Abstract

Carbohydrate supplementation in prolonged aerobic exercise has been shown to be effective in improving performance and deferring fatigue. However, there is confounding evidence with regard to carbohydrate supplementation and tennis performance, which may be due to the limited number of studies on this topic. This evidence based review, using database searches of Medline and SPORTDiscus, summarises the limited relevant literature to determine if carbohydrate supplementation benefits tennis performance, and, if so, the appropriate amounts and timing. Although more research is required, it appears that it may be beneficial in tennis sessions lasting more than 90 minutes.

Keywords: nutrition, glucose, tennis, diet, glycogen, carbohydrate

Proper nutritional practices are important for optimum tennis performance. The importance of carbohydrate (CHO) as a substrate for contracting skeletal muscle and central nervous system function,1 as well as the importance of glucose concentrations in endurance performance,2 have been recognised. However, the study of CHO metabolism and benefits of dietary intake during tennis practice and competition has been limited. As tennis has semistructured rest periods (change of ends) every 10–15 minutes, it gives players the opportunity to regularly consume fluid and CHO in a structured fashion. A Medline search found 59 770 entries using the search word “carbohydrates”; however, only four entries came up when this was followed by the word “tennis”. A search for “glucose” found 271 117 entries, but only eight if the word “tennis” was added. It is clear that the knowledge and resources are available for in depth CHO metabolism studies in tennis, but not much research has yet been performed. As tennis involves long lasting matches and practices, with hundreds of short duration (<10 seconds) explosive bursts interspersed with short recovery periods (<30 seconds),3 it provides a different physiological stress from traditional laboratory endurance tests performed on a treadmill or cycle ergometer. This difference in movement patterns, with a large involvement of both upper and lower body muscles, as well as different cognitive and psychological demands, provides the athlete with different stressors from traditional, endurance based laboratory tests. These factors, combined with the irregular intensities of work and rest, are likely to produce different responses to CHO use and availability in tennis play from some more traditional types of endurance activity (running, swimming, cycling).

In two position stands, by the American College of Sports Medicine and the National Athletic Trainers Association, it has been recommended that athletes in general should consume 30–60 g/h CHO during exercise.4,5 The CHO can be in the form of glucose, sucrose, maltodextrins, or some high glycaemic starches. Fructose should be limited because of the possibility of gastrointestinal discomfort.4,5 This rate of CHO ingestion can be accomplished by drinking 600–1200 ml/h of a solution containing 4–8% CHO (4–8 g/100 ml).4,5

This is good general information for athletes and possibly a good general starting point for tennis players; however, the aim of this article is to explore the literature and attempt to provide more tennis specific, evidence based CHO supplementation guidelines. The literature on CHO metabolism in tennis was reviewed by searches using Medline and SPORTDiscus and by cross referencing these articles using the search phrases tennis/carbohydrates, tennis/glucose, tennis/glycogen, and tennis/metabolism.

Extended tennis play and hypoglycaemia

Maintaining appropriate muscle glycogen stores throughout practice or match conditions is important for performance.1 Hypoglycaemia has been shown to occur in healthy adults during submaximal, long duration exercise,6 but can also occur as transient rebound hypoglycaemia (also known as reactive hypoglycaemia: see the following section) at the start of exercise, resulting from incorrectly timed ingestion of CHOs with high glycaemic index.7,8 An increase in CHO oxidation and hypoglycaemic risk can be expected during long duration activity, especially in the heat.9

Although research on CHO utilisation during tennis play is limited, blood glucose concentrations in tennis players have been shown to remain stable during play lasting less than 90 minutes,10 but more surprisingly, also in competition lasting 180 minutes.11 Homoeostatic control of blood glucose concentration was also evident throughout an 85 minute match.10 Although the blood glucose concentration remained consistent during play, there was a non‐significant downward “trend.” This was probably due to the inability of hepatic glucose production (through gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis) to match the increased uptake of glucose by the contracting muscles.10 As exercise continues, however, blood glucose is increasingly used to support CHO oxidation. A longer test session (>85 minutes) might have elicited a stronger glucose response, as Burke et al,12 who measured glucose changes over a two hour simulated tennis match, concluded that, without ingestion of appropriate CHO at frequent intervals, blood glucose concentrations would probably fall during prolonged tennis play. This fall in blood glucose concentrations has been observed in non‐tennis specific endurance exercise lasting more than 90 minutes.2,6,13 This is why the findings of Mitchell et al11 that blood glucose did not fall below baseline during 180 minutes of tennis competition is somewhat surprising. They suggest that a possible reason for the stable blood glucose concentrations is that the tennis exercise performed (180 minutes tennis match play) may not place a heavy enough metabolic demand on the physiological system to make CHO supplementation necessary.11

