Abstract

Objective

Hemodynamic impairment in one hemisphere has been shown to trigger atypical ipsilateral motor activation in the opposite hemisphere on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). We hypothesized that reversing the hypoperfusion would normalize the motor activation pattern.

Methods

We studied 4 patients with high-grade stenosis and impaired VMR but no stroke. Change in fMRI motor activation pattern pre- and post-VMR normalization was compared with 7 healthy controls scanned at an interval of three months using voxel-wise statistical parametric maps and Region of Interest (ROI) analysis. fMRI was performed at 1.5T, 128×128 matrix, 19cm2FOV, slice-thickness= 4.5mm/0skip, TR=4000, slices=25, voxel dimensions 1.5×1.5×4.5mm.Subjects performed a repetitive hand closure task in synchrony with 1Hz metronome tone. We used repeated-measures ANOVA to compute the interaction between group (patients/controls) and time by obtaining the average BOLD-signal of 3 motor ROIs in each hemisphere.

Results

Two patients normalized their VMR after spontaneous resolution of dissection, and 2 following revascularization procedures. Both voxel-wise statistical maps and ROI analysis showed that VMR normalization was associated in each case with a reduction in the atypical activation in the hemisphere opposite to the previously hypoperfused hemisphere (p<.0001).

Interpretation

In the presence of a physiologic stressor such as hypoperfusion, the brain is capable of dynamic functional reorganization to the opposite hemisphere that is reversible when normal blood flow is restored. These findings are important to our understanding of the clinical consequences of hemodynamic failure and the role of the ipsilateral hemisphere in maintaining normal neurological function.

Introduction

The central nervous system has a unique ability to dynamically reorganize in response to pathological stressors such as stroke.1 It has been shown with functional imaging that whereas normal subjects generally activate contralateral motor cortex while performing a simple hand motor task, the same task after injury generates additional activity in the ipsilateral hemisphere,2 which then reduces over time.3, 4 We previously expanded the range of attributable cerebral triggers associated with emergence of ipsilateral motor activation, demonstrating the existence of ipsilateral task-related activation in patients with large-vessel disease and impaired vasomotor reactivity despite the absence of stroke5 or TIA.6 These findings suggested that a state of unilaterally impaired cerebral hemodynamics is sufficient to alter the motor activity pattern. A question that remained to be answered was whether a reversal of the hypoperfusion would result in normalization of the ipsilateral motor-related activity in the other hemisphere. A return to a canonical pattern would suggest that neurons in the hypoperfused heimisphere existed in a dysfunctional, but viable state, capable of regaining function if physiological conditions are restored. On the other hand, detecting no change in the ipsilateral activation would suggest that hemodynamic impairment induced a subclinical neuronal injury that disrupted irreversibly the primary circuits of the brain, resulting in a lasting recruitment of alternative brain regions to share the neuronal burden of normal neurological function. We investigated these 2 alternative possibilities by examining the brain activation patterns in patients with unilateral cerebral hemodynamic impairment whose hemodynamic failure subsequently reversed. We hypothesized that hemodynamic normalization, as measured by vasomotor reactivity (VMR) using Transcranial Doppler (TCD) with 5% CO2 inhalation, would reverse the increased motor-related functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) signal in the opposite hemisphere.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Four patients with large vessel disease, impaired VMR and no history of stroke or TIA were compared with 7 healthy controls. Patients were consecutively drawn from cerebrovascular patients evaluated by the neurovascular service who met eligibility criteria. Patient 1 was a 48 year old woman with a left carotid artery dissection. She had spontaneous recanalization 3 months later, with a concomitant normalization of VMR. Patient 2 was a 53 year old man with right middle cerebral artery (MCA) high grade stenosis who had spontaneous normalization of VMR when measured18 months later. Patient 3, a 58 yr old man, underwent stenting of a high grade left internal carotid (ICA) stenosis, restoring normal VMR at 3 months. Patient 4, a 78 year old man with right ICA high grade stenosis also underwent stenting that restored normal VMR as measured by TCD on his 3rd post-operative day. Normal VMR was still present 2 months later at the time the patient underwent a follow-up fMRI scan. Seven healthy controls, aged 58 ± 9 had normal neurological examination, no evidence for focal lesions on FLAIR or DWI MR images, and normal carotid and transcranial Doppler studies. All participants gave written informed consent for the study using an IRB-approved, HIPAA-compliant protocol. For additional clinical information, see Supplementary data.

