Abstract

Production of clinical-grade gene therapy vectors for human trials remains a major hurdle in advancing cures for a number of otherwise incurable diseases. We describe a system based on a stably transformed insect cell lines harboring helper genes required for vector production. Integrated genes remain silent until the cell is infected with a single baculovirus expression vector (BEV). The induction of expression results from a combination of the amplification of integrated resident genes (up to 1,200 copies per cell) and the enhancement of the expression mediated by the immediate-early trans-regulator 1 (IE-1) encoded by BEV. The integration cassette incorporates an IE-1 binding target sequence from wild-type Autographa californica multiple nuclear polyhedrosis virus, a homologous region 2 (hr2). A feed-forward loop is initiated by one of the induced proteins, Rep78, boosting the amplification of the integrated genes. The system was tested for the coordinated expression of 7 proteins required to package recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV)2 and rAAV1. The described arrangement provided high levels of Rep and Cap proteins, thus improving rAAV yield by 10-fold as compared with the previously described baculovirus/rAAV production system.

Keywords: baculovirus, gene therapy

High production costs of clinical-grade gene therapy vectors remain a major impediment preventing many research laboratories from entering the field. This is especially true for replication-deficient recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors, which are produced for the most part by plasmid DNA cotransfection. Only recently, alternative scale-up production protocols such as those using baculovirus expression vectors (BEVs) have been developed. Traditionally, BEVs have emerged as one of the most versatile systems for protein production. They provide a high yield combined with the posttranslational modifications of proteins. In addition to basic protein production, BEVs have been used for more complicated tasks such as the synthesis of heterologous multiprotein complexes (1), production of a variety of virus-like particles, and the assembly of gene therapy vehicles such as rAAV vectors (2). The latter strategy uses insect cells coinfected with 3 BEVs, a procedure potentially capable of manufacturing rAAV in “exa-scale” format (3). Although extremely promising, the original protocol has not been widely adopted due to several shortcomings, including a requirement for the coinfection with 3 different helpers: Bac-Rep, Bac-VP, and Bac-GOI (gene of interest flanked by AAV inverted terminal repeats). Only recently, Chen (4) has reported a significantly improved system in which rep and cap helper genes in the respective BEVs incorporated artificial introns.

In the following study, a simple and efficient system of rAAV production in insect cells is described. The system takes advantage of DNA regulatory elements from 2 unrelated viruses: Autographa californica multiple nuclear polyhedrosis virus (AcMNPV) and AAV2. The endpoint design consists of only 2 components: (i) a stable Sf9-based cell line incorporating integrated copies of rep and cap genes, and (ii) Bac-GOI. rep and cap genes are designed to remain silent until the cell is infected with Bac-GOI helper, which provides both rAAV transgene cassette and immediate-early (IE-1) transcriptional trans-regulator. Infection with Bac-GOI initiates the rescue/amplification of the integrated AAV helper genes, resulting in dramatic induction of the expression and assembly of rAAV. The arrangement provides high levels of Rep and Cap proteins in every cell, thus improving rAAV yields by 10-fold. The described vectors are modular in design and could be used for the production of other multiprotein complexes.

Results

Cloning of AcMNPV Homologous Region 2 (hr2).

To simplify the system and reduce the number of components, we sought to derive Sf9-based stable lines expressing AAV rep and cap genes. The challenge of expressing AAV helper genes in the heterologous environment of an insect cell necessitates the use of baculovirus-derived promoters (e.g., polh), which are fully functional only in the context of the whole genome (i.e., next to other viral regulatory elements). Simple cassettes with rep and cap ORFs placed downstream of baculovirus promoters and integrated into the host chromosome will not achieve expression levels similar to those of the same modules in the context of a BEV. Therefore, we set forth to develop a modular cassette capable of the highest levels of expression when remotely separated from the BEV. An additional challenge in constructing such cassettes is that in the WT AAV genome, genes encoded by colinear ORFs within one DNA sequence are transcribed into separate mRNAs from the P5, P19, and P40 promoters. Making 3 independent integrating modules, each driven by its own promoter, makes the selection process technically complicated.

We have previously documented that BEV Bac-Rep78 produced small amounts of Rep52 derived from mRNA transcribed from AAV2 P19 promoter, suggesting that the WT AAV P19 sequence retains some residual promoter activity in insect cells (5). Accordingly, we hypothesized that the rep78 ORF could be designed to express both Rep78 and Rep52, hence eliminating the need for a separate vector encoding Rep52 ORF. We further inferred that a BEV-derived enhancer, such as hr sequence, could be used to increase the transcription rate from WT AAV P19 promoter, thus improving the stoichiometry of Rep52/78.

To test our hypothesis, we have cloned hr2 from the WT AcMNPV and compared its sequence to the other 2 previously published hr2 sequences (6, 7) (Fig. S1). Our hr2 isolate (hereafter referred to as hr2-0.9), although homologous to both reported sequences, showed significant variability, including multiple single-nucleotide deletions and insertions, as well as longer stretches such as a 72-bp insertion incorporating an additional 28-bp IE-1 binding element.

Rep-Expressing Cassettes.

