Abstract

Biosynthesis of NAD(P) in bacteria occurs through either the de novo or one of the salvage pathways which converge at the point where the reaction of nicotinate mononucleotide (NaMN) with adenosine triphosphate (ATP), is coupled to the formation of nicotinate adenine dinucleotide (NaAD) and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi). This reaction is catalyzed by nicotinate mononucleotide adenylyltransferase (NMAT) which is essential for bacterial growth making it an attractive drug target for the development of new antibiotics. Steady-state kinetic and direct binding studies on NMAT from Bacillus anthracis suggest a random sequential Bi-Bi kinetic mechanism. Interestingly, the interactions of NaMN and ATP with NMAT were observed to exhibit negative cooperativity, i.e. Hill coefficients < 1.0. Negative cooperativity in binding is also supported from X-ray crystallographic studies. X-ray structures of the B. anthracis NMAT apoenzyme, and the NaMN and NaAD-bound complexes were determined to resolutions of 2.50 Å, 2.60 Å and 1.75 Å, respectively. The X-ray structure of the NMAT-NaMN complex revealed only one NaMN molecule bound in the biological dimer supporting negative cooperativity in substrate binding. The kinetic, direct-binding, and X-ray structural studies support a model whereby the binding affinity of substrates to the first monomer of NMAT is stronger than to the second and analysis of the three X-ray structures reveals significant conformational changes of NMAT along the enzymatic reaction coordinate. The negative cooperativity observed in B. anthracis NMAT substrate binding is a unique property that has so far not yet been observed in other prokaryotic NMAT enzymes. We propose that regulation of the NAD(P) biosynthetic pathway may in part occur at the reaction catalyzed by NMAT.

Keywords: Bacillus anthracis, negative cooperativity, NAD, regulation, pathway, conformational change, reaction coordinate

INTRODUCTION

Anthrax infections are caused by the gram-positive, endospore-forming, rod-shaped bacterium Bacillus anthracis 1. Inhalational anthrax infections can have a 90% mortality rate even when treated with conventional antibiotic therapies 1. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention categorize B. anthracis as a category A bioterrorism agent, the highest priority, due to its potential for causing mass casualties 2. The impending threat of bioterrorism attack and the feasibility of the development of multi-drug resistant strain of B. anthracis amplifies the need for the development of novel antibiotics 3; 4; 5; 6.

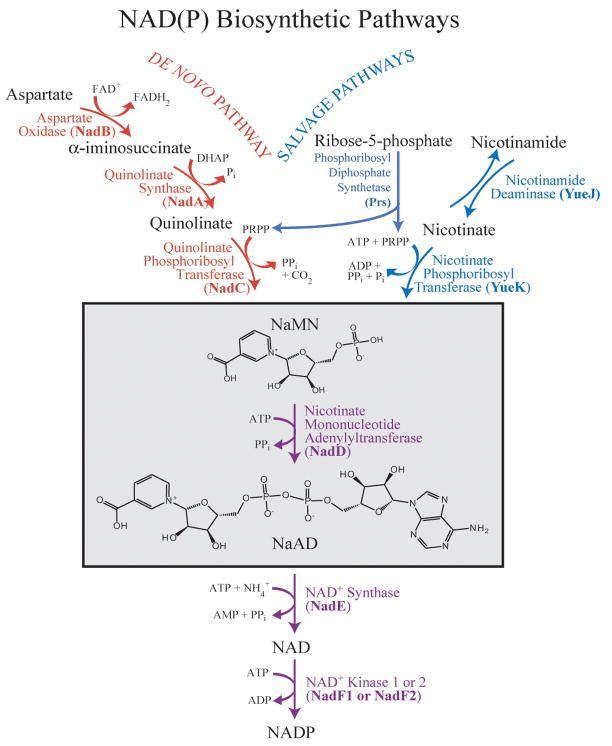

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides (NAD and NADP) are ubiquitous cofactors that are essential to all living systems. The importance of these cofactors lies in the fact that they are used in hundreds of redox reactions throughout the cell and as a result, they have an impact on virtually every cellular metabolic pathway 7. In bacteria, biosynthesis of NAD(P) occurs through either the de novo or by salvaging of precursors (Figure 1) 8. These pathways converge at the point where the reaction of nicotinate mononucleotide (NaMN) with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is coupled to the formation of nicotinate adenine dinucleotide (NaAD) and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi). This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme nicotinate mononucleotide adenylyltransferase (NMAT). NMAT is a member of the nucleotidyltransferase α/β phosphodiesterase superfamily which possess a conserved HXGH signature motif and are characterized by the presence of a Rossmann fold 9. Members of this superfamily include glycerol-3-phosphate cytidylyltransferase (GCT) and sulfate adenylyltransferase 10; 11. The reaction catalyzed by NMAT and other members of the superfamily is believed to proceed through a nucleophilic attack by the 5′ phosphate of the mononucleotide (in the case of sulfate adenylyltransferase, the sulfate) on the α-phosphate of the triphosphate 12.

Figure 1. Bacterial NAD(P) biosynthetic pathway.

The de novo pathway (shown in red) begins with aspartate, while the salvage pathway (shown in blue) uses either nicotinamide or nicotinate mononucleotide as its starting substrate. The reaction catalyzed by NMAT sits at the branch point between the two pathways (outlined with a box). Gene names are shown in parentheses. Abbreviations used: DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; PRPP, 5-phospho-ribose-1-pyrophosphate; NaMN, nicotinate mononucleotide; NaAD, nicotinate adenine dinucleotide; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NADP, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate.

NMAT has been determined to be essential in numerous bacterial systems including Bacillus subtilis 8; 13; 14; 15. Gerdes et al. have identified and ranked several putative antibacterial drug targets based on a combination of genetic footprinting using E. coli as a model system, and comparative genome analysis using various gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria such as B. anthracis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa 9. The ranking was based on three criteria: 1) range of pathogens containing the target enzyme, 2) sequence similarity of the target enzyme among the pathogens, and 3) sequence similarity of the target enzyme to its human counterpart. Based on these criteria, it was determined that NMAT is a preferred target and therefore is attractive for the development of new antibiotics.

Here we report a detailed kinetic analysis of the B. anthracis NMAT kinetic mechanism through initial rate and product inhibition studies in conjunction with isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments. The data provide evidence of negative cooperativity in substrate binding to B. anthracis NMAT. We propose that the NAD/P biosynthetic pathway may be regulated in part through NMAT. The negative cooperativity observed in B. anthracis NMAT substrate binding is a unique property of the enzyme that has so far not yet been observed in other prokaryotic NMAT enzymes. In order to obtain an understanding of the interactions and conformational changes associated with ligand binding, we determined the x-ray structures of B. anthracis as an apoenzyme, and as complexes with the substrate NaMN and the product NaAD.

RESULTS

Purification of (His)6-tagged and native NMAT enzymes

B. anthracis NMAT was cloned from genomic DNA, overexpressed and purified to homogeneity from E. coli cells as both the native enzyme and as a fusion protein containing an N-terminal (his)6 tag. The NMAT(his)6-tag construct was purified in a single step using a metal chelate affinity column. The native NMAT construct was purified using three steps that included a 40% ammonium sulfate fractionation, a phenyl sepharose, hydrophobic-interaction column and a strong anion-exchange column. The final purification yields were 200 mg per liter of Luria-Bertani (LB) culture for the (his)6-tag and 75 mg per liter for the native NMAT enzymes. The final purity for each enzyme was >95% based on SDS-PAGE analysis (Supplemental Figure 1). Both the (his)6-tag NMAT and the native NMAT proteins were stable with negligible loss of activity for at least 6 months when stored at −80°C.

Kinetic analysis of NMAT

Two assays were utilized to determine the steady-state kinetic parameters kcat, K0.5, and nH for the NMAT catalyzed reaction. The first assay was a continuous assay based on the EnzChek pyrophoshate assay kit 16. In this assay the inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) product released from the reaction catalyzed by NMAT is hydrolyzed into two molecules of inorganic phosphate (Pi) by inorganic pyrophosphatase (IPP). Purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) then converts one molecule of Pi and one molecule of 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine ribonucleoside (MESG) into ribose 1-phosphate and 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine, which can be monitored by the increase in absorption at 360 nm. This coupled reaction allows for the quantization of Pi consumed in the reaction, which is proportional to the PPi produced by NMAT.

The second assay utilized was a discontinuous HPLC assay which allows for the separation of both substrates, ATP and NaMN, from the products, NaAD and PPi in less than 2 minutes using a C18 reverse phase column (Supplemental Figure 2). This assay was used to corroborate the kinetic results obtained with the coupled-enzyme assay and to confirm that the presence of negative cooperativity was not due to an artifact associated with the coupling enzymes IPP and PNP utilized in the continuous assay. Unlike the continuous assay, the HPLC-based discontinuous assay does not require the presence of other enzymes which could potentially interfere with NMAT kinetic analysis.

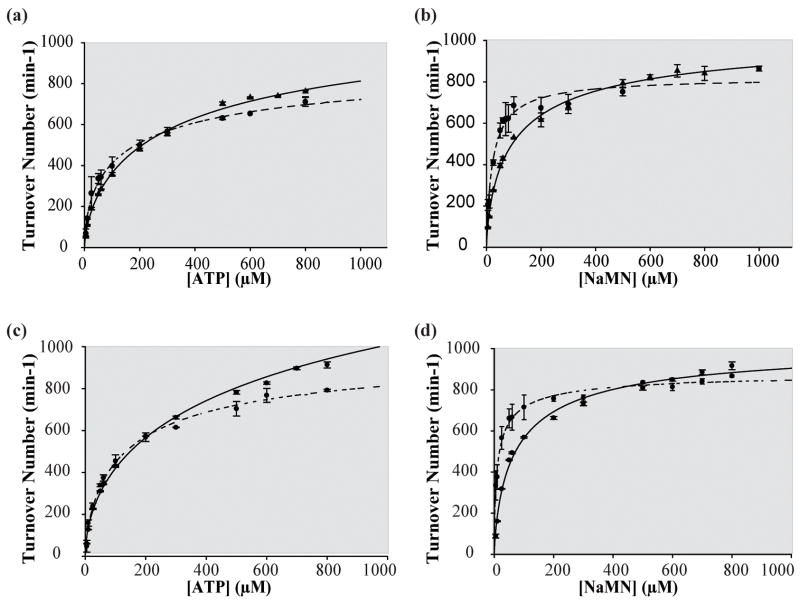

We first determined whether the N-terminal (his)6-tag on NMAT has an effect on the enzymatic activity. The kinetic responses of native NMAT to substrate binding are compared to those of (his)6-NMAT in Figure 2. No significant differences in the kinetic parameters, summarized in Table 1, were observed indicating the N-terminal (his)6 has no effect on NMAT kinetics. Therefore, the (his)6-NMAT enzyme was used for all subsequent experiments due to the ease of protein purification. From this point on, we will refer to (his)6-NMAT as NMAT. The pH optimum of NMAT was determined to be between 6.75 – 7.75 (Supplemental Figure 3). Therefore, detailed kinetic experiments were performed at a pH of 7.5.

