Abstract

AIM: To indirectly determine if tissue transglutaminase (tTG)-specific T cells play a crucial role in the propagation of celiac disease.

METHODS: Anti-deamidated gliadin peptide (DGP) and anti-tTG IgA and IgG were measured in the sera of celiac patients (both untreated and treated). The correlations were determined by Spearman’s rank correlation test.

RESULTS: In celiac patients, we found a very significant correlation between the production of DGP IgA and IgG (r = 0.75), indicating a simultaneous and ongoing production of these two isotypes reminiscent of oral vaccination studies. However, there was far less association between the production of tTG IgA and tTG IgG in celiac patients (r = 0.52). While tTG IgA was significantly correlated with DGP IgA (r = 0.80) and DGP IgG (r = 0.67), there was a weak correlation between production of anti-tTG IgG and the production of anti-DGP IgA (r = 0.38) and anti-DGP IgG (r = 0.43).

CONCLUSION: These data demonstrate that the production of anti-tTG IgA is directly correlated to the production of anti-DGP IgG and IgA, whereas anti-tTG IgG is only weakly correlated. This result therefore supports the hapten-carrier theory that in well-established celiac patients anti-tTG IgA is produced by a set of B cells that are reacting against the complex of tTG-DGP in the absence of a tTG-specific T cell.

Keywords: Celiac disease, Tissue transglutaminase, Deamidated gliadin peptide, Correlation, IgG, IgA

INTRODUCTION

Celiac disease is a gluten-sensitive disease that afflicts primarily the small bowel, resulting in the shortening of villi, increased numbers of intraepithelial lymphocytes, and crypt hyperplasia[1,2]. One unique feature of celiac disease that is utilized as a diagnostic and screening tool is the production of IgA specific for tissue transglutaminase (tTG) that circulates in the blood[3]. It is unclear though, as to why these antibodies are generated when a celiac patient eats gluten. One association between tTG and gliadin is that intestinal T cells from celiac patients respond to specific gliadin peptides that have been deamidated, a process that is mediated by tTG binding to gliadin peptides[4]. Anti-tTG IgA is tightly associated with the development of enteropathy and brings into question whether it is a cause or consequence of enteropathy[5,6]. It is especially perplexing because many celiac patients will produce IgA against whole gliadin, a storage protein of gluten, yet this production has a much lower specificity for celiac disease than the anti-tTG IgA ELISA assay[7].

One theory for the origin of anti-tTG IgA was proposed in 1997[8]. This proposal was based on a hapten-carrier model wherein gliadin-specific T cells contribute to the stimulation of B cells that are specific for tTG. This would be achieved by the tTG-specific B cells internalizing complexes of tTG and gliadin peptides and later presenting gliadin epitopes to the gliadin-specific T cells. In this manner, gliadin-specific T cells would contribute to the tTG-specific B cells producing antibodies against tTG. At that time, this proposal was supported by a lack of evidence for tTG-specific T cells. It is notable that to this date, there is still no evidence that a tTG-specific T cell exists in the small intestine of celiac patients. Of course, it is difficult to prove the absence of a cell type. However, novel ELISAs have been recently developed that can detect antibodies against deamidated gliadin peptides (DGP) in celiac patients[9,10]. This allows us to look at this process in an indirect manner, by determining the correlation among the production of antibody isotypes against DGP and tTG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and study design

Serum samples were collected from patients referred to the division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA for the assessment of gastrointestinal symptoms, unexplained weight loss/anemia, or to rule out celiac disease. One hundred and twenty-one celiac patients were initially included in the study. We defined the diagnosis of celiac disease based on the presence of villous atrophy (enteropathy type IIIa or greater based on currently accepted diagnostic criteria) in histopathological examination of small intestinal biopsy[11,12]. Of 121 celiac patients who were initially included in the study, 10 were excluded because they had Marsh I enteropathy (n = 8) or IgA deficiency (n = 2). One hundred and ninety-four serum samples were collected from the remaining 111 biopsy-proven celiac patients. Ninety-two samples were collected before patients started treatment and 102 samples were collected while patients were on a gluten-free diet (GFD). The median (range) treatment with GFD was 10.5 (2-54) mo. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mayo Clinic.

Serology

Anti-DGP IgG and IgA were measured with “QUANTA Lite Gliadin-IgA II and Gliadin-IgG II” ELISA kits (INOVA Diagnostics Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-tTG IgA and IgG were measured using “BINDAZYME human IgA and IgG Anti-Tissue Transglutaminase EIA” ELISA kits (The Binding Site, Ltd., Birmingham, UK).

