Abstract

Objective

To determine the relationship between physicians’ communication behaviors and patients’ overall satisfaction with hospital care using a novel instrumental variable to address possible confounding of this association by patient attributes.

Data Sources/Study Setting

Administrative records and postdischarge survey data were obtained from patients discharged from the General Medicine service at an urban tertiary-care academic hospital between July 1, 1997 and June 30, 2000. Administrative data included comorbidities, demographic data, and payer status. In the discharge survey, patients rated their attending physician on four communication behaviors, other aspects of their hospital stay, and their overall hospital care.

Study Design

The primary outcome was patients’ ratings of their overall satisfaction with hospital care, and the primary independent variable was patients’ ratings of their physicians’ communication behaviors. To remove possible confounding of the association between patient ratings of physician communication and overall satisfaction by other patient-specific attributes, we created an instrumental variable (IV) in a two-stage linear regression. The IV was the mean of the communication ratings given to each physician by the other patients cared for by that physician.

Principle Findings/Conclusions

Three thousand one hundred and twenty-three patients were included in the analysis. In the ordinary least squares regression, there was a significant positive relationship between overall satisfaction and overall ratings of attendings’ communication behaviors, with an increase in overall satisfaction of 0.58 points on a 5-point scale for each 1-point increase in overall attendings’ communication behaviors, p<.001. This relationship was maintained but attenuated in the IV regression, with a coefficient of 0.40, p=.046. Although we find that the relationship between patient communication ratings and overall patient satisfaction may be confounded by patient-level factors, we nevertheless continue to find evidence of a statistically significant and sizable relationship between physicians’ communication behaviors and overall patient satisfaction after controlling for such factors.

Keywords: Physician–patient relations, quality of health care, inpatients, instrumental variables, patient–physician communication

Patients’ satisfaction with their hospital care is important to payers, hospital administrators, physicians, and patients. It is important because it captures the patients’ experience of health care outside of direct effects on health and acknowledges the role of the patient as partner in health care, and as such reflects the patient-centeredness of care (Institute of Medicine 2001). It also offers insight into patients’ perceptions of interpersonal relations and amenities. In addition, it is a goal toward which considerable resources are directed (Dranove et al. 1999). Physicians’ communication behaviors are important contributors to patient satisfaction in the outpatient setting (Stewart 1995;Williams, Weinman, and Dale 1998). In the inpatient setting, several studies have indicated that the quality of aspects of communication with physicians is important to hospitalized patients (Rubin 1990;Hall, Elliott, and Stiles 1993;Moller-Leimkuhler et al. 2002).

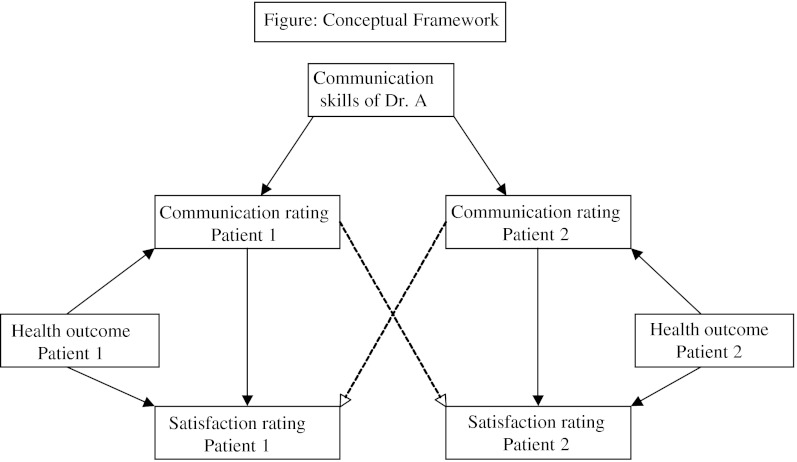

Determining whether physicians’ communication behaviors have a direct effect on patient satisfaction ratings is not straightforward, however, because their association may be confounded in several ways. For example, an association between ratings of communication behaviors and overall satisfaction could reflect reverse causation in which patients who are more satisfied with their care are also more likely to rate their physicians’ communication behaviors highly. In addition, patients who have heard good news, or who have had a good health outcome, may give high ratings for the physician's communication behaviors and report greater satisfaction, producing an association not due to any effects of communication on overall satisfaction. Similarly, patients who are generally unhappy or more difficult to please might give lower ratings to both their physician's communication behaviors and their satisfaction, again producing a spurious association. We present a diagram below that illustrates this concept (see Figure 1). To address such confounding of the association of communication and overall satisfaction by patient factors, we need ratings of communication that are independent of individual patient factors that may also affect overall satisfaction.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework.

