Abstract

Objective:

The prevalence of drug and alcohol use among patrons of clubs featuring electronic music dance events was determined by using biological assays at entrance and exit.

Method:

Using a portal methodology that randomly selects groups of patrons on arrival at clubs, oral assays for determining level and type of drug use and level of alcohol use were obtained anonymously. Patrons provided self-reported data on their personal characteristics. A total of 362 patrons were interviewed at entrance and provided oral assay data, and 277 provided data at both entrance and exit.

Results:

Overall, one quarter of all patrons surveyed at entrance were positive for some type of drug use. Based on our exit sample, one quarter of the sample was positive at exit. Individual drugs most prevalent at entrance or exit included cocaine, marijuana, and amphetamines/stimulants. Only the amphetamine/stimulant category increased significantly from entrance to exit. Drug-using patrons arrive at the club already using drugs; few patrons arrive with no drug use and leave with detectable levels of drug use. Clubs vary widely in drug-user prevalence at entrance and exit, suggesting that both events and club policies and practices may attract different types of patrons. Approximately one half of the total entrance sample arrived with detectable alcohol use, and nearly one fifth arrived with an estimated blood alcohol concentration of .08 or greater. Based on our exit sample data, one third of patrons were intoxicated, and slightly less than one fifth were using both drugs and alcohol at exit. Clubs attract a wide array of emerging adults, with both genders and all ethnicities well represented. Clubs also attract emerging adults who are not in college and who are working full time.

Conclusions:

At clubs featuring electronic music dance events, drug use and/or high levels of alcohol use were detected using biological assays from patrons at entrance and exit from the clubs. Thus, these clubs present a potentially important location for prevention strategies designed to reduce the risks associated with drug and alcohol use for young people. Combined substance use may prove particularly important for prevention efforts designed to increase safety at clubs. Personal characteristics do not identify drug users, suggesting that environmental strategies for club safety may offer more promise for promoting health and safety.

In the club setting, a popular form of entertainment for emerging adults (i.e., 18- to 25-year-olds) features electronic music and dance events (EMDEs). EMDEs share some similarities with rave events, featuring electronically produced music (i.e., not live performances), encouraging dancing (i.e., with sufficient floor space for dancing, music conducive to dancing), and attracting young emerging-adult patrons. EMDEs are located in business establishments such as bars and clubs that are licensed to sell alcohol. These business establishments provide environments that may attract emerging adults engaged in problem behavior.

A common perception persists that clubs sponsoring EMDEs encourage or support drug use. For example, public concerns regarding drug overdoses, noise, and other behaviors have generated local, state, and federal policies to control establishments that feature such events (Leinwand, 2002). Yet, relatively little research exists concerning actual drug use and problems in these environments. Unlike the rave scene that often occurred in various impromptu locations, making health promotion and prevention initiatives more difficult, the club scene provides a setting that is already subjected to various city, state, and federal regulations and oversight. Furthermore, these business establishments often are expected to control public behaviors while still maintaining a viable business.

The recognition of this tension between running a successful business and not promoting behaviors that could result in punitive restrictions on the club environment underscores the importance of knowing more about the prevalence and type of problems common to the EMDE scene. Our focus is on examining whether EMDEs attract drug users to the club and assessing the extent to which their drug use may present problems for the management of the establishment as well as to the health and safety of the patrons.

Different types of EMDEs may be hosted in the same physical club location on different nights of the week, and, in general, different types of music are featured on different days of the week and possibly even on the same evening. Themes for the events are often evident, and these themes may be designed to attract different clientele. For instance, some events are hosted to attract the gay/lesbian crowd. Other examples are events that feature gothic music, and events where the dress and appearance of the clientele reflect the specific theme for the night. Some events and clubs are more “upscale” and are clearly focused on clientele who can afford more expensive entertainment. Promoters, who perform a different role from the club manager or owner, stage the events in the club setting, contract with the disk jockeys to produce the night's music, advertise the event to attract patrons, and sometimes provide security for the events.