Figure 2. Comparison of continuous and discontinuous activity assays for (His)6-tag and native B. anthracis NMAT.

(a) The (His)6-tag B. anthracis NMAT ATP kinetics performed at 11 different [ATP] ranging from 5–800 μM and fixed [NaMN] at 600 μM using both the discontinuous (solid line) and continuous (dashed line) activity assays. (b) The (His)6-tag B. anthracis NMAT NaMN kinetics performed at 11 different [NaMN] ranging from 5–800 μM and fixed [ATP] at 600 μM using both the discontinuous (solid line) and continuous (dashed line) activity assays. (c) The native B. anthracis NMAT ATP kinetics performed at 11 different [ATP] ranging from 5–800 μM and fixed [NaMN] at 600 μM using both the discontinuous (solid line) and continuous (dashed line) activity assays. (d) The native B. anthracis NMAT NaMN kinetics performed at 11 different [NaMN] ranging from 5–800 μM and fixed [ATP] at 600 μM using both the discontinuous (solid line) and continuous (dashed line) activity assays.

Table 1.

Comparison of the kinetic parameters of B. anthracis (his)6-tag and Native NMAT.

| Assay | Substrate | Construct | K0.5 (μM) | kcat (min−1) | nH | AICce |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Assay | NaMNa | (His)6-Tag | 21 ± 1c | 966 ± 15c | 0.803 ± 0.004c | 212.9 |

| 18 ± 1d | 918 ± 9d | 230.6 | ||||

| ATPb | 142 ± 28c | 1022 ± 58c | 0.699 ± 0.005c | 231.9 | ||

| 79 ± 6d | 841± 16d | 252.5 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| NaMNa | Native | 16 ± 1c | 815 ± 12c | 0.806 ± 0.004c | 227.2 | |

| 15 ± 1d | 782 ± 7d | 239.2 | ||||

| ATPb | 169 ± 79c | 973 ± 120c | 0.621 ± 0.007c | 213.7 | ||

| 59 ± 7d | 702 ± 20d | 229.4 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Discontinuous Assay | NaMNa | (His)6-Tag | 79 ± 10c | 1039 ± 36c | 0.750 ± 0.005c | 244.4 |

| 54 ± 3d | 918 ± 13d | 262.5 | ||||

| ATPb | 479 ± 95c | 1569 ± 94c | 0.624 ± 0.023c | 195.3 | ||

| 124 ± 9d | 1006 ± 20d | 266.7 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| NaMNa | Native | 110 ± 18c | 1059 ± 49c | 0.708 ± 0.004c | 154.9 | |

| 65 ± 5d | 890 ± 16d | 175.1 | ||||

| ATPb | 378 ± 109c | 1240 ± 111c | 0.661 ± 0.004c | 224.2 | ||

| 129 ± 10d | 864 ± 19d | 259.1 | ||||

Kinetic parameters determined at saturating concentrations of ATP

Kinetic parameters determined at saturating concentrations of NaMN

Data fit to Hill equation

Data fit to Michaelis-Menten equation

Akaike Information Criterion

The kinetic data presented in Figure 2 were fit to both the Hill and Michaelis-Menten equations. Based on the statistics of the resulting non-linear curve fits, the data were best-fit to the Hill equation. The Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) value was used to distinguish between these models. The AICc is a measure of the goodness-of-fit of a particular dataset to a model. A lower or more negative AICc value for a model compared to a competing model is indicative of a better fit. A difference of more than 7 is considered statically significant. The AICc values for the Hill and Michaelis-Menten kinetic models indicated that the data fit better to the Hill equation (Table 1).

Comparison of the kinetic parameters, kcat, K0.5, and nH, determined using the continuous and discontinuous assays reveals slightly different values for all three parameters for both substrates (Table 1). The continuous assay produced kcat, K0.5 and nH values for ATP of 1022 ± 58 min−1, 142 ± 28 μM and 0.699 ± 0.005 respectively, while the discontinuous assay gave values of 1569 ± 94 min−1, 479 ± 95 μM and 0.624 ± 0.023 (Figure 2(a), Table 1). The kinetic parameters, kcat, K0.5 and nH for NaMN using the continuous assay were determined to be 996 ± 15 min−1, 21 ± 1 μM and 0.803 ± 0.004, , while the discontinuous HPLC assay produced values of 1039 ± 36 min−1, 79 ± 10 μM and 0.750 ± 0.005 (Figure 2(b), Table 1). An approximate 4-fold difference was observed in the kinetic parameter K0.5 for both ATP and NaMN between the two assays. In the continuous assay the product of the NMAT reaction, PPi, is being continually removed, thereby preventing the reverse reaction from occurring. In the discontinuous assay, the reverse reaction is able to take place since both products, NaAD and PPi, rapidly increase in concentration. This may explain the difference observed in the K0.5 values for both ATP and NaMN since the substrates would be competing with the products for binding.

The discontinuous assay was also used to study the reversibility of the NMAT reaction (data not shown). However, the kinetic parameters of the reaction could not be determined since a linear, steady-state response of NMAT could not be obtained. From the HPLC assay it is clear that the reverse reaction is very rapid due to the fact that a rapid increase in the amount of ATP produced is observed shortly after reaction initiation. The data in Figure 2 indicate that for the discontinuous assay (solid line) saturation cannot be as readily achieved as in the continuous assay (dashed lines) as higher substrate concentrations are employed. This observation is reflected in the lower Hill coefficient values obtained from the discontinuous assay and would be consistent with the products building up more rapidly when using this assay which would thereby affect the initial rates by lowering them due to product inhibition. The net effect of this inhibition would be to increase the K0.5 values for both ATP and NaMN derived from the discontinuous assay which is observed (Table 1).

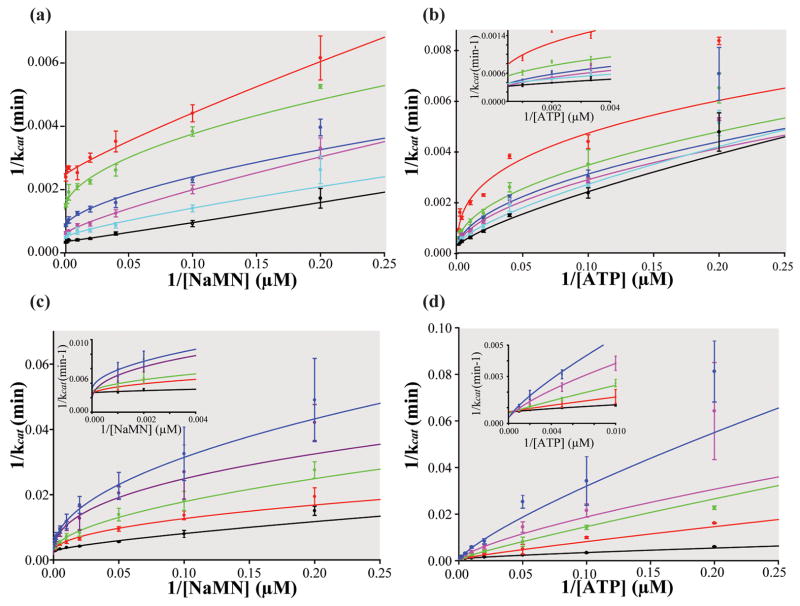

Due to the relative ease of carrying out the continuous assay versus the discontinuous assay and the ability to continually remove PPi from the solution thereby preventing the reverse reaction, a detailed bi-reactant initial velocity study of NMAT kinetics was performed using the former assay to monitor enzymatic activity. The kinetic patterns of such studies allow for discrimination between the two basic types of bi-substrate reactions, the ping-pong mechanism or the sequential mechanism 17. Figure 3(a) shows the initial velocity study in which NaMN was varied between 10 μM – 1000 μM and ATP was held constant at 6 different concentrations. Figure 3(b) shows the reciprocal initial velocity study in which ATP was varied between 10 μM – 1000 μM and NaMN was held constant at 6 different concentrations. The downward curvature observed in Lineweaver-Burk plots of the initial velocity experiments reveal that NMAT exhibits negative cooperativity in binding of substrates under the conditions used in the assays, yet to varying degrees (Figure 3(a) &(b)).

Figure 3. Kinetic mechanism of B. anthracis NMAT.

Insets show the y-intercepts. (a) Lineweaver-Burk plot of initial rates of product formation at variable [NaMN]’s and six fixed [ATP]. Red: 10 μM ATP, Green: 25 μM ATP, Blue: 50 μM ATP, Purple: 100 μM ATP, Cyan: 300 μM ATP, and Black: 1 mM ATP. (b) Lineweaver-Burk plot of initial rates of product formation at variable [ATP] and six fixed [NaMN]. Red: 10 μM NaMN, Green: 25 μM NaMN, Blue: 50 μM NaMN, Purple: 100 μM NaMN, Cyan: 300 μM NaMN, and Black: 1 mM NaMN (c) Lineweaver-Burk plot of product inhibition with five, fixed [NaAD] (Black: no NaAD, Red: 5 μM NaAD, Green: 25 μM NaAD, Purple: 50 μM NaAD, and Blue: 100 μM NaAD), variable [NaMN], and fixed [ATP] at 50 μM. (d) Lineweaver-Burk plot of product inhibition with five, fixed [NaAD] (Black: no NaAD, Red: 5 μM NaAD, Green: 25 μM NaAD, Purple: 50 μM NaAD, and Blue: 100 μM NaAD), variable [ATP], and fixed [NaMN] at 40 μM. Negative cooperativity is seen by the downward curvature in the Lineweaver-Burk plots.

At low concentrations of NaMN, the slopes of the Lineweaver-Burk plots (K0.5/kcat) decrease with increasing concentrations of ATP (Figure 3(a)). In addition, at high concentrations of NaMN and increasing concentrations of ATP, an increase in kcat occurs (see y-intercept of Figure 3(a)), which is indicative of a sequential mechanism. As is also expected for a sequential mechanism, this trend is observed in the reciprocal experiment, in which ATP is the variable substrate and the NaMN concentration is fixed (Figure 3(b)). Together the kinetic results support a sequential kinetic mechanism for B. anthracis NMAT with observed negative cooperativity.

In order to further characterize the kinetic mechanism in terms of preferred substrate binding order, the patterns of inhibition by the reaction product, NaAD, were examined. The observed effect of fixed concentrations of NaAD on the condensation of NaMN and ATP as a function of different concentrations of NaMN (varied between 5 μM – 1000 μM) indicates competitive inhibition (Figure 3(c)). When ATP is the variable substrate (varied between 5 μM – 1000 μM), the patterns obtained are also consistent with competitive inhibition by NaAD (Figure 3(d)). These patterns of competition between the product, NaAD, and the substrates, ATP and NaMN, correlate well with our hypothesis of a random sequential Bi-Bi mechanism. The downward curvature in these plots also suggests negative cooperativity in the interaction of substrates with NMAT.

