Abstract

Ewing’s sarcoma (ES) is a neoplasm of undifferentiated small round cells, which occurs in the bones and deep soft tissues of children and adolescents. We present a rare case of a 44-year-old woman with gastric ES presenting with epigastric pain and weight loss. Ultrasound and computed tomography scans indicated a solid/cystic mass in the pancreatic tail. At laparotomy, the tumor was found attached to the posterior surface of the stomach, completely free from the pancreas, with no lymphadenopathy or local metastases. The polynodal, partly pseudocystic, dark-red soft tumor was excised. Histopathology revealed an anaplastic small-round-cell tumor with strong membranous CD99 immunoexpression. Additionally, there was patchy immunostaining for S-100 protein, vimentin, protein gene product (PGP) 9.5 and neuron-specific enolase, and weak focal CD117 cytoplasmic immunoreactivity. The patient had no adjuvant chemotherapy; her postoperative recovery was uneventful, and she remains symptom-free, and without any sign of recurrence at 20 mo. To the best of our knowledge, this is only the third ever case of gastric ES.

Keywords: Stomach, Extraskeletal, Ewing’s sarcoma

INTRODUCTION

Ewing’s sarcoma, or primitive neuroectodermal tumour (ES/PNET), is a neoplasm of undifferentiated small round cells that occurs in children, adolescents and young adults[1,2]. Although predominantly affecting the bones and deep soft tissues[2], these sarcomas are also being described as affecting the visceral organs, with increasing frequency. These extraskeletal ES/PNET sarcomas are histologically indistinguishable from the bony type[3], and have been documented in the pancreas[4,5], vagina[6], rectovaginal septum[7], small bowel[8,9], prostate[10], ovaries[11], esophagus[12], and kidney[13]. Two cases of gastric ES/PNET have been previously reported: the first in a 14-year-old boy[14] and the second in a 66-year-old woman[2]. We describe the third ever case of gastric ES.

CASE REPORT

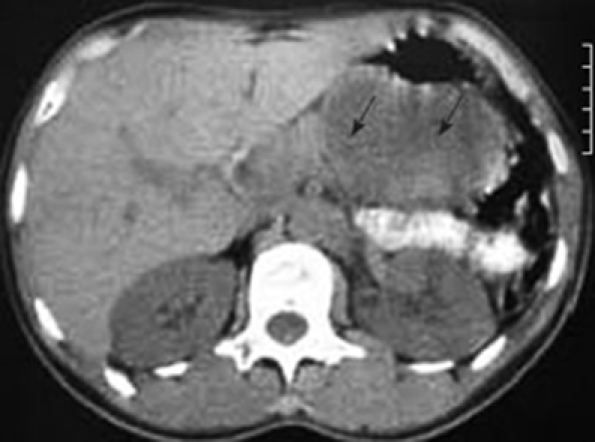

In January 2006, a 44-year-old obese woman presented with a 6-mo history of epigastric pain and weight loss of 5 kg. On examination, she had only mild tenderness in the epigastrium. All standard laboratory data were within normal limits, though fasting cholesterol was elevated at 6.80 μmol/L (normal range 3.1-6.4 μmol/L), and fasting triglyceride was 2.30 mmol/L (normal < 1.95 mmol/L); erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 14 mm/h. Ultrasonography (US) and computed tomography (CT) scans (Figure 1) confirmed a solid/cystic mass measuring 66 mm × 46 mm in the tail of the pancreas.

Figure 1.

CT scan indicating a tumor at the tail of the pancreas (arrows).

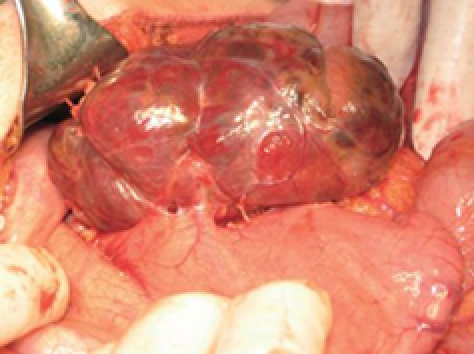

The patient underwent laparotomy for the tumor at the tail of the pancreas; but, at operation, the only pathology found within the abdomen was a mass along the posterior wall of the stomach (Figure 2). There was no lymphadenopathy in the vicinity of the tumor or the upper retroperitoneum. The tumor was dark-red in color, moderately soft, covered by a thin light-grey membrane, and adherent to the stomach along a surface of 3 cm × 3 cm. Intraoperative frozen section biopsy failed to clarify either the tumor type or the eventual malignant potential. Thus, when the tumor was completely excised, and no significant damage was seen on the stomach wall, the decision was made to not proceed to a gastric resection.

