Abstract

Background:

Whereas animal models of sepsis demonstrate survival benefits for the pro-estrus state, human observational studies have failed to demonstrate a consistent survival advantage among female patients. Estrogen biosynthesis differs substantially in primate and non-primate animals, and estrogens have diverse immunologic actions. Estrogen concentrations are elevated in response to critical illness and injury (regardless of sex), and elevated concentrations of serum estradiol are associated with a higher mortality rate. Our objective was to determine the predictive ability and test characteristics of the serum estradiol concentration at 48 h in critically ill patients.

Methods:

A prospective cohort study of surgical and trauma adult intensive care unit patients at two academic tertiary-care centers. Sex hormones (estradiol, progesterone, testosterone, prolactin, and dehydroepiandrosterone) and cytokines were assayed at 48 h, and the 28-day all-cause mortality rate was assessed.

Results:

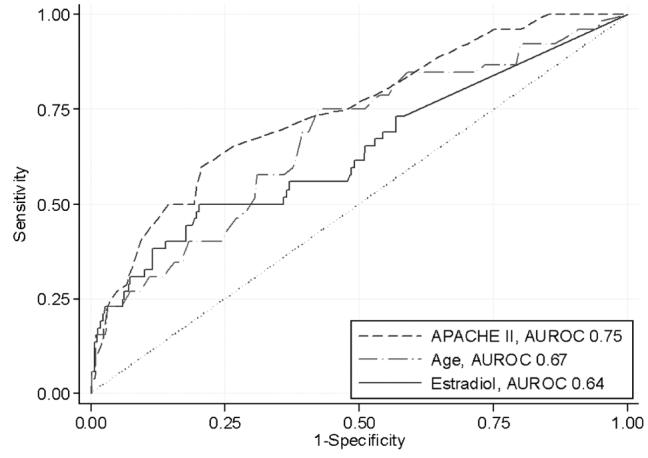

There was no difference in mortality rates between the sexes (survivors being male in 75.2% of cases vs. 76.0% in non-survivors; p = 0.43). The serum estradiol concentration was significantly elevated in non-survivors regardless of sex (median 18.7 pg/mL [interquartile range {IRQ} 9.99–43.6] in survivors and 40.7 pg/mL [IQR 9.99–94.8] in non-survivors; p < 0.001). The area under the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve for serum estradiol was 0.64 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.55, 0.72). The parameter with the largest ROC curve was the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score (0.75; 95% CI 0.68, 0.82). A serum estradiol cut-point of 50 pg/mL was 48% sensitive and 80% specific in predicting death and classified the outcome of 76% of patients correctly.

Conclusions:

Serum estradiol concentration is a valuable prognostic tool and potential contributor to adverse outcomes of critically ill or injured surgical patients.

Death in the intensive care unit (ICU) from sepsis or multiple organ dysfunction syndrome is a complex event dependent on both host and pathogen; perhaps no injury-related factors are more important than a patient's immunologic and inflammatory response to illness or injury. Whereas the magnitude of the primary insult is largely responsible for the degree of these responses, demographic, genetic, and environmental factors undoubtedly impact this response. One factor that has been considered widely to be important in the degree of these responses—and, in turn, outcome—is patient sex. A component of sexual dimorphism (outcomes related to patient sex) has been demonstrated in animal models of trauma and sepsis and believed to be related to the inflammatory and immunologic properties of estrogens. In these models, the pro-estrus state (female animals with ovaries) is associated with an intact immune response and a survival advantage, whereas male and ovariectomized female animals have depressed immune systems and higher mortality rates [1-6].

The relation between sex and outcomes in human beings is not as clear. To date, multiple observational studies have been conducted to determine whether sex plays a role in outcomes after critical illness or injury [7-20]. Most studies have been unable to detect a difference in overall survival [7,8,10,12-15,18]. Some studies show better survival in male patients [9,17], whereas others show better survival in female patients [11,20]

One possible explanation for the apparent absence of sexual dimorphism in human beings is the endocrine response to critical illness. Despite hypothalamic–pituitary suppression, estrogens are elevated in response to stress, regardless of sex. In both men and women and in various settings of critical illness (e.g., sepsis, trauma, myocardial infarction), serum estradiol and estrone concentrations are elevated [6,8,20-24] without a concurrent increase in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) or luteinizing hormone (LH), suggesting a peripheral source of estrogen biosynthesis [22].

