Incident report/case series review | Inpatient | Chemotherapy only | Medication errors | Computerised error reports | Incident/error reports | Prescribing, dispensing, administering and MAR/documentation |

| King et al33 | Interventional | Inpatient | All types | Adverse drug events and medication errors | Manual error reports | Incident/error reports | Prescribing, dispensing, administering and MAR/documentation |

ADE, adverse drug event; CPOE, computerised physician order entry; ICU, Intensive care unit; MAR, medication administration record; MedMARx, United States Pharmacopeia database designed to reduce medication errors in hospitals; MER: medication errors reporting programme submitted to United States Pharmacopeia; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; VLBW, very low birth weight.

*ADEs are defined as having the potential to produce significant injury, includes errors detected before drug administration as well as errors that did not produce significant adverse consequences, excludes errors that were identified and corrected before the medication was entered into MAR.

†ICD9, International Classification of Disease, 9th edition. Public Health Service and Health Care Financing Administration. International classification of diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification. Vols 1, 2, and 3; eighth edition. Washington, DC: Public Health Service; 1997.

‡Code 995.2: adverse effect/allergic reaction/hypersensitivity/idiosyncrasy of drug, medicinal and biological substance (due) to correct medicinal substance properly administered.

Overall the numerator data reported was described as or was consistent with “medication errors” in 25 studies, “ADEs” in 1 study, and 5 studies reported both medication errors and ADEs. The types of medication errors reported included prescribing errors (n = 14), dispensing errors (n = 7), administering errors (n = 14), monitoring patient for effects errors (n = 1), MAR errors (n = 7), and overall lumping of all of these error types (n = 14). There was non‐uniformity in the definitions used, if they were explicitly stated, for medication errors. For example, one study defined an error as only those orders with a 10‐fold dosing error and another defined medication errors as only those with >10% deviation from recommended dose. These differences are detailed in tables 3–8 under numerator and numerator description columns.

Table 3 Prescribing error results summary.

| Citation | Numerator and numerator description | Denominator and denominator description |

|---|---|---|

| France et al24 | 71 Chemotherapy ordering errors: includes dosing, omission and wrong date errors | 97 Electronically reported chemotherapy errors in 13 months |

| Lehmann et al27 | 60 TPN errors that required pharmacist to contact provider: includes osmolality problems, insufficient fluid, calculation errors, omissions | 557 TPN orders in 1.5 months |

| Cordero et al29 | 14 Gentamicin prescription dosage errors: prescribed dose >10% deviation from recommended dose 5 Gentamicin overdoses: >10% overdose 9 Gentamicin underdoses: >10% underdose | 105 VLBW infants born consecutively 6 months before CPOE receiving drug |

| Potts et al30 | 2049 Medication prescribing errors: includes weight not available, missing information | 6803 Manual PICU orders in 2 months |

| Sangtawesin et al31 | 114 Prescribing errors: includes wrong dose, wrong choice, known allergy and others | 32105 Admissions in 14 months |

| King et al33 | 13 Prescribing medication errors | 416 Medication errors in 3 years |

| Fontan et al34 | 937 Prescribing errors: includes any error in the prescription of drug's name, form, dosage, route, any omission of these prescribing items including prescriber's name and any drug interaction. | 4532 Prescribed drugs in 2 months |

| 419 Computerised prescribing errors as defined above | 3943 Computerised prescribed drugs in 2 months | |

| 518 Hand written prescribing errors | 589 Hand written prescribed drugs in 2 months | |

| 44 Wrong form errors 19 Wrong route errors 47 Wrong dosage errors 34 Wrong dosage form errors 587 Omission errors 152 “Caution” drug interactions 0 “Contraindicated” and “not advised” drug interactions | 4532 Prescribed drugs in 2 months | |

| Holdsworth et al35 | 35 Preventable ADEs that were underdose, wrong dose and overdose: preventable was determined by authors | 46 Preventable ADEs in 8 months |

| 39 Potential ADEs* that were underdose and overdose | 94 Potential ADEs* in 8 months as defined above | |

| Lesar36 | 39 Prescribing errors occurring in paediatric patients: all errors were prevented before reaching patient | 200 Error reports identified by pharmacists and entered into a relational database in 6 months |

| 0.53 10‐Fold error rate in paediatric patients | Per 100 admissions, recorded over 6 months | |

| 0.98 10‐Fold error rate in paediatric patients | Per 1000 patient days, recorded over 6 months | |

| Frey et al38 | 102 Overall prescribing errors 9 Illegible errors 37 Calculation errors 22 Wrong unit errors (eg ml instead of mg) | 275 Error reports in 2001 |

| Kozer et al39 | 154 Prescribing errors 117 Wrong frequency errors 133 Wrong dose errors 5 Wrong drug errors 7 Wrong route errors | 1532 Charts reviewed in 12 randomly selected days in summer |

| Pichon et al40 | 76 Incomplete non‐chemotherapy orders defined as omissions: number of doses missing, route missing, dose missing 89 Non‐chemotherapy order omissions: more than one omission possible in a single order | 198 Non‐chemotherapy orders |

| 19 Omissions on non‐chemotherapy PRN¥ orders | 22 Non‐chemotherapy PRN¥ orders | |

| Kaushal et al42 | 454 Physician ordering medication errors 91 Physician ordering potential ADEs*: defined as errors with significant potential for injuring patient | 10 778 Orders, 1120 admissions and 3932 patient days in 6 weeks |

| Farrar et al49 | 29 Prescribing errors for non‐paediatricians for orders reviewed | 38 Non‐paediatricians' orders reviewed |

| 17 Prescribing errors for paediatricians for orders reviewed | 65 Paediatricians' orders reviewed |

ADE, adverse drug event; CPOE, computerised physician order entry; MAR, medication administration record; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit; PRN, drug administered as required; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; VLBW, very low birth weight.

