Abstract

Solicitous parental responses to stomach aches may perpetuate chronic abdominal pain in children. Discussing these issues in clinical practice is difficult as parents feel misunderstood and blamed for their child’s pain. Focusing on parental worries and beliefs that motivate solicitous responses may be better accepted.

Objectives

Our aim was to determine parental fears, worries and beliefs about their child’s chronic abdominal pain that influence parental responses to child’s pain.

Methods

In two studies, a large online sample and a smaller community sample consisting of parents with children who suffer from abdominal pain, we developed and evaluated a self-report questionnaire to assess parental Worries and Beliefs about Abdominal Pain (WAP).

Results

Principal component analysis identified four subscales: (1) Pain-is-Real; (2) Desire for Care; (3) Worry about Coping; and (4) Exacerbating Factors. The WAP is easily understood and possesses adequate initial reliability (Cronbach alphas of .7–.9) and shows good initial validity (i.e., families who consulted a physician for their child’s pain scored higher on the WAP than families who did not consult a physician and the WAP correlates with parental reactions to the child’s pain).

Conclusions

Discussing parents’ fears and worries about their children’s chronic abdominal pain may facilitate discussions of social learning of gastrointestinal illness behavior.

Introduction

Abdominal pain without a clear organic cause that occurs regularly over a period of several months and is severe enough to interfere with activities is a common pediatric problem. It is commonly referred to as Functional Abdominal Pain (FAP). The prevalence estimates for FAP range from 0.3 to 19% in Western countries (1), making it one of the most common chronic pain disorders of childhood. Chronic abdominal pain is associated with increased psychological distress and disruption of daily activities including school attendance (2). Many children continue to experience symptoms even in adulthood (3;4).

When a child is sick or in pain, parents must interpret the seriousness of the symptoms and decide how to respond. Parental actions or reactions may teach children how to approach future illness and health. According to social learning theory, parental modeling and reinforcement of the sick role increases the likelihood of pediatric functional GI symptoms that may persist into adulthood (5;6). Two types of learning can be distinguished. First, parents may model sick role behavior: by observing a parent who suffers from chronic abdominal pain, children learn how to interpret and cope with their own GI symptoms. Prospective studies have shown that children of parents who suffer from Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) –which main characteristic is chronic abdominal pain- report more GI symptoms, miss more days out of school and have more doctor’s visits than children whose parents do not suffer from IBS (7). Second, parents can inadvertently reinforce illness behaviors in their children when attempting to be protective and nurturing. People with IBS recall receiving gifts or being excused from normal activities when suffering from minor illnesses in childhood more than other individuals (6;8). These data suggest that somatic symptoms may be learned or maintained because of the consequences associated with them. In a study among 151 pediatric FAP patients, positive attention and activity restriction predicted symptom maintenance 2 weeks later (9). Parents are the most likely adults to give positive attention to a sick child and to excuse him/her from activities like going to school.

Discussing social learning issues in clinical practice is extremely difficult. Parents may want clinicians to identify a medical cause of their child’s abdominal pain. By focusing on parental reactions to their child’s abdominal pain rather than an underlying pathology, clinicians may give the impression that they are blaming the parent for their child’s illness. In addition, many parents believe that showing sympathy is an important part of nurturing and they may become angry at the clinician for disregarding the child’s needs.

Addressing the cognitions that drive social learning may be more acceptable to parents. Examining and discussing the parents’ own fears and worries is likely to be perceived as less judgmental than recommending behavioral changes. In a previous study (10) we determined the most common parental cognitions about their children’s abdominal pain. Parents worried about the effects of pain on their children; believed their children did not complain easily of pain; felt helpless to know how to deal with their children’s suffering; desired care and treatment by physicians, and acknowledged that genetics, stress and disease were all factors contributing to the pain. Another qualitative study exploring how mothers of children with chronic abdominal pain view seeking medical help, identified similar worries such as a desire for diagnosis/care, frustration in dealing with doctors, and feeling inadequate as a parent (11). These fears and worries may explain why parents reinforce illness behavior.

