Abstract

Background: The frequencies and types of anal symptoms were compared with the frequencies and types of benign anal diseases (BAD).

Methods: Patients transferred from GPs, physicians or gynaecologists for anal and/or abdominal complaints/signs were enrolled and asked to complete a questionnaire about their symptoms. Proctologic assessment was performed in the knee-chest position. Definitions of BAD were tested in a two year pilot study. Findings were entered into a PC immediately after the assessment of each individual.

Results: Eight hundred seven individuals, 539 (66.8%) with and 268 without BAD were analysed. Almost one third (31.2%) of patients with BAD had more than one BAD. Concomitant anal findings such as skin tags were more frequently seen in patients with than without BAD (<0.01). After haemorrhoids (401 patients), pruritus ani (317 patients) was the second most frequently found BAD. The distribution of stages in 317 pruritus ani patients was: mild (91), moderate (178), severe (29), and chronic (19). Anal symptoms in patients with BAD included: bleeding (58.6%), itch (53.7%), pain (33.7%), burning (32.9%), and soreness (26.6%). Anal lesions could be predicted according to patients' answers in the questionnaire: haemorrhoids by anal bleeding (p=0.032), weeping (p=0.017), and non-existence of anal pain (p=0.005); anal fissures by anal pain (p=0.001) and anal bleeding (p=0.006); pruritus ani by anal pain (p=0.001), itching (p=0.001), and soreness (p=0.006).

Conclusions: The knee-chest position may allow for the accumulation of more detailed information about BAD than the left lateral Sims' position, thus enabling physicians to make more reliable anal diagnoses and provide better differentiated therapies.

Keywords: haemorrhoids, pruritus ani, fissure-in-ano, thrombosed external haemorrhoid, benign anorectal diseases, Sims' position, knee-chest-position

Introduction

Patients suffering from any symptoms related to the anus frequently and often incorrectly assume that their symptoms are due to haemorrhoids 1,2,3,4. Lockhart-Mummery once wrote "nearly every lesion around the anus is liable to be called 'piles' by the patient and not infrequently by the referring doctor also" 5. This practice still prevails: "Almost everyone suffers from haemorrhoids at some time in their lives" 6. "Haemorrhoids and their symptoms are one of the most common afflictions in the western world" 7.

The exact incidence of haemorrhoids is unknown as estimates vary 1,6,8,9. In the US about 1.5 million prescriptions for anorectal preparations are written yearly 10. The cost of treating benign anal diseases (BAD) in the United States exceeds 2 billion dollars annually 11.The German National Insurance Fund spends 38 million Euros yearly for ointments and suppositories whose use is not supported by any scientific data 12.

History taking does not lead to accurate anal diagnoses 1,13. It is also unknown which examination position (i.e. left-lateral, knee-chest, lithotomy or the upright standing-bented) is the most reliable for determining the causes of anal bleeding, anal itch, anal pain or anal burning. The sensitivity, specificity and predictive value of patients' positioning in diagnosis of BAD, concomitant anal findings (CAF), and multiple anal lesions (MAL) with one individual also remain unknown 3,14,15. We investigated the types and frequencies of anal complaints with respect to anal findings at proctologic assessment using the knee-chest position in contrast to the widely used left lateral Sims' position to evaluate its pros and cons.

Methods

Participants

Individuals were asked to complete a questionnaire that described their symptoms and signs (table 1). Proctologic assessment was performed in the knee-chest position 14 by inspection of the anal verge followed by digital examination of the anal canal, and anoscopy. Colono-, sigmoido- or rectoscopy were performed if necessary.

Table 1.