*Potential ADE defined as having the potential to produce significant injury, includes errors detected before drug administration as well as errors that did not produce significant adverse consequences, excludes errors that were identified and corrected before the drug was entered into MAR.

Table 4 Dispensing error results summary.

| Citation | Numerator and numerator description | Denominator and denominator description |

|---|---|---|

| France et al24 | 9 Preparation chemotherapy errors | 97 Electronically reported chemotherapy errors in 13 months |

| Sangtawesin et al31 | 112 Dispensing errors | 32 105 Admissions in 14 months |

| Parshuram et al32 | 150 Discrepancies of >10% between ordered and measured infusions of morphine 13 Twofold or greater discrepancy between ordered and measured infusions of morphine | 232 Infusions in 7 months |

| King et al33 | 19 Dispensing errors | 416 Medication errors in 3 years |

| Holdsworth et al35 | 39 Number of dispensing potential ADEs* | 94 Potential ADEs* in 8 months |

| Frey et al38 | 162 Dispensing errors | 275 Error reports in 2001 |

| Kaushal et al42 | 6 Pharmacy dispensing medication errors 4 Pharmacy dispensing potential ADEs*: defined as errors with significant potential for injuring patient | 10 778 Orders, or 1120 admissions, or 3932 patient days in 6 weeks |

ADE, adverse drug event; MAR, medication administration record.

*Potential ADE defined as having the potential to produce significant injury, includes errors detected before drug administration as well as errors that did not produce significant adverse consequences, excludes errors that were identified and corrected before the drug was entered into MAR.

Table 5 Administering error results summary.

| Citation | Numerator and numerator description | Denominator and denominator description |

|---|---|---|

| France et al24 | 13 Administering chemotherapy errors | 97 Electronically reported chemotherapy errors in 13 months |

| Sangtawesin et al31 | 49 Administering errors: includes wrong time, omission error, wrong strength, unauthorised drug, wrong patient, extra dose, wrong route, wrong dosage form | 32105 Admissions in 14 months |

| King et al33 | 314 Administering errors | 416 Medication errors in 3 years |

| Fontan et al34 | 1077 Administering errors defined as any deviation between prescribed and administered drugs: includes extra/omitted dose, wrong route, wrong time and patient non‐compliant 57 Extra dose errors 454 Dose omission errors 17 Wrong dose errors 2 Wrong route errors 8 Patient non‐compliant errors 539 Wrong time errors | 4589 Opportunities for administering errors: the sum of administered drugs and omitted drugs in 2 months |

| Derrough and Kitchin37 | 161 Inadvertent administration of vaccine to children: includes out of schedule according to the national recommendations, error in reconstitution of vaccine or diluent used, vaccine given at inappropriate age, inappropriate interval between vaccines, wrong vaccine (eg DTP for DT), expired vaccine, vaccine contraindicated. From pharmaceutical company telephone‐based vaccine information service | 302 Inadvertent vaccine administrations (all age groups) in 1 year |

| Frey et al38 | 200 Administering errors | 275 Error reports in 2001 |

| Kozer et al39 | 59 Administering errors | 1532 Charts reviewed in 12 randomly selected days in summer |

| Kaushal et al42 | 78 Nurse administering medication errors 5 Nurse administering potential ADEs*: defined as errors with significant potential for injuring patient | 10 788 Orders, 1120 admissions and 3932 patient days in 6 weeks |

| Li et al44 | 87 Incorrect paracetamol doses at home 66 Paracetamol underdoses at home 21 Paracetamol overdoses at home 6 Paracetamol doses given more frequently than 4 hours at home | 140 Patients who received home administrations of paracetamol in past 24 hours, recorded over 3 months |

| 19 Incorrect ibuprofen doses at home 9 Ibuprofen underdoses at home 10 Ibuprofen overdoses at home 28 Ibuprofen doses given more frequently than 6 hours at home | 74 Patients who received home administrations of ibuprofen in past 24 hours, recorded over 3 months | |

| Losek46 | 34 Paracetamol doses outside standing orders of 10–15 mg/kg | 156 Emergency department patients receiving paracetamol in 1 week |

| Cowley et al48 | 1007 Administering errors submitted to MedMARx database | 1956 Paediatric errors with phase of error indicated submitted to MedMARx in 2 years |

| Feikema et al51 | 4789 Patients overimmunised for at least one vaccine | 22806 Paediatric patients in 1997 |

| Goldman and Scolnik52 | 26 Paracetamol overdoses at home: defined as >10–15 mg/kg 87 Paracetamol underdoses at home: defined as<10–15 mg/kg | 213 Patients who received home administrations of paracetamol recorded over 3 months |

| McErlean et al53 | 53 Incorrect doses of antipyretic drug at home compared with recommended dose | 118 Patients who received home administration of antipyretic drugs |

ADE, adverse drug event; DT, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids vaccine; DTP, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and cellular pertussis vaccine; MedMARx: United States Pharmacopeia database designed to reduce medication errors in hospitals.