Unlike most non-primates, in which estrogen biosynthesis is limited to the brain and gonads, human beings produce estrogens in a number of peripheral tissues where the aromatase enzyme catalyzes the conversion of androgens to estrogens. The primary source of estrogens in both men and post-menopausal women is adipose tissue. Importantly, the aromatase enzyme located in adipose tissue is controlled by a different promoter than the enzyme active in the gonads [25-27]. The gonadal production of estrogens is regulated by the hypothalamicadi–pituitary–gonadal axis via FSH and LH. These hormones stimulate estrogen production via promoter II, which is inhibited by class I cytokines and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. The aromatase enzyme in adipose tissue, on the other hand, is controlled by promoter I.4, which is stimulated by class I cytokines with a requirement for glucocorticoids. Thus, whereas the stress and inflammation in response to critical illness inhibit the central production of estrogens, peripheral biosynthesis is stimulated. This peripheral production of estrogens does not differ between the sexes. Peripheral aromatization has been verified to be the source of estrogens in response to critical illness. In a validated model of the endocrine response to stress (cardiac surgery patients), Spratt et al. demonstrated that increased peripheral aromatization, not decreased metabolism or clearance, is the source of the higher estrogen concentrations [28].

The biologic role of estrogens during critical illness in human beings is unclear, but elevated estradiol has been linked to adverse outcomes in medical ICU patients with severe infection [8]. Although estrogens may simply reflect global illness rather than play a causal role, their potential use as a prognostic biomarker is intriguing. Our objective was to evaluate the test characteristics (sensitivity and specificity) of serum estradiol in predicting in-hospital, 28-day, all-cause death in critically ill and injured surgical patients and to compare its predictive ability with that of other commonly used clinical parameters.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the University of Virginia Health Sciences Center. Patients 18 years of age or older, admitted to the surgical or trauma ICUs of Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, were eligible for enrollment. In order to select a population at high risk of death and morbidity (e.g., organ dysfunction, infectious complications), patients who remained alive and in the ICU for 48 h were eligible for enrollment. This time point served to eliminate those dying of uncontrolled hemorrhage or overwhelming events (e.g., non-survivable traumatic brain injury, severe pulmonary embolism) and those with less severe illness not requiring extended critical care, thus increasing the power of the study while limiting the number required for enrollment. Pregnant women were excluded. A cohort of 417 critically ill or injured surgical patients was enrolled.

Sex, age, body mass index (BMI), date of hospital and ICU admission, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score at 48 h, Acute Physiology Score (APS), Injury Severity Score (ISS), Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS), and in-hospital death were recorded. Illness and injury severity scores were calculated on the basis of the worst physiologic parameters at the time of study entry (48 h after admission). Menopausal status was obtained by patient or family member interview. The post-menopausal state was defined as absence of a menstrual cycle in the previous 12 months or previous bilateral oophorectomy. Patient care was at the discretion of the attending physician according to established critical care protocols in the respective ICUs.

One 10-mL blood sample was collected at study entry for measurement of hormone and cytokine concentrations. Plasma was separated from whole blood and stored at −70°C until analysis. Progesterone, total testosterone, 17β-estradiol (E2), and prolactin assays were performed in the General Clinical Research Center at the University of Virginia Health Sciences Center. Estradiol was measured by kit commercial electroimmunoassay (EIA) utilizing a competitive immunoassay strategy and the alkaline phosphatase/p-Npp chromogenic reaction (Assay Designs, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI; Catalog No. 90108). Total testosterone, prolactin, and progesterone were measured by commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits according to the manufacturer's directions (Alfa Scientific Designs, Inc., San Diego, CA; testosterone assay Catalog No. 700C-081; prolactin assay Catalog No. 30MC-009; progesterone assay Catalog No. 700C-079). Samples also were assayed for interleukins (IL)-1, -2, -4, -6, -8, and -10 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. This was accomplished using a LINCOplex™ custom kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Linco Research, Inc., St. Charles, MO). Human serum (25 microliters from each collection time point on all patients) was run in duplicate on a Luminex100 System® (Miraibio, Inc., Alameda, CA) to determine the concentrations of the cytokines of interest. The Luminex system is an ELISA-based technology allowing multi-analyte detection in a single well. Data reduction was performed with StatLia® (Brendan Technologies, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) and subsequently incorporated into the database.

