SUMMARY

Meiosis is coupled to gamete development and it is well regulated to prevent aneuploidy. During meiotic maturation, Drosophila oocytes progress from prophase I to metaphase I. The molecular factors controlling meiotic maturation timing, however, are poorly understood. Here we show that Drosophila α-endosulfine (endos) plays a key role in this process. endos mutant oocytes have a prolonged prophase I and fail to progress to metaphase I. This phenotype is similar to that of mutants of cdc2 (synonymous with cdk1) and of twine, the meiotic homolog of cdc25, which is required for Cdk1 activation. We found that Twine and Polo kinase levels are reduced in endos mutants, and identified Early girl (Elgi), a predicted E3 ubiquitin ligase, as a strong Endos-binding protein. In elgi mutant oocytes the transition into metaphase I occurs prematurely, but Polo and Twine levels are unaffected. These results suggest that Endos controls meiotic maturation by regulating Twine and Polo levels and, independently, by antagonizing Elgi. Finally, germline-specific expression of the human α-endosulfine ENSA rescues the endos meiotic defects and infertility, and α-endosulfine is expressed in mouse oocytes, suggesting potential conservation of its meiotic function.

Keywords: meiosis, oogenesis, α-endosulfine, Cdc25, Polo, E3 ubiquitin ligase, Drosophila

INTRODUCTION

Meiosis is a fundamental process required for gamete production. Oocytes undergo two meiotic arrests to accommodate their growth and differentiation (Kishimoto, 2003; Page and Orr-Weaver, 1997; Sagata, 1996; Whitaker, 1996). The prophase I arrest is highly conserved, while the second block in metaphase I or II is species-specific. The prophase I arrest lasts for prolonged periods, even decades in humans. In response to hormonal and/or developmental cues, this arrest is released and meiosis progresses to metaphase I, a process known as meiotic maturation. The precise timing of meiotic maturation ensures normal chromosome segregation and viable oocytes.

In Drosophila melanogaster, each oocyte develops within a germline cyst that includes fifteen nurse cells, and follicle cells surround each cyst to form an egg chamber, which develops through fourteen stages (Spradling, 1993). The oocyte initiates meiosis following cyst formation and remains in prophase I for days (King, 1970). During prophase I, chromosomes become condensed into a spherical karyosome, with a spot of concentrated heterochromatin. Meiotic maturation occurs during stage 13; the nuclear envelope breaks down, chromosomes condense and the meiotic spindle is assembled, culminating in the second meiotic arrest in metaphase I (King, 1970). Metaphase I is marked by a bipolar meiotic spindle, exchange chromosomes positioned at the metaphase plate and small non-exchange, highly heterochromatic fourth chromosomes localized between the metaphase plate and the poles (Theurkauf and Hawley, 1992). Mature stage 14 oocytes remain in metaphase I and dehydrate. In the oviduct, water re-absorption is thought to promote completion of meiosis (Mahowald et al., 1983).

In several systems, high activity of the serine/threonine kinase Cdk1 (also known as Cdc2) and its regulatory subunit CyclinB are required for meiotic maturation (Kishimoto, 2003; Sagata, 1996). Cdk1 activity is stimulated by the Cdc25 phosphatase, which removes inhibitory phosphates on Cdk1. CyclinB/Cdk1 activity is low during prophase I, while an activity increase triggers meiotic maturation via the phosphorylation of factors involved in nuclear envelope breakdown, chromosome condensation and spindle assembly (Kishimoto, 2003). Although much less is known about Drosophila meiotic maturation, in mutants of twine, the germline-specific cdc25 homolog, oocytes do not progress to a normal metaphase I (Alphey et al., 1992; Courtot et al., 1992; White-Cooper et al., 1993), suggesting that high Cdk1 activity is likewise required here. In addition, CyclinB dynamically associates with the meiotic spindle in Drosophila, indicating a potential role in spindle organization (Swan and Schupbach, 2007).

Multiple mechanisms ensure low Cdk1 activity during prophase I in Drosophila. The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) induces cyclin degradation (Vodermaier, 2004). In female-sterile mutants of morula, which encodes the APC/C subunit APC2, CyclinB accumulates in germline cysts leading to nurse cell arrest in a metaphase-like state (Kashevsky et al., 2002; Reed and Orr-Weaver, 1997). Cyclin translational repression by Bruno, encoded by arrest, also contributes to low Cdk1 activity during prophase I, and arrest mutant cysts accumulate Cyclins A and B (Sugimura and Lilly, 2006). High levels of Dacapo, a Cdk1 inhibitor, within the oocyte likely contribute to the prophase I arrest (Hong et al., 2003). It is much less understood how these repressive mechanisms are alleviated or how meiotic maturation timing is precisely controlled.

α-Endosulfines are small phosphoproteins of largely unknown functions. Studies of mammalian α-endosulfines in culture suggested a possible role in insulin secretion (Bataille et al., 1999); however, this has not been demonstrated in vivo. Moreover, the expression of α-endosulfines in many tissues (Heron et al., 1998) suggests that they play multiple roles. Our previous studies showed that Drosophila α-endosulfine (endos) is required for normal oogenesis rates, stage 14 oocyte dehydration, and fertility (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2004). Here we demonstrate for the first time in any system that endos is required for meiotic maturation. endos mutant oocytes have delayed nuclear envelope breakdown and fail to progress into metaphase I. This defect is remarkably similar to that of twine and cdc2 mutants, and endos mutants have reduced expression of Twine and Polo kinase, another cell cycle regulator. In an in vitro binding screen, we identified Early girl (Elgi), a predicted E3 ubiquitin ligase, as a strong Endos interactor. elgi disruption results in premature transition from prophase I to metaphase I, although it does not rescue Twine or Polo levels in endos mutants. We propose that Endos promotes expression of Polo and Twine post-transcriptionally and has a separate role via inhibition of Elgi to promote meiotic maturation. Remarkably, germline-specific expression of ENSA, the human α-endosulfine, rescues the endos meiotic defect and α-endosulfine is expressed in mouse oocytes, suggesting conservation of the meiotic function of α-endosulfine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila strains and culture

Fly stocks were maintained at 22–25°C on standard medium. yw was a control. endos00003, endosEY01105, twe1, cdc2E1–24, and cdc2B47 alleles have been described (Alphey et al., 1992; Courtot et al., 1992; Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2004; Stern et al., 1993; White-Cooper et al., 1993). cdc2E1–24/cdc2B47 females raised at 18°C were analyzed after 29°C incubation for 1–2 days. The P-element insertion EY10782, 396 bp upstream of the elgi coding sequence, was mobilized to generate deletions. The elgi1 deletion removes the first two exons, and elgi2 removes 54 base pairs of the coding region (see Fig. 4D). twe::lacZ, UASp-polo, nanos-Gal4::VP16, and tGPH have been described (Britton et al., 2002; Edgar and O'Farrell, 1990; Santel et al., 1998; Van Doren et al., 1998; Xiang et al., 2007). twe::lacZ is a genomic construct modified to express a Twe::β-galactosidase (Twe-β-gal) protein fusion (White-Cooper et al., 1998). Other genetic elements are described in Flybase (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu).

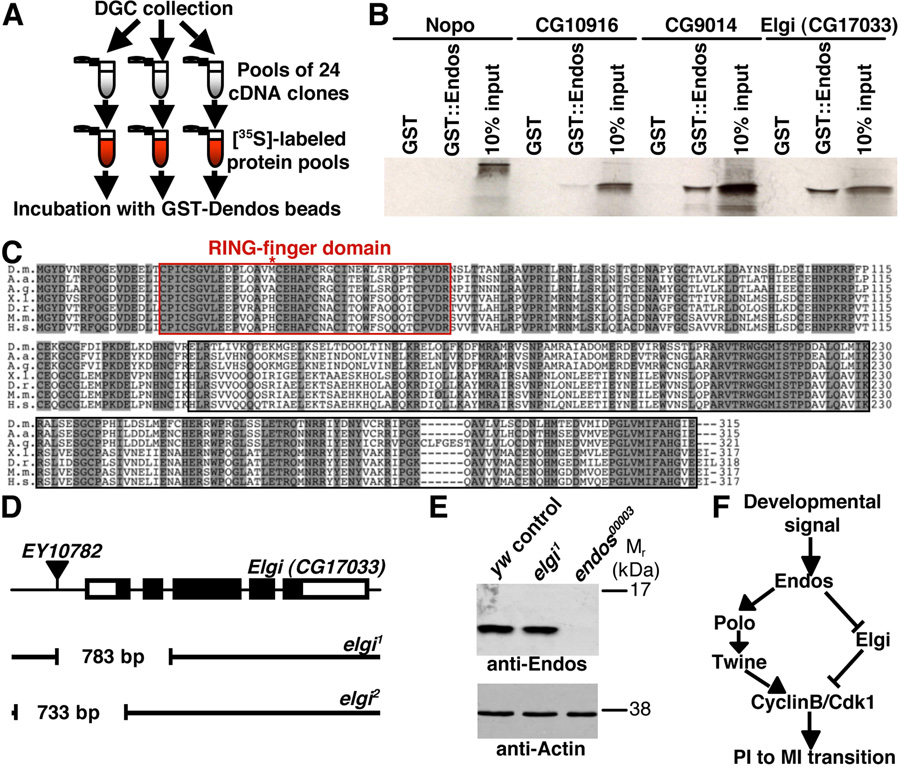

Figure 4. Endos binds to a putative E3 ubiquitin ligase encoded by elgi.