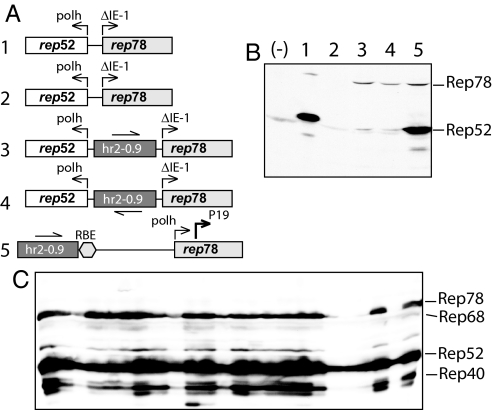

To test whether hr2-0.9 could enhance the transcription from WT AAV2 P19 promoter, we constructed a series of plasmid vectors (Fig. 1A) and tested the expression of rep52 and rep78 genes in a transient transfection assay in insect Sf9 cells. As reported earlier (2), infection of Sf9 cells with Bac-Rep harboring head-to-head rep78 and rep52 genes resulted in the expression of both Rep52 and Rep78 proteins (Fig. 1B, lane 1). The same cassette in the context of transfer plasmid pFBD-LSR (2) did not produce any Rep proteins (Fig. 2B, lane 2), suggesting a requirement for an enhancer apparently present in a context of Bac-Rep BEV vector carrying Rep-expression cassettes. Insertion of hr2-0.9 between head-to-head polh and ΔIE-1 promoters created a cassette reminiscent of a transcription control element described earlier (8), with the exception of a hr2-0.9 substituted for hr5. As expected, in the presence of BEV-derived IE-1 trans-regulator (supplied by helper Bac-VP BEV), the enhancer mediated expression of both Rep78 and Rep52, the latter one expressed at a lower rate despite the fact that it was driven by a considerably stronger polh promoter (Fig. 2B, lane 3). The orientation of hr2-0.9 did not appear to significantly change the expression of either gene (Fig. 2B, lane 4). Because of a limited success in expressing Rep52, we redesigned the vector placing rep78 ORF under control of the late polh promoter while completely removing the polh/rep52 cassette. We also moved hr2-0.9 further upstream to emulate the context of BEV genome with more distantly positioned hr elements.

Fig. 1.

Expression of rep52/78-encoding cassettes. (A) Schematic representation of lane 1, Rep-expression cassettes in recombinant BEV Bac-Rep from Urabe et al. (2); lane 2, transfer plasmid used to derive Bac-Rep; lanes 3–5, plasmid constructs derived for the current project; polh, late polyhedrin promoter; ΔIE-1, attenuated OpMNPV immediate early promoter (33); P19, WT AAV2 P19 promoter; RBE, Rep-binding element (WT AAV2 nucleotides 87–126); leftmost numbers correspond to lanes in B. (B) Western blotting analysis of Rep52/78 proteins in Sf9 cells after transient transfection with various plasmid DNAs. Cells in the lane marked (-) are mock-transfected; lane 1, infected with Bac-Rep (multiplicity of infection, moi, of 5); cells in lanes 2–5 are transfected with the respective plasmids shown in A and infected with Bac-VP (2) (moi of 5) to supply trans-regulator IE-1. (C) Western blotting analysis of Rep proteins extracted from individual stable BSR cell lines after infection with Bac-VP (moi of 5) and harvested 72 hr postinfection.

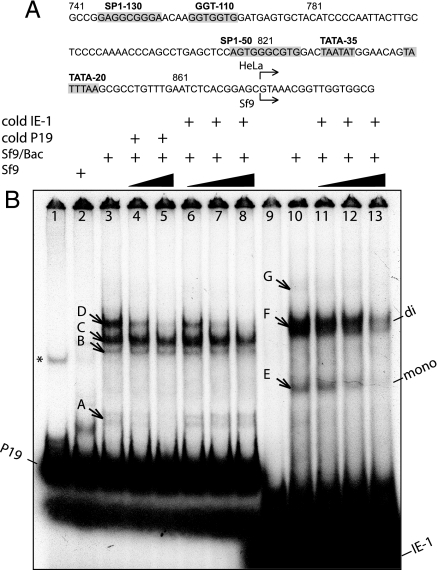

Fig. 2.

Analysis of AAV2 P19 promoter activation in Sf9 cells. (A) AAV2 P19 promoter nucleotides are indicated above the sequence. Shaded boxes outline sequences with homology to SP1, GGT, and TATA transcription factor binding elements (9, 25). The P19 transcription initiation sites in mammalian (HeLa) and insect cells (Sf9) are indicated by bent arrows. (B) EMSA assay. 5′-End-labeled 128-bp PCR fragment of P19 promoter (AAV2 nucleotides 704–831, lanes 1–8) and 5′-end-labeled IE-1 consensus-binding element (34) (lanes 9–13) are incubated with crude nuclear extract derived from Sf9 infected with BEV. Samples in the control lanes 1 and 9 contain no nuclear extracts, whereas in lane 2 the probe is incubated with cell extract from uninfected Sf9. In lanes 4 and 5 [32P]P19 DNA probe is challenged with unlabeled P19 promoter probe (5- and 15-fold excess, respectively); in lanes 6, 7, and 9, with unlabeled IE-1 probe (5-, 25-, and 100-fold excess); in lanes 11, 12, and 13, with unlabeled IE-1 probe (5-, 25-, and 100-fold excess). Different DNA–protein complexes are marked by arrows and labeled with letters. Nonspecific DNA band, a by-product of PCR in lane 1, is marked with *. The presumed IE-1 monomer and dimer/DNA–protein complexes are marked at the right edge of the gel.