Patients' questionnaire with given answers

| 1. | Which symptom, sign or cause prompted you to seek help in our outpatient clinic? (Mark as many items as apply) |

| anal bleeding - in toilet paper, faeces or lavatory | |

| anal itch | |

| anal pain or discomfort | |

| anal burning (baking) | |

| anal soreness | |

| anal lump | |

| faecal soiling | |

| anal weeping | |

| anal mucous | |

| anal incontinence | |

| dubious abdominal pain | |

| constipation | |

| diarrhoea | |

| faecal occult blood test (FOBT) | |

| dubious anaemia | |

| screening colonoscopy | |

| elevation of tumour markers | |

| 2. | How long have you suffered from these symptoms or signs? |

| up to one week | |

| two to four weeks | |

| two to twelve months | |

| I do not have any signs or symptoms | |

| 3. | Did you treat yourself or seek help from a doctor? |

| I treated myself without the help of a doctor | |

| At first I treated myself then I looked for help from a doctor | |

| I immediately looked for help from a doctor |

Definitions

We used published definitions for BAD such as haemorrhoids (table 2) and pruritus ani (table 3). Concomitant anal findings (CAF) such as skin tags were defined as anal verge anatomical findings of unknown importance for BAD (table 4). Multiple anal lesions (MAL) were defined as more than one BAD found in one individual e.g. a fissure-in-ano with pruritus ani 14,15. Definitions were tested in a two year pilot study, and adopted into routine use ten months before start of the study. Findings were entered into a personal computer immediately after proctologic assessment of each individual.

Table 2.

Definitions of benign anal diseases (BAD)

| Anal lesion [Reference] | Definition, Illustration |

|---|---|

| Haemorrhoids 13 | "Haemorrhoids (or piles) are displaced anal cushions. Haemorrhoids should not be diagnosed unless prolaps or bleeding is a dominant symptom, in conjunction with visible distended or displaced anal cushions on anoscopy." (figure 1) |

| Fissure-in-ano 16 | "A fissure is a split in the lower half of the anal canal extending from the anal verge toward the dental line." (figures 2 and 3) |

| Thrombosed external haemorrhoid 13 | "Localised thrombosis which may affect the external plexus". (figure 4) |

Table 3.

Definition of four stages of pruritus ani according to Mazier1, Nagle10, Brossy17, Gayle18, Granet19, Mentha20, Fazio21, Tucker22, and Smith23.

| Grading | Terms, Definitions, Illustrations |

|---|---|

| mild | stage 1 No lesion seen at inspection of anal verge but the patient finds palpation and/or anoscopy painful, and other anal lesions have been excluded (figure 5). |

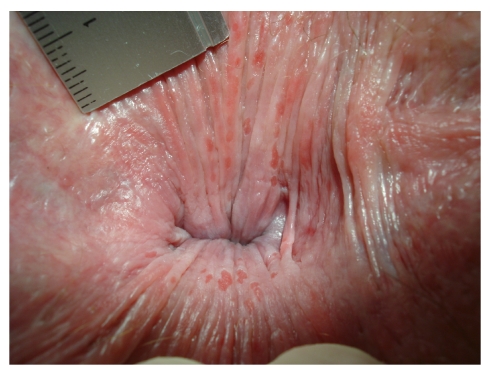

| moderate | stage 2 Red dry skin only (figure 6), at times weeping skin with superficial round splits and longitudinal superficial fissures. (figure 7). |

| severe | stage 3 Reddened, weeping skin, with superficial ulcers and excoriations disrupted by pale, whitish areas with no more hairs (figures 8 and 9). |

| chronic | stage 4 pale, whitened, thickened, dry, leathery, scaly skin with no hairs and no superficial ulcers or excoriations (figures 10 and 11). |

Table 4.