The presence of negative cooperativity prompted us to investigate whether or not the B. anthracis NMAT reaction is influenced by potential effector molecules within the NAD/P biosynthetic pathway (Figure 1). The following compounds were tested for their ability to activate or inhibit the NMAT reaction: L-aspartic acid, quinolic acid, NAD, NADP, 5-phospho-ribose-1-pyrophosphate (PRPP), dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), AMP, and ADP (Data not shown). None of these compounds were observed to have an effect on NMAT activity, indicating that regulation of NMAT activity may occur directly through its own substrate and product concentrations. It is of course possible that other untested molecules within the NAD(P) biosynthetic pathway or from closely associated pathways could regulate the NMAT reaction.

Direct Binding Studies of NMAT Substrates via ITC

The dissociation constants for NaMN, NaAD, and ATP-Mg2+ to free NMAT were measured using ITC. Since the product inhibition studies support a random sequential Bi-Bi mechanism, all substrates and products would be predicted to bind to free enzyme. The kinetic studies also revealed the presence of negative cooperativity, which can sometimes be observed in ITC experiments. Negative cooperativity can be suggested via ITC binding isotherms which exhibit shapes consistent with either the weakening of the apparent affinities as ligand concentrations are increased saturation at a binding site stoichiometry less than the total number of binding sites e.g. half-sites binding 18. Isothermal titrations of the substrates NaMN and ATP into NMAT resulted in apparent weakening of ligand affinities as the concentration of either NaMN or ATP were increased, consistent with the kinetic experiments. Attempts were made to fit titration data to three different models, one set of binding sites, two sets of individual binding sites, and sequential binding sites. The NaMN and ATP data were best fit to the sequential binding site model since it was the only model to converge at a solution. Both sets of data produced dissociation constants that were weaker for the second binding site. The dissociation constants for NaMN and ATP binding to the first sites were 382 ± 38 μM and 215 ± 35 μM, respectively. The dissociation constants for NaMN and ATP binding to the second sites were 9280 ± 9 μM and 3716 ± 19 μM. Since the dissociation constants of the second sites were in the millimolar range, bi-phasic titration curves are not observed (Figure 4(a), (b): Table 2).

Figure 4. ITC Analysis of B. anthracis NMAT.

(a) Titrations of 167 μM NMAT with 20 mM NaMN shown in the top panel, with data fit to the sequential binding site model in the bottom panel (solid squares)(solid circles show the control of 20 mM NaMN into buffer). (b) Titrations of 167 μM NMAT with 20 mM ATP and 25 mM MgCl2 shown in the top panel, with data fit to the sequential binding site model in the bottom panel (solid squares)(solid circles show the control of 20 mM ATP and 25 mM MgCl2 into buffer). (c) Titrations of 167 μM NMAT 4 mM NaAD shown in the top panel, with data fit to the single site binding model in the bottom panel. The heat of dilution was determined by averaging the last 8 injections.

Table 2.

ITC parameters measured for B. anthracis NMAT

| Substrate | KD (μM) | ΔH (cal/mol) | ΔS (cal/mol*K) | Stoichiometry to monomer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaMN | KD1= 382± 38 | ΔH1= −5385 ± 47 | ΔS1= −2.4 | n/a |

| KD2= 9208 ± 9 | ΔH2= −3954 ± 183 | ΔS2= −3.9 | n/a | |

| ATP-Mg2+ | KD1= 215 ± 35 | ΔH1= −5348 ± 216 | ΔS1= −1.2 | n/a |

| KD2= 3716 ± 19 | ΔH2= −1.4E4 ± 350 | ΔS2= −36 | n/a | |

| NaAD | 3.2 ± 0.8 | −6446 ± 30 | ΔS=3.5 | 0.924 ± 0.003 |

n/a In the sequential binding site model stoichiometry is assumed to be 1.

The titration of the product, NaAD, resulted in a typical binding isotherm and the data were fit to a single site binding model with a dissociation constant of 3.2 ± 0.8 μM and a binding stoichiometry of 0.924 ± 0.003 (Figure 4(c), Table 2). Since the binding stoichiometry was 1 to 1, there is no negative cooperativity associated with NaAD binding to NMAT. This result is also supported from the crystallographic studies presented below, since both binding sites of the NMAT dimer are occupied with NaAD molecules.

X-ray structure of NMAT

The X-ray structure of the B. anthracis NMAT apoenzyme was determined to a resolution of 2.50 Å with a figure-of-merit (FOM) of 0.792, Rfree of 26.2 %, and a Rcrsyt of 21% using molecular replacement and the B. Subtilis NMAT X-ray structure (PDB identifier: 1KAM) as a search model (Table 3) 16. The apoenzyme of NMAT crystallizes in the P61 space group with two monomers in the asymmetric unit forming a homodimer with chains A and B. In order to determine if NMAT was a dimer in solution, the oligomeric state of NMAT was determined using analytical size exclusion chromatography. NMAT eluted off the column as a single peak, with an apparent molecular weight of 46.7 kDa, corresponding to a dimer (calculated MW 48.4 kDa) (Data not shown). The dimer is formed through a handshake association of the two monomers which creates a pseudo-2-fold symmetry centered on two antiparallel β-strands (β-strand 7), each contributed by one monomer (Figure 5).

Table 3.

Data collections and refinement statistics

| NMAT Complex | Apo | NaMN bound | NaAD bound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | |||

| Space Group | P61 | P61 | C2221 |

| Unit Cell dimensions: | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | a=b=97.026, c=85.095 | a=b=95.895, c=84.532 | 142.87, 103.07, 91.73 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.5 | 2.6 | 1.75 |

| No. reflection recorded | 92,086 | 74,602 | 277,908 |

| No. averaged reflections | 14,956 | 13,586 | 68,050 |

| Rmerge (%) | 8.3(45.8) | 8.2(65.1) | 5.3(35.0) |

| I/σI | 25.7(2.6) | 27.6(2.7) | 37.8(2.3) |

| % Completenessa | 94.7(93.1) | 99.8(98.3) | 97.6(83.9) |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution Range | 20.0 – 2.5 | 20.0 – 2.6 | 20.0 – 1.75 |

| No. Reflections in Working Set | 14,226 | 12,955 | 64,585 |

| No. Reflections in Test Set | 735 | 658 | 3,465 |

| Rcryst (%)b | 21 | 20.4 | 21.9 |

| Rfree (%)c | 26.2 | 28.4 | 25.7 |

| Figure of meritd | 0.792 | 0.774 | 0.804 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 44 | 51.4 | 32.9 |

| No. water molecules | 125 | 130 | 417 |

| No. glycerol molecules | 4 | 6 | 0 |

| No. NaMN molecules | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| No. Co2+ molecules | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| No. NaAD molecules | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| No. sulfate molecules | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| RMSD from ideal geometry: | |||

| Bond Lengths (Å) | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.010 |

| Bond Angles (degrees) | 1.47 | 1.5 | 1.43 |

| Dihedral angles (degrees) | 23.4 | 23.2 | 22.6 |

| Improper angles (degrees) | 1.02 | 1.06 | 2.7 |

| Ramachandran Plot | |||

| Most Favored (%) | 97.9 | 98.8 | 100 |

| Allowed (%) | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0 |

Completeness for I/σ(I) >1.0, high-resolution shell in parentheses.

Rcryst = Σ || Fo |−|Fc ||/Σ| Fo |

Rfree was calculated against 5% of the reflections removed at random

Figure of merit = (| ΣP (α)eiα/ΣP (α) |), where α is the phase and P(α) is the phase probability distribution

Figure 5. Overall architecture of B. anthracis NMAT and overlay with B. subtilis NMAT.

(a) Ribbon diagram of the functional dimer of NMAT. The Rossman folds of chain A and B are shown in cyan and green, respectively. The C-terminal helical domains of chains A and B are colored yellow and orange, respectively. (b) Overlay of B. anthracis NMAT (shown in cyan) and B. subtilis NMAT (shown in purple) showing the replacement of the small helical turn in B. subtilis NMAT with helix D of B. anthracis NMAT shown in red. The small helical turn in B. anthracis NMAT is shown in dark blue.

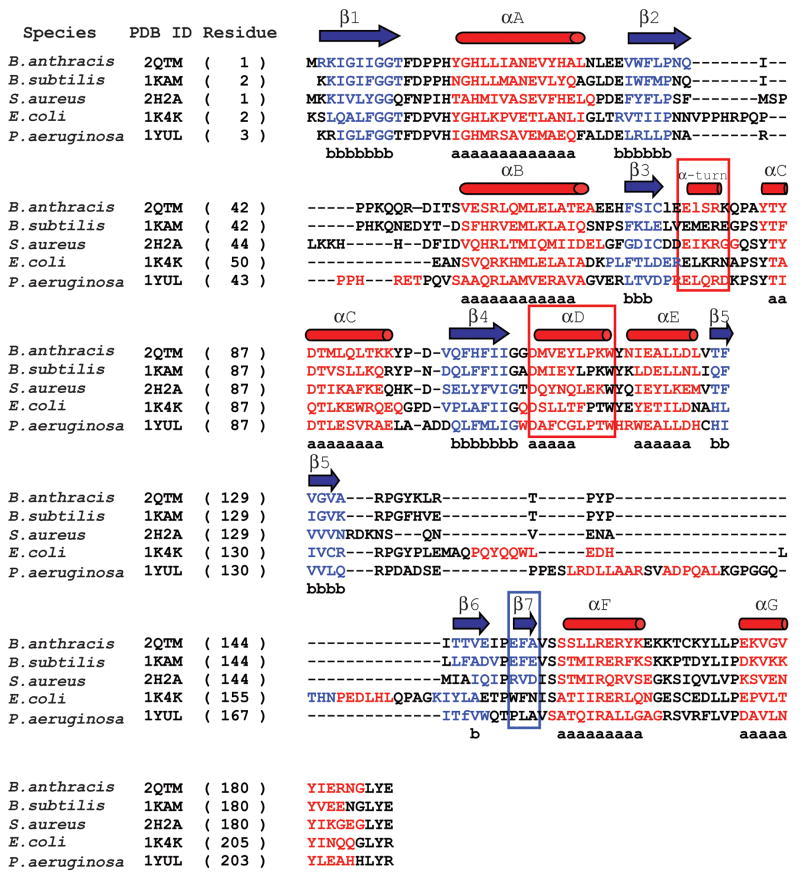

Each monomer of the B. anthracis NMAT enzyme contains a small C-terminal helical domain and a larger N-terminal domain which forms a modified, nucleotide-binding Rossmann fold (Figure 5(a)) 9; 19. The Rossmann fold is a characteristic of the nucleotidyltransferase α/β phosphodiesterase superfamily and is composed of a tightly twisted, parallel β-sheet formed by six β-strands of the order: 3-2-1-4-5-6 (Figure 5(a)). In the B. anthracis NMAT structure, α-helices A and B sit below the central β-sheet, while α-helices C, D, and E sit above it (Figure 5(a)). The Rossmann fold of B. subtilis NMAT contains the same overall architecture, but with one less α-helix (helix D in Figure 5(b) and Figure 6) above the central β-sheet. In the B. subtilis NMAT structure, α-helix D, observed in the B. anthracis NMAT structure, is replaced by a small α-helical turn (Figure 5(b) and Figure 6) 16. NMAT enzymes from the gram-positive bacteria including B. anthracis, B. subtilis, and Staphylococcus aureus contain an additional β-strand (β-strand 7 in the B. anthracis structure) that is involved in ligand recognition and dimer interface interactions (Figure 6). This β-strand is not observed in NMAT structures from gram-negative bacteria, archea, or eukaryotes (Figure 6) 12; 16; 20; 21. The final 30 amino acids of the C-terminus of B. anthracis NMAT form two α-helices (F and G) which form the small helical domain.

