Abstract

We identified agtA, a gene that encodes the specific dicarboxylic amino acid transporter of Aspergillus nidulans. The deletion of the gene resulted in loss of utilization of aspartate as a nitrogen source and of aspartate uptake, while not completely abolishing glutamate utilization. Kinetic constants showed that AgtA is a high-affinity dicarboxylic amino acid transporter and are in agreement with those determined for a cognate transporter activity identified previously. The gene is extremely sensitive to nitrogen metabolite repression, depends on AreA for its expression, and is seemingly independent from specific induction. We showed that the localization of AgtA in the plasma membrane necessitates the ShrA protein and that an active process elicited by ammonium results in internalization and targeting of AgtA to the vacuole, followed by degradation. Thus, nitrogen metabolite repression and ammonium-promoted vacuolar degradation act in concert to downregulate dicarboxylic amino acid transport activity.

Amino acids can be utilized by saprophytic fungi as nitrogen and/or carbon sources. Their uptake is mediated by transmembrane proteins belonging to the specific fungal YAT (TC 2.A.3.10, yeast amino acid transporter) family, a member of the APC (amino acid polyamine choline) superfamily (25), which shows a wide range of substrate specificities and includes representatives in all realms of life (53). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae (51), 18 YAT transporters have been functionally characterized, while only a few have been studied in other organisms (8, 25, 35, 57, 67, 68, 69, 72, 76; Saccharomyces genome database at http://www.yeastgenome.org/). The YAT family transporters share a common predicted topology, comprising 12 transmembrane domains, and show, even among proteins with completely different substrate specificities, a high degree of sequence identity (2, 25). The transporters of the dicarboxylic amino acids glutamate and aspartate have been characterized in S. cerevisiae (DIP5; 47) and Penicillium chrysogenum (PcDIP5; 68) and are members of this family. In A. nidulans, specific dicarboxylic amino acid transport activity and certain aspects of its regulation were previously reported (24, 26, 42, 51, 52), but the corresponding gene(s) was not characterized.

In fungi, the genes that encode transporters and enzyme activities involved in nitrogen source utilization are subject to tight transcriptional and/or posttranscriptional controls. Preferred nitrogen sources (such as ammonium and glutamine) repress the transcription of genes involved in the utilization of metabolically less favorable nitrogen sources such as nitrate, purines, or amino acids. In A. nidulans, nitrogen metabolite repression acts by inactivating the AreA GATA transcriptional activator (30) by a number of concurring mechanisms (36, 66). In S. cerevisiae, a transcriptional repression mechanism similar but not identical to the one described above for A. nidulans is operative (see reference 33 for a review).

In addition to being subject to transcriptional regulation, amino acid transporters are posttranslationally regulated in response to the available nitrogen source. Stanbrough and Magasanik (60) demonstrated that glutamate, a nonrepressive nitrogen source, leads to reduction of Gap1p (general amino acid permease) activity in S. cerevisiae. Preferred repressive nitrogen sources such as ammonium result in the endocytic downregulation of Gap1p, which is delivered to the vacuole, whereas newly synthesized Gap1p reaches the endosomal system directly from the Golgi (22). Recent work by Risinger and Kaiser underlines the complexity of the posttranslational regulation processes that affects Gap1p, where three distinct ubiquitin-mediated sorting steps have been shown to be involved in the delivery of Gap1p to the vacuole (50 and references therein).

While AreA-dependent nitrogen metabolite repression has been thoroughly studied in A. nidulans, posttranslational inactivation in response to a favored nitrogen source has not been studied in any detail. An ammonium-dependent posttranslational mechanism that results in the sorting of the purine transporters UapC and UapA, which belong to the NAT (nucleobase ascorbate transporter) family (APC superfamily), to the vacuolar lumen has been described (41, 71). Thus, a common and conserved posttranslational nitrogen source-dependent regulatory mechanism that acts at the level of secondary nitrogen source transporters may be present throughout the ascomycetes.

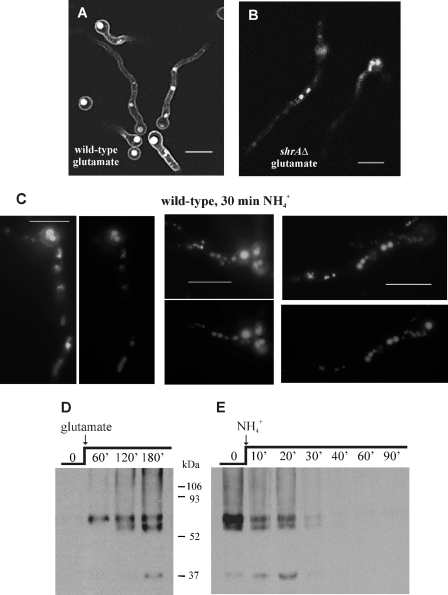

In S. cerevisiae, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Shr3p chaperone is the one and only common sorting factor specific for transporters of the YAT family (31). Shr3p promotes the transfer of YAT proteins from the ER to the Golgi by preventing their aggregation in the ER and their subsequent ER-associated degradation, as well as by recruiting components of the ER to Golgi transport vesicles (28, 31, 34). The orthologue of Shr3p in A. nidulans has a restricted range of targets compared with the S. cerevisiae protein (17). A dicarboxylic amino acid transporter would be a good candidate target, as shrA mutant strains are strongly impaired in the utilization of aspartate and glutamate as nitrogen sources (17; see also Fig. 1).

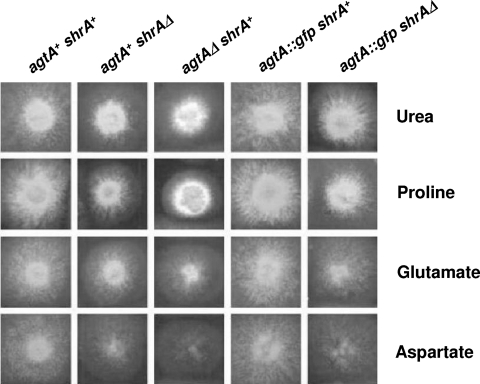

FIG. 1.

A. nidulans strains with different agtA and shrA genetic backgrounds grown on different nitrogen sources (urea, proline, glutamate, and aspartate). The relevant genotypes are indicated above the columns. For the complete genotypes, see Materials and Methods and Table 1. The agtAΔ strain shows almost no growth on aspartate and considerably impaired growth on glutamate. The strains carrying the agtA::sgfp fusion show wild-type growth on aspartate and glutamate. In all shrAΔ strains, the ability to grow on proline, glutamate, and aspartate is impaired in comparison with that of the corresponding shrA+ strains (17).

In this article, we aimed to identify agtA, the gene that encodes the specific dicarboxylic amino acid transporter of Aspergillus nidulans; we carried out a preliminary kinetic characterization of this transporter, and we studied its transcriptional and posttranslational regulation in response to the nitrogen status of the cell. The identification and characterization of this transporter provide a tool to study amino acid transporter localization and trafficking and the interplay of the different regulatory mechanisms involved in nitrogen source utilization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and growth conditions.

The minimal medium (MM) and complete medium (CM) used, as well as the growth conditions for A. nidulans, were described by Cove (11). Supplements were added when necessary at adequate concentrations (http://www.gla.ac.uk/acad/ibls/molgen/aspergillus/supplement.html). Ammonium l(+)-tartrate and urea were used as nitrogen sources at 5 and 10 mM, respectively. Uric acid was used at 600 μM. Amino acids were used at 5 and 10 mM in solid and liquid media, respectively. Aspartate and glutamate were used as monosodium salts (Sigma). Crosses between A. nidulans strains were described by Pontecorvo et al. (45).

For growth tests, conidiospores were inoculated onto solid MM supplemented with the appropriate nitrogen source and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. To monitor steady-state agtA mRNA levels in mycelia, strains were grown on liquid MM for 8 h at 37°C. To assay the role of AreA in agtA expression, mycelia were grown for 7 h at 37°C in the presence of ammonium and then transferred to MM lacking a nitrogen source and incubated for 2 h. To test whether aspartate or glutamate could act as a specific inducer of agtA expression, strains were grown for 7 h at 37°C in the presence of ammonium, urea, or uric acid, and then aspartate or glutamate was added and the cultures were incubated for an additional 2 h at 37°C.

Strains and plasmids. (i) A. nidulans strains.

The different auxotrophic and morphological mutations of A. nidulans strains were compiled by A. J. Clutterbuck (http://www.gla.ac.uk/acad/ibls/molgen/asperfillus/index.html). The strains constructed and used during this work are described in Table 1. In every case, MM indicates medium supplemented with the requirements relevant to the strains used in the experiment.

TABLE 1.

