Abstract

Nuclear translocation is an important step in glucocorticoid receptor (GR) signaling and assays that measure this process allow the identification of nuclear receptor ligands independent of subsequent functional effects. To facilitate the identification of GR-translocation agonists, an enzyme fragment complementation (EFC) cell-based assay was scaled to a 1536-well plate format to evaluate 9,920 compounds using a quantitative high throughput screening (qHTS) strategy where compounds are assayed at multiple concentrations. In contrast to conventional assays of nuclear translocation the qHTS assay described here was enabled on a standard luminescence microplate reader precluding the requirement for imaging methods. The assay uses beta-galactosidase alpha complementation to indirectly detect GR-translocation in CHO-K1 cells [Fung, P., et al. Assay Drug Devel. Technol. 2006, 4(3): 263–272]. 1536-well assay miniaturization included the elimination of a media aspiration step, and the optimized assay displayed a Z′ of 0.55. qHTS yielded EC50 values for all 9,920 compounds and allowed us to retrospectively examine the dataset as a single concentration-based screen to estimate the number of false positives and negatives at typical activity thresholds. For example, at a 9 μM screening concentration the assay showed an accuracy that is comparable to typical cell-based assays as judged by the occurrence of false positives that we determined to be 1.3% or 0.3%, for a 3σ or 6σ threshold, respectively. This corresponds to a confirmation rate of ~30% or ~50%, respectively. The assay was consistent with glucocorticoid pharmacology as scaffolds with close similarity to dexamethasone were identified as active, while, for example, steroids that act as ligands to other nuclear receptors such as the estrogen receptor were found to be inactive.

Keywords: qHTS, HTS, EFC, PubChem, glucocorticoid receptor, nuclear translocation, suspension cells

Introduction

The glucocorticoid receptor (GR, NR3C1) is a member of the nuclear receptor family of ligand-dependent transcription factors. Nuclear receptors have a modular structure consisting of a ligand-binding domain (LBD) and a DNA-binding domain (DBD). Upon binding of ligands, GR translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus.1, 2 The GR-ligand complex within the nucleus binds as a dimer to specific DNA recognition sequences, glucocorticoid response elements, and co-regulator proteins that lead to either enhancement or suppression of gene transcription from a wide variety of glucocorticoid-responsive genes.3 In addition to their important roles in normal physiology and metabolism, glucocorticoids are administered as treatments for a wide variety of allergic, autoimmune, and neoplastic conditions and thus GR has been a valuable target for drug development.4–8

A number of nuclear receptor assay formats have been devised for HTS.9 For enabling the identification of selective GR ligands such assays include radiometric and fluorometric ligand-binding assays using purified GR-LBD10–12, GR translocation assays and GR transcriptional reporter gene assays.13,14 As translocation may be an important intervention point in the regulation of GR function, there is increasing interest in studying GR translocation and developing new assays that are able to monitor translocation in a cellular environment.

In the absence of its ligand, the GR is sequestered to the cytoplasm where it is associated with the heat shock protein Hsp90.15, 16 In the presence of its cognate ligands, GR becomes activated after induction of HDAC6 acetylation of the Hsp90.17–19 Interestingly, a reduction in GR translocation may be responsible for glucocorticoid resistance in a subgroup of asthma patients.20, 21 Thus, analysis of events involved in GR translocation may lead to discovery of non-steroidal small molecules capable of more effectively modulating GR activity, highlighting the importance of cell-based assays and the use of the full-length NHR protein.

Nuclear translocation is an event common to ligands that either enhance or repress gene transcription.2 Therefore, assays that measure translocation enable the identification of both agonists and antagonists in a single assay format. To date, high-content assays have been the method of choice for measuring translocation.22, 23 Immunocytochemical staining is commonly used for constructing nuclear translocation assays. However, such formats are not suitable for high throughout screening due to the multiple reagent additions, cell permeablization and washing steps required. Alternatively, translocation can be monitored by fusing autofluorescent proteins such as GFP to the protein of interest. We recently applied such an assay to measure translocation of GR in a 1536-well assay system using laser-based microplate cytometry to enumerate GFP positive nuclei24. However, concerns are sometimes raised in GFP-based systems due to the need to express sufficient amounts of the GR-GFP fusion protein for efficient imaging, which may in some cases interfere with particular pathways.25

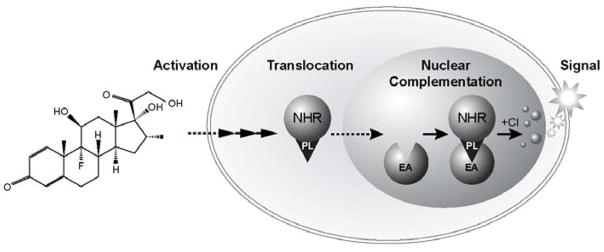

Recently, α-complementation-based assays for nuclear translocation have been described26, 27. A GR translocation assay designed for HTS has been developed by DiscoveRx (Fremont, CA) using enzymatic fragment complementation (EFC) of β-galactosidase, an α-complementation technology used widely for configuring various HTS assays28 (Figure 1). This assay uses β-galactosidase as an indicator of GR-translocation in engineered CHO-K1 cells. The enzyme acceptor (EA) fragment of β-galactosidase resides in the nucleus, as designed through the use of a proprietary set of sequence modifications.29, 30 The small peptide enzyme donor (ED, ProLabel) fragment of β-galactosidase is fused directly to the C-terminus of GR§, and is localized in the cytoplasm in the absence of receptor signaling. Upon binding to a GR ligand, the complex translocates to the nucleus, where intact enzyme activity is reconstituted by complementation. The β-galactosidase activity is then detected via conversion of a chemiluminescent substrate.

Figure 1. EFC Assay Principle for Nuclear Translocation Using Positional Complementation.

The positional complementation assay utilizes differential expression in separate cellular compartments of the EA and ProLabel (PL) components of the β-galactosidase complementation technology. One version of this assay monitors nuclear translocation of targets such as nuclear hormone receptors (NHR) without the need for antibodies, GFP or imaging. In this approach, the EA fragment of β-galactosidase is expressed exclusively in the nucleus in a parental clonal cell line. An NHR protein, such as glucocorticoid receptor, is fused to the small ProLabel peptide and expressed in the cytoplasm. When appropriately stimulated with agonist, the NHR target will translocate to the nucleus, the two fragments of β-galactosidase will complement, and a signal will be generated using a chemiluminescent substrate (Cl) for the β-galactosidase enzyme.

To validate this assay we used a compound collection that included known glucocorticoids. The compound collection was screened using quantitative HTS (qHTS) where compounds are screened at seven to fifteen concentrations.31 We describe here the optimization of this GR-EFC assay to provide a homogenous 1536-well plate assay using freshly prepared cell suspensions and the use of qHTS results to evaluate the accuracy and the sensitivity of this novel assay format.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Two types of Kalypsys plates (San Diego, CA) were used in this study. 1536-well white solid plates were used as assay plates and 1536-well polypropylene clear plates were used as compound plates.

Compound Library

A set of 9,920 compounds were obtained from different sources including Sigma-Aldrich (LOPAC; 1280), Tocris (979), Timtec (280), Preswick (1115), Pharmacopia (3000), NCI (1979), Boston University CMLD (718), University of Pittsburgh CMLD (474), and University of Wisconsin (95). Some of these are the known pharmacologically active compounds which were used to evaluate assay performance. The LOPAC, Tocris, Timtec and Prestwick libraries were prepared in fourteen concentrations as 1:2.236 serial dilutions in DMSO in 384-well plates, and subsequently reformatted into 1536-well plates. The remaining compounds were serially diluted to seven concentrations in 1:5 ratio (for details, see Inglese et al. 2006). The compound archive concentrations in 1536-well plates ranged from 0.3 μM to 10 mM.

Cell culture

Clonally derived CHO-K1 cells stably expressing NLS-enzyme acceptor fragment (EA) of β-galactosidase and GR-enzyme donor (ED) fragment of β-galactosidase (ProLabel fragment fused at C-terminal of GR) were maintained in F-12 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 250 μg/ml hygromycin B, 500 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen) at 37°C under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% air.