Notes: The essence of this framework is that patient satisfaction ratings may be determined by both physician attributes and by patient outcomes. In particular, we think that outcomes for patient (good or poor) might result in corresponding (good or poor) ratings by a patient of both physician communication and overall satisfaction. As a result, observed associations between patients’ ratings of physician communication and their satisfaction with care could be biased by this association. These are shown on the right and left sides of Figure 1 by the solid arrows from the outcomes for each patient to their ratings of their doctor's communication and their rating of satisfaction with overall care. Our conceptual model also assumes that bad outcomes for a given patients will not alter the communication ratings of other patients. Therefore, our conceptual model implies that we can eliminate this “outcome-induced” bias in the association between communication ratings and satisfaction by using the communication ratings of other patients to rate the communication of physicians. This can be seen in Figure 1 because the causal pathway from poor doctor communication to poor satisfaction with care for Patient 1 that is mediated through the communications ratings of Patient 2 is not affected by the outcomes of Patient 1. The same is true of course for the ratings of patients’ ratings of communication behaviors.

Instrumental variable (IV) analysis is one means of addressing these issues of confounding. IV is best known in health service research as a useful tool when comparisons between two or more treatment groups are confounded by factors that cannot be completely controlled for, and randomization is not feasible (McClellan and Newhouse 2000). Less widely appreciated is that IV analysis can also be used to avoid bias that can arise when an explanatory variable of interest is measured with error (Hausman 2001), as patient ratings of physician communication may be if they are confounded by bad patient outcomes or other unmeasured patient-level attributes (Hausman et al. 1991).

The data for our study come from the University of Chicago Hospital Internal Medicine inpatient service, which since 1997 has systematically collected data to measure the financial, educational, and patient care effects of different strategies of organizing care. Part of this data collection effort includes a 1-month postdischarge survey that asks patients to rate their physicians’ communication behaviors and their satisfaction with their care in the hospital. Our goal in this study was to determine whether there is an association between communication and overall satisfaction ratings. To address the issues of reverse causation and other patient-specific confounders of this relationship, we designed a novel measure of the communication behaviors of a patient's physician constructed to be independent of patient-specific factors that could affect overall satisfaction so that it could serve as an instrumental variable in studying the effects of communication on overall satisfaction. We constructed this instrumental variable using the average ratings of the physician's communication behaviors provided by other patients cared for by that physician. The motivation for this is that patient-specific factors affecting attending communications ratings (such as patient outcomes) could bias patients’ assessments of their attending's communication style, but other patients’ ratings of that attending's communication style would not be confounded in this way. We then tested whether this measure of attending communication based on the ratings of other patients was associated with improved patient satisfaction.

Methods

Study Subjects

Patients were eligible if they were admitted to the University of Chicago Hospital's General Internal Medicine service between July 1, 1997, and June 30, 2000, and were able to give consent to participate. Patients were excluded if they were discharged before they could be approached by research staff, had been admitted to our hospital and participated in the study within the past 60 days, or were unable to speak English, or had cognitive difficulties. Patients were assigned to physicians based on day of admission according to a predetermined call schedule. Physicians were faculty of the Department of Medicine of the University of Chicago.

Data Collection

We surveyed patients in person while they were in the hospital and by telephone once month after they were discharged. Trained research assistants administered the surveys. The in-hospital survey consisted of approximately 30 questions and took 15 minutes to complete. The 1-month follow-up survey consisted of 20 questions and took 10 minutes to complete. Phone call attempts were made at least eight times at different times of day until patients were reached or it was determined that they were unreachable.