(A) DIVEC screen used to identify Endos interactors. (B) Autoradiogram showing that the GST::Endos fusion protein specifically binds to the closely related CG9014 and Elgi E3 ubiquitin ligases but not to more distant E3s, such as Nopo and CG10916. (C) Elgi shares 81%, 80%, 57%, 57%, 56%, and 54% amino acid identity with the A. aegypti, A. gambiae, X. laevis, D. rerio, M. musculus, and H. sapiens homologs, respectively. Red box marks RING domain. Shaded amino acid residues represent identities. Asterisk indicates the first methionine for predicted Elgi2 protein. (D) elgi alleles generated by imprecise excision of EY10782. Thick bars represent elgi exons (coding region in black). Gaps in black lines indicate deleted regions in elgi1 and elgi2. (E) Western showing normal Endos levels in elgi1 ovaries. Actin used as loading control. (F) Model for the role of Endos in oocyte meiotic maturation. Endos controls Polo kinase and, perhaps indirectly, Twine levels, leading to activation of CyclinB/Cdk1. By binding and inhibiting Elgi, Endos may have a parallel role in refining the timing of meiotic maturation.

To assess endos00003 egg fertilization, we used dj-GFP males (Santel et al., 1997). All eggs were fertilized, as detected by the presence of GFP-positive sperm. Oocyte dehydration was analyzed as described (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2004).

Transgenic line generation

The endos coding region plus 21 base pairs immediately upstream were subcloned into UASpI (modified from pUASp, T. Murphy) to create pUASp-endos. Similarly, the ENSA plus the same upstream 21 base pairs from endos were used to generate pUASp-ENSA. The twine coding region was subcloned into pCS2 (modified UASp vector; E. Lee) in frame to the a c-Myc tag to generate UASp-myc::twe. For hs-twe, the twine cDNA was subcloned into pCasper-hs. Transgenic lines were generated as described (Spradling and Rubin, 1982).

RNA and protein analysis

For western analysis, ovaries or egg chambers were homogenized, electrophoresed and transferred to membranes as described (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2004). Membranes were blocked with Odyssey Blocking Reagent (LI-COR Biosciences) and probed with 1:100 rabbit polyclonal anti-β-galactosidase (Cappel), 1:50 mouse monoclonal anti-Actin (JLA20, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), 1:10 mouse monoclonal α-CyclinB (F2F4, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), 1:1,000 rabbit polyclonal α-Endos (c302) (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2004), 1:80 mouse monoclonal anti-Polo (MA294) (Logarinho and Sunkel, 1998), 1:500 MPM2 mouse monoclonal (Upstate), 1:1,000 mouse monoclonal anti-c-Myc (9E10, Sigma), or 1:1,000 mouse monoclonal anti-Cdk1 (anti-PSTAIR, Sigma) antibodies. Alexa 680-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse (Molecular Probes) and IRDye 800-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig (Rockland) secondary antibodies were used at 1:5,000 dilution. The Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) was used for detection.

Ovarian RNA extracted using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen) was reverse transcribed (RT) using Oligo(dT)16 (Applied Byosystems) for priming and SuperScript™ II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). PCR was performed using undiluted or diluted (1:5 and 1:25) RT reactions.

Immunoprecipitation/Kinase assay

Immunoprecipitation/Cdk1 kinase assays were performed as described (Gawlinski et al., 2007) using extracts from 200 homogenized stage 14 oocytes per sample. Briefly, following incubation of 10 µl of extract with 0.5 µl of anti-Cdk1 (Gawlinski et al., 2007) or 2.5 µl of anti-CyclinB antibodies, immunocomplexes were isolated using proteinA- or proteinG-sepharose beads. Washed beads were incubated with 16 µl of kinase buffer, 3 µM of histone H1.2, and 2 µCi [32P] ATP for 10–20 minutes at 25°C. Detection and quantification were performed using a Typhoon 9200 Imager and ImageQuant 5.2. Parallel immunoprecipitations using 100 µl of extract and 5 µl of rabbit polyclonal anti-Cdk1 or 25 µl of anti-CyclinB antibodies were subjected to western blotting and quantified using Image J. Average relative intensities of [32P]-histone H1 were determined after normalization for immunoprecipitated protein amounts, with control levels arbitrarily set at 1.00.

Immunostaining and microscopy

For oocyte DNA analyses, ovaries were dissected in Grace’s insect medium (Life Technologies) and fixed as described. Samples were incubated in 0.5 µg/ml DAPI for 10 minutes, mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories), and analyzed using a Zeiss Axioplan 2. Egg chamber developmental stages were identified as described (Spradling, 1993), but we further subdivided stage 13 as early (11–13 nurse cell nuclei), mid (6–10 nurse cell nuclei), and late (1–5 nurse cell nuclei). Stage 13 and 14 oocyte nuclear envelopes were visualized by differential interference contrast and epifluorescence microscopy. Results were subjected to Chi-square test.

For visualization of microtubules, ovaries were dissected in Robb’s media and fixed in 2X oocyte fix buffer as described (Theurkauf and Hawley, 1992). Stage 14 oocytes were hand dechorionated using dissecting needles (Precision Glide- size 27G 11/4), extracted in 1% PBT and stained with anti-α-tubulin-FITC conjugated antibody (DM1A clone, Sigma) at 1:200 dilution. Washed samples were treated with RNAse A and stained with propidium iodide. For visualization of DNA and spindles during embryonic mitoses, 0–3 hour embryos were collected, dechorionated, and shaken vigorously for 2 minutes in 1:1 heptane:methanol. After three washes in methanol, samples were fixed overnight at 4°C in 1 ml of methanol, blocked in PBT plus 5% normal goat serum and 5% bovine serum albumin, stained with anti-α-tubulin-FITC antibody, and analyzed using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope.

For X-gal staining, ovaries were dissected in Grace’s insect medium, fixed, and stained at 37°C for 20–30 minutes as described (Margolis and Spradling, 1995). Samples were mounted and analyzed using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope.

Live imaging

Ovaries were dissected in halocarbon oil 700 (Sigma). Stage 13 egg chambers were injected with 1:20 OliGreen dye (Invitrogen) and 2 mg/ml rhodamine-labeled tubulin(Cytoskeleton, Inc.). Images were obtained at 20 second intervals using a Leica TCS SP5 inverted confocal microscope and assembled using Image J. Nuclear envelope breakdown duration was measured as the elapsed time from beginning of nuclear envelope ruffling until entry of tubulin into nucleus.

Drosophila in vitro expression cloning (DIVEC) binding screen

For the DIVEC binding screen, we used the first release of the Drosophila Gene Collection as described (Lee et al., 2005). Briefly, 24-cDNA pools were converted into radiolabeled protein pools. Recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST)-Endos fusion protein beads were incubated with 1.5 µl of each pool in Buffer A (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 10 µg/ml protease inhibitor cocktail tables, EDTA free [Roche]) at 4°C for 2 hours, and washed 3 times with 2.5 ml of Buffer A and once with 2.5 ml of Buffer B (50mM Tris, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF) in Wizard minicolumns (Promega). Bound proteins eluted in 95°C pre-heated 2X sample buffer were electrophoresed and detected by autoradiography. Five pools with potential Endos-interacting proteins were subjected to secondary (four cDNAs per pool) and tertiary screens (single cDNAs).

Mouse tissue analysis

All mice in the present investigation were housed and used in accordance with the National Institutes of Health and institutional guidelines. Immunohistochemistry of 5 µm-thick Bouin’s-fixed paraffin-embedded ovarian sections was performed as described (Tan et al., 1999), using rabbit pre-immune or anti-Endos c302 serum at 1:1,000 dilution.