Assessing the specific nature of parental cognitions that affect their children’s’ illness behavior may open the doors to more effective interventions to reduce morbidity, disability, and healthcare costs and utilization. A comprehensive questionnaire is therefore a desirable aid for this purpose. The aim of the present studies was to develop and initially evaluate a questionnaire to identify the fears and beliefs of parents that may motivate parental responses to pain. When fully developed the questionnaire may be used as a clinical instrument to identify and guide targeted intervention for families where worries and beliefs play a significant role in illness or healthcare-seeking, and for identifying families at heightened risk for chronic GI problems.

Material and Methods Study 1

Development of the Parental Worries and Beliefs about Abdominal Pain questionnaire

Questionnaire development

The aim of the first study was the development and initial evaluation of a questionnaire to measure the main domains or themes of common parental worries and beliefs about abdominal pain in their children. In order to develop the questionnaire more than 100 questionnaire items were drawn from interview transcripts of a previous qualitative study (10). All items were examined by a team of internal reviewers (study authors MvT, OP, and WW) familiar with questionnaire development. Items that were similar in content or confusing were deleted. Items that dealt with behaviors rather than cognitions were deleted. Negative items (e.g. “I do not feel my child’s stomachaches are normal”) were rephrased. Items that dealt with two issues (e.g. “I feel my child fakes or uses her stomach aches to get attention”), were rewritten into two separate statements. This resulted in 51 items available for further testing (see Table 1). All items were given a 5-point rating scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Table 1.

The Rotated Component Solution

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I believe my child exaggerates or fakes stomach aches. | −.65 | .0 | .25 | .0 |

| 2. | I feel that my child uses his/her stomach aches to get attention or get out of things | −.64 | .0 | .30 | .0 |

| 3. | In order for my child to complain of stomach aches, (s)he must be in a lot of pain | .58 | .0 | .0 | .0 |

| 4. | I believe a child can only be in this much pain if something is really wrong | .54 | .26 | .27 | .0 |

| 5. | I feel that nobody should be in as much pain as my child is. | .52 | .27 | .28 | .0 |

| 6. | I want doctors to prescribe medications for my child’s stomach aches | .49 | .26 | .21 | .0 |

| 7. | It is okay to ignore my child’s stomachaches | −.47 | .0 | .0 | .0 |

| 8. | I feel confident that my child will outgrow his/her stomachaches | −.46 | .0 | .0 | .0 |

| 9. | It is okay to dismiss my child’s stomachaches | −.43 | .0 | .0 | .0 |

| 10. | I believe my child’s stomachaches are normal | −.41 | −.21 | .0 | .0 |

| 11. | I am frustrated with my doctor for failing to treat my child’s stomach aches. | .0 | .85 | .0 | .0 |

| 12. | I am frustrated with my child’s doctors for failing to tell me what is wrong with my child | .0 | .81 | .0 | .0 |

| 13. | I feel that doctors could do more to eliminate my child’s stomach aches. | .0 | .82 | .0 | .0 |

| 14. | I worry that my doctor doesn’t understand my child’s stomach aches. | .0 | .78 | .0 | .0 |

| 15. | I feel frustrated with my child’s doctors for suggesting that my child is faking the stomach aches | .0 | .60 | .0 | .0 |

| 16. | I believe doctors should identify what is wrong with my child | .34 | .54 | .0 | .0 |

| 17. | It is alright to keep seeing other physicians until we figure out what is wrong with my child. | .0 | .52 | .0 | .0 |

| 18. | I worry that giving my child pain medications does nothing to treat the underlying problem. | .0 | .43 | .21 | .0 |

| 19. | I worry about what to do when my child has stomach aches. | .22 | .0 | .63 | .0 |