Statistical analysis

Correlations between the antibody titers were assessed by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients that were calculated using version 6.0.0 JMP software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

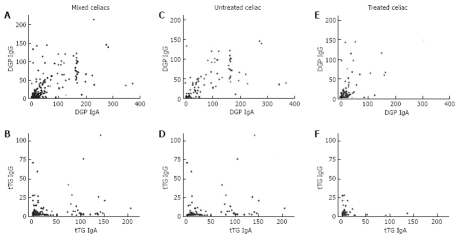

The production of IgA and IgG specific for DGP and tTG was evaluated in celiac patients and plotted such that a direct comparison was made between the production of IgG versus IgA for each antigen group and each patient group (Figure 1). There was a significantly stronger correlation between the production of IgA and IgG specific for DGP (r = 0.75) in celiac patients than those specific for tTG (r = 0.52). When untreated celiac patients (gluten-containing diet; GCD) were separated from treated celiac patients (GFD), the correlation coefficients in comparing anti-DGP IgG and IgA were 0.78 for GCD and 0.58 for GFD, whereas a significantly lower correlation was found for comparing anti-tTG IgG and IgA (r = 0.60 for GCD and r = 0.44 for GFD).

Figure 1.

Effect of diet upon isotype correlations. The titers of IgG and IgA against DGP and tTG were evaluated and plotted against each other for celiac patients. For mixed (treated and untreated) celiac patients, the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were r = 0.75 for DGP (A) and r = 0.52 for tTG (B). For untreated celiac patients, r = 0.78 for DGP (C) and r = 0.60 for tTG (D). For treated celiac patients, r = 0.58 for DGP (E) and r = 0.44 for tTG (F).

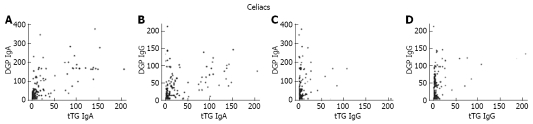

Comparisons were also made between the production of anti-tTG IgA and the production of DGP IgA and IgG in celiac patients (Figure 2). Anti-tTG IgA was highly correlated with the production of both anti-DGP IgA (r = 0.80) and DGP IgG (r = 0.67) which was similar to a previous finding[9].

Figure 2.

Comparing anti-tTG IgA and IgG production with anti-DGP IgA and IgG. The titers of anti-tTG IgA (A-B) and anti-tTG IgG (C-D) were compared with the titers of anti-DGP IgA (A and C) as well as anti-DGP IgG (B and D) in all treated and untreated celiac patients. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were 0.80 (A), 0.67 (B), 0.38 (C), and 0.43 (D).

Finally, comparisons were made between the production of anti-tTG IgG and the production of IgA and IgG specific for DGP. In contrast to anti-tTG IgA which was strongly correlated with DGP antibodies, anti-tTG IgG was weakly correlated with the production of anti-DGP IgA (r = 0.38) and anti-DGP IgG (r = 0.43).

DISCUSSION

The data presented in this manuscript support the theory that the generation of anti-tTG IgA is directly linked to the B cell immune response against DGP, possibly even the T-cell immune response to DGP as well. The reduced correlation in celiac patients between the production of anti-tTG IgG and anti-tTG IgA (r = 0.52) as compared to the production of anti-DGP IgG and anti-DGP IgA (r = 0.75) also demonstrates that there is a fundamental difference between the generation of antibody isotypes against the two antigens in celiac patients. Another difference between the production of IgG and IgA against DGP and tTG is that dietary gliadin mainly affects the production of both IgG and IgA against DGP, but not against both tTG IgG and IgA.

The lack of correlation between the production of anti-tTG IgG and anti-DGP IgG and IgA and anti-tTG IgA (Figures 1 and 2) therefore raises several questions. If the inflammatory T cells that are specific for deamidated gliadin are providing help to the B cells that are specific for a tTG/gliadin complex, why are not more tTG-specific B cells isotype class switching to IgG? One explanation is that the tTG/gliadin-specific B cell group in well-established celiac patients is fully committed to being IgA-positive. A memory B cell could be one such type of long lived IgA-positive B cell, and in this way, require minimal help from a bystander T cell response in order to be fully activated. It is notable that treated celiac patients will relapse with a gluten challenge, even after years of adhering to a GFD, indicating that there is a strong memory component of T cells, B cells, or both in celiac patients[13–15].

Also of interest are studies that demonstrated significant variability in the production of anti-tTG IgA in children. One study found that only six out of 14 celiac patients less than 2 years of age had anti-endomysial antibodies[16]. Another group reported markedly fluctuating levels of transglutaminase antibodies in children[17]. These data would indicate that anti-tTG antibodies do not develop immediately at the time of initial exposure to dietary gliadin, but instead develop after 1-2 (or more) years of continued gliadin exposure.

Our data, as well as the data from others, therefore support the hapten-carrier theory that a B cell that is specific for a tTG/gliadin complex is present in well-established celiac patients and is helped by gliadin-specific T cells. However, our data are also compatible with the model based on molecular mimicry between tTG and gliadin[9,18]. Indeed, it is our belief that the hapten-carrier model and molecular mimicry model are not exclusive. A potential “combined” model would be that a catalyst-like IgA+ memory B cell specific for regions that are shared between tTG and gliadin exists long term in well-established celiac patients. With the consumption of gliadin, these B cells would internalize tTG/gliadin complexes, become activated with minimal T cell help, and then present gliadin peptides to gliadin-specific T cells. This would result in the amplification of both deamidated gliadin specific T- and B-cell responses, as well as the production of anti-tTG IgA antibodies.