A. nidulans strains constructed and used during this study

| Strain | Genotypea | Description (reference[s]) |

|---|---|---|

| CS2498 | pabaA1 | Wild-type reference strain |

| VS1 | yA2 pantoB100 | Wild-type reference strain |

| CS3095 | areA600 biA1 sb43 | areA null mutant (30) |

| VS4 | xprD1 biA1 pabaA1 | areA mutant with derepressed expression of activities under the control of areA (30, 74) |

| AA1 | pyrG89 biA1 wA3 pyroA4 riboB2 | Recipient strain transformed with the agtA deletion cassette (3) |

| CS1945 | agtAΔ::riboB biA1 pyrG89 wA3 pyroA4 riboB2 | agtA mutant strain (agtAΔ) |

| VS5 | agtA::(sgfp-AfpyrG) xprD1 yA2 biA1 pabaA1 pyroA4 pyrG89 (?) | areA-derepressed mutant carrying sgfp-tagged agtA obtained from the cross of LH115 and VS4 |

| MAD1425 | pyrG89 nkuAΔ::argB pyroA4 argB2 | Recipient strain transformed with the F0agtA-sgfp and agtA-HA fusion cassettes (provided by B. Oakley; 38, 77) |

| LH115 | agtA::(sgfp-AfpyrG) yA2 pyrG89 pabaA1 pyroA4 | Strain carrying an in-locus integration of the F0agtA-sgfp cassette obtained by outcrossing the original transformant |

| LH123 | agtA::(HA-AfpyrG) riboB2 biA1 pyroA4 pyrG89 (?) | Strain carrying an in-locus integration of the agtA-HA cassette obtained by outcrossing the original transformant |

| VS2 | pyrG89 pabaA1 pantoB100 argB2 shrAΔ::pyr4 | shrA mutant strain (shrAΔ) (17) |

| VS3 | agtA::(sgfp-AfpyrG) yA2 pyrG89 pabaA1 pantoB100 pyroA4 shrAΔ::pyr4 | Strain constructed by crossing LH115 with the shrAΔ mutant strain (17) |

AfpyrG is the A. fumigatus pyrG gene.pyrG89 (?) indicates that in outcrossed strains deriving from a primary transformant where pyr4 of Neurospora crassa or AfpyrG is used to complement the pyrG89 mutation ectopically, the status of the resident pyrG locus has not been determined.

(ii) Escherichia coli strains.

The E. coli strains used were JM109b and DH10B.

(iii) Plasmids.

pPL5 carries the riboB gene of A. nidulans (40), pRG3 carries the radish 18S rRNA gene (14), and pl1439 contains the sgfp (a plant-adapted modified version of the green fluorescent protein [GFP] gene [61]) coding sequence and the Aspergillus fumigatus pyrG gene, which complements the pyrG89 mutation of A. nidulans (77). pl1503 contains the HA (hemagglutinin epitope of influenza virus; 21, 39, 75) coding sequence and the pyrG gene of A. fumigatus (kindly provided by E. Espeso). Plasmid pAB1 contains a PCR product corresponding to a 1,649-bp fragment of the agtA gene (positions 249520 to 251169 in supercontig 1.104, lacking 521 bp from the 5′ region of the open reading frame [ORF] and extending up to 199 bp after the stop codon). This fragment was amplified by using as the template genomic DNA of the pabaA1 mutant strain and primers G1 and G2 (5′ TGGTTTCACTGGTTATGC 3′ and 5′ CCTTTGGTTCCGATGTGG 3′, respectively). The amplified fragment was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Transformation methods.

Transformation of E. coli was carried out as described by Sambrook and Russell (54). Transformation of A. nidulans was done as described by Tilburn et al. (65).

DNA manipulations.

Plasmid preparation from E. coli strains was carried out as described by Sambrook and Russell (54) or by using the Qiagen Plasmid Mini and Plasmid Midi kits according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA digestion and cloning strategies were carried out as described by Sambrook and Russell (54). Extraction of genomic DNA from A. nidulans was done as described by Lockington et al. (32). Southern blot analysis was carried out according to Southern (59) and Sambrook and Russell (54). High-fidelity and long-fragment PCRs were carried out with the Expand Long Template PCR system (Roche). Conventional PCRs were carried out with Taq polymerase (Promega). TA cloning was carried out with the pGEM-T Easy vector system (Promega). DNA bands were purified from agarose gels with the Wizard PCR Preps DNA purification system (Promega). The [α-32P]dCTP-labeled DNA molecules used as gene-specific probes were prepared with the Megaprime DNA labeling systems kit (Amersham Life Science). DNA sequences were determined by MWG Biotech AG or with the ABI 310 genetic analyzer at the Institute of Biology, National Center for Scientific Research, Demokritos.

agtA deletion.

Most of the agtA ORF sequence (an 1,848-bp region corresponding to protein residues 45 to 567) was replaced in a wA3 riboB2 pyroA4 pyrG89 biA1 strain with the riboB gene after a double-crossover event by the double-joint PCR gene replacement method (78). The primers used are listed in Table 2. In the deletion cassette, the sequence corresponding to the middle fragment of the double-joint PCR tripartite construction contains the riboB gene (replacing the agtA ORF) of A. nidulans amplified from plasmid pPL5 with primers DELA and DELB. The sequences corresponding to the fragments of 4,958 bp upstream and 4,760 bp downstream of the deletion were amplified from genomic DNA of a wild-type strain (pabaA1) with primer pairs DEL1-DEL3 and F2-R1, respectively. The whole deletion cassette used to transform a pyrG89 biA1 wA3 pyroA4 riboB2 strain was amplified with primers DEL2 and R2. Selection of transformants was carried out on NH4+-containing medium lacking riboflavin. agtA deletion and replacement by the riboB gene were monitored by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). Genomic DNAs of the recipient and transformant strains were digested with BamHI (an enzyme which has no recognition sites within the agtA or riboB gene) and hybridized with the purified ∼1.65-kb NotI-NotI fragment from plasmid pAB1 as an agtA probe and a riboB-specific probe, a fragment amplified by PCR from plasmid pPL5 with primers riboU (5′ CGTACGTAGTGTAGATTCAGG 3′) and riboL (5′ GACTACTAGGTGGTGCTATC 3′).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′ → 3′)a |

|---|---|

| DEL1 | AATCCTCCGAATAGCGACTGC |

| DEL2 | CCTCAGCAACTCCTCATCTCG |

| DEL3 | ATGCGACAAAGCATCTCACC |

| DELA | TACTATGATTGGTGAGATGCTTTGTCGCATCGTACGTAGTGTAGATTCAGGCACATTGAAGCG |

| DELB | GACCCGTAAGCATGGACATGAGCTAAGCGGAAAACTGCCATGACTACTAGGTGGTGCTATC |

| R1 | CGAATGGACGTGGTTGAAAGG |

| R2 | CGCTTGGCTTTCTCGTTGC |

| F2 | TGCTTAGCTCATGTCCATGC |

| AgtGFP1 | ATTGGGTTATACGTACGTCGCCAATGATTC |

| AgtGFP2 | GAACAGCCACGAGACAAAAGTCTTGTAGAA |

| AgtGFP3 | TTCTACAAGACTTTTGTCTCGTGGCTGTTCGGAGCTGGTGCAGGCGCTGGAGCC |

| AgtGFP4 | TGTGTAAGACAAGACAAAACCGGGACAAGAGTCTGAGAGGAGGCACTGATGCG |

| AgtGFP5 | ACGTTTATACTTGGGATTCCGACCGTCTTT |

| AgtGFP6 | GTACAATTTGATGACTAGGTATGGATCATCT |

| riboU | CGTACGTAGTGTAGATTCAGG |

| riboL | GACTACTAGGTGGTGCTATC |

| 14046R1 | TGGTGCATTGTCGTCTCCCTAACC |

| 14046R2 | CTGCTCAGCTGGATCTCCCTCC |

| G1 | TGGTTTCACTGGTTATGC |

| G2 | CCTTTGGTTCCGATGTGG |

| AgtAF | GAGGCGTCATGGGTGTCGAGAA |

| AgtAR | GACAAGACTAGAACAGCCACGAG |

Underlining in the AgtAF and AgtAR sequences indicates the translation start and stop codons, respectively.

Construction of agtA in-locus fusions.

We used the three-way PCR-based 3′ tagging protocol (77) to construct the C-terminal translational fusion cassettes agtA-gfp and agtA-HA (21, 39, 75). Three different PCR fragments were amplified to construct each of these cassettes. The primers used are listed in Table 2. In both cases, the fragments corresponding to the regions upstream and downstream of the ORF fusions were amplified with primer pairs AgtGFP1-AgtGFP2 and AgtGFP5-AgtGFP6, respectively, by using wild-type genomic DNA as the template. The central fragment of each cassette contains, besides the sequence corresponding to the tag (GFP or HA), the selection marker gene pyrG of A. fumigatus (73), which complements the pyrG89 mutation of A. nidulans. This central region was amplified from plasmids pl1503 (HA fusion, kindly provided by E. Espeso) and pl1439 (GFP fusion) with primers AgtGFP3 and AgtGFP4. In both plasmids, upstream of the sequence that encodes the tag, there is a hinge region that encodes 10 amino acids (five Gly-Ala repeats) in frame with the 5′ end of the tag ORF. The whole fusion cassettes, which were used to transform the MAD1425 strain, were amplified with primers AgtGFP1 and AgtGFP6. Selection of transformants was carried out on CM in the absence of uracil and uridine. The in-locus replacement of agtA with agtA-sgfp F0 and agtA-HA was confirmed by Southern blot analysis by cutting genomic DNA with EcoRI and hybridizing it with a probe corresponding to a PCR product of the agtA ORF, which was amplified with the primer pair AgtGFP1-AgtGFP2 (Table 2). All of the transformants checked by Southern blot analysis contained single-copy integrations in the agtA locus. These strains were outcrossed to be placed in an nkuA+ background. They all showed wild-type growth on aspartate and glutamate as nitrogen sources.

RNA manipulations.