To introduce an additional regulatory element upstream of the rep78 ORF, we have inserted the DNA sequence containing the WT AAV2 Rep-binding element (RBE). It was shown earlier that either AAV ITR or P5 RBE modulates the expression from the P19 promoter (9). In addition, P5 RBE mediated the amplification of integrated AAV sequences in mammalian cells (10), thus dramatically improving yields of rAAV production in HeLa-based packaging cell lines. The combination of introduced changes resulted in a dramatic up-regulation of the expression of the rep52 gene driven by the AAV2 P19 promoter (Fig. 2B, lane 5). Therefore, combining regulatory elements from both the AAV and BEV in 1 vector allowed us to achieve an efficient expression of both Rep78 and Rep52 from a single rep78 ORF cassette.

Rep-Expressing Stable Cell Lines.

For the purpose of rAAV production, stable mammalian cell lines expressing AAV Rep78/52 are notoriously difficult to generate due to the genotoxic effect of the rep component (11). To make a stable line, a complete shutoff of the integrated rep ORF is therefore required. Until now, no similar stable insect cell-based lines expressing AAV rep/cap functions have been reported. Having designed the vector with hr2-0.9-mediated robust expression of both Rep78 and Rep52 in Sf9 cells, we next asked whether the Rep-expression cassette could be used to derive stable cell lines.

The plasmid pIR-rep78-hr2-RBE (no. 5 in Fig. 1A), in addition to the Rep expression cassette, was constructed to harbor the OpIE1 viral promoter-driven bsd (blasticidin S deaminase) gene conferring resistance to blasticidin S (BS). This plasmid had been used to transfect Sf9 cells and select for BS resistance to derive 24 individual stable cell lines. Remarkably, all analyzed BS-resistant (BSR) cell lines, upon infection with Bac-VP BEV, showed expression of both Rep proteins albeit at different levels and at variable ratios (Fig. 1C).

Analysis of AAV2 P19 Promoter in Sf 9 Cells.

Induced expression of rep52 suggested 2 possibilities: (i) a read-through activation from the upstream polh promoter similar to adenovirus type 5 early region 1 transcription (12), and (ii) activation by elements present within the P19 promoter itself. To distinguish between these 2 mechanisms, we mapped the transcription initiation site of the integrated rep gene from the rep/cap stable BSR line F3. Using RLM-RACE protocol, we determined that the transcription of the rep52 gene was initiated at AAV2 nucleotide 874 (Fig. 2A) (i.e., exactly at the same position as in mammalian cells). Therefore, it appeared that the upstream hr2-0.9 directed host cell- and BEV-encoded factors to initiate strong transcription from the heterologous P19 promoter.

We further hypothesized that BEV-encoded immediate early trans-activator IE-1 mediates the induction of P19 transcription by interacting with other transcription factors (TF) upstream of P19. To elucidate the mechanism, we performed an EMSA using a 128-bp P19 PCR fragment, which excluded both TATA-35 and TATA-20 sites. Little if any binding was detected in extracts from uninfected Sf9 cells (Fig. 2B, lane 2). On the contrary, extracts from BEV-infected Sf9 cells formed multiple DNA–protein complexes with the P19 promoter (Fig. 2B, lane 3). Some of these complexes (for example, doublet band marked “A”) were not associated with IE-1, as demonstrated by competitive binding to the unlabeled P19 probe (lanes 4 and 5) as opposed to the absence of such competition by the IE-1 consensus-binding element (lanes 6–8). The other complexes, such as band D, were clearly IE-1-specific as they were outcompeted by both P19 and IE-1 probes. Complexes B and C were partially competed with by 100-fold excess of IE-1 (lane 8), whereas 15-fold excess of p19 in lane 5 might not have been sufficient to significantly reduce the intensity of these bands.

Lanes 9–13 demonstrate the specificity of IE-1 consensus element in binding: 3 DNA-protein complexes (E, F, and G) are specifically competed with by unlabeled IE-1. Two lower bands presumably consist of monomer and dimer forms of IE-1 (13), whereas the upper complex, G, might represent an IE-1 dimer bound to another TF. Therefore, the Rep-expressing integrating cassette provides multiple TF-binding sites, thus emulating the regulation of the transcription in WT AAV2 genome expressing Rep78/52 and Rep68/40 from a single rep78 ORF.

Cap-Expressing Cassettes.