RESULTS

endos is required for meiotic maturation

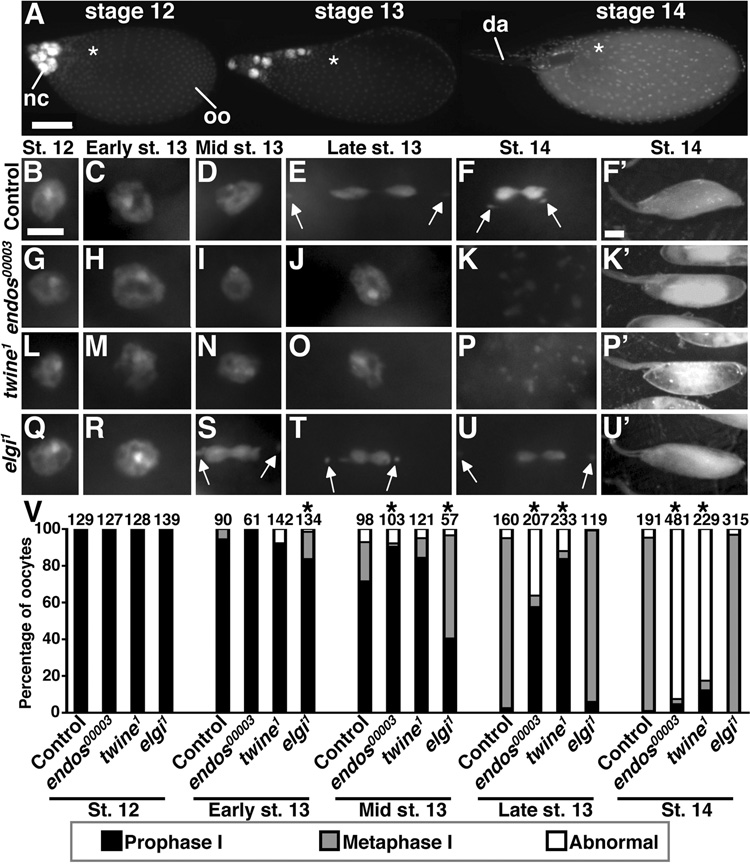

Although mammalian α-endosulfines have been proposed to regulate insulin secretion (Bataille et al., 1999), our evidence suggests that endos does not control the insulin pathway in Drosophila (see Fig. 1 in supplementary material). Nevertheless, Endos is strongly expressed in the germline, and endos00003 females are completely sterile and their stage 14 oocytes fail to dehydrate (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2004). We asked whether meiosis was affected in endos00003 females by visualizing the oocyte DNA morphology with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Fig. 1, see Table 1 in supplementary material). As previously described (King, 1970), wild-type oocytes are in prophase I until stage 12 (Fig. 1B–F,V). In early stage 13, only 5.6% of oocytes have progressed to metaphase I, while in mid stage 13, that percentage increases to 21%; by late stage 13, virtually all oocytes are in metaphase I, and this arrest is maintained in mature stage 14 oocytes. endos mutant oocytes arrest in prophase I, as indicated by the typical nuclear morphology; however, this arrest lasts longer, with 90% of the mid stage 13 and 58% of late stage 13 oocytes still in prophase I (Fig. 1G–K,V). By stage 14, endos00003 oocytes have exited prophase I, but only 3% are in metaphase I. Instead of progressing into metaphase I, 93% of the oocytes display dispersed or visually undetectable DNA. Heteroallelic endos00003/endosEY1105 and hemizygous endos00003/Df(3L)ED4536 females show similar phenotypes (see Table 1 in supplementary material). Endos protein is normally expressed throughout the cytoplasm of ovarian germ cells (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2004), including stage 14 oocytes (J.R.V.S. and D.D.-B., unpublished). Moreover, germline-specific expression of Endos rescues meiotic maturation and fertility in endos00003 females (see Fig. 5C,E,F). These results indicate that endos is required in the germline for oocyte progression from prophase I to metaphase I.

Figure 1. endos00003 oocytes fail to undergo meiotic maturation.

(A) DAPI-stained egg chambers in different stages. nc, nurse cells; oo, oocyte; da, dorsal appendages. Asterisks indicate position of oocyte nucleus. Scale bar, 100 µm. (B–F) Control oocytes in prophase I (B–D) and in metaphase I (E,F). Arrows indicate non-exchange fourth chromosomes. (G–K) endos00003 oocytes have a prolonged prophase I (G–J) and abnormal DNA morphology at stage 14 (K). (L–P) twine1 oocytes show similar phenotypes. (Q–U) elgi1 oocytes in prophase I (Q,R) and in premature metaphase I (S–U). Scale bar, 5 µm. Control (F’) and elgi1 (U’) have dehydrated stage 14 oocytes. endos00003 (K’) and twine1 (P’) oocytes are non-dehydrated and have abnormal yolk. Scale bar, 100 µm. (V) Quantification of DNA morphology. Number of oocytes analyzed shown above bars. Asterisks, P<0.001.

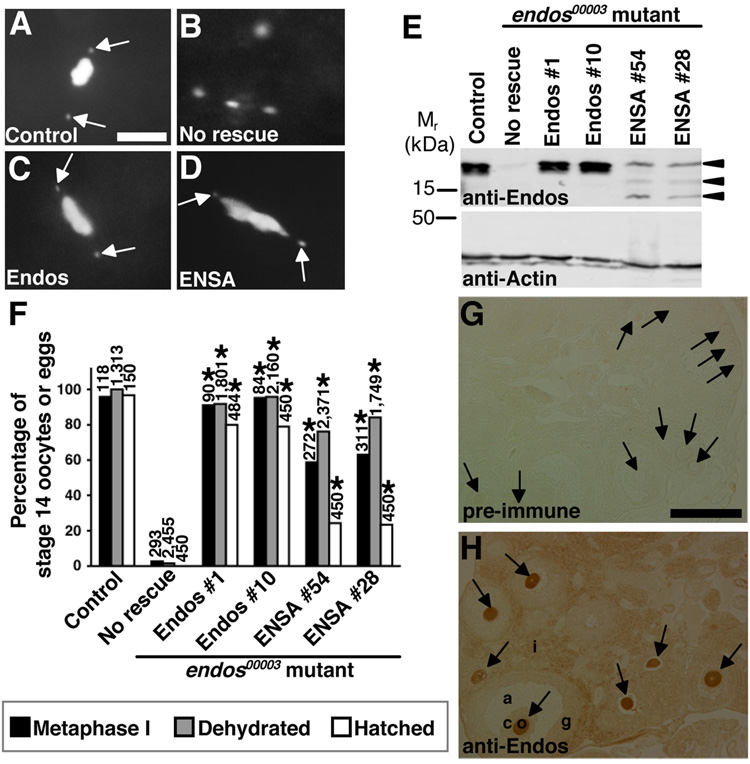

Figure 5. The function of α-endosulfine may be evolutionarily conserved.

(A–D) DAPI-stained stage 14 oocytes from control and endos00003 females expressing Endos or human α-endosulfine (ENSA). Control oocytes (A) arrested in metaphase I and endos mutant oocytes (B) with dispersed DNA. nanos-Gal4::VP16-driven germline expression of UAS-endos (C) or UAS-ENSA (D) transgenes showing endos rescue. Arrows indicate fourth chromosomes. Scale bar, 5 µm. (E) Western analysis showing ovarian expression of Endos and ENSA in rescued females. Actin used as loading control. Arrowheads indicate ENSA-specific bands (lower bands are likely degradation products), absent in “No rescue” control. (F) Quantification of endos00003 rescue. Number of stage 14 oocytes (metaphase I arrest and dehydration) or eggs (hatch rate) analyzed shown above bars. Asterisks, P<0.001. (G,H) Mouse ovary immunohistochemistry showing that anti-Endos antibodies strongly label the cytoplasm of oocytes (H), while no signal is detected by pre-immune serum (G). o, oocyte (arrows); c, cumulus cells; g, granulosa cells; a, antrum; i, interstitial cells. Scale bar, 200 µm.