Figure 6. Structure-based sequence alignment of bacterial NMAT’s.

A structure-based sequence alignment of the B. anthracis NMAT with B. subtilis NMAT, S. aureus NMAT, E. coli NMAT, and P. aeruginosa NMAT. B. anthracis NMAT secondary structure is shown above the alignment, where blue arrows and red cylinders denote β-sheets and α-helices, respectively. Residues involved in β-sheet and α-helix formation are colored blue and red, respectively. Black colored residues represent loop regions. Lower case “b’s” represent conserved β-sheet formation and lower case “a’s” represent conserved α-helix formation. The red boxes represent the secondary structural elements that are different between B. anthracis and B. subtilis NMAT structures. The blue box indicates the different secondary structural elements between gram (−) and gram (+) bacteria. This figure was generated using STRAP (http://www.charite.de/bioinf/strap/) and the secondary structure of B. anthracis NMAT was manually added. STRAP inserted many unnecessary gaps and therefore for clarity the gaps were removed in the region of the α-helix D.

X-ray structure of the NaMN bound-complex

The crystal structure of NMAT bound with the substrate, NaMN, was determined to explore the allosteric mechanism, protein-ligand interactions, and conformational changes of B. anthracis NMAT upon substrate binding. The NMAT-NaMN complex also crystallized in space group P61, and the structure was determined to a resolution of 2.60 Å (Table 3). The X-ray structure revealed two monomers; chains A and B, in the asymmetric unit, and these chains formed a dimer similar to the apoenzyme structure.

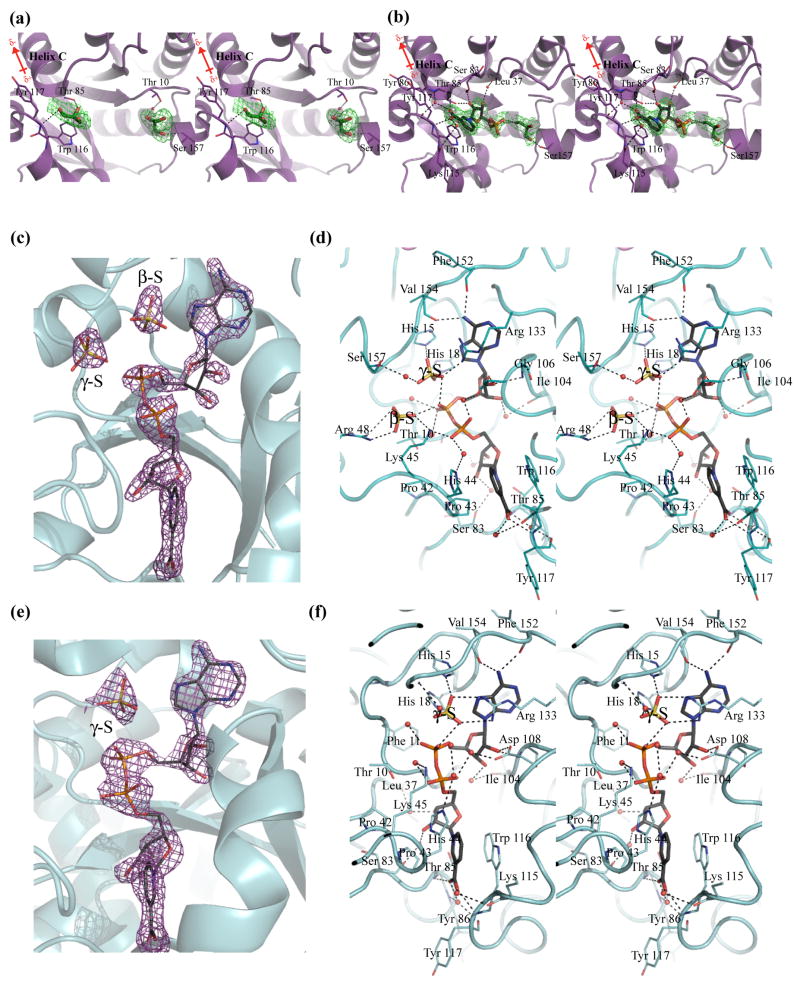

Based on the electron density within the active sites of both monomers, only one NaMN molecule is bound per dimer of NMAT (Figure 7). Within the active site of chain B of the dimer, several features stabilize the bound NaMN substrate, including a series of hydrogen bonds (see below), a pi-stacking interaction between the pyridinic ring of NaMN and the indole ring of Trp116 and neutralization of the carboxylic acid of NaMN by the positive dipole of α-helix C (Figure 7(b)). The nicotinate oxygens also interact with the main chain amides of Thr85 and Tyr117 and with two water molecules within the active site. The presence of two water molecules in these positions is highly conserved in the bacterial NMAT enzymes that have been crystallized to date 12; 16; 20; 22. They are predominantly stabilized by interactions with the amide backbone of Tyr86 and the carbonyl backbone of Lys115 and Tyr117. The hydroxyls of the ribose ring of NaMN hydrogen bond to two additional water molecules which interact with the backbone carbonyls of Ser83 and Leu37 and with the side chain of Thr85. Similar interactions with NaMN or the NaMN moiety of NaAD are observed in the structures of other bacterial NMAT enzymes 12; 16; 20; 22. One NaMN bound per dimer has only been observed in the B. anthracis NaMN complexed structure, thus lending further support for negative cooperativity in substrate binding.

Figure 7. Active sites of B. anthracis NMAT in complex with NaMN and NaAD.

(a) NaMN-binding site of chain A. (b) NaMN-binding site of chain B. The final Fo-Fc omit maps are shown contoured at 3.0σ in green with NaMN and glycerol molecules omitted from the calculations. The bound glycerol molecules are shown as sticks in green and the bound NaMN molecule is shown in dark gray. Water molecules are shown as red spheres, and hydrogen bonds are indicated by broken lines. (c) An Fo-Fc omit map showing the electron density for NaAD, the γ-S, and β-S sulfates in chain B. (d) The NaAD and sulfate ions interactions with NMAT observed in chain B. (e) An Fo-Fc omit map showing the electron density for NaAD and the γ-S sulfate in chain C (identical interactions with NaAD are seen in chain A). Chains B and C make up the functional dimer. (f) The NaAD and the single sulfate ion interactions with NMAT observed in chain C. The final Fo-Fc omit maps are shown contoured at 3.0σ and in purple with NaAD and sulfates omitted from calculations. The bound NaAD molecules are shown in dark gray. Sulfate ions are shown in yellow and water molecules are shown as red spheres. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by broken lines

A strong preference for the nicotinic acid moiety in substrates is observed in other bacterial NMAT’s 16; 23; 24. Since a similar NaMN binding site is observed in B. anthracis NMAT, we hypothesized that B. anthracis NMAT would also show a strong preference for nicotinic acid. Therefore, we tested the ability of NMAT to catalyze the reaction with nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) which has a neutral nicotinamide group. We found that NMAT has little to no activity with NMN, suggesting that NMAT also has a strong preference for the negatively charged carboxylic acid.

The active site of chain B of the NaMN-bound enzyme also contains a single glycerol molecule which is bound in a similar position as a citrate molecule bound within the P. aeruginosa NMAT structure. The glycerol binding site is presumed to occupy the putative ATP-binding site 22. The glycerol molecule is stabilized within the site through interactions with the phosphate of NaMN, the side chain of Ser157, and a water molecule (Figure 7(b)).

In chain A, the electron density reveals two glycerol molecules bound within the active site (Figure 7(a)). One glycerol molecule occupies the NaMN-binding site described above for chain B, where it is hydrogen bonded to the backbone amide of Tyr117 and the side chain of Thr85. The second glycerol molecule is bound in nearly the same position as the glycerol observed in chain B although with slightly different interactions. It is bridged to the side chain of Thr10 of NMAT via a water molecule and it directly interacts with the backbone amide of Ser157. In contrast, the glycerol in chain B interacts directly with the side chain of Ser157.

The presence of glycerol in the active site prompted us to measure the effect of 10% glycerol on the steady-state kinetic parameters. The kinetic parameters of both substrates, ATP and NaMN, were determined in the presence and absence of 10 % glycerol. We found no significant change in the kinetic parameters (Supplemental Table 1). This suggests that 10 % glycerol, which was used for crystallization and flash-cooling, has no influence on the binding of NaMN to the active site of NMAT.

The NaAD binding site

In an attempt to trap the enzyme in the substrate/product complex, crystals were grown in the presence of 2 mM ATP, 2 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM NaMN. NMAT was able to catalyze the reaction under the crystallization conditions leading to the product, NaAD and at least one sulfate molecule, bound in the active-site. The presence of the product is supported by the well-resolved electron density for NaAD (Figure 7(c), (e)), revealing that NMAT is active under the crystallization conditions utilized, and implying that the structure is biologically-relevant.

The structure of the NaAD-bound enzyme provides insight into conformational differences between the substrate-bound and product-bound complexes. The NaAD-bound structure contains three molecules, chains A, B, and C, in the asymmetric unit and belongs to space group C2221 (Table 3). Chains B and C form one dimer, whereas Chain A forms a second dimer with its symmetry-related partner. In chains B and C of the functional dimer, NaAD is bound in a cleft created by β-strands 1 and 4 of the Rossmann fold. The diphosphates are solvent-exposed, while the nicotinate and adenine moieties are buried within the protein (Figure 7(c-f)). NaAD binds in an extended conformation, spanning 18.4 Å from C7 of the nicotinate to C6 of the adenine ring. As noted for other bacterial NMAT enzymes, NaAD release most likely requires large conformational changes within the protein due to the size of the departing product 12; 16; 20

The NaMN-derived moiety of NaAD is bound to NMAT in the same orientation as observed in the NaMN-complexed structure (Figure 7(d), (f)), and the interactions between the product and the enzyme are similar to those observed for other NMAT-NaAD structures 12; 16; 20. However, one large difference between the product-bound B. anthracis NMAT complex and those of other product-bound structures stems from a partially-conserved motif, Pro42-Pro43-His44-Lys45, which, interacts with the pyridinic ring and the NaMN-derived phosphate of NaAD. For other NMAT enzymes, it has been reported that this partially-conserved sequence acts as an arm to recognize the NaMN substrate indicating that it is necessary for NaMN binding to NMAT enzymes 20. However, the B. anthracis NMAT structures reported here demonstrate that these interactions do not occur until NaAD is formed, suggesting that they are less important for NaMN recognition but are essential for NaAD binding. These additional interactions may explain the higher affinity of NMAT for NaAD (KD=3.2 μM) than for NaMN (KD1=382 μM).