Reactive hypoglycaemia

The ingestion of CHO‐rich solid or liquid foods within 45 minutes of the start of competition has been shown to cause a temporary rise in blood glucose concentrations followed by a sharp decline in both pre‐competition and between match research.7,8,14,15,16 However, this fall in blood glucose has not always been shown to lead to a decline in performance.16 This rebound effect is described in the literature as reactive hypoglycaemia and is linked to excessive insulin secretion.7,8,17 As there may be a detrimental effect to the athlete, it may be appropriate for tennis players to limit the consumption of CHO‐rich food within 45 minutes of competition or practice. If matches or practice sessions have only short rest periods between (less than one hour) or time constraints do not allow more than 45 minutes between CHO ingestion and exercise, the nutrients consumed should be in the form of easily digestible food in small amounts (<10 g CHO per 10 minutes) during the first part of the practice session or match, rather than within the 45 minutes before the match. This notion is supported in the literature.18

Carbohydrates and competition stress

Although there is limited information on the differences between practice and match conditions, one study has shown that tournaments/matches generate higher blood glucose concentrations than practice conditions.15 These competitive situations also induce much larger fluctuations in blood glucose concentration throughout the course of a tournament day than in a single session. The increased glucose concentrations under tournament (increased stress) conditions can be explained by an increase in sympathetic activity with heightened adrenaline (epinephrine) release. This large increase in adrenaline is not seen during practice.19

The higher concentration of blood glucose seen after the warm up for a singles match reflects an endocrine and metabolic pre‐start effect, which ensures rapid glycogenolytic adaptation to the sudden muscular glucose uptake at the start of exercise after the warm up.15 A close correlation (r = 0.693) between concentrations of capillary glucose and urinary adrenaline after a singles match supports this conclusion.15

Negative disturbances of glucose homoeostasis have been shown to occur during the rest period between the first and second match on the same day.15 In this study, while the players warmed up for the second match, there was a sudden fall in blood glucose concentration. However, it did not seem to affect competitiveness, which was measured by a non‐validated “energetic drive” subjective scale. This result is supported in the literature.16 There are five possible reasons for this hypoglycaemic‐type reaction, but it must be emphasised that no definite conclusions can be drawn because of lack of standardisation of studies under tournament conditions.15

Energy consumption increases during the transition from rest to exercise.

Possibly the second match of the day was less important (in this study it was doubles), and release of catecholamines was therefore significantly lower and a restrained glucose uptake because of limited substrate mobilisation was observed.

Efficient and rapid hepatic glycogenolysis is more difficult with increased depletion of both muscle and liver glycogen stores supported by the fact that glucose concentrations fell much more sharply at the start of doubles play after lengthy (three sets) matches than after short (two sets) matches. However, other factors that were not measured may have played a significant role.

Energy intake may be have been insufficient during the rest period between the first and second match, further magnifying glycogen depletion. A higher risk of hypoglycaemia can be expected at the start of the second match if insufficient externally supplied CHOs are provided.6

Snacks with a high glycaemic index immediately before the start of activity induce reactive hyperinsulinaemia synergistically with the effect of the muscle contractions, which lead to increased muscular glucose uptake at the start of exercise, causing a rebound fall in serum glucose concentrations.7 Misinformation about nutrient timing for tennis practice and matches can result in players eating a high CHO supplement before the second or even third match of the day, thinking that they are ingesting appropriate fuel to optimise performance, but instead causing them to feel the effects of hypoglycaemia (lethargy, headache, light headedness). As this has been observed anecdotally without any published studies, and this is an evidence based review, no strong conclusions can be made.