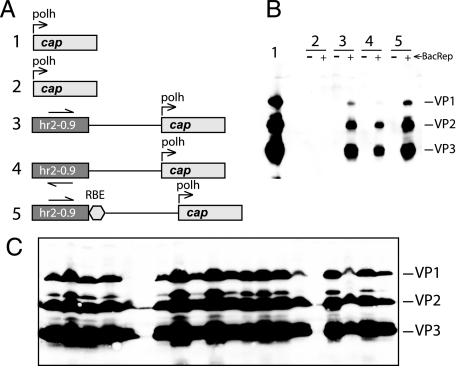

Using the same plasmid backbone and same regulatory elements, we have constructed a series of vectors to express AAV2 cap gene encoding structural proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3 (Fig. 3A). Similar to the rep cassette, the presence of the hr enhancer element was required for the cap gene to be expressed: the same polh-driven cap ORF was either strongly expressed in the context of BEV Bac-VP (2) (Fig. 3B, lane 1) or was completely silent in the plasmid backbone, regardless of whether IE-1 is supplied in trans by BEV (Fig. 3B, lanes 2+/−). Adding the hr2-0.9 element upstream resulted in the induction of viral protein expression but only in the presence of the BEV infection (Fig. 3 A and B, lanes 3+/−). The requirement for IE-1 appears to be absolute because we were unable to detect the expression of viral proteins in either of the constructs if transiently transfected cells were not infected with the Bac-Rep helper (Fig. 3B, all lanes marked by “-” symbol). We have also observed a slight orientational effect of hr2-0.9 (compare lanes 3+ and 4+ in Fig. 3B). In the presence of RBE, the viral protein expression appears to be also enhanced (lanes 3+ vs. 5+).

Fig. 3.

Expression of AAV2 cap-encoding cassettes. (A) Schematic representation of lane 1, cap expression cassette in BacVP as described by Urabe et al. (2); lane 2, same cassette in a shuttle plasmid backbone; lanes 3–5, plasmid constructs derived for the current project. Genetic element designations are the same as in the legend of Fig. 2. The leftmost numbers correspond to lanes in B. (B) Western blotting analysis of VP proteins in Sf9 cells after transient transfection with various plasmid DNAs. Cells in lane 1 are infected with BacVP (moi of 5), cells in lanes 2–5 are transfected with the respective plasmids (Fig. 3A) and either infected (+) or not infected (−) with Bac-Rep (2) (moi of 5) to supply trans-regulator IE-1 and Rep78. (C) Western blotting analysis of VP proteins extracted from individual stable BSR cell lines after infection with Bac-Rep (moi of 5) and harvested 72 hr postinfection.

We used pIR-VPm11-hr2-RBS (vector no. 5 in Fig. 3A) to derive 20 BSR stable cell lines that were selected and propagated similar to Rep-expressing lines. Upon induction of the cap gene with BacRep BEV infection, the majority (18 of 20) of the lines expressed VP1, VP2, and VP3 structural proteins of AAV2 (Fig. 3C).

rep/cap-Packaging Stable Cell Lines.

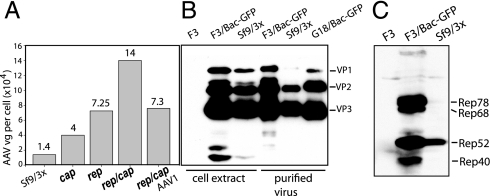

To derive Rep/VP-expressing lines, cells were cotransfected with the respective Rep- and Cap-expressing plasmids and BSR clones were derived. Twenty individual rep/cap-packaging cell lines were screened for their capacity to produce rAAV-GFP upon infection with the Bac-rAAV-GFP helper. One (designated F3) was selected for further analysis and for the production of rAAV. The yields of the purified vectors derived by using F3 packaging cells were on average 1.4 × 105 DNAse I-resistant particles (drp) per cell. This yield exceeded the yield of a triple infection protocol by 10-fold (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of rep/cap-packaging cell lines F3 and G18. (A) Average yields of purified rAAV-GFP tabulated in vector genomes per cell. Typical run is conducted in a 100-mL suspension culture; cells are infected with BEVs at an moi of 3: for Sf9 cells, with 3 BEV helpers (2); for cap stable cell line, with Bac-Rep and Bac-rAAV-GFP; for rep stable line, with Bac-VP and Bac-rAAV-GFP; for AAV2 (F3) and AAV1 (G18) rep/cap-packaging line, with Bac-rAAV-GFP. rAAV-GFP was purified as described earlier (35). Four runs per cell line had been conducted. (B) Western blotting analysis of AAV2 and AAV1 VP capsid proteins in crude lysates and purified rAAV-GFP. VP protein content in uninfected packaging line F3 (lane F3), F3 infected with Bac-rAAV-GFP (next lane) are compared to Sf9 cells infected with 3 BEV helpers (Sf9/3x). Crude lysates and purified rAAV-GFP are analyzed. (C) Western blotting analysis of Rep proteins in crude lysates in F3, F3 infected with Bac-rAAV-GFP, and Sf9 cells infected with 3 BEVs.

Because the described vectors are modular in design, the same control elements could be used for the expression of other AAV serotype capsid proteins. In particular, we have also constructed an AAV2 rep-AAV1 cap stable cell line dubbed G18. The analysis of the purified GFP-expressing AAV1 vector capsid composition and the yield is shown in Fig. 4B and 4A, respectively.

To characterize the mechanism of the higher yields we analyzed the amount of Rep and VP proteins synthesized in the F3 cell line. There was no detectable expression of VP (Fig. 4B, lane F3) or Rep (Fig. 4C, lane F3) proteins in uninfected F3 cells followed by the dramatic increase of the expression of both genes induced by Bac-GFP infection. At the time of harvest, the concentration of Cap proteins in F3 was 2 to 3 times higher than in triple-infected Sf9 cells (Fig. 4B, lane F3/Bac-GFP vs. Sf9/3x), whereas the amounts of Rep proteins, especially Rep78, were overwhelmingly higher compared with Sf9 cells coinfected with 3 BEV helpers (Fig. 4C).