| 20. | I feel frustrated for failing to help my child when (s)he has stomachaches | .21 | .21 | .63 | .0 |

| 21. | I have a hard time deciding when to give my child medications for his/her stomachaches | .0 | .0 | .60 | .0 |

| 22. | I feel guilty for thing my child is exaggerating or faking his/her stomachaches | −.25 | .0 | .53 | .0 |

| 23. | When I can’t help my child I feel inadequate as a parent | .0 | .26 | .52 | .0 |

| 24. | I have a hard time deciding when to take my child to a doctor because of his/her stomachaches | .0 | .0 | .51 | .0 |

| 25. | I’m afraid to ignore things that should be checked by a doctor | .0 | .0 | .50 | .0 |

| 26. | I worry about not being able to reduce my child’s stomach aches | .21 | .0 | .46 | .0 |

| 27. | My child’s stomachaches are worse when (s)he is under stress at school | −.22 | .0 | .20 | .66 |

| 28. | My child’s stomachaches are worse when (s)he is under stress at home | −.28 | .0 | .21 | .60 |

| 29. | I have wondered if stomachaches can run in families | 0 | .0 | .0 | .53 |

| 30. | My child’s stomachaches are similar to somebody in my family have had at one point | 0 | .0 | .0 | .50 |

| 31. | I worry about my child’s stomach aches affecting his/her school performance. | .28 | 0 | .24 | .49 |

| 32. | I should be able to make my child’s stomach aches go away | .0 | .26 | .31 | .0 |

| 33. | I worry that my child will have stomach aches for the rest of his/her life. | .41 | 0 | 0 | .50 |

| 34. | I worry about my child missing out on things because of his/her stomach aches | .34 | .0 | .31 | .49 |

| 35. | I worry that my child’s stomach aches, even when minor, will inevitably get worse. | .48 | .0 | .28 | .25 |

| 36. | I feel my child’s stomach aches are predictable | −.33 | .0 | .0 | .0 |

| 37. | My child complains about stomach aches easily | −.32 | .0 | .43 | .0 |

| 38. | My child has stomach aches more often than (s)he tells me | .33 | .0 | .0 | .25 |

| 39. | I would like doctors to suggest a treatment | .32 | .47 | .25 | .0 |

| 40. | I believe doctors can be helpful in telling me what to do when my child has a stomach aches | .0 | .0 | .22 | −.26 |

| 41. | I wish my child’s doctors would prescribe medications that help my child. | .45 | .39 | .29 | .0 |

| 42. | I have a hard time deciding when to take my child out of school because of his/her stomachaches | .0 | .0 | .43 | .46 |

| 43. | I feel that most things I can do for my child’s stomachaches are only temporary | .0 | .33 | .40 | .0 |

| 44. | I struggle between showing sympathy and ignoring my child’s stomachaches | −.51 | .0 | .44 | .0 |

| 45. | I feel that stress is causing my child’s stomachaches | −.36 | .0 | .21 | .53 |

| 46. | I believe that a lack of exercise might be related to my child’s stomachaches | .0 | .0 | .0 | .32 |

| 47. | I am worried that the foods my child eats cause his/her stomachaches | .0 | .0 | .0 | .24 |

| 48. | I fear that my child has a serious or life− threatening illness | .39 | .0 | .24 | .0 |

| 49. | I’d worry something is wrong even if a doctor couldn’t find anything | .33 | .29 | .33 | .0 |

| 50. | I believe others understand my child’s stomach aches. | .0 | .0 | .0 | .0 |

| 51. | I’m worried about my child’s weight | .0 | .0 | .0 | .0 |

Protocol

Parents of children who suffer from chronic abdominal pain were recruited through the website of the Center for Functional GI and motility disorders and postings on news boards of several websites dealing with IBS, functional GI disorders or parenting issues. The questionnaire was administered online, along with additional questions on gender of child and parent, age of the child, duration and frequency of abdominal pain, the parent’s own chronic abdominal pain, physician consultation for abdominal pain, and questions asking respondents to rate the understandability of the questionnaire. Data were collected at a secure website. Parents who had multiple children with chronic abdominal pain were requested to complete the items about only one of their children. No monetary rewards were provided for participating in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Biomedical Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Analyses

