Abstract

Objective

To examine the influence of kinship care on behavioral problems after 18 and 36 months in out-of-home care. Growth in placement of children with kin has occurred despite conflicting evidence regarding its benefits compared to foster care.

Design

Prospective cohort study

Setting

National Survey of Child & Adolescent Well-Being, October, 1999-March, 2004

Participants

1,309 children entering out-of-home care following a maltreatment report

Main Exposure

Kinship vs. general foster care

Main Outcome Measures

Predicted probabilities of behavioral problems derived from Child Behavior Checklist scores

Results

Fifty percent of children started in kinship care, and 17% of children who started in foster care later moved to kinship care. Children in kinship care were lower risk at baseline and less likely to have unstable placements than children in foster care. Controlling for a child's baseline risk, placement stability, and attempted reunification to birth family, the estimate of behavioral problems at 36 months was 32% (95% CI 25%−38%) if children in the cohort were assigned to early kinship care and 46% (95% CI 41%−52%) if children were assigned to foster care only (p=0.003). Children who moved to kinship care after significant time in foster care were more likely to have behavioral problems than children in kinship care from the outset.

Conclusions

Children placed into kinship care had fewer behavioral problems three years after placement than children who were placed into foster care. This finding supports efforts to maximize placement of children with willing and available kin when they enter out-of-home care.

Background

The last two decades have brought significant growth in the number of children being raised by relatives in kinship care across the United States. According to the 2005 census more than 2.5 million children were living with a relative caregiver other than a birth parent, representing a 55% increase from census reports in 1990.1 Although there are many circumstances in which a child may come to reside with kin, substantiated reports of child abuse or neglect might be the most common reason. In 2002, an estimated 542,000 children were living with kin following the involvement of a child welfare agency, exceeding the number of children living in non-relative foster care arrangements.2 The growth in kinship care is the result of a sustained effort to improve permanency for children since the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (P.L. 105−89). Since then, child welfare agencies have increased efforts to place children with kin despite scant and conflicting evidence of improved outcomes for children in kinship care compared to children in general foster care.

A review of the literature delineates conflicting evidence regarding the benefits and tradeoffs of raising children with kin. A large body of research acknowledges the evidence that children in kinship care are less likely to change placements, benefiting from increased placement stability compared to children in general foster care.3-6 Placement stability is a common goal of child welfare systems, and has consistently been shown to result in better outcomes for all children living in out-of-home care.7-9 Children in kinship care are also more likely to remain in their same neighborhood, be placed with siblings, and have consistent contact with their birth parents than children in foster care, all of which might contribute to less disruptive transitions into out-of-home care.7, 10-14

Other evidence raises concerns of safety for children in kinship arrangements given the greater risk of continued and often unsupervised access to abusive parents and a greater likelihood that the child's new relative caregivers share similar problems as offending parents.14, 15 Children in kinship care also have higher rates of behavioral and educational problems than other children living in poverty who are not involved with the child welfare system.10, 16, 17 Long-term outcome studies have also failed to demonstrate a significant difference between children raised by kin and foster parents.17-19 And finally, children in kinship care are known to face additional hardships because their caregivers tend to be single, older, of poorer health, of lower economic status, have more mental health problems, receive less assistance and services from child welfare agencies, and have fewer supportive resources than foster parents.2, 17, 20-23

Given this conflicting evidence, there is a need to better understand the experiences and outcomes of children in kinship care compared to general foster care. The recent National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW), mandated by Congress in 1996 and conducted for the Department of Health and Human Services, has provided a unique opportunity to capture the experiences and early outcomes of a nationally representative cohort of children placed in out-of-home care.24 We therefore sought to estimate the association between placement into kinship care and the likelihood of behavioral problems after 18 and 36 months in out-of-home care.