COMMENTS

Background

The origin of anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG) IgA in celiac disease has proven to be elusive and currently two theories exist. One theory is a hapten-carrier model, whereby gliadin-specific T cells provide help for tTG-specific B cells. The other is based on molecular mimicry between tTG and gliadin.

Research frontiers

The recent detection of antibodies in celiac patients specific for deamidated gliadin peptides (DGP), the product of tTG binding to gliadin peptides, provides an opportunity to address the correlation between the production of anti-tTG IgA and the antibodies against DGP in celiac patients.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This study has made the novel observation that the production of both IgG and IgA against DGP is significantly correlated with the production of anti-tTG IgA and weakly with anti-tTG IgG. This would indicate that the T and B cell response against DGP is fundamentally different from the T- and B-cell response against tTG, and would therefore support the hapten-carrier theory of the origin of tTG IgA.

Applications

By determining the origin of anti-tTG IgA in celiac disease, we obtain a better understanding of the (potentially pathogenic) role of anti-tTG IgA in the development of celiac disease.

Terminology

DGP and tTG are terms that refer to deamidated gliadin peptides and tissue transglutaminase, respectively. Also, gluten free diet (GFD) and GCD refer to gluten-free diet and gluten-containing diet.

Peer review

The data presented in this rapid communication are of interest to the celiac disease community. It is a rapid communication that examines the pattern of serum IgG and IgA levels specific to DGP and tTG in celiac disease patients. It also determines how the administration of a GFD therapy affects this pattern.

Supported by Grants from the National Institute of Health (#5R01DK057892-07 and #5R01DK071003-03) and Mayo Foundation

Peer reviewer: Atsushi Mizoguchi, Assistant Professor, Experimental Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, United States 617 726-8492, Simches 8234, 185 Cambridge Street, Boston, MA 02114, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Celiac sprue. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:180–188. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra010852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trier JS. Diagnosis of celiac sprue. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:211–216. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson RP. Coeliac disease. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34:239–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molberg O, Mcadam SN, Korner R, Quarsten H, Kristiansen C, Madsen L, Fugger L, Scott H, Noren O, Roepstorff P, et al. Tissue transglutaminase selectively modifies gliadin peptides that are recognized by gut-derived T cells in celiac disease. Nat Med. 1998;4:713–717. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotze LM, Utiyama SR, Nisihara RM, de Camargo VF, Ioshii SO. IgA class anti-endomysial and anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies in relation to duodenal mucosa changes in coeliac disease. Pathology. 2003;35:56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marietta EV, Camilleri MJ, Castro LA, Krause PK, Pittelkow MR, Murray JA. Transglutaminase autoantibodies in dermatitis herpetiformis and celiac sprue. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:332–335. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rashtak S, Ettore MW, Homburger HA, Murray JA. Comparative usefulness of deamidated gliadin antibodies in the diagnosis of celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:426–432; quiz 370. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sollid LM, Molberg O, McAdam S, Lundin KE. Autoantibodies in coeliac disease: tissue transglutaminase--guilt by association? Gut. 1997;41:851–852. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.6.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korponay-Szabo IR, Vecsei Z, Kiraly R, Dahlbom I, Chirdo F, Nemes E, Fesus L, Maki M. Deamidated gliadin peptides form epitopes that transglutaminase antibodies recognize. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:253–261. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31815ee555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu E, Li M, Emery L, Taki I, Barriga K, Tiberti C, Eisenbarth GS, Rewers MJ, Hoffenberg EJ. Natural history of antibodies to deamidated gliadin peptides and transglutaminase in early childhood celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:293–300. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31806c7b34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marsh MN. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity ('celiac sprue') Gastroenterology. 1992;102:330–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rostami K, Kerckhaert J, von Blomberg BM, Meijer JW, Wahab P, Mulder CJ. SAT and serology in adult coeliacs, seronegative coeliac disease seems a reality. Neth J Med. 1998;53:15–19. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(98)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laurin P, Wolving M, Falth-Magnusson K. Even small amounts of gluten cause relapse in children with celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;34:26–30. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baudon JJ, Chevalier J, Boccon-Gibod L, Le Bars MA, Johanet C, Cosnes J. Outcome of infants with celiac disease. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:1097–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(05)82173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shmerling DH, Franckx J. Childhood celiac disease: a long-term analysis of relapses in 91 patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;5:565–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghedira I, Sghiri R, Ayadi A, Sfar MT, Harbi A, Essoussi AS, Amri F, Korbi S, Jeddi M. [Anti-endomysium, anti-reticulin and anti-gliadin antibodies, value in the diagnosis of celiac disease in the child] Pathol Biol (Paris) 2001;49:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0369-8114(00)00010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simell S, Kupila A, Hoppu S, Hekkala A, Simell T, Stahlberg MR, Viander M, Hurme T, Knip M, Ilonen J, et al. Natural history of transglutaminase autoantibodies and mucosal changes in children carrying HLA-conferred celiac disease susceptibility. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1182–1191. doi: 10.1080/00365520510024034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mothes T. Deamidated gliadin peptides as targets for celiac disease-specific antibodies. Adv Clin Chem. 2007;44:35–63. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2423(07)44002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]