Summary

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is the clinical use of current best available evidence from relevant, valid research. Provision of evidence-based healthcare is the most ethical way to practise as it integrates up-to-date patient-oriented research into the clinical decision-making to improve patients' outcomes. This article provides tips for teachers to teach clinical trainees the final two steps of EBM: integrating evidence with clinical judgement and bringing about change.

Introduction

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is an essential part of clinical practice. To be most effective, EBM should be used judiciously in appropriate clinical circumstances. In part one of this series we have suggested some practical tips for teaching the first three steps of EBM within a clinical learning environment so that trainees can grasp the initial elements of EBM (Box 1). These steps teach trainees how to search for and assess the quality of the evidence. But this in itself is not sufficient to effect beneficial changes to patient care. To make a real difference in patient outcome, the evidence needs to be integrated into clinical decision-making. The fourth and fifth steps in EBM revolve around putting the evidence into clinical practice: trainees must be taught how to apply EBM in actual clinical scenarios. In the absence of clinical integration, trainees may become disillusioned; they might see EBM activities as mere academic exercises far removed from reality. We reviewed the principles of adult learning in the first part of this series,1,2 and will refer to those principles time and again to put the suggested teaching model in perspective. It is of utmost importance to develop appropriate attitudes, behaviours and skills among trainees by focused guidance on clinical application of evidence by the teacher. In this second article we suggest some tips for teaching trainees how to make evidence-based practice a natural and spontaneous part of their day-to-day clinical life.

Box 1. Elements of EBM for clinical integration.

Formulating clinical questions

Tracking down the best evidence with which to answer that question

Critically appraising that evidence for its validity (closeness to the truth), impact (size of the effect), reliability (precision) and applicability (potential for improving outcomes)

Integrating the findings of critical appraisal with clinical judgement

Bringing about change—implementing the evidence from research into practice

Step 4: integrating EBM with clinical judgment, taking into account clinical circumstances, choices and values

The cycle of EBM starts by generating questions from a patient's clinical condition. After searching and critically appraising the evidence it is necessary to come back to that particular patient. Evidence on its own must not be applied blindly without due consideration for a patient's individual clinical circumstances. So how can trainees be taught the art of assimilating evidence into clinical practice?

It is crucial to apply the principles of adult learning in order to successfully teach trainees how to integrate EBM into clinical practice. As adult learners, trainees need to see that professional development learning and their day-to-day activities are related and relevant: they need direct, concrete experiences in which to apply their learning to the real world.

At this stage, trainees should be taught to consider the following issues before applying the evidences to patient care: assessing the quality of the evidence, the characteristics of the patient and the clinical setting, the patient's baseline risk, whether the patient will benefit from treatment, and preferences and values of the patients.

Quality of evidence

It is essential to assess the quality of the evidence. Low quality studies decrease the strength of the results and reduce the evidence for their application in real life. Once trainees acquire the skill of critical appraisal of a research evidence,2 they can be expected to make a judgment about the quality of the evidence with reasonable confidence.

Characteristics of the patient and clinical setting

How do the characteristics of the individual patient and clinical setting in real life compare with the population group and setting studied in the research? One of the criticisms of EBM is that evidence does not apply to patients in a setting different to that in the research. To address this issue it is important to look into the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study to assess the similarities and dissimilarities in the clinical situation between the study group and the real-life patient. If the patient meets all relevant inclusion criteria and does not contravene the exclusion criteria, the results of the study can be applied with confidence.

More often than not, patient characteristics in the clinical setting differ from the study population in some respect. In this situation teachers need to demonstrate to trainees how clinical judgement should be used to determine the extent to which research evidence can be extrapolated to their patient and setting. A pragmatic approach to deal with this dilemma would be to ask whether there is some strong reason not to apply the results in clinical scenarios. In most cases, it is acceptable to safely extrapolate study results to real life, even if the baseline characteristics of the patient deviate a little from the average study patient.

