Abstract

Peroxisomal localization of the third enzyme of the penicillin biosynthesis pathway of Aspergillus nidulans, acyl-coenzyme A:IPN acyltransferase (IAT), is mediated by its atypical peroxisomal targeting signal 1 (PTS1). However, mislocalization of IAT by deletion of either its PTS1 or of genes encoding proteins involved in peroxisome formation or transport does not completely abolish penicillin biosynthesis. This is in contrast to the effects of IAT mislocalization in Penicillium chrysogenum.

The production of penicillin has been reported only for Aspergillus nidulans and Penicillium chrysogenum since both filamentous fungi possess acyl-coenzyme A (CoA):IPN acyltransferase (IAT; encoded by the aatA [penDE] gene) as one prerequisite for converting isopenicillin N to penicillin by exchange of the hydrophilic l-α-aminoadipic acid side chain for a hydrophobic acyl group (2, 4). Based on transcriptome analyses, in P. chrysogenum a substantial contribution of peroxisomes—single-membrane organelles containing specialized enzymes involved in a wide range of metabolic activities—to penicillin production was recently suggested (21). Whereas for this fungus the importance of IAT localization within functional peroxisomes has been shown (14), the contribution of these organelles to penicillin biosynthesis in A. nidulans has been studied only in connection with the cytoplasmic protein AatB, which is also involved in penicillin biosynthesis in A. nidulans (16). This study already hinted that peroxisomes are not absolutely essential for penicillin biosynthesis in A. nidulans, a theory the present study is focused on. Differences between these species are also important from an applied point of view since most basic research is done with the model organism A. nidulans whereas P. chrysogenum is used for industrial production.

Peroxins are proteins required for peroxisome biogenesis and division and for import of proteins into the peroxisomal matrix (15). Attempts to isolate P. chrysogenum peroxin deletion mutants have so far not been successful (8, 9). However, high peroxisome abundance caused by overproduction of peroxin Pc-Pex11p led to a twofold increase in penicillin production (10), emphasizing the importance of these organelles for P. chrysogenum. Recently, different A. nidulans peroxin mutant strains have been characterized (7). Of particular interest for the present study were the mutant unable to form peroxisomal structures caused by a disruption of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae pex3 ortholog (pexC::bar strain) and mutants impaired in import of matrix proteins carrying peroxisomal targeting signal 1 (PTS1) or PTS2 (pexEΔ and pexG14 strains, respectively) due to deletion/mutation of the respective receptors PexE and PexG (13, 17).

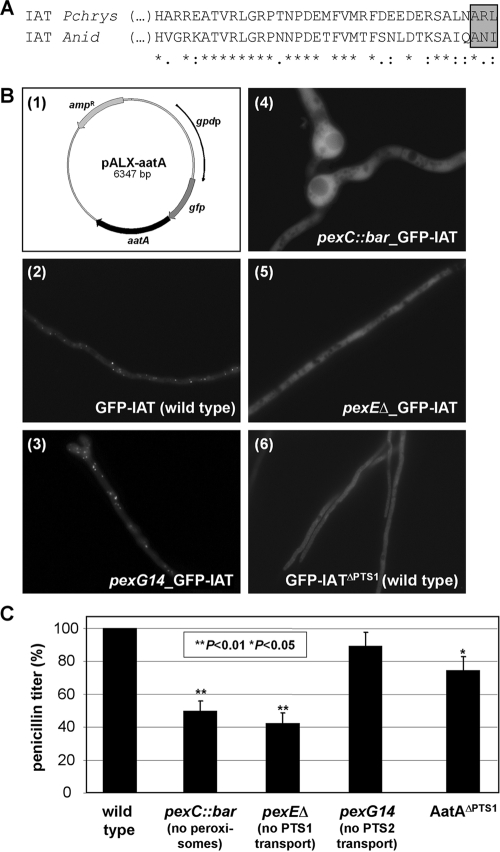

Usually, PTS1 sequences comprise three C-terminal amino acids of the form (S/A)(R/K)(L/M) although the context of the C-terminal sequence can greatly affect targeting (5). As depicted in Fig. 1A, the P. chrysogenum but not the A. nidulans IAT possesses such a motif. However, some peroxisomal proteins have cryptic PTS1 sequences (see, e.g., reference 11). By transformation of different A. nidulans strains (1) with a gfp-aatA gene fusion carried on plasmid pALX-aatA (Fig. 1B1) (18) and subsequent fluorescence microscopy, we showed that localization of the A. nidulans IAT is PTS1 dependent (Fig. 1B2 to 5) (strains are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material). Compared to its mainly peroxisomal localization in the wild-type strain, indicated by punctate dots (Fig. 1B2), mislocalization of the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-IAT fusion protein was observed in strains without peroxisomal structures (pexC::bar strain) (Fig. 1B4) and without PTS1 import (pexEΔ strain) (Fig. 1B5). The effects of these peroxin mutations clearly defined the punctate dots of the wild-type strain as peroxisomes. Localization was unaffected in the pexG14 strain, which lacked PTS2 import (Fig. 1B3). Thus, PTS1 and not PTS2 targeting is responsible for localizing IAT to peroxisomes. Additionally, the atypical putative PTS1 sequence (ANI) is essential for this import, because a deletion of this sequence (GFP-IATΔPTS1) led to mislocalization of the protein in the wild-type strain (Fig. 1B6). We therefore conclude that the A. nidulans IAT is transported to the peroxisomes via its atypical PTS1 by the PexE-dependent import machinery.