Table 6 MAR documentation error results summary.

| Citation | Numerator and numerator description | Denominator and denominator description |

|---|---|---|

| France et al24 | 3 Chemotherapy transcription errors | 97 Electronically reported chemotherapy errors in 13 months |

| Cable and Craft26 | 109 Disagreement with Cardex 49 Major causes of disagreement: different dose, wrong medication, wrong frequency or duration, missing route 39 Orders not on Cardex | 540 Randomly selected paediatric medication orders drawn from over 2 years |

| Sangtawesin et al31 | 46 “Order processing” errors | 32 105 Admissions in 14 months |

| King et al33 | 70 Transcription errors | 416 Reported medication errors in 3 years |

| Frey et al38 | 58 Errors in transcription of physicians order onto medication chart | 275 Error reports in 2001 |

| Pichon et al40 | 41 Non‐chemotherapy transcription errors | 198 Non‐chemotherapy orders |

| 16 Chemotherapy transcription errors | 135 Chemotherapy orders | |

| Kaushal et al42 | 85 Documentation medication errors 9 Documentation potential ADEs: defined as errors with significant potential for injuring patient | 10 778 Orders, or 1120 admissions, or 3932 patient days in 6 weeks |

ADE, adverse drug event.

Table 7 Monitoring for effect error results summary.

| Citation | Numerator and numerator description | Denominator and denominator description |

|---|---|---|

| Kaushal et al42 | 4 Monitoring medication errors; 0 Monitoring potential ADEs defined as errors with significant potential for injuring patient | 10 778 Orders, or 1120 admissions, or 3932 patient days in 6 weeks |

ADE, adverse drug event.

Table 8 Approaches recommended to reduce medication errors in paediatric.

| Approaches to reduce medication errors | Entities supporting approach (reference citations at end of table) | Based on published effectiveness evidence specific for children? | Alternative processes used to support approach | Efficacy, cost, feasibility, appropriateness in different settings, barriers data available for children? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Computerised provider order entry | PPAG, ISMP, AHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| AHRQ report | No | Adult data | No | |

| AAP/NICHQ | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| IOM report | No | Adult data | No | |

| NQF | No | Adult data | No | |

| MHA | No | Adult data | No | |

| NCC MERP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| AAP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 2. Automated dispensing devices | ISMP, PPAG, AHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| AHRQ report | No | Adult data | No | |

| 3. Paediatric presence with formulary management | ISMP, PPAG, AHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| AAP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 4. Appropriate and competent pharmacy personnel and environment | ISMP, PPAG, AHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| NQF | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NCC MERP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| AAP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 5. Pharmacist available “on call” when pharmacy is closed | ISMP, PPAG | No | Expert opinion | No |

| AHA | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| MHA | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 6. Policies on verbal orders | ISMP, PPAG, AHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| JCAHO | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NQF | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NCC MERP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| AAP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 7. Clear and accurate labelling of medications | ISMP, PPAG, AHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| NQF | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NCC MERP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 8. Quality improvement efforts with drug use evaluation and medication error reporting and review | ISMP, PPAG, AHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| MHA | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NCC MERP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| AAP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 9. Healthcare workers have access to current clinical information and references | ISMP, PPAG, AHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| IOM report | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| MHA | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NCC MERP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| AAP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 10. Emergency medication dosage calculation tools | ISMP, PPAG | No | Expert opinion | No |

| 11. Accurate documentation of medication administration | ISMP, PPAG | No | Expert opinion | No |

| MHA | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NCC MERP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 12. Medication standardisation and appropriate storage | ISMP, AHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| IOM report | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| JCAHO | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NCC MERP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 13. Training of all healthcare providers in appropriate medication prescribing, labelling, dispensing, monitoring, and administration | ISMP, PPAG | No | Expert opinion | No |

| IOM report | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| JCAHO | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NQF | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| MHA | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NCC MERP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| AAP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 14. Patient education on drugs | ISMP, AHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| IOM report | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| MHA | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NCC MERP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| AAP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 15. Direct participation of pharmacists in clinical care | AHRQ report | No | Some studies | No |

| IOM report | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NQF | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 16. Computer detection/alert systems for adverse drug events | AHRQ report | No | Some studies | No |

| 17. Reducing adverse drug events related to anticoagulants | AHRQ report | No | Some studies | No |

| 18. Unit dose drug distribution systems | AHRQ report | No | Some studies | No |

| AHA | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NQF | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| MHA | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 19. Special procedures and written protocols for high alert drugs | AHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| IOM report | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| NQF | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| JCAHO | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| MHA | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 20. Use pharmaceutical software | IOM report | No | Expert opinion | No |

| MHA | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 21. Pharmacy‐based IV admixture systems | MHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| 22. Use of bar coding for medication administration | MHA | No | Expert opinion | No |

| NCC MERP | No | Expert opinion | No | |

| 23. Standardise equipment (e.g., pumps, weight scales) | AAP | No | Expert opinion | No |

| 24. Standardise measurement systems (kilograms) | AAP | No | Expert opinion | No |

| 25. Standardise order sheets to include areas for weight and allergies | AAP | No | Expert opinion | No |

| 26. Encourage team environment for review of orders among nurses, pharmacists, prescribers | AAP | No | Expert opinion | No |