Total RNA extraction from A. nidulans was carried out with the RNAPLUS (Q-BIOgene) or TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was separated on glyoxal agarose gels as described by Sambrook and Russell (54). The hybridization technique used was described by Gilstring et al. (19). To monitor RNA loading, the radish 18S rRNA gene was used as the probe (14). This corresponds to a 1.1-kb EcoRI-EcoRI fragment purified from plasmid pRG3. Steady-state agtA mRNA levels were monitored by hybridization with a probe corresponding to the purified ∼1.65-kb NotI-NotI fragment from plasmid pAB1. Quantification of Northern blot assays was carried out with a 400A PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences Data). Data were analyzed with Aida Image Analyzer v.422 (Raytest).

cDNA synthesis to determine the stop codon of the agtA ORF, as well as the polyadenylation site, was performed with the 5′/3′-RACE kit (Roche Diagnostic, Indianapolis, IN) and oligo(dT) primers in combination with 14046R1 (5′ TGGTGCATTGTCGTCTCCCTAACC 3′) and 14046R2 (5′ CTGCTCAGCTGGATCTCCCTCC 3′), which is positioned downstream of 14046R1. The PCR product obtained was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and sequenced.

cDNA synthesis to determine the start codon of the agtA ORF and the presence of introns was performed by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from germinating conidiospores of a wild-type strain (pabaA1) grown in the presence of glutamate as the sole nitrogen source at 25°C for 10 h. The RNA used as the template in an RT-PCR was further purified according to the RNeasy Mini protocol for RNA cleanup in the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). To avoid contamination with genomic DNA, ∼10 μg RNA was treated and cleaned with the TURBO DNA-free kit (Ambion). The absence of DNA contamination was verified by conventional PCR (approximately 45 cycles) by using as the template at least 2 μg of RNA. About 1 μg of RNA was used for RT with the SuperScript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions with both random hexamer primers and oligo(dT). The final step of PCR amplification from the total cDNA mixture was performed with forward and reverse primers that contain the translation start and stop codons, respectively, i.e., AgtAF (5′ GAGGCGTCATGGGTGTCGAGAA 3′ [the translation start codon is underlined]) and AgtAR (5′ GACAAGACTAGAACAGCCACGAG 3′ [the translation stop codon is underlined]). The final product was sequenced with the ABI 310 genetic analyzer at the Institute of Biology, National Center for Scientific Research, Demokritos.

Western blot analysis of tagged AgtA.

Extraction of membrane proteins from A. nidulans mycelia was carried out according to Emr and Rieder (16). To monitor de novo synthesized AgtA-HA molecules in the presence of glutamate, mycelia were grown for 15 h at 30°C in MM with ammonium as the nitrogen source and then transferred to MM containing glutamate as the sole nitrogen source for different time intervals (1, 2, and 3 h). To monitor the effect of ammonium on de novo synthesized AgtA-HA levels, mycelia were grown for 15 h at 30°C in MM with ammonium as the nitrogen source and then transferred to MM containing glutamate, and after 2 h of incubation, ammonium was added and the cultures were left for different time intervals (10, 20, 30, 40, 60, and 90 min). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis were carried out according to references 5 and 9. The first antibody used to detect AgtA-HA was anti-HA high affinity (rat; catalog no. 1 867 423/431; Roche). The secondary antibody was a goat anti-rat immunoglobulin M (IgM) plus IgG (heavy and light chain specific)-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (catalog no. 3010-05; Southern Biotech).

Substrate transport assays.

l-[2,3-3H]aspartic acid uptake assays were performed with germinating conidia of strains AA1 (AgtA+) and CS1945 (AgtAΔ) grown in MM with glutamate as the sole nitrogen source (pH 6.5) at 37°C as previously described (61, 62, 63), harvested, and resuspended in MM with urea as the sole nitrogen source. Standard assays for the determination of initial uptake rates were performed with A. nidulans in MM (pH 6.8) with 0.5 μCi of l-[2,3-3H]aspartic acid per assay (1 mCi/ml; specific activity, 15 to 50 Ci · mmol−1; catalog no. TRK574; Amersham Biosciences, Amersham, United Kingdom). After preincubation of 90 μl of germinating conidia in MM with urea as the sole nitrogen source for 10 min at 37°C, a 10-μl mixture of labeled and unlabeled aspartate (the final concentration of unlabeled aspartate in these samples varied between 5 and 500 μM for the Michaelis constant [Km] and maximal velocity [Vmax] determination experiments) was added and the samples were incubated at 37°C for 2 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 ml of MM containing 3 mM aspartic acid, the samples were placed on ice and washed three times with ice-cold MM, and radioactivity was measured in sediment by liquid scintillation counting (Tri-Carb 210 TR liquid scintillation analyzer; Packard). Initial uptake rates were expressed in picomoles of substrate incorporated per minute per 108 viable conidia. The reported results for each type of uptake assay represent the mean values of three independent experiments. The apparent Km and Vmax values for l-[3H]aspartic acid were determined from double-reciprocal plots of the initial uptake rates against the substrate concentration.

The Ki value of AgtA for glutamate was calculated as described above, except for the following modifications. Ten microliters of a mixture of labeled aspartic acid (0.5 μCi/assay) and unlabeled glutamate (so that the final concentration of glutamate varied between 50 and 500 μM) was added to each 90-μl assay reaction mixture used. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 ml of MM containing 3 mM glutamate. Samples were washed three times with ice-cold MM and placed on ice. Radioactivity measurements were carried out as previously described (17). The Ki value was calculated by using the values obtained from two independent experiments.

Competition experiments were performed under the same experimental conditions described above for uptake experiments, except for the following modifications. Ten microliters of a mixture of labeled aspartic acid (0.5 μCi), 800 μM unlabeled aspartate, and 10 mM inhibitor (alanine, aspartate, glutamate, or glutamine) was added to each 90-μl assay reaction mixture used (in order to have final concentrations of 80 μM aspartate and 1 mM inhibitor). After 2 min at 37°C, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 ml MM containing 3 mM aspartate. Radioactivity measurements were done as previously described. The reported results for each type of uptake assay represent the mean values of three independent experiments.

Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM).

Ten microliters of a suspension of 5 × 105 conidia/ml was inoculated onto sterile coverslips embedded in appropriate liquid culture medium, incubated for a total of 16 h at 25°C, and observed by CSLM as previously described (61, 62). Ammonium l(+)-tartrate was added to a final concentration of 10 mM at 2 h or 30 min before observation, as indicated in the figure legends, while cycloheximide was added to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml at 30 min before observation. Labeling of A. nidulans vacuoles was carried out with CMAC (7-amino-4-chloromethyl coumarin; Molecular Probes) dye at 5 mg/ml (43) as described in reference 61. LSCM was carried out on a Bio-Rad MRC 1024 confocal system (Laser Sharp Version 3.2 Bio-Rad software, zoom ×2, excitation at 488 nm/blue, samples at laser power 30%, Kalman filter N = 5 to 6, 0.3-μm cut, iris at 7 to 8, krypton/argon laser, Nikon Diaphot 300 microscope, 60× [oil immersion] lens, emission filter 522/DF35; lens reference, Plan Apo 60/1.40 oil DM, Nikon Japan 160175, 60 DM/Ph4, 160/0.17).

Bioinformatic tools and databases.

The databases consulted were the Aspergillus Comparative Database (Broad Institute) at http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/aspergillus_terreus/MultiHome.html, the A. nidulans Linkage Map (compiled by J. A. Clutterbuck) at http://www.gla.ac.uk/acad/ibls/molgen/aspergillus/index.html, the Saccharomyces Genome Database at www.yeastgenome, and the Transport Classification Database (compiled by Milton H. Saier, Jr.) at www.tcdb.org.

Amino acid transporter alignments were carried out with ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html), Muscle (http://phylogenomics.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/muscle/input_muscle.py), and T-Coffee (http://tcoffee.vital-it.ch/cgi-bin/Tcoffee/tcoffee_cgi/index.cgi). Phylogenetic analyses were carried out with and without curation with G-blocks (http://www.phylogeny.fr/version2_cgi/advanced.cgi) with PhyML (http://atgc.lirmm.fr/phyml/), altR-PhyML (http://www.phylogeny.fr/version2_cgi/advanced.cgi), and ProtDist or ProtPars (http://mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/MobylePortal/portal.py) with the Muscle and the Coffee alignments and visualized with Phylodendrum (http://iubio.bio.indiana.edu/treeapp) or Drawtree (http://mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/MobylePortal/portal.py). Transporter topologies were predicted with five different softwares, TMHMM v2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/), TMpred (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPREDform.html), TopPred (http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/seqanal/interfaces/toppred.html), HMMTOP (http://www.enzim.hu/hmmtop/), and SOSUI (http://sosui.proteome.bio.tuat.ac.jp/sosuiframe0E.html). Putative posttranslational modification sites were searched at http://www.expasy.ch/tools/.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete sequence of the agtA cDNA clone obtained by RT-PCR has been deposited in GenBank under accession number EU604104.

RESULTS

Identification and characterization of agtA, which encodes the dicarboxylic amino acid transporter of A. nidulans.

In silico analysis of the A. nidulans genome database (http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/fungi/) by using as probes the sequences of two characterized dicarboxylic amino acid transporters, Dip5p of S. cerevisiae (47) and PcDip5 of P. chrysogenum (68), revealed an ORF of 1,972 bp in supercontig 1.104 (AN6118.3 gene) coding for a polypeptide chain of 567 amino acid residues and showing 44 and 57% amino acid identity with Dip5p and PcDIP5, respectively.

Strains mutant for the AN6118.3 ORF (see Materials and Methods) do not utilize aspartate and show markedly impaired utilization of glutamate as the sole nitrogen source. The residual growth seen on aspartate in Fig. 1 is equivalent to the growth in the absence of any nitrogen source added to the medium (results not shown). The deletion does not affect growth on MM supplemented with urea, ammonium, uric acid, or any of the following amino acids: glutamine, asparagine, proline, arginine, ornithine, glycine, alanine, leucine, isoleucine serine, threonine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan, β-alanine, and γ-aminobutyric acid, all of which can be used by A. nidulans as sole sources of nitrogen (Fig. 1). These results strongly suggest that the ORF contained in AN6118.3 encodes a specific dicarboxylic amino acid transporter. The gene corresponding to AN6118.3 was called agtA (for aspartate glutamate transporter A).

