Abstract

The macromolecular crystallography experiment lends itself perfectly to high-throughput technologies. The initial steps including the expression, purification and crystallization of protein crystals, along with some of the later steps involving data processing and structure determination have all been automated to the point where some of the last remaining bottlenecks in the process have been crystal mounting, crystal screening and data collection. At the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL), a National User Facility which provides extremely brilliant X-ray photon beams for use in materials science, environmental science and structural biology research, the incorporation of advanced robotics has enabled crystals to be screened in a true high-throughput fashion, thus dramatically accelerating the final steps. Up to 288 frozen crystals can be mounted by the beamline robot (the Stanford Automated Mounter, or SAM) and screened for diffraction quality in a matter of hours without intervention. The best quality crystals can then be remounted for the collection of complete X-ray diffraction data sets. Furthermore, the entire screening and data collection experiment can be controlled from the experimenter’s home laboratory by means of advanced software tools that enable network-based control of the highly automated beamlines.

Keywords: protein crystallography, cryocrystallography, high-throughput screening, robotics, remote access

Introduction

The protein crystallography (PX) experiment comprises a number of distinct steps, beginning in the wet lab with protein expression and purification, and the growth of protein crystals. The crystallographic steps which follow include crystal freezing and mounting, screening of the crystals for diffraction quality, diffraction data collection and processing, and structure determination. The final stage involves the analysis of the structure, correlation with enzyme function and the derivation of bioinformatics information. Recent advances in robotics and computer control, driven to some extent by structural genomics initiatives around the world, has seen the almost complete automation of the first three steps to the extent where, in some laboratories, huge numbers of protein crystals are being produced.1 This, coupled with the development of software which has greatly decreased the length of time required to process diffraction data, and solve and refine a protein structure, has shifted the bottlenecks in the PX process to the central steps involving crystal mounting, crystal screening and data collection.

In an effort to produce a true high-throughput crystal screening and data collection facility, and improve the efficient use of the synchrotron radiation resource, the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) Structural Molecular Biology Group and the Structure Determination Core of the Joint Center for Structural Genomics (JCSG)1 have worked together to develop the Stanford Auto-Mounting (SAM) system.2 The SAM system, combining a 4-axis industrial robot and a liquid filled dispensing dewar, is integrated with user-friendly software to provide a fully automated and highly efficient method for mounting and dismounting pre-frozen protein crystals, and screening samples for x-ray diffraction quality. In 2004, the SAM system was made available to general experimenters during the first SPEAR3 run on three beamlines. It was used during 60 experimental runs by 30 different research groups. Over 3500 crystals were screened, significantly increasing the efficiency of their experiments, such that many research groups finished before their beam time allocation ended. During the same period, members of the JCSG group used SAM to screen more than 2000 crystals from 125 target proteins. From these, 56 datasets were collected from 36 unique proteins, resulting in 30 new structures.

Now all seven SSRL macromolecular crystallography beamlines, BL1-5, BL7-1, BL9-1, BL9-2, BL11-1, BL11-3 and BL12-2 (currently in commissioning), have the SAM system installed and seamlessly integrated into the Blu-Ice/DCS beamline control system and graphical user interface developed at SSRL.3 This rapid, highly efficient and reliable robotic system gives the experimenters the opportunity to screen up to 288 crystals in a matter of hours without intervention. A typical screening sequence takes 3.5 minutes per crystal (robotic crystal mounting, automatic sample loop centering in the x-ray beam, video and diffraction image acquisition at 0 and 90°, and dismounting). Data collected during sample screening are automatically analyzed. The results include the number of spots, Bravais lattice, unit cell, estimated mosaicity, and resolution.

The SAM system has provided an increase in the quality of the diffraction data. Manual screening is typically one of the most tedious steps of a crystal structure determination, requiring repeated entry into the experimental hutch carrying small liquid nitrogen dewars and mounting the crystals onto the beamline goniometer using cryo-tongs. The quality of the crystal selected for data collection often depends more on the patience of experimenter rather than on the number of samples available. Using SAM, experimenters are able to easily and reliably screen all of their crystals before selecting the best quality crystal for data collection.