EFC detection assay

The GR-translocation was measured by β-galactosidase activity using the PathHunter Detection Kit (DiscoveRx, Fremont, CA). The kit contains β-galactosidase substrate reagents. The 1X working solution consists of 1 part substrate and 19 parts lysis buffer prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol (DiscoveRx, Fremont CA).

Instrumentation

The flying reagent dispenser (FRD, Aurora Discovery, San Diego, CA) was used for reagent dispensing.32 Pintool (Kalypsys, San Diego, CA) was used for compound transfer,33 with pin slot set for 1 to 200 dilution. Final DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) concentration was less than 0.5%. Chemiluminescence signal was measured on a ViewLux (PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA) with measurement time 20s and 4X binning.

HTS assay protocol

The assay protocol is described stepwise in Table 1. CHO-K1 cells were detached with trypsin after reaching 85% confluency. Trypsin-containing media was removed by centrifugation; cells were re-suspended with 1% FBS F12 medium without antibiotics (antibiotics are optional at this stage) and subsequently dispensed at a density of 103 cells/well in 1536-well assay plates. Compounds were added and incubated for 2 hr. at 37°C before 1.25 μL per well of β-galatosidase substrate reagents were added. Data were collected using ViewLux after 60 min incubation at room temperature.

Table 1.

GR-EFC 1536-well plate assay protocol

| Step | Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reagent | 5 μL | GR-CHO-K1 cells, 1000 cells per well |

| 2 | Library Compounds | 23 nL | 46 μM - 0.5 nM dilution series |

| 3 | Controls | 23 nL | 100 nM dexamethasone final concentration |

| 4 | Time | 120 min | 37°C and 5% CO2, |

| 5 | Reagent | 1.25 μL | Substrate buffer |

| 6 | Time | 60 min | RT incubation |

| 7 | Output | 20 s | ViewLux detector; clear filter |

Notes

The line stably expressing NLS-enzyme acceptor fragment (EA) of β-galactosidase and GR-enzyme donor (ED) fragment of β-galactosidase. The cells were maintained with F12 medium in the presence of hygromycin B and G418. Cells added with FRD to 1536-well white solid plates and covered with Kalypsys stainless steel gasket-containing plate lids with gas-exchange holes.

Pin-tool compound transfer was performed directly after cell seeding.

Positive control; Pin-tool transfer

Standard cell culture incubation conditions

Substrate buffer diluted 1:5 in final reaction. Added with FRD.

4x binning

Data analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± SD. The screening results were analyzed using Genedata AG (Waltham, MA). A four parameter Hill equation was fitted to the concentration-response (CR) data by minimizing the residual error between the modeled and observed responses. Outliers were masked if the difference with the modeled Hill equation exceeded the noise in the assay that was calculated from the standard deviation of the activity at the lowest tested compound concentration. Additionally, data from higher concentrations were preferentially masked if doing so allowed the fit of the lower-concentration data to achieve significance as judged by efficacy and R2 requirements. The CR curves were then classified based as belonging to one of four classes based on efficacy (response magnitude), presence of asymptotes, and goodness of fit of the curve to the data (R2).31 These classes were (1) complete response curves containing upper and lower asymptotes, (2) incomplete response curves having an upper asymptote, (3) poorly fit curves to activity present only at the highest tested concentration, and (4) inactive, where activity was below 28.6% (3σ for the present assay).31 To represent the data concentration-response curves were plotted using Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) or OriginPro (OriginLab Corp., Northhampton MA). The Z′ factor, an index for assay quality control,34 was determined by

False positive and false negative prevalence analysis was performed by comparing the titration-based qHTS results with single-concentration (1.8 uM and 9 uM) data derived from the qHTS dataset and applying typical hit-thresholds of either 3σ or 6σ Single concentration hits using either threshold were then compared to the CR curves from the qHTS to determine false positives and false negatives using the following definitions:

| Eq. 1 |

where TP = true positives; Compounds in the hit lists that showed high confidence CR curves in the qHTS (Class 1 and 2; see34). Alternatively, the low confidence CR curves (class 3) can be included in this analysis.

FN = false negatives; high confidence CR curves (Class 1 and 2) in the qHTS that were not found as positives in the hit lists.

| Eq. 2 |

where FP = false positives; compounds in the hit lists that were found to be inactive in the qHTS (Class 4).

TN = true negatives; compounds not found in the hit list that were inactive in the qHTS.

In this manner the so-called “confusion matrix”35, 36 containing the numbers of TP, FP, FN and TN could be fully populated for the 3σ and 6σ hit cutoffs.

Results

Assay optimization

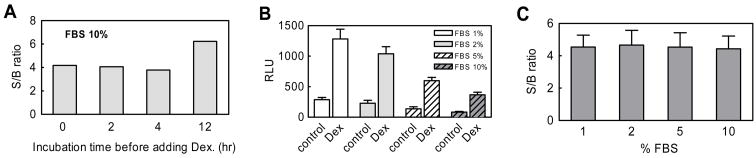

For 1536-well format we have developed a ‘mix-and-read’ protocol and to shorten assay cycle time, we used cell suspensions to perform the EFC-GR screen. To define the optimal assay time, cells were cultured for a variety of times before adding the selective GR agonist, dexamethasone. The signal to background (S/B) ratio was observed to be 4-fold for the assay using freshly prepared cell suspensions. Increases in incubation time showed no clear effect on S/B ratio, although overnight culture of the cells resulted in a 6-fold S/B ratio (Fig. 2A), however this signal improvement would be offset by a significant increase in assay time, a parameter we aimed to minimize.

Figure 2.

Development of a wash-free assay in 1536-well format using fresh suspension cells. (A) Effect of incubation time before dexamethasone (Dex) addition on the S/B ratio. Effect of fetal bovine serum (FBS) on the chemiluminescence signal generated by β-galactosidase (B) and S/B ratio (C). The data was averaged from 64 data points.

In the originally described 384-well format EFC-GR translocation assay, after overnight culture, the medium is replaced with serum-free medium prior to the assay.26 However an important consideration in the adaption of 384-well cell-based assays to a 1536-well format is the removal or minimization of media aspiration steps. To determine the minimum serum concentration acceptable, we performed the assay with concentrations of serum varying from 1–10%. High serum concentrations lead to reduction in the absolute value of the luminescence signal (Fig. 2B), but had no effect on the S/B ratio (Fig. 2C). Given these results and to minimize compound protein binding, 1% FBS was used in the final optimized 1536-well assay used for qHTS.

The effect of cell density on the EFC-GR assay was also examined by measuring the CR curves for the positive control dexamethasone at various cell densities (Fig. 3). Overall, the EC50 values showed no effect at the three tested cell densities (500, 1000 and 2000 per well) using overnight cultures. However, EC50 values from overnight culture were slightly higher than that from freshly suspended cells. In addition, absolute values of luminescence signal from the freshly prepared cell suspension were higher than that from the overnight culture. To balance the cell culture requirements while maintaining a strong luminescence signal output, we chose 1000 cells/well for this protocol. The final optimized assay protocol is shown in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Effect of cell density on dexamethasone-CR curves. (A) For the fresh suspension cells, the EC50 values were 7.9, 15 and 7.8 nM for 0.5k, 1k and 2k per well, respectively. The titrations were plotted by the average of four data points. Dexamethasone was pin-tool transferred to 1536-well plates.