Methods

NSCAW was a complex survey that sought to recruit a nationally representative sample of American children following substantiated maltreatment reports to child protective services from October 1999 to December 2000. Interviews were conducted with children, caregivers, birth parents, child welfare workers, and teachers at baseline, 18 months, and 36 months after enrollment, with the completion of the 36-month follow-up occurring by March, 2004. Of the original 5,501 children enrolled in NSCAW, we restricted our sample to those children residing at home at the time of the initial investigation for maltreatment and who entered out-of-home care between the date of investigation and baseline data collection. We excluded subjects who spent more than nine of the first eighteen months in restrictive settings like group homes or residential treatment facilities because we were principally interested in the movement of children across the less restrictive settings of kinship and foster care.25 The response rate at baseline for the NSCAW sample was 61% (5501/8961, weighted 64%). However, our target population of children in out-of-home care was easier to recruit and therefore had a response rate approaching 88%.26

The main exposures of interest were the placement setting, placement stability, and reunification status of the children. For placement setting, we divided children into three categories: 1) early kinship care, if they had a placement in a kin home within one month of entry into out-of-home care; 2) if their placement with kin occurred beyond the first month of out-of-home care; and 3) general foster care, if they had no subsequent placements into kinship care. For placement stability over the first 18 and 36 months in out-of-home care, we followed previous work27, 28 and divided children into three distinct categories of stability: 1) early stable, in which a sustained placement or reunification was achieved within 45 days of entry into out-of-home care and lasted through the end of the study period (18 or 36 months); 2) late stable, in which a sustained placement or reunification was achieved after 45 days with a duration of at least half the study period; and 3) unstable, in which no long-lasting placement or reunification was achieved during the study period. A separate reunification variable was created to identify those children for whom a reunification to the birth family was attempted.

The primary outcome for this study was the child's behavioral well-being at 18 and 36 months, as measured by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).29 Scores for each item from this caregiver-reported survey are summed into a total behavioral problems scale, which is normalized by age to identify categories of normal, borderline (>83rd percentile), and clinical (>90th percentile) range behaviors. For the purposes of our study, we dichotomized the outcome variable at the 83rd percentile to denote normal versus abnormal behavior scores, a practice which has been used commonly in prior studies with this instrument. 20, 30-36

To encode a child's baseline risk, the major source of confounding in this study, we built upon prior work using ordinal regression models to estimate the future risk of placement stability using baseline attributes of the children and their families.28 Child-level factors for these models included gender, age (< 2 years, 2−10 years, > 10 years), race (white, black, or other), history of chronic health problems (yes/no), caregiver reported mental health service use (yes/no), use of prescription medications (yes/no), and the child's behavioral well-being at baseline. The behavioral well-being variable was a composite variable using standardized CBCL scores for children 2 years and older and standardized temperament scores for younger children that were used in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY). 28,37 Birth parent characteristics included histories of drug or alcohol abuse (yes/no), mental health problems (yes/no), and domestic violence or arrests (yes/no). Child maltreatment variables included the type of maltreatment (physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect/abandonment, other) and prior reporting/foster care history (yes/no).

Post-estimation probabilities of placement stability from the ordinal logistic regression models were reduced into three tertiles to represent low, medium or high risk groups. These tertiles were then added to logistic regression models for the outcome of any behavioral problem at 18 and 36 months. The other variables in these analyses were the child's placement setting, placement stability, and reunification status over the interval (either 18 or 36 months).

For the 18-month model, 392 children were under 2 years of age and just missed the cutoff for the CBCL. We used multiple imputation, with five imputed values per missing observation, to estimate the missing 18-month CBCL data38 using 36-month CBCL scores, the caregiver's report of mental health service use by children between baseline and 18 months, and all other independent variables that were ultimately included in the final models. A similar approach permitted the imputation of CBCL scores for 159 children at 36 months whose CBCL scores were unmeasured.39

After fitting the final models, we estimated predictive margins for the probability of behavior problems had all children been assigned to kinship or general foster care.40 These post-estimation methods allow for standardized comparisons of outcomes across different classifications of children. Estimates report the probability of behavioral problems if all children in the sample shared the same experience while averaging over other covariates in the model. Reporting adjusted probabilities of behavioral outcomes was preferred to reporting risk ratios because the prevalence of behavioral problems was high in the population.