Although generally untested, these effects probably negatively affect performance. However, further research is needed in this area to produce appropriate guidelines on CHO consumption before play.

Carbohydrates and fatigue

Decreased CHO availability leads to fatigue in prolonged activity.20,21 Although other factors influence an athlete's capacity to withstand fatiguing exercise, depletion of muscle glycogen (because of its limited storage capacity) is a major factor contributing to fatigue in prolonged exercise.22 It has been proposed that working for an extended period (>90 minutes) at 55–75% of maximal oxygen uptake will probably lead to a large reduction in glucose and muscle glycogen.22 Tennis players have been shown to practice and play matches consistently within this maximal oxygen uptake range.10,23,24,25,26 Supplementing with CHOs during exercise has been shown to delay fatigue during long lasting, time to exhaustion and performance ride methods, as well as limiting glycogen depletion.1,27,28,29 These studies have different metabolic demands from those experienced during tennis play, and a reduction in tennis performance without CHO supplementation has not always been shown.11 In a study of cyclists working at an intensity similar to tennis players (70–75% of maximal oxygen uptake),20 it was found that CHO supplementation delayed time to fatigue by 33%.20 CHO supplementation has also been shown to improve performance in the later stages of prolonged tennis play30 and intermittent high intensity exercise similar to tennis.31

Even though supplementation with CHOs during continuous competitive tennis has been shown to stabilise blood glucose at a significantly higher concentration than a placebo,14 the placebo group showed only a marginal decrease toward the end of the competition. The competition lasted about four hours with only a marginal fall in blood glucose concentration within the last hour of exercise. This result is in opposition to the findings of larger reductions in blood glucose in controlled laboratory experiments.6,27 Possible reasons for the differences between field (on‐court) and laboratory experiments may be the psychological drive to perform, motivation, and hormonal (adrenaline) factors inherent in competitive situations. They may also be due to the difficulty of simulating tournament conditions in a practice setting as well as the difficulty of measuring tennis “performance.”

Although CHO supplementation does increase blood glucose concentration in tennis players, their overall performance—that is, playing success, as measured by games won and hitting accuracy—did not seem to benefit from CHO ingestion.14 Mitchell et al11 also found no performance benefit after three hours of tennis competition with CHO supplementation compared with a placebo. These conclusions11,14 are in opposition to the findings of Vergauwen et al30 that CHO supplementation did benefit hitting accuracy and stroke quality in the later stages of two hours of high level tennis training. These contradictory findings on CHO supplementation and tennis performance may be due to differences in the types of performance tests used, rest periods, environmental conditions, equipment (balls and rackets), fitness level of participants, and tennis ability. Most tennis performance tests used were brief hitting drills or short anaerobic tasks, which differ substantially from the time to exhaustion trials performed in a laboratory setting.6,13,27 For a more in depth discussion of the different tennis related performance tests, see Vergauwen et al.32 The only tennis specific study to show an improvement in performance with CHO supplementation used a volitional fatigue test to measure stroke accuracy.30 It appears from that research that CHO supplementation may help tennis players if match or practice sessions are at high enough intensity and long enough duration to approach volitional fatigue. However, the research on CHOs and performance in tennis is conflicting (table 1), and a need exists for further research. More evidence (non‐tennis specific) is accumulating, which recommends CHO ingestion during intermittent exercise that lasts more than 60 minutes, as this will delay or limit the onset of fatigue.33 This is in opposition to some of the aforementioned tennis research.11,14

Table 1 Effect of carbohydrate supplementation on tennis performance.