Principal Component analysis was used to reduce the number of items and determine the existence of subscales within the original test questionnaire. Internal consistency of the newly designed subscales was determined by Cronbach’s alphas. T-tests comparing Consulting vs non-Consulting families were performed to test the initial validity of the questionnaire’s scales. All analyses were performed with SPSS 13.0.

Results of study 1

Subjects

A total of 537 parents, mostly mothers (94.8%) completed the questionnaire, and 23.7% of the parents reported that they suffer from chronic abdominal pain themselves. The mean age of the children was 8.3 (SD=2.9) years and 66.3% were girls. All children suffered from abdominal pain with half of the children (50.5%) complaining of pain most days or every day.

Reduction of items

All items were well understood. On a 5-point understandability scale (where 5 meant “completely understandable”), administered with the WAP questionnaire, the mean ratings for the individual questions ranged from 4.29 to 4.92. Although some items were somewhat positively or negatively skewed, all items had minimum and maximum of 1 and 5. There was no kurtosis (i.e. abnormal peakness of the normal distribution). Thus, there was no basis for deleting items due to the lack of understandability or violation of normal distribution.

To reduce the number of items and determine the existence of subscales in the WAP, Principal Component Analysis was used. Nine multivariate outliers were removed based on Mahalanobis distance at p < .001 leaving a sample of N=528. An initial PCA yielded 15 factors with Eigenvalues >1. A scree plot revealed a break around the 3rd to 5th factors. PCA with varimax rotation with 3, 4 and 5 factors were performed. Rotation after extraction is performed to maximize high correlation between factors and variables and minimize low ones. Examination of the factor solutions revealed the best interpretability with 4 factors, explaining 36.0% of the variance. When oblique rotation was requested (quartimin) correlations were found between the first and both second (−.30) and fourth factor (−.29). However, because the correlation was modest and the remaining correlations were low, orthogonal rotation was chosen.

Table 1 shows the rotated factor loadings. All loadings <.20 are depicted as zero. Items with factor loadings > 0.40 and at least 0.20 difference between factor loadings on two factors were retained. With this cut-off, 31 of the 51 items were retained. The factors were labeled and conceptualized as follows:

Pain-is-Real; focuses on the meaning of symptoms. Because of the negative factor loadings of many items parents indicated that symptoms were real and not used for attention seeking (10 items).

Desire for Care; deals with a need for diagnosis or care and frustration with physician care (8 items).

Worry about Coping; expresses coping difficulties with the child’s abdominal pain (8 items).

Exacerbating Factors; recognizes the role of stress and heredity (5 items).

Reliability

Calculation of Cronbach’s α, to assess internal consistency for the 4 subscales yielded .77 for Pain-is-Real, .86 for Desire for Care, .75 for Worry about Coping and .74 for Exacerbating Factors. Deletion of items would not increase α significantly for any of the subscales.

As can be seen in Table 2 the inter-correlations between the scales were low for most scales. Desire for Care showed moderately strong correlations with Pain-is-Real and Worry about Coping.

Table 2.