All variances estimates accounted for the stratification, clustering, and sampling weights in NSCAW. The extreme variability in weights (range: 1 − 6908) led us to mirror prior analyses and trim the design weights above the 95th percentile.28, 41 Separate analyses revealed that trimming weights in this manner reduced the variance of estimates without significantly affecting point estimates. In addition, variances estimates reflect the variability of using imputed data. Variances for the predictive margins within imputed dataset were estimated using bootstrap resampling at the primary sampling unit level (999 samples). Within and among-imputation components of variance were then combined to form the final confidence intervals for these marginally standardized probabilities.42 Sensitivity analyses (not shown) comparing multiple imputation versus excluding the younger children did not appreciably change our results, nor did constructing a model with adjustment for all covariates simultaneously or adding back into the model the covariates that were used initially to estimate the predicted probability of placement stability.

Analyses were conducted using Stata.43 Permission to use the NSCAW data was granted by the National Data Archive for Child Abuse and Neglect. Approval for the study was obtained from the institutional review board at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Results

Among the NSCAW cohort, 1,404 children entered out-of-home care between their maltreatment report and the subsequent baseline data collection. Of these children, 1,309 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria of our study (93% of potential eligibles). At baseline, 28% of the children were < 2 years, 50% were 2 to 10 years, and 22% were > 10 years old. Most children (57%) were reported because of neglect or abandonment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of children entering out-of-home care within the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-being (NSCAW).*

| Initial placement setting |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Foster care (50.3%; n = 710) | Kinship care (49.7%; n = 599) | p-value |

|

DEMOGRAPHICS | |||

| Child's age | |||

| <2 years | 29.8 (304) | 26.0 (230) | |

| 2−10 years | 45.7 (260) | 54.6 (269) | 0.12 |

| >10 years | 24.5 (145) | 19.4 (100) | |

|

Child's gender | |||

| Female | 52.0 (354) | 55.9 (333) | 0.42 |

| Male | 48.0 (356) | 44.2 (266) | |

|

Child's race | |||

| White | 52.1 (318) | 47.9 (259) | |

| Black | 35.0 (285) | 41.2 (268) | 0.37 |

| Other |

12.8 (107) |

10.9 (72) |

|

|

Hispanic ethnicity |

13.7 (103) |

12.9 (108) |

0.76 |

| Below poverty level** | 23.0 (129) | 44.0 (228) | <0.001 |

|

CHILD BASELINE HEALTH | |||

|

Abnormal behavior† |

42.1 (249) |

32.8 (179) |

0.04 |

|

Health problems |

46.5 (354) |

42.1 (262) |

0.34 |

|

Prescription medication use |

3.2 (19) |

0.6 (7) |

0.005 |

| Mental health service use | 35.4 (228) | 24.3 (137) | 0.003 |

|

MALTREATMENT HISTORY | |||

| Type of abuse reported | |||

| Neglect/abandonment | 56.0 (392) | 58.6 (314) | 0.90 |

| Physical abuse | 18.6 (112) | 18.6 (106) | |

| Sexual abuse | 9.5 (73) | 8.8 (50) | |

| Other |

15.8 (72) |

13.9 (76) |

|

| Prior child protective services involvement | 69.2 (478) | 61.9 (358) | 0.06 |

|

BIRTH PARENT CHARACTERISTICS | |||

|

Mental health problems |

58.4 (414) |

46.6 (290) |

0.006 |

|

Domestic violence or incarceration |

50.7 (354) |

52.6 (306) |

0.59 |

| Substance abuse | 45.3 (365) | 47.9 (311) | 0.54 |

|

BEHAVIORAL OUTCOMES | |||

|

Abnormal 18-month CBCL scores†† |

47.1 (214) |

31.4 (169) |

0.001 |

| Abnormal 36-month CBCL scores†† | 48.0 (250) | 29.1 (173) | <0.001 |

Percentages are based on survey-weights (n= sample numbers, unweighted)

For child's initial placement setting in out-of-home care; Poverty level defined as household income less than $20,000/year for family of five (median household size in NSCAW out-of-home sample = 5); Weighted average poverty threshold for household of five in 1999 = $20,127 (U.S. Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/threshld/thresh99.html).

Defined as > 1 S.D. from mean using standardized infant temperament score if child <2 years of age; Child Behavior Checklist score if ≥ 2 years

Numbers and percentages presented in table based on non-imputed data. Estimates based on imputed data are as follows: abnormal 18-month CBCL scores – foster care (44.7%), kinship care (29.8%); abnormal 36-month CBCL scores – foster care (46.4%), kinship care (29.0%).