Vasomotor Reactivity Measurement

To determine cerebral hemodynamic status, all patients underwent cerebral VMR testing. Bilateral TCD monitoring (Pioneer TC 4040; Nicolet Biomedical, Madison, WI, USA) of the MCAs was performed at an insonation depth of 50 to 56 mm as described previously.7 After 2 minutes of baseline measurement, subjects breathed 5% CO2 (carbigene) via facemask for 2 minutes. VMR was calculated as percent rise in ipsilateral MCA mean flow velocity (MFV) per mm Hg pCO2. The contralateral VMR was measured as a control, expected always to be in the normal range. 'Normal' VMR was defined as a rise in MCA MFV of at least 2.0%/mmHg pCO2, corresponding to 2 standard deviations below the mean of control data from a previous study.7

Imaging

During fMRI subjects performed a repetitive hand closure task in synchrony with 1Hz metronome click in three 20- second blocks alternating with rest. Imaging was performed on a GE 1.5T magnet, 128×128 matrix, 19cm2 FOV, slice thickness=4.5mm/0skip, TR=4000, TE=60, flip angle=60, 25 slices, functional voxel dimensions 1.5×1.5×4.5mm. Image volumes were co-registered, motion and slice timing-corrected, subjected to high pass filter, normalized to Talairach template, and smoothed with an 8mm Gaussian kernel. The first 3 volumes of each run were excluded for signal stabilization. For all patients, motion correction (3 transposition planes, 3 directions of rotation) was well within the functional voxel dimensions. VMR and fMRI measurements were performed on the same day.

Voxel-wise analysis

Images were flipped to make the “right” the hypoperfused hemisphere and the “left” the normally perfused hemisphere. Therefore the left hand, contralateral to the hypoperfused hemisphere, was designated as the “affected hand” and the right hand in patients and controls was designated as the “unaffected hand.”

A fixed-effects group analysis compared the blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) activity in the 4 patients at Time 1 (baseline) and Time 2 (after normalization of VMR) with the control groups’ BOLD activity at Time 1 and Time 2, evaluating for a group-by-time interaction. The interaction contrast was therefore represented as (P2−P1) − (C2−C1) where P1 and P2, C1 and C2 represented task-related fMRI data at Time 1 and Time 2, from patients and controls respectively (null hypothesis: P2−P1=C2−C1, i.e. no difference in change in activity over time between groups). We were particularly interested in change in the ipsilateral motor regions where previous studies had shown increased activity in response to hypoperfusion in the opposite hemisphere.5, 8 All contrasts were assessed at a threshold of t=3.0, corresponding to p=.0027 uncorrected, a common threshold for fMRI studies of this type. A formal statistical test using regions of interest (ROIs) was performed to confirm our findings (see below). In order to exclude the possibility that a group effect was driven by 1 or 2 patients, the Time 2 − Time 1 contrast was examined in each patient individually.

ROI Analysis

To quantitatively test our hypothesis that the atypical activation in the ipsilateral motor cortical areas decreased as a result of VMR normalization, we performed an independent ROI analysis among all subjects over 2 time points by computing average BOLD signal intensity (beta value: β) in the primary sensorimotor cortex (M1S1), lateral premotor cortex, and supplementary motor area (SMA). ROIs were drawn using each subject’s T1-structural MRI scan as a template to maximize the specificity of the ROIs, following the anatomical definition of these areas described by Fink and colleagues.9 ROI creation was blinded to the activation pattern to avoid bias. The β of the 3 ROIs in each hemisphere at each time point was averaged, then entered into a repeated-measures ANOVA to look for interaction between groups (patients vs. controls) and time. Two computations were performed – the laterality index (β contra − β ipsi) / (β contra + β ipsi) and absolute Beta value of the ipsilateral hemisphere alone.