PPAG, Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group4,5,6; ISMP, Institute for Safe Medication Practices4,5,6; AHA, American Hospital Association7,8; AAP/NICHQ, American Academy of Pediatrics/National Initiative for Children's Healthcare Quality9,10,11,12; IOM, Institute of Medicine1; NQF, National Quality Forum13,14; MHA, Massachusetts Hospital Association/Massachusetts Coalition for the Prevention of Medical Errors15,16; NCC MERP, National Coordinating Council for Medication errors Reporting and Prevention17,18; AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality19,20; JCAHO, Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.21,22

Denominator data

The denominator data were equally non‐uniform among the studies. The possible denominators included: manual (paper‐based) error reports, computerised error reports, manual medication orders, computerised medication orders, patient days, number of admissions, and time periods. Furthermore, many studies had very narrowly defined denominators, such as number of total parenteral nutrition orders or patients <10 years of age who received paracetamol or ibuprofen in the past 24 hours.

Source of data collection

The majority of the overall data was collected by either chart reviews (n = 14) or incident/error reports (n = 11). Although studies that used incident/error reports cannot be used to assess overall epidemiology of medication errors in children, we included them in order to provide insight into the distributional epidemiology of types of medication errors seen in children.

Overall medication error results from systematic literature review

Fourteen of 31 studies reported overall medication error data that included the entire spectrum from prescribing through to monitoring patient for effect. Table 2 gives the results of these studies. Of these, seven reported broad estimates of overall medication error rates in all children based on actual or estimated data using denominators such as patient days, admissions, or orders as opposed to evaluating only medication error reports (Simpson 200423; Cimino 200428; Potts 200430; Sangtawesin 200331; Holdsworth 200335; Kaushal 200142; Marino 200043). Using the studies, the results showed a range of estimated medication errors per medication orders from 5% to 27% based on three studies with similar numerators and denominators that allow consideration together (Cimino 200428; Kaushal 200142; Marino 200043).

Table 2 Summary of studies with overall medication error results.

| Citation | Numerator and numerator description | Denominator and denominator description |

|---|---|---|

| Simpson et al23 | 24.1 Mean monthly medication errors, includes prescribing and administration errors | Per 1000 neonatal activity days, recorded over 3 months |

| Petridou et al25 | 11 Estimated incidence of errors in prescribing, dispensing, administering immunisations based on assumption of 100 000 children born in Greece each year and each child gets 10 immunisations: from National Poison Control Registry with estimated 47 000 calls a year over 2 year period | Per 1 000 000 immunisation doses, recorded over 2 years |

| 40 Immunisation errors reported from National Poison Control Registry 12 Wrong route (eg OPV given IM¶ errors reported from National Poison Control Registry 13 Overdose errors reported from National Poison Control Registry 6 DTP instead of DT administered errors reported from National Poison Control Registry 3 Expired vaccine errors reported from National Poison Control Registry 7 Extra dose errors reported from National Poison Control Registry | 47 000 Estimated calls a year, recorded over 2 years | |

| Cimino et al28 | 3259 Orders with errors 1335 Orders with errors excluding missing date/time only 1924 Orders with only time/date errors 16 Preventable ADEs 2249 Low ADE potential (missing information only) | 12 026 Manual PICU orders in 2 weeks |

| Potts et al30 | 147 Potential ADEs*: includes duplicate treatment, inappropriate dose/interval/route, wrong drug, allergy, drug interaction, wrong units 466 Rule violations: includes trailing zeros, abbreviations 2662 Potential ADEs*, medication prescribing errors and rule violations | 6803 Manual PICU orders in 2 months |

| Sangtawesin et al31 | 322 Medication errors | 32 105 Admissions in 14 months |

| Holdsworth et al35 | 46 Preventable ADEs: preventable as determined by authors 94 Potential ADEs* | 1197 Admissions in 8 months |

| 46 Preventable ADEs as defined above 94 Potential ADEs* as defined above | 10 164 Patient days in 8 months | |

| Frey et al38 | 253 Prescription, dispensing and administering errors 93 Dose too high errors, either prescribed, dispensed or administered 55 Drug omitted errors, either prescribed, dispensed or administered 39 Dose too low errors, either prescribed, dispensed or administered 34 Wrong route errors, either prescribed, dispensed or administered 32 Wrong drug errors, either prescribed, dispensed or administered | 275 Error reports in 2001 |

| Butte et al41 | 206 Patients with at least one invalid immunisation | 580 Charts reviewed in 3 months |

| 289 Invalid doses: dose given before minimum recommended age, doses given within the recommended spacing from previous dose, dose given unnecessarily (this means 1 year earlier than required age), live virus vaccine given to close to previous live virus vaccine 98 Invalid doses because given before recommended age 2 Invalid doses because given too close to live virus dose 96 Invalid doses because unnecessary extra dose 105 Invalid doses because too close to previous dose 12 Invalid doses because too young and too close to previous dose | 6983 Immunisation doses given in 3 months | |