EMDEs attract young, emerging adults, and the characteristics of the patrons vary widely. No specific racial or ethnic groups are particularly more likely to attend (Miller et al., 2005). Both genders frequent the events, and both working young adults and students are found at these events. Among the studies that have been conducted, most research provides self-reports of prior drug use or intentions to use drugs at these type of events (Degenhardt et al., 2006), and little information exists based on independent drug-test methods. For example, in a small U.S. study (N = 96), Arria et al. (2002) reported that 89% of club attendees reported lifetime Ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA]) use, 49% reported using Ecstasy in the past 30 days, and 20% reported using Ecstasy within the previous 2 days. In addition, international studies have emphasized the prevalence of drug use at raves, which also feature dancing and electronic music. Among the participants (N = 293) at six raves in Switzerland, the most common self-reported drugs used in the preceding 30 days were cannabis (53.8%), MDMA/Ecstasy (22.7%), and cocaine (20.7%) (Chinet et al., 2007). Lifetime rates of self-reported drug use were higher, with reported rates as follows: cannabis = 68.8%; MDMA/Ecstasy = 40.4%; cocaine = 35.9%; amphetamines = 26.4%; hallucinogens = 35.6%; nitrous oxide = 24.4%; methamphetamines = 20.7%; GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate) = 18.8%; and acid/LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) = 22.4%. Barrett (2005) found a modest association (r = .259) between the number of reported rave events attended and the number of self-reported substances used at the most recent event. Actual biological samples are available for only one prior, small study conducted by the authors (Furr-Holden et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2005). In that study, which selected clubs that were considered high risk, half (45%) of the attendees were positive for drug use based on oral assay data (Miller et al., 2005). Further, driving and drug/alcohol use were identified as important risk factors in the sample (Furr-Holden et al., 2006).

Both prior studies and popular perceptions support the hypothesis that drug use is linked to attendance at EMDEs. Because most of the studies are based on self-reported drug use and the measurement varies across studies (e.g., lifetime use, last 30-day use, use during the evening), deriving any understanding of the connections between EMDEs and drug use is speculative at best. Furthermore, it is difficult to determine whether the drug use predominantly occurs on the premises or whether drug users attending the events used drugs before they arrived.

This article reports on the prevalence of drug and alcohol use among patrons of clubs that feature EMDEs by using the portal survey data collection approach (Voas et al., 2006). This methodology allowed us to collect biological assays of drug use as patrons entered and exited the premises. To our knowledge this was the first large-scale study of patrons attending EMDEs, located on both the East and the West Coasts of the United States, in which biological measures of substance use were used. By obtaining both entrance and exit data on drug use among patrons, we address the issue of whether patrons arrive at the club already under the influence or whether they arrive without having used drugs and use them exclusively within the club. In addition, we explore the types of drugs that comprise the current club drug scene for the clubs on the East and the West Coasts. Variation in prevalence of drug use across different events provides another focus of inquiry in this study. Finally, we examine the extent to which patron characteristics are associated with drug use in the club setting. Data for these analyses are based on a component of a larger National Institute on Drug Abuse–funded study, which had three components: (1) observational measures of club environments, (2) manager and promoter interviews, and (3) portal surveys. These data are based on the portal surveys.

Method

Sampling

A key sampling issue was to ensure that our study included clubs that would reflect a range of patron drug use from “high” to “low.” In the first component of the larger study, we conducted observations for 98 events randomly selected from events advertised on the Internet and in local newspapers for the East and the West Coasts. Our selection of clubs for the research described herein was based on data from that observational survey, which identified high- and low-risk locations for drug use across 51 clubs (Miller et al., submitted for publication). To ensure that the clubs included in this study represented the full range of “low” to “high” drug-risk settings, we generated an index of risk based on observed indicators (e.g., observed drug use at the club, drug-use conversations overheard, observer offered drugs).

Owners and managers were approached to seek permission to conduct the portal study at their respective clubs. We obtained permission to collect data from 12 different events at clubs in the San Francisco Bay and the Baltimore/Washington, D.C., areas. Each club hosts different events on different nights of the week, and we targeted conducting portal surveys at the same event used during the observational component of the study (Miller et al., submitted for publication). If the same event was no longer occurring at the club, however, we targeted whatever event was occurring on the same night of the week for which observations initially were conducted.

Once a club location and night of the week were selected, portal method surveys were used to collect data from patrons as they entered and exited the clubs. Portal survey data collection procedures included obtaining data from interviews, self-administered questionnaires, and oral-assay tests.