Our sample was evenly divided between children who entered kinship care at their initial placement (50%) and those who entered general foster care (50%). Among children who initially entered general foster care, 17% later moved to kinship care (late kinship care) after having spent at least one month in foster care. Thirty-five percent of children had an attempted reunification with birth families, with a greater proportion of attempts made for children in general foster care than kinship care (43% vs. 28%). Children initially placed into general foster care were also more likely to have had an abnormal baseline behavior score, to have taken medications in the 12 months prior to the start of the study, to have used mental health services at the time of baseline data collection, and to have had a caregiver with serious mental health problems as compared to children who initially entered kinship care (Table 1).

After further delineating the onset of kinship care as early or late, children in early kinship care were more likely to be at lower risk for placement instability than both children in late kinship care and general foster care only (Table 2). Children in early kinship care were also more likely to achieve early stability; by 36 months, 58% of children in early kinship care were classified as early stable, compared to only 32% of children in general foster care. Although by definition unable to achieve early stability, 58% of late kinship care children still achieved later stability compared to 40% of children in general foster care only.

Table 2.

Baseline risk for placement instability and observed placement stability over the first 36 months of out-of-home placement, by placement setting.*

| Placement setting |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | General foster care only (n=584) | Late kinship care (n=126) | Early kinship care (n=599) | p-value |

| Risk for instability† | ||||

| Low | 31.5 (155) | 34.0 (39) | 45.7 (240) | |

| Medium | 32.7 (230) | 34.9 (51) | 31.8 (210) | 0.01 |

| High | 35.8 (190) | 31.1 (36) | 22.6 (147) | |

|

Actual placement stability | ||||

| Early stable | 32.1 (171) | 3.9 (4) | 57.5 (299) | |

| Late stable | 39.5 (236) | 57.7 (76) | 24.9 (174) | <0.001 |

| Unstable | 28.4 (137) | 38.4 (46) | 17.6 (126) | |

Percentages are based on survey-weights. (n=sample size, unweighted).

Risk groups derived from multivariable ordinal logistic regression model predicting log odds of placement instability using baseline attributes; Variables included in model - baseline behavior score (temperament score if <2 years of age, Child Behavior Checklist if ≥ 2 years), child's age, reported mental health service use, prescription medication use within one year prior to entry into NSCAW, history of prior child protective services involvement, and birth parent with mental/behavioral health problems.