Outcome Variables

We used a single question from the Picker inpatient questionnaire during the 1-month follow-up survey to measure our dependent variable, patients’ ratings of their hospital care: “Overall, how would you rate the care you received at the hospital?” on a 5-point scale: Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair, Poor. To measure our independent variable, patients’ ratings of their attending physicians’ communication behaviors, we asked each patient during the 1-month follow-up survey to rate his or her attending physician using questions drawn from the American Board of Internal Medicine Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (ABIM PSQ) (American Board of Internal Medicine 1988). These questions asked patients to rate their doctors according to the following criteria designed to capture elements of effective communication:

Treating you like you are on the same level; never talking down to you or treating you like a child.

Letting you tell your story; listening carefully; asking thoughtful questions; not interrupting while you are talking.

Discussing options with you; asking your opinion; offering choices and letting you help decide what to do; asking what you think before telling you what to do.

Encouraging you to ask questions; answering them clearly; never avoiding questions or lecturing you.

Patients rated these elements on a five-point scale from Excellent to Poor.

Control Variables

Nursing care, report of pain while in the hospital, level of health, race, age, gender, socioeconomic level have all been shown to affect patient's ratings of the care they receive in the hospital (Hall, Elliott, and Stiles 1993). To control for these variables, we asked patients during the 1-month follow-up survey to rate whether they had confidence and trust in the nurses treating them on a three-point scale: Yes, always; Yes, sometimes; No, never. We asked them whether they had pain in the hospital, using a single item from the Picker inpatient questionnaire. In the in-hospital survey we gathered patient-reported level of education on a 3-point scale: less than high school, some high school, high school graduate or more, and abstracted their ratings of their physical health at the time of hospitalization using the physical component subscale of the SF-12 (Ware, Kosinski, and Keller 1995). We measured patients’ comorbidities using a claims-based Charlson index with a one-year look-back (Charlson et al. 1987;Deyo, Cherkin, and Ciol 1992;Romano, Roos, and Jollis 1993). Hospital administrative data provided information regarding age, race, gender, and payer status, using an activity-based accounting system produced by Transitions Systems Incorporated.

Analytic Approach

To evaluate the effect of physicians’ communication behaviors on patient ratings of satisfaction, we initially compared patients’ sociodemographic and health data using chi-square tests for dichotomous data and the student's t-test for continuous data. We devised a summary physician communication rating (PCR) by adding each patient's ratings of each of his or her attending's four communication behaviors, and dividing this number by 4.

To determine the relationship between patient satisfaction and the PCR, we constructed an ordinary least squares regression model that controlled for patients’ confidence in nurses, presence of pain while in the hospital, physical component subscale score of the SF-12, level of education, race (black or white), sex, age, and payer status. To control for the effect of team members (since patients might confuse one physician for another on the team), we included indicator variables for the intern assigned to the patient at the time of admission. To address clustering of patients by attending physicians, we did statistical tests based on robust standard errors, with cluster correction for the attending physician. To control for secular trends, we included indicator variables for the month of admission.

Instrumental Variable

To remove possible effects of a patient's overall satisfaction with care or other patient-specific attributes on his or her ratings of communication, we created a measure of the physicians’ communication behaviors that was independent of that patient's own ratings or other attributes. To do this we constructed a variable that averaged the communication ratings of all of each physician's patients except the patient in question. We then used this as an instrumental variable (IV) in a two-stage least squares regression. To assess the appropriateness of the IV, we used linear regression to determine the strength of the relationship between the IV and the independent variable (the PCR), controlling for the full set of covariates in our final analysis (Newhouse and McClellan 1998).

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA, version 7, for the Macintosh.

Results

Recruitment

Between July 1, 1997, and June 30, 2000, 11,191 patients were admitted or transferred to the general medicine service. Of these, 2,486 (22 percent) were discharged before they could be interviewed or could not participate because of mental or physical infirmity, and 60 (0.5 percent) died. We excluded 1,451 (13 percent) patients who had been admitted and participated in the study in the past 60 days. Five hundred and ninety-eight (5 percent) refused to participate. Of the 6,596 (67 percent of eligible patients) who were enrolled and completed inpatient surveys, 1-month follow-up surveys were completed for 4,916 (75 percent). Of those who were not included in the follow-up survey, 957 (15 percent) could not be contacted after at least eight phone attempts, 470 (7 percent) died within 30 days, and 250 (4 percent) refused to participate. In this analysis, we excluded 1,146 proxy respondents (17 percent of the 4,916 follow-up interviews) who answered questions on behalf of patients who could not consent based on scoring below a 17 on the Roccaforte telephone version of the mini-mental status exam, as we felt that proxies might not give valid ratings of satisfaction with care and communication behaviors. Our final sample consisted of 3,770 individuals. Of those, 3,015 (80 percent) were unique observations. Data analysis was performed on 3,123 individuals without missing data.