| Reference | Effect | Effective | Duration of tennisplay (minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | Improved stroke quality | Yes | 120 |

| 30 | Improved stroke quality | No | 120 |

| 14 | Improved tennis specific running speed, but had no effect on games won or hitting accuracy | Yes and no | 240 (with 30 min break at 120 min) |

| 11 | No performance benefit | No | 180 |

Caffeine and Carbohydrate metabolism

Although this is a review of CHOs in tennis, it would be remiss not to comment on the effect of caffeine on CHO metabolism. The effects of caffeine on performance have been speculated on in many different sporting environments. Not many studies have been conducted on caffeine supplementation in tennis players. The few that have been performed have shown minimal, if any, performance enhancement.14,15,34 Blood glucose concentrations have been shown to be the same whether the tennis player consumed a calorie‐free beverage with or without caffeine (130 mg/l),14,34 even though caffeine has been suggested to be a hyperglycaemic agent by stimulating glycogenolysis.35 It has also been found that caffeine has no influence on lipolysis when consumed in the test amounts (130 mg/l). This contradicts the observation of increased free fatty acid concentrations and fat oxidation after caffeine ingestion in another study.36 The difference may be explained by the lower dosage of caffeine used in that study was to simulate the concentration found in traditional caffeine soft drinks. A conclusion from the researchers was that caffeine (in the doses typically seen in commercially available soft drinks) was unlikely to have metabolic effects in tennis competition if ingested during tennis changeovers.14

In a different study which showed no performance benefits in tennis players when a dose of 364 mg (men) and 260 mg (women) of caffeine were ingested, the authors did suggest that caffeine may have some effect on the regulation of blood glucose at the start of play.34 This may benefit players who often experience symptoms related to hypoglycaemia. Ingestion of caffeine before the second or third match during a tournament day may help them to avoid reactive hypoglycaemia. These tennis specific “field” studies contradict some of the caffeine induced performance benefits (improved power output) seen in later stages of endurance exercise under laboratory conditions.37,38 These differences may be partly explained by the amount of caffeine ingested as well as the fact that the laboratory studies focused on continuous endurance exercise as opposed to the intermittent exercise in the tennis studies.

Carbohydrate ingestion before a practice/match

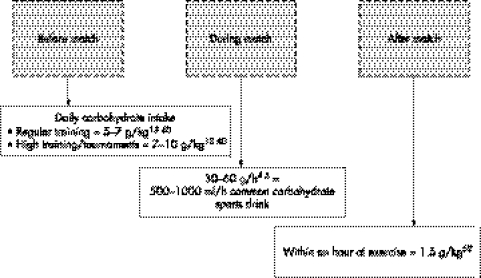

It is difficult for many tennis players to successfully follow a productive and effective eating programme. Many try to achieve this on tournament days, but eat poorly for one or two days before competition. This type of “crash course” nutrition has been shown not to be very effective for optimising CHO stores during competition.39 Athletes need to have an adequate daily energy intake. In an extensive review of CHO needs in athletes, Burke and colleagues40 put forward some general daily CHO guidelines.40 During general training, when intensity is moderate to high, athletes are recommended to consume 5–7 g/kg CHOs on a daily basis (fig 1).40 If training is increased and during tournament weeks, this should be increased to 7–10 g/kg daily to maintain sufficient energy stores for performance and to aid recovery (fig 1).13,40

Figure 1 A recommended tennis match carbohydrate intake regimen.

Carbohydrate ingestion during practice/match

A suggested general goal of CHO ingestion during exercise has been to provide 30–60 g/h (fig 1).4,5 Most commercial sports drinks provide 60–80 g/l CHOs; thus consuming 500–1000 ml per hour would provide adequate CHO replenishment.

The notion that more is better is not the case with CHO ingestion. Ingesting higher levels of CHOs (>60 g/h) does not increase oxidation rates and can lead to gastrointestinal discomfort.41 Is there a preferred type of CHO that should be consumed during exercise? All simple sugars are absorbed rapidly, and although the different forms do metabolise at slightly different rates, using different mechanisms, they seem to be equally effective in maintaining blood glucose concentrations during exercise.42 However, fructose should be limited, as it can lead to gastrointestinal discomfort.4,5 No differences in glucose or glycogen concentrations have been shown whether the consumption is in solid or liquid form.43 Clearly during hot weather, there is an advantage to liquids.