Normally distributed continuous variables are summarized by reporting the mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) and compared using two-sample t-tests for independent samples. Continuous variables that were not normally distributed are presented by reporting the median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Differences in proportions were compared using a chi-square or Fisher exact test. A computation of the area under the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve was performed for multiple variables at 48 h. The ROC curve describes graphically the sensitivity and specificity of a given diagnostic test. As the area under the ROC curve approaches 1.0, it becomes more accurate; as the area approaches 0.5, it becomes random and of little diagnostic value. The sensitivity, specificity, overall correctness of prediction, and likelihood ratio for various cut-points of estradiol concentration were calculated. A likelihood ratio of 1.0 represents a non-helpful test, whereas a likelihood ratio greater than 1.0 represents the factor by which the pre-test odds of disease are multiplied in order to obtain the post-test odds of disease (in this case, death). Tests for statistical significance were two-sided, with an alpha of 0.05. Stata software version 9.2 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) was used.

All data were maintained in a secure, password-protected database that is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. All patient information was de-identified prior to analysis and reporting.

RESULTS

The overall 28-day mortality rate was 12.0% (50 deaths). The demographics, clinical characteristics, and hormone and cytokine concentrations stratified by outcome are displayed in Table 1. Approximately 75% of the patients were male, a proportion that was similar in survivors and non-survivors. The proportion of trauma victims likewise did not differ between groups. Not surprisingly, survivors were younger and had lower mean APACHE II scores (18.0 [95% CI 16.7, 17.9] vs. 23.3 [95% CI 21.3, 29.9] for non-survivors) and APS (15.8 [95% CI 14.6, 15.7] vs. 19.5 [95% CI 17.7, 21.0] for non-survivors). Survivors and non-survivors did not differ in BMI.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients According to Outcome

| Survivors (n = 367) | Non-survivors (n = 50) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 45.6 (43.8, 47.4) | 57.4 (52.1, 62.8) | <0.001b | |

| Men (no.)(%) | 276 (75.2) | 38 (76.0) | 0.43 | |

| BMIa | 28.3 (27.4, 29.3) | 27.7 (25.6, 29.9) | 0.65b | |

| Trauma victim (%) | 244 (66.5) | 33 (66.0) | 0.95 | |

| Non-trauma cause (%) | 123 (33.5) | 17 (34.0) | 0.81 | |

| Physiology scores | ||||

| APACHE IIa | 17.3 (16.7, 17.9) | 23.1 (21.3, 24.8) | <0.001b | |

| APSa | 15.1 (14.6, 15.7) | 19.4 (17.7, 21.0) | <0.001b | |

| TRISSc | 0.877 (0.589–0.955) | 0.506 (0.290–0.940) | 0.11d | |

| ISSc | 29 (22–38) | 27 (21–41) | 0.64d | |

| MODSa | 8.8 ( 8.5, 9.1) | 10.5 ( 9.6, 11.4) | <0.001b | |

| Serum hormone concentrationsc | ||||

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 18.7 ( 9.99–43.6) | 40.7 ( 9.99–94.8) | <0.002d | |