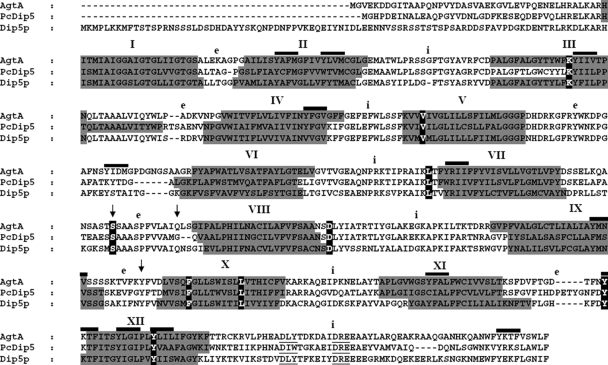

The presence and position of the three putative introns predicted in the AN6118.3 gene model were confirmed by sequencing the complete agtA cDNA clone obtained by RT-PCR. A 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends experiment and the sequence of the cDNA clone confirmed the termination codon at position +1970 with respect to the adenine base (+1) of the ATG initiation codon and a polyadenylation site 118 bp downstream of the stop codon. agtA encodes a protein of 567 amino acids belonging to the YAT family that shows >30% identity with other physiologically characterized YAT members (25; data not shown). Figure 2 shows the alignment of the three characterized dicarboxylic amino acid transporters, together with their putative transmembrane domain organization. AgtA, Pcdip5, and Dip5p present characteristically conserved residues (in black in Fig. 2) which are not shared with any other YAT transporter.

FIG. 2.

ClustalW2 alignment of the three specific dicarboxylic amino acid transporters of the YAT family: AgtA (A. nidulans), Pcdip5 (P. chrysogenum), and Dip5p (S. cerevisiae). Marked in gray are the putative transmembrane segments of each transporter according to Toppred (http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/seqanal/interfaces/toppred.html). The amino acid residues specific only to the dicarboxylic amino acid transporters are shaded in black. Ser318, Gln329, and Tyr413 are indicated by arrows (see Discussion). The YXXΦ motifs (Y motifs [see Discussion]) of AgtA are overlaid by a thick line. i, intracytoplasmic loops; e, extracytoplasmic loops.

Kinetic characterization of the AgtA transporter.

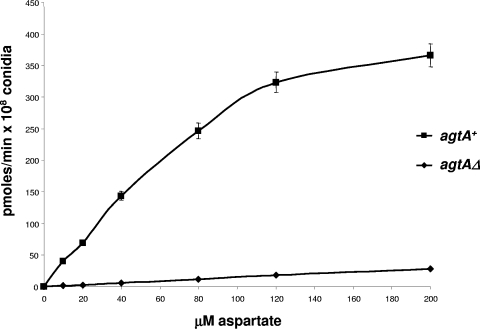

Figure 3 shows aspartate uptake rates of agtA+ and agtAΔ germlings as a function of aspartate concentration. The marginal uptake of aspartate seen with the deletion mutant, in conjunction with growth tests described above, demonstrates that AgtA is the major, possibly the only, transporter able to incorporate aspartate. Analysis of the results obtained from three independent experiments by Lineweaver-Burk plots (data not shown) established a Km of 70 ± 5 μM and a Vmax (under the experimental conditions tested) of 415 ± 20 pmol min−1 108 viable conidiospores−1.

FIG. 3.

Kinetics of aspartate transport in wild-type (agtA+) and agtAΔ mutant strains. Each point is the average of three independent measurements. Aspartate uptake rates are expressed in picomoles per minute per 108 viable conidiospores. Analysis of these results by a Lineweaver-Burk plot (not shown) established the existence of a high-affinity aspartate transporter with a Km of 70 μM only in the wild-type strain.

Experiments examining competition for the AgtA-mediated aspartate uptake by a 12.5-fold excess of unlabeled aspartate, glutamate, alanine, or glutamine showed that uptake of l-[2,3-3H]aspartic acid was markedly inhibited by unlabeled aspartate (∼60%) and unlabeled glutamate (∼63%) but not by alanine or glutamine, confirming that AgtA is specific for aspartate and glutamate (data not shown). By saturation kinetic analyses in the presence of unlabeled glutamate at concentrations of 50 to 500 μM (see Materials and Methods), we additionally determined that the Ki of AgtA for glutamate competition for aspartate uptake is 155 ± 13 μM, which confirms that AgtA mediates glutamate uptake.

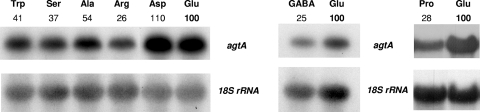

agtA is expressed in the presence of amino acids as sole nitrogen sources.

As the ability of A. nidulans to incorporate the dicarboxylic amino acids is dependent on the nitrogen and carbon sources present in the growth medium (24, 42, 51, 52), we analyzed the transcriptional regulation of agtA in response to nitrogen source availability. Preliminary experiments (and see below) failed to show detectable expression of agtA in mycelia grown on nitrogen sources usually considered nonrepressive such a urea or uric acid. Figure 4 shows that agtA is expressed when aspartate or glutamate, both substrates of AgtA, is used as the sole nitrogen source. In the presence of other l-amino acids such as tryptophan, serine, alanine, arginine, proline, and γ-aminobutyric acid, whose utilization is not affected by an agtAΔ null allele strain, agtA is also expressed, although at levels lower than those observed on aspartate or glutamate (see Discussion).

FIG. 4.

Northern blot analysis of agtA expression in mycelia of a wild-type (pabaA1) strain in the presence of different amino acids (Asp, aspartate; Glu, glutamate; Trp, tryptophan; Ser, serine; Ala, alanine; Arg, arginine; Pro, proline; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid) as sole nitrogen sources. The three panels represent independent experiments. The growth conditions and probes used are described in Materials and Methods. Quantification of the transcript (above the Northern blot) was corrected for the loading with the 18S rRNA signal and expressed in 100% of the value obtained for glutamate in order to compare the results of different experiments.

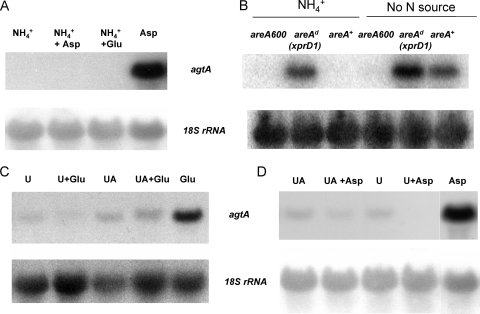

agtA expression requires the GATA factor AreA and is extremely sensitive to nitrogen metabolite repression.

No transcription of agtA can be detected in the presence of ammonium, independently of whether aspartate or glutamate, the substrates of AgtA, is present in the culture medium. Figure 5A shows that when the mycelium is nitrogen starved, agtA is strongly expressed and, in addition, that the GATA factor AreA is essential for agtA expression. The latter was determined under conditions of nitrogen starvation, where the possible exclusion (which would presumably occur in an areA mutant) of an external metabolite that could act as an inducer of agtA expression becomes irrelevant. At variance with what is seen in the wild type, in an areA null mutant (areA600), nitrogen starvation conditions do not result in detectable agtA expression (Fig. 5B). In agreement with a crucial role for AreA in agtA regulation, very strong expression is seen in an extreme derepressed allele of areA (called xprD1; 10, 44) both in the presence of ammonium and under conditions of starvation. Unexpectedly, we found no or very weak expression on urea or uric acid, which are generally regarded as nonrepressive nitrogen sources, irrespectively of the presence of aspartate or glutamate (Fig. 5C and D).

FIG. 5.

Sensitivity of agtA expression to nitrogen metabolite repression. (A) Northern blot analysis of agtA expression by wild-type strain (pabaA1) mycelia after 7 h of growth in the presence of ammonium as a sole nitrogen source, followed by 2 h of additional incubation in the sole presence of ammonium (first lane) or in the simultaneous presence of ammonium and aspartate (second lane) or ammonium and glutamate (third lane) and, as a control, aspartate alone (fourth lane). (B) Northern blot analysis of agtA expression in mycelia of strains carrying different areA alleles grown for 7 h on ammonium and subsequently shifted to medium either containing ammonium or without any nitrogen source for an additional 2 h. areA600 is a null areA mutant, areAd (xprD1) is a derepressed areA mutant, and areA+ is a wild-type (pabaA1) strain. Strains, growth conditions, and probes are described in Materials and Methods. (C) Northern blot analyses of agtA expression in mycelia of a wild-type strain (pabaA1) grown in urea (U) or uric acid (UA) in the presence of glutamate (Glu) or, as a control, in glutamate only. (D) Northern blot analyses of agtA expression in mycelia of a wild-type strain (pabaA1) grown in urea (U) or uric acid (UA) in the presence of aspartate (Asp) or, as a control, in aspartate only.

This experiment leaves open the question of whether aspartate and/or glutamate are agtA-specific inducers. Figure 6 shows that consistently high expression of agtA is obtained in an xprD1 mutant, irrespectively of the nitrogen source, even in the absence of any amino acid (see the urea and uric acid tracks), and including nitrogen sources shown to be generally strongly repressing (ammonium and glutamine). This confirms that nitrogen metabolite repression is the principal mechanism that regulates agtA expression. It is noteworthy that expression in the presence of proline does not seem to be affected by the xprD1 mutation.

FIG. 6.