Correlations among subscales

| Pain is Real | Desire for Care | Worry about Coping | Exacerbating Factors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain is Real | .40** | .10* | −.00 | |

| Desire for Care | .40** | .17** | ||

| Worry about Coping | .24** |

p <.05

p < .001

Validity

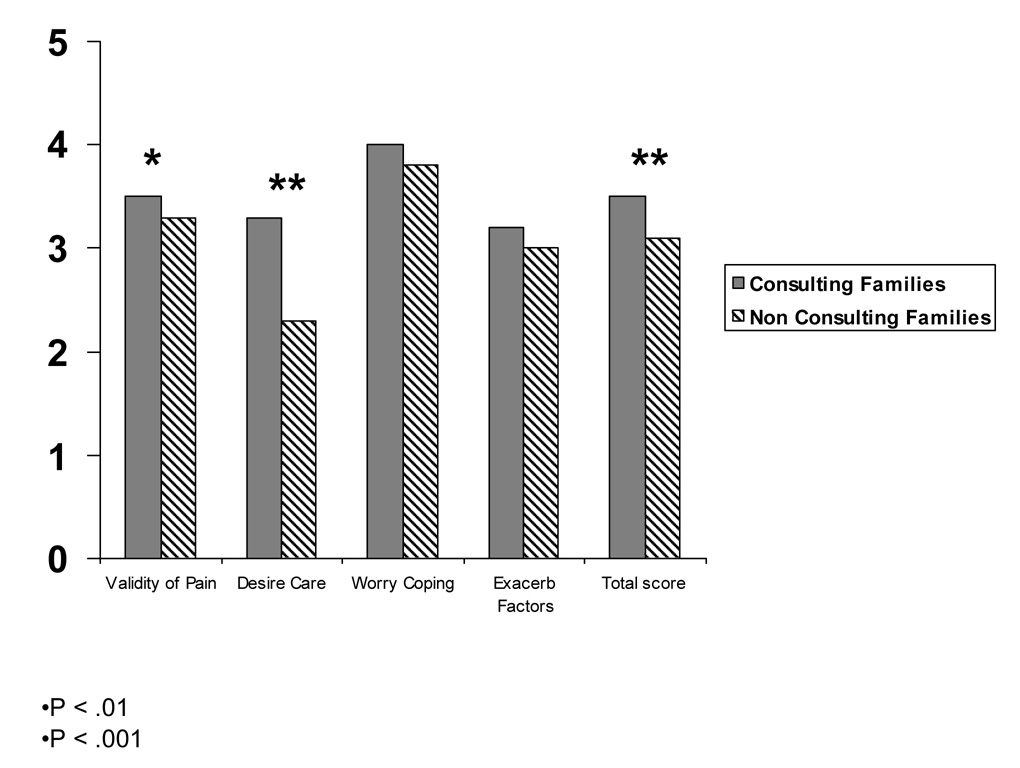

Arithmetic means for all the four subscales were computed and compared between families who did not consult a doctor (N=147; 27.4%) and families who visited a physician for their child’s abdominal pain (N=390, 72.6%). As can be seen from Figure 1, scores on the Pain-is-Real and Desire for Care scales were elevated in the Consulting Families.

Figure 1.

Mean Parental Worries and Beliefs of Abdominal Pain Subscale Scores for Consulting vs Non-Consulting Families.

Materials and Methods of study 2

Study Materials

The aim of the second study was to extend the validation of the WAP in a community sample and study the association of cognitions (as measured by the WAP) and parental response to the child’s pain. In order to do so all participants were asked to complete the 31 item WAP as developed in Study 1 and the Adult Responses to Child Symptoms Questionnaire (ARCS). The ARCS (9;12) is a validated 29 item questionnaire that assesses whether parents encourage, discourage or ignore a child’s illness behavior. Where the WAP measures cognitions, the ARCS measures behaviors. The ARCS consist of 3 subscales: (1) Protect, which is characterized by placing the child in a passive sick role, (2) Encourage and Monitor, which included engaging the child in activities while monitoring symptoms; and (3) Minimize, characterized by being critical of the child’s pain behaviors.