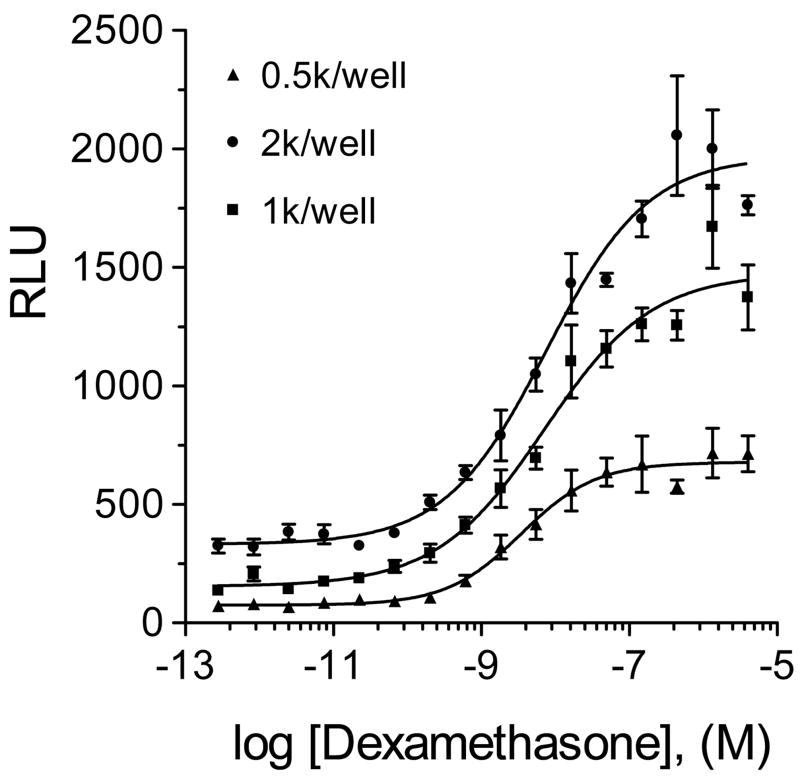

Assay validation and qHTS

qHTS was performed by using the FRD solenoid-bottle-valve dispensers.32 An example of the assay performance is shown in Fig. 4 that was plotted from an assay plate following transfer of DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) alone. For controls, the first two columns contained the positive control dexamethasone at a 0.1 μM final concentration. The S/B was 8.9 and Z′ factor was 0.55, indicating a HTS-compatible assay. For the qHTS each compound was tested at between 7 and 15 concentration points (using a 1:5 or dilution with the highest concentration of 46 μM in the assay) and CR curves were generated for every compound in the 9,920 member validation collection (Table 2). Systematic background patterns were eliminated by using DMSO blanks and lowest concentration plates to detect the assay background signature. In the 100 1536-well plate validation screen, 99 plates gave data suitable for analysis displaying an average robust (median-based) Z′ of 0.43 (Fig. 4) with an average S:B of 8.35.

Figure 4.

1536-well assay and performance (A) Representative screening plate where compound field contains DMSO only. The screen was performed using 1536-white solid bottom plates. For controls, dexamethasone at 0.1 μM was present in column 1 and 2, while column 3 and 4 were DMSO alone and the remaining wells were used for compound testing. The S/B=8.9 and Z′ factor=0.59. All wells contain the same amount of DMSO (30 nL). (B) Robust Z′ analysis of 100 plate validation qHTS.

Table 2.

Analysis of qHTS

| IC50 (uM) | Curve Classification | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 1b | 2a | 2b | 3 | Total | |

| <0.1 | 22 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 |

| >0.1 to 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 9 |

| >1 to 10 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 14 |

| >10 to 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 28 | 35 |

| >100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 56 | 60 |

| Total per classification | 26 | 13 | 4 | 14 | 93 | 150 |

| % library | 0.26% | 0.23% | 0.04% | 0.14% | 0.93% | 1.5% |

To examine the activity of steroid-based compounds in the GR-EFC screen we classified the activity for all 197 steroids present in the compound collection. Of the 197 steroid-like samples that were screened, 47 displayed agonist activity (Class 1 and 2, Appendix 1) and the remaining 150 were inactive (Class 4) A common active scaffold could be identified that described nearly 90% of the actives (41 of the 47 actives; see Figure 5). Inactive scaffolds were more diverse and four common scaffolds could be defined that covered 70% of the inactives (Figure 5).

Appendix 1.

| Entry No. | structure ID | Active Tag | Scaffold Class | qHTS Curve Class | qHTS Max Activity | qHTS Hill Slope | log qEC50 | qEC50 (M) | Supplier Name | Supplier Compound ID | Pub Chem SID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NCGC00016621-01 | T | 1 | 1.1 | −11.23 | 5.90E-12 | Prestwick | CAS-3093-35-4 | 11112527 | ||

| 2 | NCGC00013661-01 | T | 1 | 1.1 | 90.0 | 0.65 | −7.628 | 2.36E-08 | NCI | NSC-53892 | 4253108 |

| 3 | NCGC00015507-01 | T | 1 | 1.1 | 123.7 | 0.55 | −6.498 | 3.18E-07 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-H-4001 | 11111268 |

| 4 | NCGC00016153-01 | T | 1 | 1.1 | 100.0 | 0.62 | −5.952 | 1.12E-06 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-H-2270 | 11112032 |

| 5 | NCGC00016214-01 | T | 1 | 1.2 | 37.8 | 1.35 | −7.782 | 1.65E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-50-22-6 | 11112096 |

| 6 | NCGC00016215-01 | T | 1 | 1.2 | 60.7 | 0.70 | −7.579 | 2.63E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-50-23-7 | 11112097 |

| 7 | NCGC00016476-01 | T | 1 | 1.2 | 74.0 | 0.75 | −6.953 | 1.11E-07 | Prestwick | CAS-514-36-3 | 11112377 |

| 8 | NCGC00015222-01 | T | 1 | 1.2 | 64.0 | 0.77 | −6.747 | 1.79E-07 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-C-2505 | 11110926 |

| 9 | NCGC00015886-01 | T | 1 | 1.2 | 41.2 | 0.59 | −6.363 | 4.34E-07 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-R-0500 | 11111729 |

| 10 | NCGC00016586-01 | T | 1 | 1.3 | 104.7 | 0.69 | −7.725 | 1.88E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-1524-88-5 | 11112491 |

| 11 | NCGC00013220-01 | T | 1 | 2.2 | 100.0 | 0.54 | −6.215 | 6.10E-07 | NCI | NSC-17245 | 4252667 |

| 12 | NCGC00013112-01 | T | 1 | 2.2 | 100.0 | 0.50 | −6.147 | 7.12E-07 | NCI | NSC-10483 | 4252559 |

| 13 | NCGC00015785-01 | T | 1 | 2.2 | 100.0 | 0.38 | −3.652 | 0.000223 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-P-0130 | 11111592 |

| 14 | NCGC00015510-01 | T | 1 | 2.2 | 100.0 | 0.35 | −3.42 | 0.00038 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-H-5752 | 11111272 |

| 15 | NCGC00016616-01 | T | 1 | 2.4 | 100.0 | 0.13 | −5.381 | 4.16E-06 | Prestwick | CAS-2668-66-8 | 11112522 |

| 16 | NCGC00013301-01 | F | 1 | 4 | 1.26 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-23904 | 4252748 | |

| 17 | NCGC00013824-01 | F | 1 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-75541 | 4253271 | ||

| 18 | NCGC00013849-01 | F | 1 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-79103 | 4253296 | ||

| 19 | NCGC00013931-01 | F | 1 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-88915 | 4253378 | ||

| 20 | NCGC00014099-01 | F | 1 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-109131 | 4253546 | ||

| 21 | NCGC00014152-01 | F | 1 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-114792 | 4253599 | ||

| 22 | NCGC00016236-01 | F | 1 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-53-06-5 | 11112118 | ||

| 23 | NCGC00016253-01 | F | 1 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-57-83-0 | 11112137 | ||

| 24 | NCGC00016292-01 | F | 1 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-64-85-7 | 11112177 | ||

| 25 | NCGC00015224-01 | F | 1 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-C-2755 | 11110928 | ||

| 26 | NCGC00015228-01 | F | 1 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-C-3130 | 11110933 | ||

| 27 | NCGC00016604-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | 0.50 | −11.23 | 5.90E-12 | Prestwick | CAS-2135-17-3 | 11112510 | |

| 28 | NCGC00016788-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | −11.23 | 5.90E-12 | Prestwick | CAS-25122-46-7 | 11112699 | ||

| 29 | NCGC00016950-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | −11.23 | 5.90E-12 | Prestwick | CAS-83919-23-7 | 11112866 | ||

| 30 | NCGC00013438-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | 85.0 | 0.79 | −8.636 | 2.31E-09 | NCI | NSC-37641 | 4252885 |

| 31 | NCGC00015165-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | 146.8 | 1.08 | −8.312 | 4.87E-09 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-B-7777 | 11110860 |

| 32 | NCGC00016442-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | 84.0 | 0.63 | −8.086 | 8.21E-09 | Prestwick | CAS-426-13-1 | 11112339 |

| 33 | NCGC00025017-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | 99.4 | 1.27 | −8.047 | 8.97E-09 | Tocris | Tocris-1126 | 11113934 |