Definition of concomitant anal findings (CAF) found at inspection of anal verge during proctologic assessment

| Concomitant anal findings (CAF): Terms [References] | Definitions / Illustrations |

|---|---|

| Skin tags13 | "Skin tags are hypertrophied redundant folds of perianal skin" (figures 1,4,9,11). |

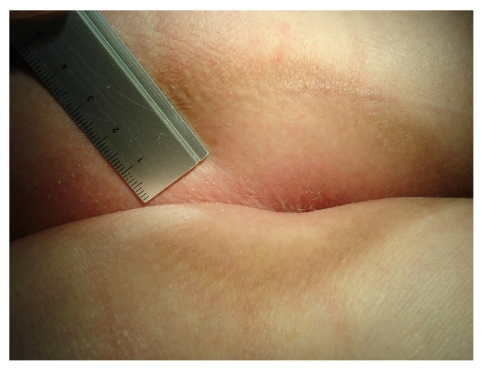

| Funnel shaped anus24 | "The buttocks are permanent in touch with each other and have to be parted firmly to be able to inspect the anal verge" (figures 12 and 13). |

| Hairy anus24 | "Hairs spread out almost carpet like to the anal verge" (figures 6 and 14). |

Statistics

Means +/- standard deviation were computed for continuous variables such as age. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical data such as the male to female ratio, history of symptoms, and anal lesions. Bivariate analyses were performed by using t-tests to compare independent groups and point-biserial correlations coefficients to analyse relationships between continuous and dichotomous variables. Bivariate relationships between pairs of dichotomous variables were analysed with Fisher's exact test. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to predict anal lesions based on answers of the patient questionnaire. Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (SPSS, Chicago, Il) version 15.

Results

A total of 876 individuals of both genders aged 16 - 80 years old who consecutively entered our office from July 25, 2005 until December 20, 2005 were enrolled. They were referred by general practitioners, physicians or gynaecologists in order to determine the causes of anal and/or abdominal complaints mostly without referral letters from their primary doctor. Six individuals unable or declining to read our questionnaire were excluded. Data input was controlled by a randomised sampling of 218 patients. We found a data entry failure rate of 1,5% which was amended.

We excluded 63 individuals because of tentative diagnoses of inflammatory bowel disease (20), anal corticoid ointment harm (28), condyloma acuminate (8), anal abscess (4), anal carcinoma (1), M. Bowen (1), and HIV lesion (1), leaving 807 patients for further calculation. Of these 807 individuals, 539 patients (66.8%) were found to have BAD, while 268 (33,2%) participants did not have BAD (table 5).

Table 5.

Participant characteristics at study entry

| Participants with BAD | Participants without BAD | P values (t-test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 539 | 268 | NS* |

| Males (number, %) | 238 (44.2%) | 124 (46.3%) | |

| Age all (mean+/-standard deviation, years) Men Woman | 56.5 (+/-15.0) 54.5 (+/-15.5) 58.0 (+/-14.4) | 48.3 (+/-15.9) 48.9 (+/-16.0) 47.8 (+/-15.9) | < 0.01 < 0.01 < 0.01 |

| BMI all (mean +/- standard deviation) Men Woman | 26.3 +/-4.3 26.5 +/-3.4 26.1 +/-4.9 | 24.3 +/-4,6 25.2 +/-4.1 23.5 +/-4.9 | < 0.01 < 0.01 < 0.01 |

* = Fisher's exact test

Of 539 patients with BAD, 168 patients (31.2%) presented with MAL (table 6). Haemorrhoids and pruritus ani followed by anal fissures were found most frequently in patients with BAD in contrast to patients with MAL, who mostly presented with anal fissures, thrombosed external haemorrhoids, and pruritus ani (table 6).

Table 6.

Types and frequencies of BAD in 539 patients. Comparison of types and frequencies of BAD in patients with one BAD vs. patients with MAL

| Types of BAD | Total number (%) of individuals with BAD | Patients with one BAD N (%) | Patients with MAL N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haemorrhoids | 401 (100.0) | 296 (73.8) | 105 (26.2) |

| Pruritus ani | 317 (100.0) | 155 (48.9) | 162 (51.1) |

| Fissure-in-ano | 70 (100.0) | 5 (07.1) | 65 (92.9) |

| Thrombosed external haemorrhoids | 29 (100.0) | 5 (17.2) | 24 (82.8) |

| Anal fistula | 4 (100.0) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) |

| Total number | 539 (100.0) | 371 (68.8) | 168 (31.2) |

Stage 2 was by far the most frequently found stage in 317 patients presenting with pruritus ani. Only stage 1 pruritus ani as a single lesion presented more frequently (table 7).