System Description

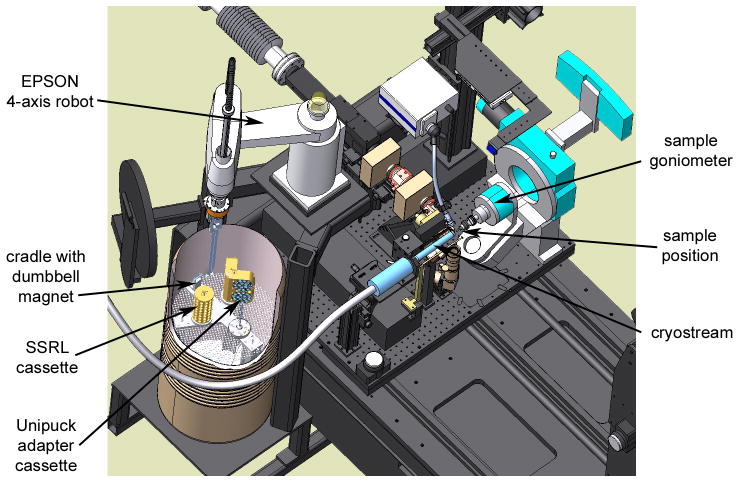

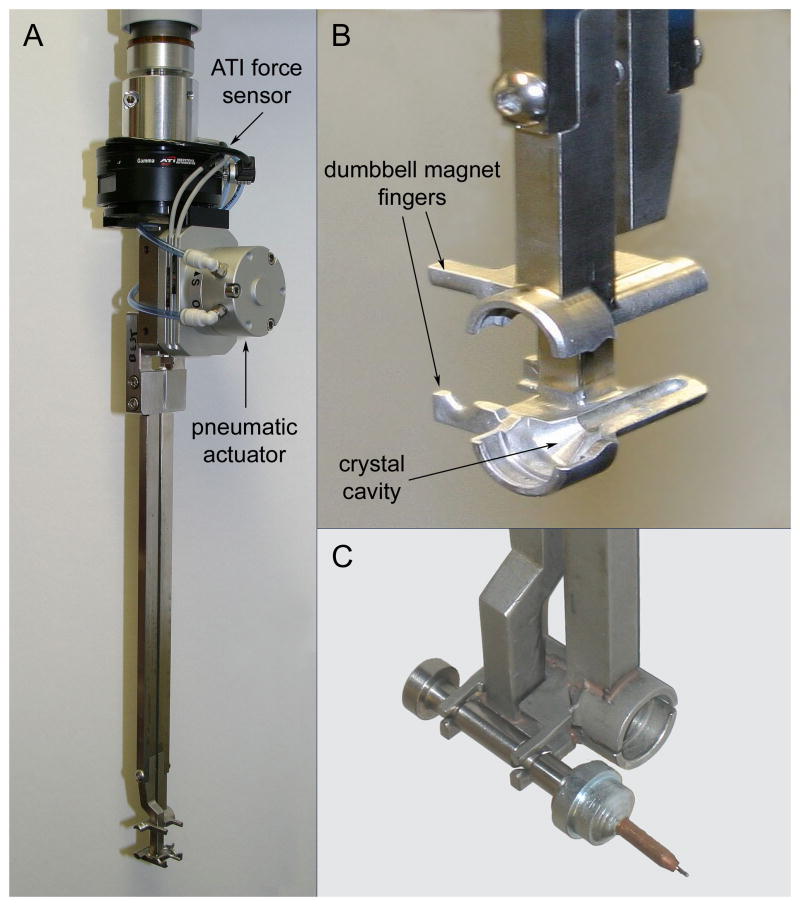

The SAM system (Figure 1) is centered on an off-the-shelf Epson E2S553S four-axis robot. The Epson model was chosen because it is very durable, requiring minimal maintenance for reliable operation, and it is small enough to be conveniently accommodated at the beamline while still providing an adequate range of motion. The translation shaft of the robot is fitted with an air-activated multifunctional crystal transport tong developed at SSRL and an ATI force sensor (Figure 2A). One side of the transport tong has small fingers used to grip a dumbbell-shaped magnetic sample manipulation tool, and the opposite side has a cavity (Figure 2B) used to envelop the sample pin and maintain the crystal at cryogenic temperature as it is transferred to the goniometer. The other major component of the SAM system is a liquid nitrogen filled dispensing dewar (Figure 1) able to hold three SSRL sample storage cassettes or 12 uni-puck storage containers in three adaptor cassettes.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of part of an SSRL protein crystallography beamline showing the SAM system which includes the 4-axis Epson robot and a cutaway of the robot dewar holding the dumbbell magnet and the sample cassettes.

Figure 2.

