Abstract

Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) family chaperone members can catalyze the thiol-disulfide exchange reaction with pairs of cysteines. There are 14 protein disulfide isomerase family members, but the ability to catalyze a thiol disulfide exchange reaction has not been demonstrated for all members. ERp18 shows partial oxidative activity as a PDI. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the participation of the endoplasmic reticulum protein chaperone thio-oxidoreductase in gonadotropin releasing hormone receptor expression at the plasma membrane. COS-7 cells were cultured, plated, and transfected with 25 ng (unless indicated) WT human GnRHR, or mutant GnRHR (Cys14Ala and Cys200Ala) and pcDNA3.1 without insert (empty vector) or ERp18 cDNA (75 ng/well), pre-loaded for 18 h with 1 μCi myo-[2-3H(N)]-inositol in 0.25 ml DMEM and treated for 2 h with Buserelin. We observed a decrease in maximal IP production in response to Buserelin in the cells co-transfected with hGnRHR, and from 20 ng to 75 ng of hERp18 compared with cells co-transfected with hGnRHR and empty vector. The decrease in maximal IP was proportional to the amount of ERp18 DNA over the range examined. Mutants (Cys14Ala and Cys200Ala) that could not form the Cys14– Cys200 bridge essential for plasma membrane routing of the hGnRHR, did not change the maximal IP production when they were co-transfected with hERp18. These results suggest that hERp18 has a reduction role on disulfide bond in wild type hGnRHR folding.

Keywords: protein chaperones, gonadotropin releasing hormone receptor, calnexin, calreticulin, ERp18

After synthesis in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are often folded and assembled to be packaged into the ER-derived COPII-coated vesicles and transported through the Golgi apparatus and the trans-Golgi network in order to arrive at the plasma membrane. During transportation through the ER and Golgi structures, GPCRs are submitted to post-translational modifications to acquire the mature conformation (1). These events —folding and trafficking of newly synthesized proteins— are highly regulated processes that likely comprise a number of different chaperone molecules belonging to the cell’s quality control system (QCS). These QCS chaperones recognize non-native conformations of newly synthesized proteins and prevent their aggregation and export of the incompletely folded chains from the ER (2). When the maturation of a newly synthesized protein is aborted or inefficiently performed, chaperones catalyze a covalent bond between ubiquitin and the unfolded protein. This reaction targets misfolded proteins to proteasomal degradation by the ER-associated degradation process (3–5). A wide number of diseases are associated with degradation of misfolded proteins such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, diabetes insipidus, and others (6). When the human gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (hGnRHR), the smallest representatives of this GPCR superfamily of receptors, is not expressed in the cell’s plasma membrane because it was retained in the ER or eventually degraded in the cytosol, its normal function (activation of luteinizing hormone release) is not performed and this results in the disease, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (1,7). Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism is characterized by 1) complete or partial absence of any endogenous GnRH-evoked LH pulsations, 2) delayed sexual development and, 3) normalization of pituitary and gonadal function in response to physiological regiments of exogenous GnRH replacement (8).

Chaperones are an interesting potential therapeutic target because of their role in the cellular QCS, regulating the folding and assembly of newly synthesized proteins, including hGnRHR (1). They are present in the ER, mitochondria and cytoplasm, and comprise a wide class of proteins that may be categorized into five groups: the heat shock protein family; lectins; substrate-specific; protein disulfide isomerases (PDI) and peptidyl prolyl isomerases (6). Each group of chaperones has a different chemical means to retain, refold and assemble misfolded proteins or promote their eventual degradation. One of these groups is the PDI family of chaperones. They recognize and catalyze the formation and isomerization of non-native disulfide bonds (9).

PDI family members can catalyze the thiol-disulfide exchange reaction with a pair of cysteines that are frequently arranged in a Cys-X-X-Cys motif (where X is any amino acid). There are 14 PDI family members, but the ability to catalyze a thiol disulfide exchange reaction has not been shown for all members. Some members like PDIr, ERp72, P5, PDIp, ERp28, and ERp18 have the same or partial oxidative activity as PDI, while only ERp57 has the ability to reduce disulfide-bonds (10, 11).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the participation of the endoplasmic reticulum protein chaperone thio-oxidoreductase in gonadotropin releasing hormone receptor expression at the plasma membrane.

Cos-7 cells were cultured, plated, and transfected, as previously reported (12), with 25 ng (unless indicated) WT human GnRHR, or mutant GnRHR (C14A and C200A) and pcDNA3.1 without insert (empty vector) or ERp18 cDNA (75 ng/well), as indicated, and 1 μl lipofectamine in 0.125 ml OPTI-MEM (room temperature), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Empty vector (pcDNA3.1, without insert) was included to bring the total cDNA to a final concentration of 100 ng/well which provides optimal transfection efficiency (12, 13). Five hours after transfection, 0.125 ml DMEM with 20% fetal bovine serum and 20 μg/ml gentamicin was added to the wells. Twenty three hours after transfection, cells were washed, then pre-loaded for 18 h with 1 μCi myo-[2-3H(N)]-inositol in 0.25 ml DMEM (prepared without inositol (12)). The cells were then washed twice with 0.25 ml DMEM containing 5 mM LiCl (without inositol), treated for 2 h with 0.25 ml of the indicated Buserelin concentration in the same medium (LiCl prevents inositol phosphate (IP) degradation). Total IPs were determined as described previously (12, 14). Data are averaged from at least three independent experiments (15).