Table 7.

Distribution of pruritus ani stages in 317 patients with pruritus ani and comparison of pruritus ani stages in 155 patients with exclusive pruritus ani vs.162 patients with MAL

| Stages of pruritus ani | Total number (%) of patients with pruritus ani N (%) | Patients with pruritus ani solely N (%) | Patients with MAL N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| mild (stage 1) | 91 (28.7) | 91 (58.7) | 0 (00.00) |

| moderate (stage 2) | 178 (56.2) | 43 (27.2) | 135 (83.3) |

| severe (stage 3) | 29 (09.1) | 14 (9.0) | 15 (9.3) |

| chronic (stage 4) | 19 (06.0) | 7 (4.5) | 12 (7.4) |

| All | 317 (100.0) | 155(100.0) | 162 (100.0) |

At least one CAF was observed in 408 of 807 patients (50,6%). Such CAFs were found considerably more often in individuals with than without BAD. The differences between the BAD and the no BAD group with regard to skin tags and a funnel-shaped anus were highly significant (table 8).

Table 8.

Types and frequencies of CAF in 807 and in patients with and without BAD

| Types of CAF | Total number of patients with CAF N (%) | Patients with BAD (N=539) N (%) | Individuals without BAD (N=268) N (%) | P values (Fisher's exact test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin tags | 237 (29.4) | 177 (32.8%) | 60 (22.4%) | P< 0.01 |

| Funnel-shaped anus | 140 (17.3) | 112 (20.8%) | 28 (10.4%) | P< 0.01 |

| Hairy anus | 86 (10.7) | 59 (10.9%) | 27 (10.1%) | NS |

| Anal comedones | 9 (1.1) | 5 (0.9%) | 4 (1.5%) | NS |

| Hypertrophied anal papillae | 7 (0.9) | 4 (0.8%) | 3 (1.2%) | NS |

Of 807 participants, 188 (34.9%) with BAD and 105 (39.5%) without BAD did not specify symptoms. Therefore we are only able to present the answers of the remaining 350 and 161 individuals with and without BAD respectively (table 9).

Table 9.

Types and frequencies of symptoms and signs specified by patients with BAD and individuals without BAD. Nominations are presented since participants stand a chance to tick more than one symptom or sign into patients' questionnaire.

| Symptoms or signs asked in patients' questionnaire | "Yes" response of 350 patients with BAD N (%) | "Yes" response of 161 individuals without BAD N (%) | P values (Fisher's exact test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding in toilet paper, faeces or lavatory | 205 ( 58,6) | 86 ( 53,4) | NS |