Interestingly, the meiotic defects of endos mutant females are reminiscent of defects previously reported for mutants of twine, the meiotic cdc25 homolog (Alphey et al., 1992; Courtot et al., 1992; White-Cooper et al., 1993; Xiang et al., 2007). We examined twine1 mutant females and found that 4.3% of twine1 late stage 13 oocytes show metaphase I arrest, with 84% still in prophase I (Fig. 1L–P,V). At stage 14, 83% of twine1 oocytes show abnormalities similar to those of endos mutants. Hemizygous twine1/Df(2L)RA5 females have similar defects (see Table 1 in supplementary material). In addition, using a temperature-sensitive cdc2 mutant genotype, we also find direct evidence that Cdk1 activity is required for meiotic maturation in Drosophila. At the restrictive temperature (29°C), cdc2E1–24/cdc2B47 oocytes show prolonged prophase I at stage 13 and abnormal DNA morphology at stage 14 (see Fig. 2 and Table 1 in supplementary material). Unfortunately, we could not examine the role of CyclinB in meiotic maturation because it is required earlier role in oogenesis (Wang and Lin, 2005). The similarity between the endos00003, twine1 , and cdc2E1–24/cdc2B47 meiotic defects suggests that endos may regulate the progression from prophase I to metaphase I via the regulation of twine to control Cdk1 activity.

Nuclear envelope breakdown is delayed in endos and twine mutant oocytes

We next asked whether endos mutants have defects in nuclear envelope breakdown, an expected consequence of insufficient Cdk1 activity (Kishimoto, 2003). We used Nomarski optics for nuclear envelope visualization (seeFig. 3 in supplementary material). As expected, wild-type oocytes had intact nuclear envelopes in prophase I, while those in metaphase I did not. Consistent with the prolonged prophase I of twine1 and endos00003 oocytes, the nuclear envelope persisted longer in these mutants. However, although this process was delayed, the nuclear envelope eventually disassembled. These results are consistent with the delayed nuclear envelope breakdown previously reported for twine1 mutants (Xiang et al., 2007). To extend our analyses, we performed live imaging, measuring nuclear envelope breakdown duration as the elapsed time from onset of nuclear envelope ruffling until entry of tubulin into nucleus (see Fig. 4 in supplementary material). In wild-type oocytes, the nuclear envelope disassembled in ~9 minutes (n=3; measured times were 16, 4, and 6 minutes). In contrast, the nuclear membrane disassembled unevenly and more slowly in endos00003 (~72 minutes; n=3; measured times were 40, 65, and 111 minutes) and twine1 (~65 minutes; n=3; measured times were 45, 86, and 63 minutes) oocytes. These findings underscore the similarities between endos and twine mutants, and are consistent with reduced Cdk1 activity.

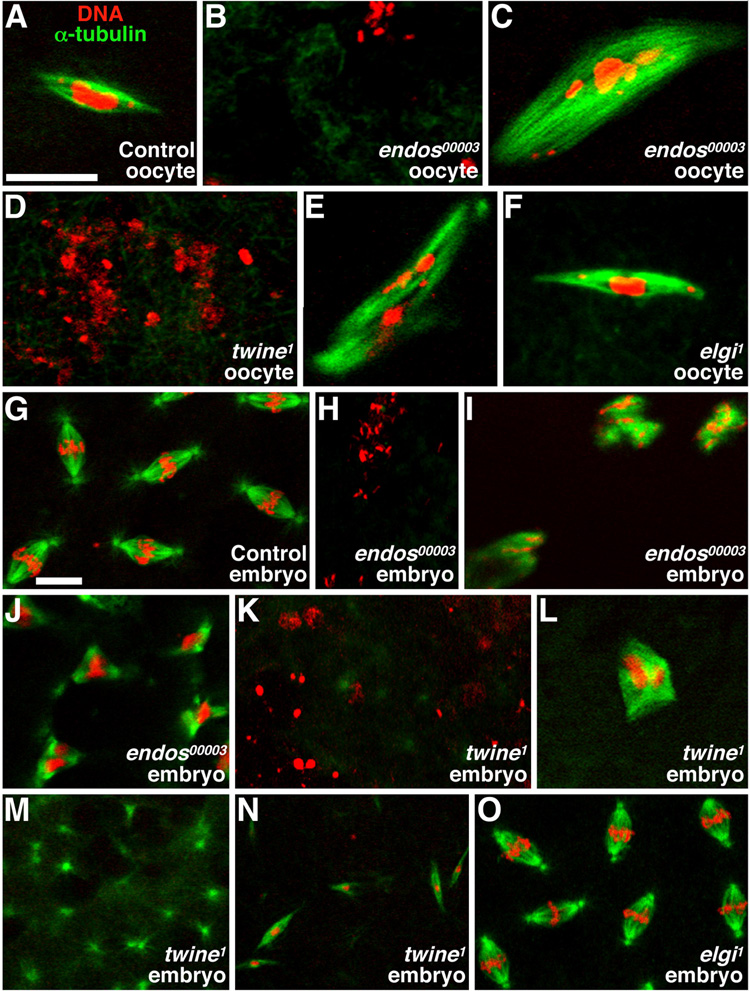

Meiotic spindle formation is abnormal in endos and twine mutant oocytes

High Cdk1 activity induces meiotic spindle formation (Kishimoto, 2003). We thus labeled stage 14 oocytes with anti-α-tubulin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibodies and propidium iodide to visualize microtubules and DNA, respectively (Fig. 2A–F). While 92% (n=25) of control mature oocytes have the typical metaphase I elongated bipolar spindle (Fig. 2A), this is rarely the case in endos or twine mutants. Instead, 87% (n=31) of endos00003 mutants fail to form or maintain the meiotic spindle at stage 14 (Fig. 2B) and a small fraction (13%, n=31) have abnormal spindle-like structures attached to the dispersed DNA (Fig. 2C). Most of twine mutant stage 14 oocytes (82%, n=22) also do not have a meiotic spindle (Fig. 2D); only 7.7% show normal spindle formation, whereas 18% show abnormal spindle masses with DNA attached (Fig. 2E). Live imaging indicated that the spindle either fails to form or fails to be maintained in endos00003 and twine1 oocytes that ultimately lack spindles (J.R.V.S. and D.D.-B., unpublished). These results support the model that endos oocytes have low Cdk1 activity, affecting spindle formation and maintenance.

Figure 2. endos00003 mutants have spindle defects.

Stage 14 oocytes (A–F) and 0–3 hour embryos (G–O) stained with propidium iodide (DNA, red) and anti-α-tubulin (microtubules, green). (A) Control oocytes in metaphase I. (B) Typical endos00003 oocyte showing dispersed DNA without a spindle. (C) Rare endos00003 oocyte showing abnormal DNA associated with large spindle masses. (D,E) Similar twine1 phenotypes. (F) elgi1 oocyte in metaphase I. (G) Control embryos exhibiting typical embryonic mitoses. (H–J) endos00003-derived embryos showing dispersed DNA with no spindle (H), dispersed DNA with spindle masses (I), and tripolar spindles (J). twine1-derived embryos showing dispersed DNA (K), abnormal spindle masses (L), spindle asters with no DNA (M), and long, thin spindles (N). (O) Embryos derived from elgi1 females showing normal spindles and DNA. Scale bars, 10 µm.

Maternal endos is required for syncytial embryonic mitoses

We reasoned that if endos controls meiotic Cdk1 activity, it may have a similar role during early embryonic mitoses. We therefore looked at spindle formation in 0–3 hour embryos derived from endos00003 and twine1 females (Fig. 2G–O). The majority of wild-type embryos (95%, n=95) showed normal mitotic spindles (Fig. 2G). In contrast, 98% (n=51) of endos00003-derived embryos had dispersed (Fig. 2H) or undetectable DNA, resembling the stage 14 oocyte defect. Of those, about 25% had abnormal spindles associated with DNA masses (Fig. 2I). Approximately 2% of endos00003-derived embryos appeared to initiate mitotic divisions, but displayed abnormal bipolar, tripolar or multipolar spindles (Fig. 2J). In accordance with previously reports (White-Cooper et al., 1993), the majority of twine1-derived embryos (96%, n=74) also showed dispersed (Fig. 2K) or undetectable DNA. Half of those had abnormal spindles associated with DNA masses (Fig. 2L), while 8% had free spindle asters (Fig. 2M) and/or thin long spindles (Fig. 2N). These results indicate that early embryonic mitoses are also affected in the small percentage of endos mutants that initiate those divisions.