Integrated rep and cap Genes Are Amplified by BEV Infection.

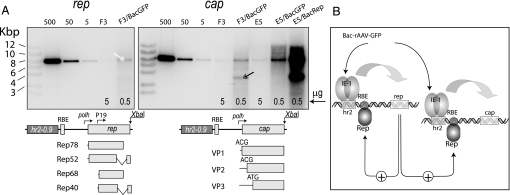

The mechanism of the induction of the expression of the integrated helper genes was investigated by analyzing total DNA isolated from stable F3 (rep/cap) and E5 (cap) cell lines (Fig. 5). Southern blotting in conjunction with RT-PCR assays was used to estimate the number of integrated copies. In uninfected cells from rep/cap line F3, 2 copies of rep and 4 copies of cap genes were documented (Table 1, Fig. 5, lanes marked F3). Although RT-PCR data indicated less than 2 rep copies (1.47 copies) per cell, the DNA hybridization pattern revealed that at least 2 copies of the rep gene were integrated as a head-to-tail concatemer producing, upon digestion with the single-cutter XbaI, a monomer fragment of the exact size of the linearized vector (Fig. 5). At 72 hr postinfection with Bac-rAAV-GFP (moi of 3), the number of copies of rep and cap genes increased up to 57 and 211, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 5, lanes marked F3/BacGFP). This further exhibits that a portion of the amplified molecular structures apparently incorporated a head-to-tail concatemers (Fig. 5, white double arrowhead). A lower discrete band of about 3.6 kbp (Fig. 5, black double arrowhead) is equimolar to the upper band, suggesting that it could be a junction fragment of the integrated concatemers in the amplified structure. It should be noted that the size of this fragment is equivalent to the distance between the XbaI recognition site and an RBE site upstream, which might indicate a Rep-dependent mechanism of the rescue and amplification. Indeed, in the absence of Rep (Fig. 5, lane E5/BacGFP), when cap-containing E5 cells are infected with Bac-rAAV-GFP, the lower band no longer appears in the rescued structure. When Rep was driven by the immediate early promoter ΔIE-1 (as in Bac-Rep helper), the effect of total and Rep-mediated amplification was much stronger, boosting the cap copy number per cell almost up to 1,200 (Table 1, Fig. 5, lane E5/BacRep). The precise molecular mechanism of the rescue/amplification requires further investigation.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of the rescue and amplification of the integrated rep and cap genes. (A) Southern blotting analysis of the integrated rep and cap genes in F3 (rep/cap) and E5 (cap) stable lines. The parental plasmids are digested with a single cutter (XbaI), per lane amounts loaded are equivalent to 500, 50, or 5 copies of the plasmid DNA in 5 μg of chromosomal DNA. Chromosomal DNA samples from uninfected (5 μg, lanes F3 and E5) or BEV-infected (0.5 μg, lanes F3/BacGFP, E5/BacGFP, and E5/BacRep) are digested with XbaI (a single-cutter, the positions of the XbaI sites are schematically shown below the respective panels), separated in an 1.2% agarose gel, transferred to a nylon filter, and hybridized to 32P-labeled rep or cap ORF DNA probes (left and right, respectively). White double arrowhead shows the form comigrating with a linearized parent plasmid vector; black double arrowhead indicates a position of a DNA fragment hypothetically derived from the Rep-mediated nicking at the RBE. Rep- and VP-encoding transcripts and their respective ORFs are diagrammed below the integrating cassettes. (B) Diagram depicting a postulated feed-forward loop. The transcription of both integrated rep and cap genes is induced by BEV-encoded IE-1 trans-regulator. One of the products, most likely Rep68/78 protein, returns to interact with RBE, inducing rescue/amplification and mediating the transcription.

Table 1.

Number of rep and cap genes in stable cell lines F3 (rep/cap) and E5 (cap) estimated by RT-PCR analysis

| Cell line |

rep |

cap |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (−) BEV | Bac-rAAV-GFP | (−) BEV | Bac-rAAV-GFP | Bac-Rep | |

| F3 | 1.47 | 57.44 | 4.02 | 211.29 | ND |

| E5 | NA | NA | 8.05 | 268.0 | 1199.48 |

ND, not determined; NA, not applicable.

Discussion

Although extremely promising, the original protocol of rAAV production in the baculovirus system has not been widely adopted. One of the main reasons is the complexity of the system involving 3 independent BEV helpers. According to the Poisson distribution (14), at the optimal moi of 3 (15), 95% of cells are infected with at least 1 BEV, but only 22.4% of cells are infected with 3 particles. At the higher moi, this ratio is reduced even further: for example, at an moi of 9 only 12.5% of the cells are infected with 9 particles. For rAAV production, cells are infected with the combination of 3 different BEVs, and the fraction of cells infected with all 3 helpers at the optimal ratio apparently is even lower (16). For example, solving the Poisson distribution for a particular combination of individual BEV helpers (e.g., 3:3:3) predicts the ratio of the respectively infected cells to be only 1.1%. The specifics of rAAV production also requires a coordinated and timely expression of 7 helper Rep and Cap proteins at the optimal stoichiometry (2, 5, 16, 17). Adding to the complexity of the system is the fact of the apparent instability of the recombinant BEVs, especially the Bac-Rep helper (5). In essence, rAAV production in insect cells poses technical challenges that are quite different from basic protein manufacturing. We sought to reduce the complexity by deriving a packaging stable cell line incorporating rep and cap helper genes. To this end, we used one of the critical genetic elements of the AcMNPV, a homologous region. Earlier Habib et al. (18) reported that AcMNPV hr1 enhances transcription from the polyhedrin promoter in a classic enhancer-like manner. Other BEV hrs have also been shown to display a potent enhancer function on exogenous and endogenous promoters in the absence of any viral trans-activator, suggesting that the binding of host factors might be involved in the enhancer mechanism (19). Considering the enhancing propensity of hrs to mediate transcription even without the BEV-encoded IE-1 factor, one would predict some basal level of transcription from the integrated rep genes. However, it appears that we have achieved a complete expression shutoff of both rep and cap ORFs positioned downstream of hr2-0.9 in the absence of BEV infection.