A simple example illustrates the issue: to find evidence for the use of corticosteroids to prevent respiratory distress syndrome in the neonate of a 23-year-old primigravida at 30 weeks' gestation in preterm labour, we looked into the meta-analysis of studies with similar patient characteristics. It is clear that the patient fits the spectrum of patients included in the meta-analysis and therefore the evidence can be safely applied in this clinical scenario (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Baseline risk

The patient's baseline risk is a key dimension in assessing whether any treatment is worthwhile for the individual situation; it refers to the patient's risk of developing a certain outcome ( Box 2). In the example above, this would be giving birth to a baby with respiratory distress syndrome without the use of corticosteroids. When the patient satisfies all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria of the studies in the meta-analysis, the baseline risk is similar to that of the control group. We simply take the frequency of the event (‘event rate’) in the control group. However, the risk of the patient might differ somewhat from the average risk of the study patients. She might have more or less concomitant disease, or a more or less severe manifestation of the disease. Additional poor prognostic factors might be present or absent (e.g. the patient might be at an earlier or later stage of gestation). At earlier stages of gestation the risk of respiratory distress syndrome will be higher, whereas at later stages it will be lower. Since these factors will influence the net benefit the patient will gain from the treatment, it is important to assess the individual patient's risk. The baseline risk will modify the absolute benefit the patient might experience from the treatment. Patients with a higher baseline risk tend to experience a higher absolute benefit. Sometimes it is necessary to be pragmatic and to make a ‘best guess’ approach based on what is known about the patient and the disease process and come up with a balanced judgement.

Box 2. Tips for assessing the baseline risk of a patient.

Look in the control group of the included trials

Look for a high quality prognostic study

Look in the control group of similar trials (subgroup meta-analysis) where the patient fits the inclusion criteria best

Employ the ‘best guess’ approach whether the risk and prognostic factors of the patient increase or decrease her baseline risk compared to the typical study patient

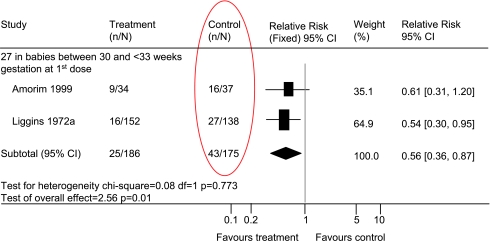

For the patient in our example, we identified the results of two randomized controlled trials that were included in a subgroup meta-analysis3 (Figure 1). In the two studies, 43 of 175 mothers in the control group gave birth to babies with respiratory distress syndrome, giving a 24% risk for respiratory distress syndrome without treatment. These data can be used to estimate the baseline risk of an individual patient.

Figure 1.

Forest plot in a subgroup meta-analysis3

Benefit to the patient

Once trainees have assessed the patient's baseline risk, they can be taught how to find as to which patient will benefit from the treatment. At this point it is worthwhile to advise trainees to revisit the concept of number needed to treat (NNT). NNT is an easy way of assessing the potential benefit of a treatment to a particular patient. In simple terms, NNT provides a measure of the number of patients who need to be treated to prevent one negative outcome.

Clinicians like to believe that each patient would benefit from the treatment they prescribe. A little bit of reflection reveals that in most situations, a considerable number of patients at risk will not develop either the disease or any complications of the disease. In our example, only 24 of 100 patients will have a baby with respiratory distress syndrome – 76 will not. If all 100 patients are treated, a considerable number of patients will develop the disease, and/or its complications, despite the treatment. For example, given a relative risk value of 0.60, we would expect 14 of 100 treated patients to have a baby with respiratory distress syndrome. This means that only in 10 patients of 100 will the intervention truly make a difference to the outcome. This small group of patients is captured in the NNT calculation, which shows that on average we will have to treat 10 patients for one to see a benefit ( Figure 2).

Figure 2.

- Baseline risk or control event rate = 24%

- RR × Baseline risk = experimental event rate = 0.6 × 24 = 14%

- Absolute risk difference = 24 – 14 = 10%

- NNT = (1/10) × 100 = 10

A large NNT indicates that the intervention does not make a difference to a large group of patients, whereas a small NNT means that even if a small group of patients is treated, the intervention will result in a real difference in the outcome.

One of the questions often raised is whether statistically significant P values mean that results can be directly applied to patients. Unfortunately a statistically significant result does not necessarily imply that the result is also of clinical importance and relevant for the patient. This is always a matter of judgment that is influenced by:

The severity of the event that should be prevented by the intervention. For instance, most people would judge transient tachypnea of a newborn as less severe than respiratory distress syndrome.

The patient's risk for an adverse event if the condition is left untreated. Most people would judge an event less worth preventing if the bad event occurs in one of 1000 patients than an event which occurs in 300 of 1000 patients.

In the same way, many people might judge an effect as not clinically relevant if only one of 100 treated patients will benefit from the treatment (i.e. an NNT of 100) compared to an intervention where 30 of 100 treated patients will benefit from the intervention (i.e. an NNT of 33).