| 34 | NCGC00016439-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | 96.5 | 0.89 | −7.634 | 2.33E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-378-44-9 | 11112336 |

| 35 | NCGC00016216-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | 67.7 | 1.02 | −7.53 | 2.95E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-50-24-8 | 11112098 |

| 36 | NCGC00015136-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | 105.1 | 0.67 | −7.278 | 5.27E-08 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-B-0385 | 11110827 |

| 37 | NCGC00015161-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | 156.2 | 0.56 | −7.25 | 5.62E-08 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-B-7005 | 11110856 |

| 38 | NCGC00016822-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | 80.7 | 0.44 | −7.111 | 7.75E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-33564-31-7 | 11112734 |

| 39 | NCGC00016037-01 | T | 2 | 1.1 | 113.5 | 1.03 | −6.563 | 2.73E-07 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-T-6376 | 11111903 |

| 40 | NCGC00016330-01 | T | 2 | 1.2 | 63.5 | 0.98 | −7.457 | 3.49E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-83-43-2 | 11112219 |

| 41 | NCGC00016566-01 | T | 2 | 1.2 | 64.9 | 1.69 | −7.265 | 5.43E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-1177-87-3 | 11112471 |

| 42 | NCGC00016376-01 | T | 2 | 1.2 | 67.5 | 1.15 | −7.082 | 8.27E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-124-94-7 | 11112269 |

| 43 | NCGC00016862-01 | T | 2 | 1.3 | 104.0 | 0.76 | −8.701 | 1.99E-09 | Prestwick | CAS-51333-22-3 | 11112776 |

| 44 | NCGC00016856-01 | T | 2 | 1.3 | 77.5 | 0.52 | −8.507 | 3.11E-09 | Prestwick | CAS-49697-38-3 | 11112770 |

| 45 | NCGC00016983-01 | T | 2 | 1.3 | 97.1 | 0.57 | −8.315 | 4.85E-09 | Prestwick | CAS-542449 | 11112899 |

| 46 | NCGC00016990-01 | T | 2 | 1.3 | 64.5 | 1.18 | −7.909 | 1.23E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-1327543 | 11112906 |

| 47 | NCGC00016433-01 | T | 2 | 1.3 | 80.8 | 0.52 | −7.456 | 3.50E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-338-98-7 | 11112330 |

| 48 | NCGC00016824-01 | T | 2 | 1.4 | 53.9 | 0.52 | −8.69 | 2.04E-09 | Prestwick | CAS-34097-16-0 | 11112736 |

| 49 | NCGC00016926-01 | T | 2 | 1.4 | 30.2 | 0.96 | −8.025 | 9.44E-09 | Prestwick | CAS-73771-04-7 | 11112841 |

| 50 | NCGC00016436-01 | T | 2 | 1.4 | 47.0 | - | −7.893 | 1.28E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-356-12-7 | 11112333 |

| 51 | NCGC00016984-01 | T | 2 | 2.1 | 100.0 | 0.34 | −6.097 | 8.01E-07 | Prestwick | CAS-667634-13-2 | 11112900 |

| 52 | NCGC00013947-01 | T | 2 | 2.1 | 200.0 | 1.30 | −5.5 | 3.16E-06 | NCI | NSC-90616 | 4253394 |

| 53 | NCGC00025343-01 | T | Misc | 1.1 | −11.23 | 5.90E-12 | Tocris | Tocris-2007 | 11114264 | ||

| 54 | NCGC00016943-01 | T | Misc | 1.3 | 115.3 | 1.50 | −9.43 | 3.72E-10 | Prestwick | CAS-80474-14-2 | 11112859 |

| 55 | NCGC00015700-01 | T | Misc | 1.4 | 25.5 | 2.07 | −8.59 | 2.57E-09 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-M-8046 | 11111492 |

| 56 | NCGC00016516-01 | T | Misc | 1.4 | 47.2 | 0.49 | −7.254 | 5.57E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-595-33-5 | 11112421 |

| 57 | NCGC00013946-01 | T | Misc | 2.1 | 200.0 | 1.36 | −5.133 | 7.37E-06 | NCI | NSC-90615 | 4253393 |

| 58 | NCGC00025179-01 | T | Misc | 2.4 | 100.0 | 2.34 | −4.408 | 3.91E-05 | Tocris | Tocris-1479 | 11114100 |

| 59 | NCGC00013010-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-1614 | 4252457 | ||

| 60 | NCGC00013092-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-8797 | 4252539 | ||

| 61 | NCGC00013426-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-36819 | 4252873 | ||

| 62 | NCGC00013541-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-45236 | 4252988 | ||

| 63 | NCGC00013657-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-53396 | 4253104 | ||

| 64 | NCGC00013708-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-59276 | 4253155 | ||

| 65 | NCGC00013713-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-59620 | 4253160 | ||

| 66 | NCGC00013740-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-63558 | 4253187 | ||

| 67 | NCGC00013804-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-73109 | 4253251 | ||

| 68 | NCGC00013865-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-82802 | 4253312 | ||

| 69 | NCGC00013974-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-93241 | 4253421 | ||

| 70 | NCGC00014098-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-109128 | 4253545 | ||

| 71 | NCGC00014902-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-407807 | 4254349 | ||

| 72 | NCGC00014987-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-683770 | 4254434 | ||

| 73 | NCGC00016238-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-53-41-8 | 11112120 | ||

| 74 | NCGC00016238-02 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-53-42-9 | 11112121 | ||

| 75 | NCGC00016238-03 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-481-29-8 | 11112122 | ||

| 76 | NCGC00016295-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-66-28-4 | 11112183 | ||

| 77 | NCGC00016319-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-77-59-8 | 11112208 | ||

| 78 | NCGC00016387-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-128-13-2 | 11112280 | ||

| 79 | NCGC00016387-02 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-474-25-9 | 11112281 | ||

| 80 | NCGC00016406-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-143-62-4 | 11112300 | ||

| 81 | NCGC00016445-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-434-13-9 | 11112342 | ||

| 82 | NCGC00016448-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-467-55-0 | 11112345 | ||

| 83 | NCGC00016452-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-475-31-0 | 11112349 | ||

| 84 | NCGC00016524-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-630-64-8 | 11112429 | ||

| 85 | NCGC00016591-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-1672-46-4 | 11112497 | ||

| 86 | NCGC00016716-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-15500-66-0 | 11112624 | ||

| 87 | NCGC00016782-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-23930-19-0 | 11112692 | ||

| 88 | NCGC00016783-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-23930-37-2 | 11112693 | ||

| 89 | NCGC00017076-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-11018-89-6 | 11112992 | ||

| 90 | NCGC00015090-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-A-7755 | 11110776 | ||

| 91 | NCGC00015112-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-A-9755 | 11110802 | ||

| 92 | NCGC00015804-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-P-1918 | 11111617 | ||

| 93 | NCGC00015805-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-P-2016 | 11111618 | ||

| 94 | NCGC00015820-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-P-5052 | 11111636 | ||

| 95 | NCGC00015853-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-P-8887 | 11111682 | ||

| 96 | NCGC00016061-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-T-9034 | 11111930 | ||

| 97 | NCGC00017282-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Timtec | TNP00197 | 11113200 | ||

| 98 | NCGC00017309-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Timtec | TNP00235 | 11113227 | ||

| 99 | NCGC00024736-01 | F | 3 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Tocris | Tocris-0693 | 11113650 | ||

| 100 | NCGC00013034-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-3354 | 4252481 | ||

| 101 | NCGC00013235-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-18312 | 4252682 | ||

| 102 | NCGC00013236-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-18320 | 4252683 | ||

| 103 | NCGC00013333-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-26645 | 4252780 | ||

| 104 | NCGC00013908-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-86467 | 4253355 | ||

| 105 | NCGC00014013-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-97845 | 4253460 | ||

| 106 | NCGC00014107-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-109509 | 4253554 | ||

| 107 | NCGC00014125-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-112737 | 4253572 | ||

| 108 | NCGC00017797-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | BUCMLD | BUCMLD-JRG-1-179 | |||

| 109 | NCGC00016217-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-50-27-1 | 11112099 | ||

| 110 | NCGC00016218-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-50-28-2 | 11112100 | ||

| 111 | NCGC00016237-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-53-16-7 | 11112119 | ||