The mechanism by which DNA binding promotes IE-1 trans-activation is unknown. Olson et al. (13) hypothesized that DNA binding is required for conformational changes in IE-1, a prerequisite to subsequent interaction with other transcription factors and trans stimulation. However, binding to hr alone is insufficient for IE-1-mediated enhancer activity (20–22). Here, we show that upon infection with BEV, several proteins form complexes with P19 promoter, and some of these complexes apparently incorporate IE-1. It is unlikely that IE-1 directly binds to P19 because we were unable to identify the canonical IE-1 binding element within the tested P19 fragment. More likely, hr-bound IE-1 interacts with Sf9 host cell factors such as SP1 described recently in Sf9 cells, a transcription factor that was also shown to be capable of binding to the canonical SP1-response element from mammalian cells (23, 24). Incidentally, 2 SP1-binding sites (SP1–130 and SP1–50, Fig. 2A) were shown to be involved in regulation of transcription from AAV2 P19 promoter (9, 25). Hence, our working model of P19 activation includes insect host cell SP1 and BEV IE-1 bound to their respective response elements within P19 and hr2-0.9. Bound factors subsequently form a trans-activation complex via bent and looped-out DNA similar to what was described for AAV2 P5/P19 interaction (9, 26).

Interestingly, it appeared that the induced rep gene generated a complete set of Rep proteins including smaller Rep68 and Rep40, products of the spliced P5- and P19-derived transcripts. This seems to be a plausible scenario as splicing does occur for BEV-encoded ie-1 transcripts generating another immediate-early trans-regulator IE-0 (27). Moreover, even AAV2 rep- and cap-derived transcripts undergo splicing in Sf9 cells infected with BEVs (4). The Rep- and VP-expressing cassettes, therefore, emulate the WT AAV genome using hr and RBE DNA elements to up-regulate the internal P19 promoter, allowing high expression of the smaller Rep isoforms while still relying on the noncanonical ACG start codon for VP1 initiation (Fig. 5A).

One of the critical features of the described system is its propensity to rescue and amplify the integrated genes up to 1,200 copies per cell. The precise molecular mechanism of such amplification is a subject of a separate study. Nevertheless, it is clear that a feed-forward loop is initiated whereby Rep protein encoded by the integrated rep genes interacts with RBE to further enhance the helper cassette amplification and expression (Fig. 5B). Moreover, Rep might take part in the transcription initiation complex mediating P19 promoter activity in conjunction with IE-1. Although Rep is an integral part of rAAV production, the system can efficiently function without Rep protein (Fig. 5, Table 1) suggesting that its modular design could be used not only for the production of other AAV serotypes but also for unrelated multiprotein complexes.

In conclusion, we have designed a simple inducible expression system consisting of only 2 components: a stable Sf9-based cell line and a single BEV. To this end, we used, in an unconventional way, 2 genetic elements—hr2 from AcMNPV and RBE from AAV2—providing inducible expression of polh-driven rep78/68 and cap helper genes as well as P19-driven rep52/40. The arrangement provided a 10-fold higher yield of rAAV vectors compared with the original triple infection protocol.

Materials and Methods

Cloning of AcMNPV hr2.

WT AcMNPV was prepared as described previously (28), and the DNA sequence of hr2 [AcMNPV complete genome, nucleotides 26293–26961 GenBank accession no. NC_001623 (7)] was amplified by using a PCR-mediated protocol (SI Text). The band was cloned into pGEM-TEasy and sequence verified (GenBank accession no. FJ711701).

Mapping 5′-End of the rep52 Transcript.

We used the RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RLM-RACE) kit (Ambion). Cells from rep/cap BSR line F3 were propagated at 2 × 106 cells per mL and infected with recombinant Bac-rAAV-GFP (moi of 5). Seventy-two hours postinfection, cells were harvested and total RNA was isolated. AAV-specific primers (SI Text) were used in conjunction with the 5′RACE outer and inner control primers provided with the kit. The resulting PCR fragment was subcloned into pGEM-TEasy plasmid (Promega) and 10 random clones were sequenced.

Baculovirus Titering.