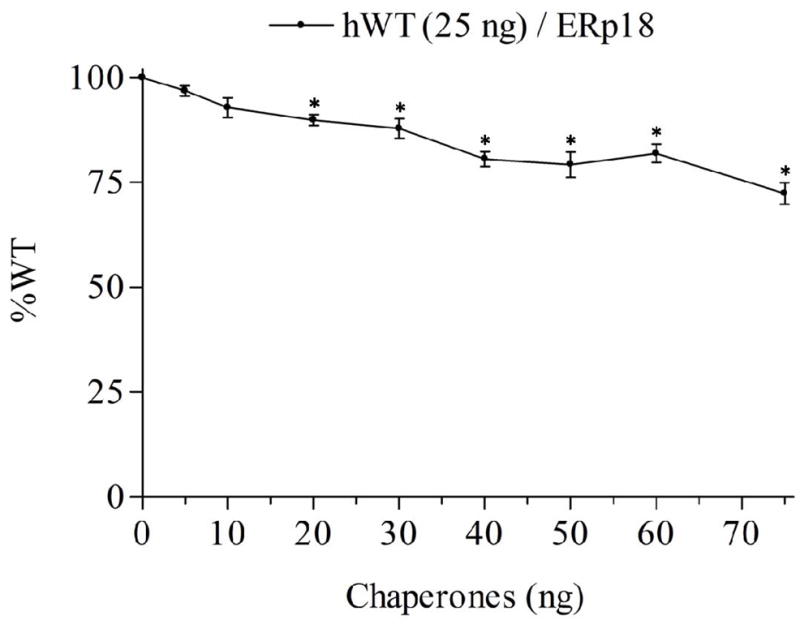

We observed a decrease in maximal IP production in response to Buserelin in the cells co-transfected with hGnRHR and from 20 ng to 75 ng of hERp18 compared with cells co-transfected with hGnRHR and empty vector (Figure 1). The decrease in maximal IP was proportional to the amount of ERp18 DNA over the range examined. These results suggest the participation of ERp18 in GnRHR folding and assembly.

Figure 1.

WT% indicate the IP production upon Buserelin stimulation of Human WT GnRHR co-transfected with hERp18 chaperone. Mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments in triplicate incubations. The asterisks indicate P<0.05 compared with WT hGnRHR (25 ng) without ERp18 co-transfected. The experiment was analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post test.