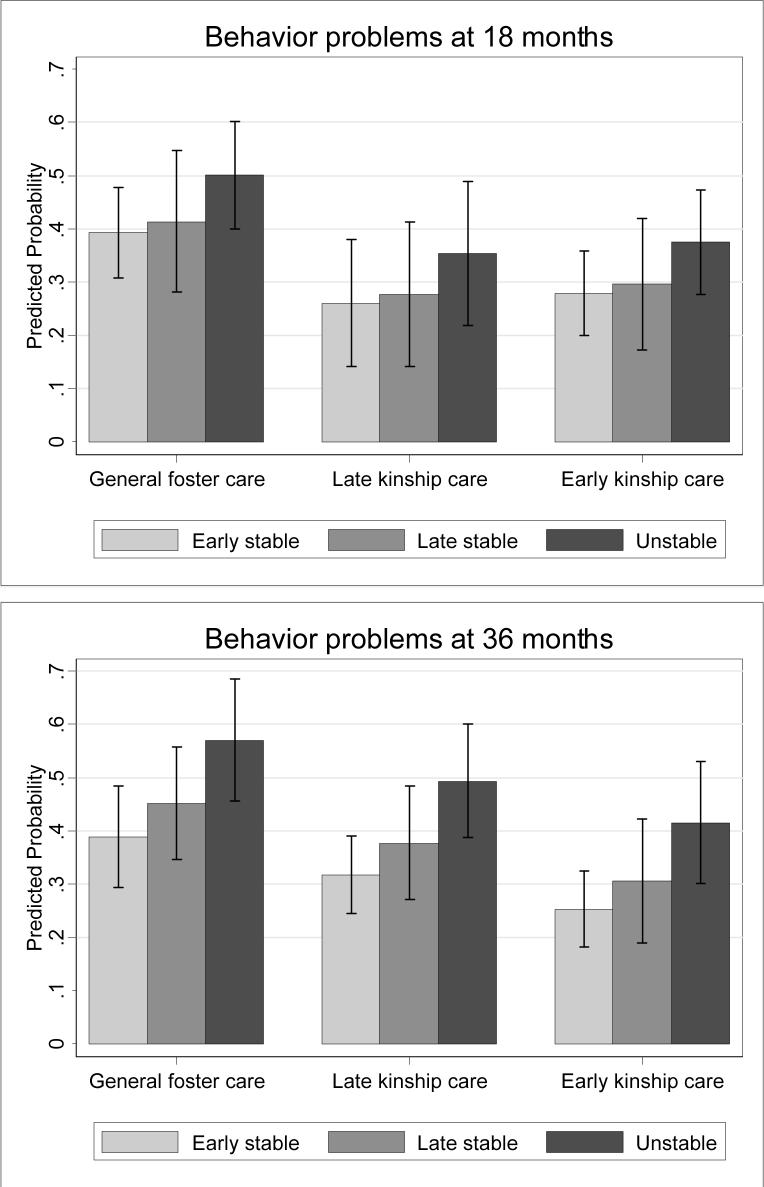

Controlling for placement stability, baseline risk, and reunification status at 18 and 36 months, children in early kinship care had a lower marginal probability of behavioral problems by 36 months (Table 3). The estimate of behavioral problems was 46% (95% CI 41%−52%) if all children had been assigned to general foster care only, compared to 32% (95% CI 25%−38%) if the children had been assigned to early kinship care.. If kinship care had occurred late, by contrast, the estimated risk of behavioral problems was 39% (95% CI 34%−43%). With regards to placement stability, the probability of behavioral problems was 49% (95% CI 39%−60%) if children had an unstable placement history, compared to 32% (95% CI 25%−39%) if children were conferred early stability. Finally, in a two-dimensional analysis across all categories of placement stability, there was a lower expected probability of behavior problems if children had entered early kinship care versus general foster care (Figure 1); the risk of behavioral problems if children had entered late kinship care fell between these two groups.

Table 3.

Adjusted probabilities of behavior problems at 18 and 36 months of children entering out-of-home care in the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-being.*

| Variable | 18 months | 36 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability | 95% C.I. | p-value | Probability | 95% C.I. | p-value | |

| Placement setting | ||||||

| General foster care only | 0.44 | (0.37 − 0.50) | Ref | 0.46 | (0.41 − 0.52) | Ref |

| Late kinship care | 0.30 | (0.19 − 0.41) | 0.13 | 0.39 | (0.34 − 0.43) | 0.003 |

| Early kinship care | 0.32 | (0.25 − 0.39) | 0.02 | 0.32 | (0.25 − 0.38) | 0.003 |

|

Actual placement stability | ||||||

| Early stable | 0.33 | (0.26 − 0.40) | Ref | 0.32 | (0.25 − 0.39) | Ref |

| Late stable | 0.35 | (0.23 − 0.46) | 0.95 | 0.38 | (0.27 − 0.48) | 0.52 |

| Unstable | 0.43 | (0.35 − 0.51) | 0.14 | 0.49 | (0.39 − 0.60) | 0.007 |

|

Risk for instability† | ||||||

| Low | 0.25 | (0.19 − 0.31) | Ref | 0.33 | (0.27 − 0.40) | Ref |

| Medium | 0.37 | (0.32 − 0.42) | <0.001 | 0.39 | (0.35 − 0.43) | 0.04 |

| High | 0.51 | (0.43 − 0.60) | <0.001 | 0.45 | (0.38 − 0.52) | 0.04 |

|

Reunification status | ||||||

| No | 0.31 | (0.25 − 0.37) | Ref | 0.37 | (0.28 − 0.45) | Ref |

| Yes | 0.56 | (0.36 − 0.76) | 0.11 | 0.43 | (0.25 − 0.62) | 0.62 |

Standardized estimates of predictive margins, derived from survey-weighted logistic regression. Each probability derived under the assumption that all children in cohort assigned to that category, adjusting for all other factors in the model.

Risk groups derived from multivariable ordinal logistic regression model predicting likelihood of placement instability using baseline attributes; Variables included in model - baseline behavior score (temperament score if <2 years of age, Child Behavior Checklist if ≥ 2 years), child's age, reported mental health service use, prescription medication use within one year prior to entry into NSCAW, history of prior child protective services involvement, and birth parent with mental health problems.