| Kaushal et al42 | 616 Medication errors defined as errors in drug ordering, transcribing, dispensing, administering or monitoring 115 Potential ADEs* defined as errors with significant potential for injuring patient 5 Preventable ADEs* defined as ADE* associated with medication error 337 IV medication errors 126 Oral medication errors 46 Inhalation medication errors | 10 778 Orders, 1120 admissions and 3932 patient days in 6 weeks |

| Marino et al43 | 784 Medication errors | 3312 Orders in summer 1995 11 978 Doses in summer 1995 669 Patient days in summer 1995 |

| Cote et al45 | 38 Drug overdoses or local anaesthetic overdoses submitted to the FDA's incident reporting system, cases from USP and case reports from paediatric anaesthesiologists, intensivists, and paediatric emergency medicine specialists 9 Prescribing/transcribing errors as described above | 95 ADE reports for sedations from 1969 to March, 1996 as described in numerator |

| Upperman et al47 | 0.3 ADEs | Per 1000 doses, recorded over 9 months |

| Cowley et al48 | 543 Omission reports submitted to MedMARx database 494 Wrong dose/quantity reports submitted to MedMARx database 253 Wrong time reports submitted to MedMARx database | 2003 Paediatric errors submitted in 2 years |

| Slonim et al50 | 0.13 1988 drug errors based on reported ICD9† code 995.2‡. All results are national estimates, no real numerator and denominator stated 0.09 1991 drug errors as described above 0.07 1994 drug errors as described above 0.03 1997 drug errors as described above | Per 100 paediatric admissions reported nationally |

ADE, adverse drug event; DT, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids vaccine; DTP, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and cellular pertussis vaccine; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; IM, intramuscularly; MAR, medication administration record; MedMARx, United States Pharmacopeia database designed to reduce medication errors in hospitals; OPV, oral polio vaccine given; PICU, paediatric intensive care unit; USP, United States Pharmacopeia.

*Potential ADE defined as having the potential to produce significant injury, includes errors detected before drug administration as well as errors that did not produce significant adverse consequences, excludes errors that were identified and corrected before the drug was entered into MAR.

†ICD9, International Classification of Disease, 9th edition. Public Health Service and Health Care Financing Administration. International classification of diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification. Vols 1, 2, and 3; eighth edition. Washington, DC: Public Health Service; 1997.

‡Code 995.2: adverse effect/allergic reaction/hypersensitivity/idiosyncrasy of drug, medicinal and biological substance (due) to correct medicinal substance properly administered.

Prescribing error results from systematic literature review on medication errors

Fourteen studies reported medication prescribing errors (table 3). These summarised an estimated prescribing error rate per medication orders of 30%, 20%, and 4% from the three studies that used similar numerators and denominators (Potts 200430; Fontan 200334; Kaushal 200142). The first two studies in this estimate appeared to have broader definitions of medication errors, which may explain the higher error rate estimates. For example, both included all types of omissions as a medication error, such as omissions of weight and prescriber's name. Three of the studies reported overall prescribing errors as rates per patient. The estimates from these studies are prescribing errors for each patient of 4–400 per 1000 patients (Sangtawesin 200331; Kozer 200239; Kaushal 200142).

Dispensing error results from systematic literature review on medication errors

Seven studies reported dispensing errors, although the design of the studies was very different (table 4). Looking at the greatest commonality between these studies—namely, those studies based on error reports, the estimates of the percentage of reported errors that are related to dispensing vary widely from 5% to 58% (France 200424; King 200333; Frey 200238).

Administration error results from systematic literature review on medication errors

Fourteen studies reported administration errors for children (table 5). Six of these studies were medication‐specific with two focused on vaccines and four focused on paracetamol and/or ibuprofen only. Of the three studies which were global in scope, nevertheless, variation among the studies in numerator and denominator definitions and methods of data collection made comparisons difficult. Using the one study that defined “total opportunities for administering errors” as the global denominator, the distributional epidemiology of administration errors shows that the majority of these errors involved either dose omissions (42%) or wrong time of administration (50%) (Fontan 200334).

MAR/documentation error results from systematic literature review on medication errors

Seven studies evaluated documentation errors among children (table 6). The estimate of transcription errors from these studies varies from <1% of orders to 20% of orders having a transcription error.

Monitoring the patient for effect error results from systematic literature review on medication errors

Only one study, listed in table 7, reported monitoring a patient for effect errors and estimated, via chart review, that the incidence was four errors per 1000 patients (Kaushal 200142).

Distributional epidemiology of medication error from error reports

Four studies provided data that can be synthesised to understand the distributional epidemiology of medication errors in paediatrics based on error reports (France 200424; King 200333; Lesar 200236; Frey 200238). Such syntheses are difficult because each study location undoubtedly has different safety culture climates. The safety culture will clearly influence who completes error reports, how often they complete error reports, and what types of event are reported. Little is known about how bias in reporting influences the distributional epidemiology of medication errors. Two of these studies provided data on all medications relative to prescribing, dispensing, administering, and documentation errors (King 2003;33 Frey 200238). Between these two studies, the distributional epidemiological estimates of the relative percentages of error types are: prescribing 3–37%, dispensing 5–58%, administering 72–75%, and documentation 17–21%.