Participant Characteristics

Characteristics of patients who participated in the 1-month follow-up survey are presented in Table 1. Patients who were included in the inpatient survey had fewer comorbidities (2.2 versus 2.4) and were younger (mean age 56.8 versus 59.9) than those who were not (p<.001 for both) and did not differ with respect to gender, race, or insurance status. Patients who participated in the 1-month follow-up survey were more likely than those who did not participate to be female (75.4 versus 71.8 percent, p=.004), and less likely to have health insurance through Medicaid (71.6 versus 75.3 percent, p=.007) and be African American (72.7 versus 80.2 percent, p<.001), and did not differ significantly with respect to their age, level of education, comorbidities, or physical component subscale score of the SF-12. There were 69 attendings physicians in the final sample. The attending physicians had a mean age of 38 years (range, 29–62), had spent on average 6 years as attending physicians (range, 0–28), and spent on average 51 percent of their time in patient care (range, 10–95 percent). The minimum number of patients per physician was 3; 10th percentile 10; median 35; 90th percentile 79; and maximum 277.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Participating in 1-Month Follow-Up Survey (n=3123)*

| Age, mean (range, SD), years | 55 (19–101, 18.6) |

| Female | 1,985 (63.6) |

| Race | |

| African American | 2,522 (80.8) |

| Asian | 32 (1.0) |

| Hispanic | 45 (1.4) |

| White | 502 (16.1) |

| Other | 22 (0.7) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school graduate | 906 (29.0) |

| High school graduate | 859 (27.5) |

| Greater than high school education | 1,358 (43.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 1,034 (33) |

| Divorced | 529 (16.9) |

| Widowed | 621 (19.9) |

| Single | 939 (30.1) |

| Insurance | |

| Medicare | 1,296 (41.5) |

| Medicaid | 856 (27.4) |

| Self-pay | 55 (1.7) |

| Private | 916 (29.3) |

| Charlson comorbidity score, mean (range, SD) | 2.1 (0–17, 2.4) |

| Physical component of SF-12, mean (range, SD) | 38.4 (10.3–67.8, 12.6) |

* Unless otherwise indicated, data are reported as number (percentage) of patients.

Attending Physicians’ Communication Behaviors

The distribution of patients’ ratings of each of the communication behaviors is reported in Table 2. The median rating for all of the behaviors was “very good.” Only 33 percent of patients rated their attending physicians’ communication behaviors as “excellent” on all four behaviors; 12 percent gave ratings that corresponded to “fair” or “poor” on all four behaviors.

Table 2.

Patients’ Ratings of Attending Physician's Communication Behaviors

| Behavior | Percent of Patients Giving Each Rating | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | Very Good | Good | Fair | Poor | |

| Treated patient on the same level | 48.4 | 25.4 | 18.4 | 5.1 | 2.7 |

| Encouraged patient to ask questions | 44.4 | 24.1 | 20.9 | 5.4 | 5.2 |

| Let patient tell his or her story without interrupting | 47.8 | 24.9 | 19.9 | 4.4 | 3.1 |

| Discussed options with the patient | 41.8 | 23.6 | 21.4 | 6.5 | 6.7 |

Relationship of Communication Behaviors Ratings to Satisfaction

Because of missing data, only 3,123 patients were included in the regression analyses. (We chose not to impute values for our primary predictor or outcome variables as we felt that neither assignation of mean values or imputation based on other characteristics would capture meaningful information regarding patients’ perceptions of their physicians’ communication behaviors or overall satisfaction with care in the hospital.) In bivariate analysis, a 1-point increase in the summary physician communication rating, corresponding to an increase of one point in a patient's ratings of each of the four communication behaviors, was associated with an average increase of 0.62 points in satisfaction ratings (95 percent confidence interval 0.59–0.65, p<.001). After adjusting for confidence in nurses, pain while in hospital, physical component subscale score of the SF-12, Charlson comorbidity score, demographic data, intern who admitted the patient, month of admission, and clustering within physician, a 1-point increment in the summary physician communication rating was associated with an average increase of 0.58 points in overall satisfaction ratings (95 percent CI 0.55–0.61, p<.001). When using our instrumental variable in a two-stage least squares regression, a 1-point increment in the physician communication rating was associated with an average increase of 0.40 points in satisfaction ratings (95 percent CI 0.01–0.79, p=.046). The results of the ordinary least squares (OLS) and IV regressions are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Instrumental Variable (IV) Regressions