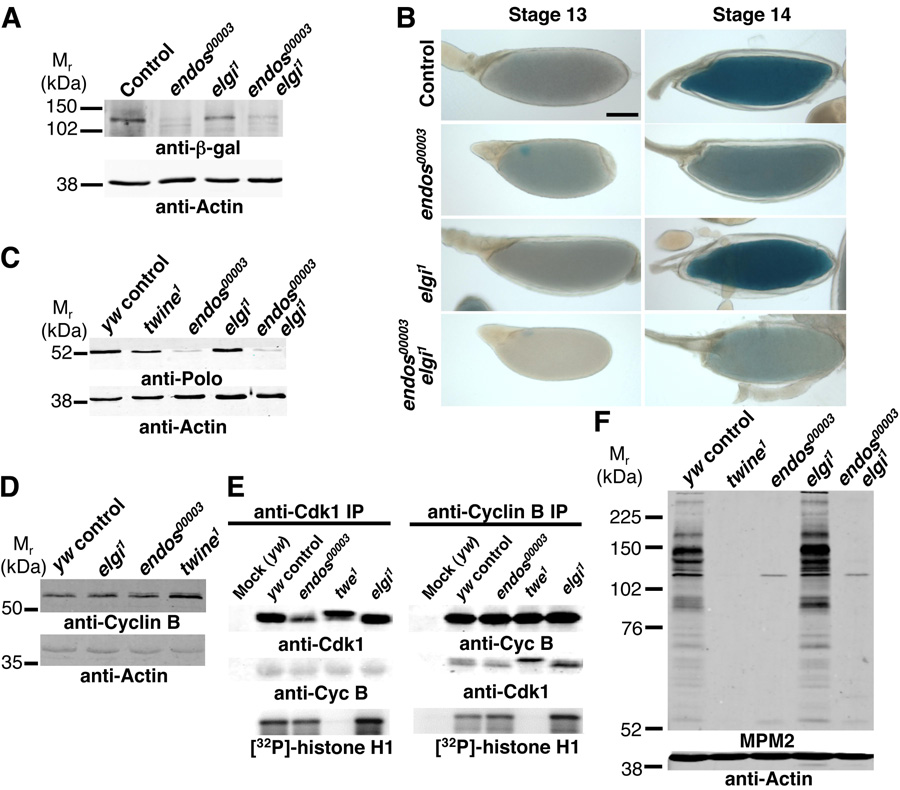

endos controls Twine protein levels

In addition to the similar meiotic defects of dendos00003, twine1 and cdc2E1–24/cdc2B47 oocytes, we found that they also share the oocyte dehydration defect at stage 14 (Fig. 1F’,K’,P’; see Fig. 2H’,L’ in supplementary material). To address whether endos may regulate twine, we examined the levels of a functional Twine::β-galactosidase (Twine::β-gal) fusion protein (Maines and Wasserman, 1999; White-Cooper et al., 1998) in endos mutants. In control and endos00003 ovarioles, Twine::β-gal expression is low or undetectable until stage 12, and detectable at stage 13. At stage 14, however, Twine::β-gal expression is stronger in control but greatly reduced in endos00003 oocytes (Fig. 3A,B), despite normal twine mRNA levels (J.R.V.S. and D.D.-B., unpublished), suggesting that endos is required for Twine upregulation at the post-transcriptional level.

Figure 3. Endos regulates Twine, Polo, and MPM2 phosphoepitopes.

(A) Anti-β-gal western blotting showing reduced expression of Twine::β-gal in endos00003 and endos00003elgi1 stage 14 oocytes. Thirty stage 14 oocytes per lane. (B) X-gal staining (blue) of control, endos00003, elgi1, and endos00003 elgi1 oocytes reflecting Twine::β-gal levels at stages 13 and 14. Scale bar, 100 µm. (C) Polo western analysis of control, twine1, endos00003, elgi1, and endos00003 elgi1 stage 14 oocytes showing strong reduction of Polo in endos00003 and endos00003 elgi1. Fifty stage 14 oocytes per lane. (D) CyclinB western analysis showing normal expression in endos00003 and elgi1 mutants or slightly elevated in twine1 mutants. Thirty stage 14 oocytes per lane. (E) In vitro Cdk1 kinase assay using anti-Cdk1 or anti-CyclinB immunoprecipitates (IP) from control, twine1, endos00003, and elgi1 stage 14 extracts. Mock immunoprecipitates were performed without antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were either immunoblotted using anti-Cdk1 or anti-CyclinB antibodies, or subjected to a kinase assay using [32P]-ATP and histone H1 as substrate. (F) Western blotting using MPM2 antibodies. Wild-type and elgi1 oocytes show high MPM2 levels, while endos00003, twine1 and endos00003 elgi1 oocytes have drastically reduced MPM2 phosphoepitopes. Fifty stage 14 oocytes per lane. Actin used as a control.

We next tested the ability of heat-shock- or Gal4-inducible twine transgenes (hs-twine and UASp-myc::twine, respectively) to rescue the endos00003 defects. Robust expression of Myc-tagged Twine was induced by the germline-specific nanos-Gal4::VP16 driver in control females, and both twine transgenes rescued the meiotic defects and sterility of twine1 females. In contrast, expression of Myc::Twine was severely reduced in endos00003 females, and these low Myc::Twine levels did not rescue the endos00003 defects (see Fig. 5A,B in supplementary material; D.D.-B. and J.R.V.S., unpublished). The endos00003 phenotype was similarly not rescued by the hs-twine transgene (D.D.-B. and J.R.V.S., unpublished). These data suggest that Endos affects Twine protein stability, although we cannot definitively conclude that this causes the endos meiotic defects.

Endos regulates Polo kinase levels independently of Twine

The Xenopus polo-like kinase Plx1 phosphorylates and activates Cdc25, leading to CyclinB/Cdk1 activation (Kumagai and Dunphy, 1996; Qian et al., 2001). In mice, CyclinB/Cdk1-mediated phosphorylation stabilizes Cdc25A and Cdc25B, creating a positive feedback loop (Mailand et al., 2002; Nilsson and Hoffmann, 2000). We therefore asked whether Polo kinase was affected in endos mutants, potentially explaining their low Twine levels. Strikingly, Polo kinase expression was markedly reduced in endos00003 ovaries and mildly reduced in twine1 ovaries (Fig. 3C; see Fig. 6 in supplementary material), although polo mRNA expression was unaffected in endos00003 oocytes (D.D.-B. and J.R.V.S., unpublished), indicating a posttranscriptional effect. The reduced levels of Polo kinase and Twine in endos mutants are not due to a generalized effect on protein expression, as they show no decrease in CyclinB (Fig. 3D), but it is conceivable that Twine is unstable as a consequence of reduced Polo levels. Although germline induction of a functional UAS-polo (Xiang et al., 2007) increased Polo expression in control ovaries, Polo levels remained very low in endos00003 oocytes and endos defects were not rescued (see Fig. 5C,D in supplementary material). Thus, we could not determine if Polo expression is sufficient to rescue the endos defects.

endos00003 oocytes show normal in vitro Cdk1 kinase activity but reduced in vivo MPM2 phosphoepitopes

The low Polo and Twine levels may lead to reduced Cdk1 activity in endos00003 oocytes. To address this question, we first performed immunoprecipitation/Cdk1 kinase assays. In control stage 14 oocytes, anti-Cdk1 immunoprecipitates contained Cdk1 and associated CyclinB, and they phosphorylated histone H1 in vitro (arbitrary relative intensity[R.I.]=1.00, n=9) (Fig. 3E). Similar results were obtained with anti-CyclinB immunoprecipitates, suggesting that stage 14 oocytes contain active CyclinB/Cdk1 complexes. twine1 immunoprecipitates had markedly reduced kinase activity (R.I.=0.13±0.11; n=8; p<0.001). In contrast, Cdk1 in endos00003 and elgi1 immunoprecipitates had normal kinase activity (1.52±0.96, n=9, and 1.47±1.02, n=8, respectively; p>0.05 for both), although Cdk1 was present at slightly reduced levels and had altered electrophoretic mobility (appeared hypophosphorylated) in endos00003 mutants (Fig. 3E; see Fig. 2M in supplementary material). These in vitro results suggest that endos may not be required for normal Cdk1 activity in maturing oocytes; however, it is equally likely that in vitro phosphorylation of histone H1 may not reflect endogenous phosphorylation of key substrates in vivo (see Discussion).