It is also important to look at the benefits and weight them against the potential harms that could be associated with the treatment. If, for instance, a drug treatment reduces the risk of respiratory distress syndrome but increases the risk of neonatal sepsis, most people would question the clinical importance of the benefit (Box 3).

Box 3. Determinants of clinical importance.

A statistically significant result does not tell physicians or patients whether it is also of clinical importance. Clinical importance includes:

a judgment about the severity of the event to be prevented

the patient's risk of an adverse event if left untreated

the absolute benefit for the patient in reducing the risk for the negative event

the potential harm associated with the intervention and the burden to the patient

Balancing benefit and harm

By now, the trainees should have learnt that corticosteroids are effective in preventing respiratory distress syndrome in preterm babies. We know that baseline risk of patients without treatment is important when estimating NNT and how to assess for clinical importance. Is there any harm against which the benefit should be weighed? For the maternal effects evaluated in the meta-analysis,3 there appears to be no risk of sepsis. But sometimes the difference between reduction in the events we would like to prevent versus the unwanted adverse events can be so small that benefit may not be considered worthwhile ( Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparing benefit and harm of corticosteroid therapy

| Benefit | Harm |

|---|---|

| Effect of corticosteroid therapy on respiratory distress syndrome: | Effect of corticosteroid therapy on the risk of puerperal sepsis |

| • Observed events without treatment: 43/175 | • Relative risk (RR): 1.10 (95% CI: 0.61 to 2.00) |

| • Relative risk (RR): 0.60 (95% CI: 0.52 to 0.71) | |

| • NNT: 10 |

Patient preferences

The preferences and values of the patient are also important determinants of whether a research finding can be applied to an individual patient's management. Ultimately, practicing EBM requires a judicious mix of the best available evidence, clinical expertise and the patient's preferences and values. Robotic adherence to guidelines or research findings should not be the goal of even the most ardent EBM enthusiast. Each patient and caregiver, and their particular circumstances, have distinct differences, and the guidelines may not be applicable in the same way to every patient. EBM is a valuable and indispensable tool for today's busy clinicians, but it is a tool that should always be used within the clinical context of an individual patient.

Trainees should be encouraged to involve patients in the clinical decision-making process, as this is good medical practice, improves patient satisfaction and reduces the chances of litigation and complaints. This can be achieved if clinicians provide the necessary evidence and context-based information to help patients make an informed choice.4

Let us consider another scenario in which the patient accepts the use of corticosteroids but requests the use of antibiotics, as her sister also received antibiotics in similar circumstances to prevent infection. To address this concern, systematic reviews in Cochrane Library are searched for the use of antibiotics in preterm labour with intact membranes.5 This search reveals no effect on respiratory distress syndrome (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.84–1.16) with the use of antibiotics and a possible increase in risk of neonatal death (RR 1.52, 95% CI 0.99–2.34).

In our example case, we set out to search evidence for the use of corticosteroids to prevent respiratory distress syndrome in the neonate of a 23-year-old primigravida at 30 weeks' gestation in preterm labour. Baseline risk of the patient for developing respiratory distress syndrome is 5% at 30–32 completed weeks' gestation. Treatment options with corticosteroids and antibiotics were discussed. Risk for respiratory distress syndrome is reduced by 40% (RR 0.60) while the risk of puerperal sepsis is not increased. We addressed the patient's concern about infection and found that antibiotics were not beneficial but potentially harmful. Thus the shared decision with the patient was to use corticosteroids only.

Points to remember

It is crucial to remember that EBM is particularly useful for good medical practice when good evidence exists. At the same time, it is true that it is impossible to find good evidence for every single type of clinical uncertainty. Where there is no evidence, clinical judgment should be employed to determine the best possible patient care.

Probably the most crucial thing for teachers to teach and for trainees to learn regarding EBM is how to transfer knowledge gained from research into individual patient care. As adult learning theory suggests, transfer of learning for adults is not automatic and must be facilitated. Coaching and other kinds of follow-up support are needed to help adult learners transfer learning into daily practice so that it is sustained. Clinicians take all the points mentioned above into consideration while counselling patients or while discussing management options with the patients. Initially the trainees should observe their seniors and learn how to integrate evidence into patient care and how to formulate a management plan jointly with the patient. It is the responsibility of the teachers to demonstrate the key elements of EBM to the trainees. Appropriate communication skill is vital to convey the right message to the right person in the right manner. Organizing small group activities to practise this step is an excellent way to develop this skill and help trainees to be confident in interacting with patients in real life. Adult learning principles encourage small group activities during learning to move beyond understanding to application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation. Small group activities provide trainees with an opportunity to share, reflect and generalize their learning experiences. In the next step trainees should be supervised by the trainers and fed back regularly so that they become fully conversant in the art of integrating EBM into clinical practice.