A random selection procedure was established to select potential participants for the portal. A fixed “line” was established for the recruiters, and club patrons were approached as they neared the entrance to the club. In most cases, patrons came from two directions, and there were two different recruitment points. The first person in a group whose feet crossed the line was approached, and all members of the group attending with this individual were invited to participate. The focus on feet rather than faces reduced the chances of unconscious biases affecting the selection process. If a group refused to participate, recruiters recorded the approximate age, gender, and race. Slightly more than half (56%) of the groups approached agreed to participate, which is similar to acceptance rates of other portal studies (e.g., Lange et al., 2006). Our decision to approach entire groups entering the club together (as opposed to individuals) was based on prior research conducted in portal settings that indicates a lower refusal rate when the entire group is allowed to participate rather than singling out an individual from the group (Voas et al., 2006). Participants were offered $5 at entrance and $10 at exit to answer survey/interview questions and to provide an anonymous oral fluid sample.

The team leader assigned to each participant an identification number that included a unique group number as well as individual number. This number was recorded on a wristband and on all data forms associated with the individual. The survey was anonymous. Informed consent statements were read to participants, and a copy of this information was offered. To maintain anonymity, no signatures were required. As patrons exited the club, study participants were invited to complete an exit survey and interview and to repeat the drug and alcohol tests. Their wristbands permitted us to connect entrance and exit data.

Personal characteristics were apparently similar between those who participated and those who refused to participate. The research team recorded observable characteristics of individuals who refused so as to allow the research team to document differences. Among the participants and those who refused to participate, there were similarities in the percent age of males and females, the percentage of non-Hispanic whites, and average group size. There was one significant difference between refusers and participants based on apparent demographics. Persons older in apparent age (36-55 years) were overrepresented among total refusals (20.7%) relative to participants (9.5%). Persons in this older age group, however, represented only 14.5% of total eligible respondents and thus do not necessarily represent a substantial bias in drug-use measurements. Although we could not tell via observation whether refusals were more likely to be drug users than participants, we are encouraged that younger attendees (our target audience) were not overrepresented among refusals.

At exit, recruiters looked for wristbands indicating that individuals were research participants and approached these individuals to determine whether they were interested in completing the second part of the research study. Many participants needed no prompting and walked directly to the research site. Exit interviews posed different logistical problems from entrance interviews, in that participants' entrances were staggered and their exits tended to converge around closing time.

Measures

Using the portal survey methodology, data from face-to-face interview questions, self-administered questionnaires, and oral assays were used for these analyses. All statistical tests of significance were conducted using generalized linear mixed model (PROC GLIMMIX in SAS [SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC]) that included participant group (the primary sampling unit) as a random variable.

Drug use.

Drugs were assayed from biological samples collected at both entrance and exit. Oral fluid samples were collected using the Quantisal collection unit (Immunalysis Corporation, Pomona, CA), and the oral fluid samples were tested in a controlled laboratory for the presence of drugs and alcohol upon entrance to the club at a later time. Substances assayed included the following major categories of drugs of interest in this study: (1) cocaine, including cocaine metabolites (benzoylecgonine [BZE]); (2) amphetamine and other stimulants (i.e., methamphetamine; 3,4-methylene-dioxy-N-ethylamphetamine [MDEA]; MDMA; 3,4-methyl-enedioxyamphetamine [MDA]); (3) marijuana/hashish (i.e., delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol [THC]); (4) phencyclidine (PCP); (5) opiates and other painkillers (i.e., 6-acetylmor-phine [a metabolite of heroin], hydrocodone [Vicodin and others], codeine, methadone [Dolophine, Methadose], hydro-morphone [Dilaudid], oxycodone [Oxycontin and others]); and (6) ketamine. GHB could not be detected through the oral fluid assays, and thus self-reports at entrance and exit were used for presence of GHB.

For all drugs tested with oral fluids, the presence of the drug was detected first in the screening test and then confirmed in a second test. Any confirmed presence in the oral fluids was considered a positive for drug use. From these results, respondents were classified as drug users or drug nonusers, and an overall index of the number of drug categories that were used in the clubs was created to reflect the following major categories of drugs: amphetamine, heroin/ morphine/major painkillers, and marijuana. The secondary test also provided the amount of the drug detected. Thus, increases and decreases in drug use over the evening could be determined.