BEV titers were determined by a quantitative PCR assay developed in our laboratory. The assay is an adaptation of an alkaline PEG-based method for direct PCR (29). Briefly, 5 μL of baculovirus stock is added to 95 μL of alkaline PEG solution (PEG 200, pH 13.5) prepared as described earlier (29). After vortexing, the sample is incubated at room temperature for 15 min and then diluted 5-fold by adding 0.4 mL of water. Five microliters of this diluted mixture was used directly in an RT-PCR 25-μL reaction mixture containing 12.5 μL of SybrGreenER and 1.5 μL of 5 μM primers (SI Text). The sample is assayed side-by-side with a serially diluted reference standard, a BEV of a known titer. The amplified sequence is part of the AcMNPV gene Ac-IE-01, locus tag ACNVgp142, a putative early gene trans-activator; the size of the amplified DNA fragment is 103 bp.

Construction of Sf9 Stable Cell Lines.

To select and propagate cell lines, procedures previously described were followed (30). Blasticidin selection (25 μg/mL) was used for 3 weeks, after which antibiotics were omitted from the medium and cells were maintained in regular SFM (GIBCO/Invitrogen). To construct cell lines expressing all WT AAV2 proteins, Sf9 cells were cotransfected with undigested pIR-rep78-hr2-RBE and pIR-VPm11-hr2-RBE at the molar ratio of 1:2.5. In-house liposomes were used for the transfection. Screening for the most efficient packaging rep/cap cell line was performed with 106 cells from each clonal line infected with Bac-rAAV-GFP. At 72 hr postinfection, cells were harvested and subjected to 2 freeze/thaw cycles. Aliquots of the lysates were used to infect 293 cells. rep and cap lines were picked randomly and the protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting analysis in cells infected with BEV (Bac-rAAV-GFP for rep lines and Bac-Rep for cap lines).

RNA Isolation.

Total RNA from Sf9 cells was isolated by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) after on-column DNA digestion and concentration by using RNase-Free DNase Set and RNeasy Mini Elute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen). RNA integrity was verified by agarose gel (1.2%) electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining.

Western Blot Analysis.

Sf9 cells growing in SFM in suspension were harvested by centrifugation, washed with ice-cold PBS, and resuspended in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM EGTA supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture (Set 3) (Calbiochem). The suspension was incubated on ice for 1 hr and clarified by centrifugation for 30 min at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C in an Eppendorf 5417C tabletop centrifuge. Normalized for protein concentration, samples were separated by using 12% polyacrylamide/SDS electrophoresis, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with the anti-cap B1 monoclonal antibodies (1:4,000, generously donated by N. Muzyczka, University of Florida) or anti-Rep 11F monoclonal antibodies (1:4,000, a gift from N. Muzyczka), followed by ECL with anti-mouse IgG, horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (1:1000, Amersham Biosciences).

Electrophoretic Mobility-Shift Assay (EMSA).

EMSA was carried out as described previously (31). In brief, uninfected or BEV-infected (72 hr postinfection) Sf9 cells were harvested at 2 × 106 cells per mL and washed with ice-cold PBS. Packed cells were resuspended in 5 vol of hypotonic buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.9; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 10 mM KCl; 0.2 mM PMSF; 0.5 mM DTT) and allowed to swell on ice for 10 min. After homogenization in a glass Dounce homogenizer, nuclei were collected by centrifugation for 15 min at 3,300 × g. The nuclei were then resuspended in a high-salt buffer containing 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 0.7 M KCl; 0.2 mM EDTA; 0.2 mM PMSF; 0.5 mM DTT; and 25% glycerol. Nuclei were incubated for 30 min on ice and pelleted for 30 min at 25,000 × g. Aliquots of the supernatant were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Binding reactions (20 μL) containing 50 fmol of 32P-labeled DNA probe; 1 μg of poly(dI-dC); 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9; 100 mM KCl; 1 mM EDTA; 1 mM DTT; 12% glycerol; and 60 μg of nuclear extract were incubated for 30 min at 27 °C. In some instances, unlabeled DNA fragments were added into the assay for competition binding. Electrophoresis in a nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide (40:1 acrylamide/bisacrylamide) gel containing 2.5% glycerol was performed in 0.5× TBE at 30 mA for 2 hr; the contents of the gel were transferred onto DEAE filter paper, which was dried and exposed to x-ray film.

DNA Isolation and RT-PCR.