| 112 | NCGC00016310-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-72-33-3 | 11112199 | ||

| 113 | NCGC00016682-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-7280-37-7 | 11112590 | ||

| 114 | NCGC00015422-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-E-8875 | 11111161 | ||

| 115 | NCGC00015423-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-E-9750 | 11111162 | ||

| 116 | NCGC00015690-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-M-6383 | 11111479 | ||

| 117 | NCGC00016078-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-U-6756 | 11111950 | ||

| 118 | NCGC00024964-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Tocris | Tocris-1047 | 11113880 | ||

| 119 | NCGC00025091-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Tocris | Tocris-1268 | 11114009 | ||

| 120 | NCGC00025300-01 | F | 4 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Tocris | Tocris-1807 | 11114221 | ||

| 121 | NCGC00016444-01 | F | 5 | 4 | 15.2 | 0.97 | −7.266 | 5.43E-08 | Prestwick | CAS-434-03-7 | 11112341 |

| 122 | NCGC00013637-01 | F | 5 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-51182 | 4253084 | ||

| 123 | NCGC00013978-01 | F | 5 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-93354 | 4253425 | ||

| 124 | NCGC00013979-01 | F | 5 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-93355 | 4253426 | ||

| 125 | NCGC00016231-01 | F | 5 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-52-01-7 | 11112113 | ||

| 126 | NCGC00016254-01 | F | 5 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-57-85-2 | 11112138 | ||

| 127 | NCGC00016440-01 | F | 5 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-382-45-6 | 11112337 | ||

| 128 | NCGC00015070-01 | F | 5 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-A-5791 | 11110752 | ||

| 129 | NCGC00015109-01 | F | 5 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-A-9630 | 11110799 | ||

| 130 | NCGC00015474-01 | F | 5 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-G-5168 | 11111228 | ||

| 131 | NCGC00015948-01 | F | 5 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-S-3378 | 11111798 | ||

| 132 | NCGC00025253-01 | F | 5 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Tocris | Tocris-1672 | 11114174 | ||

| 133 | NCGC00013542-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-45238 | 4252989 | ||

| 134 | NCGC00013601-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-48630 | 4253048 | ||

| 135 | NCGC00013669-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-54340 | 4253116 | ||

| 136 | NCGC00013726-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-62349 | 4253173 | ||

| 137 | NCGC00013777-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-69298 | 4253224 | ||

| 138 | NCGC00013779-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-69540 | 4253226 | ||

| 139 | NCGC00013830-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-76026 | 4253277 | ||

| 140 | NCGC00013866-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-82803 | 4253313 | ||

| 141 | NCGC00014002-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-96021 | 4253449 | ||

| 142 | NCGC00014519-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-179187 | 4253966 | ||

| 143 | NCGC00016331-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-83-46-5 | 11112220 | ||

| 144 | NCGC00016381-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-126-17-0 | 11112274 | ||

| 145 | NCGC00016409-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-145-13-1 | 11112303 | ||

| 146 | NCGC00016502-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-546-06-5 | 11112407 | ||

| 147 | NCGC00016544-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-853-23-6 | 11112449 | ||

| 148 | NCGC00015341-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-D-4000 | 11111068 | ||

| 149 | NCGC00016143-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-D-5297 | 11112022 | ||

| 150 | NCGC00016184-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-P-162 | 11112065 | ||

| 151 | NCGC00017170-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Timtec | TNP00027 | 11113086 | ||

| 152 | NCGC00025241-01 | F | 6 | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Tocris | Tocris-1638 | 11114162 | ||

| 153 | NCGC00016884-01 | F | Misc | 4 | 15.6 | 0.57 | −6.634 | 2.32E-07 | Prestwick | CAS-58652-20-3 | 11112799 |

| 154 | NCGC00013099-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-9746 | 4252546 | ||

| 155 | NCGC00013199-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-15520 | 4252646 | ||

| 156 | NCGC00013292-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-23159 | 4252739 | ||

| 157 | NCGC00013302-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-23922 | 4252749 | ||

| 158 | NCGC00013585-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-48010 | 4253032 | ||

| 159 | NCGC00013734-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-62791 | 4253181 | ||

| 160 | NCGC00013793-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-72254 | 4253240 | ||

| 161 | NCGC00013902-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-86008 | 4253349 | ||

| 162 | NCGC00013920-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-88135 | 4253367 | ||

| 163 | NCGC00014231-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-121137 | 4253678 | ||

| 164 | NCGC00014911-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −3.035 | 0.000922 | NCI | NSC-521777 | 4254358 | ||

| 165 | NCGC00016233-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-52-76-6 | 11112115 | ||

| 166 | NCGC00016235-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-53-03-2 | 11112117 | ||

| 167 | NCGC00016303-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-68-22-4 | 11112191 | ||

| 168 | NCGC00016304-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-68-23-5 | 11112192 | ||

| 169 | NCGC00016318-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-77-52-1 | 11112207 | ||

| 170 | NCGC00016413-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-152-62-5 | 11112307 | ||

| 171 | NCGC00016417-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-297-76-7 | 11112312 | ||

| 172 | NCGC00016443-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-427-51-0 | 11112340 | ||

| 173 | NCGC00016447-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-466-06-8 | 11112344 | ||

| 174 | NCGC00016449-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-472-15-1 | 11112346 | ||

| 175 | NCGC00016450-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-473-98-3 | 11112347 | ||

| 176 | NCGC00016451-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-474-86-2 | 11112348 | ||

| 177 | NCGC00016540-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-797-63-7 | 11112445 | ||

| 178 | NCGC00016609-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-2363-58-8 | 11112515 | ||

| 179 | NCGC00016726-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-17230-88-5 | 11112635 | ||

| 180 | NCGC00016952-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-84371-65-3 | 11112868 | ||

| 181 | NCGC00017016-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-81-23-2 | 11112932 | ||

| 182 | NCGC00017030-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-751-94-0 | 11112946 | ||

| 183 | NCGC00017073-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-7421-40-1 | 11112989 | ||

| 184 | NCGC00017146-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.686 | 0.002061 | Prestwick | CAS-102731 | 11113062 | ||

| 185 | NCGC00015230-01 | F | Misc | 4 | 40.0 | 0.28 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-C-3412 | 11110935 |

| 186 | NCGC00015375-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-D-8399 | 11111105 | ||

| 187 | NCGC00015377-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-D-8690 | 11111107 | ||

| 188 | NCGC00016076-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-U-5882 | 11111948 | ||

| 189 | NCGC00016090-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-W-104 | 11111962 | ||

| 190 | NCGC00016148-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | SigmaAldrich | Lopac-F-0881 | 11112027 | ||

| 191 | NCGC00017165-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Timtec | TNP00020 | 11113081 | ||

| 192 | NCGC00017222-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Timtec | TNP00102 | 11113139 | ||

| 193 | NCGC00017223-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Timtec | TNP00103 | 11113140 | ||

| 194 | NCGC00017244-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Timtec | TNP00130 | 11113161 | ||

| 195 | NCGC00017307-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Timtec | TNP00233 | 11113225 | ||

| 196 | NCGC00017359-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Timtec | TNP00303 | 11113278 | ||

| 197 | NCGC00024732-01 | F | Misc | 4 | −2.336 | 0.004608 | Tocris | Tocris-0687 | 11113646 |

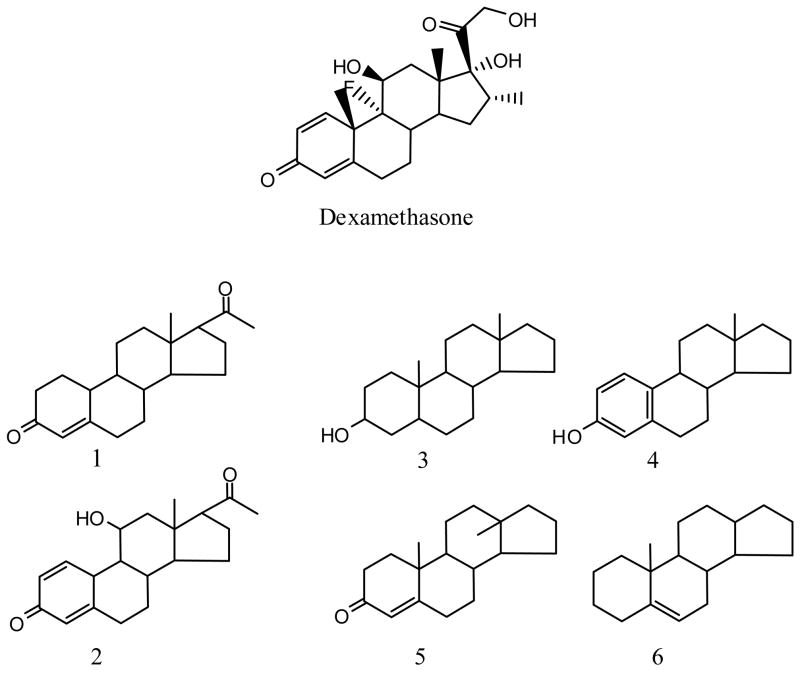

Figure 5.