Recent technological advances have increased the validity of using oral fluids for assessing drug use. Laboratory testing of oral fluids in comparison with blood (considered to be the gold standard) has increased the validity of using oral fluids for illicit-drug measurement. Garg (2008), in the most recent Handbook of Drug Monitoring Methods: Therapeutics and Drugs of Abuse, concludes, “Commonly abused drugs can only be detected 1-3 days after abuse using urine specimens. Oral-fluid analysis provides a convenient way of sample collection under direct supervision and is useful in assessing very recent drug use” (p. 337). This comment is confirmed via a review of the published toxicology research by Drummer (2006), who concludes that oral fluid has been used effectively in testing for illicit drugs. For example, oral fluid concentrations of amphetamines, cocaine, and some opioids are similar or higher than those in plasma, and oral-fluid concentrations of THC, the active ingredient in cannabis, are very similar to levels tested in blood. The validity and the reliability of using oral fluids to detect the presence of illicit drugs is based on recent use as confirmed by comparison with blood and/or urine by a number of studies (Laloup et al., 2005; Niedbala et al., 2001; Quintela et al., 2005; Samyn and van Haeren, 2000; Schepers et al., 2003; Toennes et al., 2005; Verstraete, 2004; Wylie et al., 2005).

Alcohol use.

The oral assays provided data on the presence of alcohol (ethanol) and the estimated blood alcohol concentration (BAC). Thus, increases and decreases in alcohol use over the evening could be determined.

Characteristics of participants.

Demographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, marital relationship status, student status, military status) were collected by interviewers during brief surveys at entrance and thus represent the self-reported status for all participants. Self-reported drug and alcohol use also were collected via self-administered survey instruments at both entrance and exit. These data were not included in these analyses, except for the use of GHB, which was available only through self-reports. However, no one who was negative on the drug-assay tests self-reported GHB use.

Results

Of the 371 patrons who agreed to participate in the study, oral-assay data were available for 362 patrons (98%). At exit, we were able to re-interview approximately three fourths of the participants (77%), and 98% of the patrons who were interviewed at exit agreed to complete an oral assay. Exit interviews were more difficult to obtain, because the patrons tended to leave en masse at closing hour. For the purposes of these analyses, complete data are available for 361 attendees at entrance and for 277 attendees at both entrance and exit.

Characteristics of the attendees

Participant characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The demographic composition of all participants who completed the entrance survey is quite comparable to that of participants who completed both entrance and exit surveys. Only the latter group is described here. Based on our working sample of 277 participants with both entrance and exit data, 41.3% of the participants were female, and about half (54.0%) were 25 years or younger. Almost three fourths (71.8%) were employed full time, and approximately one third (35.9%) were students. Approximately half of the sample (51.8%) was in a relationship, and half was not. Few of the participants (13.1%) were married (not shown in Table 1). The following racial/ethnic breakdown was reported: black/African American (21.8%), white (non-Hispanic) (48.7%), Hispanic (13.1%), Asian (6.5%), other race (4.0%), and more than one race/ethnicity (5.8%). A total of 161 groups were represented in this study, with the average (SD) number of attendees in a group being 2.07 (1.11). One fifth of the sample (18.4%) arrived at the club alone.

Table 1.

Patron characteristics

| Characteristic | Entire sample (N = 371) % | Entrance and exit sample (n = 277) % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 61.7 | 58.7 |

| Female | 38.3 | 41.3 |

| Age, in years | ||

| 18-25 | 48.5 | 54.0 |

| 26-35 | 42.0 | 37.3 |

| 36-55 | 9.5 | 8.7 |

| Employment status | ||

| Full time | 74.0 | 71.8 |

| Part time | 14.4 | 14.7 |

| Unemployed | 11.6 | 13.6 |

| Student status | ||

| Nonstudent | 66.4 | 64.1 |

| Student | 33.6 | 35.9 |

| Relationship status | ||

| In a relationship | 50.5 | 51.8 |

| Not in a relationship | 49.5 | 48.2 |

| Race | ||

| Black | 20.2 | 21.8 |

| White | 49.3 | 48.7 |

| Hispanic | 13.6 | 13.1 |

| Asian | 7.1 | 6.5 |

| Other | 4.4 | 4.0 |

| More than one race | 5.4 | 5.8 |

| Arrived alone | ||

| Yes | 20.5 | 18.4 |

| No | 79.5 | 81.6 |

Prevalence of drug use at entrance and exit

As indicated in Table 2, approximately one quarter of all attendees was drug-positive at entrance and exit. Drug use at entrance did not differ meaningfully when comparing all participants at entrance versus participants with both entrance and exit data (24.4% vs 20.9%).

Table 2.