Total DNA from ≈5 × 106 cells was isolated by using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). One hundred nanograms of DNA was used for the quantification analysis by RT-PCR. DNA was amplified by using SybrGreenER qPCR Supermix (Invitrogen) and the specific primers (SI Text). For the calculations of the integrated gene copy number, the size of the Sf9 genome was assumed to be 400 Mb (32).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This research was supported by National Institute of Aging Grant AG10485 (to K.L. and S.Z.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. FJ711701).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0810614106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Berger I, Fitzgerald DJ, Richmond TJ. Baculovirus expression system for heterologous multiprotein complexes. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1583–1587. doi: 10.1038/nbt1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urabe M, Ding C, Kotin RM. Insect cells as a factory to produce adeno-associated virus type 2 vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:1935–1943. doi: 10.1089/10430340260355347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cecchini S, Negrete A, Kotin RM. Toward exascale production of recombinant adeno-associated virus for gene transfer applications. Gene Ther. 2008;15:823–830. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen H. Intron splicing-mediated expression of AAV Rep and Cap genes and production of AAV vectors in insect cells. Mol Ther. 2008;16:924–930. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohlbrenner E, et al. Successful production of pseudotyped rAAV vectors using a modified baculovirus expression system. Mol Ther. 2005;12:1217–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guarino LA, Gonzalez MA, Summers MD. Complete sequence and enhancer function of the homologous DNA regions of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J Virol. 1986;60:224–229. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.1.224-229.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayres MD, et al. The complete DNA sequence of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology. 1994;202:586–605. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarvis DL, Weinkauf C, Guarino LA. Immediate-early baculovirus vectors for foreign gene expression in transformed or infected insect cells. Protein Expr Purif. 1996;8:191–203. doi: 10.1006/prep.1996.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lackner DF, Muzyczka N. Studies of the mechanism of transactivation of the adeno-associated virus p19 promoter by Rep protein. J Virol. 2002;76:8225–8235. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.16.8225-8235.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nony P, et al. Novel cis-acting replication element in the adeno-associated virus type 2 genome is involved in amplification of integrated rep-cap sequences. J Virol. 2001;75:9991–9994. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9991-9994.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zolotukhin S. Production of recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:551–557. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen L, Spector DJ. Local character of readthrough activation in adenovirus type 5 early region 1 transcription control. J Virol. 2003;77:9266–9277. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9266-9277.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olson VA, Wetter JA, Friesen PD. The highly conserved basic domain I of baculovirus IE1 is required for hr enhancer DNA binding and hr-dependent transactivation. J Virol. 2003;77:5668–5677. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.5668-5677.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devore JL. Probability and Statistics for Engineering and the Sciences. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole–Thomson Learning; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen LK. Virus production from cell culture, kinetics. In: Spier RE, editor. The Encyclopedia of Cell Technology. New York: Wiley; 2000. pp. 1217–1230. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aucoin MG, Perrier M, Kamen AA. Production of adeno-associated viral vectors in insect cells using triple infection: Optimization of baculovirus concentration ratios. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;95:1081–1092. doi: 10.1002/bit.21069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urabe M, et al. Scalable generation of high-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus type 5 in insect cells. J Virol. 2006;80:1874–1885. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1874-1885.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Habib S, et al. Bifunctionality of the AcMNPV homologous region sequence (hr1): Enhancer and ori functions have different sequence requirements. DNA Cell Biol. 1996;15:737–747. doi: 10.1089/dna.1996.15.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu M, Farrell PJ, Johnson R, Iatrou K. A baculovirus (Bombyx mori nuclear polyhedrosis virus) repeat element functions as a powerful constitutive enhancer in transfected insect cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30724–30728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guarino LA, Dong W. Functional dissection of the Autographa california nuclear polyhedrosis virus enhancer element hr5. Virology. 1994;200:328–335. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leisy DJ, Rohrmann GF. The Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus IE-1 protein complex has two modes of specific DNA binding. Virology. 2000;274:196–202. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodems SM, Friesen PD. The hr5 transcriptional enhancer stimulates early expression from the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus genome but is not required for virus replication. J Virol. 1993;67:5776–5785. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.5776-5785.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramachandran A, et al. Novel Sp family-like transcription factors are present in adult insect cells and are involved in transcription from the polyhedrin gene initiator promoter. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23440–23449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasheedi S, Ramachandran A, Ehtesham NZ, Hasnain SE. Biochemical characterization of Sf9 Sp-family-like protein factors reveals interesting features. Arch Virol. 2007;152:1819–1828. doi: 10.1007/s00705-007-1017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pereira DJ, Muzyczka N. The cellular transcription factor SP1 and an unknown cellular protein are required to mediate Rep protein activation of the adeno-associated virus p19 promoter. J Virol. 1997;71:1747–1756. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1747-1756.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira DJ, Muzyczka N. The adeno-associated virus type 2 p40 promoter requires a proximal Sp1 interaction and a p19 CArG-like element to facilitate Rep transactivation. J Virol. 1997;71:4300–4309. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4300-4309.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chisholm GE, Henner DJ. Multiple early transcripts and splicing of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus IE-1 gene. J Virol. 1988;62:3193–3200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.9.3193-3200.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Reily DR, Miller LK, Luckow VA. Baculovirus Expression Vectors: A Laboratory Manual. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chomczynski P, Rymaszewski M. Alkaline polyethylene glycol-based method for direct PCR from bacteria, eukaryotic tissue samples, and whole blood. BioTechniques. 2006;40:454, 456, 458. doi: 10.2144/000112149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrison RL, Jarvis DL. Transforming lepidopteran insect cells for continuous recombinant protein expression. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;388:299–316. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-457-5_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buratowski S, Chodosh LA. Mobility shift DNA-binding assay using gel electrophoresis. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2001;2:12.2. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1202s36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.d'Alencon E, et al. A genomic BAC library and a new BAC-GFP vector to study the holocentric pest Spodoptera frugiperda. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theilmann DA, Stewart S. Identification and characterization of the IE-1 gene of Orgyia pseudotsugata multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology. 1991;180:492–508. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90063-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasmussen C, Leisy DJ, Ho PS, Rohrmann GF. Structure-function analysis of the Autographa californica multinucleocapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus homologous region palindromes. Virology. 1996;224:235–245. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zolotukhin S, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus purification using novel methods improves infectious titer and yield. Gene Ther. 1999;6:973–985. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.