Effect of an areA derepressed mutation (xprD1) on the expression of agtA. The levels of expression of agtA in an areA+ strain (+ lanes) are compared to those found in a strain carrying an extremely derepressed areA mutation (xprD1; d lanes) on different nitrogen sources. The strains, growth conditions, and probes used are described in Materials and Methods. The nitrogen source used is indicated above each pair of lanes. Abbreviations: Gln, glutamine; UA, uric acid; Pro, proline; Glu, glutamate. Quantification of the transcript (above the Northern blot) was corrected for the loading with the 18S rRNA signal and expressed as a percentage of the value obtained for glutamate, which was set at 100%. ND, nondetectable signal.

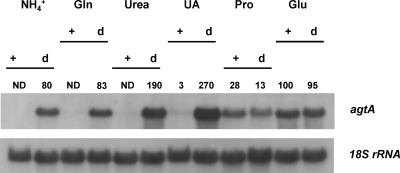

Expression of agtA following germination.

A number of transporter genes, including the A. nidulans proline-specific transporter gene prnB (57), are expressed during conidial isotropic growth. This expression, which is independent from the regulatory circuits operating in mycelia (1, 64), lasts for about 4 h after conidial germination in liquid MM at 37°C (1).

Figure 7 shows that agtA is transcribed at relatively high levels at the 2-h time point after induction of germination (corresponding to the isotropic growth phase), where transcript levels are very similar on glutamate and urea, but transcription is progressively switched off when urea is the nitrogen source, attaining relatively low levels at the 8-h time point, where a majority of germinating spores have established polarity and given rise to germlings. In the presence of ammonium as the nitrogen source, agtA mRNA is barely detectable during the first 4 h of germination but absent at later times. These results indicate that agtA expression is more sensitive to nitrogen metabolite repression after polarity establishment than during the isotropic growth phase.

FIG. 7.

agtA expression during development in the presence of different nitrogen sources. Shown are steady-state agtA mRNA levels in germinating conidia (2 and 4 h) and young (6 and 8 h) mycelia of a wild-type strain (pabaA1) at 37°C in the presence of glutamate, urea, or ammonium as the sole nitrogen source. The growth conditions and probes used are described in Materials and Methods.

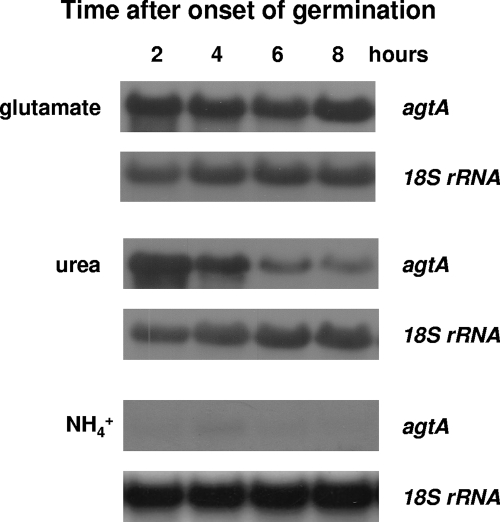

Subcellular localization of the AgtA transporter.

Strains carrying an agtA-gfp fusion showed wild-type growth on aspartate and glutamate as nitrogen sources (Fig. 1; see Materials and Methods for details). Epifluorescence (not shown) and confocal (Fig. 8A) microscopy revealed that in germlings cultured on glutamate as the only nitrogen source, AgtA-GFP localizes to the peripheral and septal plasma membrane and to the vacuolar lumen, as has been reported for other A. nidulans plasma membrane transporters (41, 61, 70).

FIG. 8.

ShrA and ammonium-dependent subcellular localization and degradation of AgtA. At the top are representative pictures from LSCM of shrA+ agtA::gfp (A) and shrAΔ agtA::gfp (B) strains expressing a functional chimeric AgtA-GFP fusion, grown at 25°C for 16 h on MM in the presence of 10 mM glutamate as the sole nitrogen source. Bars, 10 μm. (C) Representative pictures from LSCM of an shrA+ agtA::gfp strain grown as described above, followed by the addition of 10 mM ammonium tartrate for the last 30 min (left) compared with CMAC staining (right) as described in reference 61. Bars, 10 μm. (D) Western blot analysis of AgtA-HA expression under different growth conditions showing the kinetics of AgtA-HA appearance in mycelia grown on ammonium for 15 h (time zero) after a shift to glutamate for 1, 2, and 3 h, respectively. Time in minutes is indicated at the top. (E) Kinetics of AgtA-HA ammonium-elicited degradation. Mycelia pregrown on ammonium for 15 h as above were transferred to glutamate for 2 h (derepressed conditions, time zero), transferred again to NH4+, and analyzed after 10 to 90 min of incubation. Time of incubation in minutes is indicated at the top. For further details on growth conditions, see Materials and Methods.

ShrA, the A. nidulans Shr3p orthologue (see introduction), is required for full growth on aspartate or glutamate as the sole nitrogen source and for full aspartate uptake activity (30; see also Fig. 1), suggesting that AgtA might be one of its substrates. We thus investigated the localization of AgtA-GFP in an shrAΔ mutant strain. Figure 8B shows that shrAΔ results in predominant vacuolar, rather than plasma membrane, localization of AgtA-GFP.

Ammonium promotes the endocytic internalization and degradation of AgtA.

Figure 8C shows that shifting cells cultured on glutamate to medium containing ammonium for 30 min results in a drastic increase in fluorescence in the vacuolar lumen, apparently at the expense of plasma membrane AgtA-GFP. While this vacuolar localization might result from transcriptional repression coupled with a nonregulated cycling mechanism of membrane proteins, the relatively high speed at which AgtA disappears from the plasma membrane strongly suggested that ammonium promotes the endocytic internalization of AgtA and its subsequent sorting into the multivesicular body pathway (ammonium inactivation; 41, 71) in concert with but independently of transcriptional repression. This is shown formally below.

The above experiments strongly indicate that AgtA-GFP undergoes ammonium-dependent internalization and reaches the vacuolar lumen after being sorted into the multivesicular body pathway. GFP is recalcitrant to vacuolar proteolysis (which explains why the vacuolar lumen displays a strong fluorescent signal). To investigate the effect of ammonium on AgtA degradation, we constructed a strain carrying an in-locus agtA variant that encodes a C-terminally (HA)3-tagged version of the permease (see Materials and Methods). The steady-state levels of AgtA-HA3 were analyzed by Western blot analysis of crude membrane fractions. A protein with the expected mobility of AgtA-HA3 (molecular mass, ∼67 kDa) was detected in cells precultured on synthetic medium containing ammonia as the nitrogen source, shifted to glutamate medium, and incubated for a further 1 h (Fig. 8D). Steady-state levels of AgtA-HA3 increased with the time of incubation in glutamate-containing medium, reaching a maximum after a 3-h incubation period. Western blot analyses additionally revealed the presence of a faster-migrating polypeptide whose levels relative to that of the slower AgtA-HA3 band varied among different experiments. Treatment with lambda protein phosphatase did not change the AgtA migration pattern, which suggests that the different AgtA bands observed do not involve different phosphorylation states (L. Harispe, C. Scazzocchio, and M. A. Peñalva, unpublished results). Putative N-glycosylation and O-glycosylation sites can be detected in silico, and thus the possibility cannot be excluded that differential glycosylation accounts for these differently migrating bands. An alternative translational initiation is extremely unlikely, as the first possible alternative methionine lies within the first transmembrane segment (Fig. 2). The faster-running band could probably result from N-terminal degradation.

To monitor the effect of ammonium on the de novo synthesized AgtA-HA3, mycelia were grown for 15 h at 30°C in ammonium-containing synthetic CM and transferred to glutamate. After a 2-h incubation on glutamate, which led to the detection of relatively high AgtA-HA3 levels (Fig. 8D), ammonium was added to the culture and the steady-state levels of AgtA-HA3 were analyzed by Western blotting at different time points. Figure 8D demonstrates that AgtA-HA3 levels showed a rapid, sharp decline upon ammonia addition, such that the transporter was barely detectable after 30 min of incubation in the presence of ammonia. These results, in conjunction with the above confocal microscopy observations, strongly indicate that ammonium promotes the endocytic internalization and subsequent sorting into the multivesicular body pathway of plasma membrane-localized AgtA, thus leading to the vacuolar degradation of the transporter.

AgtA endocytic internalization is not a consequence of ammonium repression.

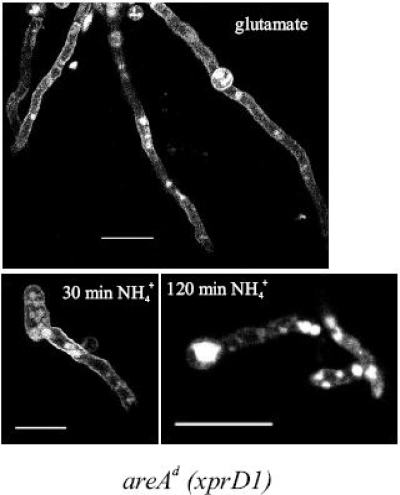

To further support the contention that the reduction in the plasma membrane level of AgtA is not an indirect, passive, result of transcriptional repression but involves a posttranscriptional downregulation mechanism that responds specifically to ammonium, we used three different approaches. Firstly, we investigated whether other repressing nitrogen sources such as urea, uric acid, and glutamine mimic the effect of ammonium. Glutamine results in AgtA delivery to the vacuole, while urea or uric acid does not affect its membrane localization (not shown). Secondly (Fig. 9), we investigated the endocytic downregulation of AgtA in an xprD1 strain insensitive to ammonium repression of agtA transcription (see above). High expression of AgtA, which mainly localizes to the plasma membrane, can be seen in cells grown on glutamate. In cells subsequently shifted to ammonia for 30 min, AgtA localizes to the vacuoles but, in contrast to the wild type (Fig. 8), relatively high levels are still present in the plasma membrane. Only at 2 h after cells were shifted to ammonium did AgtA localize almost exclusively to the vacuole. This difference in internalization kinetics between a wild-type and a derepressed strain possibly reflects the fact that agtA is permanently transcribed in the latter, whether ammonium is present or not.