FIG. 1.

IAT localization and penicillin production in A. nidulans. (A) Sequence alignment of the IAT C termini of P. chrysogenum (gene accession number ABA70584) and A. nidulans (gene accession number AN2623.4) with ClustalW (6). *, identical residues; :, conserved; ., semiconserved. Whereas the P. chrysogenum IAT possesses a conserved PTS1 motif (boxed), the A. nidulans one is atypical. (B) Localization of GFP-IAT in wild-type A. nidulans (B2) and the peroxin mutant pexG14 (B3), pexC::bar (B4), and pexEΔ (B5) strains. Strains were transformed with plasmid pALX-aatA (B1), encoding a GFP-IAT fusion protein. When biogenesis of peroxisomes or PTS1 (but not PTS2-)-mediated import was affected, GFP-IAT was not localized to peroxisomes. This was also observed in the wild type producing GFP-IAT that lacked the PTS1 (GFP-IATΔPTS1; B6). Genotypes of the strains are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. (C) Penicillin titers of wild-type A. nidulans (set at 100%), peroxin mutants (7), and the AatAΔPTS1 strain, in which the aatA gene was replaced by an aatA allele lacking the PTS1-encoding sequence (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Statistical significance is indicated by the P value, as calculated by Student's t test. Whenever IAT was mislocalized (see panel B), penicillin production was reduced but not abolished. Penicillin titers were assayed as described previously (3).

It has been shown previously that disruption of the aatA gene has a severe impact on penicillin biosynthesis in A. nidulans, with biosynthesis yielding only minimal amounts (below 20% in a bioassay) due to AatB activity (16). In P. chrysogenum, however, mutants possessing a mislocalized IAT failed to produce penicillin (14). Therefore, penicillin production by the A. nidulans peroxin mutants (7) and by a strain in which the aatA gene was replaced by an aatA allele lacking the PTS1-encoding sequence (AatAΔPTS1; generated in this study by homologous integration) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) was assayed (3) (Fig. 1C). Mislocalization of IAT due to mutations of peroxins or the enzyme itself resulted in a decrease of the penicillin titer (compare to Fig. 1B). However, this decrease was much smaller than that in a strain completely lacking aatA-encoded IAT (16), indicating that the mislocalized IAT is at least partially functional. Furthermore, a strain without peroxisomes (pexC::bar strain) was still able to produce penicillin. The penicillin titers of a strain lacking the PTS1 transporter (pexEΔ strain) were reduced to 50% of wild-type levels, whereas the mutation of the PTS2 transporter in the pexG14 strain had no significant effect. A similar reduction in penicillin production was also observed in mutants impaired in both PTS1- and PTS2-mediated import (pexA9, pexF23, and pexM15 strains) (7) (data not shown). This suggested that, in A. nidulans, transport of the peroxisomal proteins involved in penicillin biosynthesis, either directly or indirectly, is mainly PTS1 dependent. But the proper localization of these proteins and, moreover, the presence of functional peroxisomes are not absolutely required for penicillin production. The beneficial role of peroxisomes was further confirmed by the reduced penicillin production of a strain with only a small number of enlarged peroxisomes caused by deletion of pexK (7), the ortholog of Pc-pex11 (data not shown).

Besides IAT, one of the peroxisomal proteins involved in penicillin biosynthesis could be the PTS1 containing AN7631.4, a proposed homolog of the P. chrysogenum phenylacetyl-CoA ligase (Phl) which was shown to affect penicillin biosynthesis in P. chrysogenum by supplying IAT with phenylacetyl-CoA (12). However, disruption of the associated gene in A. nidulans had no clear effect on penicillin biosynthesis (data not shown). It is likely that this is due to redundant enzymes, which are predicted to be both peroxisomal (e.g., enzymes encoded by genes with accession no. AN5990.4 and AN11034.4) and cytoplasmic (e.g., enzymes encoded by genes with accession no. AN2549.4 and AN3490.4). Phl-like cytoplasmic enzyme activity could also provide a mislocated IAT with acyl-CoA, thus enabling penicillin production in A. nidulans.