The SAM system. A) The SSRL-designed air-activated multifunctional crystal transport tong. The tong is attached to the robot translation shaft (top) and fitted with an ATI force sensor (black) and a pneumatic actuator for opening and closing the tongs. B) Close up view of the tong showing the sample cavity on one side and the fingers for manipulating the dumbbell magnet on the other. C) The dumbbell magnet gripped in the transport tong.

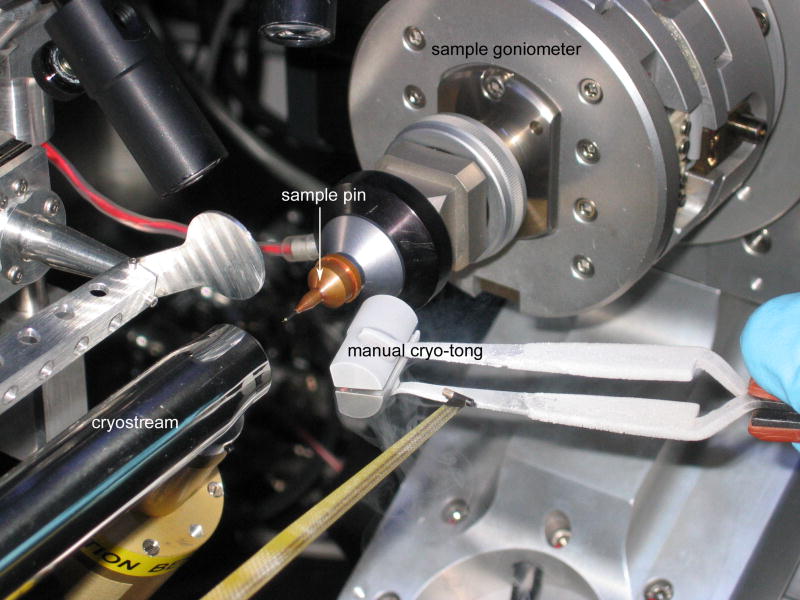

Traditionally, crystals have been mounted manually using cryo-tongs which are pre-cooled and then used to envelope the sample pin keeping it cold during transfers (Figure 3). This method has proved to be very reliable, albeit tedious when repeated many times. During the development of the transfer tong at SSRL, this was taken into account, such that the tong that is in use today on the seven SAM systems installed at SSRL, along with similar systems in place in several other synchrotron sources including the Photon Factory in Japan, the NSRRC in Taiwan, the Australian Synchrotron,4 and the Canadian Light Source is based upon the tried and true methods used by protein crystallographers since the 1990s.5 The sample pin carrying the crystal is enclosed inside the cavity and the total transfer time from the dispensing dewar to the beamline goniometer is approximately two seconds, comparable to a scientist manually mounting a crystal with cryo-tongs.

Figure 3.

Traditional manual sample mounting with an SSRL-style cryo-tong.