Estimates of the severity of medication errors for patients

Only 11 studies categorised medication errors by severity of outcome for the patient (Simpson 200423; France 200424; Cimino 200428; Sangtawesin 200331; Holdsworth 200335; Frey 200238; Kozer 200239; Kaushal 200142; Marino 200043; Upperman 200547; Cowley 200148). Among these studies, however, at least four different scales were used to rank error severity from scales with two categories to scales with nine categories.

Synthesis of recommendations to reduce medication errors for children

We identified a total of 26 unique recommendations for strategies to reduce medication errors from national entities. The recommendations ranged from equipment/software tools, representation of personnel on groups making decisions on paediatric medications, training and competency of personnel, policies, clear labelling, continuous quality improvement efforts, clear and accurate documentation, standardisation, patient education, and teamwork improvement. Table 8 summarises these recommendations and the paediatric specific evidence behind. In short, none of these recommendations was based on published evidence of effectiveness in children. The vast majority of recommendations were based on expert opinion (n = 22), with the remainder being based on studies in adult populations (n = 4). No recommendation had supporting paediatric specific evidence on efficacy, cost effectiveness, feasibility, appropriateness in different settings, and institutional barriers or risks.

Conclusions

Since the Institute of Medicine To Err Is Human report1 a significant amount of research has been done on medication errors in children, and a significant number of recommendations have been made by various entities on how to make medication administration safer for children. There can be no doubt, based on this evidence, that medication errors are a significant percentage of medical errors in children. Our review estimates that 5–27% of medication orders for children contain an error somewhere along the spectrum of the entire delivery process involving prescribing, dispensing, and administering based on three studies (Cimino 200428; Kaushal 200142; Marino 200043). Our review also estimates that there are 100–400 prescribing errors per 1000 patients and highlights that the majority of research to date has focused on the prescribing step of medication delivery (Kozer 200239; Kaushal 200142).

Looking at error reporting systems, it is clear that each step of the medication process is error prone, although the majority of research has focused on prescribing errors. Our evidence based estimates at the overall “share of the pie” that each step contributes to the overall rate of medication errors among children are the following: prescribing 3–37%, dispensing 5–58%, administering 72–75%, and documentation 17–21% (King 200333; Frey 200238).

Overall, our depth of understanding of the epidemiology of paediatric medication errors remains poor. Our systematic literature review on medication errors highlights the fact that estimates of the incidence of medication errors in children are severely hampered by the lack of uniform definitions of medication errors (numerator data) and study population (denominator) among studies and by the different means of data collection used to identify errors.

Also of importance, many studies did not explicitly define medication errors. A recently published report looking only at prescribing errors in children highlighted the great difficulty in defining what a medication error is.54 Barriers to defining medication errors in children and to then being able to measure the epidemiology of medication errors include: off‐label use of medications with dosage ranges extrapolated from adult literature, different recommendations for dosing ranges for the same medication from different sources, and unclear rules as to when adult doses may be appropriate for children. None of the studies looking at all medications with details on prescribing errors stated what the “correct” dosing range was that guided their definitions and data collection.

Focusing on the source of data, the vast majority of studies evaluated in this report relied on either chart review or error reports, with a handful using administrative or registry data. Although each mode of identifying medication errors has strengths and weaknesses and will produce varying results, it seems likely that an ideal error identification system may involve multiple data sources and potentially include triangulation between administrative data, chart review, and voluntary error reports of critical incidents in order to maximise the ability to identify events at each step of the process. Taken alone, each data source has significant limitations for defining the epidemiology of medication errors. Administrative data, as analysed here, are inexpensive, nearly universal, and permit unsolicited identification of potential events, although the depth of clinical information is limited. Chart review, on the other hand, provides in‐depth clinical information but is fairly expensive to implement on a large scale and is limited by what is documented in the chart. Lastly, voluntary critical incident reporting depends completely on the compliance of providers with reporting but does provide real time in‐depth clinical insights. Interdigitated use of these types of data collection would create a system less likely to produce a biased estimate of the epidemiology.

These significant limitations of the examined studies—namely, differing definitions of the numerators and denominators, lack of consistent definition of medication error, less robust and/or narrowly focused methodologies, and the aforementioned short time frames of data collection and single institutional experiences in these studies, make it very difficult, if not impossible, to generalise easily the findings to all healthcare settings. Indeed the vast ranges on some of the results for estimates of different types of medication errors bear testament to this difficulty.

Despite the limitations of the available literature, several key findings warrant discussion and suggest a further national agenda for medication errors in children.

First, standardisation of recommended doses for children is an essential step to enable providers, researchers, and developers of technological solutions for prescribing to speak a common and uniform language on what doses are acceptable and what doses are in error for children. For example, a recent review exploring the limitations of recommended doses for children found a nearly twofold difference in recommended doses of oxycodone, a narcotic, among three widely used references while a fourth reference simply listed no weight‐based dose recommendation.54 In a recently published study on paediatric ambulatory medication errors, one key finding was that no fewer error rates occurred at the one of three sites evaluated that used an electronic prescription writer.55 This last finding was probably due to the absence of paediatric‐specific dosing logic in the electronic prescription writer. Despite the push for computerised order entry and prescribing, the lack of uniform agreement on standard paediatric doses is at least part of the reason for the usual absence of paediatric‐specific dosing tables powering most commercially available computerised order entry tools. Without standard paediatric doses, and requirements that these dosage rules are built into computerised prescribing tools, children will fail to reap the benefit of information technology in the medication delivery process.