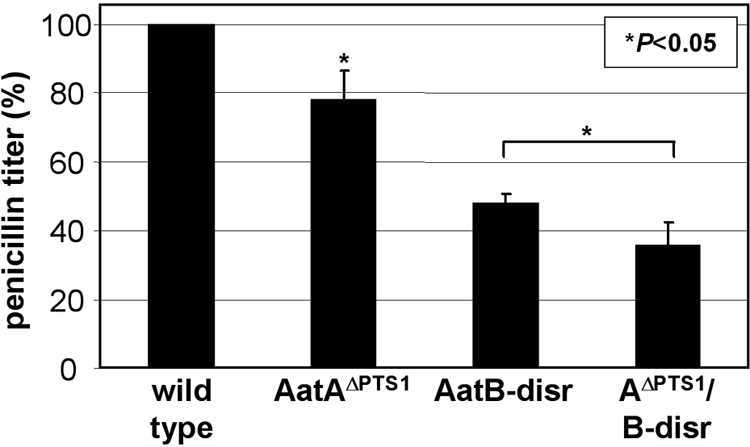

In contrast to what was found for P. chrysogenum, mislocalization of IAT in strain AatAΔPTS1 did reduce but did not abolish penicillin biosynthesis (Fig. 1C), leading to the hypothesis that the A. nidulans IAT is also functional in the cytoplasm but may possess reduced activity. As mentioned above, we recently identified a cytoplasmic IAT-like protein (AatB) involved in penicillin production and showed that only inactivation of both the peroxisomal IAT and the cytoplasmic AatB reduced the penicillin titer to below the liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry detection level (16). To rule out the possibility that residual penicillin production by the AatAΔPTS1 strain was due only to AatB activity, the strain was crossed (20) with the aatB disruption AatB-disr strain (16) and penicillin production of the parental strains and a strain carrying both mutant genes (AΔPTS1/B-disr strain) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) was analyzed (Fig. 2). The double mutant was still able to produce penicillin, and production compared to that of the AatB-disr strain was significantly decreased; the extent of the reduction (approximately 20%) was the same as that for the AatAΔPTS1 strain compared to the wild-type strain. Therefore, the impact of the mislocalized IAT was the same for both strains and independent of AatB activity. Taken together, these data indicate that, in A. nidulans, despite reduced activity, a mislocalized IAT is still functional. Obviously, differences in the cellular environment are better tolerated by the A. nidulans IAT than by the P. chrysogenum IAT; this is presumably due to sequence differences (19).

FIG. 2.

Penicillin titer of A. nidulans AatΔPTS1/B-disr strain (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) compared to those of the wild type (set at 100%) and parental AatAΔPTS1 and AatB-disr strains (16). Statistical significance is indicated by the P value. Since the AΔPTS1/B-disr strain still produced penicillin, production by the AatAΔPTS1 strain was not due to AatB alone.

However, it is clear that the contribution of peroxisomes to penicillin biosynthesis in A. nidulans is more than the provision of a better environment for IAT function, since absence of peroxisome formation or of the essential PTS1 transport led to a more severe reduction of the penicillin titer (Fig. 1C). In these strains, mislocalization of additional peroxisomal proteins might provoke metabolic impairments that indirectly influence penicillin production. Therefore, compartmentalization of the final step seems to be advantageous with respect to the yield of the whole process. It is likely that keeping enzymes and substrates in close proximity or facilitating the catalyzed reactions, e.g., the exchange for a hydrophobic acyl side chain, by the more hydrophobic environment within the peroxisomes could increase efficiency of penicillin production. In addition, the slightly alkaline pH of the peroxisomal lumen (22, 23) might also contribute to this increase. Overall, this study has shown that the necessity for IAT being localized to functional peroxisomes in A. nidulans is different from that in P. chrysogenum. A detailed analysis of both the enzyme activity tolerance and the range of phenylacetyl-CoA ligases is necessary for elucidating this unexpected discrepancy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandra Murray for excellent research assistance.