Figure 1. Standardized estimates of behavior problems at 18 and 36 months stratified by a child's placement setting and placement stability.*.

* Marginally standardized using survey-weighted logistic regression, adjusting for the risk for 520 instability and reunification status of the child. Probabilities presented with 95% confidence 521 intervals.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated a protective effect of kinship care on the early behavioral outcomes of a nationally representative cohort of children entering out-of-home care. Compared to children entering foster care, children entering kinship care had a lower estimated risk of behavioral problems, even after accounting for their lower baseline risk and increased placement stability. Even children who moved to kinship care after sustained periods of foster care showed some benefit. The magnitude of this association between placement setting and later behavioral problems should reassure a child welfare community that has increasingly moved children toward kinship placements in recent years.

While this study provides evidence to encourage the placement of children with willing and available kin, we urge caution in interpreting the findings for three reasons. First, NSCAW did not collect sufficient information about extended families to clarify whether children placed into foster care had acceptable and safe alternatives within their own families. While the late kinship care group demonstrated that at least some of these children had available kin, for others kinship care will likely remain an unrealistic option. For these children, our secondary finding that placement stability improves behavioral outcomes for all children affirms prior findings28 and provides an appealing option for intervention to improve outcomes over time, regardless of placement into kinship care or general foster care. Second, reporter bias might have contributed to some of our findings. Prior studies have demonstrated that kin caregivers might be less likely to report behavioral problems among children in their care than foster parents or teachers.44, 45 Our analyses did, however, adjust for baseline behavioral assessments, and many of these assessments were provided by the same kin caregivers who later reported outcome data. Finally, the results are not the product of a randomized study and it remains possible that unobserved confounding might explain both the assignment of placement setting and differences in behavioral outcomes.

Beyond these limitations and the need for further research to confirm and elaborate upon these findings are further concerns about generlizability because these data, although broad, cannot incorporate local variations and may not reach the entire universe of children in kinship care. The decision to place a child in kinship care often involves appraising the trade-offs of granting prompt access to kin, delaying access to permit time for certification, or—increasingly in recent years--moving children away from the system to temporary legal custody arrangements. Many of these latter circumstances, in which an open case to child welfare is quickly closed after the child is placed with a kin caregiver, involve caregivers who would have a difficult time achieving certification as a foster parent within the child welfare system, whether due to specific income or health criteria or simply scheduling compliance with the training necessary for certification. For these families, temporary legal custody arrangements have become an expedient alternative that might also shield them from continued scrutiny. Unfortunately, children in these more informal kinship arrangements would not have been easily identified within the NSCAW cohort. As such, their outcomes were likely unmeasured in this analysis and will require further study.

These generalizability concerns aside, it is still hard to overlook the magnitude of the protective effect observed for children in kinship care. At the same time, family members who provide kinship care (often to several siblings) are not without needs themselves, given health problems and poverty stemming from intergenerational cycles of maltreatment. Although children in kinship care fared better than children in foster care in this study, overall rates of behavioral problems in both groups exceed rates observed in other children who are raised in-home without involvement of the child welfare system.24 Furthermore, even in comparison to a foster care population whose needs are systematically unaddressed,46-49 the literature suggests that the unmet needs for kinship families are even greater, given the barriers to accessing public programs that are magnified when families lack the support of the child welfare system. Although the longitudinal impact of poverty could not be measured accurately among children in out-of-home care with the NSCAW data, at baseline we estimated that 44% of children entering kinship care resided with families whose income was below the federal poverty level, as compared with 23% of their peers who entered foster care. In addition, an Urban Institute report in 2002 found that only one third of informal kinship families even obtained the cash assistance benefits from Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) for which their children were eligible.50 Access to education, Medicaid, mental health services, and other benefits also pose barriers difficult for kin to overcome.2, 30, 50

These concerns about the support provided to kinship families have risen to the federal level of policy. Legislation has been introduced in the 110th Congress that would provide funding for states to provide guardianship benefits to kinship caregivers and to develop navigator programs that would link these caregivers to appropriate services and funding streams for children under their care.51, 52 This legislation would also require notification to kin upon the placement of a relative child in protective custody to facilitate early placement with relatives, potentially increasing the number of children who will enter kinship care early. Our findings suggest that more timely entry into kinship care will be beneficial: when kinship care is a realistic option and appropriate safeguards have been met, children in kinship care might have an advantage over children in foster care in achieving permanency and improved well-being, albeit with the recognition that their needs will remain great, exceeding those of children who have not been victimized by child maltreatment.