| Variable | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS Regression | IV Regression | |||

| Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | |

| Attendings’ total communication score | 0.58 | <.001 | 0.40 | .046 |

| Trust in nurses | 0.36 | <.001 | 0.44 | <.001 |

| Report of pain while in the hospital | −0.04 | .19 | −0.05 | .10 |

| Level of education (<HS, HS grad, >HS) | −0.02 | .34 | −0.008 | .71 |

| Charlson coefficient | −0.004 | .55 | −0.004 | .43 |

| Physical component of SF-12 | 0.0006 | .65 | 0.0008 | .65 |

| Age (years) | 0.0003 | .76 | 0.0002 | .87 |

| African-American race (0=no, 1=yes) | 0.058 | .13 | 0.04 | .325 |

| Gender (0=male, 1=female) | −0.02 | .58 | −0.02 | .60 |

| Payer status | ||||

| Medicaid (0=no, 1=yes) | 0.05 | .21 | 0.04 | .27 |

| No payer (0=no, 1=yes) | 0.08 | .42 | 0.08 | .44 |

Adequacy of the IV

The instrument is likely to be exogenous to individual patient determinants of overall satisfaction because it represents what all other patients say about the attending physician's communication behaviors except the patient in question. It is possible that a patient might know what other patients thought of his or her attending's communication behaviors, and use this as a metric for rating his or her hospital stay, but this is unlikely to be common. Another potential concern with instrumental variables is that weak instrumental variables (F<10) have been shown to potentially bias the results of IV regression (Staiger and Stock 1994). When the predictor variable (the PCR) is regressed on the instrument and other covariates in our final model, it results in a partial F statistic of 39, suggesting that our IV is sufficiently strong to avoid this potential bias.

Discussion

Our study showed considerable variation in patients’ perceptions of their physicians’ communication skills in the hospital. These ratings were related to their overall satisfaction, even controlling for attributes of patients and staff known to affect patient satisfaction. The size of the coefficient, 0.40–0.68 points on a 5-point scale, is meaningful in quality of care ratings. For example, small differences, as little as 0.1 points in a 5-point scale, in patients’ quality of care and satisfaction ratings have been associated with changes in patient behavior and health outcomes such as hypertensive control, adherence to medications, and returning to the same physician for care (Rubin et al. 1993;Harris et al. 1995;Vermeire et al. 2001). That only 33 percent of physicians in our sample were rated “excellent” on all four communication behaviors suggests that there may be significant room for improvement in physicians’ communication behaviors in the hospital. This may be an important area for hospitals to focus on in their efforts to improve their quality of care.

Other studies have established that physician communication behaviors, such as lack of physician dominance, physician questions about psychosocial issues, information giving, positive affect and friendliness, discussing options, and encouraging patients to ask questions, are associated with patient satisfaction in the outpatient setting (Stewart 1995;Williams, Weinman, and Dale 1998). Some other studies have shown that physicians’ technical and communication behaviors are important to hospitalized patients (Matthews and Feinstein 1989;Cleary et al. 1991;Minnick et al. 1997). Our study's findings are consistent with those that have found significant association between elements of inpatient physicians’ communication behaviors, such as treatment with respect and dignity, respect for preferences, and involving patients in decision making (Jenkinson et al. 2002;Moller-Leimkuhler et al. 2002;Joffe et al. 2003;Gesell, Clark, and Williams 2004), and satisfaction with health care. Our data focus in particular on the relationship between the patient and the physician, not the overall hospital experience, and focus on a patient population than is usually not well studied.