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council, a DAAD scholarship for Ph.D. students granted to P.S., and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Priority Program SPP1152).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 January 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballance, D. J., and G. Turner. 1985. Development of a high-frequency transforming vector for Aspergillus nidulans. Gene 36321-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brakhage, A. A. 1998. Molecular regulation of beta-lactam biosynthesis in filamentous fungi. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62547-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brakhage, A. A., P. Browne, and G. Turner. 1992. Regulation of Aspergillus nidulans penicillin biosynthesis and penicillin biosynthesis genes acvA and ipnA by glucose. J. Bacteriol. 1743789-3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brakhage, A. A., P. Spröte, Q. Al-Abdallah, A. Gehrke, H. Plattner, and A. Tüncher. 2004. Regulation of penicillin biosynthesis in filamentous fungi. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 8845-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brocard, C., and A. Hartig. 2006. Peroxisome targeting signal 1: is it really a simple tripeptide? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 17631565-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chenna, R., H. Sugawara, T. Koike, R. Lopez, T. J. Gibson, D. G. Higgins, and J. D. Thompson. 2003. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 313497-3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hynes, M. J., S. L. Murray, G. S. Khew, and M. A. Davis. 2008. Genetic analysis of the role of peroxisomes in the utilization of acetate and fatty acids in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 1781355-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiel, J. A., R. E. Hilbrands, R. A. Bovenberg, and M. Veenhuis. 2000. Isolation of Penicillium chrysogenum PEX1 and PEX6 encoding AAA proteins involved in peroxisome biogenesis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 54238-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiel, J. A., M. van den Berg, R. A. Bovenberg, I. J. van der Klei, and M. Veenhuis. 2004. Penicillium chrysogenum Pex5p mediates differential sorting of PTS1 proteins to microbodies of the methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41708-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiel, J. A., I. J. van der Klei, M. A. van den Berg, R. A. Bovenberg, and M. Veenhuis. 2005. Overproduction of a single protein, Pc-Pex11p, results in 2-fold enhanced penicillin production by Penicillium chrysogenum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42154-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein, A. T., M. van den Berg, G. Bottger, H. F. Tabak, and B. Distel. 2002. Saccharomyces cerevisiae acyl-CoA oxidase follows a novel, non-PTS1, import pathway into peroxisomes that is dependent on Pex5p. J. Biol. Chem. 27725011-25019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamas-Maceiras, M., I. Vaca, E. Rodriguez, J. Casqueiro, and J. F. Martin. 2006. Amplification and disruption of the phenylacetyl-CoA ligase gene of Penicillium chrysogenum encoding an aryl-capping enzyme that supplies phenylacetic acid to the isopenicillin N-acyltransferase. Biochem. J. 395147-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazarow, P. B. 2006. The import receptor Pex7p and the PTS2 targeting sequence. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 17631599-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müller, W. H., R. A. Bovenberg, M. H. Groothuis, F. Kattevilder, E. B. Smaal, L. H. Van der Voort, and A. J. Verkleij. 1992. Involvement of microbodies in penicillin biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1116210-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Platta, H. W., and R. Erdmann. 2007. Peroxisomal dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 17474-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spröte, P., M. J. Hynes, P. Hortschansky, E. Shelest, D. H. Scharf, S. M. Wolke, and A. A. Brakhage. 2008. Identification of the novel penicillin biosynthesis gene aatB of Aspergillus nidulans and its putative evolutionary relationship to this fungal secondary metabolism gene cluster. Mol. Microbiol. 70445-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanley, W. A., and M. Wilmanns. 2006. Dynamic architecture of the peroxisomal import receptor Pex5p. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 17631592-1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szewczyk, E., A. Andrianopoulos, M. A. Davis, and M. J. Hynes. 2001. A single gene produces mitochondrial, cytoplasmic, and peroxisomal NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Biol. Chem. 27637722-37729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tobin, M. B., M. D. Fleming, P. L. Skatrud, and J. R. Miller. 1990. Molecular characterization of the acyl-coenzyme A:isopenicillin N acyltransferase gene (penDE) from Penicillium chrysogenum and Aspergillus nidulans and activity of recombinant enzyme in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1725908-5914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Todd, R. B., M. A. Davis, and M. J. Hynes. 2007. Genetic manipulation of Aspergillus nidulans: meiotic progeny for genetic analysis and strain construction. Nat. Protoc. 2811-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Berg, M. A., R. Albang, K. Albermann, J. H. Badger, J. M. Daran, A. J. Driessen, C. Garcia-Estrada, N. D. Fedorova, D. M. Harris, W. H. Heijne, V. Joardar, J. A. Kiel, A. Kovalchuk, J. F. Martin, W. C. Nierman, J. G. Nijland, J. T. Pronk, J. A. Roubos, I. J. van der Klei, N. N. van Peij, M. Veenhuis, H. von Dohren, C. Wagner, J. Wortman, and R. A. Bovenberg. 2008. Genome sequencing and analysis of the filamentous fungus Penicillium chrysogenum. Nat. Biotechnol. 261161-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Lende, T. R., P. Breeuwer, T. Abee, W. N. Konings, and A. J. Driessen. 2002. Assessment of the microbody luminal pH in the filamentous fungus Penicillium chrysogenum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1589104-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Roermund, C. W., M. de Jong, L. Ijlst, J. van Marle, T. B. Dansen, R. J. Wanders, and H. R. Waterham. 2004. The peroxisomal lumen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is alkaline. J. Cell Sci. 1174231-4237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.