Presence of drug and alcohol use at entrance and exita

| Drug | Entranceb (n = 361) % | Entrancec (n = 277) % | Exitd (n = 277) % |

| Cocaine | 12.2 | 8.3 | 11.2 |

| Amphetamines and stimulants | 6.9 | 6.5 | 11.2 |

| Methamphetamine | 2.8 | 2.5 | 4.3 |

| Ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA]) | 5.5 | 5.1 | 9.0 |

| Amphetamine | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) | 1.7 | 1.8 | 4.0 |

| 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-ethylamphetamine (MDEA) | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0 |

| Marijuana/hashish | 12.7 | 11.9 | 11.6 |

| PCP (phencyclidine) | 0.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Painkillers | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Codeine | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Oxycodone | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Hydrocodone | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate; liquid ecstasy/G), self-report only | 0 | 0 | 0.7 |

| Ketamine (K, special K) | 0 | 0 | 0.4 |

| Fluoxetine | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0 |

| Sertaline | 0.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Any drugs | 24.4 | 20.9 | 26.0 |

All data are based on oral assay except for GHB, for which no oral assay test is available and only self-report is used. Substances that were tested for but had no positive results were removed from above table: methadone, 6-acetylmorphine (metabolite of heroin), and hydromorphone;

entrance survey data regardless of whether participants completed the exit survey;

entrance survey data only for participants that also completed the exit survey;

exit survey data.

The following details on drug use on entrance and exit are based on participants with both entrance and exit data. Marijuana and cocaine were the most prevalent drugs detected at entrance (11.9% and 8.3%), followed by amphetamines/stimulants (6.5%). Comparing entrance levels with exit levels, the percentage of marijuana users found at the events remained constant (11.9% at entrance, 11.6% at exit). Neither did the percentage of cocaine users differ significantly from entrance to exit (8.3% to 11.2%, p = .19). The only significant increase between entrance and exit was for amphetamines and other stimulants. At entrance, 6.5% of the participants were detected to have amphetamines and other stimulants in their systems, and upon exit, this proportion nearly doubled (11.2%; F = 5.5, 1/392 df, p < .05). Of the 13 persons who converted from no amphetamine use at entrance to positive amphetamine use upon exit, four (30.8%) did test positive for other drugs (cocaine or marijuana) at entrance. There was little self-report use of GHB at the events: Only 1% reported use at exit only, and all of these individuals used other drugs that were detected in the bioassay tests.

Alcohol use and intoxication prevalence at entrance and exit

As shown in Table 3, there is little evidence that the total entrance sample differs from the sample with entrance and exit data in their use of alcohol or alcohol and drugs at entrance. Reporting on the levels of alcohol use and combined alcohol/drug use for the sample with both entrance and exit data, the following comparisons for entrance and exit data can be made. Almost half of the sample (43.0%) arrived at the club with detectable alcohol use, and 16.2% arrived with an estimated BAC of .08 or greater. At exit, 62.3% had detectable levels of alcohol, and almost one third (32.6%) of the sample was intoxicated. Statistically significant increases from entrance to exit were noted for both the presence of alcohol (F = 22.8, 1/392 df, p < .01) and the prevalence of intoxication (F = 20.7, 1/392 df, p < .01). A total of 45.1% of the sample entered with no detectable level of drugs or alcohol, but at exit, this percentage had decreased significantly to 27.2% (F = 19.5, 1/390 df, p < .01). Given that one of the main features of the club is access to alcohol, these figures are not surprising.

Table 3.

Level of alcohol use and drug and alcohol use at entrance and exit

| Variable | Entrance data: All entrance (n = 361) % | Entrance data: Entrance and exit only (n = 277) % | Exit data: Entrance and exit only (n = 277) % |

| Alcohol | |||

| No alcohol | 56.0 | 57.0 | 38.7 |

| Some (BAC < .08) | 25.5 | 26.7 | 29.7 |

| Intoxicated (BAC ≥ .08) | 18.6 | 16.2 | 32.6 |

| Drugs and alcohol | |||

| Neither drugs nor alcohol | 42.1 | 45.1 | 27.2 |

| Either drugs or alcohol | 47.4 | 45.8 | 58.1 |

| Both | 10.5 | 9.0 | 14.7 |

| Drugs and intoxicated (BAC ≥ .08) | 3.3 | 2.9 | 7.2 |

Note: BAC = blood alcohol concentration.