The timing of CHO ingestion during practice or competition should aim to create a regular flow of CHOs from the gut into the bloodstream. As CHO can be counterproductive when ingested in amounts (>60–90 g/h) or concentrations (>7–8%) that are too large,44,45 it may be advisable to ingest small amounts on a regular basis—for example, at each changeover—instead of consuming a large amount at a single changeover. It is inadvisable to provide a large amount of CHOs early in the practice or match and then refrain from providing any more. This may prime the body for glucose metabolism, and reduce fat oxidation, which may deprive the body of fuel that it has been primed to metabolise.33

Another added benefit to consuming a CHO/electrolyte beverage during prolonged exercise is that it has been shown to delay the onset of exercise induced muscle cramps.46 However, although it may delay muscle cramps, it has not been shown to prevent exercise induced muscle cramps.46

It is imperative that tennis athletes maintain a hydration status that will aid performance, as dehydration (>2%) increases the use of muscle glycogen during continuous exercise, possibly as a result of increased core temperature, reduced oxygen delivery, and/or catecholamines.47

Recovery Carbohydrate ingestion

CHO replenishment is a component of a tennis training programme. It may not only be important for tournament situations where multiple matches may be played on multiple days, but it could also be important during training periods to allow full recovery for a second session of practice on the same day or practice on following days.

What is already known on this topic

Carbohydrates are known to be beneficial in improving performance and reducing fatigue in long duration aerobic activity

Carbohydrate supplementation ranges are available for aerobic activities, but limited scientific research has been performed specifically on tennis play

What this study adds

This review adds some preliminary information on carbohydrates and tennis

It should stimulate more studies on tennis specific nutritional research as it appears that carbohydrate supplementation before, during, and after tennis play may benefit performance and limit fatigue

As the amount of glycogen that can be resynthesised within a given time period is limited, a major goal of CHO intake after tennis is to provide adequate CHOs for liver and muscle glycogen replacement before the next training session. Rates of glycogen synthesis are highest immediately after exercise.48 If CHOs are withheld for two hours after exercise, it reduces the rate of glycogen synthesis by 47%, compared with consuming CHO immediately after exercise.49 This accelerated rate of glycogen resynthesis is probably due to the insulin‐like effect of exercise on skeletal muscle.50 The type of CHO ingested is important. Ingestion of CHOs with high glycaemic index has been shown to result in a 48% greater rate of muscle glycogen resynthesis than the ingestion of CHOs with low glycaemic index 24 hours after exercise.51 It is recommended that players consume 1.5 g/kg CHO during the first hour after exercise (fig 1), but no greater benefit has been seen on muscle glycogen resynthesis when >1.5 g/kg CHO was ingested.52 For example, a 75 kg tennis player should consume about 113 g CHO within the first hour after exercise. The addition of 28 g protein to the CHO resulted in a 27% greater rate of muscle glycogen accumulation over four hours than the same fuel source without (80 g CHO and 6 g fat).53 However, this notion that protein aids muscle glycogen resynthesis has not been shown consistently.54

Conclusions and future research

High level tennis training is complex. Tournaments can last up to two weeks with matches lasting up to five hours. This requires a structured nutrition programme to maintain appropriate CHO concentrations before, during, and after tennis practice and competition. Tennis players show large variability in their metabolic responses, and therefore individual monitoring of CHOs should be encouraged.

It is known that CHO supplementation can delay symptoms of fatigue, and for optimal performance it is necessary that tennis players maintain glucose and glycogen stores at appropriate concentrations. However, if an adequate dietary programme is in place, limited CHO supplementation may be needed during single day practices or matches lasting less than two hours.

Nevertheless, CHO supplementation should take place before practices and matches, allowing at least 45 minutes before play. Athletes who ingest CHOs within 45 minutes of the start of exercise may suffer reactive hypoglycaemia, which is a quick spike in glucose concentrations followed immediately by a rapid and sharp decline, which results in lethargy, tiredness, and light‐headedness. Also, there does not seem to be a strong link between CHO supplementation during play lasting less than 90 minutes and improved tennis performance.