Subjects

Subjects were part of a larger study on the determinants of consulting behavior in children with recurrent abdominal pain, and a detailed description of the sampling method can be found elsewhere (13). In summary, subjects were recruited by contacting all fourth grade children from three school districts in North Carolina to identify children with chronic abdominal pain (N=5595). 566 Screening surveys were returned (10.1% response rate) and 115 children were considered to suffer from FAP on the basis of the following criteria: (1) no chronic medical conditions/impairment restricting daily activities; (2) 3 days or more of abdominal pain in the past 3 months, with at least 1 day where daily activity is restricted; and (3) lack of organic etiology for abdominal pain.

All families fulfilling the above criteria were contacted, and enrollment criteria were verified by telephone interview. We enrolled 85% of the contacted group (N=81), 40 of which had previously consulted a physician because of FAP (FAP-C), and 41 of which had not (FAP-NC). Half the sample were girls with a mean age of 10, and mostly Caucasian (77.8%). One parent was unemployed in 34.6% of the families and poor finances were reported by 14.8%. The study protocol was approved by the Biomedical Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Results of study 2

Cronbach’s α was .88 for Desire for Care, .86 for Worry about Coping, .67 for Pain-is-Real and .68 for Exacerbating Factors.

Consulting families scored higher on Desire for Care (M=2.6 vs. 1.7; p <.001) and Pain-is-Real (M=3.6 vs 3.2; p < .01) compared to non-consulting families. No significant differences were found for Worry about Coping and Exacerbating Factors. This is similar to previous findings in the online sample.

Pearson correlations were run between subscales of the WAP and the ARCS. Protect on the ARCS did not correlate significantly with any of the WAP scales. Minimizing Responses to child GI symptoms correlated positively with Pain-is-Real (r=.29; p ≤ .01). Encouraging and Distracting correlated positively with Pain-is-Real (r=.40; p ≤ .001), Desire for Care (r=.30; p ≤ .01) and Worry about Coping (r=.29, p ≤ .01).

Discussion

Psychometric properties

The Worries and Beliefs about Abdominal Pain questionnaire (WAP) is a multi dimensional 31 item questionnaire that assesses the most common parental worries about their children’s chronic abdominal pain. It consists of four subscales: Pain-is-Real, Desire for Care, Worry about Coping and Exacerbating Factors. The internal consistency of the WAP was reasonable to good both in the online and community samples. Initial support for concurrent validity was shown by the questionnaire’s ability to distinguish consulting families from non-consulting families. Parental worries were further associated with parental responses to children’s pain as measured by the ARCS showing initial construct validity.

There are several limitations to our studies. The online sample, while large, was self-selected and no information was available as to the causes of the chronic abdominal pain. The community sample, in contrast, was small had a low rate of participation and was limited to a very restricted age group. Nevertheless, the results in both samples were identical, which lends support to the generalizability of this questionnaire’s psychometric performance. In addition, our samples consisted mainly of mothers, and data on paternal worries are needed as they may have worries and beliefs that are not adequately captured by the WAP. In conclusion, initial evaluation of the WAP shows adequate reliability and validity but more studies are needed to further develop this questionnaire. For example, future studies need to assess test-retest reliability and determine the associations of the WAP to frequency of medical consultation, treatment outcomes, functional disability and quality of life.

Fear of an underlying disease did not appear to be a separate factor in this study. This is contrary to previous literature and clinical observation (10);(14), possibly reducing face validity of the scale. However, it is not known whether disease conviction is associated with reinforcement of illness behaviors. In a previous study we found that fear of an overlooked serious disease was not associated with medical consultation seeking (15). In this study parents who consulted a doctor for their child’s stomachache did not worry more about a serious illness in their children than parents who do not consult a doctor for their child’s symptoms. Similarly in a study by Claar and Walker (14) parents of children with and without an organic etiology of abdominal pain endorsed stress as a primary cause of their child’s symptoms and not physical factors showing that psychosocial influences on pain are well recognized by parents. These observations lend support for not finding a separate subscale for fear of a disease.