Results

Voxel-Wise Statistical Parametric Map

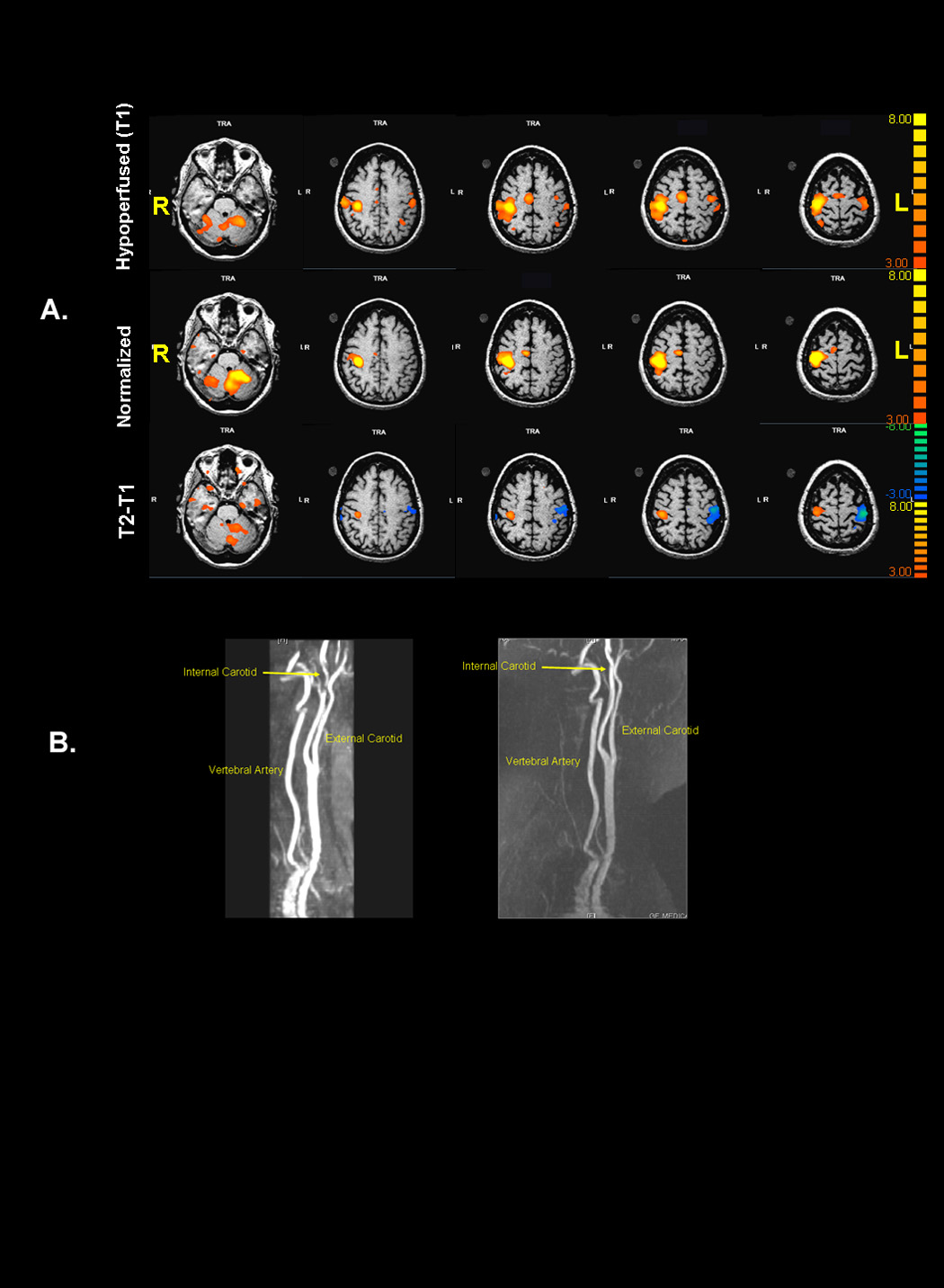

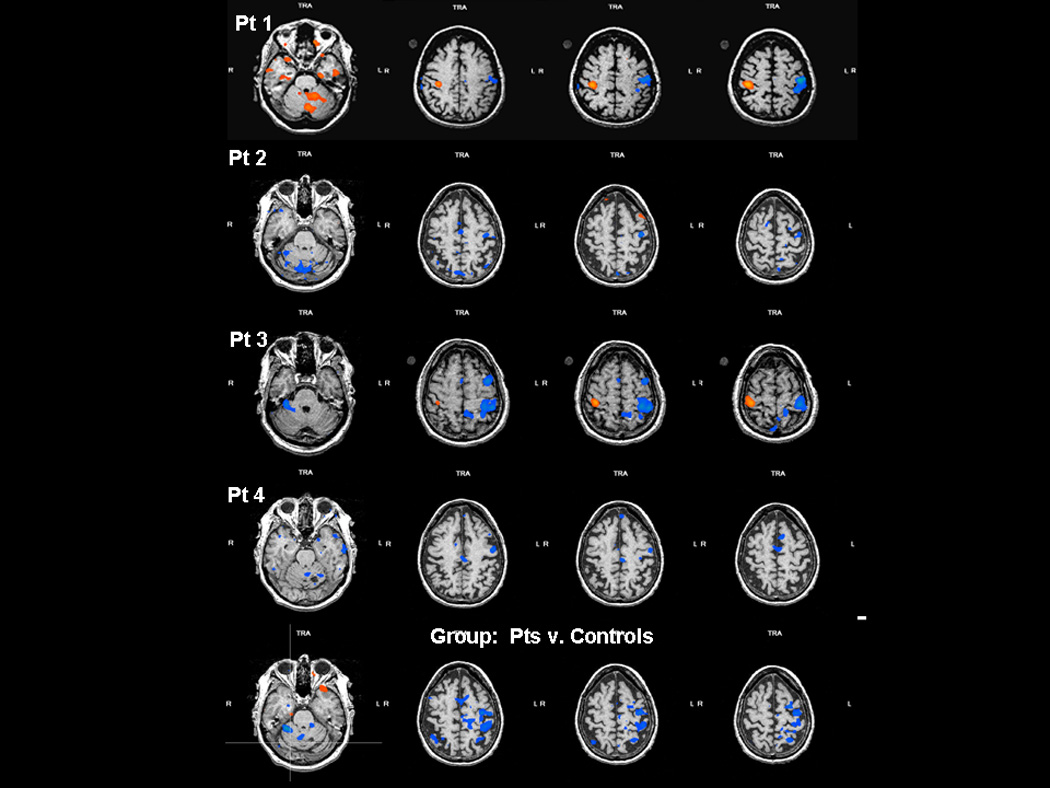

All patients and controls had normal neurological function at the time of testing. No mirror movements were detected visually during brain scans. As expected, control subject hand movement and the “unaffected hand” of patients was associated with activation predominantly in contralateral M1S1, premotor and SMA. In contrast, “affected hand “ movements in patients with impaired VMR activated additional motor areas in the ipsilateral hemisphere, confirming previous work.5, 8 Figure1(a) illustrates in patient 1 the decrease in BOLD signal associated with recanalization of her carotid dissection (Figure 1b) and consequent normalization of VMR. The T2−T1 contrast in each of the other 3 patients as well as group data comparing patients with controls produced similar results (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