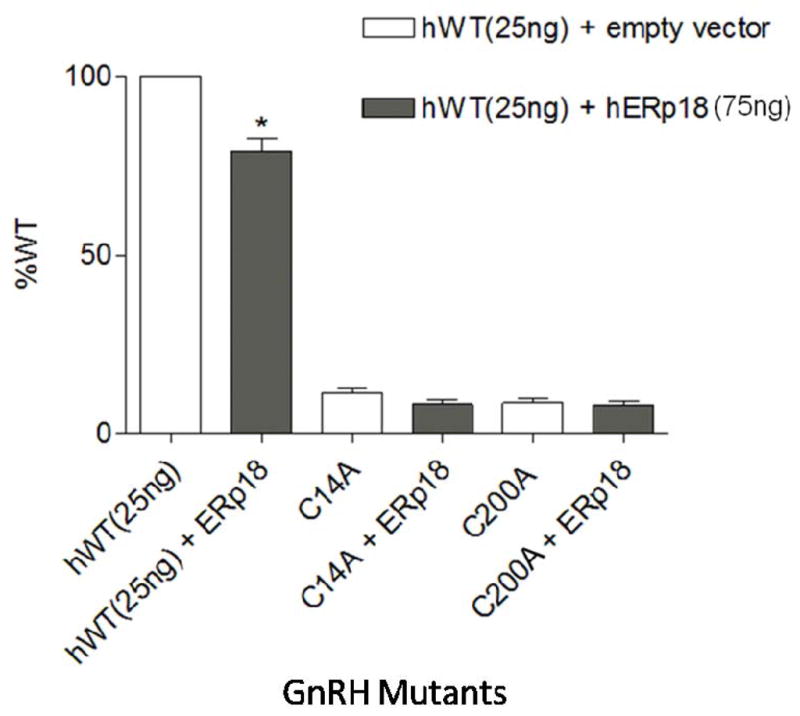

WT hGnRHR has two disulfide-bond bridges—Cys114–Cys196 and Cys14–Cys200. All mutants without the disulfide bridge (Cys114–Cys196) remain in the ER and can never be rescued by IN3 (a pharmacological chaperone with the ability to rescue unfolded proteins by correcting their routing, 7, 16, 17)). However, the Cys14–Cys200 bridge can be rescued by IN3 (17). In our experiments, mutants that could not form the Cys14– Cys200 bridge (i.e., Cys14Ala and Cys200Ala) did not change the maximal IP production when they were co-transfected with hERp18 (Figure 2), but when this bridge was present (WT hGnRHR), the co-transfection with hERp18 decreased maximal IP production. These results suggest that hERp18 has a reduction role on disulfide bond in wild type hGnRHR folding. Conversely, in vitro studies (18) have demonstrated that reduced form of ERp18 is more stable than oxidized form, suggesting that it is involved in disulfide bond formation. Moreover, they also have demonstrated that ERp18 is relatively inefficient at catalyzing oxidoreductase reactions (15% of a domain of PDI, 18), which is probably because it lacks the glutamic-acid proton acceptor (11). However, inside the ER there are many different oxidoreductases with a range of abilities to catalyze oxidoreductase reactions. Then, even with a relatively inefficient power to catalyzing a oxidoreductase reaction there are many possibilities of interaction between ERp18 and others oxidoreductase proteins to reduce the disulfide bond in wild type hGnRHR.

Figure 2.

WT% indicate the IP production upon Buserelin stimulation of Human WT and mutants GnRHR co-transfected with hERp18 chaperone. Mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments in triplicate incubations. The asterisks indicate P<0.05 compared with WT hGnRHR (25 ng) without ERp18 co-transfected. The experiment was analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post test.

Acknowledgments

The work described was supported by NIH grants HD-19899, RR-00163, HD-18185, and TW/HD-00668.

Reference List

- 1.Conn PM, Ulloa-Aguirre A, Ito J, Janovick JA. G protein-coupled receptor trafficking in health and disease: lessons learned to prepare for therapeutic mutant rescue in vivo. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:225–250. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.3.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellgaard L, Helenius A. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:181–191. doi: 10.1038/nrm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodsky JL. The protective and destructive roles played by molecular chaperones during ERAD (endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation) Biochem J. 2007;404:353–363. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meusser B, Hirsch C, Jarosch E, Sommer T. ERAD: the long road to destruction. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:766–772. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong C, Filipeanu CM, Duvernay MT, Wu G. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor export trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:853–870. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ni M, Lee AS. ER chaperones in mammalian development and human diseases. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3641–3651. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janovick JA, Brothers SP, Cornea A, Bush E, Goulet MT, Ashton WT, et al. Refolding of misfolded mutant GPCR: post-translational pharmacoperone action in vitro. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;272:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seminara SB, Hayes FJ, Crowley WF., Jr Gonadotropin-releasing hormone deficiency in the human (idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and Kallmann’s syndrome): pathophysiological and genetic considerations. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:521–539. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.5.0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jessop CE, Chakravarthi S, Watkins RH, Bulleid NJ. Oxidative protein folding in the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:655–658. doi: 10.1042/BST0320655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwaller M, Wilkinson B, Gilbert HF. Reduction-reoxidation cycles contribute to catalysis of isomerization by protein-isomerase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7154–7159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellgaard L, Ruddock LW. The human protein disulfide isomerase family: substrate interactions and functional properties. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:28–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brothers SP, Cornea A, Janovick JA, Conn PM. Human loss-of-function gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor mutants retain wild-type receptors in the endoplasmic reticulum: molecular basis of the dominant-negative effect. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1787–1797. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janovick JA, Ulloa-Aguirre A, Conn PM. Evolved regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor cell surface expression. Endocrine. 2003;22:317–327. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:22:3:317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huckle WR, Conn PM. The relationship between gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated luteinizing hormone release and inositol phosphate production: studies with calcium antagonists and protein kinase C activators. Endocrinology. 1987;120:160–169. doi: 10.1210/endo-120-1-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu BT. The competitive and noncompetitive antagonism of receptor-mediated drug actions in the presence of spare receptors. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1993;29:85–91. doi: 10.1016/1056-8719(93)90055-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulloa-Aguirre A, Janovick JA, Leanos-Miranda A, Conn PM. Misrouted cell surface GnRH receptors as a disease aetiology for congenital isolated hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10:177–192. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janovick JA, Knollman PE, Brothers SP, Ayala-Yanez R, Aziz AS, Conn PM. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor trafficking by inefficient plasma membrane expression: molecular basis of an evolved strategy. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8417–8425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alanen HI, Williamson RA, Howard MJ, Lappi AK, Jantti HP, Rautio SM, et al. Functional characterization of ERp18, a new endoplasmic reticulum-located thioredoxin superfamily member. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28912–28920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304598200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]