Acknowledgements

Funding/Support: This study is supported by Dr. Rubin's Career Development Award from NICHD (5K23HD045748) and by a supplemental grant from the Office of Research, Planning and Evaluation for the Administration of Children and Families at the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS 90PH0003−01). Additional support was also provided by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (KJD).

Footnotes

Role of the Sponsor: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study, nor the collection, management, analysis, interpretation of data, nor the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

The authors have indicated no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have indicated no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau [April 6, 2007]; Living arrangements of children under 18 years old: 1960 to present - Table CH-1: http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hh-fam.html.

- 2.Ehrle J, Geen R, Main R. Kinship foster care: custody, hardships, and services. The Urban Institute; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chamberlain P, Price JM, Reid JB, Landsverk J, Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M. Who disrupts from placement in foster and kinship care? Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30(4):409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courtney M, Needell B. Outcomes of kinship care: lessons from California. In: Berrick J, Barth R, Gilbert N, editors. Child Welfare Research Review. Vol. 2. Columbia University Press; New York: 1997. pp. 130–150. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iglehart A. Kinship foster care: placement, service, and outcome issues. Child Youth Serv Rev. 1994;16(1−2):107–122. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leslie LK, Landsverk J, Horton MB, Ganger W, Newton RR. The heterogeneity of children and their experiences in kinship care. Child Welfare. 2000;79(3):315–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berrick J, Barth R, Needell B. A comparison of kinship foster homes and foster family homes: implications for kinship foster care as family preservation. Child Youth Serv Rev. 1994;16(1−2):33–63. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown S, Cohon D, Wheeler R. African American extended families and kinship care: how relevant is the foster care model for kinship care? Child Youth Serv Rev. 2002;24(1−2):53–77. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Testa M. Kinship care in Illinois. In: Berrick J, Barth R, Gilbert N, editors. Child Welfare Research Review. Vol. 2. Columbia University Press; New York: 1997. pp. 101–129. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beeman S, Boisen L. Child welfare professionals’ attitudes toward kinship foster care. Child Welfare. 1999;78(3):315–337. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman MV, Wall A, Barth RP. Children's voices: the perceptions of children in foster care. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74(3):293–304. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubowitz H, Feigleman S, Harrington D, Starr R, Zuravin S, Sawyer RJ. Children in kinship care: how do they fare? Child Youth Serv Rev. 1994;16(1−2):85–106. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Messing JT. From the child's perspective: a qualitative analysis of kinship care placements. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2006;28(12):1415–1434. [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States General Accounting Office Kinship care quality and permanency issues: Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on Human Resources, Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives. 1999.

- 15.Peters J. True ambivalence: child welfare workers’ thoughts, feelings, and beliefs about kinship foster care. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2005;27:595–614. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawyer RJ, Dubowitz H. School performance of children in kinship care. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18(7):587–597. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks D, Barth R. Characteristics and outcomes of drug-exposed and non drug-exposed children in kinship and non-relative foster care. Child Youth Serv Rev. 1998;20:475–501. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benedict MI, Zuravin S, Stallings RY. Adult functioning of children who lived in kin versus nonrelative family foster homes. Child Welfare. 1996;75(5):529–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iglehart A. Readiness for independence: comparison of foster care, kinship care, and nonfoster care adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev. 1995;17(3):417–432. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burns B, Phillips S, Wagner H, et al. Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: a national survey. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):960–970. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehrle J, Geen R. Kin and non-kin foster care - findings from a national survey. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2002;24(1):):15–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gebel T. Kinship care and nonrelative family foster care: a comparison of caregiver attributes and attitudes. Child Welfare. 1996;75(1):5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timmer SG, Sedlar G, Urquiza AJ. Challenging children in kin versus nonkin foster care: perceived costs and benefits to caregivers. Child Maltreat. 2004;9(3):251–262. doi: 10.1177/1077559504266998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dubowitz H, Zuravin S, Starr RH, Jr., Feigelman S, Harrington D. Behavior problems of children in kinship care. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1993 Dec;14(6):386–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkins RP, Almeida MC, Fabry B, Reitz AL. A scale to measure restrictiveness of living environments for troubled children and youths. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1992;43(1):54–58. doi: 10.1176/ps.43.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being . Combined Waves 1−4 User's Manual - Restricted Release. National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect; Ithaca, NY: Aug 31, 2004. pp. 114–116. [Google Scholar]