A safety concern is more evident, however, among those who combined the substances. At entrance, 9.0% of the sample arrived with both alcohol and drugs present, and this prevalence rate increased to 14.7% at exit, which represented a statistically significant (F = 3.9, 1/392 df, p < .05) increase in the combined use of alcohol and drugs at exit. A still greater public safety concern are those participants who had estimated BACs of .08 or greater and who used drugs. Although only 2.9% entered both intoxicated and using drugs, that rate increased to 7.2% at exit (F = 4.0, 1/392 df, p < .05). Yet, intoxication rates were not statistically different for those who tested positive for drug use versus those who were drug free at either entrance or exit (not shown in Table 3). At entrance, drug users and drug nonusers were intoxicated at the prevalence rates of 13.8% versus 16.9%, respectively (p = .54). At exit, intoxication rates were predictably higher than upon entry but still comparable between those who did not test positive for drugs and those who did (34.6% vs 25.0%, p = .15).

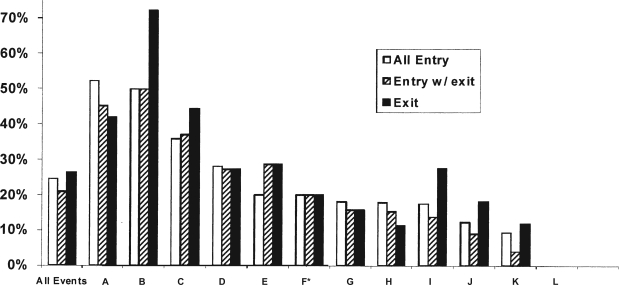

Variation in drug prevalence rates across events

Based on the entire entrance sample, there is wide variation in the percentage of patrons who tested positive for drug use across all events (Figure 1). Using the sample with both entrance and exit data, the percentage of participants who tested positive for drugs varied widely across events for both entrance and exit (see Figure 1). In two events (Events A and B), close to half of all participants tested positive for drugs at entrance. In one of these same events (Event B), nearly three fourths tested positive at exit. In contrast, there was one event where no one tested positive at entrance or exit (Event L). Despite the variation in prevalence rates, the vast majority of clubs hosted events where drug users were present at rates higher than one might expect among the general population in public places. Separating the 12 events into high and low drug-use groups (based on a median split), the high group had average entrance and exit rates of drug use among participants of 38.2% and 42.7%, respectively, as compared with 9.6% and 15.0%, respectively, for the low group. Across events, there was relatively little variation between the prevalence of drug use at entrance and exit except for a few events.

Figure 1.

Positive drug tests for all events at entrance and exit

Patron characteristics related to drug use

To provide a better understanding of whether certain patron characteristics are more associated with drug-use patterns, we examined sociodemographics comparing the prevalence of testing positive for drugs between different categories of participant characteristics. We conducted a series of analyses (using generalized linear mixed modeling) to predict drug use (whether measured at entrance or at exit) from participant demographic characteristics (gender, race/ethnicity, age category, student status, worker status, and relationship status).

These analyses do not support any personal characteristics as related to drug use, with one exception. There was no difference in the likelihood of testing positive for drugs between men and women (p = .16) or as a function of race (black vs white vs other; p = .41). Although trends suggested that the positive-drug-test results increased with age (18-25 vs 26-35 vs 36-55), the pattern was not statistically significant (p = .11). Similarly, neither student status (student vs nonstudent) nor marital status (commitment relationship vs dating vs no relationship) predicted drug use. Worker status, however, did predict drug use (F = 4.84, 1/141 df, p < .05; odds ratio = 2.15). This one lone statistically significant difference indicated that the estimated proportion of participants working full time who tested positive for drugs (.33) was higher than that for part-time/unemployed participants (.19).

Discussion

Among club patrons who use drugs, drug use occurs before entering the club for most patrons. Although there are exceptions to this pattern, clubs appear to be attracting drug users, and few clubs appear to have increases in the percentage of drug users during the course of the evening. The three most common types of drugs found in the oral assays at entrance among drug users were cocaine, marijuana, and amphetamines/stimulants. Among attendees from whom we had both entrance and exit data, significant increases were noted for amphetamine/stimulant use. These drugs are perceived as positive contributions to the experience by some club attendees, because increased alertness and activity potentially permit participants to stay longer at the club. The percentage of drug users who were intoxicated nearly doubled from entrance to exit. This combined use of alcohol and drugs poses health and safety concerns for the patrons and liability and management concerns for the club owners. Levels of physical impairment that are associated with this combined use of substances are an issue of potential legal liability to the club management if patrons who are using drugs have an adverse reaction to a combination of drug use and heavy alcohol consumption. As patrons leave the club under the influence of drugs and alcohol, issues of driving impairment and safety also are a concern.