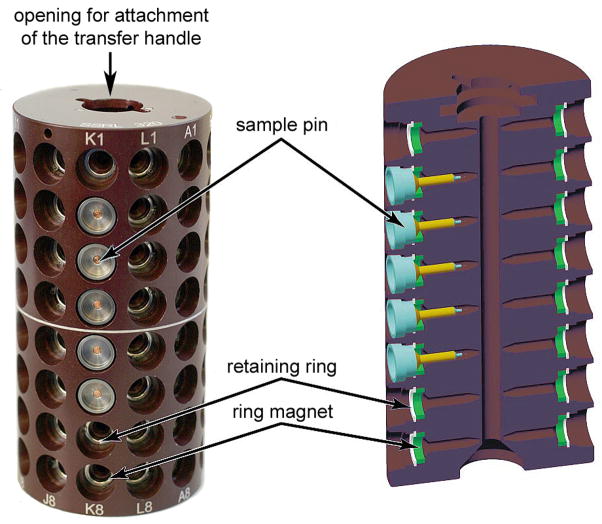

The SAM system is compatible with SSRL cassettes and uni-puck sample storage containers. The SSRL sample cassettes are 96-port hard-anodized aluminum cylinders (Figure 4), with each port able to accommodate one steel-based sample pin held in place by a ring magnet. Sample pins compatible with the cassette include the standard Hampton Research pins (CrystalCap Magnetic with 14, 18, and 21 mm long microtubes and 14, 16, and 18 mm CrystalCap Copper Magnetic pins with 10 mm microtubes), MiTeGen-style and ALS-style pins (developed at the Advanced Light Source) of similar length. A transfer handle, which fits into a machined opening in the top of the cassette, is used to facilitate the movement of a sample cassette from a dry-shipping transport dewar that the experimenter has sent to SSRL, into the dispensing dewar. The temperature at the crystal position within each port remains below 100 K for more than two minutes after the cassette is removed from liquid nitrogen and placed at room temperature. The uni-pucks are a recent development as part of a collaboration among developers at synchrotrons throughout the United States which allows experimenters to take advantage of automated sample mounting systems at many synchrotron facilities.4 Four uni-pucks are mounted in a uni-puck adapter cassette (Figure 1) such that the sample pins are positioned base out in a horizontal orientation, where they can be accessed by the SAM system in the same way it accesses sample pins in a SSRL cassette.

Figure 4.

The SSRL sample cassette (left) and a cutaway schematic view showing the positions of the ring magnets and the retaining ring. The location of the sample pins within the ports are also indicated. The machined opening on the top of the cassette for attachment of the transfer handle (not shown) is also indicated.

The magnetic dumbbell tool (Figure 2C) has different strength permanent magnets on each end, with the stronger end designed to extract the sample pin from the storage cassette, and the weaker end used to replace the samples. The tool is always submerged in the liquid nitrogen dewar, either resting on a cradle or held by the fingers on the side of the transfer tongs. After a sample pin has been removed from the cassette using the strong magnet, the dumbbell is placed on the cradle and the robot relocates the transfer tong to encapsulate the sample pin in the tong cavity, remove it from the dumbbell tool and transfer it to the beamline goniometer. During the sample replacement step, the pin is removed from the goniometer using the pre-cooled tong and placed onto the weak end of the magnet tool. The fingers then pick up the magnet tool and the pin is replaced into the empty port in the sample storage cassette. After each new sample has been mounted, the crystal transport tong is moved to a heater where any ice and condensation is removed using dry heated compressed air. The procedure for crystal mounting and dismounting is shown schematically in Figure 5.

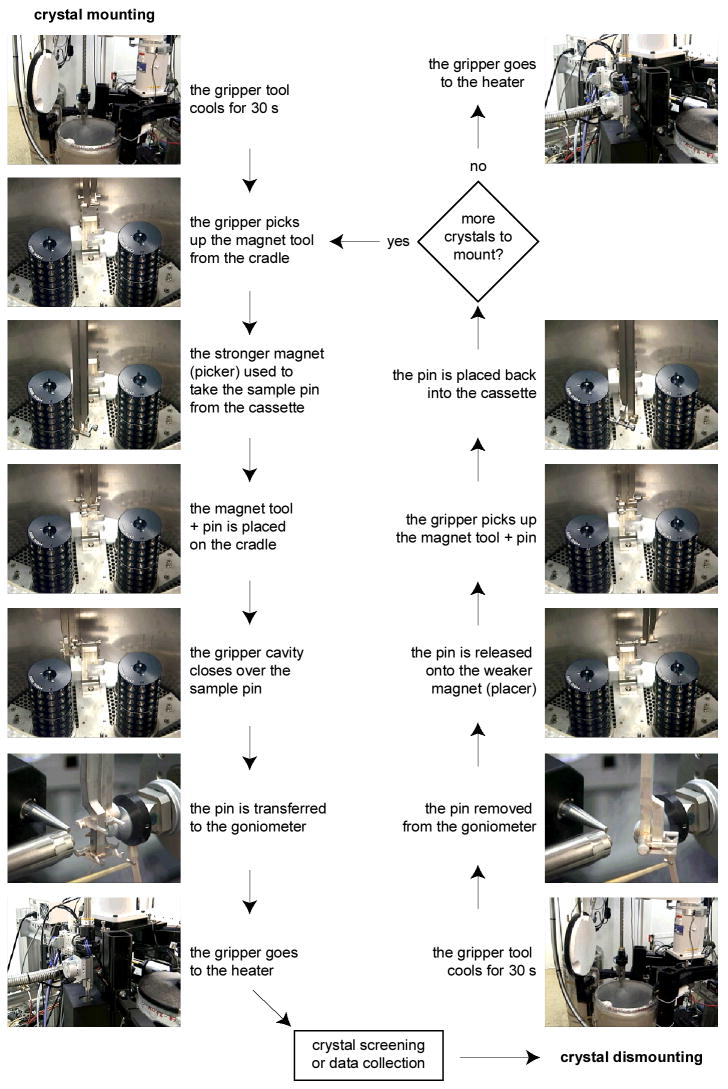

Figure 5.