As there is a scarcity of tennis specific CHO research, the aim of this review was to put forward some preliminary suggestions and highlight the need for more research in this area. As the results on CHO supplementation and tennis performance are confounding, there is a clear need to determine whether traditional CHO ingestion in the amounts found in commonly used sports drinks actually aids tennis performance. As most research on CHOs in tennis has been limited to one match or equivalent, there is a need to focus on concentrations of blood glucose and muscle glycogen in tennis players during multiple matches in a single day and/or multi‐day tournaments.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Bergstrom J, Hermansen L, Hultman E.et al Diet, muscle glycogen and physical performance. Acta Physiol Scand 196771140–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coyle E F. Physiological determinants of endurance exercise performance. J Sci Med Sport 19992181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovacs M S. A comparison of work/rest intervals in men's professional tennis. Medicine and Science in Tennis 2004910–11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Convertino V, Armstrong L E, Coyle E F.et al American College of Sports Medicine position stand: exercise and fluid replacement. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28: i–vii, [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Casa D J, Armstrong L E, Hillman S K.et al National athletic trainer's association position statement: fluid replacement for athletes. J Athl Train 200035212–224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coggan A R, Coyle E F. Carbohydrate ingestion during prolonged exercise: effects on metabolism and performance. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 1991191–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas D E, Brotherhood J R, Brand J C. Carbohydrate feeding before exercise. Int J Sports Med 199112180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Short K R, Sheffield‐Moore M, Costill D L. Glycemic insulinemic responses to multiple preexercise carbohydrate feedings. Int J Sports Nutr 19977128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fink W J, Costill D L, Van Handel P J. Leg muscle metabolism during exercise in the heat and cold. Eur J Appl Physiol 197534183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergeron M F, Maresh C M, Kraemer W J.et al Tennis: a physiological profile during match play. Int J Sport Med 199112474–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell J B, Cole K J, Granjean P W.et al The effect of a carbohydrate beverage on tennis performance and fluid balance during prolonged tennis play. Journal of Applied Sport Science Research 1992696–102. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke E R, Ekblom B. Influence of fluid ingestion and dehydration on precision and endurance performance in tennis. Athletic Trainer 198217275–277. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costill D L, Hargreaves M. Carbohydrate nutrition and fatigue. Sports Med 19921386–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrauti A, Weber K, Struder H K. Metabolic and ergogenic effects of carbohydrate and caffeine beverages in tennis. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 199737258–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrauti A, Pluim B M, Busch T.et al Blood glucose responses and incidence of hypoglycaemia in elite tennis under practice and tournament conditions. J Sci Med Sport 2003628–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horowitz J P, Coyle E F. Metabolic responses to preexercise meals containing various carbohydrates and fat. Am J Clin Nutr 199358235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costill D L, Miller J M. Nutrition for endurance sport: carbohydrate and fluid balance. Int J Sports Med 198012–14. [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacLaren D P M. Nutrition for racket sports. In: Lees A, Maynard I, Hughes M, Reilly T, eds. Science and racket sports II. London: E & FN Spon, 199843–51.

- 19.Ferrauti A, Neumann K, Weber K.et al Urine catecholamine concentrations and psychophysical stress in elite tennis under practice and tournament conditions. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 200141269–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coyle E F, Coggan A R, Hemmert M K.et al Muscle glycogen utilization during prolonged strenuous exercise when fed carbohydrates. J Appl Physiol 198661165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coyle E F, Hagberg J M, Hurley B F.et al Carbohydrate feeding during prolonged strenuous exercise can delay fatigue. J Appl Physiol 198355230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brun J F, Dumortier M, Fedou C.et al Exercise hypoglycemia in nondiabetic subjects. Diabetes Metab 20012792–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christmass M A, Richmond S E, Cable N T.et al A metabolic characterisation of single tennis. In: Reilly T, Hughes M, Lees A, eds. Science and racket sports. London: E & FN Spon, 19953–9.

- 24.Therminarias A, Dansou P, Chirpaz‐Oddou M F.et al Hormonal and metabolic changes during a strenuous tennis match: effect of ageing. Int J Sports Med 19911210–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellliott B, Dawson B, Pyke F. The energetics of singles tennis. J Hum Mov Stud 19851111–20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernardi M, De Vito G, Falvo M E.et al Cardiorespiratory adjustment in middle‐level tennis players: are long term cardiovascular adjustments possible? In: Lees A, Maynard I, Hughes M, Reilly T, eds. Science and racket sports II. London: E & FN Spon, 199820–26.