MPM2 antibodies recognize conserved phosphoepitopes of mitotic proteins (Davis et al., 1983), and many of the MPM2 epitopes result from Cdk1 activation in vertebrates (Skoufias et al., 2007). In Drosophila, Polo kinase is required for the generation of MPM2 epitopes (Logarinho and Sunkel, 1998). In wild-type stage 14 oocytes, many MPM2-reactive proteins are present, while in cdc2E1–24/cdc2B47 mutants they are severely reduced, indicating that generation of MPM2 epitopes requires Cdk1 activity in Drosophila oocytes. twine1 and endos00003 stage 14 oocytes also had drastically reduced MPM2 levels, suggestive of low Polo and/or Cdk1 activity in vivo (Fig. 3F, see Fig. 2M in supplementary material).

Elgi, a predicted E3 ubiquitin ligase, interacts with Endos in vitro

To identify proteins that directly bind to Endos and better understand its role in the meiosis, we performed a Drosophila in vitro expression cloning binding screen (Fig. 4A) modified from the approach previously used to screen for kinase substrates (Lee et al., 2005). Sequence-verified cDNAs corresponding to 5,856 unique Drosophila genes were converted into 35S-labeled proteins, which were screened for binding to an Endos fusion protein. Of the two candidates that bound specifically to Endos, the predicted E3 ubiquitin ligase encoded by CG17033 (renamed early girl, or elgi; see below) was the strongest (Fig. 4B).

Elgi has a highly conserved RING finger domain and it has vertebrate homologs (Fig. 4C), including human Nrdp1 protein, which has E3 ubiquitin ligase activity in vitro (Qiu and Goldberg, 2002; Qiu et al., 2004). Remarkably, the closely related gene CG9014 encodes a protein identified as an Endos interactor in a large-scale yeast two-hybrid screen (Giot et al., 2003). Elgi and CG9014 are the most closely related Drosophila E3 ligases, sharing 44% identity and 63% similarity at the amino acid level. We confirmed that Endos binds to Elgi and CG9014 but not to more distantly related E3 ligases (Fig. 4B), but were unable to generate high quality anti-Elgi polyclonal antibodies to confirm the Endos-Elgi interaction in vivo. We detected elgi and CG9014 mRNA expression in heads and carcasses but elgi predominates in ovaries (see Fig. 7A in supplementary material).

elgi mutation results in premature metaphase I

To examine the role of elgi in meiotic maturation, we generated two deletion alleles (Fig. 4D). elgi1 is likely a null allele because no mRNA is detected in homozygotes (see Fig. 7B in supplementary material). Disruption of elgi results in semi-lethality, indicating a role during development. elgi2 lacks a small portion of the elgi coding region (Fig. 4D), and some mRNA is still detected in trans to elgi1 (see Fig. 7B in supplementary material). Although elgi1 females have normal ovarian morphology and are fertile, progression from prophase I to metaphase I occurs prematurely (Fig. 1Q–V, see Table 1 in supplementary material), prompting the name early girl, or elgi. Nuclear envelope breakdown is also premature in elgi1 mutants (see Fig. 3M–Q in supplementary material), with metaphase I spindles comparable to those of control oocytes (Fig. 2F) and perhaps slightly elevated MPM2 levels (Fig. 3F; clear increase in elgi1 MPM2 levels observed in two out of three experiments). elgi1/Df(3L)brm11 hemizygotes show similar phenotypes (see Table 1 in supplementary material), consistent with elgi1 being a null allele. When elgi1 is in trans to elgi2, an even higher percentage of oocytes undergoes premature metaphase I, suggesting a dominant negative effect. The premature metaphase I in elgi mutants in contrast to the failed metaphase I transition of endos00003 oocytes suggests that endos and elgi play antagonistic roles in meiotic maturation.

Different models could explain how Endos and Elgi interact. E3 ubiquitin ligases in combination with E1 ubiquitin activating and E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzymes covalently attach ubiquitins to target proteins, thereby inducing their degradation or modulating their subcellular localization, interaction with other proteins, or activity (Pickart, 2001). It is unlikely that Endos is a direct target of Elgi because we do not observe any changes in Endos mobility or levels in elgi1 oocytes (Fig. 4E). Endos may instead inhibit Elgi by blocking its interaction with target proteins. Because Polo kinase and Twine protein levels are reduced in endos00003 mutants, we asked whether this was due to high levels of Elgi activity. However, Twine and Polo levels are still reduced in endos00003 elgi1 double mutants and unaffected in elgi1 mutants (Fig. 3A–C, see Fig. 6 in supplementary material), suggesting that the Elgi is not responsible for degrading these proteins. In addition, the meiotic maturation defect of endos00003 elgi1 double mutants is very similar to that of endos00003 mutants (see Table 1 in supplementary material). This is likely not due to redundancy between elgi and CG9014 because loss of elgi function alone causes premature meiotic maturation (Fig. 1V). Instead, we propose that Endos controls meiotic maturation via parallel mechanisms by modulating the protein levels of Polo kinase (and Twine) and also Elgi activity (Fig. 4F).

The meiotic function of α-endosulfine may be evolutionarily conserved

Endos is 46% identical to mammalian α-endosulfines (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2004). To determine if α-endosulfine is also functionally conserved, we tested whether expression of ENSA, the human homolog, could rescue the endos00003 meiotic maturation defect (Fig. 5A–F). When UAS-endos transgenes were specifically expressed in the germline of endos00003 females, transition to metaphase I, stage 14 dehydration, and fertility were efficiently restored (Fig. 5C,F). Remarkably, germline-driven UAS-ENSA transgenes also significantly rescued the endos00003 defects (Fig. 5D,F), suggesting conservation of the molecular function of α-endosulfine.

We also asked if α-endosulfine is expressed in adult mammalian oocytes. We detected mRNA expression of α-endosulfine in mouse ovaries (J.R.V.S. and D.D.-B., unpublished). Our anti-Endos antibodies (generated against full-length Endos; see Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2004) recognize ENSA (see Fig. 5E), which is 93% identical to the mouse protein. We therefore used them for immunohistochemistry, detecting strong expression of α-endosulfine protein in the cytoplasm of adult mouse oocytes (Fig. 5G,H). These data suggest that the meiotic function of α-endosulfine may have been evolutionarily conserved.

DISCUSSION

Our studies demonstrate previously unknown roles for α-endosulfine in meiotic maturation. Endos is required to ensure normal Polo kinase levels and, perhaps indirectly, to stabilize Twine/Cdc25 phosphatase. A generalized effect of endos on protein translation or stability is unlikely, given that CyclinB and actin protein levels are both unaffected by loss of endos function. Due to problems in maintaining high levels of Twine or Polo transgenes in endos mutants, however, we could not demonstrate that the low levels of Twine and/or Polo indeed cause the endos meiotic maturation defects. In addition, our data suggest that Endos has a separate role during meiotic maturation via the negative regulation of Elgi. The function of α-endosulfine in meiotic maturation may potentially be conserved because ENSA, the human homolog, can efficiently rescue the endos mutant phenotype and because α-endosulfine is expressed in mammalian oocytes. It would be interesting and informative to determine whether elimination of α-endosulfine function in the mouse germline results in similar meiotic maturation defects and sterility.

Levels of Cdc25 phosphatases are tightly regulated during the cell cycle by the balance of protein synthesis and degradation (Boutros et al., 2006; Busino et al., 2004; Karlsson-Rosenthal and Millar, 2006). Phosphorylation of Ser18 and Ser116 residues by CyclinB/Cdk1 results in mouse Cdc25A stabilization, thereby creating a positive feedback loop that allows Cdc25A to dephosphorylate and activate CyclinB/Cdk1. Evidence from Xenopus studies indicates that phosphorylation and activation of Cdc25 by Polo-like kinase generate MPM2 epitopes, which reflect high CyclinB/Cdk1 activity (Kumagai and Dunphy, 1996; Qian et al., 2001). Moreover, a recent study in C. elegans demonstrates a role for Polo-like kinase in meiotic maturation (Chase et al., 2000). It is therefore likely that the low Twine levels observed in endos mutants are an indirect consequence of reduced Polo levels, which may result in impaired Cdk1 activity. It remains a formal possibility, however, that endos regulates Twine and Polo levels independently of each other. In either case, there are clear differences between the endos and twine phenotypes: only endos mutant oocytes show severe reduction in Polo and slight reduction in Cdk1 levels; twine but not endos mutants show slightly elevated CyclinB levels; the phosphorylation status of Cdk1 seems differently altered in endos (appears hypophosphorylated) and twine (appears hyperphosphorylated, as expected) relative to control oocytes; and in vitro Cdk1 activity is reduced in immunoprecipitates from twine but not endos oocytes.