Despite these limitations and the need for further validation the WAP appears to be an instrument that can be important in research and clinical practice. Since the subscales do not have equal numbers of items, we recommend using the means of responses (note that items with negative factor loadings need to be reversed) on each subscale instead of sum scores to assess the relative prominence of different types of worries for individual parents. This could for example, help the clinician to know which worries are most important to address in each case (i.e., the subscale with the highest mean score). Sum scores would not be meaningful in this regard without normative data to identify abnormally low or high scores.

Clinical Relevance

The four subscales that emerged in the development of the WAP each provide potentially clinically useful insights into separate facets of parental cognitions when faced with their children’s pain. Pain-is-Real represents the struggle between showing sympathy and ignoring the pain. It includes worries about the intensity of the pain, beliefs about secondary gain from pain such as attention, and being comfortable with dismissing the pain. In a study by Walker and colleagues (5) parents acknowledge that ignoring the pain and distracting a child is helpful in reducing child pain complaints, and children also reported that their parent made them feel better. However, parents rated distraction as having greater potential negative long term impact on the child than attention. Many parents feel that showing sympathy and empathy is important and nurturing to their child. A strategy for the clinician is to first reassure the family that nothing major is wrong with their child and to explain what a functional disorder is. Parents need to be aware that the pain does not signal disease but is real and in itself disabling to their child. Secondly, a clinician needs to acknowledge the nurturing quality of showing empathy and sympathy, but to counsel parents on the benefits of acknowledge and distract. This means the parent can still acknowledge the child’s pain –without apologizing for it (e.g., “I’m really sorry you feel so bad”)- and then move on directly to distracting the child by talking about something unrelated to the pain such as an upcoming fun event, what to make for evening dinner or which gift to buy for someone’s birthday. It is important to emphasize that distraction does not mean disregarding a child’s needs or minimizing their symptoms; it is a way of helping a child to cope with their pain. Parents need to be made aware that children often prefer distraction as it makes them feel better and gives them more control over the pain (5).

Worry about coping deals with the inability of parents to know how to cope with their child’s symptoms. Parents often feel inadequate and frustrated because they are unable to help their child with his/her pain problem. They may also doubt their own decisions as to when to take a child to a doctor, when to ignore pain, and when to give medications. Clinicians can help families regain some control over the pain by identifying helpful medications, teaching coping strategies such as distraction, and providing clear strategies as to when to keep the child out of school, when to use medications and when to contact a physician immediately or for a regular appointment. Information on alarm symptoms as describe in Rome III (16) can be very useful to ease a worried parent’s mind. Sometimes children may have coping strategies that parents dismiss as not useful or inadequate (10). It is important to ask a child about what they do to help their pain and validate any potential helpful and not harmful coping strategies that children identify.

The Desire for Care scale assesses thoughts about doctors. It focuses on the need for diagnosis, treatment and care by physicians as well as tapping into frustrations about not receiving the desired or appropriate medical care. This scale represents parental expectations that the physician can find a cause (whether physiological or psychosocial) and cure the pain. These expectations lead to dissatisfaction with medical care since the treatment goals are unachievable and physicians are unable to assume all responsibility for the patient’s wellbeing. It is important for the physician to give patients control over the pain (see discussion above), make them responsible for their care and establish clear expectations of the treatment goals and shared responsibility. The focus should be on symptom management rather than a cure. Physicians should communicate clearly their continued availability to the parents and their intent to work with the family through this long and sometimes frustrating process of finding out what works best for this particular child.