FIG. 9.

AgtA internalization occurs in an areA-derepressed strain. Shown is the subcellular localization of AgtA protein in young hyphae of an ammonium-derepressed strain (xprD1) of A. nidulans in the presence of ammonium. Representative pictures from LSCM show conidiospores of a wild-type strain (pabaA1) expressing functional AgtA-GFP molecules, grown at 25°C for 16 h on MM in the presence of 10 mM glutamate as the sole nitrogen source with the addition of 10 mM ammonium tartrate (NH4+) for the last 30 or 120 min of growth, respectively. Bars, 10 μm.

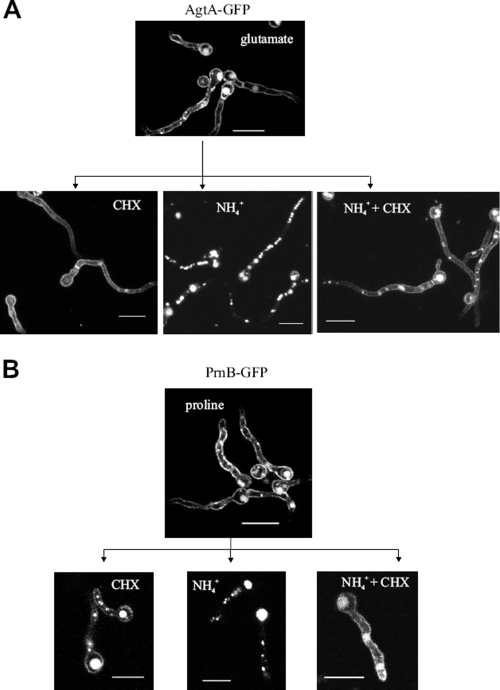

In a third, independent approach, we used the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (6, 13, 55). The drug by itself does not result in vacuolar localization of AgtA-GFP (Fig. 10A). Moreover, it impedes the ammonium-dependent vacuolar localization of AgtA-GFP, leading to persistence of the permease in the plasma membrane. This experiment demonstrates that AgtA delivery from the plasma membrane to the vacuole requires protein synthesis (Fig. 10A).

FIG. 10.

Protein synthesis is necessary for ammonium-dependent AgtA and PrnB internalization. Shown is the subcellular localization of AgtA and PrnB proteins in young hyphae of A. nidulans strains under conditions that inhibit protein synthesis. Representative pictures from LSCM show conidiospores of a wild-type strain (pabaA1) that expresses functional AgtA-GFP (A) or PrnB-GFP (B) molecules grown at 25°C for 16 h on MM in the presence of 10 mM glutamate as the sole nitrogen source, followed by the addition of 10 mM ammonium tartrate (NH+4[r]), 0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide (CHX), or both (NH+4[r] + CHX) for the last 30 min of growth (A), or in the presence of 10 mM proline as the sole nitrogen source, followed by the addition of 10 mM ammonium tartrate (NH+4[r]), 0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide (CHX), or both (NH+4[r] + CHX) for the last 30 min of growth (B). Bars, 10 μm.

The activity of the proline transporter PrnB is also sensitive to ammonium downregulation (20, 63). We thus investigated whether this permease responds to ammonium analogously to AgtA. Figure 10B shows that the regulation of the subcellular localization of PrnB follows the same pattern as AgtA, i.e., vacuolar localization in the presence of ammonium and plasma membrane localization in the presence of the inhibitor. These results suggest that we are dealing with a mechanism of ammonium-promoted endocytic internalization general for A. nidulans amino acid transporters and that such internalization necessitates protein synthesis.

DISCUSSION

There is one specific dicarboxylic amino acid transporter in A. nidulans.

AgtA is the only major transporter involved in the uptake of dicarboxylic amino acids. Our kinetic data are highly consistent with those previously published (42, 51, 52). Our data are consistent with the existence of only one uptake system for aspartate. Growth tests showed that strains carrying agtA null mutations maintain some growth on glutamate as a sole nitrogen source. These tests were carried out with 10 mM glutamate, a concentration markedly above the Km of AgtA. Thus, in all likelihood, another low-affinity transporter(s) can also take up glutamate. One candidate could be a general amino acid permease. The general amino acid permease of P. chrysogenum, a fungus closely related to A. nidulans, shows considerably better uptake of glutamate than of aspartate when overexpressed in S. cerevisiae (68).

Phylogenetic analysis of physiologically characterized transporters of the YAT family (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) shows clear clustering of the three known dicarboxylic amino acid transporters. As also the two characterized proline transporters cluster together, transporter specificity in the YAT family probably diverged before the separation of the Saccharomycotina (S. cerevisiae) from the Pezizomycotina (Aspergillus and Penicillium). In contrast, the transporters characterized as general amino acid permeases show a scattered distribution. This may indicate that “general amino acid permease” is simply a denomination given to transporters with broad but not necessarily identical substrate specificity and/or that, within the YAT family, convergent evolution toward a general transporter has occurred a number of times. We consistently found in trees constructed with different algorithms (see Materials and Methods) that the closest relative of the dicarboxylic amino acid transporters is the amino acid sensor system component Ssy1p (15, 18, 27).

Residues that are uniquely conserved among the dicarboxylic acid transporters are highlighted in Fig. 2. Among these, Ser318 corresponds to Tyr356 of Can1p, which was previously shown to be involved in substrate recognition specificity (48). Gln329 in AgtA is conserved in Dip5p (and, with a slightly different positioning of the relevant gap in the alignment, also in PcDip5) and corresponds to Glu367 in Can1p. Glu367 was proposed to confer Can1p specificity for basic amino acids. Tyr413, which is conserved among the three dicarboxylic amino acid transporters, corresponds to Trp451, another residue involved in the substrate specificity of Can1p (48). Thus, the polar Ser318 and Gln329 residues and the aromatic Tyr413 residue are good candidates to confer the substrate specificity of AgtA and its orthologues.

Sensitivity of agtA transcription to nitrogen metabolite repression.

Ammonium, a strongly repressing nitrogen source, inhibits uptake of dicarboxylic amino acids (42, 52), suggesting that the expression of the glutamate transporter is AreA dependent (30, 42). Our data show that in the presence of a repressing carbon source (glucose), agtA transcription is extremely sensitive to nitrogen metabolite repression and strictly necessitates the AreA transcription factor. We have not investigated whether this sensitivity to ammonium is dependent on the carbon source. The fact that many different amino acids or the absence of a nitrogen source permits agtA transcription suggests that specific induction is not a prerequisite for agtA expression. Urea is considered a noninducing, nonrepressing “neutral” nitrogen source for a number of genes involved in nitrogen source utilization (4, 7, 37, and references therein). However, our data indicate that this is not the case for agtA. Even more surprising is the fact that uric acid, a less favorable nitrogen source than urea, is also repressing. This implies that even very low intracellular concentrations of the nitrogen-repressing metabolite (which may be glutamine [36]) are able to repress the transcription of agtA. Repression by urea, uric acid, ammonium, and glutamine is relieved by the xprD1 allele, the strongest derepressed allele of areA available (36, 44).

The higher levels of agtA mRNA seen on glutamate and aspartate compared to other amino acids can be explained simply without the involvement of a specific induction mechanism. When strains are grown on glutamate or aspartate, the intracellular concentration of glutamine (or whatever the actual repressing metabolite may be) necessarily depends on the uptake of the sole nitrogen sources (glutamate and/or aspartate) and thus on agtA expression, which is, in turn, repressed by the repressing metabolite. Thus, in the presence of aspartate or glutamate (but not of amino acids independently taken up by other transporters), a negative feedback loop would minimize the intracellular concentration of the repressing metabolite, thus maximizing steady-state agtA mRNA levels. In an xprD1 background, where the negative feedback loop is absent, similar agtA transcript levels are seen in most of the nitrogen sources tested (including the most strongly repressing, such as ammonium and glutamine), which indicates that specific induction plays a very minor role, if any, in the regulation of agtA expression. The very high derepressed levels seen on uric acid and to lesser extent on urea, while not easily accounted for, also argue against specific induction by glutamate and/or aspartate. Proline, surprisingly, leads to intermediate levels of expression that are not increased by xprD1. We note that whereas utilization of urea and uric acid proceeds via ammonium (56), utilization of proline proceeds via glutamate (5).

AreA is a positively acting transcription factor whose function is negated by ammonium. The extreme sensitivity of agtA to nitrogen metabolite repression implies that the concentration of active AreA needed to elicit agtA promoter transcription may be higher than that required in promoters showing less sensitivity to nitrogen metabolite repression, such as those of the nitrate and purine utilization pathways. In these gene promoters, AreA acts synergistically with the pathway-specific transcription factors UaY (12 and references therein) and NirA (7 and references therein), respectively, and indeed a direct interaction has been demonstrated in vitro for NirA and AreA (37). If, as our data strongly indicate, agtA is not subject to specific induction, no synergic AreA interaction with a specific transcription factor could take place. In addition, AreA binds cooperatively to GATA sites that are separated by a few base pairs (46). The five canonical GATA sites (HGATAR [46]) that are present within the 600-bp region upstream of the ATG codon of agtA are widely separated (data not shown), which argues against the possibility of cooperative binding of AreA molecules. We speculate that the absence of pathway-specific induction, in combination with the unfavorable disposition of GATA sites on the promoter, may result in the necessity of a higher concentration of AreA in the nucleus to activate agtA transcription and thus in a higher sensitivity to nitrogen metabolite repression.