ROI Analysis

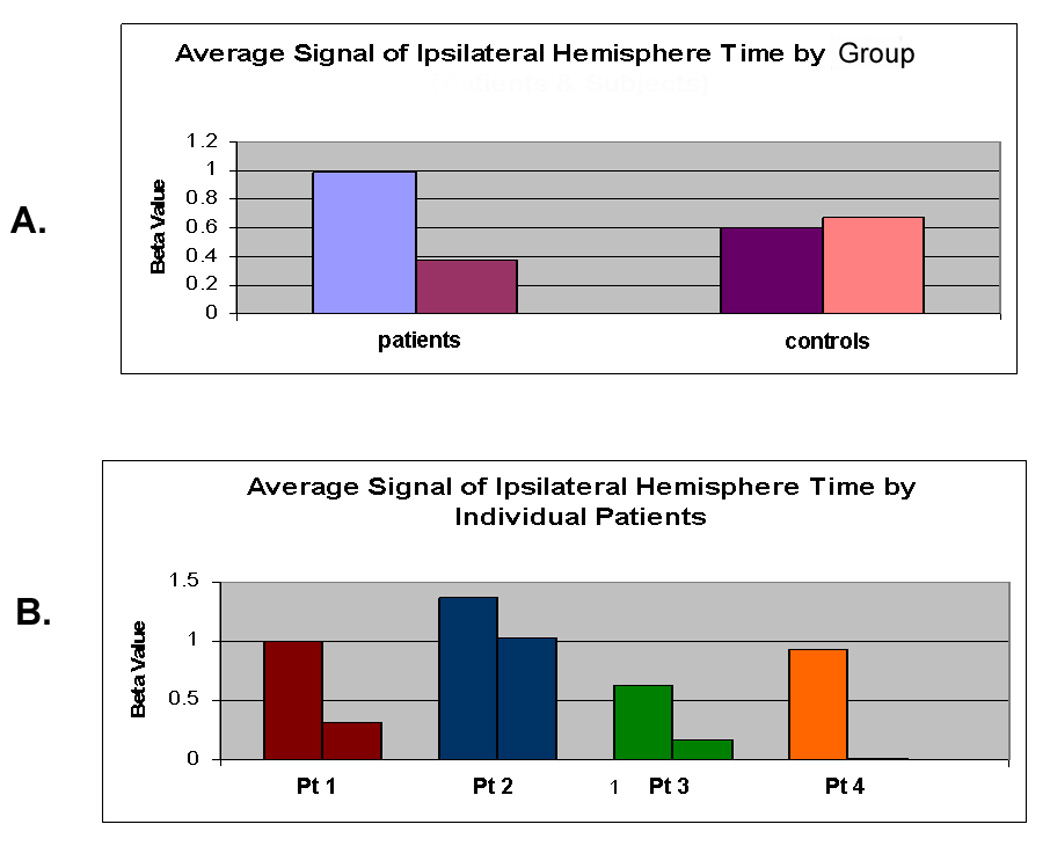

For the average BOLD signal in the 3 motor region ROIs, there was significant group × time interaction driven by an increase in laterality index in patients compared with controls, indicating a shift of activity towards the contralateral hemisphere (P<0.01; Figure 3a, Table 2 in supplementary information). We found a significant decrease in BOLD intensity in patients as compared to controls in the ipsilateral hemisphere after VMR normalization, confirming that the interaction was contributed significantly to by changes in the ipsilateral hemisphere. (P<0.001 and Table2). These findings were reproducible in each of the 4 patients (Figure 3b). Also consistent with our prior work, the BOLD activation in the 3 motor ROIs in the hypoperfused hemisphere at baseline was slightly but not significantly reduced compared with controls (1.37 vs. 2.46, p=0.06), suggesting that there was preserved neurovascular coupling despite the hemispheral hypoperfusion.

Figure 3.

Discussion

In this prospective, proof-of-principle study, we extend our previous findings of abnormal hemodynamics inducing ipsilateral motor activation6 by demonstrating that removal of the trigger of hemodynamic failure is associated with restoration of a typical, predominantly contralateral motor activation pattern. Our findings suggest that impaired VMR is not only sufficient to produce an alteration in motor networks, but is a reversible trigger as well.