- 27.Costill D L. Carbohydrates for exercise: dietary demands for optimal performance. Int J Sports Med 198891–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coyle E F, Hagberg J M, Hurley B F.et al Carbohydrate feeding during prolonged strenuous exercise can delay fatigue. J Appl Physiol 198355230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hargreaves M, Costill D L, Coggan A R.et al Effect of carbohydrate feeding on muscle glycogen utilization and exercise performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 198416219–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vergauwen L, Brouns F, Hespel P. Carbohydrate supplementation improves stroke performance in tennis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998301289–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray R, Eddy D E, Murray T W.et al The effect of fluid and carbohydrate feedings during intermittent cycling exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 198719597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vergauwen L, Spaepen A J, Lefevre J.et al Evaluation of stroke performance in tennis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998301281–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coyle E F. Fluid and fuel intake during exercise. J Sport Sci 20042239–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrauti A, Weber K. Metabolic responses and performance after caffeine ingestion. In: Lees A, Maynard I, Hughes M, Reilly T, eds. Science and racket sports II. London: E & FN Spon, 1998, 60–7

- 35.Powers S K, Dodd S. Caffeine and endurance performance. Sports Med 19852165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ivy J L, Costill D L, Fink W J.et al Influence of caffeine and carbohydrate feedings on endurance performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1979116–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costill D L, Dalsky G, Fink W J. Effects of caffeine ingestion on metabolism and exercise performance. Med Sci Sports 197810155–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivy J L, Costill D L, Fink W J.et al Influence of caffeine and carbohydrate feedings on endurance performance. Med Sci Sports 1979116–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis S N, Galasetti P, Wasserman D H.et al Effects of antecedent of hypoglycaemia on subsequent counterregulatory responses to exercise. Diabetes 20004973–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burke L M, Cox G R, Culmmings N K. Guidelines for daily carbohydrate intake: do athletes achieve them? Sports Med 200131267–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagenmakers A J, Brouns F, Saris W H.et al Oxidation rates of orally ingested carbohydrates during prolonged exercise in men. J Appl Physiol 1993752774–2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray R, Paul G L, Seifert J G.et al The effects of glucose, fructose, and sucrose ingestion during exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 198921275–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coleman E. Update on carbohydrate: solid versus liquid. Int J Sport Nutr 1994480–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Febbraio M A, Murton P, Selig S.et al Effect of CHO ingestion on exercise metabolism and performance in different ambient temperatures. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996281380–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galloway S, Maughan R. The effects of substrate and fluid provision on thermoregulatory and metabolic responses to prolonged exercise in a hot environment. J Sport Sci 200018339–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jung A P, Bishop P A, Al‐Nawwas A.et al Influence of hydration and electrolyte supplementation on incidence and time to onset of exercise‐associated muscle cramps. J Athl Train 20054071–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hargreaves M, Dillo P, Angus D.et al Effect of fluid ingestion on muscle metabolism during prolonged exercise. J Appl Physiol 199680363–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonen A, Ness G W, Belcastro A N.et al Mild exercise impedes glycogen repletion in muscle. J Appl Physiol 1985581622–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ivy J L, Katz A L, Cutler C L.et al Muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise: effect of time of carbohydrate ingestion. J Appl Physiol 1988641480–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ploug T, Galbo H, Vinten J.et al Kinetics of glucose transport in rat muscle: effects of insulin and contractions. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 1987253E12–E20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burke L M, Collier G R, Hargreaves M. Muscle glycogen storage after prolonged exercise: effect of glycaemic index of carbohydrate feedings. J Appl Physiol 1993751019–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ivy J L, Lee M C, Brozinick J T.et al Muscle glycogen storage after different mounts of carbohydrate ingestion. Am J Physiol 1988652018–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ivy J L, Goforth H W, Jr, Damon B M.et al Early postexercise muscle glycogen recovery is enhanced with a carbohydrate‐protein supplement. J Appl Physiol 2002931337–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Loon L J, Saris W H, Kruijshoop M.et al Maximizing postexercise muscle glycogen synthesis: carbohydrate supplementation and the application of amino acid or protein hydrolysate mixtures. Am J Clin Nutr 200072106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]