Dexamethasone control, active and inactive steroid-based scaffolds identified in the qHTS. The active scaffold (1 and 2) covers all 41 of the 47 actives identified. Also shown are representative inactive scaffolds (3–6) that cover 105 of the 150 inactive steroidal compounds.

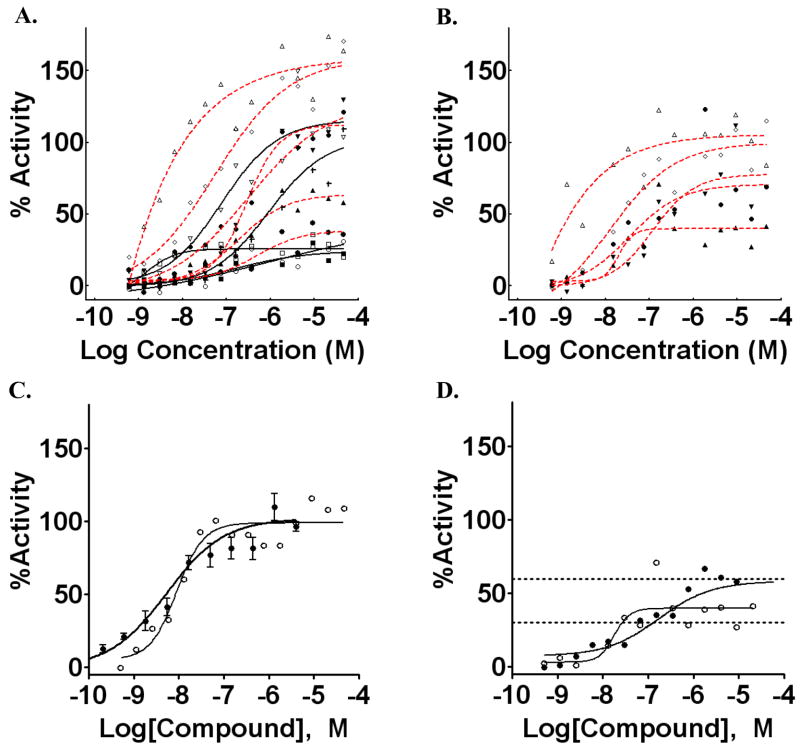

Representative Class 1 curves corresponding to compounds annotated as glucocorticoids in bioactive collections such as LOPAC showed EC50 values < 100 nM for many, and all were < 1 uM (Figure 5). However, while all active steroids showed potent EC50 values (Class 1) large efficacy differences were observed for these in the qHTS. For example, the GR antagonist mifepristone, was present within the LOPAC library and displayed an EC50 of 2.2 nM with an efficacy of approximately 30%. As well, 17α-hydroprogesterone showed an EC50 of 730 nM and increased the luminescence signal only by approximately 30%. Additionally, some compounds were assayed more than once in the qHTS as samples were present from two different vendors (e.g. Prestwick and LOPAC). We noted that such inter-vendor duplicates often showed lower efficacy in the Prestwick library than samples in the LOPAC library (Figure 6a and b, dashed lines). However, the potency was measured at < 100 nM and therefore the qHTS approach identified these as Class 1 CR curves, although the response magnitude varied. The positive control dexamethasone was present in the Tocris library and showed a response that was in good agreement with the validation data for this assay (Figure 6c). Additionally, steroids that act as ligands to other nuclear receptors such as the estrogen receptor were found to be inactive (e.g. Class 4; Appendix 1).

Figure 6.

Titration curves generated for representative glucocorticoids. A) Representative glucocorticoids from the LOPAC collection. □, mifepristone; △, budesonide; upside-down open triangle, beclomethasone; ◇, betamethasone, ○, 17α-progesterone; ■, cyproterone acetate; ▲, corticosterone;▼;, triamcnolone; filled diamond, hydrocortisone, *, 11-deoxycortisol, +, hydrocortisone 21-hemisuccinate. Compounds that were also present in the Prestwick collection are shown with red-dashed fits. B) CR curve data for compounds in the Prestwick collection. Symbols are as in A. C) CR curves for dexamethasone from the validation (●) and the qHTS (○). D) Example CR curves for corticosterone from LOPAC (●) and Prestwick (○). Plots were made by GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA).

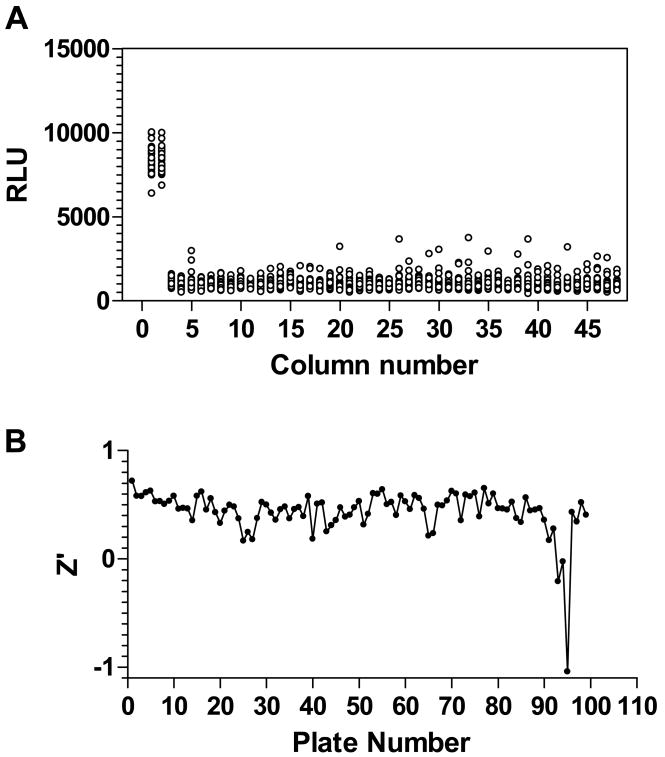

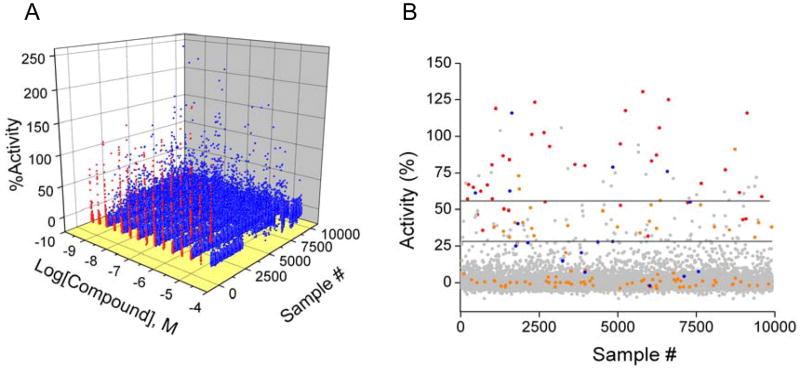

Large scale HTS is most commonly performed using a single compound concentration. Therefore, to evaluate the performance of the assay with respect to a single screening concentration, we conducted a retrospective analysis of the qHTS data (Figure 7a) by examining single concentration datasets from the titration series in isolation (Table 3). A representation of the 9 uM screening concentration is shown in Figure 7b. To perform the analysis we chose to compare positives above either 3σ or 6σ threshold values and asked how many of these compounds were associated with either Class 1 and 2, or Class 1 – 3 CR curves. In comparison to high confidence CR curves (Classes 1 and 2), the percentage of false positives was found to be approximately 1.3% using a 3σ threshold and approximately 0.3% using a 6σ threshold at either a 9 or 1.8 uM screening concentration. This indicates an accuracy of 98.7% for determining a true negative. However given the generally large size of compound libraries (e.g., 9,920 screened in this study), and the fact that the majority of compounds are inactive, even a false positive rate as low as 1% can result in a relatively large number of ‘hits’. Therefore the confirmation of hits is greatly affected by small percentages of false positives. For example, for the assay evaluated here this leads to simulated confirmation rates of approximately 26% or 54% at a 3σ or 6σ threshold, respectively. Therefore for a library of 10K in size we would expect ~130 false positives (i.e., 98.7% accuracy). Note that the fraction of false positives does not depend on screening concentration as expected for stochastic events. Inclusion of the lower confidence CR curves (Class 3) results in a slight reduction in false positives at the 9 uM screening concentration (Table 3). Overall, the assay accuracy observed here is in agreement with typical cell-based assays.37