In chain B, the NaMN-derived phosphate forms hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Lys45 and with two water molecules that, in turn, interact with the side chains of His44 and Asp108 (Figure 7(d)). The ATP-derived phosphate participates in hydrogen bonding to B. anthracis NMAT via the conserved sequence, Gly8-Gly9-Thr10-Phe11. Three additional water molecules hydrogen bond to the AMP-phosphate and also interact with the backbone amides of Thr10, Phe11, and the side chain of Thr10. Two sulfates found in the active site of chain B also interact with the AMP phosphate. The hydroxyls of the AMP-ribose are hydrogen bonded to the side chain of Asp108 and the backbone amide and carbonyl of Gly106 and Ile104, respectively. The adenine ring is further stabilized by stacking interactions with Arg133 and interactions with the carbonyl backbones of Phe152 and Val154.

One of the sulfate molecules (labeled as γ-S) within the active site is positioned in what would be the γ-phosphate region of the putative ATP-binding site (Figure 7(d)). This sulfate ion is bound via an extensive hydrogen-bonding network contributed by Arg133 and the signature HXGH motif (His15-Tyr16-Gly17-His18). The other sulfate ion (labeled as β-S) is bound in the β-phosphate position of the putative ATP-binding site through hydrogen-bonding interactions with the side chains of Lys45 and Arg48.

From the crystal structure it appears that Arg133 plays an important role in ATP binding and in the stabilization of the negative charge resulting from the phosphates. To test this hypothesis, an Arg133 to Ala133 mutant was made and the kinetic parameters for ATP and NaMN were determined (Supplemental Table 2). The K0.5 values for NaMN (1350 μM) and ATP (570 μM) increased by 64-fold and 4-fold suggesting that the binding of both substrates is affected by Arg133. The kcat of NaMN (34 min−1) and ATP (26 min−1) decreased by 30-fold and 40-fold. The active-site of the R133A mutant could be preventing the catalytically productive binding of the substrates by allowing different binding modes to occur. It has been postulated that NMAT stabilizes the transition state of the reaction without the use of covalent or acid-base catalysis and hence the involvement of specific protein residues for these mechanisms 9; 12. The change in both the K0.5 and kcat may be due to the changes in the electrostatics, orbital geometry, and orientation of the transition state created by the R133A mutant. The positive charge of the arginine aided in the neutralization of the developing negative charge on the PPi leaving group, along with orientating the phosphoryl-oxygen bonds to allow for electron transfer during catalysis. The altered active-site geometry produced upon mutation could prevent NMAT from effectively stabilizing the geometry of the transition state and therefore produced the 30 – 40 fold decrease in catalytic rate 25. Such dramatic alteration in phosphoryl transfer reactions have been observed in arginine kinase and the hammerhead ribozyme 12; 26; 27.

We also investigated the ability of NMAT to utilize various nucleotides as substrates in place of ATP. Deoxyadenosine triphosphate (dATP), ADP, AMP, thymidine triphosphate (TTP), thymidine diphosphate (TDP), guanosine triphosphate (GTP), guanosine diphosphates (GDP), cytidine triphosphate (CTP), cytidine diphosphate (CDP), inosine diphosphate (IDP), uridine triphosphate (UTP), and uridine diphosphate (UDP) were tested as substrates for NMAT (Data not shown). Only CTP and dATP were able to serve as substrates. dATP was able to catalyze the NMAT reaction at 93 % the rate of ATP (considered 100% activity), suggesting that the 3′ hydroxyl is not essential for ATP binding or catalysis. NMAT was able to catalyze the reaction with CTP at only 26 % the activity as compared to ATP. This suggests that NMAT has a strict hydrogen bonding pattern for the triphosphate, which requires the presence of an amine at the C6 position.

In chain C and chain A, the interactions of NMAT with NaAD are essentially identical to those of chain B, with the exception of His44. This residue forms stacking-interactions with the pyridinic ring of NaAD, instead of pointing toward the solvent, and forming a hydrogen bond with the NaMN-phosphate, as observed in chain B (Figure 7(d), (f)). An additional difference between the two monomers is the presence of only one sulfate molecule in the active site of chain C. The sulfate (labeled as γ-S) is analogous to that found in the putative γ-phosphate binding site of chain B, and takes part in near-identical interactions.

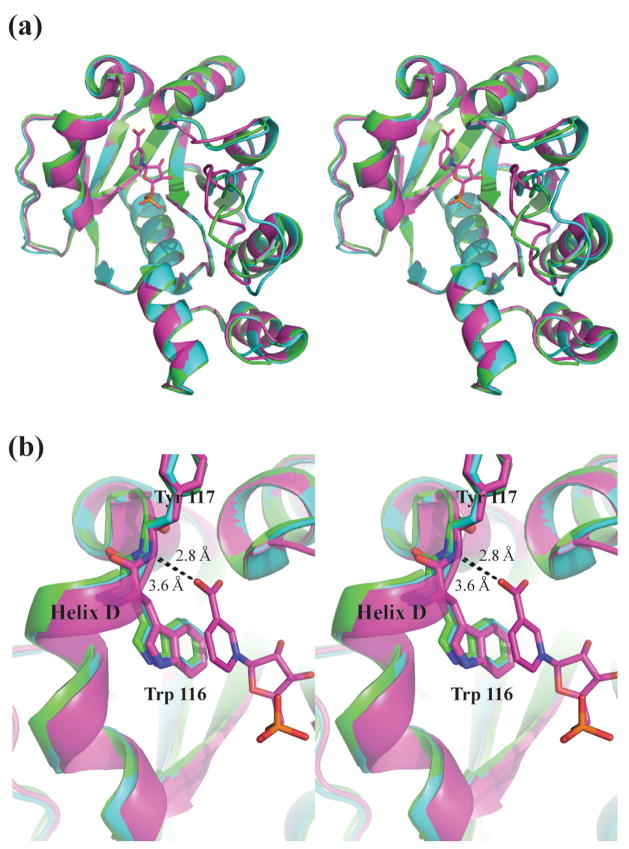

Conformational changes of NMAT upon ligand binding

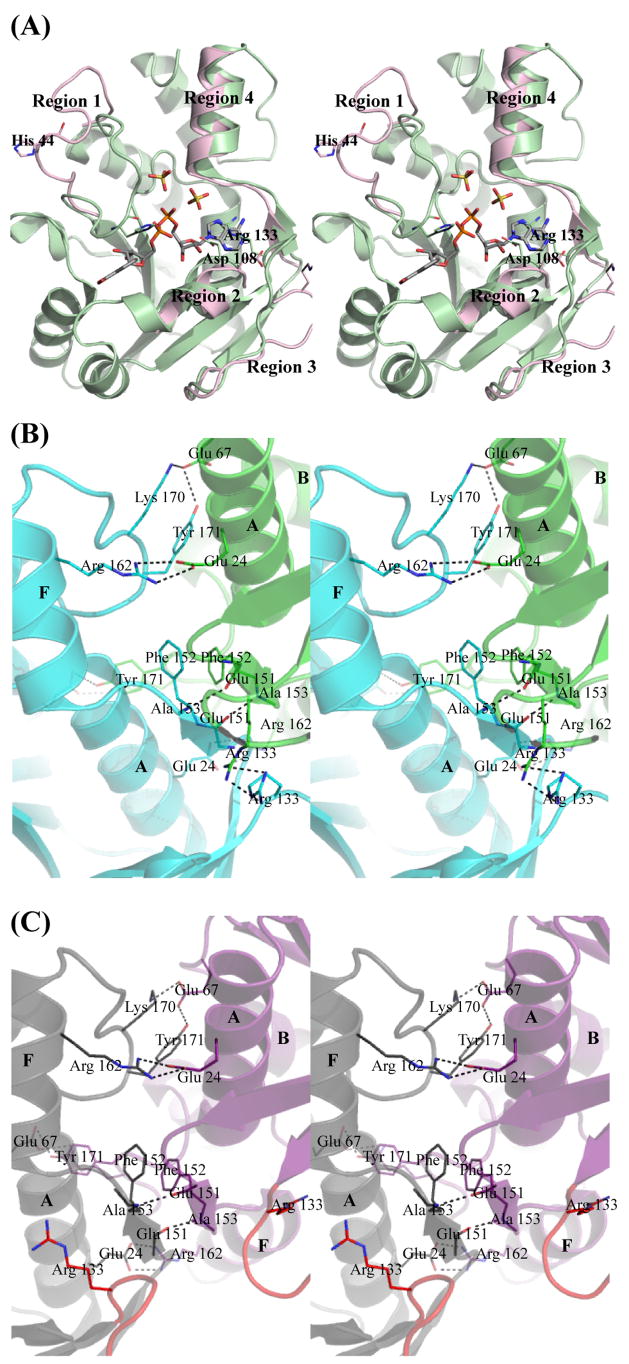

Comparison of the B. anthracis apo-enzyme and NaMN-bound structures to the NaAD-bound structure reveals significant conformational changes upon NaAD formation. Minimal conformational changes are observed globally between the apo-enzyme and the NaMN-bound structures (Overall RMSD = 0.583) (Table 4). The largest conformational changes are observed when the product, NaAD, binds to NMAT, producing overall RMSD’s near 2 Å (Table 4). Four distinct regions of the enzyme are observed to undergo significant conformational change (Figure 8(a)). Region 1 consists of the loop between β-strand 2 and α-helix B which moves 12.8 Å (measured at Cα-His44) to provide additional interactions with the NaMN moiety (Figure 8(a), Region 1). The second region to undergo a conformational change is α-helix D, which shifts 2.5 Å (measured at Cα-Asp108), allowing for interactions with the AMP-ribose (Figure 8(a), Region 2). In the NaAD-bound structure, the loop between β-strands 5 and 6 (Region 3) moves 6.8 Å (measured at Cα-Arg133) relative to its position in the apoenzyme and NaMN-bound structures to allow for the stacking interaction of Arg133 with the adenine moiety (Figure 8(a), Region 3). Another interesting conformational change involves α-helix F, which shifts slightly outward by 1 Å, allowing β-strand 7 and the loop between β-strand 7 and α-helix F to position residues in a more favorable orientation at the dimerization interface (Figure 8(a), Region 4).

Table 4.