Flow diagram showing the steps involved in sample mounting (left) and dismounting (right).

Tools developed at SSRL are available to experimenters to assist with manual loading of crystals into the sample cassettes, and with shipping cassettes to SSRL in preparation of the synchrotron experiment.6 The cassette, with transfer handle attached, is laid within cassette loading dewar making the all 96 ports available for filling by simply rotating the cassette to bring the desired row of ports to the top. A slotted loading alignment tool is also supplied, along with a magnetic wand for manipulations of the sample pins. For shipping and storage, two cassettes fit within the sample canister of standard models of dry-shipping dewars including the Taylor-Wharton CP-100 and CX-100, and the MVE SC 4/2 V. When just one cassette is shipped, a styrofoam spacer is used to keep it secure and prevent the cassettes from sliding up and down within the dewar should it inadvertently become inverted. This spacer, a large aperture dry-shipper canister, and canister support ring are part of the standard cassette tool kit. Full instructions for the use of the tools, and guidelines for sample preparation and mounting, are given on the SSRL Structural Molecular Biology webpage.7

User Interface

Software control at the SSRL PX beamlines is managed using a Distributed Control System (DCS) and the graphical user interface, Blu-Ice which have been described previously3. Driver software for robot operation, that was developed in C++ using the SPEL+ libraries supplied by Epson, has been integrated into the DCS enabling the robot to be coordinated with the motion of other beamline hardware. The Blu-Ice interface allows full control over the all aspects of the PX experiment, giving the experimenter access to the SAM system with the ability to rapidly set up fully automated screening runs or mount and dismount samples individually.

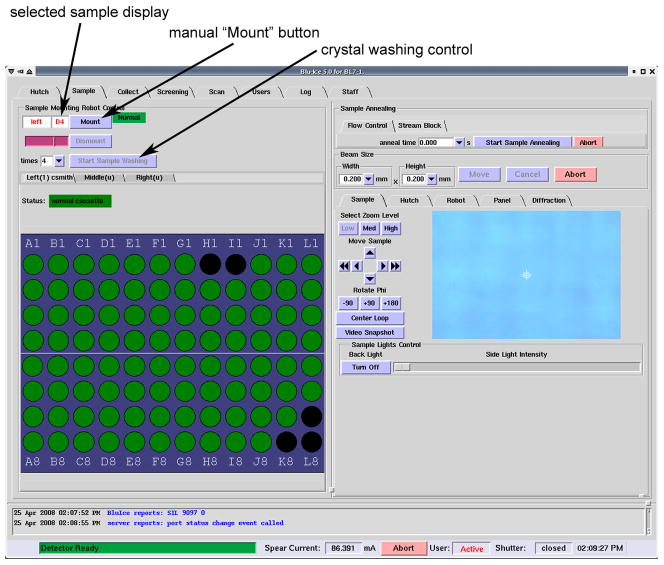

The Sample interface (Figure 6) is designed for experimenters who have only a few crystals to screen or already know which crystals to use for data collection. The array of circles at the lower left represents the 96 ports in a sample cassette. The port where the crystal of interest is located can be selected from the array and the small box next to the “Mount” button becomes populated with the port number. Alternatively, the port number can be typed into this box. Clicking on the “Mount” button then instructs the robot to mount this sample from this cassette to the goniometer. The control system automatically dismounts any previously mounted sample. After mounting a sample, the standard tabs in Blu-Ice (Hutch, Collect and Scan) can be used to select experimental parameters, measure absorption edges and collect diffraction images. The “Dismount” button can be used to remove the sample from the goniometer and return it to the cassette.

Figure 6.

Screenshot of the Sample Tab from the Blu-Ice software. The array at lower left allows the experimenter access to all 96 ports in a chosen cassette, and the “Mount” button at the top left can then be used to instruct the SAM to mount a particular sample.