As adult learners they need to receive feedback on how they are doing and the results of their efforts. Appropriate assessment mechanisms must be built into professional development activities that allow trainees to practice what they have learnt and receive structured, helpful feedback. Assessing the practice of EBM may seem to be a daunting task, but in practice it is relatively easier than teaching it. Various tools have been developed to assess trainees. Completed assessment forms are essential components in each and every trainee's portfolio.

Objective Structured Assessment of Technical skill (OSAT) or Direct Observation of Procedural Skills (DOPS) can be used to assess trainees' knowledge of research evidence for procedures and their ability to integrate that in their practice. For example, OSAT for a Caesarean section can quite easily demonstrate trainees' knowledge of and ability to integrate the NICE guidelines6 in an appropriate clinical situation. Case-based discussions are retrospective assessment tools where trainees can demonstrate their knowledge, awareness and application of evidence in managing a patient. Mini clinical examinations are real-life scenarios where trainees communication skills, knowledge of evidence, ability to make a balanced judgement in the clinical management of a particular patient and communicate it effectively to the patient to draw a management plan can be assessed first-hand. Multi-source feedback (360° assessment) can employ mini-peer assessment tool or team assessment behaviour to invite the views of clinical librarians and audit departments to examine a trainee's learning and use of EBM.7

Senior clinicians use these assessment tools all the time to assess their juniors. With a keen awareness of EBM on the trainer's and trainee's part, these assessment tools can easily be used to assess knowledge, technical skills and ability to integrate EBM into clinical practice.

Step 5: bringing about change – implementing the evidence

When a trainee acquires the skills of gathering and appraising evidence, learns how to apply these skills in everyday clinical situations and continue to do so, part of the objectives of EBM have been achieved: bringing about changes in knowledge, skill, attitude and behaviour of the trainees. Though this achievement is significant at a personal level for the trainee, the benefit to patients may still be patchy and fragmented. Once trainees realize their own achievement, they should be congratulated for their effort and should be encouraged to play a bigger role in evaluating current practice in the light of newer evidence. This practice can be successfully established in the form of trainee presentations in journal clubs8 or clinical meetings. When new evidence suggests a change in existing practice, teachers should guide the trainees to find out potential areas for change within the organization after taking local issues into consideration.

Bringing about change at the organizational level is a complex process ( Box 4). Once evidence is gathered and its validity and applicability to local patients assessed, and the need to change practice seems appropriate, it is necessary to inform all the relevant healthcare providers who are likely to play a key role in implementation. It is important to convince opinion leaders about the need for change. They may be experienced clinicians who are well networked but who themselves may not be well versed in the principles of EBM. It is extremely useful to work closely with them to utilize their skills, connections and power of persuasion to convince people of the need to change practice in the light of newer evidence. Ultimately the key persons to bring about the change are the decision-makers – usually persons with authority such as the clinical director of a hospital or clinic – but they play a rather formal role in the whole process. They need to be persuaded in order for the evidence to be implemented as a new policy for patient care. The implementation step that follows the decision relates to putting the new evidence-based policy (guidelines and protocols) of care in practice. There are potential barriers to be faced in almost every level in order to bring about a change. Assessment of the inherent worth of the evidence and the anticipated opposition to the resultant changes to practice are important variables in overcoming existing barriers.

Box 4. Tips for teaching how to bring about change in a clinical setting:

Identify potential areas in clinical practice where guidelines/protocols are outdated and new evidence has emerged

Identify potential areas in clinical practice where the need to change has been established as a priority

Focus on areas where small worthwhile changes can be quickly implemented

Discourage trainees from getting involved in areas where change is unlikely to occur by recognizing that not everything can be changed

Encourage them to prepare new guidelines/protocols or to revise the existing ones

Encourage them to participate in audit and guide them to incorporate evidence-based criteria in audit

Support them in presenting the audit findings to key stakeholders

Acknowledge their effort and congratulate them on their achievements, however small

Clinical guidelines9 usually combine research evidence derived from systematic reviews with the consensus views of experts. They may or may not take local circumstances and resources into account. Trainees should be encouraged to develop local guidelines and/or protocols based on the evidence found and implemented as a new policy for patient care. This is what leads to change in practice. In general, recommendations based on high quality evidence and supported by professional bodies, certain of improving patient outcomes and requiring small changes, are more likely to be adopted and implemented quickly. To avoid frustration for trainees, a realistic judgement should be made by trainers about the feasibility of change and the level of change achievable; teachers should identify these areas for trainees to get involved. For the trainees there is nothing more motivating than to see the implementation of a piece of work done during their time in training.