Clubs that feature EMDEs provide a setting where emerging adults seek entertainment. These data indicate that the diversity of patrons who frequent the clubs presents an opportunity for developing interventions for emerging adults. Of specific importance is the fact that the clubs attract emerging adults who are in the work force and for whom college-based prevention programs would be inaccessible. Thus EMDEs are target sites for prevention of drug use and associated harm. The recognition, however, that drug users patronize club settings that feature EMDEs should not be construed to mean that these sites “cause” patrons to use drugs. In fact, the percentage of persons who are using drugs at entrance and exit remained fairly constant. Only 5% of the patrons arrived with no drug use and left the clubs with detectable drug use.

Another finding from this study is that there are great differences in drug-use levels across events, both at entrance and at exit. There are events that seem to disproportionately attract drug users. Owners and managers may benefit indirectly from drug use if drug users seek an environment that enhances the desired drug effects. However, owners and managers who discover that drug-using patrons are attracted to their events may be amenable to environmental prevention efforts for a variety of reasons. First, a disproportionate number of drug users at the clubs may pose higher risks for official sanctions from police or city regulators and may draw more neighborhood complaints. Second, owners and managers who are concerned about a legitimate business venture do not make money from selling drugs. Thus, this type of behavior is not profitable to the clubs, except in an indirect manner. Third, drug users may pose liability concerns. If bartenders and servers continue to serve drug-impaired individuals, the interactions between the alcohol and drugs may create health risks that are less predictable and easily detectable by staff trained to focus on alcohol problems. Fourth, safety issues that arise within the club scene because of drug use place a damper on the “fun environment” that is an important part of the club image.

Patron characteristics were limited in this study to keep the self-report data collection brief and to minimize questions that might be considered more intrusive and personal, such as sexual identification. Perhaps as a result of this limited personal information, patron characteristics that were collected for this study were not especially valuable as a tool to help clubs discourage drug use in clubs. Although only one characteristic (employed full time) distinguished drug users from drug nonusers, other unmeasured characteristics need to be considered in future studies. The lack of easily identifiable characteristics of drug users underscores the difficulty for owners and managers to prevent drug users from entering the club. Once individuals are within the club, more vigilance on behaviors within the club may be helpful. It may be an unfair burden on club owners and managers, however, to screen and prevent individuals from entering the club in the absence of any real data or information to guide these efforts.

These findings are limited by the small number of events (N = 12) from which well above 300 patrons were recruited. A broader range of events and a greater diversity of settings would provide a better understanding of drug use, patron characteristics, and the types of environmental indicators most associated with drug and alcohol use. Observational data on risk factors were initially used to identify clubs for this study on bio-assay measures of drug and alcohol use. The next step in our analysis plan is to test the association between observed risk factors, the club environment, and the level of drug and alcohol use. In addition, initial comparisons of self-reports with bioassay data from patrons suggest that bioassay measurements are important for accurate data collection on drug use. Further future research should determine if self-reports and bioassays are different for all types of drug users or only drug users who engage in specific types of drug use.

These findings have added importance, because there has been no published research concerning effective prevention strategies to reduce drug use, drug sales, or associated problems in club settings that feature EMDEs. The level of drug use (both before and within dance venues) and the risks associated with drug use—including drugged driving, violence, and sexual risk—support the need for prevention interventions at these settings. The potential of environmental strategies for reducing drug use and related harms is feasible for a number of reasons. Club owners and managers have the same motivation for restricting drug use and other risky behaviors on the premises, because such occurrences are not profitable for business. Concerns about licensures and revocations are relevant, should drug use become prevalent within the club. Legal difficulties also may be experienced if a club becomes known as a “hot spot” for drug activity. Legal liabilities are present as well: Club owners and managers become responsible for handling attendees who overdose while on the premises. As club owners and managers reported to us, drug users are not good for business, because they are not buying the primary product the club has to offer—alcohol. Clubs that become known as drug premises can keep more desirable patrons from frequenting the club. Despite these negative consequences of allowing drug users to frequent the club environment, owners and managers also are cognizant that the way drug issues are approached by the club is essential to their business. The overall image that the club needs to maintain is one that is attractive to the emerging adults with disposable income. Overly restrictive and controlling policies can result in losing the customer base. Together, these concerns provide a powerful motivator for club owners and managers to pursue environmental strategies that will keep behaviors in check without appearing overly restrictive.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01 DA018770, 2005-2008, awarded to Brenda A. Miller, principal investigator.