Posttranslational control of AgtA localization.

As expected from its role in the uptake of dicarboxylic amino acids, AgtA-GFP localizes to the plasma membrane in cells cultured on glutamate as the sole nitrogen source. However, a significant proportion is found in the lumen of the large basal vacuoles, indicating that AgtA-GFP is sorted into the multivesicular body pathway (the GFP moiety, attached to the C terminus of AgtA being recalcitrant to vacuolar proteolysis). ShrA is the orthologue of S. cerevisiae Shr3p, a protein that assists the folding of amino acid permeases and prevents precocious ER-associated degradation (28, 29). The relative proportion of AgtA-GFP localizing to the vacuolar lumen is increased in shrAΔ mutants, apparently at the expense of that in the plasma membrane, which strongly suggests that acquisition of the correct folding and/or exiting from the ER is a limiting step for its delivery to the plasma membrane.

Endocytic downregulation of AgtA by ammonium.

In addition to promoting nitrogen metabolite repression at the transcriptional level, ammonium promotes the delivery of plasma membrane AgtA to the vacuolar lumen, which correlates with its rapid, also ammonium-elicited, degradation. Several lines of evidence strongly support the notion that this phenomenology involves the sorting into the multivesicular body pathway of AgtA molecules that reach the endosomal system following their endocytic internalization. (i) A sharp and rapid increase in vacuolar fluorescence and a nearly complete loss of plasma membrane fluorescence are seen when AgtA-GFP cells are shifted to ammonium. (ii) Western blot analyses showed that in cells cultured on glutamate and subsequently shifted to ammonium, AgtA levels undergo a fast (within 10 min) and drastic decrease. (iii) The endocytic downregulation of AgtA is independent of transcriptional repression (as shown with a derepressed mutant). (iv) Cycloheximide, by itself, does not promote delivery of plasma membrane AgtA-GFP to the vacuole and moreover precludes the ammonium-induced internalization of AgtA-GFP (and of PrnB-GFP) from the plasma membrane, which confirms that AgtA internalization does not take place through a passive mechanism, subsequent to transcriptional repression. The endocytic downregulation by ammonia of the purine transporters UapC and UapA, respectively, involved in the uptake of xanthine and uric acid, is well established (41, 71). The unexpected finding that cycloheximide prevents the endocytic internalization of AgtA and PrnB indicates that this process requires protein synthesis. Analogous results have been obtained for the purine permease UapA (A. Pantazopoulou and G. Diallinas, personal communication). As established for S. cerevisiae plasma membrane transporters, the endocytic internalization and multivesicular body sorting of AgtA, PrnB, UapA, and UapC (23, 49, 50) in all likelihood involves their ubiquitination. How this process is triggered by ammonium is a matter for future investigation. The predictably cytosolic C-terminal domain of AgtA contains a consensus YXXΦ motif, where Φ is a hydrophobic amino acid. YXXΦ motifs interact with the μ subunit of AP-2 (adaptor complex 2), which mediates the sorting of endocytic cargo into clathrin-coated pits (see reference 58 for a review). In conclusion, AgtA is the only specific dicarboxylic amino acid transporter of A. nidulans. It is not subject to a specific induction system, but it is unusually sensitive to nitrogen metabolite repression. In addition, and in common with a number of transporters involved in the utilization of nitrogen sources, it is subject to endocytic downregulation. The transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms act concertedly to suppress dicarboxylic amino acid uptake in the presence of favored nitrogen sources such as ammonium and glutamine. The characterization of AgtA provides a useful system to study posttranslational regulation by preferred nitrogen sources and to investigate the role of factors controlling the intracellular trafficking of transporters of the YAT family.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Espeso for helpful discussion and J. Vagelatos for extensive critical advice concerning LSCM.

A. Apostolaki was supported by European Union contract EUROFUNG QLK3-CT1999-00729. L. Harispe was partially supported by the Direction des Rélations Internacionales (Université Paris-Sud) and by the Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional (Spain). Work in Orsay was supported by the above contract, the Université Paris-Sud, the CNRS, and the Institut Universitaire de France. Work in Madrid was supported by DGCYT grant BIO2005-0556 and Comunidad de Madrid grant S2006/SAL-0246 to M.A.P. Work in Athens was supported by NCSRD and a research grant from the Greek General Secretariat for Science and Technology (EPETII PENED 03 EΔ/158) to V.S.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 January 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amillis, S., G. Cecchetto, V. Sophianopoulou, M. Koukaki, C. Scazzocchio, and G. Diallinas. 2004. Transcription of purine transporter genes is activated during the isotropic growth phase of Aspergillus nidulans conidia. Mol. Microbiol. 52205-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andre, B. 1995. An overview of membrane transport proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 111575-1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apostolaki, A. 2003. Topogenèse des transporteurs d'acides aminés chez le champignon filamenteux Aspergillus nidulans. Ph.D. thesis. Université Paris-Sud, Paris, France.