| Progesterone (ng/mL) | 0.61 ( 0.39–0.87) | 0.67 ( 0.44–1.04) | 0.07d | |

| Prolactin (ng/mL) | 15.4 (10.4–27.2) | 14.6 ( 9.6–35.3) | 0.96d | |

| Testosterone (ng/mL) | 32 (17–42) | 35 (13–52) | 0.78d | |

| DHEA | 51.2 (16.6–99.5) | 49.6 (17.35–126) | 0.66d | |

| White blood cell counta | 17.2 (16.3, 18.1) | 16.9 (14.4, 19.5) | 0.83b | |

| Serum cytokine concentrations (pg/mL)c | ||||

| TNF-α | 7.3 ( 3.2–12.9) | 8.7 ( 4.2–18.2) | 0.18d | |

| IL-1 | 7.9 ( 2.7–28.5) | 5.2 ( 2.7–33.5) | 0.72d | |

| IL-2 | 4.2 ( 2.7–15.6) | 5.0 ( 2.7–19.7) | 0.98d | |

| IL-4 | 24.3 (10.5–67.6) | 55.6 (10.5–105.3) | 0.04d | |

| IL-6 | 99.2 (42.8–214.6) | 173.6 (38.4–627.5) | 0.03d | |

| IL-8 | 24.8 (10.9–49.3) | 59.4 (13.3–120.9) | 0.002d | |

| IL-10 | 39.1 (18.5–105.2) | 78.3 (32.1–184.0) | 0.06d | |

| IL-12 | 8.0 ( 2.9–19.9) | 8.2 ( 3.4–13.7) | 0.035d | |

Shown as mean with 95% confidence interval.

Two-sample t-test.

Shown as median with interquartile range.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; APS = Acute Physiology Score; BMI = Body Mass Index; TRISS = Trauma and Injury Severity Score; ISS = Injury Severity Score; MODS = Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome score; DHEA = dihydroepiandosterone; TNF = tumor necrosis factor; IL = interleukin.

The median serum estradiol concentrations were significantly elevated in non-survivors (18.7 [IQR 9.99–43.6] pg/mL in survivors vs. 40.7 [IQR 9.99–94.8] pg/mL in non-survivors; p < 0.001) regardless of sex. This difference also was observed in the trauma subset (16.4 [IQR 9.99–40.2] pg/mL in survivors and 55.6 [IQR 9.99–92.68] pg/mL in non-survivors; p < 0.001). A difference in estradiol concentrations was not detected in the surgical subset, but with only 123 patients and 17 deaths in this group, this analysis is underpowered. A difference in estradiol concentrations also was present in the male subset (median 15.1 [IQR 9.99–40.6] pg/mL in survivors vs. 40.6 [IQR 9.99–118.3] pg/mL in non-survivors; p < 0.001) and the pre-menopausal subset (median 24.7 [IQR 10.2–49.0] pg/mL in survivors vs. 128.5 [IQR 70.6–186.4] pg/mL in non-survivors; p < 0.001). No difference was detected in the post-menopausal group between survivors and non-survivors (median 25.4 [IQR 9.99–71.5] pg/mL vs. 24.5 [IQR 9.99–63.6] pg/mL; p < 0.86), but again, this group was small (63 patients, 10 deaths). The mortality rate for patients with a serum estradiol concentration less than 45 pg/mL (physiologic range for both men and post-menopausal women) was 8.9% (265/ 291), whereas the mortality rate for patients with concentrations greater than 45 pg/mL was 19.1% (24/102). Serum progesterone, prolactin, testosterone, and dihydroepiandosterone (DHEA) concentrations did not differ between survivors and non-survivors. Of the cytokines, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-8 concentrations were all significantly higher in non-survivors.

The ROC curves for multiple variables were derived; the area under the curve for each parameter is shown in Table 2. The variable with the largest ROC curve area was APACHE II score (0.75) followed by APS (0.70). Of the parameters that were a single variable (not a score), age was the most predictive (ROC area 0.67) followed by IL-8 (ROC area 0.65) and estradiol (ROC area 0.64) concentrations. Variables with no predictive value were white blood cell (WBC) count (ROC area 0.50) and BMI (ROC area 0.50). The predictive ability of estradiol was present in the trauma subset (ROC area 0.68), male patients (ROC area 0.67), and pre-menopausal female patients (ROC area 0.93). As estradiol concentration did not differ by outcome among the surgical subset and post-menopausal women, it was not a good predictor of outcome in these patient groups.

Table 2.

Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve for Variables in Predicting Death

| Variable | Area under curve |

|---|---|

| APACHE II score | 0.75 |

| APS | 0.70 |

| Patient age | 0.67 |

| MODS score | 0.65 |

| IL-8 | 0.65 |

| Estradiol | 0.64 |

| IL-6 | 0.61 |

| IL-10 | 0.60 |

| TRISS | 0.60 |

| IL-4 | 0.60 |

| ISS | 0.58 |

| Progesterone | 0.58 |

| TNF-α | 0.56 |

| IL-12 | 0.55 |

| IL-5 | 0.53 |

| IL-1 | 0.52 |

| Testosterone | 0.52 |

| White blood cell count | 0.50 |

| Body mass index | 0.50 |

| IL-2 | 0.50 |

| Prolactin | 0.50 |

| APACHE II + estradiol + age | 0.79 |

| APACHE II + age | 0.78 |

| APACHE II + estradiol | 0.77 |

| Age + estradiol | 0.74 |

APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; APS = Acute Physiology Score; MODS = Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome; IL = interleukin; TRISS = Trauma and Injury Severity Score; ISS = Injury Severity Score; TNF = tumor necrosis factor.

Figure 1 shows the ROC curve for estradiol compared with that of APACHE II score. The sensitivity, specificity, percent classified correctly, and likelihood ratio of different cut-points of serum estradiol are shown in Table 3. A cut-point of 50 pg/mL was 48% sensitive and 80% specific for predicting all-cause, 28-day mortality. A specificity of 100% could be achieved with a cut-point of 100 pg/mL, but with only 6% sensitivity. The percent of values correctly classified was best (88%) at values of 125 pg/mL and higher.

FIG. 1.

Receiver-operating characteristic curves for estradiol, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, and age in 417 critically ill and injured patients in predicting in-hospital, all-cause 28-day mortality rate. Area under the curve for estradiol is 0.64 (95% confidence interval 0.55, 0.72).

Table 3.

Test Characteristics of Different Cut-Points for Serum Estradiol

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Classified correctly (%) | Likelihood ratio positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undetectable (<10) | 100 | 0 | 13 | 1.0 |

| 25 | 54 | 60 | 59 | 1.3 |

| 50 | 48 | 80 | 76 | 2.3 |

| 75 | 30 | 90 | 83 | 3.2 |

| 100 | 21 | 95 | 86 | 4.2 |

| 125 | 20 | 98 | 88 | 7.7 |

| 150 | 15 | 98 | 88 | 9.2 |

| 175 | 12 | 99 | 88 | 13.8 |

| 200 | 6 | 100 | 88 | 20.8 |

DISCUSSION

The role of patient sex in determining outcomes of critical illness has been debated extensively. In this cohort, we did not detect a difference in outcomes between the sexes, although it must be remembered that the study sample was small. The sex hormone profile of this cohort is consistent with the endocrine response to critical illness [28], with elevation of estrogens and depression of testosterone in both men and women. Other investigators have demonstrated this estrogen increase to result from peripheral aromatization rather than decreased metabolism or clearance [28]. Non-survivors had significantly higher concentrations of estradiol than did non-survivors regardless of sex. Higher estrogen concentrations recently have been linked to death in medical ICU patients [8]. We sought to describe the test characteristics of serum estradiol at 48 h to predict the all-cause, 28-day, mortality rate in critically ill and injured surgical patients.

Death in the ICU is a complex and multifactorial event, and its prediction on the basis of a single variable can be difficult. The best success at prediction has come from physiologic or injury scores that combine a number of demographic, clinical, and physiologic variables into a single score. Not surprisingly, APACHE II was the best predictor of death in our population, with the highest ROC curve area (0.75). An APACHE II score of 23 was 50% sensitive and 81% specific for prediction of death. Similarly, APS—a component of APACHE II—was somewhat predictive of death (ROC area 0.70). For trauma patients, neither TRISS (ROC curve area 0.60) nor ISS (ROC curve area 0.58) was a powerful predictor. Indeed, neither score differed statistically between survivors and non-survivors, although TRISS scores trended toward statistical significance. These findings likely are attributable to the inherent limitations of these scoring systems [29].

Of the other parameters with a single variable, age was the best predictor of death (ROC curve area 0.67). Age is considered a strong determinant of outcomes and a particularly important confounder, given its association with multiple comorbid conditions. The BMI was not different in the two groups, and therefore had no predictive utility. Whereas some reports have suggested differential outcomes for obese patients, more recent studies have suggested that BMI is not a determinant of outcome if tight glycemic control is achieved.