Exacerbating Factors included the effects of stress on abdominal pain and familial tendencies for having abdominal pain. Familial tendencies are most often not centered on severe disease such as colon cancer in the family –although this is a possibility and needs to be addressed- but rather seem to focus on a parent, aunt or uncle who also suffers from a ‘nervous stomach’ (10). Most parents acknowledge that both physical and psychosocial factors play a role in their child’s and other family members pain (14). These parents are open to psychosocial interventions for the child’s pain, such as stress reduction or relaxation exercises, and want their child’s physician to discuss both physical and psychological etiological factors and treatment options. In families where the parents do not readily acknowledge a role of stress the clinician needs to keep an open mind that this may be true. Parents may also dismiss the role of stress since they worry the physician doesn’t take the pain seriously or will dismiss the patient when parents acknowledge a role of stress. Alternatively, parents may not realize the role of stress in disease. It is important to resist giving insight to parents and limit the discussion of psychosocial issues to what they can accept. If a parent is unsure about the role of stress it may be helpful for the child to keep a 2 week diary of pain levels, medications, stress and significant events (such as school tests, recitals, championship games etc.) to determine if stress and pain coincide.

In sum, when children present with chronic unexplained abdominal pain, parents will be looking to the clinician for help. Most parents will be open to discussing both medical and behavioral approaches to their child’s pain. Discussing parent’s own role in their child’s pain may be difficult. However it is important when working with families to realize that the parents are struggling to cope as well. Acknowledging their worries, beliefs and fears opens the discussion to changing parental behavior from solicitousness towards child’s symptoms to more beneficial coping strategies such as distraction and relaxation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by RO1 DK31369 and RO1 HD36069 and R24 67674.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Chitkara DK, Rawat DJ, Talley NJ. The epidemiology of childhood recurrent abdominal pain in Western countries: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(8):1868–1875. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scharff L. Recurrent abdominal pain in children: a review of psychological factors and treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 1997;17(2):145–166. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(96)00001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stickler GB, Murphy DB. Recurrent abdominal pain. Am J Dis Child. 1979;133(5):486–489. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1979.02130050030006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campo JV, Di Lorenzo C, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Colborn K, Gartner JC, et al. Adult outcomes of pediatric Recurrrent Abdominal Pain: Do they just grow out of it? Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):1–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker LS, Williams SE, Smith CA, Garber J, Van Slyke DA, Lipani TA. Parent attention versus distraction: impact on symptom complaints by children with and without chronic functional abdominal pain. Pain. 2006;122(1–2):43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitehead WE, Winget C, Fedoravicius AS, Wooley S, Blackwell B. Learned illness behavior in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27(3):202–208. doi: 10.1007/BF01296915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Walker LS, Von Korff M, Feld AD, Garner M, et al. Increased somatic complaints and health-care utilization in children: effects of parent IBS status and parent response to gastrointestinal symptoms. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;99(12):2442–2451. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Heller BR, Robinson JC, Schuster MM, Horn S. Modeling and Reinforcement of the Sick Role During Childhood Predicts Adult Illness Behavior. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1994;56(6):541–550. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199411000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker LS, Zeman JL. Parental response to child illness behavior. J Pediatr Psychol. 1992;17(1):49–71. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/17.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Tilburg MA, Venepalli N, Ulshen M, Freeman KL, Levy R, Whitehead WE. Parents' worries about recurrent abdominal pain in children. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2006;29(1):50–55. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200601000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smart S, Cottrell D. Going to the doctors: the views of mothers of children with recurrent abdominal pain. Child Care Health Dev. 2005;31(3):265–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2005.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Slyke DA, Walker LS. Mothers' responses to children's pain. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(4):387–391. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000205257.80044.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venepalli NK, van Tilburg MA, Whitehead WE. Recurrent abdominal pain: what determines medical consulting behavior? Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51(1):192–201. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Claar RL, Walker LS. Maternal attributions for the causes and remedies of their children's abdominal pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 1999;24(4):345–354. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/24.4.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Tilburg MAL, Palsson OS, Chitkara DK, Whitehead WE. Medical consultation for children's chronic stomachaches is related to a belief that the symptoms have a physical cause but is not related to anxiety about serious missed diagnosis. Gastroenterol. 2006;130(4):A501. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 3rd ed. Degnon Associates; 2006. [Google Scholar]