Figure 7.

qHTS and traditional HTS. A) A 3D scatter plot of qHTS data lacking (blue) or showing (red) concentration-response relationships for all 9,920 samples screened. B) A scatter plot of the 9 uM data with the data colored by the curve class as follows, Class 1 (red), Class 2 (blue), Class 3 (orange), and Class 4 inactive (grey). The thresholds for three and six SD are indicated as black lines.

Table 3.

Summary the retrospective analysis of the qHTS

| 9.2 uM | Threshold | TP | FP | FN | TN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1–2 | 3 σ | 50 | 129 | 7 | 9,735 |

| 6 σ | 38 | 31 | 19 | 9,833 | |

| Class 1–3 | 3 σ | 76 | 103 | NA | 9,668 |

| 6 σ | 45 | 24 | NA | 9,747 | |

| 1.8 uM | Threshold | TP | FP | FN | TN |

| Class 1–2 | 3 σ | 40 | 131 | NA | 9,733 |

| 6 σ | 31 | 27 | NA | 9,837 |

TP, true positive; FP, false positive; FN, false negative; TN, true negative. NA, not applicable. Class 3 CR curves are relevant for this analysis when the 1.8 uM or 9 uM was the highest tested concentration as these curves are fit to a single point. However, all libraries were screened at a higher concentration then 1.8 uM and some were screened at higher than 9 uM and therefore the false negative numbers are found to be inflated when including this curve class. Therefore, for calculation of false negatives we only report the numbers using the high confidence curve classes. Also, note for this reason the TP and FP numbers are the same using Class 1–3 curve class as the comparison set for the 1.8 uM dataset.

As mentioned above many known glucocorticoids were identified using the qHTS approach despite large differences in efficacy between compounds and samples prepared by different vendors. However, to evaluate the sensitivity of the assay using the more common single-concentration-based HTS approach we examined the number of false negative glucocorticoids at two concentrations, 1.8 and 9 uM. This retrospective analysis is possible because of the comprehensive compound concentration range (0.5 nM to 46 uM; Table 1) coverage by qHTS. Using a 3σ threshold we found the false negative rate to be approximately 12% but this increased to 33% when a 6σ threshold was used. One example of how true positives compounds can be missed using threshold values in HTS is illustrated in Figure 6d. Here a glucocorticoid from the Prestwick library shows low efficacy but high potency as determined by qHTS-derived CR curve. However the variation in the assay signal at the 9 uM point caused this data point to fall below the 3σ threshold. Meanwhile, the same compound from the LOPAC library is identified at 3σ but not at 6σ, again largely due to compound efficacy <100% of control values.

Discussion

The regulation of protein localization within cells is one of the fundamental mechanisms operating in signal transduction pathways. The application of EFC to measure GR nuclear localization yields an assay that allows monitoring protein translocation without the use of imaging microscopy technology. We desired to validate this assay in a 1536-well system and were able to optimize the assay using addition-only protocols that enabled a low volume assay with significant improvements in throughput.

The main advantage of using suspension cells is to reduce assay time. Here the use of suspension cells gives a sufficient assay window to perform the GR-EFC assay using the protocol in Table 1. In addition, using suspension cells can reduce the assay cycle time by more than half, lowering the possibility of bacterial contamination that can occur during overnight culture. This was especially important for assay formats using antibiotic-free medium. As well, the use of suspension cells allowed for improved control of the cell density (cells/well) as the cells can be counted just prior to the assay. The optimized 1536-well GR-EFC assay showed good performance with a Z′ score of 0.55. Comparison to a single concentration-based HTS showed that this cell-based assay possessed good accuracy with a false positive rate <1.4%.

The activity of the glucocorticoids in the GR-EFC assay supported the assay’s biological relevance. While known GR ligands were detected with EC50 values in the nM range, compounds selective to other steroid receptors such as the estrogen receptor were inactive. Although literature values do not report detailed information on EC50s for all the glucocorticoids screened here, we were able to compare IC50 values from binding studies with EC50 values from our current GR translocation assay in some cases. In the binding studies cited here, IC50 values were determined as the concentration of compound displacing 50% of [3H]-dexamethasone from specific GR binding. For example, EC50 values for dexamethasone, prednisolone and betamethasone in the current GR assay were all in agreement with the IC50 values found reported from previous studies.38, 39, 40 Specifically, the IC50 for dexamethasone in a binding study was reported at 9.5 nM,38 compared to an EC50 value of 6 nM in the current study. Although the glucocorticoids showed potent EC50 values we noted a wide range of efficacy values (Figure 6 and Table 4). The qHTS approach improved the sensitivity of the assay such that low efficacy compounds that would be missed (i.e., false negative) at a single concentration using typical threshold cutoffs could be easily identified using the qHTS CR curves. Potent but low efficacy activities associated with steroids were also observed in a qHTS against a cell-based assay for IκBα stabilization (also see PubChem AID: 445).41

Table 4.

EC50 values from representing compounds

| EC50 (μM) (GR-EFC assay) | IC50/Kd (μM) [3H]dex binding assay | |

|---|---|---|

| Dexamethasone | 0.0060 | 0.0095 38 |

| Betamethasone | 0.057 | 0.025 38 |

| 17α-hydroxyprogesterone | 2.87 | n/a |

| Corticosterone | 0.036 | 0.048 39 |

| Predinisolone | 0.066 | 0.10 38 |

| Hydrocortisone | 1.52 | n/a |

| Budesonide | 0.005 | n/a |

| Mifepristone* | 0.0022, 0.0013** | 0.0015 40 |

| Fluticasone propionate | 0.0061 | n/a |

IC50/Kd Values were derived from GR binding study using GR-rich cell extract.

Mifepristone show only a 30% effect compared to Dexamethasone in this assay;

independent re-test value with 25% efficacy

Our results for mifepristone illustrate the potential for this kind of translocation assay to identify low efficacy actives. Mifepristone has been classified as an antagonist for the progesterone nuclear receptor and GR42, but also observed to have GR agonist activity in some types of cells43. In the present study, the EC50 for mifepristone was 2.2 nM, but it produced only a 28% maximal increase in translocation activity which would act to antagonize the action of GR agonists such as dexamethasone. The reported reduction in dexamethasone-mediated GR translocation by mifepristone is consistent with findings that mifepristone does not affect the affinity of GR for DNA binding elements,44 rather it stabilizes GR with heat shock protein,45 leading to a reduction of nuclear translocation.46,47 and would be consistent with partial ‘agonist’ activity demonstrated here. This provides an additional potential mode of action for antagonizing GR effects, which may be exploited in future drug development efforts.