Of the sex hormones, estradiol was the best predictor of death. With an ROC curve area of 0.64, its performance was better than BMI and similar to age. Serum estradiol values above 50 pg/mL had higher likelihood ratios, and were therefore associated with higher positive predictive values. The other sex hormones were not different between survivors and non-survivors, and thus did not predict death accurately. Of all the serum factors assayed, only IL-8 was a better predictor of death than estradiol (ROC curve area 0.65). Estradiol was a more accurate predictor than WBC count (ROC curve area 0.50). Whether estradiol is only a marker of the global inflammatory response or indeed plays some causal role in adverse outcomes, its use in the clinical setting may prove more helpful and specific than the commonly used WBC count. Further studies will be needed to determine the ability of estradiol to predict infection and other secondary outcomes.

One limitation of this study is that patients who died or were discharged prior to 48 h were excluded, restricting the ability to generalize these results. Particularly in the surgical and trauma populations, deaths occurring prior to 48 h often are the result of exsanguination, traumatic brain injury, or similar events that are unlikely to be affected by an inflammatory response. Similarly, patients discharged from the ICU prior to 48 h have a low mortality rate. It is unknown precisely how quickly estrogen concentrations increase, whether hospital admission panels would reveal similar elevations, or if a correlation with other outcome measures could be demonstrated in patients with less severe illness.

Another limitation is that this analysis is based on a single estradiol measurement at 48 h after ICU admission. Animal studies that demonstrate the protective effects of estrogens are based on measurements made close to the time of the injury or insult. It is impossible to know from these data whether the higher mortality rate associated with elevated estrogen concentrations is a function of a difference in timing of measurement. Measuring estrogen (and other cytokine and hormone concentrations) at the time of injury or other insult would introduce a number of complexities into the study design. In addition to the difficulties of obtaining consent and ensuring human subject protections for samples drawn in the pre-hospital setting, a larger sample size would likely be needed to demonstrate a difference in survival because the mortality rate of the population overall is considerably lower than the mortality rate of patients remaining in the ICU for at least 48 h. Despite these difficulties, studies of the relation of initial estrogen concentrations to death are needed.

Whereas the mixed nature of this population (both trauma and surgical patients) improves the ability to generalize the data, it limits the application of the conclusions to specific subgroups. Two-thirds of the study patients herein were trauma patients. This proportion did not differ between survivors and non-survivors; the difference in estradiol concentration by outcome was observed in this subset. More extensive and detailed subgroup analyses are a future goal (e.g., trauma vs. non-trauma, normal weight vs. obese, young vs. old), many more patients must be assessed to ensure adequate statistical power.

CONCLUSION

Estradiol as a predictor of death is a novel concept in critically ill and injured patients. We conclude that although it is inferior to scores that include multiple variables (e.g., APACHE II, APS) serum estradiol concentration at 48 h is useful as a single-variable predictor of death. Estradiol concentrations above 50 pg/mL are 48% sensitive and 80% specific for predicting death, and this or a similar cut-point should be considered as an informative prognostic tool in this patient population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant, R01 AI49989-01 (Clinical Trials.gov identifier NCT00170560).