It is possible that the wild-type levels of in vitro phosphorylation of histone H1 of endos00003 immunoprecipitates accurately reflect Cdk1 kinase activity levels in living endos00003 oocytes, in which case we would conclude that the reduction in Twine and Polo levels observed in endos00003 mutants is not sufficient to affect Cdk1 activity, and that the MPM2 epitope level reduction is simply due to low Polo levels. Another possibility is that in vitro phosphorylation of histone H1 is not reflective of the in vivo Cdk1 kinase activity levels in endos mutants. For example, Cdk1 substrate specificity may be altered in endos mutants such that endogenous substrates other than histone H1 are not properly phosphorylated, or Cdk1 kinase activity may be reduced in specific subcellular pools in these mutant oocytes, perhaps via local alterations in phosphorylation or CyclinB levels. In fact, spatial regulation of CyclinB has been reported during meiosis and syncytial mitotic cycles in Drosophila (Huang and Raff, 1999; Swan and Schupbach, 2007).

Although we were unable to confirm the Endos-Elgi interaction in vivo, their strong interaction in vitro combined with the premature meiotic maturation phenotype of elgi mutants suggest that these genes function in the same pathway. The mammalian Elgi homologue, Nrdp1, has been shown to act as an E3 ubiquitin ligase in vitro to promote degradation of the ErbB3 and ErbB4 receptor tyrosine kinases (Qiu and Goldberg, 2002) and of the inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein BRUCE (Qiu et al., 2004). It would be interesting to determine whether Elgi also has E3 ligase activity in flies and to identify its direct targets. Nrdp1 mRNA is expressed in multiple human tissues including the ovary (Qiu and Goldberg, 2002); however, a role for Nrdp1 in meiotic maturation or modulation of Cdk1 has not been examined. The strong degree of amino acid similarity between human Nrdp1 and Elgi suggests functional conservation.

The premature entry into metaphase I observed in elgi null mutants in the absence of effects on Polo or Twine levels suggests that Endos uses a separate mechanism that involves elgi function to control the timing of Cdk1 activation and ultimately that of meiotic maturation, without necessarily affecting the final levels of Cdk1 activation. The premature meiotic maturation phenotype of elgi mutants is reminiscent of the phenotype recently reported for matrimony heterozygous mutants (Xiang et al., 2007). In these studies, Matrimony was reported to interact with Polo kinase in vivo and function as a Polo inhibitor, with a suggested role in finely controlling the timing of meiotic maturation. One possible model to explain the premature meiotic maturation of elgi mutant oocytes is that Elgi positively regulates the interaction between Matrimony and Polo; Endos may control the precise timing of meiotic maturation by inhibiting this E3 in addition to having a key role in promoting high Polo (and Twine) protein levels. It will be very interesting to experimentally address this possibility in future studies.

In addition to having key roles in meiosis, we also found that Drosophila α-endosulfine is required during early embryonic mitoses. These findings are consistent with recent studies showing, as part of a large-scale screen for genes required for mitotic spindle assembly in Drosophila S2 cells, that disruption of α-endosulfine expression by RNA interference produces defects such as chromosome misalignment and abnormal spindles (Goshima et al., 2007). It is conceivable that α-endosulfine uses similar mechanisms in both meiosis and mitosis. Further characterization of the role of α-endosulfine in mitosis will help address this question.

Given the central role that we report for Endos in meiotic maturation and the fact that Endos is expressed throughout oogenesis, it will next be essential to investigate how Endos activity is regulated as the oocyte develops and becomes competent to undergo meiotic maturation. Intriguingly, Endos contains a highly conserved protein kinase A (PKA) phosphorylation site. Indeed, mammalian homologs can be phosphorylated by PKA at this site (Dulubova et al., 2001) and in vertebrate oocytes, high levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and PKA activity inhibit the resumption of meiosis by inhibiting CyclinB/Cdk1 activity (Burton and McKnight, 2007; Kovo et al., 2006). Upon oocyte meiotic maturation, cAMP levels and PKA activity decrease (Burton and McKnight, 2007; Kovo et al., 2006). Although the evidence suggests that PKA-dependent phosphorylation is responsible for activation of the Cdk1-inhibitory kinase Wee1 and inactivation of the Cdk1-activating phosphatase Cdc25 (Burton and McKnight, 2007), it is possible that PKA has additional roles in controlling meiotic maturation, perhaps via α-endosulfine. In fact, two forms of Endos with different electrophoretic mobilities are present in Drosophila ovaries (Drummond-Barbosa and Spradling, 2004), with the lower mobility form specifically present in stage 14 oocytes (J.R.V.S. and D.D.-B., unpublished). However, it remains to be determined whether these different forms of Endos are due to phosphorylation and, if so, what the effect of phosphorylation is on Endos activity.

Finally, although this was not the focus of these studies, some of our results suggest that Endos does not regulate insulin secretion (see Fig. 1 in supplementary material), differing from mammalian studies that link α-endosulfine to this process (Virsolvy-Vergine et al., 1988; Virsolvy-Vergine et al., 1992). It is possible that this discrepancy is due to differences in the function of α-endosulfine between species, perhaps reflecting an evolutionarily newer role of α-endosulfine in the control of insulin secretion. It is important, however, to emphasize that the role of α-endosulfine in insulin secretion has not been tested in vivo. Nevertheless, human α-endosulfine mRNA is expressed in multiples tissues including heart, brain, lung, pancreas, kidney, liver, spleen, and skeletal muscle (Heron et al., 1998), and we show herein that it is also expressed in the ovary. The wide range of expression of human α-endosulfine suggests that it is likely to play multiple biological roles perhaps including, as our studies point to, a potential role in meiotic maturation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

J.R.V.S. and D.D.-B. designed and interpreted experiments, and wrote manuscript. J.R.V.S. performed all Drosophila experiments, including DIVEC screen. J.R.V.S., B.C. performed live imaging. S.T. conducted mouse ovary immunohistochemistry and provided mouse cDNAs, with support from S.K.D. L.A.L. conceived of and established the DIVEC methodology for binding screens, and provided radiolabeled protein pools for primary screen. We are grateful to E. Lee for expert advice on the DIVEC screen, and for the pCS2 vector, and to T. Murphy for pUASpI. We thank M. Fuller, R. S. Hawley, and the Bloomington Stock Center for Drosophila stocks, and C. Sunkel, J. Großhans and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies. We thank L. Zhang, K. LaFever, and T. Daikoku for technical assistance, and L. LaFever for making the UAS-endos lines. Thanks to D. Miller and members of his lab for help with Nomarski microscopy, and to C. Spencer and S. Von Stetina for help with movie assembly. We are grateful to H.– J. Hsu, E.T. Ables, L. LaFever, and anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM069875 (D.D.-B.), GM074044 (L.A.L.) and HD12304 (S.D.), and training grants 2T32HD007502 (support for J.R.VS) and 2T32HD007043 (support for J.R.VS and S.T.).