| Anal itching | 153 ( 43,7) | 68 ( 42,2) | NS |

| Anal pain or discomfort | 118 ( 33,7) | 46 ( 28,6) | NS |

| Anal burning (baking) | 115 ( 32,9) | 51 ( 31,7) | NS |

| Anal soreness | 93 ( 26,6) | 26 ( 16,1) | P<0.05 |

| Anal lump | 83 ( 23,7) | 37 ( 23,0) | NS |

| Faecal soiling | 63 ( 18,0) | 26 ( 16,1) | NS |

| Anal weeping | 49 ( 14,0) | 12 ( 07,5) | P<0.05 |

| Anal mucous | 32 ( 09,1) | 30 ( 18,6) | P<0.01 |

| Anal incontinence | 24 ( 06,9) | 17 ( 10,6) | NS |

| Diarrhoea | 52 (14,9) | 37 (23,0) | P<0.05 |

| Constipation | 50 (14,3) | 26 (16,1) | NS |

| Abdominal pain | 47 (13,4) | 34 (21,1) | P<0.05 |

| Positive FOBT | 21 ( 6,0) | 4 ( 2,5) | NS |

| Anaemia | 4 ( 1,1) | 3 ( 1,9) | NS |

| Elevated tumour markers | 0 ( 0,0) | 1 (0,6) | NS |

| Screening colonoscopy | 62 (17,7) | 22 (13,7) | NS |

| Other causes | 17 ( 4,9) | 13 ( 8,1) | NS |

To determine whether certain symptoms could serve as predictors of BAD, we used binary logistic regression analysis. The database consisted of all 17 symptoms described in the questionnaire (table 1): Haemorrhoids were predicted by anal bleeding (p=0.032), anal weeping (p=0.017), non-existence of diarrhoea (p=0.008), and anal pain (p=0.005). Thrombosed external haemorrhoids were predicted by anal lumps (p<0.001) while anal bleeding (p=0.010) was absent. Anal fissures were predicted by anal pain (p<0.001) and anal bleeding (p=0.006) in the absence of anal weeping (p=0.033). Pruritus ani was predicted by anal pain (p<0.001), anal itch (p=0.001), and anal soreness (p=0.006).

For patients with MAL, we were interested whether it would be possible to differentiate among existing BADs using the symptoms described by the questionnaire. Sufficient numbers of patients were only available for haemorrhoids. We found that patients with haemorrhoids combined with pruritus ani stages 2-4 complained more often of anal itch (p<0.001), anal burning (p<0.05), anal soreness (p=0.001), and anal weeping (p=0.001) than patients with haemorrhoids only.

Individuals with and without BAD suffered from symptoms and signs for 2 to 12 months (29.3% vs. 34.4%) or more than 12 months (31,6% vs. 28,8%) before seeking help from a doctor, in contrast to those who came after "up to one week" (11.6% vs. 7.5%) or "within 2 to 4 weeks" (27.5% vs. 29.4%).

Individuals without BAD who tended to be younger (table 5), decided significantly more often to see their doctor immediately when symptoms appeared as compared to patients with BAD who tended to be older. Correspondingly, individuals without BAD treated themselves significantly less frequently (table 10).

Table 10.

Choices of treatment modalities for patients complaining of anal and/or abdominal symptoms and having BAD vs. individuals without BAD

| 260 patients with BAD* N (%) | 125 individuals without BAD** N (%) | Pearson Chi-Square Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I treated myself | 82 (31.5) | 25 (20.0) | P<0.05 |

| First I treated myself than I visited my doctor | 59 (22.7) | 24 (19.2) | NS |

| I did not treat myself but visited my doctor immediately | 119 (45.8) | 76 (60.8) | P<0.05 |

* = 90 individuals did not answer this question; ** = 141 individuals did not answer this question.

Discussion

The key to diagnoses of anorectal diseases remains the patient history, with confirmation by visual inspection, anoscopy, and rectoscopy 1,5,10,13,16. So far, diagnostics often exclude more serious causes of anal bleeding such as colorectal cancer 6,7 since patients with anal complaints but without colorectal cancer are neglected. Anal bleeding, anal itch, anal pain or burning rank among the most common symptoms of anal diseases seen in primary care practices 10,13,25,26,27,28.

The utility of different examination positions for determination of the causes of anal symptoms is unknown 1,2,4,6,7,14,27. The knee-chest position may provide a better field of view than broadly used left lateral Sims' position, as the buttocks fall to each side, and finger tips of both hands of the investigator are free for gentle eversion of the anal skin with the help of a good lighting 5,14. A fundamental drawback might be that haemorrhoids could be found less frequently with the knee-chest position because of the sloping position of the patient: the large intestine is pulled down towards the patients' head so that the haemorrhoids are unable to protrude. The left lateral Sims' position is more comfortable and patients achieve it easily and quickly by themselves; thus the investigating physician saves time by not having to position the patient.