Footnotes

Presented at the twenty-seventh annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society, Toronto, Canada, April 18-20, 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zellweger R, Wichmann MW, Ayala A, et al. Females in proestrus state maintain splenic immune functions and tolerate sepsis better than males. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:106–110. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199701000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samy TS, Knoferl MW, Zheng R, et al. Divergent immune responses in male and female mice after trauma-hemorrhage: Dimorphic alterations in T lymphocyte steroidogenic enzyme activities. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3519–3529. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.8.8322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizushima Y, Wang P, Jarrar D, et al. Estradiol administration after trauma–hemorrhage improves cardiovascular and hepatocellular functions in male animals. Ann Surg. 2000;232:673–679. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200011000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knoferl MW, Jarrar D, Angele MK, et al. 17 Beta-estradiol normalizes immune responses in ovariectomized females after trauma–hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:C1131–C1138. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.4.C1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knoferl MW, Angele MK, Diodato MD, et al. Female sex hormones regulate macrophage function after trauma—hemorrhage and prevent increased death rate from subsequent sepsis. Ann Surg. 2002;235:105–112. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200201000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majetschak M, Christensen B, Obertacke U, Waydhas C, Schindler AE, Nast-Kolb D, et al. Sex differences in posttraumatic cytokine release of endotoxin-stimulated whole blood: relationship to the development of severe sepsis. J Trauma. 2000;48:832–839. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wichmann MW, Inthorn D, Andress HJ, Schildberg FW. Incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in surgical intensive care patients: The influence of patient gender on disease process and outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:167–172. doi: 10.1007/s001340050041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angstwurm MW, Gaertner R, Schopohl J. Outcome in elderly patients with severe infection is influenced by sex hormones but not gender. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2786–2793. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000190242.24410.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romo H, Amaral AC, Vincent JL. Effect of patient sex on intensive care unit survival. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:61–65. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gannon CJ, Pasquale M, Tracy JK, et al. Male gender is associated with increased risk for postinjury pneumonia. Shock. 2004;21:410–414. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George RL, McGwin G, Jr, Metzger J, et al. The association between gender and mortality among trauma patients as modified by age. J Trauma. 2003;54:464–471. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000051939.95039.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valentin A, Jordan B, Lang T, et al. Gender-related differences in intensive care: A multiple-center cohort study of therapeutic interventions and outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1901–1907. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000069347.78151.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowles BJ, Roth B, Demetriades D. Sexual dimorphism in trauma? A retrospective evaluation of outcome. Injury. 2003;34:27–31. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(02)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Croce MA, Fabian TC, Malhotra AK, et al. Does gender difference influence outcome? J Trauma. 2002;53:889–894. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200211000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Napolitano LM, Greco ME, Rodriguez A, et al. Gender differences in adverse outcomes after blunt trauma. J Trauma. 2001;50:274–280. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200102000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oberholzer A, Keel M, Zellweger R, et al. Incidence of septic complications and multiple organ failure in severely injured patients is sex specific. J Trauma. 2000;48:932–937. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200005000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eachempati SR, Hydo L, Barie PS. Gender-based differences in outcome in patients with sepsis. Arch Surg. 1999;134:1342–1347. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.12.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crabtree TD, Pelletier SJ, Gleason TG, et al. Gender-dependent differences in outcome after the treatment of infection in hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1999;282:2143–2148. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.22.2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Offner PJ, Moore EE, Biffl WL. Male gender is a risk factor for major infections after surgery. Arch Surg. 1999;134:935–938. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.9.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroder J, Kahlke V, Staubach KH, et al. Gender differences in human sepsis. Arch Surg. 1998;133:1200–1205. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.11.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klaiber EL, Broverman DM, Haffajee CI, et al. Serum estrogen levels in men with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 1982;73:872–881. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90779-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fourrier F, Jallot A, Leclerc L, et al. Sex steroid hormones in circulatory shock, sepsis syndrome, and septic shock. Circ Shock. 1994;43:171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christeff N, Auclair MC, Dehennin L, et al. Effect of the aromatase inhibitor, 4-hydroxyandrostenedione, on the endotoxin-induced changes in steroid hormones in male rats. Life Sci. 1992;50:1459–1468. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90265-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheingraber S, Dobbert D, Schmiedel P, et al. Gender-specific differences in sex hormones and cytokines in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. Surg Today. 2005;35:846–854. doi: 10.1007/s00595-005-3044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simpson ER. Aromatase: Biologic relevance of tissue-specific expression. Semin Reprod Med. 2004;22:11–23. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-823023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson ER, Cleland WH, Mendelson CR. Aromatization of androgens by human adipose tissue in vitro. J Steroid Biochem. 1983;19(Suppl 1B):707–713. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(83)90239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simpson ER, Merrill JC, Hollub AJ, et al. Regulation of estrogen biosynthesis by human adipose cells. Endocr Rev. 1989;10:136–148. doi: 10.1210/edrv-10-2-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spratt DI, Morton JR, Kramer RS, et al. Increases in serum estrogen levels during major illness are caused by increased peripheral aromatization. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E631–E638. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00467.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chawda MN, Hildebrand F, Pape HC, Giannoudis PV. Predicting outcome after multiple trauma: Which scoring system? Injury. 2004;35:347–358. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]