Figure 2.

Photograph showing the tumor on the posterior wall of the stomach.

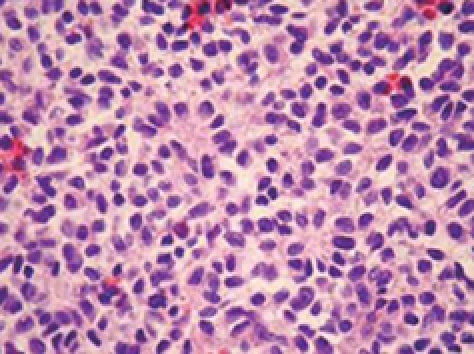

The pathological specimen measured 10 cm in its greatest diameter. On gross inspection, the cut surface showed large central hemorrhagic and necrotic changes and pseudocystic degeneration. The tumor tissue was largely light grey and solid, with some softer and more friable, reddish congested areas (Figure 3). Microscopic examination revealed a hypercellular diffuse, and rather monotonous proliferation of small round cells with clear cytoplasm and relative nuclear uniformity. However, there were also areas showing nuclear atypia and abortive pseudorosette formation (Figure 4). Microcystic and hemorrhagic changes were seen on most of the sections, as well as sharply demarcated borders frequently covered by intact serosa. Tumor necrosis was minimal, although atypical mitotic figures were seen with a mitotic index of 14 per 50 high power fields.

Figure 3.

Photograph showing a cross section of the tumor.

Figure 4.

Histological appearance of the diffuse neoplastic infiltration showing rather uniform diffuse small round cells and abortive pseudorosette formation (HE, × 112).

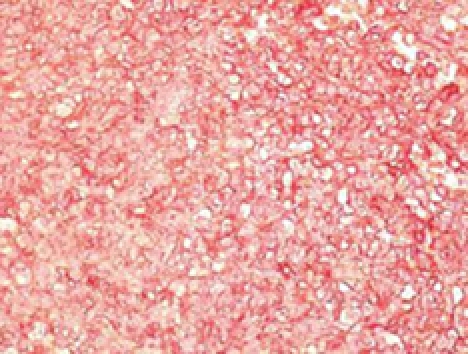

Immunohistochemical examination with monoclonal antibodies excluded most of the differential diagnoses. Immunostaining was negative for pancytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), leukocyte common antigen, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, desmin, muscle-specific antigen, the α subunit of smooth muscle antigen (SMA), glial fibrilar acidic protein, neurofilament protein, α-inhibin, melanin A and CD34. The diagnosis of ES/PNET was established by the presence of strong membranous CD99 immunoexpression by the vast majority of tumor cells (Figure 5), in addition to clear, but patchy S-100 protein, vimentin, protein gene product (PGP) 9.5 and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) immunostaining, as well as weak focal CD117 cytoplasmic immunoreactivity in very few neoplastic cells. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) was not available to us.

Figure 5.

Tumor cells showing strong diffuse membrane immuno-histochemical reactivity with CD99 antibodies [labeled streptavidin biotin (LSAB+) method, 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole (AEC) visualization, × 112].

The patient did not receive any adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy; her postoperative recovery was unevent-ful, and she remains symptom-free and without recurrence on US or CT scan 20 mo later.

DISCUSSION

Histologically, ES/PNET is composed of small round cells that are usually rich in glycogen, and the neuroepithelial morphologic differentiation is confirmed by pseudorosette formation. Immunohistochemically, the neuroendocrine phenotype is confirmed by positivity to CD99, and to NSE and S-100 to a lesser extent, as these are also found in a number of other small-round-cell tumors[2]. FISH testing for the presence of the t (11;12) translocation can be particularly useful when the tumor occurs in older patients or in an unusual site[2,15], as well as to differentiate from desmoplastic small round cell tumors (DSRCT)[15]. The ultimate diagnosis should be based on both histology and immunohistochemistry[16].

We considered several other small-round-cell tumors in our differential diagnoses. Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma, and small-cell osteosarcoma were excluded as no chondroid or osteoid differentiation was found. Embryonic rhabdomyosarcoma was excluded as all muscular markers were negative. Intra-abdominal desmoplastic round-cell tumor was excluded as cytokeratin and EMA markers were negative, and nodular dissemination was absent. Hemangiopericytoma, glomus and other perivascular tumors were excluded on the basis of CD34 and SMA negativity.

The results of surgery alone for extraskeletal ES are poor in most cases, while patients receiving multimodal chemotherapy and radiotherapy have a much better prognosis[17]. Through the combination of local surgical treatment and systemic chemotherapy, long-term survival has improved from 10% to 50%-60% or greater[18,19], although the pathologist and oncologist will need to decide whether treatment regimens for tumors are better based on their phenotype or their genotype, when these two profiles are seemingly in conflict[16].