Anal dermatologic problems can be trivialised by physicians and surgeons and overemphasized by dermatologists. Proctologic patients often receive conflicting opinions from clinicians 3,13,14,24,26,27 since with different specialists, the labelling changes for various disorders. As noted by Alexander-Williams 26 "Perianal dermatitis is an umbrella term". Pruritus ani was the second most frequent BAD after haemorrhoids in our study (table 6), possibly because we used the knee-chest position with its clear view of the anal verge 14. Our definitions of perianal dermatitis/pruritus ani stages are based on those reported in the literature 5,17,18,19,22,23 and are descriptive only, avoiding causative suggestions 3,14,24. The four stages illustrate transformation of the anal skin along a time course (figures 6,7,14) from acute to chronic, according to our experience 3,14,24, and those of others 10,17,18,22. Stage 1, defined as pain during palpation of the anal canal and/or anoscopy, is a well known phenomenon not always considered relevant when the physician's finger or the anoscope touches the exquisitely sensitive squamous epithelium distal to the dentate line 6. It may indicate mild irritation/inflammation of anal skin (table 3).

Figure 6.

Red dry skin with bleeding spots (stage 2 of pruritus ani, definition table 3) at a patient with a hairy anus (definition table 4).

Figure 7.

Weeping anal skin with superficial round splits and longitudinal superficial lesions (stage 2 of pruritus ani, definition table 3) at everted distal anal canal. Normally the distal anal canal is closed so that these tiny, passing lesions are not seen. Lesions diameter: 1 - 3 mm.

Figure 14.

Hairy anus. Hairs spread out almost carpet like to the anal verge (definition table 4).

MAL presented in almost one third (31.2%) of our patients with BAD (table 6). This is similar to other reports describing patients with three, four or five separate causes of anal itching 17,18,29. Thus until all causes of patients complaints have been eliminated, the patients are unlikely to experience relief of symptoms 5,29. At least one CAF was found in half (50.6%) of our patients. The meaning of this finding was unclear 5,24. However since we found that patients with BAD have highly significant more CAF than those patients without CAF (P< 0,01), it is possible that CAF may play a role in the pathogenesis of BAD (table 8).

Published symptoms of haemorrhoids are bleeding, prolapsing tissue, mucosal or faecal soiling, fullness after defecation, itching and pain 6,7. Haemorrhoids themselves can not be painful or itchy, since there are no sensory nerve fibres above the dentate line where haemorrhoids are derived 3,6,7,13,24. Therefore it is understandable that our patients with MAL differed in their spectra of symptoms compared to patients with only one BAD. The spectra of symptoms in these patients suggest that they have more than one BAD to diagnose and to treat 3,12,24,29. Interestingly our patients with BAD and without BAD did not differ much concerning their symptoms, with the exception of specific anal complaints like anal soreness (P<0.05), and anal weeping (P<0.05), both of which are suggestive of pruritus ani (table 9).

Ethics and Patient Consent

Investigations have been performed in accordance with the principles of DECLARATION OF HELSINKI. Informed consent from each patient has been obtained.

Figure 1.

Protruding haemorrhoids combined with skin tags around the anus (definitions table 2 and table 4).

Figure 2.

Chronic anterior anal fissure, diameter of 5-8mm, combined with a leftlateral thrombosed external haemorrhoid (definitions table 2).

Figure 3.

Posterior cavity, diameter 10x5mm, representing an old chronic anal fissure which has healed as indicated by a blanket of an epithelial layer.

Figure 4.

Non perforated leftlateral thrombosed external haemorrhoid (definition table 2), diameter 10 - 15 mm with an anterior skin tag (definition table 4).

Figure 5.

Unremarkable (normal) anal verge with hairs shaved (tiny black spots around the anus).

Figure 8.

Reddened, weeping skin, with superficial ulcers and excoriations disrupted by pale, whitish areas with no more hairs (stage 3 of pruritus ani, definition table 3).

Figure 9.

Red superficial lesions situated in whitish areas of anal skin covering skin tags situated around the anus (stage 3 of pruritus ani, definition table 3).

Figure 10.

Pale, whitened, thickened, dry, leathery, scaly skin with no hairs and no superficial ulcers or excoriations (stage 4 of pruritus ani, definition table 3).