- 4.Arst, H. N., Jr., and D. J. Cove. 1973. Nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 126111-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arst, H. N., Jr., S. A. Jones, and C. R. Bailey. 1981. A method for the selection of deletion mutations in the l-proline catabolism gene cluster of Aspergillus nidulans. Genet. Res. 38171-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arst, H. N., and C. Scazzochio. 1972. Control of nucleic acid synthesis in Aspergillus nidulans. Biochem. J. 12718P. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1178632&blobtype=pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernreiter, A., A. Ramon, J. Fernández-Martínez, H. Berger, L. Araújo-Bazan, E. A. Espeso, R. Pachlinger, A. Gallmetzer, I. Anderl, C. Scazzocchio, and J. Strauss. 2007. Nuclear export of the transcription factor NirA is a regulatory checkpoint for nitrate induction in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27791-802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biswas, S., M. Roy, and A. Datta. 2003. N-acetylglucosamine-inducible CaGAP1 encodes a general amino acid permease which co-ordinates external nitrogen source response and morphogenesis in Candida albicans. Microbiology 1492597-2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calcagno-Pizarelli, A. M., S. Negrete-Urtasun, S. H. Denison, J. D. Rudnicka, H. J. Bussink, T. Múnera-Huertas, L. Stanton, A. Hervás-Aguilar, E. A. Espeso, J. Tilburn, H. N. Arst, Jr., and M. A. Peñalva. 2007. Establishment of the ambient pH signaling complex in Aspergillus nidulans: PalI assists plasma membrane localization of PalH. Eukaryot. Cell 62365-2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen, B. 1973. Regulation of intracellular and extracellular neutral and alkaline proteases in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 79311-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cove, D. 1966. The induction and repression of nitrate reductase in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 11351-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cultrone, A., Y. R. Dominguez, C. Drevet, C. Scazzocchio, and R. Fernández-Martín. 2007. The tightly regulated promoter of the xanA gene of Aspergillus nidulans is included in a helitron. Mol. Microbiol. 631577-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cybis, J., and P. Weglenski. 1972. Arginase induction in Aspergillus nidulans. The appearance and decay of the coding capacity of messenger. Eur. J. Biochem. 30262-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delcasso-Tremousaygue, D., F. Grellet, F. Panabieres, E. D. Ananiev, and M. Delseny. 1988. Structural and transcriptional characterization of the external spacer of a ribosomal RNA nuclear gene from a higher plant. Eur. J. Biochem. 172767-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Didion, T., B. Regenberg, M. U. J.ørgensen, M. C. Kielland-Brandt, and H. A. Andersen. 1998. The permease homologue Ssy1p controls the expression of amino acid and peptide transporter genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 27643-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emr, S. D., and S. Rieder. 2001. Overview of subcellular fractionation procedures for the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Protocols Cell Biol. 3.73.7.1-3.7.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erpapazoglou, Z., P. Kafasla, and V. Sophianopoulou. 2006. The product of the SHR3 orthologue of Aspergillus nidulans has restricted range of amino acid transporter targets. Fungal Genet. Biol. 43222-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forsberg, H., and P. O. Ljungdahl. 2001. Genetic and biochemical analysis of the yeast plasma membrane Ssy1p-Ptr3p-Ssy5p sensor of extracellular amino acids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21814-826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilstring, C. F., M. Melin-Larsson, and P. O. Ljungdahl. 1999. Shr3p mediates specific COPII coatomer-cargo interactions required for the packaging of amino acid permeases into ER-derived transport vesicles. Mol. Biol. Cell 103549-3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gómez, D., I. Garia, and C. Scazzocchio, and B. Cubero. 2003. Multiple GATA sites: protein binding and physiological relevance for the regulation of the proline transporter gene of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 50277-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green, N., H. Alexander, A. Olson, S. Alexander, T. M. Shinnick, J. G. Sutcliffe, and R. A. Lerner. 1982. Immunogenic structure of the influenza virus hemagglutinin. Cell 28477-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hein, C., J. Y. Springael, C. Volland, R. Haguenauer-Tsapis, and B. André. 1995. NPl1, an essential yeast gene involved in induced degradation of Gap1 and Fur4 permeases, encodes the Rsp5 ubiquitin-protein ligase. Mol. Microbiol. 1877-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoshikawa, C., M. Shichiri, S. Nakamori, and H. Takagi. 2003. A nonconserved Ala401 in the yeast Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase is involved in degradation of Gap1 permease and stress-induced abnormal proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10011505-11510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hynes, M. 1973. Alterations in the control of glutamate uptake in mutants of Aspergillus nidulans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 54685-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jack, D. L., I. T. Paulsen, and M. H. Saier. 2000. The amino acid/polyamine/organocation (APC) superfamily of transporters specific for amino acids, polyamines and organocations. Microbiology 146(Pt. 8)1797-1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinghorn, J. R., and J. Pateman. 1975. Mutations which affect amino acid transport in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 86174-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klasson, H., G. R. Fink, and P. O. Ljungdahl. 1999. Ssy1p and Ptr3p are plasma membrane components of a yeast system that senses extracellular amino acids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 195405-5416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kota, J., C. F. Gilstring, and P. O. Ljungdahl. 2007. Membrane chaperone Shr3 assists in folding amino acid permeases preventing precocious ERAD. J. Cell Biol. 176617-628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kota, J., and P. O. Ljungdahl. 2005. Specialized membrane-localized chaperones prevent aggregation of polytopic proteins in the ER. J. Cell Biol. 16879-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kudla, B., M. X. Caddick, T. Langdon, N. M. Martinez-Rossi, C. F. Bennett, S. Sibley, R. W. Davies, and H. N. Arst, Jr. 1990. The regulatory gene areA mediating nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Mutations affecting specificity of gene activation alter a loop residue of a putative zinc finger. EMBO J. 91355-1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ljungdahl, P. O., C. J. Gimeno, C. A. Styles, and G. R. Fink. 1992. SHR3: a novel component of the secretory pathway specifically required for localization of amino acid permeases in yeast. Cell 71463-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lockington, R. A., H. M. Sealy-Lewis, C. Scazzocchio, and R. W. Davies. 1985. Cloning and characterization of the ethanol utilization regulon in Aspergillus nidulans. Gene 33137-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magasanik, B., and C. A. Kaiser. 2002. Nitrogen regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 2901-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malkus, P., F. Jiang, and R. Schekman. 2002. Concentrative sorting of secretory cargo proteins into COPII-coated vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 159915-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Margolis-Clark, E., I. Hunt, S. Espinosa, and B. J. Bowman. 2001. Identification of the gene at the pmg locus, encoding system II, the general amino acid transporter in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 33127-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morozov, I. Y., M. Galbis-Martinez, M. G. Jones, and M. X. Caddick. 2001. Characterization of nitrogen metabolite signalling in Aspergillus via the regulated degradation of areA mRNA. Mol. Microbiol. 42269-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muro-Pastor, M. I., J. Strauss, A. Ramón, and C. Scazzocchio. 2004. A paradoxical mutant GATA factor. Eukaryot. Cell 3393-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nayak, T., E. Szewczyk, C. E. Oakley, A. Osmani, L. Ukil, S. L. Murray, M. J. Hynes, S. A. Osmani, and B. R. Oakley. 2006. A versatile and efficient gene-targeting system for Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 1721557-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niman, H. L., R. A. Houghten, L. E. Walker, R. A. Reisfeld, I. A. Wilson, J. M. Hogle, and R. A. Lerner. 1983. Generation of protein-reactive antibodies by short peptides is an event of high frequency: implications for the structural basis of immune recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 804949-4953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oakley, C. E., C. F. Weil, P. L. Kretz, and B. R. Oakley. 1987. Cloning of the riboB locus of Aspergillus nidulans. Gene 53293-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pantazopoulou, A., N. Lemuh, D. G. Hatzinikolaou, C. Drevet, G. Cecchetto, C. Scazzocchio, and G. Diallinas. 2007. Differential physiological and developmental expression of the UapA and AzgA purine transporters in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44627-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pateman, J. A., J. R. Kinghorn, and E. Dunn. 1974. Regulatory aspects of l-glutamate transport in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Bacteriol. 119534-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petersson, J., J. Pattison, A. L. Kruckeberg, J. A. Berden, and B. L. Persson. 1999. Intracellular localization of an active green fluorescent protein-tagged Pho94 phosphate permease in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 46237-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Platt, A., T. Langdon, H. N. Arst, Jr., D. Kirk, D. Tollervey, J. M. Sanchez, and M. X. Caddick. 1996. Nitrogen metabolite signalling involves the C-terminus and the GATA domain of the Aspergillus transcription factor AREA and the 3′ untranslated region of its mRNA. EMBO J. 152791-2801. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pontecorvo, G., J. A. Roper, L. M. Hemmons, K. D. MacDonald, and A. W. Bufton. 1953. The genetics of Aspergillus nidulans. Adv. Genet. 5141-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ravagnani, A., L. Gorfinkiel, T. Langdon, G. Diallinas, E. Adjadj, S. Demais, D. Gorton, H. N. Arst, Jr., and C. Scazzocchio. 1997. Subtle hydrophobic interactions between the seventh residue of the zinc finger loop and the first base of an HGATAR sequence determine promoter-specific recognition by the Aspergillus nidulans GATA factor AreA. EMBO J. 163974-3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Regenberg, B., S. Holmberg, L. D. Olsen, and M. C. Kielland-Brandt. 1998. Dip5p mediates high-affinity and high-capacity transport of l-glutamate and l-aspartate in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 33171-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Regenberg, B., and M. C. Kielland-Brandt. 2001. Amino acid residues important for substrate specificity of the amino acid permeases Can1p and Gnp1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 181429-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reggiori, F., and H. R. Pelham. 2002. A transmembrane ubiquitin ligase required to sort membrane proteins into multivesicular bodies. Nat. Cell Biol. 4117-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Risinger, A. L., and C. A. Kaiser. 2008. Different ubiquitin signals act at the Golgi and plasma membrane to direct GAP1 trafficking. Mol. Biol. Cell 192962-2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinson, J. H., C. Antony, and W. T. Drabble. 1973. The acidic amino-acid permease of Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 7953-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robinson, J. H., C. Antony, and W. T. Drabble. 1973. Regulation of the acidic amino-acid permease of Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 7965-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saier, M. J. 2000. A functional-phylogenetic classification system for transmembrane solute transporters. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64354-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 55.Scazzocchio, C. 1994. The purine degradation pathway, genetics, biochemistry and regulation. Prog. Ind. Microbiol. 29221-257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scazzocchio, C., and A. J. Darlington. 1968. The induction and repression of the enzymes of purine breakdown in Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 166557-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sophianopoulou, V., and C. Scazzocchio. 1989. The proline transport protein of Aspergillus nidulans is very similar to amino acid transporters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 3705-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sorkin, A. 2004. Cargo recognition during clathrin-mediated endocytosis: a team effort. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16392-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Southern, E. 1975. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J. Mol. Biol. 98503-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stanbrough, M., and B. Magasanik. 1995. Transcriptional and posttranslational regulation of the general amino acid permease of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 17794-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tavoularis, S., C. Scazzocchio, and V. Sophianopoulou. 2001. Functional expression and cellular localization of a green fluorescent protein-tagged proline transporter in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 33115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tavoularis, S. N., U. Tazebay, G. Diallinas, M. Sideridou, A. Rosa, C. Scazzocchio, and V. Sophianopoulou. 2003. Mutational analysis of the major proline transporter (PrnB) of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Membr. Biol. 20285-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tazebay, U. H., V. Sophianopoulou, B. Cubero, C. Scazzocchio, and G. Diallinas. 1995. Post-transcriptional control and kinetic characterization of proline transport in germinating conidiospores of Aspergillus nidulans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 13227-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tazebay, U. H., V. Sophianopoulou, C. Scazzocchio, and G. Diallinas. 1997. The gene encoding the major proline transporter of Aspergillus nidulans is upregulated during conidiospore germination and in response to proline induction and amino acid starvation. Mol. Microbiol. 24105-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tilburn, J., C. Scazzocchio, G. G. Taylor, J. H. Zabicky-Zissman, R. A. Lockington, and R. W. Davies. 1983. Transformation by integration in Aspergillus nidulans. Gene 26205-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Todd, R. B., J. A. Fraser, K. H. Wong, M. A. Davis, and M. J. Hynes. 2005. Nuclear accumulation of the GATA factor AreA in response to complete nitrogen starvation by regulation of nuclear export. Eukaryot. Cell 41646-1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Trip, H., M. E. Evers, and A. J. Driessen. 2004. PcMtr, an aromatic and neutral aliphatic amino acid permease of Penicillium chrysogenum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1667167-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trip, H., M. E. Evers, J. A. K. W. Kiel, and A. J. M. Driessen. 2004. Uptake of the β-lactam precursor α-aminoadipic acid in Penicillium chrysogenum is mediated by the acidic and the general amino acid permease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 704775-4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Trip, H., M. E. Evers, W. N. Konings, and A. J. Driessen. 2002. Cloning and characterization of an aromatic amino acid and leucine permease of Penicillium chrysogenum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 156573-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Valdez-Taubas, J., G. Diallinas, C. Scazzocchio, and A. L. Rosa. 2000. Protein expression and subcellular localization of the general purine transporter UapC from Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 30105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Valdez-Taubas, J., L. Harispe, C. Scazzocchio, L. Gorfinkiel, and A. L. Rosa. 2004. Ammonium-induced internalisation of UapC, the general purine permease from Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 4142-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vasseur, V., M. Van Montagu, and G. H. Goldman. 1995. Trichoderma harzianum genes induced during growth on Rhizoctonia solani cell walls. Microbiology 141(Pt. 4)767-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weidner, G., C. d'Enfert, A. Koch, P. C. Mol, and A. A. Brakhage. 1998. Development of a homologous transformation system for the human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus based on the pyrG gene encoding orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase. Curr. Genet. 33378-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wiame, J. M., M. Grenson, and H. N. Arst, Jr. 1985. Nitrogen catabolite repression in yeasts and filamentous fungi. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 261-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]