The two previously published cases of ES of the stomach both had poor outcomes. A 14-year-old boy with gastric ES was also found to have a diffuse metastatic lesion in the liver. He underwent a subtotal gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy followed by chemotherapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor because of intense expression of CD117 (c-kit), but died[14]. A 66-year-old woman with ES within the antropyloric area of the stomach underwent a distal gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy, but despite adjuvant chemotherapy, she also died 10 mo postoperatively[2].

Following postoperative pathological analysis, our patient was presented to the oncologists, who decided not to give any adjuvant chemotherapy. Despite this, she remains clinically well, and without recurrence to the present day (20 mo later).

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Marc D Basson, MD, PhD, MBA, Chief of Surgery, John D. Dingell VA Medical Center, 4646 John R. Street, Detroit, MI 48301, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Kondo S, Yamaguchi U, Sakurai S, Ikezawa Y, Chuman H, Tateishi U, Furuta K, Hasegawa T. Cytogenetic confirmation of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor and ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor in a single patient. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:753–756. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soulard R, Claude V, Camparo P, Dufau JP, Saint-Blancard P, Gros P. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the stomach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:107–110. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-107-PNTOTS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom C, Lisbona A, Begin LR, Pollak M. Extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1995;46:131–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Movahedi-Lankarani S, Hruban RH, Westra WH, Klimstra DS. Primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the pancreas: a report of seven cases of a rare neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1040–1047. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200208000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danner DB, Hruban RH, Pitt HA, Hayashi R, Griffin CA, Perlman EJ. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor arising in the pancreas. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farley J, O’Boyle JD, Heaton J, Remmenga S. Extraosseous Ewing sarcoma of the vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:832–834. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petkovic M, Zamolo G, Muhvic D, Coklo M, Stifter S, Antulov R. The first report of extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma in the rectovaginal septum. Tumori. 2002;88:345–346. doi: 10.1177/030089160208800419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adair A, Harris SA, Coppen MJ, Hurley PR. Extraskeletal Ewings sarcoma of the small bowel: case report and literature review. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2001;46:372–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shek TW, Chan GC, Khong PL, Chung LP, Cheung AN. Ewing sarcoma of the small intestine. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23:530–532. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200111000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colecchia M, Dagrada G, Poliani PL, Messina A, Pilotti S. Primary primitive peripheral neuroectodermal tumor of the prostate. Immunophenotypic and molecular study of a case. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:e190–e193. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-e190-PPPNTO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawauchi S, Fukuda T, Miyamoto S, Yoshioka J, Shirahama S, Saito T, Tsukamoto N. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the ovary confirmed by CD99 immunostaining, karyotypic analysis, and RT-PCR for EWS/FLI-1 chimeric mRNA. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1417–1422. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199811000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maesawa C, Iijima S, Sato N, Yoshinori N, Suzuki M, Tarusawa M, Ishida K, Tamura G, Saito K, Masuda T. Esophageal extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:130–132. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.30219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jimenez RE, Folpe AL, Lapham RL, Ro JY, O’Shea PA, Weiss SW, Amin MB. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the kidney: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:320–327. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czekalla R, Fuchs M, Stolzle A, Nerlich A, Poremba C, Schaefer KL, Weirich G, Hofler H, Schneller F, Peschel C, et al. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the stomach in a 14-year-old boy: a case report. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1391–400. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200412000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner LJ, Ayala AG, Monforte HL, Dunphy CH. Ewing sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor: adult abdominal tumors with an Ewing sarcoma gene rearrangement demonstrated by fluorescence in situ hybridization in paraffin sections. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2004;12:160–165. doi: 10.1097/00129039-200406000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorner P, Squire J, Chilton-MacNeil S, Marrano P, Bayani J, Malkin D, Greenberg M, Lorenzana A, Zielenska M. Is the EWS/FLI-1 fusion transcript specific for Ewing sarcoma and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor? A report of four cases showing this transcript in a wider range of tumor types. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1125–1138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy JG, Eustace S, Caulfield R, Fennelly DJ, Hurson B, O’Rourke KS. Extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Spine. 2000;25:1996–1999. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200008010-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose JS, Hermann G, Mendelson DS, Ambinder EP. Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma with computed tomography correlation. Skeletal Radiol. 1983;9:234–237. doi: 10.1007/BF00354123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grier HE, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, Link MP, Fryer CJ, Pritchard DJ, Gebhardt MC, Dickman PS, Perlman EJ, Meyers PA, et al. Addition of ifosfamide and etoposide to standard chemotherapy for Ewing’s sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:694–701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]