Second, standardisation of definitions of medication errors is a clear need at hand. As examples of this problem based on the studies examined here, the range of definitions of medication errors included medications prescribed at >10% of the recommended dose all the way up to medications prescribed at 10‐fold the recommended dose. The vast majority of the articles simply did not describe the details of the definition of a medication error that was used. Comparably, looking at the entire medication delivery system, some articles did not include errors that were detected before they reached the patient, whereas other articles counted these events as errors. This ambiguity about what exactly is a medication error also permits a wide range of severity of errors to be lumped together. For example, some of the studies counted as medication errors orders that were lacking a prescriber's signature. Although this is clearly an error, the magnitude of potential harm to patients is substantially different from that of orders with dosage errors. Without standardised guidance, all these vastly different interpretations of medication errors are lumped together and make elucidation of high priority areas difficult.

Third, despite much work on medication errors in the inpatient setting, our review identified only a handful of research on medication errors in the emergency department, ambulatory care, and home environments. All of these are critical targets for future research.

Fourth, most of the research to date has been skewed on prescribing errors. Our review of error reporting systems' data clearly shows that the medication process steps of dispensing and administering are as error‐prone, if not more so, than prescribing. Understanding the unique risks for children in these two steps is critical in order to understand better which interventions will remedy the risks. Unlike the medication process for adults, these steps for children rely much more heavily on manual compounding of liquid medications and administration to patients who are unable to perform their own medication safety checks. These facts may well make the dispensing and administering of medications more error prone for children than adult patients.

Last, our synthesis of the various medication error reduction strategies recommended by national bodies resoundingly illustrated the lack of paediatric‐specific evidence. However, it is inarguable that many items on the list of reduction strategies do not need multiple clinical trials to prove their impact. High cost or high resource problems such as computerised order entry, automated dispensing devices, and use of bar coding for medication administration clearly do need high quality evidence in order to foster use and, perhaps more importantly, need to have paediatric‐specific evidence. Many other items, on the other hand, are relatively inexpensive, and many even broach on commonsense based on knowledge of human factors. Strategies in this latter category include: paediatric presence on Formulary committees, appropriate and competent pharmacy personnel and environment, policies on verbal orders, and clear and accurate medication labelling. The lack of paediatric‐specific data on these types of recommendations is non‐troubling. Perhaps more troubling is the enormous scope of recommendations coming from numerous official bodies. Such a piecemeal recommendation path leaves most providers unclear about which of the recommendations has a greater priority should they be faced with human or monetary resource limitations. National research and efforts to summarise and endorse recommendations could help care givers prioritise safety efforts and ensure that the most promising strategies of those recommended are broadly implemented first.

In summary, our review of the literature on medication errors in children and on medication error reduction strategies highlights without question that we know medication errors occur across the entire spectrum of prescribing, dispensing and administering and are a significant source of concern for paediatric patients. Furthermore, the research also confirms that medication errors are a significant concern across all settings of care, including within the home. There can be no doubt of the need for greater understanding of all the aspects of medication errors discussed here so that effective interventions and policy can be crafted. This desired understanding, however, needs a firm foundation of standardisation for issues such as dose ranges, definitions of medication errors, and even for prioritisation of implementation of medication error reduction strategies.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by contract M‐150‐IOM‐2005‐001 from the Institute of Medicine. The Institute of Medicine helped design the study and has given approval for publication.

Abbreviations

ADEs - adverse drug events

MAR - medication administration record

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1999

- 2.Kaushal R, Jaggi T, Walsh K.et al Pediatric medication errors: what do we know? What gaps remain? Ambul Pediatr 2004473–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaushal R, Bates D W, Landrigan C.et al Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA 20012852114–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute for Safe Medication Practices http://www.ismp.org/pressroom/PR20020606.pdf (accessed 26 February 2007)

- 5.Web site http://www.ismp.org/PR/PediatricPharmacyGuidelines.htm (last accessed June 17, 2005)

- 6.Levine S R, for the Institute for Safe Medication Practices and the Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group Guidelines for preventing medication errors in pediatrics. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 20016426–442. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Hospital Association http://www.aha.org (accessed 13 February 2007)

- 8.Pathways for medication safety http://www.medpathways.info/medpathways/tools/tools.html (accessed 13 February 2007)

- 9.Berlin C M, McCarver D G, Notterman D A.et al Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting. Pediatrics 1998102428–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lannon C M, Coven B J, Lane France F.et al Principles of patient safety in pediatrics. Pediatrics 20011071473–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorman R L, Bates B A, Benitz W E.et al Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting. Pediatrics 2003112431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Initiative for Children's Healthcare Quality http://www.nichq.org (accessed 13 February 2007)

- 13.National Quality Forum http://www.qualityforum.org (accessed 13 February 2007)

- 14.National Quality Forum Safe practices for better healthcare. 2003. (Document #NQFCR‐05‐03.)