What do the results of the instrumental variable regression indicate? Because of the way that the variable was constructed, it removes the possibility that (1) a patient's own tendencies to give high or low ratings or (2) that patient's good or bad hospital experiences are affecting both their ratings of the physician's communication behaviors and their ratings of their care in the hospital, either of which could create a spurious association between the two. While these data cannot determine whether physicians’ communication behaviors causally influence patients’ care ratings, they do suggest that the association of these variables in the instrumental variables analysis is not explained by other patient-level factors such as bad outcomes or an individual patient's general tendency towards satisfaction or dissatisfaction. It should be noted that one limitation of the IV analysis is that the estimated effects are estimated with significantly less precision that in the OLS analysis. Given the potential concern about bias in the OLS estimates, however, we feel that this tradeoff is a worthwhile one that suggests that the use of such IV estimators to address measurement error in situation such as this may be useful in some instances.

This study has certain limitations. It cannot determine whether other physician characteristics, such as technical behavior, may have influenced patients’ ratings of both the physician's communication behaviors and their ratings of the care they received in the hospital. Patient satisfaction surveys that request ratings are inherently confounded by expectations, and use of “experience” or “experience-like” questions, such as “would you recommend this hospital to a friend or relative” might minimize this confounding.

In addition, many individuals (over 70 percent of those admitted in the three year period) were excluded from the study by limitations of recruitment and follow-up, and by analysis because of missing values. Individuals not recruited and not followed up differed significantly from those included in the analysis in age, gender, and level of health, all characteristics that have been shown to be significantly related to satisfaction and communication ratings. The bias in the sample, that patients not followed up in the one-month survey were more likely to have public assistance for medical coverage and to be male and African American, may artifactually raise our estimation of patient's ratings of their attending physicians’ communication behaviors, given that the last two characteristics are associated with lower ratings of physician communication behaviors (Hall, Elliott, and Stiles 1993). However, the response rate in our sample of eligible discharged patients of 75 percent is similar to the typical response rates for hospital satisfaction surveys (Sitzia and Wood 1998). Thus, our data provide a representation of the population of patients among whom determinants of satisfaction might be a concern that is at least as broad as most studies in this area. Second, even if the results of our study are relevant only among subjects who respond to patient satisfaction surveys, this is an interesting group to understand to the extent that the type of bias our analysis can adjust for (e.g., bad outcomes affect ratings) is one that we would want to control for in analyses of answers from these respondents. Finally, the sample was drawn from one service at one hospital, which may limit its generalizability. It does, however, focus on an urban inner-city population, which has not been well represented in previous studies of patient–physician communication and quality of care.

Implications

These results support the hypothesis that physicians’ communication behaviors are associated with overall ratings of satisfaction. This suggests that simple changes that physicians can make when talking with patients, such as asking patients for their opinions, letting them tell their stories, and encouraging them to ask questions, may have a substantial impact on patients’ quality of care ratings. While many patients find that their physicians on average do a “very good” job in these skills, there is substantial room for improvement, and these findings may underestimate the deficit in physicians’ skills. Continuing efforts to collect data on patient ratings of physician communication behaviors and satisfaction, as will soon be available from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, will allow further study of the relationship between the two. It will also become increasingly important that we continue to advance our understanding of these measures and their association with each other. Furthermore, practice environments need to be shaped so that they allow for the development of good patient–physician relationships.

These results also indicate that there is significant confounding in this relationship that likely has not been taken into account in previous work in this area. The use of instrumental variables constructed using the assessments of other patients may be useful for addressing other potential associations of physician characteristics with outcomes in situations in which analyses using ratings from a single patient could produce spurious associations due to confounding by patient-level factors. More generally, the IV approach we describe here could be useful in other areas of inquiry in which reports from multiple individuals affected by some factor are available and the potential for confounding of those individuals’ reports by individual-specific factors is a concern.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: Grant support for this study was provided by the University of Chicago Hospitals, Chicago, IL; the Charles E. Culpeper Foundation, New York, NY; the National Institute of Aging, Bethesda, MD; and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, NJ. Dr. Clever was a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar at the time the research was done. Earlier versions of this work were presented at the 25th Annual Society for General Internal Medicine national meeting, Atlanta, GA, April 2002, and at the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars meeting, Fort Lauderdale, FL, November 2002.

Disclosures: None.

Supplementary material

The following supplementary material for this article is available online:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix

This material is available as part of the online article from http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00849.x (this link will take you to the article abstract).