Clinical audit is one method for ensuring that organizations are doing what they think they are doing. It can provide valuable information to determine if evidence-based clinical guidance has been actioned locally and is being followed in practice. Trainees should be encouraged to undertake relevant audit projects, which are important components in the practice of EBM.

Many trainees will not have the opportunity of first-hand experience of the whole complex process of making change happen. However, they should be encouraged to be involved in preparing local protocols and conducting regular audits using evidence-based criteria. These are all part of the organizational change and trainees can play a significant part in it. Within their existing educational frameworks, trainees are expected to be involved in the preparation of guidelines, protocols and regular audit activities. With proper guidance by thoughtful teachers these activities can be successfully harnessed within the realm of EBM.

Evaluating the success of teaching EBM in a clinical setting

The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) is a freely accessible website (http://www.cebm.utoronto.ca/) developed by the Department of Medicine at Toronto General Hospital. The goal of the website is ‘to help develop, disseminate, and evaluate resources that can be used to practice and teach EBM for undergraduate, postgraduate and continuing education for health care professionals from a variety of clinical disciplines’.

A self-evaluation toolkit which can be used by the teachers of EBM is available at the website.10 It includes queries on subjects such as:

When did I last issue an educational prescription?

Am I helping my trainees learn how to ask answerable questions?

Am I teaching and modelling searching skills?

Am I teaching and modelling critical appraisal skills?

Am I teaching and modelling the generation of critically appraised topics?

Am I teaching and modelling the integration of best evidence with my clinical expertise and my patients' preferences?

Am I developing new ways of evaluating the effectiveness of my teaching?

Am I developing new EBM educational material?

Am I a member of an EBM-style journal club?

Have I participated in or tutored at one of the workshops on how to practise or teach EBM?

Have I joined the evidence-based health e-mail discussion group?

Have I established links with other practitioners or teachers of EBM? 7

Conclusion

We have suggested ideas for teachers to incorporate essential elements of EBM within their day-to-day interaction with trainees in a clinical setting. Not everyone needs to appraise evidence from scratch but everybody will invariably need some training to develop skills in EBM. We have shown how all the five steps of EBM, from question to application, can be successfully taught to trainees even within their busy schedules through a deliberate strategy based on the principles of adult learning.

Practice points

Clinically integrated teaching of EBM is more likely to bring about changes in skills, attitudes and behaviour

Assessment tools can be used to aid teaching of EBM

It is essential not to lose sight of the clinical problem at hand which initiated the search and appraisal of good quality evidence

EBM should be used as a useful adjunct to the decision-making process in individual patient management

Clinical practice should be assessed in the light of new evidence and appropriate changes should be made if needed.

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS —

Competing interests None declared

Funding None

Ethical approval Not required

Guarantor SM

Contributorship KD, SM and KSK jointly conceived the project. All of them contributed to the draft of the papers with KD contributing majority of Part 1 and SM contributing majority of Part 2. Khalid S Khan (KSK) supervised the project

Acknowledgements

None

References

- 1.Speck M. Best Practice in Professional Development for Sustained Educational Change. ERS Spectrum. 1996;Spring:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das K, Malick S, Khan KS. Tips for teaching evidence-based medicine in a clinical setting: lessons form adult learning theory. Part one. J R Soc Med. 2008;101:493–500. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.080712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts D, Dalziel S. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;3:CD004454. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004454.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH. Physicians' and patients' choices in evidence based practice. BMJ. 2002;324:1350. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7350.1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King J, Flenady V. Prophylactic antibiotics for inhibiting preterm labour with intact membranes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2002;4:CD000246. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute For Clinical Excellence. Caesarean Section. Clinical guideline. London: NICE; 2004. Apr 13, http://www.nice.org.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naeem A, Kent A, Vijayakrishnan A. Foundation programme assessment tools in psychiatry. Psychiatric Bull. 2007;31:427–30. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Afifi Y, Davis J, Khan KS, Publicover M, Gee H. The journal club: a modern model for better service and training. Obstet Gyncecol. 2006;8:186–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Prescribing Centre. Implementing NICE Guidance – A Practical Handbook for Professionals. London: NHS; 2001. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centre for Evidence Based Medicine. University health network. http://www.cebm.utoronto.ca/practise/evaluate/index.htm.