Overall RMSD Comparisions. Values are in Ångstroms (Å)

| Apo Structure | NaMN-Bound Structure | NaAD-Bound Structure | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chain A | Chain B | Dimer | Chain A | Chain B | Dimer | Chain A | Chain B | Chain C | Dimer | ||

| Apo Structure | Chain A | X | 0.603 (184) | 0.596 (185) | 0.652 (186) | 1.127 (175) | 0.998 (175) | 1.148 (175) | |||

| Chain B | 0.603 (184) | X | 0.605 (188) | 0.667 (188) | 0.974 (174) | 0.832 (174) | 1.025 (175) | ||||

| Dimer | X | 0.583 (374) | 2.074 (353) | ||||||||

| NaMN-Bound Structure | Chain A | 0.596 (185) | 0.605 (188) | X | 0.772 (186) | 1.134 (175) | 1.00 (175) | 1.094 (174) | |||

| Chain B | 0.652 (186) | 0.667 (188) | 0.772 (186) | X | 1.076 (178) | 0.810 (175) | 0.912 (174) | ||||

| Dimer | 0.583 (374) | X | 2.054 (350) | ||||||||

| NaAD-Bound Structure | Chain A | 1.127 (175) | 0.974 (174) | 1.134 (175) | 1.076 (178) | X | 0.505 (185) | 0.347 (188) | |||

| Chain B | 0.998 (175) | 0.832 (174) | 1.00 (175) | 0.810 (175) | X | 0.499 (185) | |||||

| Chain C | 1.148 (175) | 1.025 (175) | 1.094 (174) | 0.912 (174) | X | ||||||

| Dimer | 2.074 (353) | 2.054 (350) | X | ||||||||

Boxes marked with an X implies there is no RMSD associated with the two chains.

Values in parentheses indicate the number of residues used in the comparision.

Secondary structure matching (SSM) was used in the program Superpose to make pairwise aligments of the NMAT crystal structures.

Figure 8. Conformational changes and dimerization interface of B. anthracis NMAT.

(a) Major conformational changes are labeled as regions 1–4. The NaAD-complex structure is shown in green. Only the regions of conformational change seen in the apoenzyme are shown in pink. (b) Dimerization interface of the apo and NaMN-bound NMAT. Chain A is shown in blue and chain B is shown in green. (c) Dimerization interface of the NaAD-bound NMAT. Chain B is shown in gray and chain C is shown in purple. The loop between β-strands 5 and 6 is shown in red in both chains. α-helices are labeled in letters.

The dimerization interface of the apo-enzyme and NaMN-bound structures are identical, but the interface of the NaAD-bound structure is significantly perturbed as a result of ligand-induced conformational changes. In the apoenzyme and NaMN-bound structures, the dimerization interface is composed of a total surface area of approximately 950 Å2 for chain A and 1,000 Å2 for chain B. The interface is formed by a series of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions between β-strand 7, α-helix A, α-helix F, a loop between α-helix B and β-strand 3, and the C-terminal loop between α-helices F and G (Figure 8(b)). The main hydrophobic interactions result from the pi-stacking of two Phe152 residues, each contributed by one monomer, and from interactions between Arg133 residues of each monomer. The backbone amide of Ala153 of one monomer is hydrogen bonded to the backbone carbonyl of Glu151 of the other monomer. The side chains of Tyr171 and Lys170 from one monomer form hydrogen bonds to the side chain of Glu67 of the other monomer. In addition, the side chain of Arg162 from one monomer forms a salt-bridge interaction with Glu24 from the other monomer. A similar dimerization interface geometry is observed in the structures of NMAT enzymes from other gram-positive bacteria 16; 20.

In contrast, the total surface area of the dimerization interface is reduced to approximately 850 Å2 for each monomer in the NaAD-bound structure. This reduction may be attributed to the loop between β-strands 5 and 6 moving away from the interface and instead participating in NaAD binding (Figure 8(c)). The Arg133 residues from both monomers of the apoenzyme and the NaMN-bound dimer structures interact with one another, whereas in the NaAD-bound structure, these interactions are no longer present and instead each Arg133 interacts with NaAD. All other dimerization interactions observed in both the apoenzyme and the NaMN-bound structures are retained in the NaAD-bound structure (Figure 8(c)).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, B. anthracis NMAT is the first bacterial NMAT enzyme whose kinetic mechanism has been determined. However, various members of the nucleotidyltransferase α/β-phosphodiesterase superfamily have been characterized. These structurally-related proteins catalyze very similar chemical reactions, but their steady-state kinetic mechanisms are diverse 28. For example, sulfate adenylyltransferase exhibits an sequential ordered Bi-Bi mechanism, in which ATP binds first, followed by sulfate, with the release of pyrophosphate and then adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate 29.

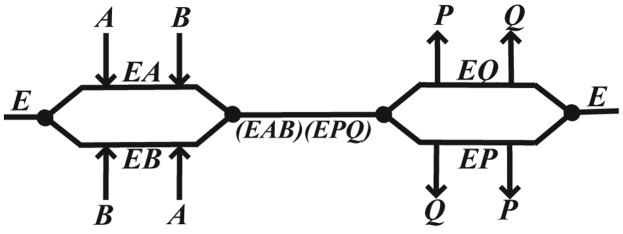

Our kinetic experiments for B. anthracis NMAT reveal a sequential mechanism, based upon the observed changes in the kcat and the slopes of the Lineweaver-Burk plots (Figure 3(a), (b)). In a sequential mechanism (Scheme 1), at low concentrations of the variable substrate (A), the rate-limiting step is binding of A to the enzyme (E) to form the variable substrate-enzyme complex (EA). When the fixed substrate (B) concentration is increased, this will lead to a decrease in the EA complex through B binding to form the transitory complex, EAB. This leads to the equilibrium of the reaction shifting to the right. Therefore, the overall reaction rate is increased and will be observed as a change in the slope of the Lineweaver-Burk plot (Figure 3(a), (b)). At high concentrations of A, a change in kcat is observed in the Lineweaver-Burk plot. A ping-pong mechanism was eliminated as a possibility since a change in the concentration of A would have brought about a change in the intercept, but not the slope of the Lineweaver-Burk plot, and which would therefore produce parallel lines 17.

Scheme 1. Cleland Diagram.

Random bi-bi sequential kinetic mechanism. Abbreviations: E, NMAT; A and B, either NaMN or ATP; P and Q either PPi or NaAD.

We utilized product inhibition studies to differentiate between a sequential ordered mechanism and a random sequential mechanism (Figure 3(c), (d)). The patterns of inhibition arising from a random sequential mechanism will depend on the enzyme’s ability to form the combined substrate-product complexes. Both products, P and Q, will inhibit the enzyme since the binding of either product will prevent at least one substrate from binding. This leads to an inactive enzyme since both substrates, A and B, must be bound for the reaction to proceed (Scheme 1). We have observed that the product, NaAD, acts as a competitive inhibitor against both substrates, NaMN and ATP, which supports a random sequential mechanism. It is unlikely that the reaction mechanism is sequential ordered since NaAD did not act as a noncompetitive or mixed-type inhibitor against either substrate. This kinetic mechanism is similar to that seen for GCT, where the cytidylyltransferase reaction is carried out via a random mechanism, and where there is the presence of negative cooperativity with respect to substrate binding as discussed above 10; 30.

Product inhibition studies with PPi were unsuccessful using either the continuous or discontinuous assay due to interference from the product on each of the assays. Therefore, other experiments were conducted in an attempt to establish the kinetic mechanism. ITC experiments were designed to probe the enzymatic mechanism and binding stoichiometries of B. anthracis NMAT to its ligands. In theory, a random sequential mechanism implies that all substrates and products can bind to free enzyme. Our ITC results indicate that the substrates, NaMN and ATP-Mg2+, and the product, NaAD, bind to free enzyme (Figure 4(a), (b); Table 2). Taken together with the product inhibition studies, these ITC results provide evidence for a random sequential Bi Bi mechanism with the presence of negative cooperativity. This mechanism is further supported by the crystallographic structures of B. anthracis NMAT complexed with NaMN and NaAD since these structures show that both NaMN and NaAD can bind to free enzyme.

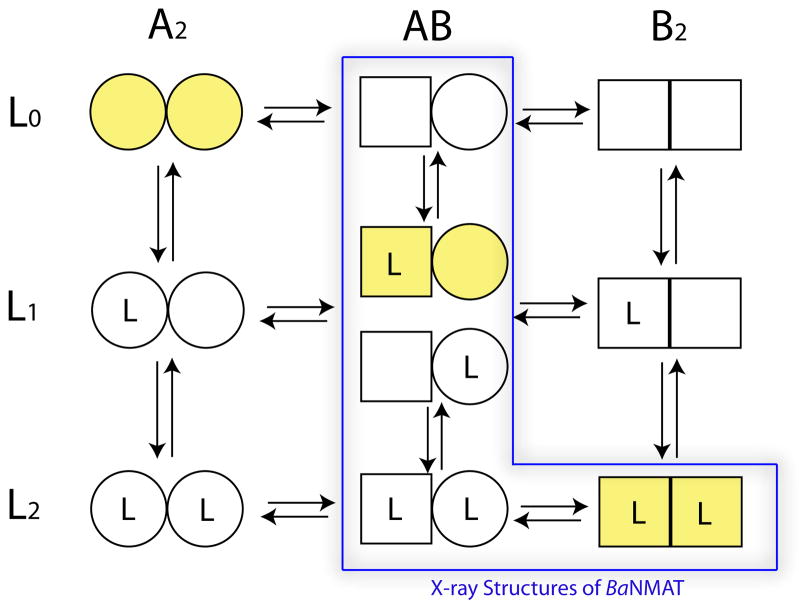

In our kinetic, ITC, and crystallographic studies, we observed negative cooperativity in substrate binding to B. anthracis NMAT. Negative cooperativity causes the binding of each substrate molecule to a protein to decrease the intrinsic affinities of the vacant binding sites. The Koshland-Nemethy-Filmer (KNF) model31, as opposed to the Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) model32, can be used to describe an enzyme with negative cooperativity associated with ligand binding. The KNF model assumes that the apo-protein is symmetric and has binding sites with equal affinities, but as ligands sequentially bind, the protein loses its symmetry and the relative affinities decrease producing negative cooperativity 31; 33. The application of the general sequential model for a dimeric protein, proposed by Koshland and Neet34, to the interaction of substrates and products with NMAT is illustrated in Figure 9. In solution, the molecular species of NMAT, represented by A2, AB, and B2 in Figure 9, exist and are able to form complexes with either one or two ligands (substrates or products) represented by L1 and L2 respectively. The results of the solution-based biochemical and kinetic studies suggest that each these species exists in solution and that the concentration of these species is dependent upon the individual equilibrium constants, the subunit interaction constants, and the concentration of substrates or products.

Figure 9. General sequential model for molecular species in a protein composed of two subunits which undergoes a conformational change under the influence of bound ligand.

The model is adapted from Fig. 5 of Koshland and Neet (1968) and predicts both positive and negative cooperativity. It is assumed that each subunit can exist in two conformations and ligand (L) can bind to either subunit. Ligand L could be substrate, product, or other type of effector molecule. All species shown are potentially possible in the solution or crystalline state. Relative amounts of species will depend on the equilibrium constant of the conversion from A to B (K), the equilibrium constant for binding of L to conformation A (KL′) or B(KL), and strength of subunit interactions (KAA, KAB, KAB),. The simplest sequential model would assume exclusive binding to one conformation and no change in conformation in the absence of bound ligand, i.e. yellow-shaded molecular species. Cooperativity in the sequential model requires preferential binding to one conformation, e.g., B, a shift from A to B conformations with added ligand, and a change in subunit interactions, KAA different from KAB, KAB or both. The values for these equilibrium constants for solution may be different than those for the crystalline form of the protein. The negative cooperativity observed in the kinetic response of B. anthracis NMAT to the binding of substrates suggests it is capable of forming any of the species. The X-ray crystal structures of NMAT represent the AB (apoenzyme), L1AB (NaMN bound) and L2AB, L2B2 (NaAD bound) species of the enzyme. The product-bound, NaAD-NMAT complex, L2AB, is represented by the dimer within the trimeric, asymmetric unit of the unit cell, and the remaining monomer, which composes a symmetrical dimer generated by a 2-fold, crystallographic axis, represents the L2B2 species. The observed conformational species for NMAT in these studies are indicated by the blue box.