- 27.James S, Landsverk JA, Slymen DJ. Placement movement in out-of-home care: patterns and predictors. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2004;26(2):185–206. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin D, O'Reilly A, Luan X, Localio A. The Impact of Placement Stability on Behavioral Well-being for Children in Foster Care. Pediatrics. 2007;119:336–344. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Achenbach T, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leslie LK, Landsverk J, Ezzet-Lofstrom R, Tschann JM, Slymen DJ, Garland AF. Children in foster care: factors influencing outpatient mental health service use. Child Abuse Negl. 2000 Apr;24(4):465–476. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurlburt M, Leslie L, Landsverk J, et al. Contextual predictors of mental health service use among children open to child welfare. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:1217–1224. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.12.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.James S, Landsverk J, Slymen DJ, Leslie LK. Predictors of outpatient mental health service use-the role of foster care placement change. Health Services Research. 2004;6(3):127–141. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000036487.39001.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James S, Landsverk JA, Slymen DJ. Placement movement in out-of-home care: patterns and predictors. Children & Youth Services Review. 2004;26(2):185–206. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landsverk J, Davis I, Ganger W, Newton R. Impact of child psychosocial functioning on reunification from out-of-home placement. Children & Youth Services Review. 1996;18(4−5):447–462. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landsverk J, Garland AF. Foster care and pathways to mental health services. In: Curtis PA, Dale GJ, editors. The foster care crisis: Translating research into policy and practice Child, youth, and family services. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, NE: 1999. pp. 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Landsverk JA, Garland AF, Leslie LK. Mental health services for children reported to child protective services. Vol. 2. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mott F, Baker P, Ball D, Keck C. The NLSY Children 1992. Center for Human Resource Research, Ohio State University; Columbus, OH: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Buuren S, Boshuizen H, Knook D. Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Stat Med. 1999;18:681–694. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<681::aid-sim71>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata Journal. 2004;4(3):227–241. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Korn E, Graubard B. Analysis of large health surveys. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korn E, Graubard B. Analysis of large health surveys. Accounting for the sampling design. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 1995;58:263–295. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubin D. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 43.StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 9.2. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shore N, Sim K, Keller T. Foster Parent and Teacher Assessments of Youth In Kinship and Non-Kinship Foster Care Placements: Are Behaviors Perceived Differently Across Settings? Child Youth Serv Rev. 2002;24(1−2):109–134. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keller T, Wetherbee K, Le Prohn N, Payne V, Sim K, Lamont E. Competencies and problem behaviors of children in family foster care: variations by kinship placement status and race. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2001;23(12):915–940. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burns B, Phillips S, Wagner H, et al. Mental Health Need and Access to Mental Health Services by Youths Involved With Child Welfare: A National Survey. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2004 Aug;43(8):960–970. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simms MD, Halfon N. The health care needs of children in foster care: A research agenda. Child Welfare. 1994;73(5):505–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Early Childhood and Adoption and Dependent Care. Health care of young children in foster care. Pediatrics. 2002;109(3):536–541. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Halfon N, Mendonca A, Berkowitz G. Health status of children in foster care. The experience of the Center for the Vulnerable Child. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995 Apr;149(4):386–392. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170160040006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Main R, Macomber J, Geen R. Assessing the New Federalism - Policy Brief B-68. The Urban Institute; Washington, DC: 2006. Trends in Service Receipt: Children in Kinship Care Gaining Ground. [Google Scholar]

- 51.The Kinship Caregiver Support Act, S 661, 110th Congress, 1st Sess. 2007.

- 52.The Kinship Caregiver Support Act, HR 2188, 110th Congress, 1st Sess. 2007.