Figure 11.

Whitish, pale, dry anal skin at anal verge including thickened, leathery surrounding skin tags (stage 4 of pruritus ani, definition table 3).

Figure 12.

Funnel shaped anus the buttocks being permanent in touch. They leave if parted a brownish border at its extreme edges (definition table 4).

Figure 13.

Funnel shaped anus. A red anterior border indicates its extreme edges. Skin tags, a longitudinal split at rima ani indicates local inflammation (stage 2 of pruritus ani).

References

- 1.Mazier WP. Hemorrhoids, fissures, and pruritus ani. Surg Clin N Am. 1994;74:1277–9. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46480-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madoff RD. Pharmacologic therapy for anal fissure. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:257–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801223380410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohde H, Christ H. Hämorrhoiden werden zu häufig vermutet und behandelt. Dtsch Med Wschr. 2004;129:1965–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-831833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nisar PJ, Scholefield JH. Managing haemorrhoids. Brit Med J. 2003;327(7419):847–1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7419.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lockhart-Mummery H.E. Non-venereal lesions of the anal region. Brit J vener Dis. 1963;39:15–7. doi: 10.1136/sti.39.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfenninger JL. Modern treatments of internal haemorrhoids. Brit Med J. 1997;314:1211–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7089.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brisinda H. How to treat haemorrhoids. Brit Med J. 2000;321:582–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7261.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gazet JC, Redding W, Rickett JW.The prevalence of haemorrhoids. A preliminary survey Proc R Soc Med 197063suppl780 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. The prevalence of haemorrhoids and chronic constipation. An epidemiologic study. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(2):380–6. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90828-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagle D, Rolandelli RH. Primary care office management of perianal and anal diseases. Primary Care. 1996;23:609–20. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70350-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson RL. Editorial comment. In: Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A. Temporal changes in the occurrence of haemorrhoids in the United States and England. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:585–91. doi: 10.1007/BF02049899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohde H. Was sind Hämorrhoiden? Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 2005;102(4):209–13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hancock BD. Haemorrhoids. Brit Med J. 1992;304:1042–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6833.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohde H. Diagnostic errors. Lancet. 2000;356(7.Oct):1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)73886-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rohde H. Mehrfach-Läsionen. Dtsch Med Wschr. 2002;127(38):1951–2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hancock BD. Anal fissures and fistulas. Brit Med J. 1992;304:904–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6831.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brossy JJ. Pruritus ani. Proc Roy Soc Med. 1955;48:499–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gayle LD, Longo WE, Vernava AM. Pruritus ani. Causes and Concerns. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:670–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02054410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granet E. Pruritus ani: the etiologic factors and treatment in 100 cases. N Engl J Med. 1940;223:1015–20. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mentha J, Neiger A, Mangold R. Entzündungen des Anus und Hämorrhoiden. Praxis. Schweiz Rundsch Medizin. 1961;30:752–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fazio VW, Fjandra JJ. The management of perianal diseases. Adv Surg. 1996;29:59–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tucker CC, Hellwig CA. Pruritus ani: histologic picture in forty-three cases. Arch Surg. 1937;34:929–38. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith LE, Henrichs D, McCullah RD. Prospective studies on the etiology and treatment of pruritus ani. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:358–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02553616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rohde H. Textbook of Proctology. Stuttgart New York: Georg Thieme Verlag; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aucoin EJ. Pruritus ani. Postgr Med J. 1987;82:76–4. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1987.11700057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexander-Williams J. Pruritus ani. Brit Med J. 1983;287:159–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6386.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metcalf A. Anorectal disorders. Five common causes of pain, itching, and bleeding. Postgrad Med J. 1995;98(5):81–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson LR. Treatment of anal fissure. Brit Med J. 2003;327:354–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7411.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowyer A. A study of 200 patients with pruritus ani. Proc Roy Soc Med. 1970;63:96–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]