The results of the X-ray crystallographic studies suggest that the observed structures in the crystalline state likely represent a subset of the possible protein species present in solution (outlined in blue in Figure 9). The dimeric structure of the NMAT apoenzyme observed in the asymmetric unit would most likely represent the ‘AB’ species since it is not a perfectly symmetrical dimer. The overall RMSD between the two chains of the apoenzyme dimer is 0.603 Å (Table 4) with the exception of the flexible loop region which is slightly higher.

The X-ray structure of NMAT co-crystallized with the substrate NaMN revealed that only one NaMN molecule is bound per dimer in the asymmetric unit. The structure of the NaMN bound dimer most likely represents an L1AB species (Figure 9). The fact that we do not observe either the L2AB or L2B2 species may result from a change in the equilibrium and subunit association constants for the enzyme in the crystalline state, a change which could result from lattice forces. Chain A in the NaMN-bound structure does not contain a bound NaMN molecule and it retains the conformation of the apoenzyme structure (Figure 10). The RMSD between chain A of the NaMN-bound structure and chains A and B of the apoenzyme structure are 0.596 Å and 0.605 Å, respectively (Table 4). In all three of these unliganded chains, α-helix D is shifted outward, causing the side chain of Trp116 and the backbone amide of Try117 to be positioned incorrectly for productive binding (Figure 10). In chain B of the NaMN-bound structure, these residues are positioned correctly to make either a stacking contact or a hydrogen bond with NaMN, leading to productive binding (Figure 10(b)). This productive binding mode appears to only be achieved once NaMN binds to the enzyme. The overall RMSD between chains A (unliganded) and B (liganded with NaMN) is 0.772 Å indicating an overall difference between the two chains of the dimer structure compared to the RMSDs between the unliganded chains (Table 4). Closer inspection of the RMSD for each residue between the two chains of the NaMN-bound dimer reveals RMSD’s of 1 Å – 1.5 Å for the residues involved in formation of α-helix D, supporting the importance of the shift (Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 10. Overlay of Apoenzyme and NaMN-complex of B. anthracis NMAT.

Apoenzyme chain A is shown in green. Chain A and chain B of the NaMN-complex structure is shown in cyan and purple, respectively. (a) Overview of NMAT, showing Chain A of the apoenzyme and chain A of the NaMN-complex structure are in the same conformation, while chain B of the NaMN-complex structure is in a different conformation. (b) Close-up showing the shift in helix D which causes the hydrogen bond formed from the backbone amide of Try117 and the carboxylate of NaMN to either be formed as in chain B of the NaMN-complex or not formed as in chain A of the apoenzyme or the NaMN-complex.

Cocrystalliztion of NMAT with the product NaAD resulted in 3 monomers in the asymmetric unit with each subunit of the ‘trimer’ occupied by one molecule of NaAD. This observation would be consistent with having crystallized both the L2AB and L2B2 species (Figure 9). The first species, L2AB, would represent the non-symmetrical dimer observed in the asymmetric unit. The remaining monomer in the asymmetric unit would represent one monomer of a symmetrical dimer (L2B2) that is generated, via a 2-fold crystallographic axis, from an additional monomer of a symmetry mate. The fact that we observe fully liganded NMAT dimers with NaAD may result from the higher affinity of NaAD for NaMN in solution as well as the higher concentration of NaAD used in the crystallization solutions. These conditions may have driven the equilibrium towards the fully-liganded species despite any changes in the equilibrium or subunit interaction constants of NMAT in the crystalline state.

There are a number of additional protein systems that display negative cooperativity which have been “trapped” in their asymmetric states structurally. For example, four well-studied proteins displaying negative cooperativity as described by the KNF model include: thymidylate synthase, the aspartate chemoreceptor, GCT, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), 10; 33; 35; 36. In the case of thymidylate synthase, binding of the cofactor 5,10-methylene tetrahydrofolate to one monomer causes a conformational change in the second monomer that prevents cofactor binding 35. For the aspartate chemoreceptor, when the first aspartate molecule binds to one monomer of the dimeric receptor, it induces a conformational change that causes the second binding site to become partially closed which decreases substantially the affinity of the second binding for an additional aspartate 36. A series of X-ray crystal structures of the aspartate receptor have been determined that represent a number of the various species represented in Figure 9 37.

GCT, like NMAT, is a member of the nucleotidyltransferase α/β-phosphodiesterase superfamily and utilizes negative cooperativity as a means of regulating its enzymatic activity 10. From NMR studies it was concluded that the allosteric mechanism for negative cooperativity is based on an increase in the energy required for the second subunit to reach the bound state, which is a similar mechanism described for GAPDH 10; 33. Both GAPDH and GCT have been shown to retain their apo conformations in the subunits not containing a bound ligand, providing evidence that the negative cooperativity in these systems is not derived from changes in interactions between subunits that are transmitted to the unoccupied binding sites 10; 31; 33.

To our knowledge, B. anthracis NMAT is the first prokaryotic NMAT enzyme identified with negative cooperativity. NMAT is found at the branch point between the de novo and salvage NAD(P) biosynthetic pathways (Figure 1). The ability of the bacterial cell to regulate the biosynthesis of NAD(P) is essential for cell viability. The negative cooperativity associated with NMAT kinetics could serve as one these regulatory mechanisms, since we have not yet observed kinetic control of NMAT by other effector molecules within the NAD/P biosynthetic pathway. When the bacterial cell is deficient in ATP, the NAD(P) biosynthesis must be slowed to prevent the unbalancing of the NAD(P)/NAD(P)H ratios. The negative cooperativity of NMAT could function to slow the biosynthesis under these circumstances. Our studies support that at low, fixed ATP concentrations, binding of NaMN to one monomer negatively influences the binding of a second NaMN to the other monomer, which therefore decreases the catalytic efficiency. Another possibility, in the case of low concentrations of ATP, may be for the reverse reaction to take place, which would increase the ATP levels within the cell. Our attempts to measure the reversibility of the NMAT reaction reveal that the production of ATP using NMAT is extremely rapid and could therefore lead to a dramatic increase in ATP within the bacterial cell.

Conversely, a signal of energy availability within a cell is a high concentration of ATP, which requires efficient NAD(P) synthesis to sustain anabolic metabolism. At high concentrations of ATP, we observe a decrease in the extent of negative cooperativity of NMAT kinetics with respect to NaMN which at times of high energy availability, would allow for the rapid synthesis of NAD(P). The rate of NAD and NADP utilization by the cell would directly influence the flux through the NMAT reaction. If NAD(P) concentrations buildup within the cell, the production of these cofactors could be rapidly shutdown at the NMAT reaction by a buildup of NaAD which would reverse the flux back to the production of ATP. Product inhibition by NaAD and its tight association with NMAT, in addition to the associated negative cooperativity in the interaction of ATP and NaMN, emphasizes a regulatory role of NMAT in NAD(P) production under high energy availability, i.e. high ATP concentrations, and ATP and NaMN generation under cellular conditions whereby the pools of NAD(P) are in excess.

A related adenylyltransferase, phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase (PPAT) has been shown to be a secondary regulator of the CoA biosynthetic pathway with pantothenate kinase (CoaA) being the primary regulator via feedback regulation 38; 39. Similar to the NaMN-NMAT complex structure, crystal structures of PPAT provide evidence for the extreme form of negative cooperativity, half-of-sites reactivity, which may be functioning as the secondary regulatory role of the CoA biosynthetic pathway 9; 38. NMAT may be functioning in a similar role as that of PPAT, where negative cooperativity is used as the secondary regulation mechanism.

It has been shown that negative cooperativity can function as a regulatory mechanism for human 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase. Negative cooperativity is proposed to participate in the regulation of the pentose phosphate shunt in human erythrocytes via negative cooperative binding of NADP and NADPH 40. In contrast to the prokaryotic NMAT enzymes studied to date, with the exception of B. anthracis NMAT, the archaes have been shown to be regulated by negative cooperativity 41; 42; 43. In addition, human NMAT enzymes are proposed to play an essential role in preventing NAD and ATP depletion during the cellular rescue from DNA damage caused by over activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 44; 45.

In conclusion we have established that NMAT utilizes a random sequential Bi Bi kinetic mechanism in its interaction with substrates and that these interactions involve negative cooperativity. A potential regulatory role for the negative cooperativity associated with B. anthracis NMAT in the NAD(P) biosynthetic pathway is suggested by these results which may help to further our understanding of the regulation of the NAD(P) biosynthetic pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and overexpression of B. anthracis Nicotinate Mononucleotide Adenylyltransferase (NMAT)

The NMAT gene was PCR amplified from the genomic DNA of Bacillus anthracis Sterne strain. The N-terminal primer: 5′-GGA ATT CCA TAT GAG AAA AAT TGG CAT CAT T-3′ and the C-terminal primer: 5′-TAG GGA TCC TCA CGA ACC ATA CAA CCC ATT-3′ were synthesized by Sigma Genosys. The N-terminal primer contains an Nde1 restriction site upstream of the start codon (shown in bold). The C-terminal primer contains a BamHI restriction site downstream from the stop codon (shown in bold). The cycling parameters for the PCR reaction were 94°C for 1 min, and then continued for 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 50°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min. The PCR product was purified using the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega). A pET15b vector containing an N-terminal (His)6-tag, pET11a vector (Novagen), and the PCR product were digested with BamHI and NdeI restriction enzymes and purified via the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). The digested NMAT gene was then ligated into both digested pET15b and pET11a expression vectors and transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue cells. The resulting clones were screened for the presence of inserts by PCR amplification using the above primers. The gene sequences were verified by dideoxy sequencing at the UIC DNA Core facility. The resulting expression plasmids were designated NMAT-pET15b and NMAT-pET11a and were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells for protein overexpression. Both NMAT constructs were overexpressed in the same manner. Single colonies were used to inoculate 10 mL starter cultures that were grown for 8 hr at 37°C. Each starter culture was used to inoculate 1 L of LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin and then grown for 17 hours at 37°C.

Site-directed mutagenesis

The R133A mutant was constructed using the QuikChange™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit from Stratagene. The N-terminal primer: 5′-GGA GTT GCA AGA CCT GGT TAT AAA TTG CGT ACA CCT-3′ and the C-terminal primer: 5′-ATA ACC AGG TCT TGC AAC TCC AAC AAA CGT TAC AAG-3′ were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. The location of the codon that generated the mutation is shown in bold. The cycling parameters for the PCR reaction were 94°C for 3 min, and then continued for 16 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 57°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 14 min. The PCR product was then digested with Dpn1 to remove template DNA and then transformed into supercompetent XL1-Blue E. coli cells. The sited-directed mutation was verified by dideoxy sequencing at the UIC DNA Core facility.