Summary

A novel cell-based assay using a 1536-well plate format was developed to screen 9,920 compounds at seven to fifteen concentrations (PubChem AID: 451). All GR ligands were detected with EC50 values in the nM range. The use of freshly prepared cell suspensions shortened the assay cycle time and was a critical to the optimization in a1536-well format. Our retrospective analysis using false positive occurrence as an indicator showed that the assay had good accuracy. As well, the assay demonstrated acceptable sensitivity as judged by the identification of the relevant glucocorticoids in the collection. Alterations in GR translocation may be responsible for glucocorticoid resistance, suggesting additional mechanisms by which to modulate GR activtiy.20, 21 Thus, identifying non-steroidal small molecules which interfere with the GR translocation apparatus may have significant therapeutic value.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Molecular Libraries Initiative of the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research and the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- Dex

dexamethasone

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EFC

enzymatic fragment complementation

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- qHTS

quantitative high throughput screening

- S/B

signal-to-background ratio

- TP

true positive

- FP

false positive

- FN

false negative

- TN

true negative

Footnotes

In transient transfection experiments, GR Prolabel fusions from GR expression vectors with Prolabel at either the C- or N-terminus gave similar expression levels and stimulation with dexamethasone (K. Olson, unpublished result)

References

- 1.Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G. Steroid hormone receptors: many actors in search of a plot. Cell. 1995;83:851–857. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karin M. New twists in gene regulation by glucocorticoid receptor: is DNA binding dispensable? Cell. 1998;93:487–490. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adcock IM, Caramori G. Cross-talk between pro-inflammatory transcription factors and glucocorticoids. Immunol Cell Biol. 2001;79:376–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2001.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bia C, Schmidt A, Freedman Steroid Hormone Receptors and Drug Discovery: Therapeutic Opportunities and Assay Designs. Assay Drug Devel Technol. 2003;1:843–852. doi: 10.1089/154065803772613471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes PJ. Anti-inflammatory actions of glucocorticoids: molecular mechanisms. Clin Sci (Lond) 1998;94:557–572. doi: 10.1042/cs0940557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herr I, Pfitzenmaier J. Glucocorticoid use in prostate cancer and other solid tumours: implications for effectiveness of cytotoxic treatment and metastases. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:425–430. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70694-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pui CH, Evans WE. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:166–178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inglese J, et al. High-throughput screening assays for the identification of chemical probes. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:466. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Udenfriend S, Gerber LD, Brink L, Spector S. Scintillation proximity radioimmunoassay utilizing 125I-labeled ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:8672–8676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosworth N, Towers P. Scintillation proximity assay. Nature. 1989;341:167–168. doi: 10.1038/341167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin S, Bock CL, Gardner DB, Webster JC, Favata MF, Trzaskos JM, Oldenburg KR. A high-throughput fluorescent polarization assay for nuclear receptor binding utilizing crude receptor extract. Anal Biochem. 2002;300:15–21. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Necela BM, Cidlowski JA. Development of a flow cytometric assay to study glucocorticoid receptor-mediated gene activation in living cells. Steroids. 2003;68:341–350. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(03)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willemsen P, Scippo ML, Kausel G, Figueroa J, Maghuin-Rogister G, Martial JA, Muller M. Use of reporter cell lines for detection of endocrine-disrupter activity. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;378:655–663. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cadepond F, et al. Heat shock protein 90 as a critical factor in maintaining glucocorticosteroid receptor in a nonfunctional state. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5834–5841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richter K, Buchner J. Hsp90: chaperoning signal transduction. J Cell Physiol. 2001;188:281–290. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambert JR, Nordeen SK. Steroid-selective initiation of chromatin remodeling and transcriptional activation of the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter is controlled by the site of promoter integration. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32708–32714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito K, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM. Glucocorticoid receptor recruitment of histone deacetylase 2 inhibits interleukin-1beta-induced histone H4 acetylation on lysines 8 and 12. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6891–6903. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6891-6903.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovacs JJ, et al. HDAC6 regulates Hsp90 acetylation and chaperone-dependent activation of glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell. 2005;18:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito K, et al. Histone deacetylase 2-mediated deacetylation of the glucocorticoid receptor enables NF-kappaB suppression. J Exp Med. 2006;203:7–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews JG, Ito K, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM. Defective glucocorticoid receptor nuclear translocation and altered histone acetylation patterns in glucocorticoid-resistant patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1100–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inglese J, editor. Measuring Biological Responses with Automated Microscopy. Vol. 414. Elsevier Acadmeic Press; San Diego: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor DL, Haskins JR, Giuliano KA, editors. High Content Screening. Vol. 356. Humana Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auld DS, et al. Fluorescent protein-based cellular assays analyzed by laser-scanning microplate cytometry in 1536-well plate format. Methods Enzymol. 2006;414:566–589. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)14029-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baens M, Noels H, Broeckx V, Hagens S, Fevery S, Billiau AD, Vankelecom H, Marynen P. The dark side of EGFP: defective polyubiquitination. PLoS ONE. 2006;1(1):e54. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fung P, et al. A homogeneous cell-based assay to measure nuclear translocation using beta-galactosidase enzyme fragment complementation. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2006;4:263–272. doi: 10.1089/adt.2006.4.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wehrman TS, Casipit CL, Gewertz NM, Blau HM. Enzymatic detection of protein translocation. Nat Methods. 2005;2:521–527. doi: 10.1038/nmeth771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eglen RM. Enzyme fragment complementation: a flexible high throughput screening assay technology. Assay Drug Devel Technol. 2002;1:97–104. doi: 10.1089/154065802761001356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalderon D, Roberts BL, Richardson WD, Smith AE. A short amino acid sequence able to specify nuclear location. Cell. 1984;39:499–509. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saphire AC, Bark SJ, Gerace L. All four homochiral enantiomers of a nuclear localization sequence derived from c-Myc serve as functional import signals. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29764–29769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inglese J, et al. Quantitative high-throughput screening: A titration-based approach that efficiently identifies biological activities in large chemical libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11473–11478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niles WD, Coassin PJ. Piezo- and Solenoid Valve-Based Liquid Dispensing for Miniaturized Assays. Assay Drug Devel Technol. 2005;3:189–202. doi: 10.1089/adt.2005.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleveland PH, Koutz PJ. Nanoliter dispensing for uHTS using pin tools. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2005;3:213–225. doi: 10.1089/adt.2005.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peterson WW. The theory of signal dectectability. IRE Transactions on Information Theory. 1954;4:171–212. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swets JA. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. 1988;240:1285–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.3287615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gribbon P, et al. Evaluating real-life high-throughput screening data. J Biomol Screen. 2005;10:99–107. doi: 10.1177/1087057104271957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hammer S, Spika I, Sippl W, Jessen G, Kleuser B, Holtje HD, Schafer-Korting M. Glucocorticoid receptor interactions with glucocorticoids: evaluation by molecular modeling and functional analysis of glucocorticoid receptor mutants. Steroids. 2003;68:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(03)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin S, Bzock CL, Gardner DB, Webster JC, Favata MF, Trzaskos JM, Oldenburg KR. A high-throughput fluorescent polarization assay for nuclear receptor binding utilizing crude receptor extract. Analytical Biochem. 2002;300:15–21. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gagne D, Pons M, de Paulet C. Analysis of the relation between receptor binding affinity and antagonist efficacy of antiglucocorticoids. J Steroid Biochem. 1986;25:315–322. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(86)90242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis RE, et al. A Cell-Based Assay for IkappaBalpha Stabilization Using A Two-Color Dual Luciferase-Based Sensor. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2007;5:85–104. doi: 10.1089/adt.2006.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spitz IM, Bardin CW. Mifepristone (RU 486)--a modulator of progestin and glucocorticoid action. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:404–412. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308053290607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang S, Jonklaas J, Danielsen M. The glucocorticoid agonist activities of mifepristone (RU486) and progesterone are dependent on glucocorticoid receptor levels but not on EC50 values. Steroids. 2007;72(6–7):600–8. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pandit S, Geissler W, Harris G, Sitlani A. Allosteric effects of dexamethasone and RU486 on glucocorticoid receptor-DNA interactions. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1538–1548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Groyer A, Schweizer-Groyer G, Cadepond F, Mariller M, Baulieu EE. Antiglucocorticosteroid effects suggest why steroid hormone is required for receptors to bind DNA in vivo but not in vitro. Nature. 1987;327:624–626. doi: 10.1038/328624a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moguilewsky M, Philibert D. RU 38486: potent antiglucocorticoid activity correlated with strong binding to the cytosolic glucocorticoid receptor followed by an impaired activation. J Steroid Biochem. 1984;20:271–276. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(84)90216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Distelhorst CW, Howard KJ. Evidence from pulse-chase labeling studies that the antiglucocorticoid hormone RU486 stabilizes the nonactivated form of the glucocorticoid receptor in mouse lymphoma cells. J Steroid Biochem. 1990;36:25–31. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(90)90110-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]