REFERENCES

- Alphey L, Jimenez J, White-Cooper H, Dawson I, Nurse P, Glover DM. twine, a cdc25 homolog that functions in the male and female germline of Drosophila. Cell. 1992;69:977–988. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90616-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bataille D, Heron L, Virsolvy A, Peyrollier K, LeCam A, Gros L, Blache P. alpha-Endosulfine, a new entity in the control of insulin secretion. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1999;56:78–84. doi: 10.1007/s000180050008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutros R, Dozier C, Ducommun B. The when and wheres of CDC25 phosphatases. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2006;18:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JS, Lockwood WK, Li L, Cohen SM, Edgar BA. Drosophila's insulin/PI3-kinase pathway coordinates cellular metabolism with nutritional conditions. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton KA, McKnight GS. PKA, germ cells, and fertility. Physiol. 2007;22:40–46. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00034.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busino L, Chiesa M, Draetta GF, Donzelli M. Cdc25A phosphatase: combinatorial phosphorylation, ubiquitylation and proteolysis. Oncogene. 2004;23:2050–2056. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase D, Serafinas C, Ashcroft N, Kosinski M, Longo D, Ferris DK, Golden A. The polo-like kinase PLK-1 is required for nuclear envelope breakdown and the completion of meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genesis. 2000;26:26–41. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200001)26:1<26::aid-gene6>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtot C, Fankhauser C, Simanis V, Lehner CF. The Drosophila cdc25 homolog twine is required for meiosis. Development. 1992;116:405–416. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis FM, Tsao TY, Fowler SK, Rao PN. Monoclonal antibodies to mitotic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:2926–2930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.10.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond-Barbosa D, Spradling AC. Alpha-endosulfine, a potential regulator of insulin secretion, is required for adult tissue growth control in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 2004;266:310–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulubova I, Horiuchi A, Snyder GL, Girault JA, Czernik AJ, Shao L, Ramabhadran R, Greengard P, Nairn AC. ARPP-16/ARPP-19: a highly conserved family of cAMP-regulated phosphoproteins. J. Neurochem. 2001;77:229–238. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.t01-1-00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar BA, O'Farrell PH. The three postblastoderm cell cycles of Drosophila embryogenesis are regulated in G2 by string. Cell. 1990;62:469–480. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawlinski P, Nikolay R, Goursot C, Lawo S, Chaurasia B, Herz HM, Kussler-Schneider Y, Ruppert T, Mayer M, Grosshans J. The Drosophila mitotic inhibitor Fruhstart specifically binds to the hydrophobic patch of cyclins. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:490–496. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giot L, Bader JS, Brouwer C, Chaudhuri A, Kuang B, Li Y, Hao YL, Ooi CE, Godwin B, Vitols E, et al. A protein interaction map of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2003;302:1727–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.1090289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshima G, Wollman R, Goodwin SS, Zhang N, Scholey JM, Vale RD, Stuurman N. Genes required for mitotic spindle assembly in Drosophila S2 cells. Science. 2007;316:417–421. doi: 10.1126/science.1141314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron L, Virsolvy A, Peyrollier K, Gribble FM, Le Cam A, Ashcroft FM, Bataille D. Human alpha-endosulfine, a possible regulator of sulfonylureasensitive KATP channel: molecular cloning, expression and biological properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:8387–8391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong A, Lee-Kong S, Iida T, Sugimura I, Lilly MA. The p27cip/kip ortholog dacapo maintains the Drosophila oocyte in prophase of meiosis I. Development. 2003;130:1235–1242. doi: 10.1242/dev.00352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Raff JW. The disappearance of cyclin B at the end of mitosis is regulated spatially in Drosophila cells. Embo J. 1999;18:2184–2195. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson-Rosenthal C, Millar JB. Cdc25: mechanisms of checkpoint inhibition and recovery. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:285–292. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashevsky H, Wallace JA, Reed BH, Lai C, Hayashi-Hagihara A, Orr-Weaver TL. The anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome is required during development for modified cell cycles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11217–11222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172391099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RC. The meiotic behavior of the Drosophila oocyte. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1970;28:125–168. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto T. Cell-cycle control during meiotic maturation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:654–663. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovo M, Kandli-Cohen M, Ben-Haim M, Galiani D, Carr DW, Dekel N. An active protein kinase A (PKA) is involved in meiotic arrest of rat growing oocytes. Reproduction. 2006;132:33–43. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai A, Dunphy WG. Purification and molecular cloning of Plx1, a Cdc25-regulatory kinase from Xenopus egg extracts. Science. 1996;273:1377–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LA, Lee E, Anderson MA, Vardy L, Tahinci E, Ali SM, Kashevsky H, Benasutti M, Kirschner MW, Orr-Weaver TL. Drosophila genome-scale screen for PAN GU kinase substrates identifies Mat89Bb as a cell cycle regulator. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logarinho E, Sunkel CE. The Drosophila POLO kinase localises to multiple compartments of the mitotic apparatus and is required for the phosphorylation of MPM2 reactive epitopes. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:2897–2909. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.19.2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahowald AP, Goralski TJ, Caulton JH. In vitro activation of Drosophila eggs. Dev. Biol. 1983;98:437–445. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90373-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailand N, Podtelejnikov AV, Groth A, Mann M, Bartek J, Lukas J. Regulation of G(2)/M events by Cdc25A through phosphorylation-dependent modulation of its stability. Embo J. 2002;21:5911–5920. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maines JZ, Wasserman SA. Post-transcriptional regulation of the meiotic Cdc25 protein Twine by the Dazl orthologue Boule. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:171–174. doi: 10.1038/11091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis J, Spradling A. Identification and behavior of epithelial stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 1995;121:3797–3807. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson I, Hoffmann I. Cell cycle regulation by the Cdc25 phosphatase family. Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 2000;4:107–114. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4253-7_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page AW, Orr-Weaver TL. Stopping and starting the meiotic cell cycle. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1997;7:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickart CM. Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian YW, Erikson E, Taieb FE, Maller JL. The polo-like kinase Plx1 is required for activation of the phosphatase Cdc25C and cyclin B-Cdc2 in Xenopus oocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:1791–1799. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu XB, Goldberg AL. Nrdp1/FLRF is a ubiquitin ligase promoting ubiquitination and degradation of the epidermal growth factor receptor family member, ErbB3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14843–14848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232580999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu XB, Markant SL, Yuan J, Goldberg AL. Nrdp1-mediated degradation of the gigantic IAP, BRUCE, is a novel pathway for triggering apoptosis. Embo J. 2004;23:800–810. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed BH, Orr-Weaver TL. The Drosophila gene morula inhibits mitotic functions in the endo cell cycle and the mitotic cell cycle. Development. 1997;124:3543–3553. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagata N. Meiotic metaphase arrest in animal oocytes: its mechanisms and biological significance. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:22–28. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)81034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santel A, Blumer N, Kampfer M, Renkawitz-Pohl R. Flagellar mitochondrial association of the male-specific Don Juan protein in Drosophila spermatozoa. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:3299–3309. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.22.3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santel A, Winhauer T, Blumer N, Renkawitz-Pohl R. The Drosophila don juan (dj) gene encodes a novel sperm specific protein component characterized by an unusual domain of a repetitive amino acid motif. Mech. Dev. 1997;64:19–30. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoufias DA, Indorato RL, Lacroix F, Panopoulos A, Margolis RL. Mitosis persists in the absence of Cdk1 activity when proteolysis or protein phosphatase activity is suppressed. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:671–685. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling A. The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. Developmental Genetics of Oogenesis. [Google Scholar]

- Spradling AC, Rubin GM. Transposition of cloned P elements into Drosophila germ line chromosomes. Science. 1982;218:341–347. doi: 10.1126/science.6289435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern B, Ried G, Clegg NJ, Grigliatti TA, Lehner CF. Genetic analysis of the Drosophila cdc2 homolog. Development. 1993;117:219–232. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimura I, Lilly MA. Bruno inhibits the expression of mitotic cyclins during the prophase I meiotic arrest of Drosophila oocytes. Dev. Cell. 2006;10:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan A, Schupbach T. The Cdc20 (Fzy)/Cdh1-related protein, Cort, cooperates with Fzy in cyclin destruction and anaphase progression in meiosis I and II in Drosophila. Development. 2007;134:891–899. doi: 10.1242/dev.02784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Paria BC, Dey SK, Das SK. Differential uterine expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors correlates with uterine preparation for implantation and decidualization in the mouse. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5310–5321. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theurkauf WE, Hawley RS. Meiotic spindle assembly in Drosophila females: behavior of nonexchange chromosomes and the effects of mutations in the nod kinesin-like protein. J. Cell Biol. 1992;116:1167–1180. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.5.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doren M, Williamson AL, Lehmann R. Regulation of zygotic gene expression in Drosophila primordial germ cells. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:243–246. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virsolvy-Vergine A, Bruck M, Dufour M, Cauvin A, Lupo B, Bataille D. An endogenous ligand for the central sulfonylurea receptor. FEBS Lett. 1988;242:65–69. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80986-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virsolvy-Vergine A, Leray H, Kuroki S, Lupo B, Dufour M, Bataille D. Endosulfine, an endogenous peptidic ligand for the sulfonylurea receptor: purification and partial characterization from ovine brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:6629–6633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodermaier HC. APC/C and SCF: controlling each other and the cell cycle. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R787–R796. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Lin H. The division of Drosophila germline stem cells and their precursors requires a specific cyclin. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker M. Control of meiotic arrest. Rev. Reprod. 1996;1:127–135. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0010127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White-Cooper H, Alphey L, Glover DM. The cdc25 homologue twine is required for only some aspects of the entry into meiosis in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 1993;106:1035–1044. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.4.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White-Cooper H, Schafer MA, Alphey LS, Fuller MT. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional control mechanisms coordinate the onset of spermatid differentiation with meiosis I in Drosophila. Development. 1998;125:125–134. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Takeo S, Florens L, Hughes SE, Huo LJ, Gilliland WD, Swanson SK, Teeter K, Schwartz JW, Washburn MP, et al. The inhibition of polo kinase by matrimony maintains G2 arrest in the meiotic cell cycle. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.