References

- Arria AM, Yacoubian GS, Jr., Fost E, Wish ED. Ecstasy use among club rave attendees. Arch. Pediat. Adolesc. Med. 2002;156:295–296. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett SP, Gross SR, Garand I, Pihl RO. Patterns of simultaneous polysubstance use in Canadian rave attendees. Subst. Use Misuse. 2005;40:1525–1537. doi: 10.1081/JA-200066866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinet L, Stephan P, Zobel F, Halfon O. Party drug use in techno nights: A field survey among French-speaking Swiss attendees. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2007;86:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Dillon P, Duff C, Ross J. Driving, drug use behaviour and risk perceptions of nightclub attendees in Victoria. Australia. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2006;17:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Drummer OH. Drug testing in oral fluid. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2006;27:147–159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furr-Holden D, Voas RB, Kelley-Baker T, Miller B. Drug and alcohol-impaired driving among electronic music dance event attendees. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;85:83–86. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg U. Hair, oral fluid, sweat, and meconium testing for drugs of abuse: Advantages and pitfalls. In: Dasgupta A, editor. Handbook of Drug Monitoring Methods: Therapeutics and Drugs of Abuse. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2008. pp. 337–364. [Google Scholar]

- Laloup M, Tilman G, Maes V, De Boeck G, Wallemacq P, Ramaekers J, Samyn N. Validation of an ELISA-based screening assay for the detection of amphetamine, MDMA and MDA in blood and oral fluid. Forensic Sci. Int. 2005;153:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange JE, Johnson MB, Reed MB. Drivers within natural drinking groups: An exploration of role selection, motivation, and group influence on driver sobriety. Amer. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:261–274. doi: 10.1080/00952990500479597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinwand D. Cities crack down on raves. USA Today. 2002. pp. 1–2. November 13. [Google Scholar]

- Miller BA, Furr-Holden CD, Voas RB, Bright K. Emerging adults' substance use and risky behaviors in club settings. J. Drug Issues. 2005;35:357–378. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, BA, Furr-Holden, D, Voas, RA, Johnson, M, Holder, HD, and Keagy, C. Drug use and risky behaviors in clubs: Observational indicators, submitted for publication

- Niedbala RS, Kardos KW, Fritch DF, Kardos S, Fries T, Waga J, Robb J, Cone EJ. Detection of marijuana use by oral fluid and urine analysis following single-dose administration of smoked and oral marijuana. J. Analyt. Toxicol. 2001;25:289–303. doi: 10.1093/jat/25.5.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintela O, Cruz A, de Castro A, Concheiro M, López-Rivadulla M. Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry for the determination of nine selected benzodiazepines in human plasma and oral fluid. J. Chromatogr. B: Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2005;825:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samyn N, van Haeren C. On-site testing of saliva and sweat with drugwipe and determination of concentrations of drugs of abuse in saliva, plasma and urine of suspected users. Int. J. Legal Med. 2000;113:150–154. doi: 10.1007/s004140050287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepers RJ, Oyler JM, Joseph RE, Jr., Cone EJ, Moolchan ET, Huestis MA. Methamphetamine and amphetamine pharmacokinetics in oral fluid and plasma after controlled oral methamphetamine administration to human volunteers. Clin. Chem. 2003;49:121–132. doi: 10.1373/49.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toennes SW, Kauert GF, Steinmeyer S, Moeller MR. Driving under the influence of drugs—evaluation of analytical data of drugs in oral fluid, serum and urine, and correlation with impairment symptoms. Forensic Sci. Int. 2005;152:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstraete AG. Detection times of drugs of abuse in blood, urine, and oral fluid. Therapeut Drug Monit. 2004;26:200–205. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200404000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Furr-Holden D, Lauer E, Bright K, Johnson MB, Miller B. Portal surveys of time-out drinking locations: A tool for studying binge drinking and AOD use. Eval. Rev. 2006;30:44–65. doi: 10.1177/0193841X05277285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie FM, Torrance H, Anderson RA, Oliver JS. Drugs in oral fluid: Part I. Validation of an analytical procedure for licit and illicit drugs in oral fluid. Forensic Sci. Int. 2005;150:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]