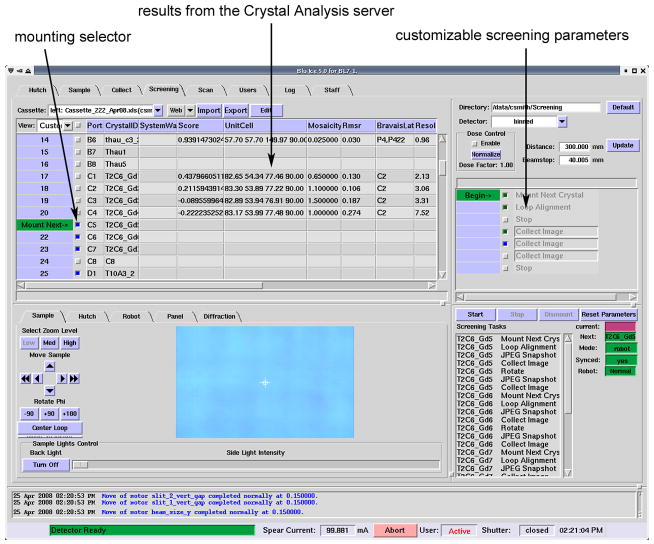

The Screening interface (Figure 7) gives the experimenter the ability to automatically screen a large number of samples. A spreadsheet containing a list of sample names, cassette ports, subdirectory name and filename root structure, is first uploaded into the Blu-Ice interface. A convenient web-based interface is available for uploading this information to SSRL before the experimenter arrives, since the spreadsheet is often generated by the experimenter prior to beam time, as the cassette is being filled. The next stage involves the selection of samples to be screened. All the samples in a cassette can be selected by clicking the small box at the very top of the spreadsheet to the left of “Port”. The boxes beside each sample will turn blue indicating that sample has been picked. In addition, each sample can be individually selected and deselected by clicking the appropriate small box. By clicking the cursor on the crystal number in gray on the extreme left, a “Mount Next” icon can be positioned anywhere in the spreadsheet and this will indicate the first crystal to be mounted. The crystals will be mounted and screened sequentially after this. The third stage involves the definition of the screening parameters to be applied to each sample, and this is selected in the widget at top right. Customizable parameters include: directory information, detector and beamstop distance, the number of images to collect, oscillation angle and x-ray exposure time (the latter two are accessed by hovering the cursor over the “Collect Image” window). The widget at the lower right shows the upcoming screening tasks and updates automatically if the sample selection is changed or the screening parameters are altered.

Figure 7.

Screenshot of the Screening Tab from the Blu-Ice software. The spreadsheet at top left has been loaded by the experimenter, and during initial screening the Crystal Analysis server updates the table with results as shown.

Screening is initiated with the “Start” button at center right. The first step is the mounting of the first crystal selected in the spreadsheet, followed by automated loop alignment which is always carried out. A JPEG video image of loop-centered sample is automatically saved in the experimenter’s directory for inspection and the diffraction images are then measured. At any time the system may be stopped to allow manual inspection of the results before proceeding. For this purpose, a live video image of the sample with a ‘click to center’ capability is also available (lower left). While the system is screening, the experimenter can use the interface to track progress by following intuitively displayed arrows on the spreadsheet and the screening parameter widget, and by indicator boxes and the list of steps to be performed in the screening tasks widget. Through an external Crystal Analysis server,8 screening results are automatically scored and, for crystals which are indexable, a data collection strategy is determined. The results, including the cell parameters, Bravais lattice, predicted resolution, estimated mosacity, and the rms fit from MOSFLM9 are displayed in the spreadsheet, along with an overall score for the crystal (Figure 7). These parameters can then be used to determine the crystals most suitable for full data collection. Following screening, the experimenter can then remount the best quality crystals using the robot, and collect X-ray diffraction data. A sample queuing interface is currently under development which will enable experimenters, following screening, to setup data collection runs from multiple crystals which will proceed sequentially in an automated fashion.

It was observed by members of JCSG that the passage of a crystal through the liquid nitrogen dewar during mounting and dismounting sometimes resulted in the removal of accumulated ice from the surface of the crystal. In some instances, severe ice-rings were observed from a given sample when it was initially mounted during screening, but when it was remounted at a later date, it was found that the majority of the ice had been removed. The removal of accumulated frost is typically accomplished by manually pouring liquid nitrogen over the sample when mounted on the goniometer. Washing is also commonly carried out by moving the sample rapidly in a liquid nitrogen bath. Automated sample washing has been implemented in Blu-Ice using the SAM system, which mimics this later procedure. The sample is removed from the goniometer, placed on the magnet tool inside the dispensing dewar, washed, and returned. The controls for sample washing are accessible to the experimenter from the Blu-Ice Sample interface and include an option to choose the number of washing cycles (Figure 6).