The mechanism of the phenomenon we observed has yet to be determined. The presence of activity in the opposite hemisphere may be the result of cross-hemispheral disinhibition as has been demonstrated after experimental10 and clinical11 stroke. The return to a typical balance of contralateral-ipsilateral activity in response to revascularization suggests that neurons in the hypoperfused hemisphere may exist in a dysfunctional but viable state that can be reversed if physiological conditions are restored. Such a state has been difficult to demonstrate in humans, although reversal of cognitive dysfunction has been reported following restoration of normal cerebral hemodynamics with heart transplant,12 carotid endarterectomy,13 and extracranial-intracranial bypass.14 Evidence at both cellular and clinical levels for such a process comes from chronically ischemic myocardium which resumes function by restoring coronary blood flow.15–17

A similar state of reversible dysfunction has also been described in neurons in rats subjected to chronic ischemia. Neurons were shown to lower their energy needs when diminished energy substrates are accessible.18, 19 The likelihood that neurons would regain function with restoration of blood flow is thought to depend on the acuity of ischemia,20 duration of ischemia,17 volume of ischemia,21 and degree of hypoperfusion.19 With regard to our patients, it may be that the severity, duration, and volume of hypoperfusion were great enough in our patients to impair normal neuronal activity, but not great enough to cause irreversible damage. The relative acuity with which the presence of ipsilateral BOLD activation was identified in patient 1, 6 weeks after carotid dissection, suggests that the process may happen fairly quickly. Reorganization in experimental10 stroke has been shown to appear within minutes, clinically as early as 24 hours.3

An alternative explanation for our findings might be that the carotid occlusion caused a relative shunting of blood flow to the opposite hemisphere, resulting in higher BOLD signals there, and then when the vessel recanalized the blood flow was redistributed away from that side, resulting in a reduction in BOLD. This scenario is unlikely since a normally functioning hemisphere should have intact autoregulation, maintaining normal CBF regardless of whether the opposite hemisphere has a reduced flow. Furthermore, quantitative CBF measurements in carotid occlusion show no increased blood flow in the opposite hemisphere.22

Limitations of our study include a small sample size. Our group results reached statistical significance, however, and more importantly, results were demonstrated in each individual patient. Another concern is an alternative explanation for the change in laterality index in which a reduction BOLD activity in the hypoperfused hemisphere could be due to neurovascular uncoupling,23 which then could have been reversed when the hemisphere was reperfused. Although we found a mildly reduced BOLD signal in the hypoperfused hemisphere in our cohort, it is the presence of activity in the opposite hemisphere that constituted evidence for reorganization, and the demonstrated reduction in activation with revascularization that indicated its reversibility.