Purification of (His)6-tag NMAT

The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 15 minutes (Sorvall SLC-4000), suspended to 3 mL/g of cell pellet in lysis buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), lysozyme (0.2 mg/mL), and DNase I (0.002 mg/mL). The cells were lysed by sonication and centrifuged at 17,000 rpm for 30 minutes (Sorvall SA-600). The clarified cell lysate was loaded onto a 5 mL HiTrap affinity column (GE Healthcare) charged with Co2+ and equilibrated with equilibration buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole). (His)6-tag NMAT was eluted by a linear imidazole gradient from 0% to 100% elution buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, and 0.5 M imidazole). The fractions containing (His)6-tag NMAT protein were pooled and then exchanged into buffer containing 30 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.25 M NaCl, and 10% glycerol using a Centricon Plus-20 with a molecular weight cut-off of 10 kDa (Millipore). 150 mg of pure protein was obtained per liter of culture. The enzyme was flash frozen for long-term storage at −80°C. The R133A (his)6-tag mutant NMAT was purified in the same manner as described above, yielding 200 mg of pure protein per liter of culture.

Purification of native NMAT

BL21(DE3) cells expressing native NMAT were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 15 minutes (Sorvall SLC-4000), suspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), lysozyme (0.2 mg/mL), and DNase I (0.002 mg/mL)). The cells were lysed by sonication and centrifuged at 17,000 rpm for 30 minutes (Sorvall SA-600). Ammonium sulfate was added to the clarified lysate to 40% (w/v), and the precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation at 17,000 rpm for 30 minutes (Sorvall SA-600). The supernatant was loaded onto a phenyl sepharose 6 FF HS column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 30 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 and 40% ammonium sulfate. The protein was eluted using a decreasing linear salt gradient from 0% to 100% elution buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5). Fractions containing NMAT were pooled and exchanged into Mono Q equilibration buffer containing 30 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 using a Centricon Plus-20 with a molecular weight cut off of 10 kDa (Millipore). The protein was loaded onto an 8 mL Mono Q column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with equilibration buffer and eluted with an increasing salt gradient from 0% to 100% Mono Q elution buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl). Fractions containing NMAT were pooled and exchanged into a buffer containing 30 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol using Centricon Plus-20 devices (Millipore). A final yield of 65 mg of protein per liter of culture was obtained. The native NMAT was flash frozen for long term storage at −80°C.

Oligomeric state determination of (His)6-tag NMAT

The oligomeric state of (His)6-tag NMAT was determined using a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 high-performance, gel filtration column (GE Healthcare). The column was equilibrated with 30 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 and 250 mM NaCl and was calibrated by running a set of protein standards containing the following proteins (molecular weights and retention volumes are in parenthesis): chymotrypsinogen (19.5 kDa, 15.32 mL), ovalbumin (48.2 kDa, 13.51 mL), bovine serum albumin (67 kDa, 12.15 mL), aldolase (158 kDa, 10.79 mL), catalase (232 kDa, 8.75 mL), ferritin (440 kDa, 7.32 mL), and thyroglobin (669 kDa, 6.61 mL). The void volume of the column was calculated from the retention time of a 10 mg/mL sample of blue dextran.

The oligomeric state of (His)6-tag NMAT was determined by running a 50 μL sample of purified recombinant protein at concentrations of 5 mg/mL and 10 mg/mL over the column in triplicate. The elution volume was calculated using the AKTA FPLC software (GE Healthcare). The apparent molecular weight was estimated by comparing the relative mobility (Kav) to the Kav of the standards through a plot of the log of the molecular weights of the standards versus their Kav’s.

NMAT continuous activity assay

A continuous assay to monitor the reaction catalyzed by B. anthracis NMAT in the forward direction was based upon the EnzCheck pyrophosphate assay (Molecular Probes). The increase in absorbance at 360 nm was monitored on a SpectraMax plate reader for the 96-well based assay. A standard 200 μL reaction mixture contained: 50 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.075 U IPP, 0.5 U PNP, 300 μM MESG, pH 7.5, with various concentrations of NaMN and ATP ranging from 1 μM to 1 mM. The reaction was initiated with 25 nM (His)6-tagged or native NMAT. The effects of glycerol on the kinetic parameters of ATP and NaMN were tested using the same standard 200 μL reaction mixture as stated above with the addition of 10 % glycerol. The following effector molecules were tested for their ability to inhibit or activate NMAT at concentrations of 25 μM, 750 μM, and 2 mM: NaAD, L-aspartic acid, quinolic acid, NAD, NADP, PRPP, DHAP and NMN. Each 200 μl contained the standard components except ATP was fixed at 30 μM and NaMN was fixed at 20 μM. NMAT’s nucleotide specificity was tested using the following compounds at a concentration of 500 μM: dATP, ADP, AMP, TTP, TDP, GTP, GDP, CTP, CDP, IDP, UTP, and UDP using a standard 200 μl reaction mixture for the continuous assay, with the concentration of NaMN at 250 μM. The mononucleotide specificity determined using the standard 200 μl reaction mixture, with the concentration of ATP at 500 μM and either 1 mM NaMN or 1 mM NMN.

NMAT discontinuous activity assay

The discontinuous HPLC assay is based upon the assays published by Mehl et al. 23 and Balducci et al. 46. All reactions were carried out in 96-well plates. Each 100 μL reaction consisted of 30 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, various concentrations of ATP and NaMN ranging from 1 μM to 1 mM. The reaction was initiated with the addition of 12.5 nM (His)6-tagged NMAT. Following an incubation time of 3 minutes, the reactions were quenched with the addition of 50 μL of 1.2 M perchloric acid and then neutralized with 50 μL of 1 M potassium carbonate. The 96-well plates were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 30 minutes (Sorvall ST-H750) to pellet the precipitate. The reactants and products were separated by chromatography on a 4.6 × 50 mm 3.5 micron Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 column (Agilent Technologies). A 0.8 mL/min isocratic flow of 96.8% 60 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.0 and 3.2% methanol for 2.5 minutes was used for separation of the reaction components. The absorption of the reactants and products was detected at 254 nm. Under these conditions, NaMN eluted at 0.6 min, ATP at 0.9 min, and NaAD at 1.9 min. The rate of the forward reaction was determined by calculating the amount of NaAD produced per minute based on a standard curve.

The reverse reaction was assayed under similar reactions conditions as stated above, except 30 μM of NaAD and 10 mM of inorganic pyrophosphate served as substrates. The reaction was initiated with the addition of either 10 nM, 25 nM, or 50 nM (His)6-tagged NMAT and 4 different incubation time points were take 0, 30 sec, 1 min, and 5 min. The appearance of ATP was monitored at 254 nm and separated from the substrates and NaMN via the method described above.

Steady-state kinetics of NMAT

The reaction mechanism of (His)6-tagged NMAT was determined by varying one substrate concentration and fixing the concentration of the other substrate. The reaction rates were measured using the aforementioned continuous PPi detection assay. The activity of (His)6-tagged NMAT was monitored at variable concentrations of ATP for a variety of fixed concentrations of NaMN ranging from 10 μM to 1mM. The activity of (His)6-tagged NMAT was also monitored at variable concentrations of NaMN for a variety of fixed concentrations of ATP ranging from 10 μM to 1 mM. The data were analyzed using the Enzyme Kinetics Module within the SigmaPlot 2000 program (Systat Software, Inc.). The resulting Lineweaver-Burk plots established that negative cooperativity is present due to the downward curvature of 1/v with increasing 1/[S]. Therefore, the data were fit to the Hill equation (Eq. 1)

| Eq. 1 |

where Vmax is maximal velocity, S is substrate concentration, nH is the Hill coefficient, and K0.5 is the concentration of substrate that leads to 50% of the Vmax.

The kinetic parameters of native NMAT and the R133A (his)6-tag mutant NMAT were determined under identical conditions and were found to be within error of those of (His)6-tagged NMAT (Supplemental Figure 2, Supplemental Table 2). All further kinetic experiments were conducted using the (His)6-tagged NMAT due to ease of purification.

Product inhibition studies

Product inhibition studies were conducted using NaAD as an inhibitor. For any given assay, one substrate was fixed at a non-saturating concentration and the other substrate concentration was varied between 5 μM and 1 mM. (His)6-tagged NMAT activity was assayed using the continuous activity assay both in the presence and absence of fixed amounts of NaAD ranging from 0–100 μM. For each fixed concentration of NaAD, the data were fit to the Hill equation using the Enzyme Kinetics Module within the SigmaPlot 2000 program (Systat Software, Inc.). The individual Lineweaver-Burk plots were overlaid in SigmaPlot to generate the graphs in Figure 3(c) and 3(d).

ITC experiments

ITC measurements were performed at 25°C on a MicroCal VP-ITC. For all experiments the solution conditions were 30 mM buffer (Tris-HCl or HEPES) at a pH of 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol. Excluding the ATP titration experiment, the both the cell and syringe solutions also contained 25 mM MgCl2. In a typical experiment, 8 μL aliquots of NaMN, ATP, or NaAD were sequentially injected from a 250 μL rotating syringe (300 RPM) into an isothermal sample chamber containing 1.42 mL of protein solution. In all experiments the protein concentration ranged between 170–185 μM, NaMN and ATP concentrations were 20 mM, while the NaAD concentration was 4 mM. The initial delay prior to the first injection was 60 s. The duration of each 8 μL injection was 16 s. with a delay between injections ranging from 250–300s. Each ligand-protein experiment was accompanied by the corresponding control experiment in which equivalent aliquots of the ligand were injected into a solution of buffer alone, except for the NaAD titration where the last 10 injections were used as the heat of dilution. The heat associated with each injection was determined by integration of the area under each peak (Origin software (MicroCal, Inc.)). The heat associated with each ligand-buffer injection was subtracted from the corresponding heat associated with the ligand-protein injection to yield the heat of ligand binding for that injection. The resulting corrected injection heats for the substrates NaMN and ATP were best fit by a model for sequential binding sites and the best fit by a model for one site binding was used for the product, NaAD.

Crystallization of (His)6-NMAT apoenzyme, NaMN-bound and native NaAD-bound NMAT

Crystallization trials were performed by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. Initial conditions for the apoenzyme were identified using the Hampton Research Index Screen, in which crystals were obtained by mixing 2 μL of 10 mg/mL (His)6-tagged NMAT with 2 μL of well solution containing 50% Tacsimate pH 7.0. Thin rod clusters appeared after three days, and crystallization was improved with the addition of 10% glycerol to the well solution and 20 μM CoCl2 to the protein drop. The addition of the 10% glycerol and 20 μM CoCl2 slowed crystal growth, which allowed for larger rods to form. The (His)6-NMAT-NaMN co-crystals were grown under the same conditions as the apoenzyme with the addition of 1mM NaMN to the protein solution. Two Co2+ cations were observed in both the apo and NaMN-bound crystals structures, providing additional crystal contacts.