Please note: Blackwell Publishing is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supplementary materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- American Board of Internal Medicine. Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire: Guide to Awareness and Evaluation of Humanistic Qualities in the Internist. Philadelphia: American Board of Internal Medicine; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A New Method of Classifying Prognostic Comorbidity in Longitudinal Studies: Development and Validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary PD, Edgman-Levitan S, Roberts M, Moloney TW, McMullen W, Walker JD, Delbanco TL. Patients Evaluate Their Hospital Care: A National Survey. Health Affairs (Millwood) 1991;10(4):254–67. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.10.4.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a Clinical Comorbidity Index for Use with ICD-9-CM Administrative Databases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dranove D, Reynolds KS, Gillies RR, Shortell SS, Rademaker AW, Huang CF. The Cost of Efforts to Improve Quality. Medical Care. 1999;37(10):1084–7. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199910000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesell SB, Clark PA, Williams A. Inpatient Heart Failure Treatment from the Patient's Perspective. Quality Management in Health Care. 2004;13(3):154–65. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200407000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MC, Elliott KM, Stiles GW. Hospital Patient Satisfaction: Correlates, Dimensionality, and Determinants. Journal of Hospital Marketing. 1993;7(2):77–90. doi: 10.1300/J043v07n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LE, Luft FC, Rudy DW, Tierney WM. Correlates of Health Care Satisfaction in Inner-City Patients with Hypertension and Chronic Renal Insufficiency. Social Science Medicine. 1995;41(12):1639–45. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00073-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman J. Mismeasured Variables in Econometric Analysis: Problems from the Right and Problems from the Left. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2001;15(4):57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hausman J, Newey W, Ichimura H, Powell J. Measurement Errors in Polynomial Regression Models. Journal of Econometrics. 1991;50:273–95. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S, Richards N, Chandola T. Patients’ Experiences and Satisfaction with Health Care: Results of a Questionnaire Study of Specific Aspects of Care. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2002;11(4):335–9. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.4.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe S, Manocchia M, Weeks JC, Cleary PD. What Do Patients Value in Their Hospital Care? An Empirical Perspective on Autonomy Centred Bioethics. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2003;29(2):103–8. doi: 10.1136/jme.29.2.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DA, Feinstein AR. A New Instrument for Patients’ Ratings of Physician Performance in the Hospital Setting. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1989;4(1):14–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02596484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan MB, Newhouse JP. Overview of the Special Supplement Issue. Health Services Research. 2000;35(5, part 2):1061–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnick AF, Roberts MJ, Young WB, Kleinpell RM, Marcantonio RJ. What Influences Patients’ Reports of Three Aspects of Hospital Services? Medical Care. 1997;35(4):399–409. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199704000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller-Leimkuhler AM, Dunkel R, Muller P, Pukies G, de Fazio S, Lehmann E. Is Patient Satisfaction a Unidimensional Construct? Factor Analysis of the Munich Patient Satisfaction Scale (MPSS-24) European Archive of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2002;252(1):19–23. doi: 10.1007/s004060200003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse JP, McClellan M. Econometrics in Outcomes Research: The Use of Instrumental Variables. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:17–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a Clinical Comorbidity Index for Use with ICD-9-CM Administrative Data: Differing Perspectives. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1993;46(10):1075–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. discussion 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin HR. Patient Evaluations of Hospital Care. A Review of the Literature. Medical Care. 1990;28(9 Suppl):S3–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199009001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin HR, Gandek B, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, McHorney CA, Ware JE., Jr Patients’ Ratings of Outpatient Visits in Different Practice Settings. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;270(7):835–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitzia J, Wood N. Response Rate in Patient Satisfaction Research: An Analysis of 210 Published Studies. International Journal of Quality Health Care. 1998;10(4):311–7. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/10.4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger D, Stock JH. Instrumental Variable Regression with Weak Instruments. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart MA. Effective Physician–Patient Communication and Health Outcomes: A Review. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1995;152(9):1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J. Patient Adherence to Treatment: Three Decades of Research. A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Clinical Pharmaceutical and Therapeutics. 2001;26(5):331–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. SF-12: How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Williams S, Weinman J, Dale J. Doctor–Patient Communication and Patient Satisfaction: A Review. Family Practice. 1998;15(5):480–92. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.5.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.