Finally, our results have important implications for understanding the role of the ipsilateral hemisphere in sustaining normal neurological function. An absence of a subtle motor dysfunction prior to revascularization could not be completely ruled out as we based our assessment of normality on the patients’ lack of symptoms and a normal neurological exam. Our study is unique in showing presence and reversal of increased ipsilateral activation in the absence of symptoms, in contrast to most studies of brain reorganization in cerebrovascular patients in which ipsilateral motor activation is associated with persistent neurological dysfunction.4, 24, 25 The idea of silent, brain reorganization has precedent in the neuroscience literature, both in describing neuroplasticity in the setting of chronic brain tumors26 and arteriovenous malformations,27 as well as in descriptions of unconscious skill learning in normal subjects.28 Further study is needed to elucidate the physiological mechanisms underlying the reversible recruitment of the ipsilateral hemisphere in the absence of a structural brain lesion or a symptomatic state.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Brandon Minzer for his technical assistance. Funded by NIH grant 5R01HD043249 and the Levine Research Fund.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial relationships or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Weiller C, Chollet F, Friston KJ, et al. Functional reorganization of the brain in recovery from striatocapsular infarction in man. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:463–472. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johansen-Berg H, Rushworth MF, Bogdanovic MD, et al. The role of ipsilateral premotor cortex in hand movement after stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14518–14523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222536799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall RS, Perera GM, Lazar RM, et al. Evolution of cortical activation during recovery from corticospinal tract infarction. Stroke. 2000;31:656–661. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward NS, Brown MM, Thompson AJ, Frackowiak RS. Neural correlates of motor recovery after stroke: a longitudinal fMRI study. Brain. 2003;126:2476–2496. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krakauer JW, Radoeva PD, Zarahn E, et al. Hypoperfusion without stroke alters motor activation in the opposite hemisphere. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:796–802. doi: 10.1002/ana.20286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall RS, Krakauer JW, Matejovsky T, et al. Hemodynamic impairment as a stimulus for functional brain reorganization. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1256–1262. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall RS, Rundek T, Sproule DM, et al. Monitoring of cerebral vasodilatory capacity with transcranial Doppler carbon dioxide inhalation in patients with severe carotid artery disease. Stroke. 2003;34:945–949. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000062351.66804.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall RS, Krakauer JW, Radoeva PD, et al. Hemispheric hemodynamic impairment in the absence of stroke induces fMRI activation in the opposite hemisphere. Neurology. 2004;62:A541. doi: 10.1002/ana.20286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fink GR, Frackowiak RS, Pietrzyk U, Passingham RE. Multiple nonprimary motor areas in the human cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:2164–2174. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.4.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strens LH, Fogelson N, Shanahan P, et al. The ipsilateral human motor cortex can functionally compensate for acute contralateral motor cortex dysfunction. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1201–1205. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00453-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerloff C, Bushara K, Sailer A, et al. Multimodal imaging of brain reorganization in motor areas of the contralesional hemisphere of well recovered patients after capsular stroke. Brain. 2006;129:791–808. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deshields TL, McDonough EM, Mannen RK, Miller LW. Psychological and cognitive status before and after heart transplantation. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:62S–69S. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(96)00078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fearn SJ, Hutchinson S, Riding G, et al. Carotid endarterectomy improves cognitive function in patients with exhausted cerebrovascular reserve. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;26:529–536. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(03)00384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sasoh M, Ogasawara K, Kuroda K, et al. Effects of EC-IC bypass surgery on cognitive impairment in patients with hemodynamic cerebral ischemia. Surg Neurol. 2003;59:455–460. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(03)00152-6. discussion 460-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braunwald E, Rutherford JD. Reversible ischemic left ventricular dysfunction: evidence for the "hibernating myocardium". J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1467–1470. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marban E. Myocardial stunning and hibernation. The physiology behind the colloquialisms. Circulation. 1991;83:681–688. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.2.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahimtoola SH. From coronary artery disease to heart failure: role of the hibernating myocardium. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:16E–22E. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80443-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de la Torre JC, Fortin T, Park GA, et al. Brain blood flow restoration 'rescues' chronically damaged rat CA1 neurons. Brain Res. 1993;623:6–15. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de la Torre JC, Saunders J, Fortin T, et al. Return of ATP/PCr and EEG after 75 min of global brain ischemia. Brain Res. 1991;542:71–76. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90999-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall RS, Lazar RM, Pile-Spellman J, et al. Recovery of brain function during induced cerebral hypoperfusion. Brain. 2001;124:1208–1217. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.6.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohta H, Nishikawa H, Kimura H, et al. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion by permanent internal carotid ligation produces learning impairment without brain damage in rats. Neuroscience. 1997;79:1039–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grubb RL, Jr, Derdeyn CP, Fritsch SM, et al. Importance of hemodynamic factors in the prognosis of symptomatic carotid occlusion. Jama. 1998;280:1055–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.12.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powers WJ, Fox PT, Raichle ME. The effect of carotid artery disease on the cerebrovascular response to physiologic stimulation. Neurology. 1988;38:1475–1478. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.9.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calautti C, Leroy F, Guincestre JY, et al. Sequential activation brain mapping after subcortical stroke: changes in hemispheric balance and recovery. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3883–3886. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feydy A, Carlier R, Roby-Brami A, et al. Longitudinal study of motor recovery after stroke: recruitment and focusing of brain activation. Stroke. 2002;33:1610–1617. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000017100.68294.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrovich NM, Holodny AI, Brennan CW, Gutin PH. Isolated translocation of Wernicke's area to the right hemisphere in a 62-year-man with a temporo-parietal glioma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:130–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazar RM, Marshall RS, Pile-Spellman J, et al. Anterior translocation of language in patients with left cerebral arteriovenous malformation. Neurology. 1997;49:802–808. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.3.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willingham DB, Salidis J, Gabrieli JD. Direct comparison of neural systems mediating conscious and unconscious skill learning. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1451–1460. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]