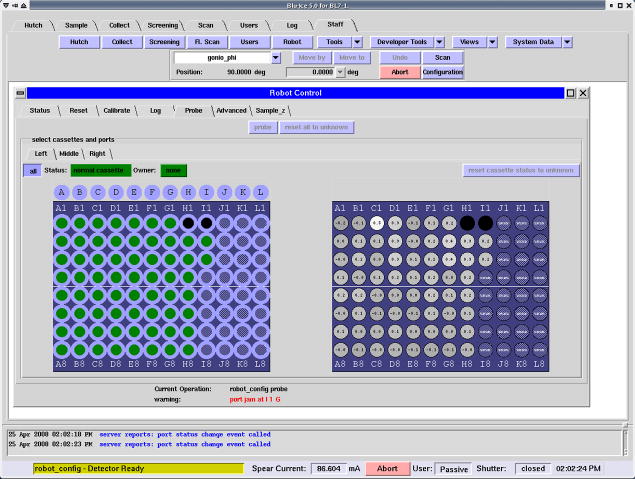

In order to simplify maintenance of the SAM system for support staff, a graphical user interface was designed and integrated in Blu-Ice (Figure 8). This intuitive interface simplifies maintenance, facilitates rapid diagnosis and recovery of system failures, and provides a single location for staff to check the robot’s overall status, give feedback on several vital parameters including low liquid nitrogen levels and the status of the hutch door, provide for manual control over robot actuators, and allow for the modification of system tolerances. Algorithms are provided which allow staff to perform routine tasks, such as automated calibration, or system resets, in a consistent step-by-step manner. The ATI force sensor plays a critical role in hardware calibration. The positions of the magnet post, cassettes, goniometer, and transfer tongs are automatically calibrated to within 50 μm. During normal operation, automatic calibration checks of the XYZ position of the goniometer are performed using laser displacement sensors to ensure the dismounting position is the same between samples. Another important tool for staff includes the ability to ‘probe’ an experimenter’s cassette to determine if ports contain properly inserted pins (Figure 8). The pin positions are checked with the dumbbell tool and if they are above or below a certain threshold, the pin is flagged and is disabled in the spreadsheet and cannot be mounted. Whenever the dispensing dewar lid is manually opened, verification routines will ensure that the cassette is actually present and that it is sitting correctly before resuming regular operations. These procedures have dramatically simplified the training and reduced the effort required to support and maintain the SAM system, making it possible for SSRL support staff to offer SAM to all general experimenters as a standard beamline component in 2005. There is also the option to have the cassettes of up to three different experimenters mounted on the beam line at the same time. The different experimenters can then be enabled sequentially over a given shift or over a weekend, thus maximizing the use of the beam line without requiring physical intervention from SSRL staff. In this case, security features prevent one experimenter from accidentally mounting crystals from a cassette belonging to another research group.

Figure 8.

Screenshot of the Robot Control interface from the Blu-Ice software. The experimenter’s cassette(s) are initially “probed” by the robot and the results displayed in two 12×8 arrays. The array on the left show the presence (green circle) or absence (black circle) of samples in the given ports. The grey circles indicate ports which the robot has yet to probe. The array on the right gives staff an indication of the “force” measured by the ATI force sensor, which allows for the identification of any problem samples.

Given the high degree of automation now available at the SSRL PX beamlines, the next logical step has been to create tools necessary for fully remote access to the experimental stations.10 Experimenters send their samples in SSRL cassettes or uni-pucks to SSRL where beamline staff place them in the robot dewar; it takes approximately 5 seconds to transfer a cassette from a shipping dewar to the beamline dispensing dewar. The remote experimenter then connects to the SSRL computer systems through a small client installed on their local systems, which emulates the computer environment on the beamline computers. At this stage remote control of the beamline becomes indistinguishable from local control. During the 2007 experimental run, 75% of the SSRL protein crystallography experimenters took advantage of this remote access capability.