- 15.Massachusetts Coalition for the Prevention of Medical Errors http://www.macoalition.org/publications.shtml (accessed 13 February 2007)

- 16.Massachusetts Coalition for the Prevention of Medical Errors MHA best practice recommendations to reduce medical errors. http://www.macoalition.org/documents/Best_Practice_Medication_Errors.pdf (accessed 13 February 2007)

- 17.National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention http://www.nccmerp.org (accessed 13 February 2007)

- 18.National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention Council recommendation. http://www.nccmerp.org/councilRecs.html (accessed 13 February 2007)

- 19.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality http://www.ahrq.gov (accessed 13 February 2007)

- 20.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Making health care safer: a critical analysis of patient safety practices. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/ptsafety/ (accessed 13 February 2007)

- 21.The Joint Commission http://www.jcaho.org (accessed 13 February 2007)

- 22.The Joint Commission http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/ (accessed 26 February 2007)

- 23.Simpson J H, Lynch R, Grant J.et al Reducing medication errors in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 200489F480–F482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.France D J, Cartwright J, Jones V.et al Improving pediatric chemotherapy safety through voluntary incident reporting: lessons from the field. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 200421200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petridou E, Kouri N, Vadala H.et al Frequency and nature of recorded childhood immunization‐related errors in Greece. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 200442273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cable G, Craft J. Agreement between pediatric medication orders and medication cardex. J Healthc Qual 20042614–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lehmann C U, Conner K G, Cox J M. Preventing provider errors: online total parenteral nutrition calculator. Pediatrics 2004113748–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cimino M A, Kirschbaum M S, Brodsky L.et al Assessing medication prescribing errors in pediatric intensive care units. Pediatr Crit Care Med 20045124–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cordero L, Kuehn L, Kumar R R.et al Impact of computerized physician order entry on clinical practice in a newborn intensive care unit. J Perinatol 20042488–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potts A L, Barr F E, Gregory D F.et al Computerized physician order entry and medication errors in a pediatric critical care unit. Pediatrics 200411359–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sangtawesin V, Kanjanapattanakul W, Srisan P.et al Medication errors at Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health. J Med Assoc Thai 200386(Suppl 3)570–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parshuram C S, Ng G Y, Ho T K.et al Discrepancies between ordered and delivered concentrations of opiate infusions in critical care. Crit Care Med 2003312483–2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.King W J, Paice N, Rangrej J.et al The effect of computerized physician order entry on medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. Pediatrics 2003112506–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fontan J E, Maneglier V, Nguyen V X.et al Medication errors in hospitals: computerized unit dose drug dispensing system versus ward stock distribution system. Pharm World Sci 200325112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holdsworth M T, Fichtl R E, Behta M.et al Incidence and impact of adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 12003 5760–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lesar T S. Tenfold medication dose prescribing errors. Ann Pharmacother 2002361833–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Derrough T F, Kitchin N R. Occurrence of adverse events following inadvertent administration of childhood vaccines. Vaccine 20022153–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frey B, Buettiker V, Hug M I.et al Does critical incident reporting contribute to medication error prevention? Eur J Pediatr 2002161594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kozer E, Scolnik D, Macpherson A.et al Variables associated with medication errors in pediatric emergency medicine. Pediatrics 2002110737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pichon R, Zelger G L, Wacker P.et al Analysis and quantification of prescribing and transcription errors in a paediatric oncology service. Pharm World Sci 20022412–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butte A J, Shaw J S, Bernstein H. Strict interpretation of vaccination guidelines with computerized algorithms and improper timing of administered doses. Pediatr Infect Dis J 200120561–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaushal R, Bates D W, Landrigan C.et al Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA 20012852114–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marino B L, Reinhardt K, Eichelberger W J.et al Prevalence of errors in a pediatric hospital medication system: implications for error proofing. Outcomes Manag Nurs Pract 20004129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li S F, Lacher B, Crain E F. Acetaminophen and ibuprofen dosing by parents. Pediatr Emerg Care 200016394–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cote C J, Notterman D A, Karl H W.et al Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: a critical incident analysis of contributing factors. Pediatrics 2000105805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Losek J D. Acetaminophen dose accuracy and pediatric emergency care. Pediatr Emerg Care 200420285–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Upperman J S, Staley P, Friend K.et al The impact of hospitalwide computerized physician order entry on medical errors in a pediatric hospital. Pediatr Surg 20054057–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cowley E, Williams R, Cousins D. Medication errors in children: a descriptive summary of medication error reports submitted to the United States Pharmacopeia. Curr Ther Res Clin Ex 200162627–640. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farrar K, Caldwell N A, Robertson J.et al Use of structured paediatric‐prescribing screens to reduce the risk of medication errors in the care of children. Br J Healthcare Comput Info Manage 20032025–27. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Slonim A D, LaFleur B, Ahmed W.et al Hospital‐reported medical errors in children. Pediatrics 2003111617–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feikema S M, Klevens R M, Washington M L.et al Extraimmunization among US children. JAMA 20002831311–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldman R D, Scolnik D. Underdosing of acetaminophen by parents and emergency department utilization. Pediatr Emerg Care 20042089–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McErlean M A, Bartfield J M, Kennedy D A.et al Home antipyretic use in children brought to the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 200117249–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McPhillips H, Stille C, Smith D.et al Methodological challenges in describing medication dosing errors in children. In: Henriksen K, Battles J, Marks E, Lewin DI, eds. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation. Vol 2. Concepts and methodology. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005213–223. [PubMed]

- 55.McPhillips H A, Stille C J, Smith D.et al Medication dosing errors in outpatient pediatrics. J Pediatrics 2005147761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]