Conclusions

The Stanford Auto-Mounting (SAM) system has been used to screen over 185,000 crystals for diffraction quality in total. During the first half of 2008, SAM was used to mount more than 40,000 samples. Approximately 1,000 of these were stored in uni-pucks, a storage container designed to be compatible with a variety of robotic mounting systems currently in use at synchrotrons in the United States. As the availability of robotic sample mounting systems increases at synchrotron sources and home labs, we expect the use of uni-pucks to become more popular possibly surpassing the use of cassettes. The SAM system has a significantly greater capacity compared to other synchrotron-based and commercially available robotic mounting systems since a maximum of 288 samples can be placed in the robot dewar, mounted by the robot and screened without requiring user intervention or entry into the beamline end-station (see ref. 4 for an exhaustive listing of the other systems and their capacities). Furthermore, since the system is based primarily on off-the-shelf parts, with only minor in-house manufacturing required, it is an easy and inexpensive system to install and, as noted, has been readily adopted at five other synchrotron laboratories.

To meet user demand we plan to make a number of improvements to the SAM system. These include fabricating a larger dispensing dewar which would hold 6 cassettes (or 24 uni-pucks in adaptor cassettes) and decreasing the robot cycle time through a number of hardware and software upgrades. For example a faster sample rotation stage and better video analysis software will decrease the time required for automated sample loop centering and a more efficient tong drier and in-hutch humidity control system will decrease the time necessary to remove condensation from the robot tongs.

SAM is a proven technology and coupled with the performance of the new SPEAR3 source enables highly efficient crystal screening and data collection for protein crystallography experiments. SAM is currently available on all six SSRL macromolecular crystallography beamlines and enables a fully remote mode for carrying out crystallography experiments. During the 2007 experimental run, over 85% of all macromolecular crystallography experiments at SSRL used SAM. The SAM system has been installed at several synchrotron beam lines worldwide including the Advanced Light Source (12.3.1), Australian Synchrotron (BL1), Canadian Light Source (CMCF-1), National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (BL13B1 & BL13C1), and at the Photon Factory (BL-5A, BL-17A & AR-NW12A).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the entire SAM development team that includes members of the Joint Center for Structural Genomics and the SSRL Structural Molecular Biology group. Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory operations funding is provided by the US Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences that supports our Joint Center for Structural Genomics (JCSG) collaboration.

Biography

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lesley SA, Kuhn P, Godzik A, Deacon AM, Mathews I, Kreusch A, Spraggon G, Klock HE, McMullan D, Shin T, Vincent J, Robb A, Brinen LS, Miller MD, McPhillips TM, Miller MA, Scheibe D, Canaves JM, Guda C, Jaroszewski L, Selby TL, Elsliger MA, Wooley J, Taylor SS, Hodgson KO, Wilson IA, Schultz PG, Stevens RC. Structural genomics of the Thermotoga maritima proteome implemented in a high-throughput structure determination pipeline. PNAS. 2002;99:11664–11669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142413399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen AE, Ellis PJ, Miller MD, Deacon AM, Phizackerley RP. An automated system to mount cryo-cooled protein crystals on a synchrotron beamline, using compact sample cassettes and a small-scale robot. J Appl Cryst. 2002;35:720–726. doi: 10.1107/s0021889802016709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McPhillips TM, McPhillips SE, Chiu HJ, Cohen AE, Deacon AM, Ellis PJ, Garman E, Gonzalez A, Sauter NK, Phizackerley RP, Soltis SM, Kuhn P. Blu-Ice and the Distributed Control System: software for data acquisition and instrument control at macromolecular crystallography beamlines. J Synchrotron Rad. 2002;9:401–406. doi: 10.1107/s0909049502015170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.http://smb.slac.stanford.edu/robosync/

- 5.Pflugrath JW. Macromolecular cryocrystallography - methods for cooling and mounting protein crystals at cryogenic temperatures. Methods. 2004;34:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.http://www.crystalpositioningsystems.com

- 7.http://smb.slac.stanford.edu/users_guide

- 8.González A, Moorhead P, McPhillips SE, Song J, Sharp K, Taylor JR, Adams PD, Sauter NKSMS. Web-Ice: Integrated data collection and analysis for macromolecular crystallography. J Appl Cryst. 2008;41:176–184. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leslie AGW. Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Jnt CCP4/ESF-EACMB Newsl Protein Crystallogr. 1992;26 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soltis SM, Cohen A, Deacon A, Eriksson T, Gonzalez A, McPhillips S, Chui J, Dunten P, Hollenbeck M, Mathews I, Miller M, Moorhead P, Smith C, Song J, van den Bedem H, Ellis P, Kuhn P, McPhillips T, Phizackerley P, Sharpe K, Wolff G. New Paradigm for Macromolecular Crystallography Experiments: Automation and Remote Data Collection. 2008 doi: 10.1107/S0907444908030564. In preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]